Abstract

Introduction:

Deficiency of Vitamin D is a widespread problem. Vitamin D could have important immune modulatory effects in psoriasis.

Objective:

Aimed to review and endeavored to establish the relationship, if any, between deficiency of Vitamin D and psoriasis.

Methods:

Leading studies that examined the relationship between deficiency of Vitamin D and psoriasis were reviewed from July2016 to October 2016. An electronic published work search was performed using PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and Saudi Digital Library.

Results:

A total of 2132 eligible articles were identified by the electronic search. The titles and abstracts of 954 articles fulfilled the criteria of midline search. 20 articles were included after application of inclusion standards and full-text review. These 20 studies included 2046 psoriatic patients with or without arthritis and 6508 healthy controls. 14 studies show a positive correlation between Vitamin D deficiency and psoriasis. These 14 studies included 1249 psoriatic patients with or without arthritis and 680 healthy controls. Remaining six studies, including 797 psoriatic patients with or without arthritis and 5828 healthy controls do not depict a positive correlation between the two variables under study.

Conclusion:

There exists a correlation of psoriasis with deficiency of Vitamin D. However, there is a need for larger scale case–control studies to assess how far Vitamin D deficiency plays a role in psoriasis.

Keywords: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol); 25 (OH)D(calcifediol) level; psoriasis; Vitamin D

Introduction

Vitamin D is an oil-soluble vitamin involved in bone metabolism, calcium absorption, skeletal mineralization, calcium, and phosphorous homeostasis and has numerous physiological and metabolic functions.[1-3] Vitamin D deficiency is now a worldwide problem and recognized as a pandemic affecting global health.[4,5] Deficiency of Vitamin D can be a result of insufficient or absent exposure to sunlight; malabsorption; accelerated catabolism from certain medications; and minimal amounts of Vitamin D in human breast milk. Anti-seizure medications such as phenobarbital, phenytoin, and primidone; anti-tuberculosis drug such as rifampicin; cholesterol-lowering drugs such as cholestyramine and colestipol can accelerate the catabolism of Vitamin D.[6-9]

Vitamin D has several important functions and has a significant place in human health. A number of studies showed a high occurrence of Vitamin D deficiency among aged males and females, immature adults, and children. Levels of Vitamin D in the serum are consistently changing, after summer it reaches at maximum while after winter it reaches its minimum.[10-20] Vitamin D is believed to be synthesized from exposure to sun. Whereas UVB exposure helps keratinocytes in the epidermis to synthesize pre Vitamin D3, later converted to active Vitamin D known as 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3. Vitamin D has many biological functions such as multiplication and differentiation of keratinocytes, maintaining the cycle of hair follicles, and suppressing tumors. Studies have established that Vitamin D also exhibits photoprotective, anti-inflammatory and wound healing effects.[21-26]

Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PA) belong to inflammatory disorders with genetic predisposition involving skin, joints, and immune system. The pathogenesis of psoriasis is not completely understood. Records are available of psoriasis being treated with oral intake of Vitamin D.[27] Role of oral administration of Vitamin D supplements for the treatment of psoriatic skin was first described 60 years ago based on the beneficial effects of UVR on the disease.[27] However, the risks of calcemic side effects wear away the benefit of oral administration of Vitamin D. These side effects include hyperglycemia, hypercalcemia, and decrease in bone density. Today, topical calcipotriol, a Vitamin D analog, is practiced efficaciously in the treatment of psoriasis. It is safe and good for the treatment of psoriasis without systemic side effects.[27,28]

Several studies indicate that Vitamin D suppresses the production of IL-2, IL-6, and interferon gamma, which are potent mediators of inflammation. Surveys have also verified the existence of an interplay between T helper cells (Th17) and Vitamin D in psoriatic patients. Moreover, Vitamin D promotes suppressor T-cell activity and inhibits cytotoxic and natural killer cell formation. It has been suggested that a combination of the mechanisms of reduced cellular proliferation, increased cellular differentiation, and immunomodulation may explain the therapeutic effects of topical Vitamin D and its analogs on psoriatic lesions. However, Vitamin D treatment is not effective for all patients with psoriasis. Due to this, the exact mechanism of action of Vitamin D in psoriasis and the etiology of the disease should be clarified.[27-29] There is a need to establish the precise action of Vitamin D in psoriasis which is also the aim of this review. With this objective, literature review was conducted to find if there is indeed a correlation between Vitamin D deficiency in the serum and occurrence of psoriasis.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

The author consulted earlier observational and controlled trial studies that established a correlation between Vitamin D and psoriasis, to develop a set of rules for the current study. For inclusion, the following criteria were set: (i) Comparison of 25-hydroxy Vitamin D (25(OH)D) and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D) in psoriatic patients with healthy patients, (ii) any measure of Vitamin D serum levels in winter and summer was accepted, (iii) male or female participants irrespective of age, (iv) retrospective and observational prospective (cross-sectional, case–control, and cohort) studies were taken into consideration, (v) randomized, as well as non-randomized interventional studies were included, (vi) studies were included that differed on methodological sample size quality, and (vii) studies were included irrespective of the date of publication.

Exclusion criteria

Articles available in a language other than English were excluded. All studies lacking healthy human controls were also excluded.

Search strategy

All relevant articles in public domain were searched on PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and Saudi Digital Library from July 2016 to October 2016. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses was used to search relevant articles. This was supported using a checklist and phase flow diagram to improve the quality of the review.[30] The search strategy was based on a selected vocabulary and relevant keywords. Articles were identified using the following search parameters: “Vitamin D;” “25(OH) D(calcifediol);” “25(OH)D (calcifediol) level;” “1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol);” “1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol) level;” “psoriatic patients;” “psoriasis;” and “PA.”

Data extraction

Only publications that met the criteria of PubMed ID number and other publication details were used to extract the data.

Results

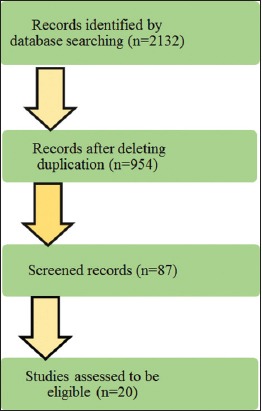

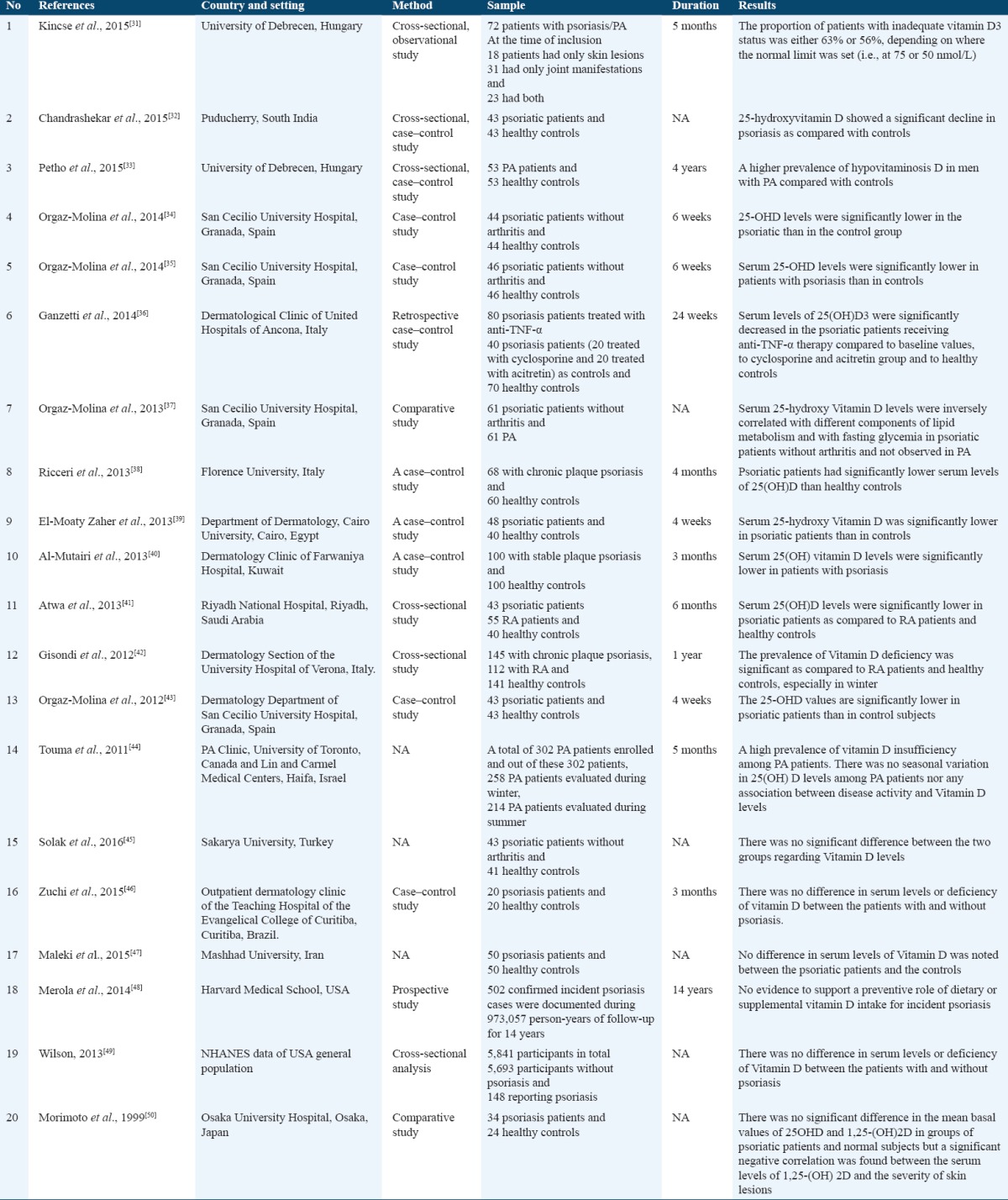

By searching PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and Saudi Digital Library, a total of 2132 eligible articles were identified. The titles and abstracts of 954 articles fulfilled the search criteria. Post sorting on applying inclusion standards and reviews were left with 20 articles that cleared the benchmark [Figure 1]. A total of 20 studies summarize the correlation between deficiency of Vitamin D and psoriasis [Table 1]. Duration of these studies ranged from 4 weeks to 14 years. Sample size of these 20 studies included: 2046 psoriatic patients with or without arthritis, 167 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and 6508 healthy controls. 14 studies are in favor of a positive correlation between Vitamin D deficiency and psoriasis. Sample size of these 14 studies included: 1249 psoriatic patients with or without arthritis, 167 patients with RA and 680 healthy controls. Remaining six studies do not depict a positive correlation between Vitamin D deficiency and psoriasis. Sample size of these 6 studies included: 797 psoriatic patients with or without arthritis and 5828 healthy controls.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process

Table 1.

Association between Vitamin D deficiency and psoriasis

Discussion

Deficiency of Vitamin D has been implicated as an environmental trigger for immune-mediated disorders including psoriasis and PA. There have been many studies conducted to know the association between Vitamin D deficiency and psoriasis.[31-44] Data published showed a positive correlation between deficiency of Vitamin D and the severity of psoriasis and PA in many studies.[31-44] In contrast with these, few studies showed no correlation between them.[45-50] Kincse et al. in their study of 72 psoriatic patients, PA and both concluded that an inverse correlation exists between the serum levels of Vitamin D3 and the severity of psoriasis, as well as the activity of PA was significantly higher in patients with inadequate Vitamin D3 status.[31] Chandrashekar et al. in their study comparing serum 25-hydroxy Vitamin D levels in 43 psoriatic patients with age and sex matched 43 healthy controls found that psoriatic patients had lower levels of 25-hydroxy Vitamin D as compared to controls and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.002). Furthermore, they also demonstrated a significant negative correlation of 25-hydroxy Vitamin D levels with psoriasis area and severity index in their psoriatic patients.[32]

Petho et al. found a higher prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in 53 men with PA compared with healthy controls.[33] Orgaz-Molina et al. in their study of 44 psoriatic patients found that the levels of 25-OHD were markedly lower in patients with psoriasis when compared to the control group.[34] Another study conducted by Orgaz-Molina et al. showed that their 46 psoriatic patients had lower levels of 25-hydroxy Vitamin D as compared to controls and the difference was statistically significant (30.5 ± 9.3 vs. 38.3 ± 9.6 ng/ml; P < 0.0001).[35]

Ganzetti et al. compared 80 psoriasis patients treated with anti-TNF-α with 40 psoriasis patients (20 treated with cyclosporine and 20 treated with acitretin) and 70 healthy controls. Their results showed significantly decreased serum levels of Vitamin D in psoriatic patients receiving anti-TNF-α therapy compared to baseline values, to cyclosporine and acitretin group and to healthy controls.[36] Orgaz-Molina et al. in their comparative study of 61 psoriatic patients without arthritis with 61 PA patients concluded that serum 25-(OH) D was inversely related to lipid and glucose metabolism parameters in psoriatic patients without arthritis, whereas no such association was observed in psoriatic patients with arthritis.[37]

Ricceri et al. in their study comparing serum 25-hydroxy Vitamin D levels in 68 chronic plaque psoriasis patients and 60 healthy controls found that psoriatic patients had significantly (P < 0.05) poorer levels of 25(OH) D than healthy controls.[38] A case–control study conducted by El-Moaty Zaher et al. showed that their 48 psoriatic patients had lower readings of 25-hydroxy Vitamin D as compared to 40 healthy controls and the difference was statistically significant (21.05 ± 3.66 vs. 37.02 ± 5.06 ng/ml; P < 0.000).[39]

Al-Mutairi et al. in their study comparing 100 stable plaque psoriasis patients with 100 age and sex matched healthy controls found significantly (29.53 ± 9.38 vs. 53.5 ± 19.6 ng/ml; P < 0.0001) lower serum Vitamin D levels in psoriatic patients as compared to the control group.[40] Atwa et al. in their cross-sectional study of 43 psoriatic patients, 55 RA patients, and 40 healthy controls revealed that the levels of 25(OH) D were markedly (11.74 ± 3.60, 15.45 ± 6.42, and 24.55 ± 11.21 ng/ml; P < 0.000) lower in psoriatic patients as compared to RA patients and healthy controls.[41] Gisondi et al. in their cross-sectional study comparing serum Vitamin D levels in 145 chronic plaque psoriasis patients with 112 RA patients and 141 healthy controls found that 25(OH) D was significantly low in psoriatic patients compared with RA or healthy control groups.[42]

Orgaz-Molina et al. in their study comparing serum 25-hydroxy Vitamin D levels in 43 psoriatic patients with age and sex matched 43 healthy controls found that psoriatic patients had lower levels of 25-hydroxy Vitamin D as compared to healthy controls and the difference was statistically significant (24.41 ± 7.80 vs. 29.53 ± 9.38 ng/ml; P < 0.007).[43] Touma et al. in their study of 302 PA patients (out of these 302 patients, 258 patients evaluated during winter and 214 patients evaluated during summer), demonstrated that PA patients had high prevalence of Vitamin D insufficiency but there was no seasonal variation in 25(OH) D levels nor there was any association between disease activity and Vitamin D levels in these patients.[44]

Solak et al. compared serum levels of 25-OH Vitamin D between 43 psoriatic patients without arthritis and 41 healthy controls and found that there was no significant difference between the two groups.[45] Zuchi et al. in their case–control study comparing serum levels of Vitamin D between 20 psoriasis patients and 20 healthy controls found no significant differences between patients with psoriasis and controls.[46] In a study conducted by Maleki et al., comparing serum Vitamin D levels in 50 patients with psoriasis with 50 healthy controls found no statistically significant difference in serum levels of Vitamin D between the psoriatic patients and the controls.[47] Moreover, Merola et al. found no evidence of the role of dietary or supplementary Vitamin D intake and the onset of psoriasis.[48] Wilson in his cross-sectional analysis of 5841 participants in total (5693 participants without psoriasis and 148 reporting psoriasis) found no difference in serum levels of Vitamin D between patients with and without psoriasis.[49] Morimoto et al. in their comparative study of 34 psoriatic patients and 24 healthy controls concluded no significant difference in the mean basal values of 25OHD and 1,25-(OH) 2D in groups of psoriatic patients and controls.[50]

The studies which showed the inverse correlation between the serum levels of vitamin 25(OH) D3 and psoriasis, PA and severity of psoriasis draw attention to the importance of Vitamin D3 status in these patients and stress its regular and routine monitoring in patients with psoriasis or PA. Studies have also shown that psoriasis or PA are also associated with metabolic syndrome, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, and an increased risk of cardiovascular events in these patients.[35,37,51-53] Some of the studies included in this review also highlight the importance of monitoring serum levels of Vitamin D3 in psoriasis to measure the risk of metabolic complications in psoriatic patients.[34,35,37,40]

Comparison of the two groups of studies reveals that the number of patients in the group (patient number = 1249) which supports the hypothesis of a positive correlation between Vitamin D deficiency and psoriasis is more as compared to the group of studies which showed no correlation between Vitamin D deficiency and psoriasis (patient number = 797). In the group which showed no correlation between Vitamin D deficiency and psoriasis, out of 797 total patients in this group, one study including 502 patients[48] showed no evidence to support a preventive role of dietary or supplemental inclusion of Vitamin D as a preventive measure for psoriasis. There was no control group in this study which can compare the serum levels of Vitamin D in psoriatic patients and healthy controls.

Conclusions

This review showed that there is an association between deficiency of Vitamin D and psoriasis, but larger scale case–control studies are required that would show an accurate and effective role of Vitamin D deficiency in psoriasis. Moreover, study trials should also be conducted to see the beneficial role of Vitamin D supplementation in psoriatic patients.

References

- 1.Kulie T, Groff A, Redmer J, Hounshell J, Schrager S. Vitamin D: An evidence-based review. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:698–706. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.06.090037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoffman N, Gordon CM. Vitamin D and adolescents: What do we know? Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:465–71. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32832da096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lips P. Vitamin D physiology. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2006;92:4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holick MF, Chen TC. Vitamin D deficiency: A worldwide problem with health consequences. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1080S–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.1080S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehmann B, Meurer M. Vitamin D metabolism. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:2–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Mohaimeed A, Khan NZ, Naeem Z, Al-Mogbel E. Vitamin D status among women in middle east. J Health Sci. 2012;2:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tangpricha V, Luo M, Fernández-Estívariz C, Gu LH, Bazargan N, Klapproth JM, et al. Growth hormone favorably affects bone turnover and bone mineral density in patients with short bowel syndrome undergoing intestinal rehabilitation. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2006;30:480–6. doi: 10.1177/0148607106030006480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koutkia P, Lu Z, Chen TC, Holick MF. Treatment of vitamin D deficiency due to crohn’s disease with tanning bed ultraviolet B radiation. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1485–8. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gartner LM, Greer FR Section on Breastfeeding, and Committee on Nutrition. American academy of pediatrics. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency: New guidelines for vitamin D intake. Pediatrics. 2003;111:908–10. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu BA, Gordon M, Labranche JM, Murray TM, Vieth R, Shear NH. Seasonal prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in institutionalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:598–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb03094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott ME, Binkley NC, Carnes M, Zimmerman DR, Petersen K, Knapp K, et al. Fracture risks for women in long-term care: High prevalence of calcaneal osteoporosis and hypovitaminosis D. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:702–10. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.6.702.32182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas MK, Lloyd-Jones DM, Thadhani RI, Shaw AC, Deraska DJ, Kitch BT, et al. Hypovitaminosis D in medical inpatients. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:777–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803193381201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tangpricha V, Pearce EN, Chen TC, Holick MF. Vitamin D insufficiency among free-living healthy young adults. Am J Med. 2002;112:659–62. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01091-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karalius VP, Zinn D, Wu J, Cao G, Minutti C, Luke A, et al. Prevalence of risk of deficiency and inadequacy of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in US children: NHANES 2003-2006. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014;27:461–6. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2013-0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang LL, Wang HY, Wen HK, Tao HQ, Zhao XW. Vitamin D status among infants, children, and adolescents in southeastern China. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2016;17:545–52. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1500285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shoben AB, Kestenbaum B, Levin G, Hoofnagle AN, Psaty BM, Siscovick DS, et al. Seasonal variation in 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in the cardiovascular health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:1363–72. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wielen RP, Löwik MR, Berg H, Groot LC, Haller J, Moreiras O, et al. Serum vitamin D concentrations among elderly people in Europe. Lancet. 1995;346:207–10. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gannagé-Yared MH, Chemali R, Yaacoub N, Halaby G. Hypovitaminosis D in a sunny country: Relation to lifestyle and bone markers. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1856–62. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.9.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Looker AC, Gunter EW. Hypovitaminosis D in medical inpatients. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:344–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuleihan GE, Deeb M. Hypovitaminosis D in a sunny country. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1840–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906103402316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishal AA. Effects of different dress styles on vitamin D levels in healthy young Jordanian women. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:931–5. doi: 10.1007/s001980170021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clemens TL, Adams JS, Henderson SL, Holick MF. Increased skin pigment reduces the capacity of skin to synthesise vitamin D3. Lancet. 1982;1:74–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris SS, Soteriades E, Coolidge JA, Mudgal S, Dawson-Hughes B. Vitamin D insufficiency and hyperparathyroidism in a low income, multiracial, elderly population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4125–30. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nesby-O’Dell S, Scanlon KS, Cogswell ME, Gillespie C, Hollis BW, Looker AC, et al. Hypovitaminosis D prevalence and determinants among African American and white women of reproductive age: Third national health and nutrition examination survey 1988-1994. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:187–92. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holick MF. Vitamin D: Importance in the prevention of cancers, Type 1 diabetes, heart disease, and osteoporosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:362–71. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bikle DD, Pillai S. Vitamin D, calcium, and epidermal differentiation. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:3–19. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahriari M, Kerr PE, Slade K, Grant-Kels JE. Vitamin D and the skin. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:663–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kragballe K. Calcipotriol: A new drug for topical psoriasis treatment. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;77:241–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1995.tb01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sintov AC, Yarmolinsky L, Dahan A, Ben-Shabat S. Pharmacological effects of vitamin D and its analogs: Recent developments. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19:1769–74. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liberati A, Altman DJ, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kincse G, Bhattoa PH, Herédi E, Varga J, Szegedi A, Kéri J, et al. Vitamin D3 levels and bone mineral density in patients with psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis. J Dermatol. 2015;42:679–84. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandrashekar L, Kumarit GR, Rajappa M, Revathy G, Munisamy M, Thappa DM. 25-hydroxy vitamin D and ischaemia-modified albumin levels in psoriasis and their association with disease severity. Br J Biomed Sci. 2015;72:56–60. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2015.11666797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petho Z, Kulcsar-Jakab E, Kalina E, Balogh A, Pusztai A, Gulyas K, et al. Vitamin D status in men with psoriatic arthritis: A case-control study. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26:1965–70. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orgaz-Molina J, Magro-Checa C, Rosales-Alexander JL, Arrabal-Polo MA, Castellote-Caballero L, Buendía-Eisman A, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency is associated with higher carotid intima-media thickness in psoriatic patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:53–62. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orgaz-Molina J, Magro-Checa C, Arrabal-Polo MA, Raya-Álvarez E, Naranjo R, Buendía-Eisman A, et al. Association of 25-hydroxyvitamin D with metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis: A case-control study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:142–5. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ganzetti G, Campanati A, Scocco V, Brugia M, Tocchini M, Liberati G, et al. The potential effect of the tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors on vitamin D status in psoriatic patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:715–7. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orgaz-Molina J, Magro-Checa C, Rosales-Alexander JL, Arrabal-Polo MA, Buendía-Eisman A, Raya-Alvarez E, et al. Association of 25-, Robin YM, et al. Neo/adjuvant chemotherapy does not improve outcome in resected primary synovial sarcom. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:938–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ricceri F, Pescitelli L, Tripo L, Prignano F. Deficiency of serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D correlates with severity of disease in chronic plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:5112. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaher HA, El-Komy MH, Hegazy RA, Khashab HA, Ahmed HH. Assessment of interleukin-17 and vitamin D serum levels in psoriatic patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:840–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Mutairi N, El-Eassa BE, Nair V. Measurement of vitamin D and cathelicidin (LL-37) levels in patients of psoriasis with co-morbidities. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:492–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.113077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atwa MA, Balata MG, Hussein AM, Abdelrahman NI, Elminshawy HH. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration in patients with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis and its association with disease activity and serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Saudi Med J. 2013;34:806–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gisondi P, Rossini M, Cesare AD, Idolazzi L, Farina S, Beltrami G, et al. Vitamin D status in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:505–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orgaz-Molina J, Buendía-Eisman A, Arrabal-Polo MA, Ruiz JC, Arias-Santiago S. Deficiency of serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in psoriatic patients: A case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:931–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Touma Z, Eder L, Zisman D, Feld J, Chandran V, Rosen CF, et al. Seasonal variation in vitamin D levels in psoriatic arthritis patients from different latitudes and its association with clinical outcomes. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:1440–7. doi: 10.1002/acr.20530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Solak B, Dikicier BS, Celik HD, Erdem T. Bone mineral density, 25-OH vitamin D and inflammation in patients with psoriasis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2016;32:153–60. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zuchi MF, Pde OA, Tanaka AA, Schmitt JV, Martins LE. Serum levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D in psoriatic patients. An Bras Derm. 2015;90:430–2. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maleki M, Nahidi Y, Azizahari S, Meibodi NT, Hadianfar A. Serum 25-OH vitamin D level in psoriatic patients and comparison with control subjects. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:207–10. doi: 10.1177/1203475415622207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Merola JF, Han J, Li T, Qureshi AA. No association between vitamin D intake and incident psoriasis among US women. Arch Dermatol Res. 2014;306:305–7. doi: 10.1007/s00403-013-1426-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson PB. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status in individuals with psoriasis in the general population. Endocrine. 2013;44:537–9. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-9989-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morimoto S, Yoshikawa K, Fukuo K, Shiraishi T, Koh E, Imanaka S, et al. Inverse relation between severity of psoriasis and serum 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D level. J Dermatol Sci. 1990;1:277–82. doi: 10.1016/0923-1811(90)90120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Menter A, Griffiths CE, Tebbey PW, Horn EJ, Sterry W. Exploring the association between cardiovascular and other disease-related risk factors in the psoriasis population: The need for increased understanding across the medical community. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1371–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arias-Santiago S, Orgaz-Molina J, Castellote-Caballero L, Arrabal-Polo MA, Garcia-Rodriquez S, Perandres-Lopez R, et al. Atheroma plaque, metabolic syndrome and inflammation in patients with psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:337–44. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2012.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia-Rodriquez S, Arias-Santiago S, Perandres-Lopez R, Castellote L, Zumaquero E, Navarro P, et al. Increased gene expression of toll-like receptor 4 on peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:242–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]