Abstract

Background:

Laparoscopic hepatic bisegmentectomy (s4b and s5) with regional lymphadenectomy (LHBRL) for patients with gallbladder cancer (GBC) is rarely reported.

Aims:

The aim of the study was to describe the technique of LHBRL in patients with GBC and to present our initial experience.

Patients and Methods:

This retrospective study was conducted on twenty patients with GBC who were considered for LHBRL by the described technique. These patients either had a suspicion of GBC (SGBC) or had an incidental diagnosis of GBC (IGBC). Appropriate statistical methods were applied.

Results:

Twelve patients (60%) had SGBC and eight patients (40%) had IGBC. Eighteen patients (90%) were females and median age was 50 (range: 28–70) years. Median (range) surgical blood loss was 120 ml (80–400), operation time was 300 (200–480) min and hospital stay was 5.5 (2–10) days. No patient had iatrogenic complication during LHBRL. Five (25%) patients required conversion to open method. Four patients (20%) who developed complications were managed conservatively. All but three patients (25%) with SGBC had a benign disease on final biopsy. TNM stage of 17 patients (85%) with adenocarcinoma was T1bN0 in 3 (17.6%), T2N0 in 6 (35.3%), T3N0 in 2 (11.7%) and T1-3N1 in 6 (35.3%). The median lymph node count was 10 (range: 4–24) and resection margins were negative (R0) in all. The overall survival was 82.3%. During a median follow-up of 22 months, two patients died due to disease recurrence and one patient died due to myocardial infarction.

Conclusion:

The described technique of LHBRL is safe and feasible for patients with GBC without extrahepatic involvement.

Keywords: Bisegmentectomy, cholecystectomy, extended, gallbladder cancer, laparoscopy, radical

INTRODUCTION

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is the most common biliary tract malignancy in Indian females.[1] Prognosis of GBC has been poor due to aggressive nature of the disease and late presentation. Early detection and aggressive surgical treatment is the key to achieve a possible cure.[1] The surgical treatment of GBC is based on T stage, location of the tumour and involvement of portal structures.[2,3] Simple cholecystectomy is adequate for patients with T1a GBC whereas patients with T1b-T3 GBC require extended cholecystectomy (EC).[3,4] Patients with T4 GBC are usually unresectable due to nature of locoregional involvement and/or presence of distant metastasis.[1,3] Open surgical approach has been the ‘gold standard’ for the management of patients with GBC.[1] Recently, Gumbs et al. reported first successful laparoscopic EC (LEC) for a patient with GBC following which several authors have reported safety and feasibility of LEC in GBC.[5,6]

Like in open surgery, ‘standard’ LEC also includes an en bloc removal of gallbladder (GB) with a wedge of (usually 2 cm) liver and the regional lymph nodes (LNs) (N1).[2,3,4,5] Hepatic recurrence is the most common type of recurrence observed after both open and LEC.[1,3,7] Hepatic bisegmentectomy (s4b and s5) with regional lymphadenectomy may help to reduce the incidence of hepatic recurrence, especially in patients with T2-T3 GBC.[8,9] First laparoscopic hepatic bisegmentectomy with regional lymphadenectomy (LHBRL) was performed by Machado et al., but this patient had a benign disease on histological examination.[10] Recently, Palanisamy et al. used laparoscopic ultrasound (LUS) to perform LHBRL in 14 patients with suspected GBC (SGBC).[11] The purpose of this study was to describe our technique of LHBRL and share our initial experience.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

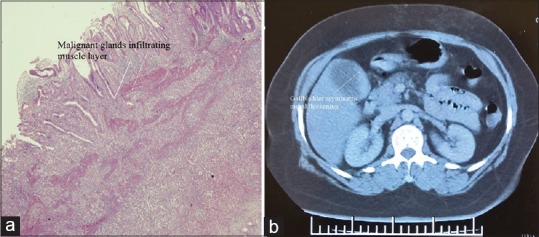

This retrospective study was conducted by a single surgical team working at a tertiary care centre in North India. The study period was from August 2010 to August 2015. The written informed consent was obtained from all the patients. As per institutional guidelines, approval from the Ethics Committee was not necessary. The study included two types of patients; the patients with incidental GBC (IGBC) which was detected after histological examination of GB specimen following cholecystectomy and the patients who had SGBC on contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen [Figure 1a and b]. Patients with suspected involvement of neck of the GB, involvement of extrahepatic organs and distant metastasis were excluded from the study.

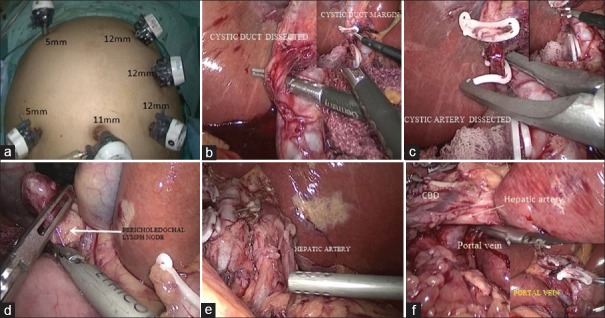

Figure 1.

(a) Microscopic picture of a patient with T2 incidental gallbladder cancer; (b) computerised tomography picture of a patient with suspected gallbladder cancer

Our pre-operative protocol included complete blood counts, liver function test (LFT), renal function test, international normalised ratio, serum markers for viral hepatitis B and C, serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), ultrasound (US) of the abdomen and CECT of the abdomen. Endoscopic ultrasound was performed in a patient with advanced locoregional disease and/or in patients with suspected metastasis to distant LNs (M1). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography was advised in patients with clinical and/or laboratory and/or radiological suspicion of bile duct involvement. Staging laparoscopy (SL) was performed in all the patients. American Joint Committee on Cancer seventh edition classification system was used for disease stratification.[2] Dindo et al. classification was used to classify severity of postoperative complications.[12]

Technique of laparoscopic hepatic bisegmentectomy with regional lymphadenectomy

Patients were placed in reverse Trendelenburg's position with legs apart. Pneumoperitoneum was created by Hassan's technique and total five or six laparoscopic access ports (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, USA) were used [Figure 2a]. The camera assistant was between the legs and the surgeon was on the left side of the patient. The intra-abdominal pressure during whole surgery was from 10 to 12 mmHg. The central venous pressure during hepatic resection was below 5 mmHg. Harmonic scalpel (Gen 4, Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, USA) was used for dissection and transaction of hepatic parenchyma. Blood vessels smaller than 3 mm were divided with harmonic scalpel, and vessels of larger size were ligated with LIGACLIP (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, USA) before division. Fenestrated atraumatic endoscopic forceps (KARL STORZ, Germany) was used to hold GB during the dissection of hepatocystic triangle. Non-fenestrated atraumatic forceps (KARL STORZ, Germany) was used to hold falciform ligament for retraction. Hem-o-lok clips (Teleflex medicals, Durham, NC, USA) were used to secure cystic duct before division.

Figure 2.

(a) Port placement; (b) cystic duct ligation with inset showing excision cystic duct margin; (c) cystic artery ligation and division; (d) showing excision of pericholedochal lymph node; (e) hepatic artery after lymph node excision; (f) portal vein after lymph node excision with inset showing contralateral side of portal vein

SL was performed through the umbilical port (30°, 10 mm telescope, three-chip camera, make-KARL STORZ, Germany), and suspicious metastatic lesions were sampled for frozen biopsy. Patients with resectable disease on SL were further assessed. Patients with obscured anatomy of hepatocystic triangle (Calot's triangle) and involvement of surrounding organs were converted to open surgery. In patients with SGBC, hepatocystic triangle was dissected to delineate and divide cystic duct after securing with Hem-o-lok clips, and cystic duct margin was obtained for frozen biopsy [Figure 2b with inset]. Cystic artery was also dissected and divided carefully [Figure 2c with inset]. In the next step, liver was retracted upwards and towards the left diaphragm by the second assistant and surgeon's left hand was used for counter traction during further dissection. Pericholedochal LNs were dissected away from the whole length of bile duct [Figure 2d]. LNs around hepatic artery and its branches also excised in the similar fashion [Figure 2e]. LNs around portal vein were dissected both from left and right side [Figure 2f]. All the steps were similar in patients with IGBC except no dissection of hepatocystic triangle was required in these patients.

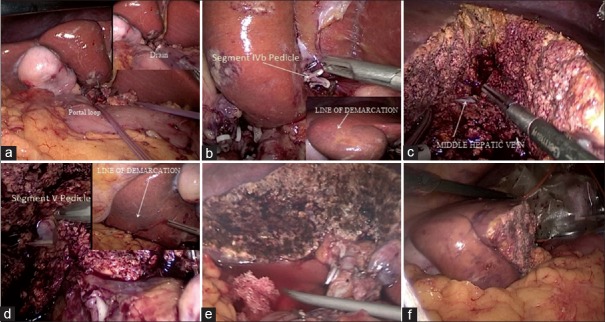

After LN excision (N1), a feeding catheter (10 F, Romosons, India) was passed through the epiploic foramen to encircle the portal structures and both the ends of feeding tube were brought out through a drain tube (32–36 F, Romsons, India) [Figure 3a]. One end of drain tube containing the both ends of the feeding tube was outside the abdomen, and this was used for Pringle's manoeuvre during deep hepatic transaction. Falciform ligament was now retracted downwards (caudal) and towards left iliac fossa to facilitate dissection of portal pedicle of hepatic segment 4b (s4b) inside the umbilical fissure. Portal pedicle to s4b was divided after test clamping to avoid injury s4a portal pedicle [Figure 3b with inset]. The transaction of hepatic parenchyma was done along the s4b demarcation line until middle hepatic vein (MHV) was reached, MHV served as a landmark between 4s and s5 [Figure 3c]. Further dissection towards hepatic hilum exposed s5 portal pedicle which was divided after test clamping and parenchyma transaction along s5 demarcation line was performed to complete the hepatic resection [Figure 3d with inset]. The raw surface of liver was cleaned with normal saline to check for bile leak and major bleeding [Figure 3e]. The oozing from the raw surface was controlled by surface coagulation by spray mode of the monopolar diathermy (KARL STORZ, Germany]). Any significant bleeding or bile leak was controlled with polyglactin 3-0 (Vicryl, Ethicon, USA) sutures. Resected specimen was transferred to an Endobag (Covidien, USA) for extraction through a small subcostal incision (5–6 cm) on the right side [Figure 3f]. The abdominal wounds were closed in layers after positioning a drain (32 F, Romsons, India) in the right subhepatic space.

Figure 3.

(a) A loop passed through the foramen Winslow with inset showing both ends inside a drain tube; (b) segment 4a portal pedicle with demarcation line in inset; (c) exposed middle hepatic vein after transaction of hepatic parenchyma of segment s4b; (d) portal pedicle of segment 5 with inset showing demarcation; (e) raw surface of liver after completion of bisegmentectomy; (f) specimen after completion of bisegmentectomy

Statistical analysis

Statistical package SPSS version 22 for Windows (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the analysis. Numerical data were represented as median and range. Categorical and ordinal data were represented as percentages.

Follow-up and adjuvant treatment

First follow-up visit was at 2 weeks, second visit was at 6 weeks and thereafter patients visited to outpatients department at every 3 months for the first 2 years. After the 2 years, patients visited us at every 6 months for the follow-up. Clinical examination, LFT, tumour markers (CA 19-9 and CEA) and US of the abdomen were advised at every visit. CECT of the abdomen and fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography scan were advised in patients with raised tumour markers or in patients with suspicion of recurrence on US of the abdomen. Patients were referred to the Medical Oncology Department after the discharge from our unit for chemotherapy.

RESULTS

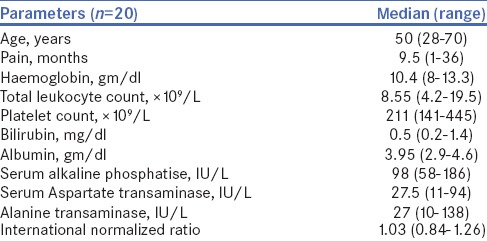

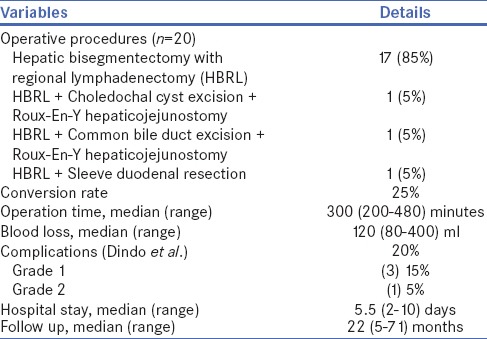

Eighteen (90%) out of total 20 patients were females and median age was 50 years. Pain in abdomen was a prominent symptom in all the patients and the duration of pain was from 1 to 36 months. No patient had clinical and/or laboratory signs of bile duct obstruction [Table 1]. Twelve (60%) patients had SGBC and 8 (40%) patients had IGBC. LHBRL was successful in 15 (75%) patients whereas 5 (25%) required conversion to open method. Reasons for conversion were obscured anatomy and involvement of the extrahepatic organs [Table 2]. No patients had iatrogenic complications during LHBRL, but free stones were found inside the peritoneal cavity of the two patients with IGBC both had laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) elsewhere. Median surgical blood loss and duration of surgery were 120 ml and 300 min, respectively. Total 4 (20%) patients had post-operative complication (Grade 1 and 2), all were managed conservatively. There was no 30-day hospital mortality [Table 2].

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

Table 2.

Operative and postoperative details

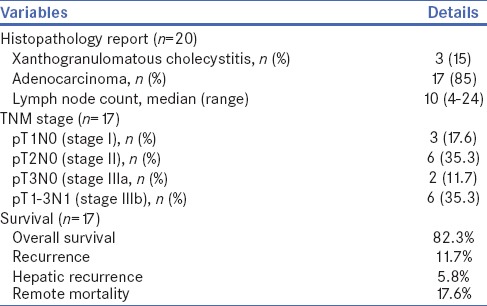

Histological examination of the resected specimen showed xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis in three patients (15%), adenocarcinoma in 17 patients (85%) and median LNs count was 10 [Table 3]. Amongst 17 patients with adenocarcinoma, majority (82.3%) had Stage II/III disease and overall survival was 82.3%. Out of two patients with GB perforation during LC (at other hospitals), one patient with T2N1 disease was died due to peritoneal recurrence after 5 months of LHBRL. Another patient of IGBC with GB perforation had T1bN0 disease and she died due to myocardial infarction after 18 months of surgery; we could not establish recurrence of GBC in this patient. One patient with SGBC (T3N1) died due to hepatic and lymph nodal recurrence after 12 months of surgery. The median follow-up of the study was 22 months (range: 5–71) and total 3 (17.6%) patients died during this period [Table 3].

Table 3.

Histopathology, TNM stage and survival

DISCUSSION

Our technique of LHBRL was similar to the technique described by Machado et al., and with this technique, anatomical resection of s4b and s5 can be achieved without the use of the LUS.[10,11] In this technique, hepatic transaction was guided by demarcation lines after the ligation of segmental portal pedicles and MHV serves as intrahepatic landmark between s4b and s5. Utmost care should be taken to avoid GB perforation to prevent peritoneal seeding of the tumour cells. We practised a low threshold for conversion to avoid risk of iatrogenic complications. The safety and feasibility of laparoscopic excision of the extrahepatic organs in patients with biliary malignancy has been described but, to ensure patient safety, we converted such patients to open surgery.[13] GB perforation, bile leak and excessive bleeding are associated with potential risk seeding dissemination of malignancy, and this risk is relatively high laparoscopic surgery.[14,15,16] However, in patients with early GBC, results of laparoscopic surgery have been equivalent to open surgery.[11,17] In the absence of other risk factors, laparoscopic surgery per se have not been associated with poor prognosis.[18] In our opinion, proper patients’ selection, good surgical technique and a low threshold for conversion are necessary to ensure patient safety in laparoscopic management of the GBC.

We encountered early recurrence in a patient with GB perforation at the time LC, but it was difficult to establish that it occurred due to peritoneal seeding or due to the presence of micrometastasis well before LC because this patient had LN positive (T2N1) disease. LN metastasis is a known poor prognostic factor in patients with GBC.[19] The extent of hepatic resection in patients with GBC has been variable from few millimetres to anatomical bisegmentectomy.[3,4,6,7,8] However, it is believed that anatomical resection of s4b and s5 provides better biliovascular control and a safer hepatic margin.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8] The chances of leaving behind micrometastasis are less with anatomical resection than with wedge hepatectomy.[8,9,14,16] In the present study, incidence of hepatic recurrence was low (5.8%) which could be due to improved hepatic margin in LHBRL, but it could also be due to a favourable tumour biology. A good patient survival and lack of serious post-operative complications may be a preliminary indication of oncological superiority on anatomical resection in GBC. However, it not fair to draw such conclusion on the basis of this single armed, retrospective study with limited sample size and follow-up. Further prospective trials and/or comparative studies will throw more light on this subject.[19,20,21]

Our study may be criticised for the inclusion of patients with T1b GBC because the risk of micrometastasis in these patients was very low and wedge (2 cm) hepatic resection could have been adequate. We agree that wedge hepatectomy (2 cm margin) is adequate for patients with confirmed diagnosis of T1b GBC, but these two patients with IGBC were not able to produce previous biopsy slides and tissue blocks for the review at our centre; therefore, we decided to go for s4b and s5 resection. According to our protocol, patients with a high SGBC on CECT and/or MRI are candidates for laparoscopic or open hepatic bisegmentectomy with regional lymphadenectomy (N1). Patients with circumferentially thick wall of GB and without hepatic infiltration are candidate en bloc resection of GB and a part of liver followed by frozen biopsy; regional LN excision is done only if required. Moreover, the facility of frozen biopsy was available only 9 am to 4 pm, and it was not feasible sometimes when surgery was delayed. Patient with benign biopsy report in our study either had a high pre-operative Suspicion of GBC or frozen biopsy was not possible.

CONCLUSION

The described technique of LHBRL is safe and feasible in patients with GBC without extra-hepatic involvement.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Puja Sakhuja, Professor and Head, Department of Pathology, GIPMER, New Delhi, for providing microscopic image of a patient with IGBC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kingham TP, D'Angelica MI. Cancer of the gallbladder. Blumgart's Surgery of the Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas. In: Jarnagin WR, editor. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. pp. 741–59e4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compton CC, Byrd DR, Gracia-Agular J, Kurtzman SH, Olawaye A, Washingon MK. 2nd ed. London: Springer; 2012. AJCC Cancer Staging Atlas: A Companion to the Seventh Editions of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual and Handbook; pp. 259–68. [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Angelica M, Dalal KM, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR. Analysis of the extent of resection for adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:806–16. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glenn F, Hays DM. The scope of radical surgery in the treatment of malignant tumors of the extrahepatic biliary tract. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1954;99:529–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gumbs AA, Milone L, Geha R, Delacroix J, Chabot JA. Laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:519–20. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho JY, Han HS, Yoon YS, Ahn KS, Kim YH, Lee KH. Laparoscopic approach for suspected early-stage gallbladder carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2010;145:128–33. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixon E, Vollmer CM, Jr, Sahajpal A, Cattral M, Grant D, Doig C. An aggressive surgical approach leads to improved survival in patients with gallbladder cancer: A 12-year study at a North American Center. Ann Surg. 2005;241:385–94. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000154118.07704.ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshikawa T, Araida T, Azuma T, Takasaki K. Bisubsegmental liver resection for gallbladder cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:14–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endo I, Shimada H, Takimoto A, Fujii Y, Miura Y, Sugita M, et al. Microscopic liver metastasis: Prognostic factor for patients with pT2 gallbladder carcinoma. World J Surg. 2004;28:692–6. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machado MA, Makdissi FF, Surjan RC. Totally laparoscopic hepatic bisegmentectomy (s4b+s5) and hilar lymphadenectomy for incidental gallbladder cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(Suppl 3):S336–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4650-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palanisamy S, Patel N, Sabnis S, Palanisamy N, Vijay A, Palanivelu P, et al. Laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy for suspected early gall bladder carcinoma: Thinking beyond convention. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2442–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gumbs AA, Jarufe N, Gayet B. Minimally invasive approaches to extrapancreatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:406–14. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo S, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Nagino M, Kanai M, Uesaka K, et al. Mode of tumor spread and surgical strategy in gallbladder carcinoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2002;387:222–8. doi: 10.1007/s00423-002-0318-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fong Y, Brennan MF, Turnbull A, Colt DG, Blumgart LH. Gallbladder cancer discovered during laparoscopic surgery. Potential for iatrogenic tumor dissemination. Arch Surg. 1993;128:1054–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420210118016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JM, Kim BW, Kim WH, Wang HJ, Kim MW. Clinical implication of bile spillage in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gallbladder cancer. Am Surg. 2011;77:697–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal AK, Javed A, Kalayarasan R, Sakhuja P. Minimally invasive versus the conventional open surgical approach of a radical cholecystectomy for gallbladder cancer: A retrospective comparative study. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:536–41. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goetze TO, Paolucci V. Prognosis of incidental gallbladder carcinoma is not influenced by the primary access technique: Analysis of 837 incidental gallbladder carcinomas in the German Registry. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2821–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2819-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shirai Y, Wakai T, Hatakeyama K. Radical lymph node dissection for gallbladder cancer: Indications and limitations. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2007;16:221–32. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Endo I, Takimoto A, Fujii Y, Togo S, Shimada H. Hepatic resection for advanced carcinoma of the gallbladder. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;99:711–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kai M, Chijiiwa K, Ohuchida J, Nagano M, Hiyoshi M, Kondo K. A curative resection improves the postoperative survival rate even in patients with advanced gallbladder carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1025–32. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]