Abstract

Introduction:

Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) is widely used as a treatment option for gallbladder disease. However, obesity has been considered a relative contraindication to this approach due to more advanced technical difficulties. The aim of this report was to review our experience with SILC to evaluate the impact of body mass index (BMI) on the surgical outcome.

Patients and Methods:

Between May 2009 and February 2013, 237 patients underwent SILC at our institute. Pre- and post-operative data of the 17 obese patients (O-group) (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and 220 non-obese patients (NO-group) (BMI <29.9 kg/m2) were compared retrospectively. SILC was performed under general anaesthesia, using glove technique. Indications for surgery included benign gallbladder disease, except for emergent surgeries.

Results:

Mean age of patients was significantly higher in the NO-group than O-group (58.9 ± 13.5 years vs. 50.8 ± 14.0 years, P = 0.025). SILC was successfully completed in 233 patients (98.3%). Four patients (1.7%) in the NO-group required an additional port, and one patient was converted to an open procedure. The median operative time was 70 ± 25 min in the NO-group and 75.2 ± 18.3 min in the O-group. All complications were minor, except for one case in the NO-group that suffered with leakage of the cystic duct stump, for which endoscopic nasobiliary drainage was need.

Conclusion:

Our findings show that obesity, intended as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2, does not have an adverse impact on the technical difficulty and post-operative outcomes of SILC. Obesity-related comorbidities did not increase the risks for SILC.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, obesity, single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy

INTRODUCTION

Modifications of minimally invasive laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) have been achieved, including single-incision LC (SILC) and widely used as a treatment option for gallbladder disease.[1] On the other side, the patient's features such as body mass index (BMI), gender and age have been mentioned as potential affecting determinants for SILC.[2,3] In the current literature, the effects of high BMI on the results of the surgical therapy have not been sufficiently investigated after SILC, and the impact of obesity on the outcomes of SILC is still a controversial matter. The aim of this study was to review our experience with SILC to evaluate the impact of the BMI on the surgical outcome.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Data of pure single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomies (n = 237) from May 2009 to February 2013 were performed at our hospital by eight experienced surgeons in standard technique and collected into our surgical audit database.

Patients with symptomatic and/or benign gallbladder disease were included in this study, and all operations were performed. Exclusion criteria for single-incision surgery were patients with acute cholecystitis, diagnosed in computed tomography scan, with a history of gastrectomy and/or severe critical illness. The operations performed on known malignancies or as a part of other surgery were excluded from this study.

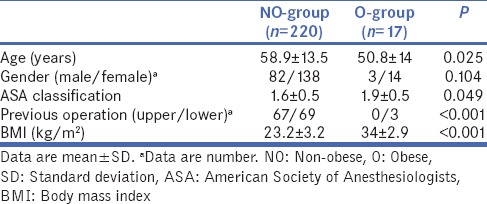

Age, gender, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification and BMI of the patients were also recorded [Table 1]. The results of operative data (operative time, blood loss, conversion rate, morbidity rate, diet resumption and post-operative hospital stay) were recorded [Table 2].

Table 1.

Patient's characteristics in the patient populations

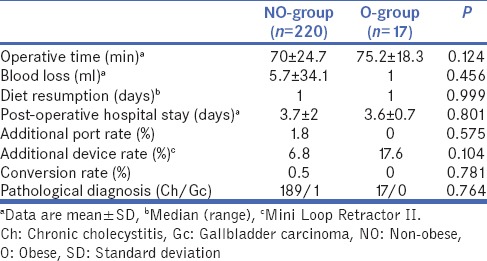

Table 2.

Operative details and clinical outcomes

Coronary heart disease was recorded based on history of hospital-verified myocardial infarction and/or chronic heart failure or a history of hospital-treated acute coronary syndrome or drug-imbursement for these conditions. History of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was obtained from medical records and mainly classified as having drug-imbursement for bronchial asthma or chronic bronchitis or daily need for medications for these disorders [Table 3].

Table 3.

Post-operative complications in both groups

Surgical technique

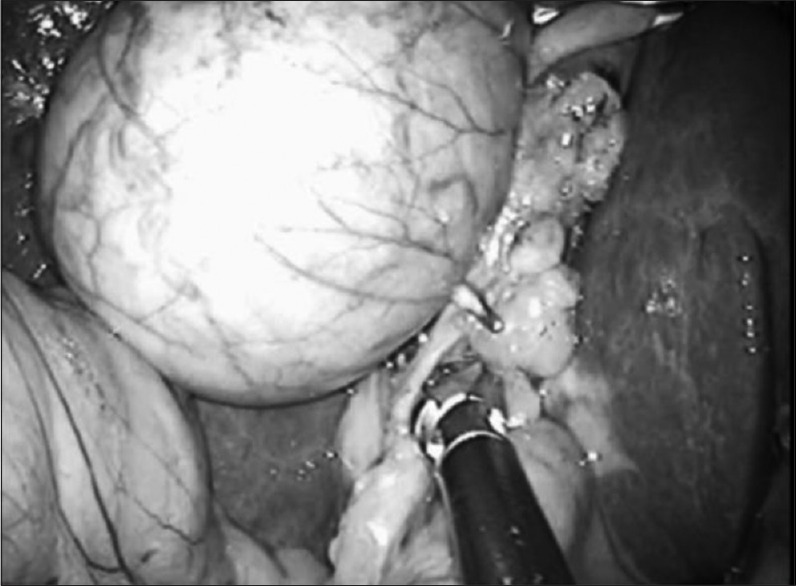

Under general anaesthesia, the patient was placed in the supine position with patient's legs apart and both arms are rolled. The surgeon stood between the patient's legs, the scopist stood on the left side of the patient and the scrub nurse stood on the right side of the patient. The video monitor was positioned near the right side of the head. The operation begins with a longitudinal incision direct through the umbilicus between both the umbilical edges at a length of 20 mm. After dissolving of eventually existing adhesions with the fingers, an Alexis wound retractor XS (Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA) and a 5.5-sized glove were used. Carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum (10 mmHg) was maintained throughout the procedure, and a 5 mm flexible laparoscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used for initial inspection of the abdominal cavity at a 20° reverse Trendelenburg, right-side-up position. We used as instruments conventional straight 5 mm bipolar forceps and Roticulator Endo Dissect™, being placed through the each finger of glove, called glove method (or glove technique). The Mini Loop Retractor™ (MLR) was punctured through the right hypochondrium in case of need. A special technique for a better movement inside the abdominal cavity is cross-handedness of the instruments that means to undercross the instrument in the right hand under the instrument in the left hand. For a right hander, the operation will be performed with the right hand. The left hand holds the gallbladder with a grasper [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The left hand holds the funds of the gallbladder with a grasper (Roticulator Endo Dissect™) and retracted through the right hypochondrium

First, the serosa of the dorsal and ventral sides of the gallbladder, including Calot's triangle, were dissected and the hilum was prepared with a bipolar forceps to expose the cystic duct and cystic artery [Figure 2]. Both structures were clipped with a 5 mm endoscopic clip applier (Endclip™ II ML 5 mm, Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) and divided with scissors. After dissection the gallbladder from the liver bed, the pneumoperitoneum was released and was removed through the Alexis wound retractor XS without a collecting bag [Figure 3]. The fascial incision was closed with a non-absorbable 0 suture (Prolene, Ethicon, Germany). Finally, skin closures were carried out by buried suture employing 4-0 nylon (Monocryl, Ethicon, Germany).

Figure 2.

The artery was dissected first and a critical view of the cystic duct was obtained

Figure 3.

Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed using glove technique through a 20 mm transumbilical incision

Statistical analysis

Univariate analyses for categorical variables were calculated with the χ2-test and for continuous variables with the Mann–Whitney U-test. The level of significance was considered as 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographic data

During the study, 237 patients underwent SILC. Of the 237 patients, 220 patients were in normal weight group (BMI <30 kg/m2) and 17 (7.2%) patients were in overweight group (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), of which 6 had Class II obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2). There was statistically significant difference in BMI between the NO-group and the O-group (23.2 ± 3.2 kg/m2 vs. 34 ± 2.9 kg/m2, P < 0.001). Mean age of patients was significantly higher in the NO-group than O-group (58.9 ± 13.5 years vs. 50.8 ± 14.0 years, P = 0.025). The median ASA class was 2 (range: 1–3) in the two groups. SILC was successfully completed in 233 patients (98.3%).

Both groups were difference significantly in terms of previous abdominal surgeries (NO-group vs. O-group; 61.8% vs. 17.6%, P < 0.001). Demographic and pre-operative characteristics of the patient are shown in Table 1.

Operative details and post-operative complications

There were no significant differences between two groups (i.e., NO-group vs. O-group) in operative time (70 ± 24.7 min vs. 75.2 ± 18.3 min), blood loss (5.7 ± 34.1 ml vs. 1.0 ml), conversion rate (0.5% vs. 0%) and morbidity rate (4.5% vs. 5.9%) in Tables 2 and 4.

Table 4.

Patient's comorbid conditions in both groups

The MLR and/or an additional 5 mm port were needed for several cases when required that were added fifteen patients in the NO-group and three patients in the O-group. There was no statistically significant difference in additional device rate between the NO-group and O-group (6.8% vs. 17.6%, P = 0.104). Four patients in the NO-group required additional port (one additional 5 mm trocar was placed right subcostally in the midclavicular region) because of the difficulty of laparoscopic dissection by chronic severe inflammation and adhesion to the omentum and the duodenum. Only four patients in the NO-group was need for conversion to the conventional LC by 4-trocar technique. Finally, conversion to open surgery for cholecystectomy was required in this one case of four (0.45%), because of severe cholecystitis, respectively. By contrast, neither conversion to open surgery nor the use of any additional port was required in the O-group [Table 2]. Finally, the completion rate of the pSILC was 91.1% at all (NO-group vs. O-group; 91.8% vs. 82.4%, P = 0.777).

Diet resumption was 1 day (median) in the both groups, and length of post-operative hospital stay was 3 days (median) in the both groups can be seen in Table 2 (P = 0.801). Due to wound infection, wound drainage was undertaken in one patient (Clavien Grade I), and one patient in the NO-group that suffered with leakage of the cystic duct stump, for which endoscopic nasobiliary drainage was need. None of patients underwent a second operation. There was no peri- or post-operative mortality in the both groups. Only one case (0.4%) in the O-group experienced port site hernia (PSH) and no patient in the NO-group [Table 3].

Pathology

All specimens were analysed by experienced pathologists in our institution. In NO-group, signs of chronic cholecystic inflammation were diagnosed in 192 patients (87.3%), and 27 (12.3%) patients had polyps or tumours (i.e., adenomyoma or adenoma). Only one patient (0.4%) in the NO-group revealed gallbladder carcinoma in the membrane [Table 2].

DISCUSSION

Today, the laparoscopic approach is the gold standard in the treatment of gallstone disease. Although SILC is not as revolutionary a concept as the initial forays into laparoscopy, it is still beset with numerous concerns with regard to a longer operating time and a feeling of disbelief regarding its potential advantages. It is important that new surgical techniques are supported by strong evidence to demonstrate their benefits to the patient, to say nothing of the lower SILC rates for obese patients.

Obesity is one predisposing factor for cholelithiasis and cholecystitis.[4,5] Moreover, obesity is associated with increased cardiopulmonary disease, and anaesthetic complications during surgery on obese patients have increased.[6,7] This is why obesity has been considered to be a relative contraindication to SILC, due to more advanced technical difficulties.[8] Our study provides preliminary indications that there is a comparable post-operative outcome for obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and non-obese patients undergoing SILC for benign gallbladder disease.

Patient's demographic characteristics have been discussed in the literature as potential outcome determinants after SILC, and two large reviews commented on the impact of the patient BMI.[2,9] A review by Antoniou et al.[2] including 1166 patients, uncovered a longer duration of operation for the included studies with a mean patient BMI >30 kg/m2. However, as the complications and success rates were not negatively influenced by a higher BMI, the exclusion of obese patients from SPC (single-port cholecystectomy) was considered to be inappropriate. Comparable to these findings, Allemann et al.[9] concluded that ‘a high BMI is not a limiting factor or contraindication’ for single-port access surgery. The literature documents the safety and feasibility of single-incision laparoscopic surgery, even in bariatric patients.[10]

Overall, obese and non-obese patients did not differ in terms of the post-operative complication rates or the severity of the observed complications. Accordingly, the length of the post-operative hospital stay was comparable for the NO-group and O-group (3.7 ± 2 days vs. 3.6 ± 0.7 days, P = 0.801) [Table 2]. These observations are worth mentioning as many surgeons still adopt a cautious approach towards single-port surgery in obese patients. Obesity is not a contraindication to safe SILC, but it is associated with an increased need for adhesiolysis and a longer operative time. In the hands of an experienced surgical team, SILC is the therapeutic procedure of choice for gallstone disease in patients with obesity.

On the other hand, after an open laparotomy by an intraumbilical vertical skin incision, the need for the insertion of an additional device (i.e., MLR) is due to technical difficulty, with a failure to adequately expose the Calot's triangle, secondary to extensive adhesions, because of severe inflammation. The insertion of the 5 mm port is the same as in the reasons mentioned above after adding the MLR. Finally, one converts to the open surgery for cholecystectomy if one is unable to overcome the operative difficulty after the insertion of the port.

We define SILC as not adding any additional devices (i.e., MLR or 5 mm port). In all, the need for the insertion of an MLR was revealed in 18 patients (7.6%) and the case of an added port was in four patients (1.7%). Neither conversion to open surgery nor the use of any additional ports was required in the O-group. Finally, the completion rate of the pSILC was 91.1% (NO-group vs. O-group; 91.8% vs. 82.4%, P = 0.777).

Significant independent predictive factors for conversion include acute cholecystitis, increasing age, male, gallbladder wall thickness and obesity.[11,12,13] In our study, obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) was associated with trends towards an increased additional device, but not an increased conversion rate; the reason for conversion is severe inflammation due to chronic cholecystitis in the NO-group. Whether there is a need to convert to the open surgery or not, the compulsory factor is the degree of inflammation, not the BMI.

Complications occurred in 11 of the 237 patients (4.6%), which were minor (Clavien Grade I) and related to surgery, except for one case in the NO-group that suffered leakage of the cystic duct stump, for which endoscopic nasobiliary drainage was required. The patient improved rapidly with no complaints. After taking another look at the operative video, we determined that the chronic inflammation of the gallbladder was not very great. The bile duct damage caused by forceps and clip's displacement weren't seen.

No significant difference was found in the morbidity rates between the NO-group and the O-group (4.5% vs. 5.9%; P = 0.801), i.e., post-operative bleeding (P = 0.781), wound seroma (P = 0.49), wound infection (P = 0.781) or bile leakage (P = 0.781). There was no decrease in the morbidity rate following an improvement in technical skills although it was lower in our series than in the other reports.

The recently published meta-analyses by Trastulli et al. compared single-incision and conventional LC. The SILC approach had a higher procedure failure rate than the LC approach, required a longer operating time and was associated with greater intraoperative blood loss. However, there were no differences between the two approaches in the rate of conversion to open surgery, length of hospital stay, post-operative pain, adverse events or wound infections.[14]

In the post-operative PSH rate, no significant differences were found between the SILC approach and the conventional laparoscopic approach. The reported PSH incidence after SILC varied from 0.09% to 5.8%,[2,15] but the follow-up times were short. Moreover, several studies did not report on the technique and material used for closure.[14,16,17,18]

Up until now, few studies evaluating the BMI for SILC have been reported in the literature. Reibetanz et al.[19] compared overweight (17 patients) and normal weight (83 patients) patients in SILCs. They observed post-operative complications in 10 (10%) of the patients. The majority of these complications were mild wound complications and subcutaneous hematomas. One of the 17 overweight patients (5.8%) experienced asymptomatic PSH 4 months after surgery. Post-operative wound infections occur in as many as 15% of morbidly obese patients, and late incisional hernias occur in up to 20% of these patients.[20,21,22] Conversely, Yilmaz et al. reported post-operative complications in 31 (15.3%) patients. The majority of these complications were mild wound complications in 18 (8.9%) patients, total. They also reported that PSHs in 11 (5.4%) patients were not correlated to the BMI.[3] In our study, only one patient experienced PSH (0.4%) in the O-group. In our case, this occurred 18 months after surgery and the individual was observed as an outpatient because there was no indication for operation. Furthermore, one must always pay attention that the fascia is closed with sutures to reduce the risk of developing a PSH.

In the case of pSILC, studies, so far, have demonstrated that it is a safe and feasible method of surgery. Further clinical trials are now needed to demonstrate the additional advantages of this attractive technique.

CONCLUSION

In contrast with some previously reported series of SILC, our findings show that obesity, intended as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2, does not have an adverse impact on the technical difficulty and post-operative outcomes of SILC, except for severe inflammation in cholecystitis or severe adhesions after another upper abdominal surgery. Obesity-related comorbidities did not increase the risks for SILC.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee PC, Lo C, Lai PS, Chang JJ, Huang SJ, Lin MT, et al. Randomized clinical trial of single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus minilaparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1007–12. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoniou SA, Pointner R, Granderath FA. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:367–77. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yilmaz H, Alptekin H, Acar F, Calisir A, Sahin M. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy and overweight patients. Obes Surg. 2014;24:123–7. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1723–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afdhal NH. Diseases of the gallbladder and bile ducts. In: Goldman L, Ausiello D, editors. Cecil Textbook of Medicine. 22nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004. pp. 949–56. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eichenberger A, Proietti S, Wicky S, Frascarolo P, Suter M, Spahn DR, et al. Morbid obesity and postoperative pulmonary atelectasis: An underestimated problem. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:1788–92. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200212000-00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hussien M, Appadurai IR, Delicata RJ, Carey PD. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the grossly obese: 4 years experience and review of literature. HPB (Oxford) 2002;4:157–61. doi: 10.1080/13651820260503792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khambaty F, Brody F, Vaziri K, Edwards C. Laparoscopic versus single-incision cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2011;35:967–72. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-0998-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allemann P, Schafer M, Demartines N. Critical appraisal of single port access cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1476–80. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saber AA, El-Ghazaly TH. Early experience with SILS port laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:428–30. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181c48993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibrahim S, Hean TK, Ho LS, Ravintharan T, Chye TN, Chee CH. Risk factors for conversion to open surgery in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2006;30:1698–704. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0612-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavlidis TE, Marakis GN, Ballas K, Symeonidis N, Psarras K, Rafailidis S, et al. Risk factors influencing conversion of laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:414–8. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipman JM, Claridge JA, Haridas M, Martin MD, Yao DC, Grimes KL, et al. Preoperative findings predict conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy. Surgery. 2007;142:556–63. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trastulli S, Cirocchi R, Desiderio J, Guarino S, Santoro A, Parisi A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing single-incision versus conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2013;100:191–208. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alptekin H, Yilmaz H, Acar F, Kafali ME, Sahin M. Incisional hernia rate may increase after single-port cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:731–7. doi: 10.1089/lap.2012.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma J, Cassera MA, Spaun GO, Hammill CW, Hansen PD, Aliabadi-Wahle S. Randomized controlled trial comparing single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy and four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 2011;254:22–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182192f89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai EC, Yang GP, Tang CN, Yih PC, Chan OC, Li MK. Prospective randomized comparative study of single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus conventional four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2011;202:254–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips MS, Marks JM, Roberts K, Tacchino R, Onders R, DeNoto G, et al. Intermediate results of a prospective randomized controlled trial of traditional four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1296–303. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-2028-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reibetanz J, Germer CT, Krajinovic K. Single-port cholecystectomy in obese patients: Our experience and a review of the literature. Surg Today. 2013;43:255–9. doi: 10.1007/s00595-012-0238-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kellum JM, DeMaria EJ, Sugerman HJ. The surgical treatment of morbid obesity. Curr Probl Surg. 1998;35:791–858. doi: 10.1016/s0011-3840(98)80009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG, Long SB, Morris PG, Brown BM, et al. Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 1995;222:339–50. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199509000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh CH, Kim HJ, Oh S. Weight loss following transected gastric bypass with proximal Roux-en-Y. Obes Surg. 1997;7:142–7. doi: 10.1381/096089297765556042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]