Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess institutional delivery and its associated factors in Benishangul-Gumez region, North-West of Ethiopia. The data were obtained at community level in a single survey within 1 month and there is no continuation of this study or previously published part elsewhere.

Results

Among the 428 eligible respondents recruited for this study, 427 of them responded completely to the interview, giving a response rate of 99.8%. Of the total (427) respondents, 51.1% women delivered the recent child at health facility in the 12 months preceding the survey. Among the common reasons for home delivery were, labour was urgent (25.8%), home birth was usual habit for them (23.9%) and distance to health center was too far. Age (AOR = 3.4, 95% CI 1.46, 7.97), husband occupation (AOR = 5.16, 95% CI 1.74, 15.31), frequency of antenatal care visit (AOR = 3.34, 95% CI 1.88, 5.94) and maternal knowledge on danger signs of pregnancy and delivery (AOR = 7.18, 95% CI 3.77, 13.66) were significantly associated factors with institutional delivery. Although, the prevalence of institutional delivery has improved when compared to previous reports, strategic modification is important to increase health facility delivery.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13104-018-3295-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Institutional delivery, Associated factors, Benishangul-Gumez, Ethiopia

Introduction

Globally, the total number of maternal deaths decreased by 45% from 523,000 in 1990 to 289,000 in 2013 with an annual rate of decline by 3.3% [1]. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), a woman’s risk of dying from preventable complications of pregnancy and childbirth is 1 in 22 [2]. The 99% (286,000) of the global maternal deaths occurred in developing countries, SSA region alone accounting for 62% (179,000) of these deaths [1]. Ethiopia is among countries with highest maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in the world with an estimated MMR of 676/100,000 live births and it is one of among the ten countries accounted for 58% of the global maternal deaths in 2013 [1, 3].

Though skill-attendance is the most important intervention to prevent life threatening complications [4, 5], most SSA women still give birth at home in the absence of skilled birth attendant (SBA) [4]. Worldwide, the major direct causes of maternal mortality are haemorrhage, sepsis, unsafe abortion; pregnancy induced hypertension and obstructed labour [6]. Haemorrhage alone accounts for one-third of all maternal deaths in Africa [7]. Wide disparities are found among regions in the level of health facility delivery ranging from nearly universal in Western to about 50% in Southern Asia and SSA [8]. Socio demographic variables, birth order, distance to health facility, exposure to media, frequency of antenatal care (ANC), knowledge on pregnancy and child birth danger signs, history of prolonged labour, and decision making status are among the major factors cited for low uptake of institutional delivery [4, 9–13].

Ethiopia in its’ Health Sector Development Plan IV’s targeted to increase SBA to 62% by 2015; but the coverage has reached 55% [14]. Literatures from Ethiopia also reported that institutional delivery ranges from 15 to 47% [11, 15]. So as to compensate this gap, Ethiopia in its health sector transformation plan has set a goal to increase SBA to 90% by 2019/20 [16]. Factors associated with institutional delivery appear to be context related and vary across ranges of studies in Ethiopia [9, 10, 17–19]. Therefore, it is a crucial point to identify contextual factors determining institutional delivery to help policy maker as guide for possible context based strategic modification of programs and interventions. Moreover, the study area is an emerging region and studies done in this area are limited.

Main text

Methods

Study setting

This study was conducted in Pawe district one of among the districts of Benishangul-Gumez Regional state in Ethiopia. Pawe district has 20 kebeles. Based on the information obtained from the district health office, the population of Pawe district was about 57,724 in 2014 of which, 13,882 were reproductive age group women (unpublished report). Community based cross sectional study was conducted from March 1 to March 30, 2015.

Sample size and sampling techniques

A single population proportion formula [n = (Z α/2)2 p(1 − p)/d2] was used to estimate the required sample size. The following assumptions were made while calculating the sample size. A 95% CI, 5% (d = 0.05) margin of error, population proportion of mothers who gave birth at health institution assumed to be 15.8% [15], design effect of 2 with an expectation of 10% of non-response rate. Overall, 428 respondents were recruited. The kebeles found in the district (17 rural kebeles and 3 urban kebeles) were stratified into rural and urban strata then lottery method was used to select five kebeles from the rural strata and one kebele from the urban strata to ensure representativeness. Proportional to population size allocation technique was used to allocate the sample size to each kebele. Census was done in each kebeles to identify households with eligible women and corresponding identification number was given to develop sampling frame. Then systematic sampling technique was used to recruit eligible respondents at every kth interval (k = 2, 3).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study population included all women who delivered within the last 12 months preceding the survey and residing in the selected kebeles at least for 6 months.

Data collection tool and procedures

A structured questionnaire was developed from different literatures in English and translated into ‘Amharic’ language (local language). Data were collected by six trained diploma midwives who can speak Amharic language through face to face interview. A pretest was conducted among 5% of the sample size in nearby district which has similar basic socio-demographic characteristics as the study district. The overall supervision was carried out by the principal investigator and supervisors. Ethical clearance was obtained from Institutional Ethical Review Board of Mekelle University, College of Health Sciences. A letter of permission was obtained from Metekel zonal Health Office to Pawe district Health Office then to the respective kebeles. Informed signed consent was obtained from study participants and consent for participants below 18 years old was taken from their father/mother.

Analysis

Data were checked and entered into Epi Info version 3.3.2 software, and exported to SPSS version 20 software for analysis. Variables with p < 0.2 at bivariate analysis were included in multivariable logistic regression analysis. Odds ratio along with 95% CI was computed to ascertain association between independent and dependent variables. p value of < 0.05 in the multivariable analysis was considered as cut off point to determine statistical test.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

Among the 428 eligible respondents recruited, 427 of them responded completely to the interview, giving a response rate of 99.8%. Majority, 318 (74.5%) of respondents were rural residents. The mean age of the respondents was 29.8 years (SD 7.4) with a range of 16–48 years old. The majority of respondents, 381 (89.2%) were married. About, 127 (29.7%) of respondents were had radio or television at home (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants in Pawe district, Benishangul-Gumez, Ethiopia March 2015

| Variable | Frequency N = 427 (%) |

|---|---|

| Religion | |

| Orthodox Christian | 202 (47.3) |

| Muslim | 131 (30.7) |

| Catholic | 40 (9.4) |

| Protestant | 36 (8.4) |

| Traditional | 18 (4.2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Amhara | 266 (62.3%) |

| Hadya | 44 (10.3%) |

| Oromo | 43 (10.1%) |

| Agew | 33 (7.7%) |

| Kembata | 24 (5.6%) |

| Others (Welayta, Tigrian and Gumez) | 17 (4%) |

| Occupation | |

| Farmer | 183 (42.9%) |

| House wife | 177 (41.5%) |

| Government employee | 28 (6.6%) |

| Others (student, daily laborer, merchant, and private employee) | 39 (9.0%) |

| Husband’s educational status (n = 381) | |

| Unable to read and write | 161 (42.3%) |

| Primary | 111 (29.1%) |

| Secondary | 54 (14.2%) |

| College or University | 55 (14.4%) |

Reproductive characteristics of respondents

Two hundred seventy (60.9%) respondents were experienced first birth before the age of 20. The mean age at first pregnancy was 19.09 years old (SD 3.017). Twenty (4.7%) respondents had history of still birth. Two hundred thirty-eight (55.7%) respondents were Para two, 119 (27.9%) primi-para and the rest grand multipara (5 +). Three hundred fifty-two (82.4%) of respondents had ANC follow up.

Utilization of institutional delivery service

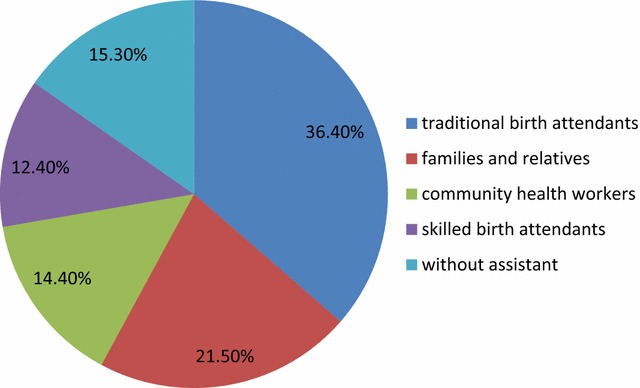

Of the 427 respondents, 218 (51.1%) of them gave birth at health facility. Among women who delivered at health facility, 107 (49.1%) deliveries were in hospital, 77 (35.3%) in health center and 34 (15.6%) in health posts., The common reasons for home delivery were labour was urgent (25.8%), home birth was usual habit for them (24%), health center was too far (19.1%), family influence to deliver at home (14.8%), lack of transportation (9.1%) and no problem at the time of delivery (7.2%). About 15.3% of the home births were delivered without assistant (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percentage distribution of birth attendant for women who gave birth at home in Pawe district, Benishangul Gumez, Ethiopia, March 2015

Factors associated with institutional delivery

Mothers with age group of less than 25 years old were about 3.4 times (AOR = 3.4, 95% CI 1.46, 7.97, p = 0.005) more likely to deliver in health facility than mothers with age group 35 and above. Mothers whose husbands occupation was governmental employee were 5.2 times (AOR = 5.16, 95% CI 1.74, 15.31, p = 0.003) more likely to deliver in health facility than mothers whose husbands were farmer by occupation. Having 4 + frequency of ANC visit in the recent pregnancy were about 3.3 times (AOR = 3.34, 95% CI 1.88, 5.94, p = 0.001) more likely to give birth in health facility when compared to mothers who had less than 4 frequency of ANC visit. Mothers who were knowledgeable on obstetrical danger signs of pregnancy and delivery were about 7.2 times (AOR = 7.18, 95% CI 3.77, 13.66, p = 0.001) more likely to deliver in health facility when compared to mothers who were not knowledgeable (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate and multivariable analysis of factors associated with institutional delivery in Pawe district Benishangul-Gumez, Ethiopia March 2015

| Variable | Institutional delivery (N = 427) | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| Age of the mother | ||||

| 15–24 | 38 | 71 | 3.322 (1.941, 5.684) | 3.412 (1.461, 7.972)* |

| 25–34 | 91 | 102 | 1.993 (1.256, 3.162) | 1.245 (.636, 2.438) |

| ≥ 35 | 80 | 45 | 1 | 1 |

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | 166 | 152 | 1 | 1 |

| Urban | 43 | 66 | 1.676 (1.077, 2.610) | 0.460 (0.176, 1. 201) |

| Mother’s educational status | ||||

| Unable to write and read | 129 | 70 | 1 | 1 |

| Primary education | 65 | 85 | 2.410 (1.560, 3.722) | 1.199 (0.646, 2.223) |

| Secondary and above | 15 | 63 | 7.740 (4.107, 14.588) | 1.233 (0.476, 3.190) |

| Husband’s occupation (N = 381) | ||||

| Farmer | 162 | 124 | 1 | 1 |

| Merchant/private employee | 9 | 23 | 3.339 (1.492, 7.470) | 1.519 (.535, 4.317) |

| Government employee | 10 | 53 | 6.924 (3.387, 14.155) | 5.162 (1.740, 15.310)* |

| Possession of radio or television | ||||

| No | 172 | 128 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 37 | 90 | 3.269 (2.093, 5.105) | 1.575 (0.786, 3.158) |

| Last pregnancy planned? | ||||

| No | 42 | 19 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 167 | 199 | 2.634 (1.475, 4.703) | 1.440 (0.604, 3.432) |

| Time to reach to the nearest HF on walk | ||||

| < 30 | 51 | 85 | 1.980 (1.305, 3.004) | 2.049 (.887, 4.733) |

| ≥ 30 | 158 | 133 | 1 | 1 |

| Frequency of ANC visit | ||||

| < 4 | 79 | 53 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 + | 60 | 160 | 3.975 (2.516, 6.280) | 3.341 (1.879, 5.939)** |

| Knowledge on danger signs | ||||

| No | 120 | 25 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 89 | 193 | 10.409 (6.321, 17.140) | 7.176 (3.770, 13.658)** |

* Significantly associated at p < 0.05

** Significantly associated at p < 0.001

Discussion

According to this study, institutional delivery with skilled birth attendant was 51.1%. This indicates that nearly half of mothers were delivered at home without the help of SBA to rescue the life in emergency situation. The current finding is consistent with the findings reported from SSA, Nepal, East Delhi India, and Ethiopia, where the proportion of mothers who gave birth in health facility were 53, 48, 51, 47 and 48.3% respectively [3, 11, 12, 20, 21]. However, the current prevalence of health facility delivery is higher when compared to reports from districts of Ethiopia, where the proportion of mothers who gave birth at health facility were 15.7, 37.9 and 25% respectively [17, 22, 23]. This discrepancy might be due to the difference in intervention that has been taking place by the midwives, Health extension workers and women development army in auditing and mobilizing pregnant mothers for maternal health service utilization to reach all segments of the population.

On the contrary, the current report is lower when compared to reports from districts of Ethiopia, where 97, 61.6 and 62.2% of mothers gave birth in health facility respectively [24–26]. This could be due to the fact that majority of respondents in this study were rural residents, where as participants of the above studies were urban residents. Hence, they could have better decision making autonomy and better access to information than rural residents.

Respondents in the age group of less than 25 years old were about 3.3 times more likely to give birth in health facility when compared to mothers in the age of 35 and above. This finding is consistent with the reports from districts of Ethiopia, where respondents within the age group of 15–24 years were about 4 times more likely to give birth in health facility as compared to age group of 35 and above respectively [18, 22, 27]. This might be due to the fact that younger mothers are more likely to be educated and they may have a better opportunity to access information as compared to older mothers. Respondents whose husbands occupation were governmental employee were about 5.2 times more likely to give birth at health facility as compared to mothers whose husbands were farmers by occupation. This finding is in line with the findings from Bangladesh and Ethiopia [28, 29]. This might be people working in government organizations usually educated and might have better opportunity to access information and use health services when compared to farmers. Respondents who had 4 + frequency of ANC visit were about 3.3 times more likely to give birth in health facility when compared to mothers with less than four visit. This finding is consistent with many reports from parts of Ethiopia [17, 26]. This might be ANC can provide an opportunity for health workers to promote health facility delivery and to counsel birth preparedness and complication readiness. Moreover, mothers who present for ANC follow up have already demonstrated readiness to use available services. Maternal knowledge on danger signs of obstetrics in pregnancy and delivery was about 7.2 times more likely to give birth in health facility as compared to their counterparts. The current finding is consistent with the reports from Ethiopia (Metekel and Sodo) [26, 30]. This might be due to that respondents who had knowledge on danger signs could have a greater fear of complications, lead them to seek skilled attendance during birth.

Conclusion and recommendation

Although, the prevalence of institutional delivery is high when compared to previous reports from districts of Ethiopia, still institutional delivery is low in the study area. This finding is a clue to modify strategies and programs to close the gaps and improve health service utilization. The interventions that have been taking place by ministry of health to increase health service utilization should be strengthening. Moreover, midwives should strengthen the counseling session regarding pregnancy and delivery danger signs. Midwives should give emphasis in counseling mothers with age group of 25 and above that all pregnancy is at risk of complication and the importance of health facility delivery. Government should give emphasis on strategies that create awareness on farmers to involve in every maternal health care service given for their wives.

Limitations

This study was conducted in one district of Benishangul-Gumez region therefore the findings might not be generalizable to the entire region. The cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow for causality inferences. Despite of these limitations, being a community based study and its sample size adequacy might be taken as strength.

Additional files

Additional file 1. This SPSS template contains that data that support the findings of this study.

Additional file 2. It is an English version questionnaire used to measure this findings and it was developed from different literatures and adjusted contextually by consulting seniors.

Authors’ contributions

AK, SW and MW designed the study. AK prepared the proposal, obtained the data, analyzed and interpreted the data and obtained funding. MW and SW reviewed and commented the entire of the paper from inception to end and involved in the analysis. SW prepared the first draft of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to forward our gratitude to Mekelle University, College of Health Sciences for its support. We would like also to acknowledge Department of Midwifery for its contribution in monitoring this study. Moreover, we thank also the participants of this study, Pawe district health office and Benishangul-Gumez College of Health Sciences for their support and collaboration.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data have been included in the manuscript and it is also the data which supports this findings and questionnaire submitted as Additional files 1 and 2.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from Institutional Ethical Review Board (IERB) of Mekelle University, College of Health Sciences, Ethiopia. A letter of permission was obtained from Metekel zonal Health Office to Pawe district Health Office then to the respective kebeles. Informed signed consent was obtained from study participants after explaining the objective of the study and signed consent for participants below 18 years old was also taken from their fathers/mothers.

Funding

This work has been funded by Mekelle University as for M.Sc. thesis fulfillment and department of midwifery was involved in the project through monitoring and evaluation of the work. But this organization did not involve in designing, analysis, critical review of its intellectual content, and preparation of manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- ANC

antenatal care

- DHS

Demographic and Health Survey

- EDHS

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

- MMR

maternal mortality ratio

- SBAs

skill birth attendants

- SSA

sub Saharan Africa

- TBAs

traditional birth attendants

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13104-018-3295-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Solomon Weldemariam, Email: mikiass1708@gmail.com.

Amare Kiros, Email: amarekiros9@gmail.com.

Mengistu Welday, Email: mengsteab2000@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Trends in maternal mortality: 1990–2013. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank, UN Population Division. Geneva: WHO; 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112682/2/9789241507226_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 27 Jan 2015.

- 2.African progress panel. Maternal health: investing in the lifeline of healthy societies and economies. Africa progress panel policy brief; September 2010.

- 3.Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ICF International . Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey, 2011 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA. Addis Ababa: Central Statistical Agency and ICF International; 2011. p. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang W, Soumya A, Shanxiao W, Alfredo F. Levels and trends in the use of maternal health services in developing countries. DHS comparative reports. 2011 No. 26. Calverton, Maryland, USA: ICF Macro. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/CR26/CR26.pdf. Accessed Dec 2014.

- 5.WHO. Health and the millennium development goals. Geneva: WHO 2005. whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2005/9241562986.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2015.

- 6.Abdella A. Maternal mortality trend in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2010;24(1):115–122. doi: 10.4314/ejhd.v24i1.62953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.USAID maternal health strategy 2014–2020. Ending preventable maternal mortality. Washington; 2014. https://www.usaid.gov. Accessed 29 Jan 2014.

- 8.United Nation. The millennium development goals report. UN, New York; 2013. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/report-2013/mdg-report-2013-english.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2015.

- 9.Fikre A, Demissie M. Prevalence of institutional delivery and associated factors in Dodota Woreda (district), Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2012;9:33. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choulagai B, Onta S, Subed N, et al. Barriers to using skilled birth attendants’ services in mid- and far-western Nepal: a cross sectional study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:49. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-13-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odo BD, Shifti MD. Institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors among child bearing age women in Goba Woreda, Ethiopia. J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;2(4):63–70. doi: 10.11648/j.jgo.20140204.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esena RK, Sappor MM. Factors associated with the utilization of skilled delivery services in the Ga East Municipality of Ghana part 2: barriers to skilled delivery. Int J Sci Technol Res. 2013;2:8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agha S, Carton WT. Determinants of institutional delivery in rural Jhang, Pakistan. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10:31. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-10-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Health sector transformation plan, 2015/16-2019/20. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; October 2015.

- 15.Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey 2014. Ethiopia: Addis Ababa; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Growth and transformation plan II (GTP II) (2015/16-2019/20), Vol 1. National Planning Commission, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; May 2016.

- 17.Hagos S, Shaweno D, Assegid M, Mekonen A, Fantahun MA, Ahmed S. Utilization of institutional delivery service at Wukro and Butajera districts in the Northern and South Central Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:178. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teferra SA, Fekadu M, Alemu MF, Woldeyohannes MS. Institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in the last 12 months in Sekela District, North West of Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gistane A, Maralign T, Behailu M, Worku A, Wondimagegn T. Prevalence and associated factors of home delivery in Arbaminch Zuria district, southern Ethiopia: community based cross sectional study. Sci J Public Health. 2015;3(1):6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anita G, Pragti C, Kannan AT, Gayatri S. Determinants of utilization pattern of antenatal and delivery services in an urbanized village of east Delhi Indian. J Prev Soc Med. 2010;41:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Worku A, Jemal M, Gedefaw A. Institutional delivery service utilization in Woldia, Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2013;1(1):18–23. doi: 10.11648/j.sjph.20130101.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolelie A, Aychiluhm M, Awoke W. Institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors in Banja District, Awie Zone, Amhara Regional Sate, Ethiopia. Open J Epidemiol. 2014;4:30–35. doi: 10.4236/ojepi.2014.41006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asfawosen A, Mussie A, Huruy A, et al. Factors associated with maternal health care services in Enderta District, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Am J Nurs Sci. 2014;3(6):117–125. doi: 10.11648/j.ajns.20140306.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF . Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016: key Indicators Report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA. Addis Ababa: CSA and ICF; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birmeta K, Dibaba Y, Woldeyohannes D. Determinants of maternal health care utilization in Holeta town, central Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:256. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hailemichael F, Woldie M, Tafese F. Predictors of institutional delivery in Sodo town, Southern Ethiopia. Afr J Prm Health Care Fam Med. 2013;5(1):9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amano A, Gebeyehu A, Birhanu Z. Institutional delivery service utilization in Munisa Woreda, South East Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haymanot M, Berhanu D, Agumasie S. Factors affecting choice of delivery place among women in Haramaya Woreda, Oromia Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia. Pharm Innov J. 2013;2:10. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abul B, Kjerstin D, Hans S. Determinants of the use of skilled birth attendants at delivery by pregnant women in Sweden (Master thesis). Umeå University; 2012. https://www.phmed.umu.se/digitalAssets/104/104565_s.m-abul-bashar.pdf. Accessed Nov 2014.

- 30.Gurmesa T, Abebe G. Safe delivery service utilization in Metekel zone, northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2008;17:4. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. This SPSS template contains that data that support the findings of this study.

Additional file 2. It is an English version questionnaire used to measure this findings and it was developed from different literatures and adjusted contextually by consulting seniors.

Data Availability Statement

All data have been included in the manuscript and it is also the data which supports this findings and questionnaire submitted as Additional files 1 and 2.