Abstract

Aims:

Even with the use of nerve-sparing techniques, there is a risk of bladder and sexual dysfunction after total mesorectal excision (TME). Laparoscopic TME is believed to improve this autonomic nerve dysfunction, but this is not demonstrated conclusively in the literature. In Indian patients generally, the stage at which the patients present is late and presumably the risk of autonomic nerve injury is more; however, there is no published data in this respect.

Materials and Methods:

This prospective study in male patients who underwent laparoscopic TME evaluated the bladder and sexual dysfunction using objective standardised scores, measuring residual urine and post-voided volume. The International Prostatic Symptom Score (IPSS) and International Index of Erectile Function score were used respectively to assess the bladder and sexual dysfunction preoperatively at 1, 3, 6 months and at 1 year.

Results:

Mean age of the study group was 58 years. After laparoscopic TME in male patients, the moderate to severe bladder dysfunction (IPSS <8) is observed in 20.4% of patients at 3 months, and at mean follow-up of 9.2 months, it was seen only in 2.9%. There is more bladder and sexual dysfunction in low rectal tumours compared to mid-rectal tumours. At 3 months, 75% had sexual dysfunction, 55% at median follow-up of the group at 9.2 months.

Conclusion:

After laparoscopic TME, bladder dysfunction is seen in one-fifth of the patients, which recovers in the next 6 months to 1 year. Sexual dysfunction is observed in 75% of patients immediately after TME which improves to 55% over 9.2 months.

Keywords: Functional outcome, laparoscopy, rectal cancer, sexual dysfunction, total mesorectal excision, urinary dysfunction

INTRODUCTION

The results of surgical treatment of rectal cancer have improved over the past two decades due to accurate pre-operative staging; appropriate referral for neoadjuvant therapy and standardised precise surgical technique using the principles of total mesorectal excision (TME) are essential to achieve optimal outcomes.[1,2,3] The concept of TME is the key determinant for decreased the local recurrence and achieving better oncologic results in rectal cancer.[3,4,5] As the pelvic organs and autonomic nerves are closely placed to the rectum, even with nerve-sparing techniques, there is a risk autonomic nerve injury resulting in sexual and bladder dysfunction.[5,6] Damage to the superior hypogastric plexus or hypogastric nerves results in ejaculatory dysfunction, whereas injury to the pelvic splanchnic nerves or pelvic plexuses causes urinary and erectile complications.

Even with incorporation of autonomic nerve-preserving techniques in TME, urinary and sexual dysfunction remains recognised complications in 0–12 and 10–35% of patients, respectively.[7,8,9] Laparoscopic TME for rectal cancer has been recently added in the treatment of rectal cancer, with acceptable complication rates and short-term oncological outcomes comparable to those of open surgery.[10,11,12] However, data are limited with respect to the incidence of urinary or sexual dysfunction after laparoscopic TME in comparison with open TME.[13,14,15] There are no studies from Indian subcontinent addressing the sexual and urinary dysfunction following laparoscopic low anterior resection. The current study aimed to assess the sexual and urinary dysfunction among a consecutive series of male patients with rectal cancer who underwent laparoscopic TME for rectal cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

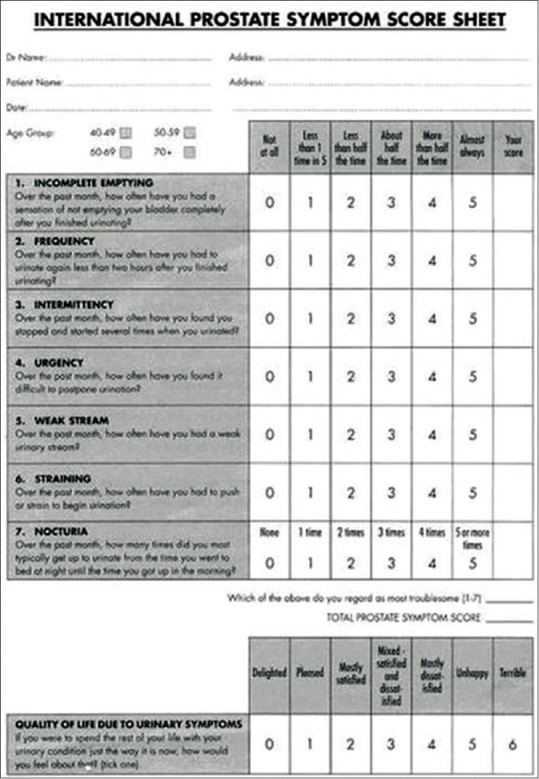

A prospective study was conducted between May 2014 and May 2016. The male patients aged 20–70 years with low and mid-rectal cancer who undergo laparoscopic nerve sparing TME during low anterior resection or abdominoperineal excision of rectum were included in the study. Patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0–2 and histologically confirmed carcinoma of the rectum (≤12 cm from anal verge) were included in this study. The bladder dysfunction was assessed using the International Prostatic Symptom Score (IPSS),[16] and sexual dysfunction was assessed using the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF).[17] The IPSS consists of seven questions to assess the occurrence of the following urinary symptoms in the previous 4 weeks [Figure 1]. In the IIEF questionnaire, a score of 0–5 is awarded to each of 15 questions that examine the 4 main domains of male sexual function: erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire and intercourse satisfaction. The maximum score for the erectile function domain is 30 and patients who scored ≤25 are considered to have erectile dysfunction.[18] All patients with a history of previous pelvic/rectal surgeries, emergency operation, those with history of impotence or retrograde ejaculation, those with severe urinary dysfunction (IPSS score >20), those with severe untreated physical or mental impairment and those with T4b disease or with inoperable metastasis were excluded from the study. Patients undergo uroflowmetry and post-voided residual (PVR) urine analysis preoperatively. They fill up the IPSS and IIEF questionnaire pre-operatively. Urinary catheterisation is done after the induction of anaesthesia.

Figure 1.

International Prostatic Symptom Score sheet

Laparoscopic nerve-sparing TME is performed by a single team which follows a strictly standardised surgical technique. Autonomic nerve preservation consists of the identification and preservation of the superior hypogastric and sacral splanchnic nerve trunks, together with the pelvic autonomic nerve plexus. The plane of pelvic dissection was chosen along the parietal pelvic fascia, and the left and right hypogastric nerves were identified. The lateral ligament was divided separating the intact mesorectum from the pelvic autonomic nerve plexus, leaving the sacral splanchnic nerve and the pelvic autonomic nerve plexus undamaged on the lateral pelvic wall. Dissection was performed using monopolar electrocautery and/or ultrasonic dissector. All rectal dissections were done by surgeons with >100 cases experience in laparoscopic rectal surgery.

A protective stoma was performed at the end of the low anterior resection as per the discretion of the surgeon. If the post-operative course is uneventful, urinary catheters are removed on day 5. If the patient goes in for retention after catheter removal, re-catheterisation will be done and drugs to enhance bladder function like bethanechol 25 mg twice daily will be started. In such cases, the patient is sent home on urinary catheter and asked to review after 2 weeks for trial removal of catheter. Patients subjected to IPSS and IIEF questionnaires, residual urine measurement and uroflowmetry 1, 3, 6 and 12 months following surgery.

Statistical methods

All continuous variables were described using mean and standard deviation. The relation between two continuous variables is estimated using Student's t-test. The value of P = 0.05 or <0.05 is taken as the level of significance. SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) software was used for the analysis of the data, and Microsoft Word and Excel have been used to generate graphs, tables, etc.

RESULTS

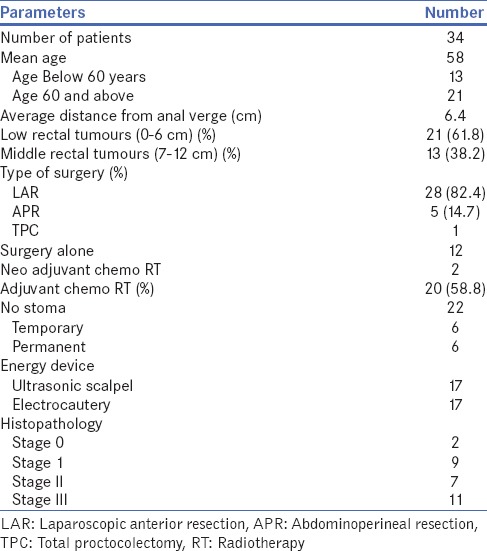

The study group of 34 patients had a mean age group of 58 years (range, 35–70 years) at the time of surgery. The tumour was located in the lower rectum (0–6 cm from anal verge) in 21 (61.8%) patients and mid-rectum (7–12 cm from anal verge) in 13 (38.2%) patients. The mean distance of the lesion from the anal verge of the entire cohort was 6.4 cm (range, 2–12 cm). Out of the 34 patients, 28 patients (82.4%) underwent Laparoscopic Anterior Resection (LAR), 5 patients (14.7%) had abdominoperineal resection and one patient with ulcerative colitis and rectal malignancy underwent total proctocolectomy. The patient demographic and clinical parameters are detailed in Table 1. Twelve patients (35%) underwent upfront surgery, 2 (6%) underwent long course chemoradiotherapy and 20 (59%) patients had post-operative chemoradiation therapy. In patients who underwent LAR, a covering stoma was done in 6 patients (21.4%), which were closed within 6–10 weeks later. Permanent stoma was done in six patients, five of them as part of APR and one patient with coloanal anastomosis who had pelvic sepsis and underwent re-exploration and permanent stoma. The mean post-operative hospital stay was 8.2 days (range 5–20 days) and mean follow-up was 9.2 months (range, 5–16 months). There was no 30 days mortality.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients

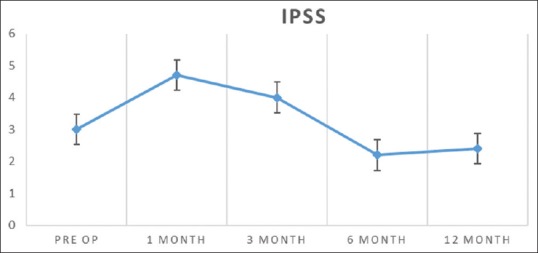

International Prostatic Symptom Score

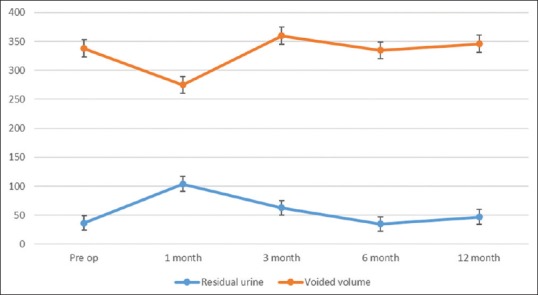

There was an increase in IPSS score, increase in residual urine and decrease in voided volume in the 1st month, which improves in the next 3–6 months post-operative period [Figure 2]. Four (8.8%) patients had moderate urinary dysfunction preoperatively. Following surgery at 1 month, 10 patients (29.4%) had moderate to severe dysfunction, which was seen in 7 patients (20.4%) at 3 months, 2 patients (5.8%) at 6 months and 1 (2.9%) at 1 year, respectively. The mean IPSS score of study population before surgery was 3 ± 4.6 which increased to 4.7 ± 5.4 in the 1st month follow-up. By the 3rd month, the IPSS score decreased to 4 ± 4.3, and by 6 months, the score was 2.2 ± 2.8 [Figure 2]. The voided volume of urine decreased from a mean pre-operative volume of 338–275 ml in 1st month. The voided volume improved in the next 3 months to a mean output of 346 ml at 1 year. The PVR remained elevated in the first (104 ± 108 ml) and 3rd month (63 ± 73 ml) review when compared to pre-op levels (36 ± 31 ml) but came back to normal levels by 6 months (35 ± 30 ml) [Figure 3]. The average peak flow rate and the mean flow volumes did not vary much during the follow-up period. After the surgery, 27 (79.4%) patients passed urine normally after catheter removal on the 5th post-operative day, and two patients had delayed catheter removal due to major deviation from normal post-operative course in the first 5 post-operative days (one patient with pelvic sepsis and another patient with staple line bleed). Five patients (14.7%) had urinary retention after catheter removal on day 5 and they were re-catheterised. No patient required permanent or intermittent catheterisation.

Figure 2.

International Prostatic Symptom Score of the study cohort

Figure 3.

Voided volume and post-voided residual urine

Nine patients (26.5%) required drugs to enhance bladder function during the initial follow-up period which included the 5 patients who had urinary retention and 4 patients who had voiding symptoms at 1st month follow-up. None of them required medications at 6 months. No patient had severe urinary dysfunction (IPSS >19) post-operatively.

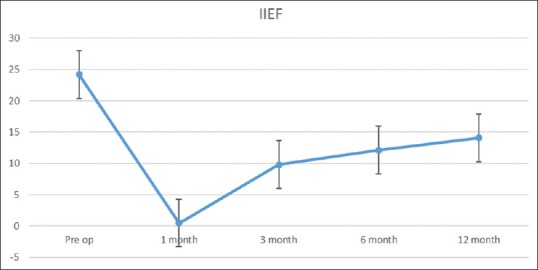

International Index of Erectile Function score

The IIEF score decreased in the 1st month which made a recovery over next 3–6 months. The mean pre-operative IIEF score was 24.2 ± 9.7 and it dropped to 0.5 ± 2.7 at 1 month. The mean IIEF scores at 3, 6 and 12 months were 9.8 ± 12.2, 12.1 ± 12.7 and 14.1 ± 13.8, respectively [Figure 4]. Among the twenty patients who were sexually active before surgery, 17 patients completed their 6 months’ review during which 7 patients (41.2%) resumed their sexual activities including erection, penetration, ejaculation and feeling of climax. Six patients (35.3%) had impaired sexual activity though they were able to achieve erection and one of them had retrograde ejaculation. Four patients (23.5%) could not achieve erections at 6 months. At median follow-up on 9.2 months, 45.5% of patients have normal sexual life and rest had sexual dysfunction (36.4%) or impotence (18.1%). At 1 year, 58.3% were enjoying normal sexual life, 25% had sexual dysfunction and 11.7% of them remained impotent.

Figure 4.

International Index of Erectile Function score of the study cohort

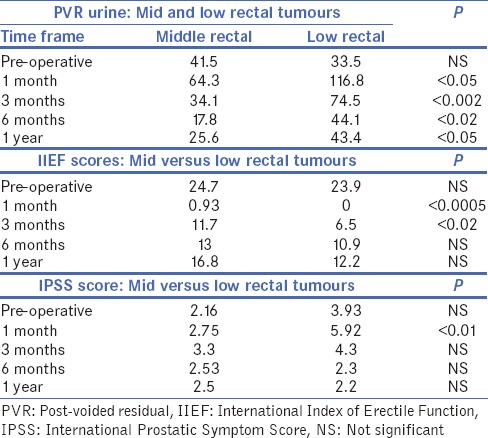

In the patients with low rectal lesions, the PVR remained significantly high at 6 months (44.1 vs. 17.8 ml; P < 0.02) and 1 year (43.4 vs. 25.6 ml; P < 0.05) when compared to mid-rectal lesions [Table 2]. The IPSS scores at 1 month (5.9 vs. 2.8; P ≤ 0.01) and 3 months (4.3 vs. 3.3; P = ns) remained higher in low rectal lesions but the difference did not attain statistical significance. The IIEF scores were significantly low at 1 month (0 vs. 0.9; P ≤ 0.0005), 3 months (6.5 vs. 11.7; P ≤ 0.02) and then remained non-significant even though the scores were low in low rectal when compared to mid-rectal lesions [Table 2].

Table 2.

The International Prostatic Symptom Score, International Index of Erectile Function score and post-voided residual of mid and low rectal lesions

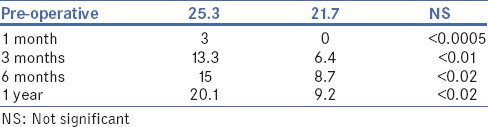

Patients who had post-operative stoma had a statistically significant higher IPSS score (7.5 vs. 3.1; P < 0.01) in 1st month follow-up when compared to patients with no stoma, but it was comparable in subsequent follow-ups. At 6 months follow-up, patients with stoma had a poorer IIEF score (8.2 vs. 15.3; P < 0.05), but at 1 year follow-up, the IIEF scores in patients with and without stoma were comparable.

In patients who had chemoradiation, their IPSS scores were better than patients who underwent surgery alone at 6 months (1.5 vs. 3.1; P < 0.05) and 12 months (1.5 vs. 3.4; P < 0.05) follow-up. The PVR was significantly high at 1 year follow-up in patients with chemoradiation when compared to patients who underwent surgery alone (28.1 vs. 68.2 ml; P < 0.02). The IIEF scores were significantly low in patients who underwent chemoradiation at from 1st month to 1 year period [Table 3].

Table 3.

International Index of Erectile Function score: Surgery versus chemoradiation

DISCUSSION

The concept of TME, which includes anatomical dissection of the pelvic fascia and recognition of vascular and nerve structures, has become a standard of care in rectal cancer surgery.[5,6,19] While performing radical surgery for rectal cancer, the chances of autonomic nerve injury are due to the injury to either the inferior hypogastric plexus or the pelvic splanchnic nerves due to violation of the avascular plane between the visceral and parietal pelvic fascia resulting in bladder and sexual dysfunction.[6,7,20] Laparoscopic TME has potential advantages over laparotomy due to the image magnification and the 30° angle eyepiece.[21,22] The sympathetic component is recognised in >90% of cases and the parasympathetic component in 53%–96% due to the deeper location of parasympathetic nerve and its branches in the pelvis.[22,23] However, whether the use of laparoscopic technique means less sexual or bladder dysfunction is not conclusively demonstrated in the clinical trials.[13,14,15] Unless the functional assessment is performed using dedicated questionnaire/scores, the incidence of this functional morbidity remains underestimated. In the current study, validated questionnaires were sued and parameters including residual urine and PVR volumes to have and objective assessment. In our study, at 3 months of follow-up, 20.4% of patients had mild urinary dysfunction (IPSS <8), and at mean follow-up of 9.2 months, it had improved to 2.9%. At 3 months, 75% had sexual dysfunction, 59% at 6 months and 55% at median follow-up of the group at 9.2 months, and at 1 year follow-up, it was 41.6%. This is in comparison with the published literature.[16,22,23]

In this study, the IPSS score preoperatively was 3 ± 4.6 which increased to 4.7 ± 5.4 in the 1st month review. This may be due to the neuropraxia of pelvic nerves, especially the parasympathetic. The sympathetic components are more often identified and preserved as they lie outside pelvis on the aorta and close to sacral promontory. The parasympathetic components lie deep within the pelvis and injury to these cause increase in residual urine and voiding symptoms of bladder denervation. This deterioration of bladder function recovers over time if the nerves are not fully severed. Most of the patients recovered by 3 months who evidenced by the decreasing IPSS values (4 ± 4.3) and almost all of them recovered by 6 months (IPSS 2.2 ± 2.8). The mean age of the study group was 58 years in our study and this age group is prone for age-related urogenital issues in the form of prostatic enlargement and erectile dysfunction. Mild to moderate erectile dysfunction is observed in 50%–60% of patients at 60 years. Only 20 (58.8%) out of 34 patients were sexually active in our study. Hence, comparison of pre-operative scores with post-operative values is very important. The IIEF scores were low at 3 months and further scores steadily improved to 9.8 at 3 months to 14.1 at 1 year. However, the scores (24.2) never reached to the pre-operative values. The psychological trauma of diagnosing a malignancy, the pre-operative chemoradiation and the repeated hospital visits adversely affect the IIEF scores and this effect continues in the post-operative period.[14,22] Other factors that come into picture in the post-operative period include the increasing bowel movements, adjuvant treatment and stoma and in some situations the post-operative morbidity. All these factors could affect the sexual function adversely apart from possible neurological injury. It is our experience that even when the physical tiredness and psychological stress is overcome by the patient, but his spouse may not be willing for sex in the post-operative period.

The PVR and flow rates did not correspond to the clinical symptoms in all cases. Some patients had elevated PVR urine with no urinary symptoms including a normal IPSS score. Kim et al.[24] reported a slightly different result in 2002 where he reported a change in mean maximal flow rate and voided volumes with normal residual urine volume. None of the studies have reported 1 month review for analysing urogenital dysfunction and some studies have delayed their analysis up to 27 months.[22] This should be due to the fact that in patients with urinary dysfunction, 1 month time is not enough for the neuropraxia to recover. However, this 1 month review and urinary analysis help to detect a subset of patients with urinary issues which were not detected in the immediate post-operative period and start them on drugs to enhance bladder function as early as possible. The scores improved in the 3rd month (4 ± 4.3) and reached normal or pre-operative levels by 6 months. The obstructive component like prostatic hypertrophy also alters the uroflowmetry, residual urine and IPSS score. To differentiate, this from the inadequate bladder wall contraction as a result of parasympathetic damage requires urodynamic studies, which we have not done in our study due to technical reasons. The pre-operative obstructive component improves with medications and this should be the reason for lower IPSS score (lower than pre-operative value [3 ± 4.6]) at 6 months follow-up (2.2 ± 2.8).

In a subset analysis comparing low rectal lesions with mid-rectal tumours, the PVR levels remained high at 6 months (44.1 vs. 17.8 ml; P < 0.005) and 12 months (63.4 vs. 25.6 ml; P < 0.05). This may be due to more chance for neuropraxia when dissection is continued deep into the pelvis, especially in anterior lesions.[9,20] Even though the IPSS scores were higher in low rectal tumours, it remained non-significant after 6 months and probably might turn out to be significant when the number of cases increase in our study. A previous study[25] showed a trend towards greater impairment of post-surgical spontaneous erectile function in rectal cancer <7 cm from the anal verge, but this difference was not statistically significant. In our case series, the IIEF scores’ difference between low and mid-rectal tumours was statistically non-significant after 6 months.

In comparison with those had no chemoradiation versus chemoradiation, showed significant lowering of IIEF scores throughout their follow-up when compared to patients who had no chemoradiation (20.1 vs. 9.8; P < 0.02 at 1 year). Previous studies[24,26] have reported poor functional outcome after radiation. Due to monthly chemotherapy and associated morbidity, their sexual drive will definitely be reduced until the 6 months’ review. The radiation-induced neuronal damage or delay in recovery from neuropraxia due to surgery may contribute to these findings.

Our study has following limitations. The mean age group of the patients was 58 years, and at this age, a proportion of patients have already sexual and bladder dysfunction. A number of our study patients are relatively small and more patients with low rectal tumours in a relatively younger age group would have given better data. Inherent problems in assessing sexual dysfunction in patients such as psychosocial factors, subjective nature of the responses to the questions, spouse not cooperating, etc., would have affected our study as well. Finally, a longer follow-up data with more study patients would have provided more meaningful data. Despite all these factors, this is the first of its kind of data of sexual and bladder dysfunctions assessed objectively in male patients undergoing laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery in the Indian context

CONCLUSION

After laparoscopic TME in male patients, the moderate to severe bladder dysfunction (IPSS <8) is observed in 20.4% of patients at 3 months, and at mean follow-up of 9.2 months, it was seen only in 2.9%. There is more bladder and sexual dysfunction in low rectal tumours when compared to mid-rectal tumours. At 3 months, 75% had sexual dysfunction and 55% at median follow-up of the group at 9.2 months, and at 1 year follow-up, it was 41.6%. Studies with a larger number of patients with relatively young age group and longer follow-up are required for more meaningful data.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heald RJ, Moran BJ, Ryall RD, Sexton R, MacFarlane JK. Rectal cancer: The Basingstoke experience of total mesorectal excision, 1978-1997. Arch Surg. 1998;133:894–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.8.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunderson LL, Sargent DJ, Tepper JE, Wolmark N, O'Connell MJ, Begovic M, et al. Impact of T and N stage and treatment on survival and relapse in adjuvant rectal cancer: A pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1785–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosinski L, Habr-Gama A, Ludwig K, Perez R. Shifting concepts in rectal cancer management: A review of contemporary primary rectal cancer treatment strategies. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:173–202. doi: 10.3322/caac.21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enker WE. Potency, cure, and local control in the operative treatment of rectal cancer. Arch Surg. 1992;127:1396–401. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420120030005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heald RJ. Total mesorectal excision: History and anatomy of an operation. Rectal Cancer Surgery: Optimisation – Standardisation – Documentation. In: Soreide O, Norstein J, editors. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 1997. pp. 203–19. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Havenga K, Enker WE, McDermott K, Cohen AM, Minsky BD, Guillem J. Male and female sexual and urinary function after total mesorectal excision with autonomic nerve preservation for carcinoma of the rectum. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;182:495–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enker WE, Havenga K, Polyak T, Thaler H, Cranor M. Abdominoperineal resection via total mesorectal excision and autonomic nerve preservation for low rectal cancer. World J Surg. 1997;21:715–20. doi: 10.1007/s002689900296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masui H, Ike H, Yamaguchi S, Oki S, Shimada H. Male sexual function after autonomic nerve-preserving operation for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1140–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02081416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nesbakken A, Nygaard K, Bull-Njaa T, Carlsen E, Eri LM. Bladder and sexual dysfunction after mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2000;87:206–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartley JE, Mehigan BJ, Qureshi AE, Duthie GS, Lee PW, Monson JR. Total mesorectal excision: Assessment of the laparoscopic approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:315–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02234726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prakash K, Varma D, Rajan M, Kamlesh NP, Zacharias P, Ganesh Narayanan R, et al. Laparoscopic colonic resection for rectosigmoid colonic tumours: A retrospective analysis and comparison with open resection. Indian J Surg. 2010;72:318–22. doi: 10.1007/s12262-010-0119-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pikarsky AJ, Rosenthal R, Weiss EG, Wexner SD. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:558–62. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayne DG, Brown JM, Thorpe H, Walker J, Quirke P, Guillou PJ. Bladder and sexual function following resection for rectal cancer in a randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open technique. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1124–32. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersson J, Angenete E, Gellerstedt M, Angerås U, Jess P, Rosenberg J, et al. Health-related quality of life after laparoscopic and open surgery for rectal cancer in a randomized trial. Br J Surg. 2013;100:941–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim RS, Yang TX, Chua TC. Postoperative bladder and sexual function in patients undergoing surgery for rectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open resection of rectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:993–1002. doi: 10.1007/s10151-014-1189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr, O'Leary MP, Bruskewitz RC, Holtgrewe HL, Mebust WK. The American Urological Association symptomc index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The measurement committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–30. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cappelleri JC, Rosen RC, Smith MD, Mishra A, Osterloh IH. Diagnostic evaluation of the erectile function domain of the International Index of Erectile Function. Urology. 1999;54:346–51. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.How P, Shihab O, Tekkis P, Brown G, Quirke P, Heald R, et al. Asystematic review of cancer related patient outcomes after anterior resection and abdominoperineal excision for rectal cancer in the total mesorectal excision era. Surg Oncol. 2011;20:e149–55. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moszkowicz D, Alsaid B, Bessede T, Penna C, Nordlinger B, Benoît G, et al. Where does pelvic nerve injury occur during rectal surgery for cancer? Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1326–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGlone ER, Khan O, Flashman K, Khan J, Parvaiz A. Urogenital function following laparoscopic and open rectal cancer resection: A comparative study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2559–65. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sartori CA, Sartori A, Vigna S, Occhipinti R, Baiocchi GL. Urinary and sexual disorders after laparoscopic TME for rectal cancer in males. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:637–43. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1459-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keating JP. Sexual function after rectal excision. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:248–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2004.02954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim NK, Aahn TW, Park JK, Lee KY, Lee WH, Sohn SK, et al. Assessment of sexual and voiding function after total mesorectal excision with pelvic autonomic nerve preservation in males with rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1178–85. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morino M, Parini U, Allaix ME, Monasterolo G, Brachet Contul R, Garrone C. Male sexual and urinary function after laparoscopic total mesorectal excision. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1233–40. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birgisson H, Påhlman L, Gunnarsson U, Glimelius B, Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial Group. Adverse effects of preoperative radiation therapy for rectal cancer: Long-term follow-up of the Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8697–705. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]