Abstract

Introduction:

Hand hygiene is one of the most important ways to reduce the prevalence of nosocomial infections, morbidity, mortality, and health-care costs among hospitalized patients worldwide.

Objectives:

We addressed this study to assess knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding hand hygiene guidelines among health-care workers.

Methods:

A multicenter cross-sectional study conducted from October to December 2015 including three hospitals in Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia. A total of 354 participants completed a self-administered survey on knowledge, attitudes, and practices of hand hygiene. Analysis of variance was used to compare knowledge level across age, gender, profession, and hospitals. All analyses were performed with SPSS, version 21.

Results:

Overall, the average knowledge score was 63%. There were significant differences in knowledge level across groups. Health-care workers over the age of 30 had higher scores than those younger than 30. Health-care workers at the tertiary hospital had higher scores than those at the secondary hospitals. Nearly, all reported positive attitudes toward hand hygiene as well as adhering to the guidelines regularly. Further, they reported that soap and water were the most common agents for cleaning hands.

Conclusion:

The study findings indicate that there are gaps in the knowledge, which could be addressed with brief and more frequent training sessions, particularly in the secondary hospitals. However, the hand hygiene guidelines are well-known by the staff and well promoted in the hospitals reflected by the positive attitudes. Further improvements in adherence to the hand hygiene guidelines will continue to decrease the likelihood of nosocomial infections.

Keywords: Hand hygiene, nosocomial infections, Saudi Arabia, WHO guidelines

Introduction

Hospital-acquired infections, also known as nosocomial infections, affect 5–10% of hospitalized patients in developed countries and 20% of patients in developing countries.[1] Infections have a variety of effects on patients including but not limited to extended stays in the hospital, pneumonia, and death.[2] Further, hospital-acquired infections increase the financial burden of families as well as the health-care systems.[3] Another complication is that infections are difficult to treat with antibiotics; drug resistance is becoming more common particularly among Gram-negative bacteria.[4,5]

Proper hand hygiene among health-care workers can significantly reduce the transmission of bacterial organisms.[6] Unfortunately, adherence to hand hygiene guidelines and proper hand washing techniques among health-care workers are uncommon[7-9] even after educational efforts. Some studies suggest that after educational programs, 40–50% adherence rates to proper hand hygiene are feasible; however, a few studies have shown that adherence can be improved to as high as 80%.[10,11]

The World Health Organization has started an international hand hygiene initiative entitled “My 5 Moments.” These five moments that call for the use of hand hygiene include the moment before touching a patient, before performing aseptic and cleaning procedures, after being at risk of exposure to body fluids, after touching a patient, and after touching patient surroundings. The concept of this initiative is that it is easy to understand and memorize and it is based on the geographical areas of the “patient-zone” and the “health-care zone.” This initiative was adopted and tested in several countries including Saudi Arabia.[12-14] The study showed an increase in compliance from 51% to 67%.[13]

Since this adoption of the “My 5 Moments” initiatives, studies have been conducted in Saudi Arabia that (1) address non-compliance with hand hygiene in medical facilities and (2) assess knowledge about hand hygiene among medical students. The first set of studies suggest that certain factors are associated with non-compliance to hand hygiene guidelines.[15,16] Example factors include being a physician (vs. nurse), before patient contact (vs. other four moments), and having a morning shift (vs. evening). The second study has shown that medical students correctly identify the importance of hand hygiene, but their understanding of the guidelines is weak.[17] Many students are confused about the appropriate indications for hand washing (soap and water) versus hand rubbing (alcohol agent). The former is the superior method for reducing the transmission of organisms.

Understanding and adherence to the “5 moments” of hand hygiene are essential in the medical facilities among health-care workers. The purpose of the present study was to assess knowledge, attitudes, and practices of health-care workers in Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia. The secondary objective was to assess whether there were any knowledge differences across factors such as age, gender, profession, and hospitals (secondary vs. tertiary).

Methods

Overview

A cross-sectional study was conducted at three governmental hospitals: (1) King Fahad Specialized Hospital (KFSH) which is a tertiary center, (2) Buraidah Central Hospital (BCH), and (3) Al Rass General Hospital (AGH); the latter is secondary centers. All three centers are located in Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia. A total number of 345 respondents were included in the study. Data collection was carried out for 3 months from October to December 2015 using a self-administered questionnaire. The study purpose and procedures were explained to the participants and informed consent was taken on enrollment. The study protocol was approved by Qassim Regional Research Ethics committee in September 2015 and the Medical Research Center Ethical Committee at Qassim University in October 2015.

Questionnaire

The instrument was designed to assess knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to hand hygiene among the health-care workers in all three hospitals. The questionnaire included 25 questions for knowledge, 5 questions for attitudes, and 5 for practices. The knowledge assessment was based on the hand hygiene knowledge questionnaire for health-care workers from the World Health Organization (2009). Assessment of attitudes and practices was validated questions from earlier studies.[18,19]

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics including frequency distributions and central tendencies were conducted. Knowledge score was computed; each item was allotted 1 point, and then, the score was converted to a percent out of 100. Analysis of variance – one-way was used to determine whether the knowledge scored varied across demographic characteristics such as age, gender, profession, or hospital. All analyses were performed with SPSS, version 21.

Results

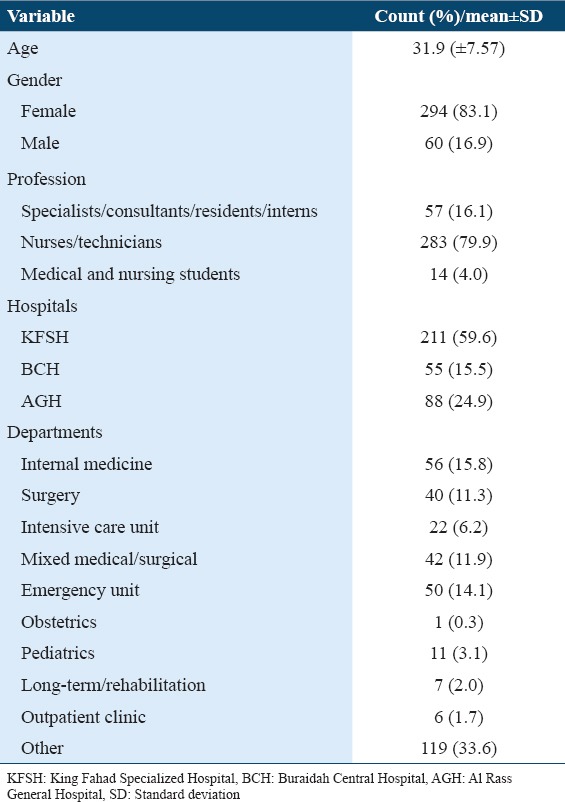

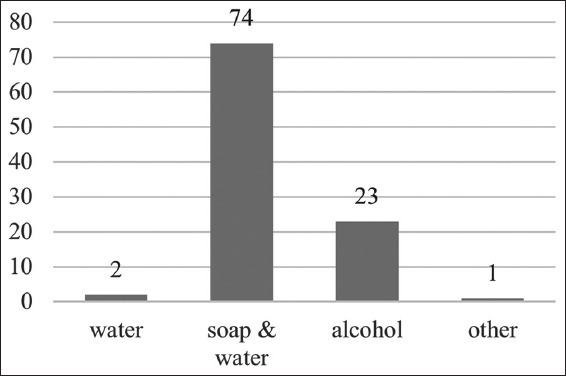

The sample consisted of mostly female (83%) nurses (80%) from a variety of departments at three hospitals. Most of the nurses were recruited from the KFSH (60%). Their ages ranged from 20 to 59 with a mean of 32 [Table 1]. The nurses reported using soap and water as the main agent for hand hygiene. Alcohol and other agents were used <25% of the time [Figure 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of health-care workers in Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia (n=354)

Figure 1.

Commonly used agents for hand hygiene among health-care workers in Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia (n = 354)

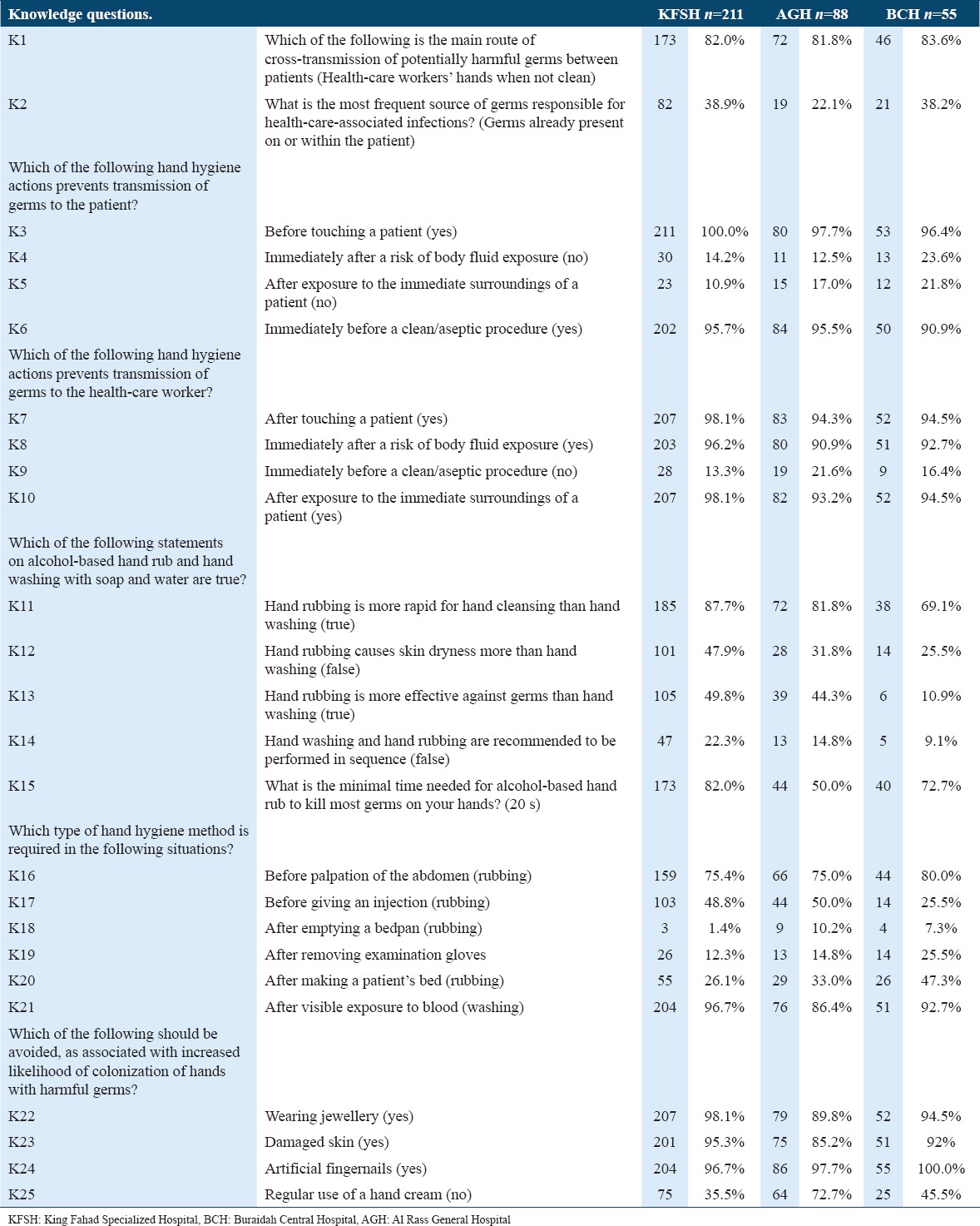

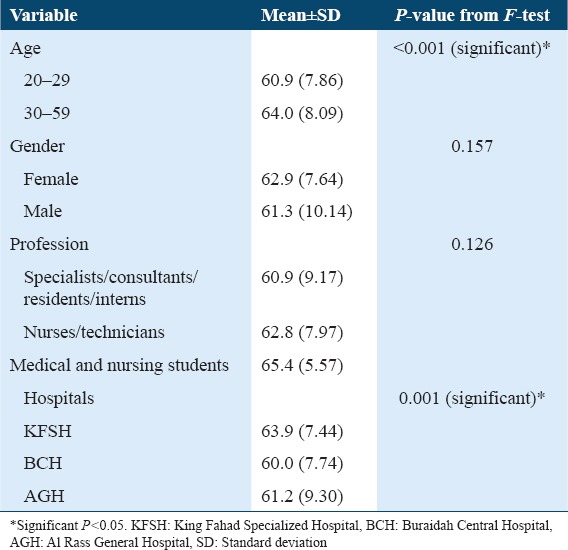

However, the health-care workers had low scores on the knowledge assessment [Table 2]. The average score was 62.6 (standard deviation = 8.12) on a 100 point scale. The scores ranged from 36 to 88% with a normal distribution [Figure 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of knowledge in different hospitals regarding various aspects of hand hygiene practices

Figure 2.

Distribution of hand hygiene knowledge score among health-care workers in Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia (n = 354)

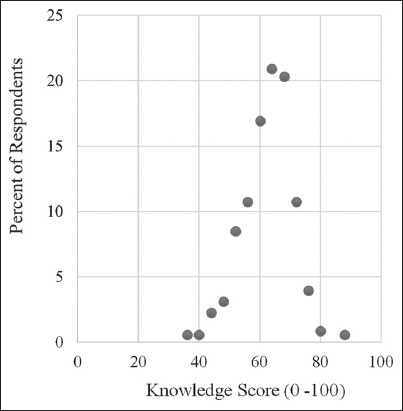

The participants did not clearly distinguish which actions prevented transmission to the patient versus actions that prevented transmission to the health-care workers. Furthermore, it was unclear whether washing or rubbing was required in certain situation such as after emptying a bedpan. There were no significant differences in hand hygiene knowledge between males and females or across professional levels (specialists vs. nurses vs. students). There were significant differences by age and by institution. Health-care workers aged 30 and above had significantly higher knowledge score than those aged 20–29 (P < 0.001). Further, health-care workers at the KFSH had significantly higher knowledge scores than health-care workers at either Buraidah Central or AGH (P = 0.001) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Differences in hand hygiene knowledge score across selected demographic characteristics among health-care worker in Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia (n=354)

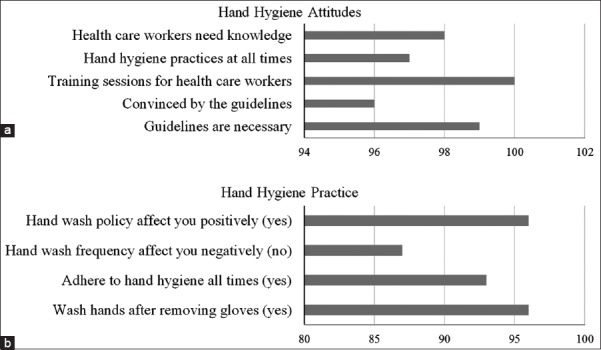

Overall, they reported positive attitudes toward hand hygiene. More than 90% of them reported that the hospital policies affect them positively and they adhere to the guidelines at all times [Figure 3a]. Further, nearly, all health-care workers endorsed that they need training and knowledge on hand hygiene that the guidelines are necessary and that hand hygiene should be followed at all times [Figure 3b].

Figure 3.

Hand hygiene (a) attitudes and (b) practices among health-care workers in Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia (n = 354)

Discussion

The main finding of the study was that the knowledge scores were low, overall, among health-care workers in Al-Qassim hospitals; also, there were significant differences between older and younger health-care workers (>30 years) as well as between the secondary and tertiary hospitals. Results indicating low knowledge level are in line with other studies in Saudi Arabia[17,20] as well as internationally.[18,21] There is a caveat that should be noted; when we examined incorrect responses to individual questions, we found that many respondents identified “hand washing” as necessary when “hand rubbing” was sufficient. This type of error in understanding or implementation would not increase infections, but in fact, they may be overcompensating. To date, this is the first study in Saudi Arabia to compare hand hygiene knowledge across different institutions. Hence, this is a novel finding that tertiary hospitals may have a more knowledgeable staff regarding hand hygiene than secondary hospitals.

The second main finding of the study was that health-care workers have a positive attitude toward hand hygiene guidelines. They recognize their importance and report that they try to follow them all of the time. This finding is similar to the studies that have assessed attitudes toward hand hygiene in medical settings.[17,22] Overall, appreciation for the importance of good hand hygiene is high, particularly among advanced medical students and those health-care workers in training.

Although this study assesses knowledge, practices, and attitudes regarding hand hygiene, the data are limited because it is self-reported. To assess hand hygiene practices more accurately, one would need to assess the behavior objectively through selected observations. Studies that have assessed adherence to guidelines through observation have found that rate of adherence is ranged between 34% and 50% (number of hand hygiene performance/number of hand hygiene opportunities) with physicians showing slightly lower adherence than nurses and technicians.[7,8,16,21]

Beyond self-reported data, the study has some limitations. The sample selection was not conducted evenly across sample characteristics; hence, some subgroup comparisons could not be made because of small sample sizes. For example, if you wanted to compare knowledge level among older physicians compared to young physicians. Furthermore, this study was conducted in Al-Qassim region and thus is not representative of the entire country. Therefore, the finding is only generalizable to this region and not to all of Saudi Arabia.

Conclusion

We conclude that there are gaps in the knowledge, which could be addressed with brief and more frequent training sessions, particularly in the secondary hospitals. However, hand hygiene guidelines are well-known by the hospital staff, including nurses and physicians, and well-promoted in the hospitals reflected by the positive staff attitudes. Future research should consider assessing hand hygiene adherence using observational measurement.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to Dr. Khadija Dandash from Family and Community Medicine Department at Qassim University, for providing helpful comments. Furthermore, we would like to thank all of our study participants for volunteering and their kind cooperation.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Healthcare Associated Infections. [2015 Dec 31]. Available from: http://www.who.int/gpsc/country_work/gpsc_ccisc_fact_sheet_en.pdf .

- 2.Glance LG, Stone PW, Mukamel DB, Dick AW. Increases in mortality, length of stay, and cost associated with hospital-acquired infections in trauma patients. Arch Surg. 2011;146:794–801. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimlichman E, Henderson D, Tamir O, Franz C, Song P, Yamin CK, et al. Health care-associated infections:A meta-analysis of costs and financial impact on the US health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:2039–46. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindsay JA. Hospital-associated MRSA and antibiotic resistance-what have we learned from genomics? Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303:318–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knight GM, Budd EL, Whitney L, Thornley A, Al-Ghusein H, Planche T, et al. Shift in dominant hospital-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (HA-MRSA) clones over time. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2514–22. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Tawfiq JA, Tambyah PA. Healthcare associated infections (HAI) perspectives. J Infect Public Health. 2014;7:339–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AlNakhli DJ, Baig K, Goh A, Sandokji H, Din SS. Determinants of hand hygiene non-compliance in a cardiac center in saudi arabia. Saudi Med J. 2014;35:147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alsubaie S, Maither Ab, Alalmaei W, Al-Shammari AD, Tashkandi M, Somily AM, et al. Determinants of hand hygiene noncompliance in intensive care units. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41:131–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basurrah MM, Madani TA. Handwashing and gloving practice among health care workers in medical and surgical wards in a tertiary care centre in riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38:620–4. doi: 10.1080/00365540600617025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Dorzi HM, Matroud A, Al Attas KA, Azzam AI, Musned A, Naidu B, et al. Amultifaceted approach to improve hand hygiene practices in the adult intensive care unit of a tertiary-care center. J Infect Public Health. 2014;7:360–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Tawfiq JA, Abed MS, Al-Yami N, Birrer RB. Promoting and sustaining a hospital-wide, multifaceted hand hygiene program resulted in significant reduction in health care-associated infections. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41:482–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sunkesula VC, Meranda D, Kundrapu S, Zabarsky TF, McKee M, Macinga DR, et al. Comparison of hand hygiene monitoring using the 5 moments for hand hygiene method versus a wash in-wash out method. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:16–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allegranzi B, Gayet-Ageron A, Damani N, Bengaly L, McLaws ML, Moro ML, et al. Global implementation of WHO's multimodal strategy for improvement of hand hygiene:A quasi-experimental study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:843–51. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazi W, Senok AC, Al-Kahldy S, Abdullah D. Implementation of the world health organization hand hygiene improvement strategy in critical care units. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2013;2:15. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bukhari SZ, Hussain WM, Banjar A, Almaimani WH, Karima TM, Fatani MI, et al. Hand hygiene compliance rate among healthcare professionals. Saudi Med J. 2011;32:515–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahfouz AA, El Gamal MN, Al-Azraqi TA. Hand hygiene non-compliance among intensive care unit health care workers in aseer central hospital, south-western saudi arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e729–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamadah R, Kharraz R, Alshanqity A, AlFawaz D, Eshaq AM, Abu-Zaid A, et al. Hand hygiene:Knowledge and attitudes of fourth-year clerkship medical students at alfaisal university, college of medicine, riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2015;7:e310. doi: 10.7759/cureus.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nair SS, Hanumantappa R, Hiremath SG, Siraj MA, Raghunath P. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of hand hygiene among medical and nursing students at a tertiary health care centre in Raichur, India. ISRN Prev Med. 2014;2014:608927. doi: 10.1155/2014/608927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maheshwari V, Kaore NC, Ramnani VK, Gupta SK, Borle A, Kaushal R, et al. A study to assess knowledge and attitude regarding hand hygiene amongst residents and nursing staff in a tertiary health care setting of bhopal city. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:DC04–7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8510.4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herbert VG, Schlumm P, Kessler HH, Frings A. Knowledge of and Adherence to hygiene guidelines among medical students in Austria. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2013;2013:802930. doi: 10.1155/2013/802930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Tawfiq JA, Pittet D. Improving hand hygiene compliance in healthcare settings using behavior change theories:Reflections. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25:374–82. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2013.827575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amin TT, Al Noaim KI, Bu Saad MA, Al Malhm TA, Al Mulhim AA, Al Awas MA, et al. Standard precautions and infection control, medical students'knowledge and behavior at a saudi university:The need for change. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5:114–25. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n4p114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]