Abstract

In a real uniformly convex and uniformly smooth Banach space, some new monotone projection iterative algorithms for countable maximal monotone mappings and countable weakly relatively non-expansive mappings are presented. Under mild assumptions, some strong convergence theorems are obtained. Compared to corresponding previous work, a new projection set involves projection instead of generalized projection, which needs calculating a Lyapunov functional. This may reduce the computational labor theoretically. Meanwhile, a new technique for finding the limit of the iterative sequence is employed by examining the relationship between the monotone projection sets and their projections. To check the effectiveness of the new iterative algorithms, a specific iterative formula for a special example is proved and its computational experiment is conducted by codes of Visual Basic Six. Finally, the application of the new algorithms to a minimization problem is exemplified.

Keywords: Maximal monotone mapping, Weakly relatively non-expansive mapping, Projection, Limit of a sequence of sets, Uniformly convex and uniformly smooth Banach space

Introduction and preliminaries

Let E be a real Banach space with its dual space. Suppose that C is a nonempty closed and convex subset of E. The symbol 〈⋅, ⋅〉 denotes the generalized duality pairing between E and . The symbols “→” and “⇀” denote strong and weak convergence either in E or in , respectively.

A Banach space E is said to be strictly convex [1] if for which are linearly independent,

The above inequality is equivalent to the following:

A Banach space E is said to be uniformly convex [1] if for any two sequences and in E such that and , holds.

If E is uniformly convex, then it is strictly convex.

The function is called the modulus of smoothness of E [2] if it is defined as follows:

A Banach space E is said to be uniformly smooth [2] if , as .

The Banach space E is uniformly smooth if and only if is uniformly convex [2].

We say E has Property (H) if for every sequence which converges weakly to and satisfies as necessarily converges to x in the norm.

If E is uniformly convex and uniformly smooth, then E has Property (H).

With each , we associate the set

Then the multi-valued mapping is called the normalized duality mapping [1]. Now, we list some elementary properties of J.

Lemma 1.1

If E is a real reflexive and smooth Banach space, then J is single valued;

if E is reflexive, then J is surjective;

if E is uniformly smooth and uniformly convex, then is also the normalized duality mapping from into E. Moreover, both J and are uniformly continuous on each bounded subset of E or , respectively;

for and , .

For a nonlinear mapping U, we use and to denote its fixed point set and null point set, respectively; that is, and .

Definition 1.2

([3])

A mapping is said to be monotone if, for , , we have . The monotone mapping T is called maximal monotone if for .

Definition 1.3

([4])

The Lyapunov functional is defined as follows:

Definition 1.4

([5])

Let be a mapping, then

an element is said to be an asymptotic fixed point of B if there exists a sequence in C which converges weakly to p such that , as . The set of asymptotic fixed points of B is denoted by ;

is said to be strongly relatively non-expansive if and for and ;

an element is said to be a strong asymptotic fixed point of B if there exists a sequence in C which converges strongly to p such that , as . The set of strong asymptotic fixed points of B is denoted by ;

is said to be weakly relatively non-expansive if and for and .

Remark 1.5

It is easy to see that strongly relatively non-expansive mappings are weakly relatively non-expansive mappings. However, an example in [6] shows that a weakly relatively non-expansive mapping is not a strongly relatively non-expansive mapping.

Lemma 1.6

([5])

Let E be a uniformly convex and uniformly smooth Banach space and C be a nonempty closed and convex subset of E. If is weakly relatively non-expansive, then is a closed and convex subset of E.

Lemma 1.7

([3])

Let be maximal monotone, then

is a closed and convex subset of E;

if and with , or and with , then and .

Definition 1.8

([4])

If E is a reflexive and strictly convex Banach space and C is a nonempty closed and convex subset of E, then for each there exists a unique element such that . Such an element v is denoted by and is called the metric projection of E onto C.

Let E be a real reflexive, strictly convex, and smooth Banach space and C be a nonempty closed and convex subset of E, then for , there exists a unique element satisfying . In this case, , define by , and then is called the generalized projection from E onto C.

It is easy to see that is coincident with in a Hilbert space.

Maximal monotone mappings and weakly or strongly relatively non-expansive mappings are different types of important nonlinear mappings due to their practical background. Much work has been done in designing iterative algorithms either to approximate a null point of maximal monotone mappings or a fixed point of weakly or strongly relatively non-expansive mappings, see [5–10] and the references therein. It is a natural idea to construct iterative algorithms to approximate common solutions of a null point of maximal monotone mappings and a fixed point of weakly or strongly relatively non-expansive mappings, which can be seen in [11–15] and the references therein. Now, we list some closely related work.

In [12], Wei et al. presented the following iterative algorithms to approximate a common element of the set of null points of the maximal monotone mapping and the set of fixed points of the strongly relatively non-expansive mapping , where E is a real uniformly convex and uniformly smooth Banach space:

| 1.1 |

| 1.2 |

and

| 1.3 |

Under some mild assumptions, generated by (1.1), (1.2), or (1.3) is proved to be strongly convergent to . Compared to projective iterative algorithms (1.1) and (1.2), iterative algorithm (1.3) is called monotone projection method since the projection sets , , and are all monotone in the sense that , , and for . Theoretically, the monotone projection method will reduce the computation task.

In [13], Klin-eam et al. presented the following iterative algorithm to approximate a common element of the set of null points of the maximal monotone mapping and the sets of fixed points of two strongly relatively non-expansive mappings , where C is the nonempty closed and convex subset of a real uniformly convex and uniformly smooth Banach space E.

| 1.4 |

Under some assumptions, generated by (1.4) is proved to be strongly convergent to .

In [14], Wei et al. extended the topic to the case of finite maximal monotone mappings and finite strongly relatively non-expansive mappings . They constructed the following two iterative algorithms in a real uniformly convex and uniformly smooth Banach space E:

| 1.5 |

and

| 1.6 |

Under some assumptions, generated by (1.5) or (1.6) is proved to be weakly convergent to .

Inspired by the previous work, in Sect. 2.1, we shall construct some new iterative algorithms to approximate the common element of the sets of null points of countable maximal monotone mappings and the sets of fixed points of countable weakly relatively non-expansive mappings. New proof techniques can be found, restrictions are mild, and error is considered. In Sect. 2.2, an example is listed and a specific iterative formula is proved. Computational experiments which show the effectiveness of the new abstract iterative algorithms are conducted. In Sect. 2.3, an application to the minimization problem is demonstrated.

The following preliminaries are also needed in our paper.

Definition 1.9

([16])

Let be a sequence of nonempty closed and convex subsets of E, then

, which is called strong lower limit, is defined as the set of all such that there exists for almost all n and it tends to x as in the norm.

, which is called weak upper limit, is defined as the set of all such that there exists a subsequence of and for every and it tends to x as in the weak topology;

if , then the common value is denoted by .

Lemma 1.10

([16])

Let be a decreasing sequence of closed and convex subsets of E, i.e., if . Then converges in E and .

Lemma 1.11

([17])

Suppose that E is a real reflexive and strictly convex Banach space. If exists and is not empty, then converges weakly to for every . Moreover, if E has Property (H), the convergence is in norm.

Lemma 1.12

([18])

Let E be a real smooth and uniformly convex Banach space, and let and be two sequences of E. If either or is bounded and , as , then , as .

Lemma 1.13

([19])

Let E be a real uniformly convex Banach space and . Then there exists a continuous, strictly increasing, and convex function with such that

for with and .

Strong convergence theorems and experiments

Strong convergence for infinite maximal monotone mappings and infinite weakly relatively non-expansive mappings

In this section, we suppose that the following conditions are satisfied:

E is a real uniformly convex and uniformly smooth Banach space and is the normalized duality mapping;

is maximal monotone and is weakly relatively non-expansive for each ;

and are two real number sequences in () for . is a real number sequence in () for ;

is the error sequence in E.

Algorithm 2.1

Step 1. Choose . Let for . and . Set , and go to Step 2.

Step 2. Compute and for . If and for all , then stop; otherwise, go to Step 3.

Step 3. Construct the sets , , and as follows:

and

go to Step 4.

Step 4. Choose any element for .

Step 5. Set , and return to Step 2.

Theorem 2.1

If, in Algorithm 2.1, and for all , then .

Proof

Since , then from Step 2 in Algorithm 2.1, we know that for all , which implies that for . Therefore, .

Since , then in view of Lemma 1.1 for . Thus , .

This completes the proof. □

Theorem 2.2

Suppose for , , , and , as . Then the iterative sequence , as .

Proof

We split the proof into eight steps.

Step 1. is a nonempty subset of E.

In fact, we shall prove that , which ensures that .

For this, we shall use inductive method. Now, .

If , it is obvious that . Since is monotone, then

Thus , which ensures that .

Suppose the result is true for . Then, if , we have

Then , which ensures that .

Therefore, by induction, for .

Step 2. is a nonempty closed and convex subset of E for .

Since is equivalent to , then it is easy to see that is closed and convex for . Thus is closed and convex for .

Next, we shall use inductive method to show that for , which ensures that for .

In fact, .

If , it is obvious that . Then, from the definition of weakly relatively non-expansive mappings, we have

Combining this with Step 1, we know that for . Therefore, .

Suppose the result is true for . Then, if , we know from Step 1 that for . Moreover,

which implies that , and then . Therefore, by induction,

Step 3. Set . Then , as .

From the construction of in Step 3 of Algorithm 2.1, for . Lemma 1.10 implies that exists and . Since E has Property (H), then Lemma 1.11 implies that , as .

Step 4. is well defined.

It suffices to show that . From the definitions of and infimum, we know that for there exists such that

This ensures that for .

Step 5. as .

Since , then in view of Lemma 1.13 and the fact that is convex, we have, for ,

Therefore,

Letting , then as . Since , then , as .

Step 6. for , as .

Since , then

Thus, by using Step 5 and by letting , we have

as . Using Lemma 1.12, for , as . Since , then for , as . Since , then for , as .

Step 7. for , as .

Since , then noticing Steps 5 and 6,

as . Lemma 1.12 implies that , as . Since , then for , as .

Step 8. .

Since , then . Since , , and , then for , as . Using Lemma 1.7, .

Since , then in view of Lemma 1.1, , as . Lemma 1.6 implies that .

This completes the proof. □

Corollary 2.3

If , denote by T the maximal monotone mapping and by S the weakly relatively non-expansive mapping, then Algorithm 2.1 reduces to the following:

where , , , and . Then

Algorithm 2.2

Only doing the following changes in Algorithm 2.1, we get Algorithm 2.2:

and

Theorem 2.4

If, in Algorithm 2.2, and for all , then .

Proof

Similar to Theorem 2.1, the result follows. □

Theorem 2.5

We only change the condition that in Theorem 2.2 by , as . Then the iterative sequence , as .

Proof

Copy Steps 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6 in Theorem 2.2 and make slight changes in the following steps.

Step 2. is a nonempty closed and convex subset of E for .

Since is equivalent to , then it is easy to see that is closed and convex for . Thus is closed and convex for .

Next, we shall use inductive method to show that for , which ensures that for .

In fact, .

If , it is obvious that . Then, from the definition of weakly relatively non-expansive mappings, we have

Combining this with Step 1, we know that for . Therefore, .

Suppose the result is true for . Then, if , we know from Step 1 that for . Moreover,

which implies that and then . Therefore, by induction, for .

Step 7. for , as .

Since , then in view of the facts that and Step 6,

as , for . Lemma 1.12 implies that for , as .

Step 8. .

In the same way as Step 8 in Theorem 2.2, we have . Since , then , as . Thus in view of Lemma 1.6, .

This completes the proof. □

Corollary 2.6

If , denote by T the maximal monotone mapping and by S the weakly relatively non-expansive mapping, then Algorithm 2.2 reduces to the following:

where , , and . Then

Remark 2.7

Compared to the existing related work, e.g., [12–14], strongly relatively non-expansive mappings are extended to weakly relatively non-expansive mappings. Moreover, in our paper, the discussion on this topic is extended to the case of infinite maximal monotone mappings and infinite weakly relatively non-expansive mappings.

Remark 2.8

Calculating the generalized projection in [12] or in [13] is replaced by calculating the projection in Step 3 in our Algorithms 2.1 and 2.2, which makes the computation easier.

Remark 2.9

A new proof technique for finding the limit is employed in our paper by examining the properties of the projective sets sufficiently, which is quite different from that for finding the limit in [12] or in [13].

Remark 2.10

Theoretically, the projection is easier for calculating than the generalized projection in a general Banach space since the generalized projection involves a Lyapunov functional. In this sense, iterative algorithms constructed in our paper are new and more efficient.

Special cases in Hilbert spaces and computational experiments

Corollary 2.11

If E reduces to a Hilbert space H, then iterative Algorithm 2.1 becomes the following one:

| 2.1 |

The results of Theorems 2.1 and 2.2 are true for this special case.

Corollary 2.12

If E reduces to a Hilbert space H, then iterative Algorithm 2.2 becomes the following one:

| 2.2 |

The results of Theorems 2.4 and 2.5 are true for this special case.

Corollary 2.13

If, further , then (2.1) and (2.2) reduce to the following two cases:

| 2.3 |

and

| 2.4 |

The results of Corollaries 2.3 and 2.6 are true for the special cases, respectively.

Remark 2.14

Take , , and for . Let and for . Then T is maximal monotone and S is weakly relatively non-expansive. Moreover, .

Remark 2.15

Taking the example in Remark 2.14 and choosing the initial value , we can get an iterative sequence by algorithm (2.3) in the following way:

| 2.5 |

where , . Moreover, , as .

Proof

We can easily see from iterative algorithm (2.3) that

| 2.6 |

and

| 2.7 |

To analyze the construction of set , we notice that is equivalent to

| 2.8 |

In view of (2.7), compute the left-hand side of (2.8):

| 2.9 |

Meanwhile, compute the right-hand side of (2.8):

| 2.10 |

| 2.11 |

Next, we shall use inductive method to show that

| 2.12 |

In fact, if , then , thus . From (2.11), . And then . So we have

Therefore, we may choose as follows:

From (2.6), . Then . And it is easy to see . Thus (2.12) is true for .

Suppose (2.12) is true for , that is,

Then, for , we first analyze the set .

Note that , then is equivalent to . Then

From (2.11),

Now, we analyze set .

Since , then . Thus is equivalent to .

It is easy to check that , and .

Thus . Then we may choose such that

Now, we show that .

Since

then

which is obviously true. Thus .

Next, we show that .

Since , then

| 2.13 |

Note that

then (2.13) is true, which implies that .

Finally, we show that .

From the definition of , we have . Then . Since , then , which implies that .

Therefore, by induction, (2.12) is true for . Since , then exists. Set . From (2.12), and from (2.6), . Then in view of (2.7), . That is, .

This completes the proof. □

Remark 2.16

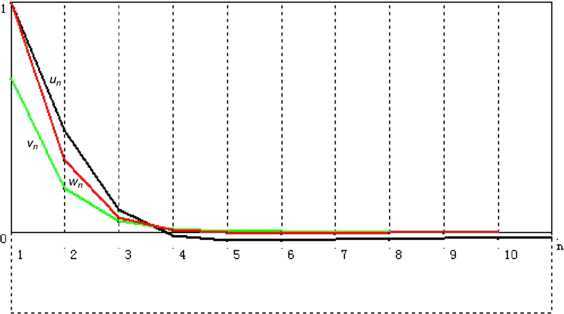

We next do a computational experiment on (2.5) in Remark 2.15 to check the effectiveness of iterative algorithm (2.3). By using the codes of Visual Basic Six, we get Table 1 and Fig. 1, from which we can see the convergence of , , and .

Table 1.

Numerical results of , , and with initial

| n | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.666666666666667 | 1.00000000000000 | 1.00000000000000 |

| 2 | 0.188493070669609 | 0.315479212008828 | 0.442465353348047 |

| 3 | 0.047734978022387 | 0.063917141637640 | 0.096281468868147 |

| 4 | 0.013887781581545 | 0.006938907907725 | −0.01390771311373 |

| 5 | 0.005016751133393 | −0.00287604161289 | −0.03444721259803 |

| 6 | 0.002022073632571 | −0.00418691873111 | −0.03523188054954 |

| 7 | 0.000854971429905 | −0.00391942854572 | −0.03256582839944 |

| 8 | 0.000371596957448 | −0.00362300404227 | −0.02949958193595 |

| 9 | 0.000164574841194 | −0.00281862431655 | −0.02668421757849 |

| 10 | 0.000073908605586 | −0.002357850182411 | −0.02424367927438 |

Figure 1.

Convergence of , , and

Remark 2.17

Similar to Remark 2.15, considering the same example in Remark 2.14 and choosing the initial value , we can get an iterative sequence by algorithm (2.4) in the following way:

| 2.14 |

where and for . Then , , and converge strongly to , as .

Remark 2.18

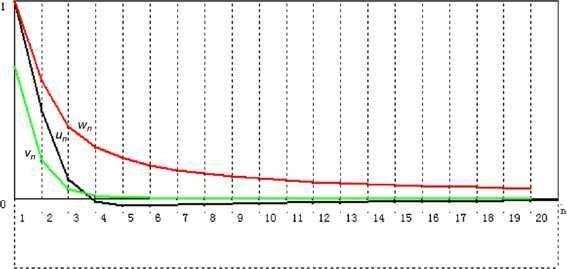

We do a computational experiment on (2.14) in Remark 2.17 to check the effectiveness of iterative algorithm (2.4). By using the codes of Visual Basic Six, we get Table 2 and Fig. 2, from which we can see the convergence of , , and .

Table 2.

Numerical esults of , , and with initial

| n | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.666666666666667 | 1.00000000000000 | 1.00000000000000 |

| 2 | 0.188493070669609 | 0.594246535334805 | 0.442465353348047 |

| 3 | 0.047734978022387 | 0.365156652014924 | 0.096281468868147 |

| 4 | 0.013887781581545 | 0.260415836186159 | −0.01390771311373 |

| 5 | 0.005016751133393 | 0.204013400906715 | −0.03444721259803 |

| 6 | 0.002022073632571 | 0.168351728027143 | −0.03523188054954 |

| 7 | 0.000854971429905 | 0.143589975511347 | −0.03256582839944 |

| 8 | 0.000371596957448 | 0.125325147337767 | −0.02949958193595 |

| 9 | 0.000164574841194 | 0.111257399858839 | −0.02668421757849 |

| 10 | 0.000073908605586 | 0.100066517745027 | −0.02424367927438 |

| 11 | 0.000033552200238 | 0.090939592909307 | −0.02216063262202 |

| 12 | 0.000015364834636 | 0.083347417765083 | −0.02038360583157 |

| 13 | 0.000007086981657 | 0.076929618752290 | −0.01885943628695 |

| 14 | 0.000003288762206 | 0.071431625279192 | −0.01754220267938 |

| 15 | 0.000001534136645 | 0.066668098527535 | −0.01639454294823 |

| 16 | 0.000000718881060 | 0.062500673950994 | −0.01538669196834 |

| 17 | 0.000000338196904 | 0.058823847714733 | −0.01449504667360 |

| 18 | 0.000000159662486 | 0.055555706347903 | −0.01370083322728 |

| 19 | 0.000000075612039 | 0.052631650579827 | −0.01298901840146 |

| 20 | 0.000000035908223 | 0.050000034112812 | −0.01234746359706 |

Figure 2.

Convergence of , , and

Applications to minimization problems

Let be a proper convex, lower-semicontinuous function. The subdifferential ∂h of h is defined as follows: ,

Theorem 2.19

Let E, S, , , , and be the same as those in Corollary 2.3. Let be a proper convex, lower-semicontinuous function. Let be generated by

Then

if and for all , then .

If and , then the iterative sequence , as .

Proof

Similar to [11], is equivalent to . Then . So, Corollary 2.3 ensures the desired results.

This completes the proof. □

Theorem 2.20

We only do the following changes in Theorem 2.19: and . Then, under the assumptions of Corollary 2.6, we still have the result of Theorem 2.19.

Acknowledgements

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11071053), Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (A2014207010), Key Project of Science and Research of Hebei Educational Department (ZD2016024), Key Project of Science and Research of Hebei University of Economics and Business (2016KYZ07), Youth Project of Science and Research of Hebei University of Economics and Business (2017KYQ09) and Youth Project of Science and Research of Hebei Educational Department (QN2017328).

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Li Wei, Email: diandianba@yahoo.com.

Ravi P. Agarwal, Email: ravi.agarwal@tamuk.edu

References

- 1.Takahashi W. Nonlinear Functional Analysis. Fixed Point Theory and Its Applications. Yokohama: Yokohama Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal R.P., O’Regan D., Sahu D.R. Fixed Point Theory for Lipschitz-Type Mappings with Applications. Berlin: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pascali D., Sburlan S. Nonlinear Mappings and Monotone Type. The Netherlands: Sijthoff and Noordhoff; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alber Y.I. Metric and generalized projection operators in Banach spaces: properties and applications. In: Kartsatos A.G., editor. Theory and Applications of Nonlinear Operators of Accretive and Monotone Type. New York: Dekker; 1996. pp. 15–50. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J.L., Su Y.F., Cheng Q.Q. Simple projection algorithm for a countable family of weak relatively nonexpansive mappings and applications. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2012;2012:205. doi: 10.1186/1687-1812-2012-205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J.L., Su Y.F., Cheng Q.Q. Hybrid algorithm of fixed point for weak relatively nonexpansive multivalued mappings and applications. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2012;2012:479438. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsushita S., Takahashi W. A strong convergence theorem for relatively nonexpansive mappings in a Banach space. J. Approx. Theory. 2005;134:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jat.2005.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y. Weak convergence of a hybrid type method with errors for a maximal monotone mapping in Banach spaces. J. Inequal. Appl. 2015;2015:260. doi: 10.1186/s13660-015-0772-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su Y.F., Li M.Q., Zhang H. New monotone hybrid algorithm for hemi-relatively nonexpansive mappings and maximal monotone operators. Appl. Math. Comput. 2011;217:5458–5465. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei L., Tan R. Iterative schemes for finite families of maximal monotone operators based on resolvents. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2014;2014:451279. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei L., Cho Y.J. Iterative schemes for zero points of maximal monotone operators and fixed points of nonexpansive mappings and their applications. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2008;2008:168468. doi: 10.1155/2008/168468. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei L., Su Y.F., Zhou H.Y. Iterative convergence theorems for maximal monotone operators and relatively nonexpansive mappings. Appl. Math. J. Chin. Univ. Ser. B. 2008;23(3):319–325. doi: 10.1007/s11766-008-1951-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klin-eam C., Suantai S., Takahashi W. Strong convergence of generalized projection algorithms for nonlinear operators. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2009;2009:649831. doi: 10.1155/2009/649831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei L., Su Y.F., Zhou H.Y. Iterative schemes for strongly relatively nonexpansive mappings and maximal monotone operators. Appl. Math. J. Chin. Univ. Ser. B. 2010;25(2):199–208. doi: 10.1007/s11766-010-2195-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue G., Takahashi W., Zembayashi K. Strong convergence theorems by hybrid methods for maximal monotone operator and relatively nonexpansive mappings in Banach spaces. J. Convex Anal. 2009;16(16):791–806. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosco U. Convergence of convex sets and of solutions of variational inequalities. Adv. Math. 1969;3(4):510–585. doi: 10.1016/0001-8708(69)90009-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsukada M. Convergence of best approximations in a smooth Banach space. J. Approx. Theory. 1984;40:301–309. doi: 10.1016/0021-9045(84)90003-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamimura S., Takahashi W. Strong convergence of a proximal-type algorithm in a Banach space. SIAM J. Optim. 2012;13(3):938–945. doi: 10.1137/S105262340139611X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu H.K. Nonlinear Analysis. 1991. Inequalities in Banach spaces with applications; pp. 1127–1138. [Google Scholar]