Abstract

Laparoscopic and robotic hernia surgery offers advantages over open herniorrhaphy including faster recover and lower wound infection but is associated with rare but serious complications such as visceral injury and intestinal obstruction. We describe two cases of small bowel obstruction with strangulation that occurred shortly after routine robotic hernia surgery. We define this rare type of strangulating internal hernia as a peritoneal pocket hernia and call attention to its diagnosis and management.

Keywords: Internal hernia, peritoneal pocket hernia, robotic herniorrhaphy

INTRODUCTION

Robotic hernia surgery is increasingly used among general surgeons for ventral and inguinal hernias.[1] Laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy is known to offer advantages over open hernia surgery including lower wound infection and reduced pain.[2] However, because of lack of closure of the facial defect and lack of excision of the hernia sac, laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy often results in persistent abdominal wall eventration, rectus diastasis and significant seromas, with a resultant displeasing and uncomfortable abdominal wall bulge.[3] In addition, laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy requires the placement of abdominal wall tacks or anchors which may cause chronic pain.[4] Robotic ventral herniorrhaphy addresses these problems by allowing for primary intra-corporeal suture repair of the facial defect (difficult or impossible to perform laparoscopically) before the placement of an underlay mesh.[5] In addition, robotic herniorrhaphy allows for easier adhesiolysis (especially of dense adhesions) and easier suture fixation, reducing the need for tacks and tack-associated neuralgia.

Use of robotic technology for inguinal herniorrhaphy is also used increasingly among general surgeons.[1] Laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy gained popularity in the 1990s, and today, it offers potentially a faster recovery and possibly lower chronic pain over open inguinal herniorrhaphy.[6] Unfortunately, recurrence rates have been shown to be higher compared to open anterior herniorrhaphy for primary inguinal hernias and major complications including intestinal obstruction while rare appears to be higher.[7] For this reason, laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy is still often reserved by many surgeons for recurrent and bilateral inguinal hernias.[8] Robotic inguinal herniorrhaphy, done via a trans-abdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) approach, offers some advantages over open and laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy. Robotic inguinal herniorrhaphy allows for easier sutured closure of the peritoneal pocket as an alternative to laparoscopic TAPP. In addition, in the re-operative setting where extensive adhesions might be encountered, robotic hernia repair offers easier and more delicate lysis of adhesions with more gentle reduction of chronically incarcerated small and large bowel.

Rare but serious complications that have been shown to occur with laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy, especially with the TAPP approach, include visceral injury and intestinal obstruction.[9] While the cause for early post-operative intestinal obstructions in these cases are often neither specifically identified nor captured in most of the published case series, we suspect that breakdown of the peritoneal pocket closure during TAPP can be an under-appreciated cause of a strangulating internal hernia and resultant small bowel obstruction. We define this problem as a peritoneal pocket hernia (PPH). It is a distinct form of an internal hernia that may put patients at risk of intestinal obstruction and strangulation. Likewise, breakdown of a sutured closure of a peritoneal pocket during robotic hernia surgery may result in a similar strangulating PPH. This complication occurring after robotic hernia repairs has only been rarely reported in the literature[10] and we sought to share our experience with two robotic hernias cases – one robotic TAPP bilateral inguinal hernia repair and another robotic incisional hernia repair. In both cases, a strangulating PPH with intestinal obstruction occurred early after surgery and required reoperation. We suspect that sutured closure of the peritoneal pocket with barbed suture contributed further to the strangulating effect of the peritoneal pocket.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

The patient is a 73-year-old man with a history of three previous open right inguinal hernia repairs at other institutions as well as a robotic prostatectomy who presented with a recurrent right and symptomatic left inguinal hernia. Given the patient's history of multiple prior open hernia surgeries, we initially favoured a laparoscopic approach. Given the history of robotic prostatectomy with a post-operative pelvic haematoma and the likelihood of adhesions, we decided on a robotic TAPP approach, which would allow for easier lysis of adhesions, reduction of the hernia sac and sutured closure of the peritoneal pocket.

On insufflation of the abdomen, placement of robotic trocars and docking of the da Vinci Si system, a large right indirect inguinal hernia defect containing small bowel was visualised lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. The peritoneum was incised and the hernia sac reduced into the peritoneal cavity with subsequent development of a pre-peritoneal pocket. An extra-large Bard 3DMax polypropylene mesh (12.4 cm × 17.3 cm) was tacked into place to the pubic tubercle and onto the anterior pubic ramus at Cooper's ligament. The peritoneal defect was then closed using 2-0 absorbable V-Loc (barbed) suture in a running fashion. The left-sided hernia was repaired in the same manner.

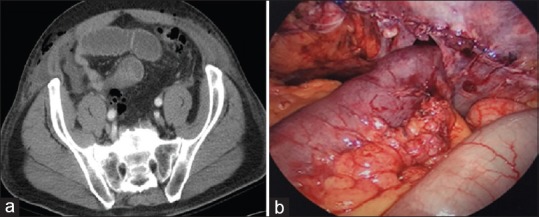

The patient was discharged home on the same day after surgery but returned to the emergency room on the 2nd post-operative day with complaints of significant abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and obstipation. He was diffusely tender on abdominal examination and a computed tomography (CT) scan [Figure 1a] was performed demonstrating a high grade closed-loop small bowel obstruction with a transition point in the right lower quadrant. The patient was urgently taken to the operating room where he underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy. The peritoneal closure on the right had dehisced, and a loop of small bowel had incarcerated within it [Figure 1b] which upon reduction appeared bruised but viable. The peritoneum was attenuated and did not hold sutures well, so the peritoneal pocket was packed with Surgicel Nu-Knit to obliterate the dead space and prevent re-incarceration and then repaired using 0-silk figure-of-eight sutures using the Endo Stitch device. The patient's hospital course thereafter was significant for a 10-day ileus which eventually resolved. At 12-month follow-up, there was no evidence of recurrent inguinal hernia, no chronic pain and no recurrent intestinal obstruction.

Figure 1.

(a) Axial computed tomographic image showing small bowel obstruction with transition zone in the right lower quadrant at the site of an acutely incarcerated peritoneal pocket hernia. (b) Laparoscopy image showing small bowel incarcerated inside of a peritoneal pocket hernia 2 days after robotic trans-abdominal pre-peritoneal inguinal herniorrhaphy

Case 2

The patient is a 43-year-old woman with a history of a right hemicolectomy with end ileostomy for perforated Meckel's diverticulitis with peritonitis with subsequent reversal 18 years prior while in her native country of Ecuador. She developed an incisional hernia at her previous ileostomy site in her right hemi-abdomen and was brought in for elective repair. We chose to proceed with a robotic approach as an alternative to laparoscopy to allow for improved lysis of adhesions and to provide for sutured repair of the defect to reduce post-operative eventration. The robotic trocars were then placed and the da Vinci Xi system was docked. There were extensive filmy and dense adhesions, for which extensive lysis of adhesions was performed. There several loops of small bowel were noted within the hernia sac and adherent to the right anterior abdominal wall. These were carefully taken down using the robotic shears. The hernia defect which measured 5 cm was subsequently sutured closed using running 0-absorbable V-Loc suture after decreasing the intra-abdominal insufflation to reduce tension on the abdominal wall. The defect was further repaired with an 11.4 cm underlay mesh (the Bard Ventralight Echo PS system) in an intra-peritoneal onlay mesh fashion and was also sutured circumferentially with 0-Vicryl V-Loc suture.

The patient was admitted overnight and over the course of the evening became increasingly tachycardic with more abdominal pain and a lactate of 7.1 mmol/L. She underwent a CT scan that suggested an early post-operative recurrence and was taken back to the operating room urgently for a diagnostic laparoscopy. A segment of small bowel was found to be acutely incarcerated within a defect in the peritoneum lateral and superior to the sutured mesh. The bowel was carefully reduced and appeared bruised but viable, and we elected not to resect it. The peritoneum once again was attenuated and did not hold sutures well, so peritoneal pocket was packed with Surgicel Nu-Knit to obliterate the dead space and prevent re-incarceration and then closed using four interrupted 0-Vicryl sutures using the Endo Stitch. At 6-month follow-up, she has no recurrent incisional hernia, no port site hernia, no residual seroma, no abdominal wall eventration, no diastasis, no recurrent intestinal obstruction and no chronic pain.

DISCUSSION

Internal hernias are defined as protrusions though intra-abdominal defects and may be a cause of small bowel obstruction.[11] These internal hernias can include trans-mesenteric (e.g., after creation of a Roux-en-Y anastomosis or through a mesenteric defect after a bowel resection), paraduodenal (though a widened defect by the ligament of Treitz or Foramen of Winslow) and omental (through a defect in the omentum).[11] In this paper, we define another distinct class of internal hernia, the PPH. These hernias result from surgically created peritoneal defects that may incarcerate or strangulate the bowel. Such hernias may occur at laparoscopic port sites and within peritoneal pockets formed during laparoscopic or robotic hernia surgery.[12] In this paper, we first define PPH as a distinct clinical entity and we also describe two cases of PPH that occurred during robotic hernia surgery. We hypothesise that with the tight closure of the peritoneum, any small dehiscence of the peritoneal closure carries a risk of incarcerating the small bowel, causing possible obstruction and strangulation. We also hypothesise that barbed sutures might further add to the risk of strangulation by grabbing and trapping the small bowel within the peritoneal pocket, preventing the small bowel from self-reducing.[10]

Published literature has shown that early post-operative bowel obstruction may result from internal hernias including peritoneal defects at trocar sites.[11,12,13,14] Tears at the margin of TAPP repairs have also been shown to pose a threat of incarceration and possible strangulation.[12] Patients with these defects will often fail conservative non-operative management of their small bowel obstruction for this reason.[13] Some have noted the risk associated with torn peritoneal closure posing a higher risk of internal hernia incarceration and strangulation.[14]

In one of our cases, the peritoneal tear was not at the repaired defect site but lateral to the repair possibly due to increased tension on this lateral peritoneum due to large ‘bites’ of running barbed suture on the peritoneal defect. Smaller bites, reducing pneumoperitoneum, using smaller suture needles and suturing gently with the curvature of the needle, might reduce the risk of peritoneal tears during robotic herniorrhaphy.

In the re-operation for both of these cases, we were able to laparoscopically reduce the incarcerated bowel and repair the PPH by packing the dead space with Surgicel Nu-Knit absorbable oxidised regenerated cellulose and closing the tear with interrupted absorbable suture. We feel that the use of oxidised regenerated cellulose packing for torn peritoneal pockets, when the peritoneum will not hold sutures well, is a useful technique to avoid the risk of re-obstruction and incarceration. Oxidised regenerated cellulose is already a well-studied and well-established barrier layer (in addition to its haemostatic properties), safe and widely used in several commercially available coated meshes for intra-peritoneal underlay placement.

CONCLUSION

Intestinal obstruction and strangulation from a PPH are a rare but potentially dangerous complication after laparoscopic or robotic hernia repair. We suggest a high index of suspicion for strangulated PPH in patients undergoing routine elective robotic ventral or inguinal herniorrhaphy who present with early post-operative bowel obstruction.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tsui C, Klein R, Garabrant M. Minimally invasive surgery: National trends in adoption and future directions for hospital strategy. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2253–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2973-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forbes SS, Eskicioglu C, McLeod RS, Okrainec A. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing open and laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair with mesh. Br J Surg. 2009;96:851–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoenmaeckers EJ, Wassenaar EB, Raymakers JT, Rakic S. Bulging of the mesh after laparoscopic repair of ventral and incisional hernias. JSLS. 2010;14:541–6. doi: 10.4293/108680810X12924466008240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beldi G, Wagner M, Bruegger LE, Kurmann A, Candinas D. Mesh shrinkage and pain in laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: A randomized clinical trial comparing suture versus tack mesh fixation. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:749–55. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez AM, Romero RJ, Seetharamaiah R, Gallas M, Lamoureux J, Rabaza JR, et al. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with primary closure versus no primary closure of the defect: Potential benefits of the robotic technology. Int J Med Robot. 2015;11:120–5. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Memon MA, Cooper NJ, Memon B, Memon MI, Abrams KR. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1479–92. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neumayer L, Giobbie-Hurder A, Jonasson O, Fitzgibbons R, Jr, Dunlop D, Gibbs J. Open mesh versus laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal hernia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1819–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M, Bouillot JL, Campanelli G, Conze J, et al. European hernia society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia. 2009;13:343–403. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0529-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Reilly EA, Burke JP, O'Connell PR. A meta-analysis of surgical morbidity and recurrence after laparoscopic and open repair of primary unilateral inguinal hernia. Ann Surg. 2012;255:846–53. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824e96cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan FA, Hashmi A, Edelman DA. Small bowel obstruction caused by self-anchoring suture used for peritoneal closure following robotic inguinal hernia repair. J Surg Case Rep 2016. 2016:1–3. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjw117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blachar A, Federle MP. Internal hernia: An increasingly common cause of small bowel obstruction. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2002;23:174–83. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2171(02)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agresta F, Mazzarolo G, Bedin N. Incarcerated internal hernia of the small intestine through a re-approximated peritoneum after a trans-abdominal pre-peritoneal procedure – Apropos of two cases: Review of the literature. Hernia. 2011;15:347–50. doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0656-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Velasco JM, Vallina VL, Bonomo SR, Hieken TJ. Postlaparoscopic small bowel obstruction. Rethinking its management. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1043–5. doi: 10.1007/s004649900777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shpitz B, Lansberg L, Bugayev N, Tiomkin V, Klein E. Should peritoneal tears be routinely closed during laparoscopic total extraperitoneal repair of inguinal hernias? A reappraisal. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1771–3. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-9001-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]