Abstract

Background:

This study performed a literature analysis to determine outcomes of laparoscopic management in Müllerian duct remnants (MDRs).

Patients and Methods:

Literature was searched for terms ‘Müllerian’ ‘duct’ ‘remnants’ and ‘laparoscopy'. Primary end points were age at surgery, laparoscopic technique, intraoperative complications and postoperative morbidity.

Results:

The search revealed 10 articles (2003–2014) and included 23 patients with mean age of 1.5 years (0.5–18) at surgery. All patients were 46XY, n = 1 normal male karyotype with two cell lines. Explorative laparoscopy was performed in n = 2 and surgical management in n = 21. The 5-port technique was used in n = 10, 3-port in n = 9 and robot-assisted laparoscopic approach in n = 1 (n = 1 technique not described). Complete MDRs removal in n = 9, complete dissection and MDRs neck ligation with endoscopic loops in n = 11 and n = 1 uterus and cervix were split in the midline. After MDRs removal, there were n = 2 bilateral orchidopexy, n = 3 unilateral orchidopexy, n = 1 Fowler–Stephens stage-I and n = 1 orchiectomy. Mean operative time was 193 min (120–334), and there were no intraoperative complications. Mean follow-up was 20.5 months (3–54) and morbidity included 1 prostatic diverticula. There were 13 associations with hypospadias, of which 3 had mixed gonads and 3 bilateral cryptorchidism. Other associations were unilateral cryptorchidism and incarcerated inguinal hernia n = 1, right renal agenesis and left hydronephrosis n = 1 and n = 2 with transverse testicular ectopy.

Conclusion:

This MDRs analysis suggests that the laparoscopic approach is an effective and safe method of treatment as no intraoperative complication has reported, and there is low morbidity in the long-term follow-up.

Keywords: Müllerian duct remnants, laparoscopy techniques, outcomes, children

INTRODUCTION

Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome (PMDS) is a rare genetic disorder of internal male sexual development. These males have a 46XY karyotype with normal external male genitalia but with internal Müllerian duct structures, including a uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes and upper two-thirds of the vagina. It was first described by Nilson in 1939 and given the name hernia uteri inguinale, in literature, it is also named prostatic uticular cyst or ‘vagina masculinus’ in patients with other unregressed paramesonephric duct structures.[1,2,3]

PMDS is an autosomal recessive inherited disorder with failure of Müllerian duct regression, caused by a defect in either the genes coding for the anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) in 45% or the AMH receptor in 39%. No mutation for either the MIS gene or receptor can be found in 16% of patients. The indifferent phase of phenotypic sexual development ends at about 8 weeks of gestation, during which time, both the Müllerian and Wolffian ducts are present and positioned directly adjacent to one another sharing a common blood supply. In the male, the Müllerian ducts regress under the effect of AMH produced by the Sertoli cells of the testicles at about the 10th week of fetal life. Failure of regression of these structures occurs when AMH production is absent or flawed or when AMH is unable to effectively interact with its receptor on the target organ.[1,2,3,4,5,6]

After the first description of a laparoscopic approach for the management of Müllerian duct remnant (MDR) in an adult, in 1994 in the USA, the first laparoscopic treatment of MDR in the paediatric age group was reported in Europe in 1998.[7] Since then, a few cases have been reported about laparoscopy role in PMDR diagnosis and treatment. This study performed a literature review to determine feasibility and safety of laparoscopic management of MDRs.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Literature was searched for terms ‘Müllerian’ ‘duct’ ‘remnants’ and ‘laparoscopy'. Primary end points were age at surgery, laparoscopic technique, intraoperative complications and postoperative morbidity.

RESULTS

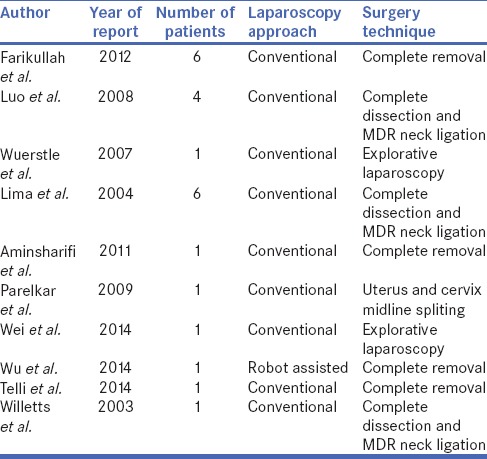

The search revealed 10 articles that met our inclusion criteria, published between 2003 and 2014 [Table 1]. Total number of patients was n = 23 with age distribution at surgery from 0.5 to 18 years and mean age of 1.5 years. All patients were 46XY, in n = 1, normal male karyotype with two cell lines was found. Regarding the use of laparoscopy in diagnosis and management of MDRs explorative laparoscopy was performed in n = 2 and surgical management in n = 21 patients.

Table 1.

Articles that met the inclusion criteria showing number of patients, laparoscopic approach and type of performed surgery

With regards to technical details of the procedures, the 5-port technique was used in n = 10, 3-port in n = 9 and robot-assisted laparoscopic approach in n = 1 (n = 1 technique not described) [Figure 1]. Both 0° and 30° scopes were used to visualise the lesions. In school-age children, 10-mm telescope and 10- and 5-mm instruments were used, whereas for smaller children, 5-mm telescope and 3-mm instruments were used. For robot-assisted laparoscopic approach, a 12-mm Patton Surgical robotic trocar was placed and two 8-mm robotic ports. The presence of cystoscope guiding light for MDRs management was used in n = 7. In patients where explorative laparoscopy was performed, open bilateral orchiopexy was performed at a later date in 1 patient and MDRs dissection and reconstruction by open surgery in another. A transperitoneal laparoscopy technique was used for in all MDRs surgeries.

Figure 1.

Laparoscopic management of Mullerrian duct remnants is approached with three different techniques

With regards to the operative techniques, complete MDRs removal was performed in n = 9, complete dissection and MDRs neck ligation with endoscopic loops or Hem-o-Lok clips in n = 11 and n = 1 uterus and cervix were split in the midline, and subdartos pouch was created and bilateral orchidopexy was performed [Figure 2]. After MDRs removal, there were n = 2 bilateral orchidopexy, n = 3 unilateral orchidopexy, n = 1 Fowler–Stephens stage-I and n = 1 orchiectomy. Mean surgery time was 193 min (120–334), and there were no intraoperative complications. Uterus and both fallopian tubes were found in n = 3 patients and complete uterus in n = 2.

Figure 2.

Laparoscopic management of Mullerrian duct remnants showing preferred surgical techniques

Mean follow-up was 20.5 months (3–54). A small prostatic diverticulum in one patients was reported after a 6 year follow-up, no other recurrent evidences or voiding dysfunctions were reported and no malignant alterations reported. In n = 13, MDRs were associated with hypospadias. Within this group, n = 3 had mixed gonads and n = 3 bilateral cryptorchidism. Other associations of MDR included unilateral cryptorchidism and incarcerated inguinal hernia n = 1, right renal agenesis and left hydronephrosis n = 1 and n = 2 with transverse testicular ectopy (TTE) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Association of Mullerrian duct remnants that were managed laparoscopically with concomitant anomalies

DISCUSSION

PMDS is characterised by the presence of the uterus, cervix, upper vagina and fallopian tubes in an otherwise normally differentiated 46, XY male. Reported incidence is 1%–4%. Hutson et al. classified PMDS into three groups: (1) Group A: the testes are in the position of the normal ovaries (female type); (2) Group B: one testis is found in a hernia sac or scrotum along with the uterus and tubes (male type) and (3) Group C: both testes are found in the same hernia sac with associated tubes and the uterus (male type).[8] MDR is associated with hypospadias or intersex disorders in 90% of cases, TTE in approximately 20% of the cases and bilateral cryptorchidism in about 10%.[2,4,9]

The most common presentation is a child with a normally appearing phallus and one scrotal and one inguinal testis. Up to 60% of patients with MDR remain asymptomatic although they can present with lower urinary tract inflammation and obstructive symptoms (including acute urinary retention) or recurrent cystitis, epididymitis, infertility and chronic pelvic or perineal pain.[2,7] Different open operative techniques are described, and there is agreement that orchidopexy is indicated to preserve spermatogenesis function and prevents testicular malignancy. There is no agreement however on the excision, partial removal or midline splitting of the MDR should be performed.[10]

MDRs may present with various signs and symptoms including urinary tract infection, pain and post-void incontinence, a palpable abdominal mass or recurrent epididymitis, but many of them are asymptomatic and they escape detection.[3,11,12] Therefore, MDR can be very challenging for diagnose. The diagnosis of children with disorders of sex development (DSD) requires a karyotype and different biochemical and radiological investigations in the context of a multidisciplinary team. Pelvic ultrasonography failed to identify Müllerian structures in 40% of patients with complex DSD. On the contrary, laparoscopy allowed excellent visualisation of pelvic structures and gonads in children with complex DSD.[13] An ultrasound scan may be helpful preoperatively to visualise any Müllerian remnants, but laparoscopy is the gold standard for diagnosis.[1] In recent decades, laparoscopy has been used for patients with PMDS for diagnosis or treatment; however, the information available in the literature is sporadic.[11,14] Optimal surgical management of PMDS has not been standardised, complete or partial removal of MDR or midline splitting and orchidopexy were reported. The main concern is that the retained Müllerian structure may become malignant.[14]

In this analysis, 87% of surgeons decided to remove the remnants. The incidence of malignant change in these testes is 5%–18%, which is the same as the rate of malignancy in abdominal testes in a man without PMDS. Assuming cancer occurrence is binomially distributed, we may formulate that we are 90% confident that between 3.1% and 8.4% of males with PMDS will develop a Müllerian malignancy.[1,9] In literature, three reported cases were found about the malignant alteration of MDRs. Theil et al. (2005) reported death of a 14-year-old boy with PMDS, due to metastasis of adenosarcoma arising from the Müllerian remnant.[15] Romero et al.[16] reported a 39-year-old man who developed adenocarcinoma of endocervical origin, arising from MDR, and Shinmura et al.[17] reported clear cell adenocarcinoma arising from the uterus in a 67-year-old man with PMDS.[18]

Although the mean follow-up was short in these studies, no malignancy has been reported. The major concern is to avoid possible injuries of vas deferens. The close anatomic association of Wolffian and Müllerian structures can make surgical management of PMDS challenging because care must be taken to avoid damaging the spermatic cord during hysterectomy and resection of the fallopian tubes.[10,11] There were no reported intraoperative injuries or complications in this study in all operative techniques. The presence of a cystoscope within the utricle orifice aids identification and safe dissection of the MDR, and it was used in 30% of patients in this meta-analysis.[12] Laparoscopic approach gives excellent visualisation and magnification which allows meticulous dissection of the mass from the pelvic organ, and manipulation of the pararectal and bladder neck region is minimal. This avoids injury to the pelvic nerves and thus helps preserve postoperative voiding and bowel function.[7] This is a huge benefit of laparoscopy as open surgical treatment of MDR in the male patient varies according to the size of the utricle, and a double approach often is necessary.[3] The use of laparoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of PMDS has been reported, and different surgical options and algorithms are suggested for management.[19,20] There is no agreement regarding the removal of the rudimentary Müllerian structures, and these procedures could be technically demanding, especially in small infants, but we can say that all described procedures are effective and safe to perform.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Farikullah J, Ehtisham S, Nappo S, Patel L, Hennayake S. Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome: Lessons learned from managing a series of eight patients over a 10-year period and review of literature regarding malignant risk from the Müllerian remnants. BJU Int. 2012;110(11 Pt C):E1084–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandli DW, Akbal C, Eugsster E, Hadad N, Havlik RJ, Kaefer M. Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome with bilateral abdominal testis: Surgical approach and review of the literature. J Pediatr Urol. 2005;1:423–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krstic ZD, Smoljanic Z, Micovic Z, Vukadinovic V, Sretenovic A, Varinac D. Surgical treatment of the Müllerian duct remnants. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:870–6. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.23958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo JH, Chen W, Sun JJ, Xie D, Mo JC, Zhou L, et al. Laparoscopic management of Müllerian duct remnants: Four case reports and review of the literature. J Androl. 2008;29:638–42. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.005496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wuerstle M, Lesser T, Hurwitz R, Applebaum H, Lee SL. Persistent mullerian duct syndrome and transverse testicular ectopia: Embryology, presentation, and management. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:2116–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lima M, Aquino A, Dòmini M, Ruggeri G, Libri M, Cimador M, et al. Laparoscopic removal of Müllerian duct remnants in boys. J Urol. 2004;171:364–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000102321.54818.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aminsharifi A, Afsar F, Pakbaz S. Laparoscopic management of Müllerian duct cysts in infants. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:1859–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutson JM, Chow CW, Ng WT. Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome with transverse testicular ectopia. Pediatr Surg Int. 1987;2:191–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Telli O, Gökçe MI, Haciyev P, Soygür T, Burgu B. Transverse testicular ectopia: A rare presentation with persistent Müllerian duct syndrome. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2014;6:180–2. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei CH, Wang NL, Ting WH, Du YC, Fu YW. Excision of Mullerian duct remnant for persistent Mullerian duct syndrome provides favorable short-and mid-term outcomes. J Pediatr Urol. 2014;10:929–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parelkar SV, Gupta RK, Oak S, Sanghvi B, Kaltari D, Patil RS, et al. Laparoscopic management of persistent Mullerian duct syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willetts IE, Roberts JP, MacKinnon AE. Laparoscopic excision of a prostatic utricle in a child. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003;19:557–8. doi: 10.1007/s00383-003-0993-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steven M, O'Toole S, Lam JP, MacKinlay GA, Cascio S. Laparoscopy versus ultrasonography for the evaluation of Mullerian structures in children with complex disorders of sex development. Pediatr Surg Int. 2012;28:1161–4. doi: 10.1007/s00383-012-3178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu JA, Hsieh MH. Robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy, gonadal biopsy, and orchiopexies in an infant with persistent Mullerian duct syndrome. Urology. 2014;83:915–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiel DD, Erhard MJ. Uterine adenosarcoma in a boy with persistent müllerian duct syndrome: first reported case. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:e29–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romero FR, Fucs M, Castro MG, Garcia CR, Fernandes Rde C, Perez MD. Adenocarcinoma of persistent Müllerian duct remnants: Case report and differential diagnosis. Urology. 2005;66:194–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shinmura Y, Yokoi T, Tsutsui Y. A case of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the Müllerian duct in persistent Müllerian duct syndrome: The first reported case. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1231–4. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200209000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manjunath BG, Shenoy VG, Raj P. Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome: How to deal with the Müllerian duct remnants - A review. Indian J Surg. 2010;72:16–9. doi: 10.1007/s12262-010-0003-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turaga KK, St Peter SD, Calkins CM, Holcomb GW 3rd, Ostlie DJ, Snyder CL. Hernia uterus inguinale: A proposed algorithm using the laparoscopic approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16:366–7. doi: 10.1097/01.sle.0000213722.49838.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiener JS, Jordan GH, Gonzales ET., Jr Laparoscopic management of persistent Müllerian duct remnants associated with an abdominal testis. J Endourol. 1997;11:357–9. doi: 10.1089/end.1997.11.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]