Abstract

Objective

We assessed associations between physical activity and lung function, and its decline, in the prospective population-based European Community Respiratory Health Survey cohort.

Methods

FEV1 and FVC were measured in 3912 participants at 27–57 years and 39–67 years (mean time between examinations=11.1 years). Physical activity frequency and duration were assessed using questionnaires and used to identify active individuals (physical activity ≥2 times and ≥1 hour per week) at each examination. Adjusted mixed linear regression models assessed associations of regular physical activity with FEV1 and FVC.

Results

Physical activity frequency and duration increased over the study period. In adjusted models, active individuals at the first examination had higher FEV1 (43.6 mL (95% CI 12.0 to 75.1)) and FVC (53.9 mL (95% CI 17.8 to 89.9)) at both examinations than their non-active counterparts. These associations appeared restricted to current smokers. In the whole population, FEV1 and FVC were higher among those who changed from inactive to active during the follow-up (38.0 mL (95% CI 15.8 to 60.3) and 54.2 mL (95% CI 25.1 to 83.3), respectively) and who were consistently active, compared with those consistently non-active. No associations were found for lung function decline.

Conclusion

Leisure-time vigorous physical activity was associated with higher FEV1 and FVC over a 10-year period among current smokers, but not with FEV1 and FVC decline.

Keywords: adults, cohort, forced expiratory volume in one second, forced vital capacity, physical activity, smoking

Key messages.

What is the key question?

Is physical activity associated with higher lung function and reduced lung function decline over a 10-year period among European adults?

What is the bottom line?

Leisure-time vigorous physical activity was associated with higher maximum FEV1and FVC over a 10-year period among current smokers, but not with reduced decline in these lung function parameters.

Why read on?

This study, which is based on data collected over a 10-year period as part of the prospective European ECRHS cohort, strengthens the epidemiological evidence supporting a positive association between physical activity and respiratory health in smokers.

Introduction

Low lung function is an important phenotypic trait of COPD, a condition responsible for nearly 64 million disability-adjusted life-years lost globally.1 Lung function naturally declines with age, and this decline is known to be modified by only a few factors (eg, tobacco smoking,2 mould exposure3 and α1-antitrypsin levels4). The confirmed identification of physical activity as a common modifiable factor able to attenuate age-related lung function decline could lead to significant public health benefits.

Physical inactivity is a leading risk factor for global mortality5 and is strongly linked to several major non-communicable diseases.6 Interestingly, the evidence for a link with respiratory health is weaker, possibly as most previous studies were cross-sectional and thus subject to reverse causation, or because they focused on specific populations (eg, athletes, patients with COPD). The few existing prospective studies suggest a beneficial link between physical activity and respiratory health, although results are inconsistent in terms of subgroups affected and indicators of physical activity.7–12 Some of these inconsistencies could be due to selection bias (eg, use of a convenience sample9), lack of confounder adjustment (eg, socioeconomic status) or because changes in physical activity levels over time were not considered.13 One study on over 6000 adults living in Copenhagen, Denmark, adequately assessed these factors and reported that higher physical activity was associated with less lung function decline and a lower COPD risk in active smokers only.10 11 This observation has not yet been replicated.

The European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) is a three-phase, longitudinal, multicentre study that collected detailed information on environmental, lifestyle and respiratory health factors from adults living across Europe.14 We used this rich data source to assess whether vigorous physical activity is associated with higher maximum FEV1 and FVC, and a reduced rate of FEV1 and FVC decline, in 3912 adults from 25 centres in 11 countries. Further, we tested the hypothesis that this relationship may be stronger among active smokers.10

Methods

Study population

The ECRHS was initiated in 1991–1993 (ECRHS I), when over 18 000 young adults (20–44 years-old) were randomly recruited from available population-based registers (population-based arm), with an oversampling of asthmatics (symptomatic arm). Two examinations (at 27–57 years (ECRHS II, 1999–2003) and 39–67 years (ECRHS III, 2010–2014)) have since taken place. Details of the study design are available.15 16 The current analysis uses data collected during ECRHS II and III, hereon referred to as the first and second examinations. A total of 3912 participants (25 centres in 11 countries) had information on lung function at both time points, physical activity at the first follow-up and base covariates (sex, age, height and smoking), and are therefore included in the present study. We analysed data from both the population-based and symptomatic arms of the ECRHS as our aim was to examine associations with physical activity and not to estimate incidence rates or prevalences in a representative population.17 A flow chart is provided in online supplementary figure S1. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

thoraxjnl-2017-210947supp001.pdf (827.7KB, pdf)

Lung function

Lung function was assessed using different spirometers across centres at the first examination, whereas nearly all centres used the same spirometer at the second examination (online supplementary table S1). For both time points, FEV1 and FVC, repeatable to 150 mL from at least two of a maximum of five correct manoeuvres that met the American Thoracic Society recommendations,18 were used as the primary outcomes. The FEV1/FVC ratio was considered as a secondary outcome. COPD incidence was not considered as an outcome due to an insufficient number of cases. All lung function measures were taken prebronchodilation.

Vigorous physical activity

Leisure-time vigorous physical activity was estimated by asking participants how often (frequency) and for how many hours per week (duration) they usually exercised so much that they got out of breath or sweaty,19 using previously validated questions.20 21 The responses for frequency were every day, 4–6 times a week, 2–3 times a week, once a week, once a month, less than once a month and never. For statistical analyses, we grouped together the first two categories, the next two categories and the last three categories. The responses for duration were 7 hours or more, about 4–6 hours, about 2–3 hours, about 1 hour, about half an hour and none. For statistical analyses, we grouped together the first two categories, the next two categories and the last two categories. At each time point, individuals were categorised as being active if they exercised with a frequency of two or more times a week (‘2–3 times a week’ or greater) and with a duration of about 1 hour a week or more, and non-active otherwise (as done previously in the ECRHS22 and by others23). Change in activity status was categorised into four groups: non-active at both examinations, became inactive, became active and active at both examinations.

Other relevant characteristics

Data on sociodemographic and clinical factors, and other lung function risk factors, were collected using questionnaires. These included sex, age, smoking status (never smoker; ex-smoker with <15 pack-years; ex-smoker with ≥15 pack-years; current smoker with <15 pack-years; current smoker with ≥15 pack-years or more), second-hand smoke exposure (yes; no), age completed full-time education (<17 years; 17–20 years; >20 years), occupation (management/professional/non-manual; technical/professional/non-manual; other non-manual; skilled manual; semiskilled/unskilled manual; other/unknown, classified according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations-88 code24), asthma (yes; no) and report of a comorbidity associated with inflammation with a potential influence on physical activity (yes: arthritis/hypertension/heart disease/diabetes/cancer/stroke; no: none of these). Height and weight were measured.

Statistical analysis

Associations between the physical activity and lung function metrics were estimated using multivariable mixed linear regression models with random intercepts for subjects nested within centres (lme4 package25 in the statistical program R, V.3.3.026). Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Two modelling approaches were performed. First, to assess the prospective impact of physical activity on lung function over a 10-year period, associations between physical activity frequency, duration and activity status assessed at the first examination with lung function assessed at both examinations were examined. An interaction term between the physical activity parameter and time between examinations was included to capture the effect of the physical activity parameter on the rate of lung function decline. The following variables were entered as covariates: sex, age, age-squared (to account for the non-linear relationship between lung function and age27), education, occupation (both entered as the value assessed at the first examination), height, weight, smoking status and second-hand smoke exposure (all entered as the values assessed at the two different examinations). Numeric variables were centred (over the data from both examinations) before modelling.

Second, to assess the impact of changes in physical activity on lung function, associations between changes in activity status between the two examinations and lung function at the second examination were modelled. The same confounders were included, but all were entered as the value assessed at the first examination to control for variation at the beginning of the study. Numeric variables were centred over the data at the first examination. To account for potential ‘regression to the mean’ effects,28 the models were additionally adjusted for lung function at the first examination.

To assess effect modification, the primary models for FEV1 and FVC were stratified by sex, median age of the study sample, smoking status (never, former, current), body mass index (BMI: <25 kg/m2; 25–30 kg/m2; >30 kg/m2), asthma and report of a comorbidity (latter data only available for 19 out of 25 centres), as assessed at the first examination. Models stratified by smoking status were adjusted for lifetime pack-years smoked (not applicable for never smokers).

We performed several sensitivity analyses. Asthmatics, those with current respiratory symptoms (wheezing and whistling in the chest or woken up with a feeling of tightness, shortness of breath or by an attack of coughing, all in the last 12 months), those with COPD (FEV1/FVC less than the lower limit of the normal predicted using the Global Lung Initiative equations29), those avoiding vigorous exercise because of wheezing or asthma, and those who took inhaled medication to help breathing in the last 12 months, all assessed at the first examination, were excluded in separate analyses. We also examined the impact of excluding those from the symptomatic ECRHS study arm and those with lung function changes greater than 100 mL/year. In a further sensitivity analysis, BMI was included in the model instead of weight. We also removed lung function at first examination as an adjustment variable in the second modelling approach, as has been suggested.30 Finally, we adjusted all models for lung function at ECRHS baseline (measured 10 years prior to the collection of the physical activity data) to more completely assess potential reverse causation.

Results

Study characteristics

Compared with those with information at the first examination (n=7518), individuals included in this analysis were slightly older and less likely to smoke, be exposed to second-hand smoke and report asthma. However, they were more likely to have higher FEV1 values at the first examination, higher education and work in a managerial position. Descriptive statistics of the study population are presented in tables 1 and 2. FEV1 at the second examination was significantly lower among current smokers compared with never smokers, as identified at the first examination (mean FEV1 was 2951 mL and 3058 mL among current and never smokers, respectively; Student’s t-test P value <0.001). In addition, declines of both FEV1 and FVC were significantly greater among current smokers than never smokers (FEV1 declines were −46.9 mL/year and −40.4 mL/year among current and never smokers, respectively; Student’s t-test P value <0.001; and FVC declines were −36.8 mL/year and −32.3 mL/year among current and never smokers, respectively; Student’s t-test P value=0.004). Men (27.9%) and non-asthmatics (25.6%) were more likely to be current smokers than women (22.4%) and asthmatics (22.2%). Vigorous physical activity frequency and duration, as well as the percentage of individuals considered active, increased over the 10-year follow-up period (table 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population

| Characteristics | First examination | Second examination | ||

| n/N or mean | % or (SD) | n/N or mean | % or (SD) | |

| Male sex | 1908/3912 | 48.8 | – | – |

| Symptomatic study arm of ECRHS cohort | 550/3912 | 14.1 | – | – |

| Age completed full-time education | ||||

| <17 years | 689/3893 | 17.7 | – | – |

| 17–20 years | 1367/3893 | 35.1 | – | – |

| >20 years | 1837/3893 | 47.2 | – | – |

| Age in years (mean (SD)) | 43.2 | (7.1) | 54.3 | (7.1) |

| Height in cm (mean (SD)) | 170.4 | (9.6) | 169.8 | (9.6) |

| Weight in kg (mean (SD)) | 74.4 | (15.2) | 78.3 | (16.1) |

| BMI | ||||

| Continuous, in kg/m2 (mean (SD)) | 25.5 | (4.3) | 27.1 | (4.8) |

| <25 kg/m2 | 1980/3894 | 50.8 | 1414/3891 | 36.3 |

| 25–30 kg/m2 | 1399/3894 | 35.9 | 1575/3891 | 40.5 |

| >30 kg/m2 | 515/3894 | 13.2 | 902/3891 | 23.2 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never | 1793/3912 | 45.8 | 1718/3616 | 47.5 |

| Ex-smoker with <15 pack-years | 747/3912 | 19.1 | 716/3616 | 19.8 |

| Ex-smoker with ≥15 pack-years | 392/3912 | 10.0 | 586/3616 | 16.2 |

| Current smoker with <15 pack-years | 395/3912 | 10.1 | 140/3616 | 3.9 |

| Current smoker with ≥15 pack-years | 585/3912 | 15.0 | 456/3616 | 12.6 |

| Second-hand smoke exposure at home or work | 1423/3893 | 36.6 | 727/3891 | 18.7 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Management/professional/non-manual | 1204/3912 | 30.8 | 1352/3912 | 34.6 |

| Technical/professional/non-manual | 717/3912 | 18.3 | 736/3912 | 18.8 |

| Other non-manual | 989/3912 | 25.3 | 856/3912 | 21.9 |

| Skilled manual | 394/3912 | 10.1 | 313/3912 | 8.0 |

| Semiskilled/unskilled manual | 360/3912 | 9.2 | 355/3912 | 9.1 |

| Other/unknown | 248/3912 | 6.3 | 300/3912 | 7.7 |

| Asthma | 613/3907 | 15.7 | 735/3901 | 18.8 |

| COPD* | 213/3781 | 5.6 | 356/3788 | 9.4 |

| Comorbidity† | 573/2651 | 21.6 | 1487/3863 | 38.5 |

*Defined as FEV1/FVC less than the lower limit of normal predicted using the Global Lung Initiative equations.29

†Report of either arthritis, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, cancer and stroke. Only available for 19 out of 25 participating centres at the first examination. All centres collected this information at the second examination.

BMI, body mass index; ECRHS, European Community Respiratory Health Survey; n, number of cases; N, total available sample size.

Table 2.

Distribution of measured lung function values by characteristics assessed at the first examination

| FEV1 | FVC | |||||||||||

| First examination (1999–2003) (mL) |

Second examination (2010–2014) (mL) |

Difference between examinations* (mL/year) | First examination (1999–2003) (mL) |

Second examination (2010–2014) (mL) |

Differences between examinations* (mL/year) | |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Whole population | 3510 | 797 | 3028 | 756 | −43.0 | 26.4 | 4377 | 984 | 3992 | 953 | −34.3 | 34.1 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 4047 | 694 | 3519 | 679 | −47.5 | 29.9 | 5088 | 804 | 4660 | 807 | −38.9 | 38.2 |

| Female | 3000 | 496 | 2566 | 486 | −38.8 | 21.9 | 3703 | 582 | 3366 | 583 | −30.1 | 29.2 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||||

| Never | 3513 | 814 | 3058 | 772 | −40.4 | 25.5 | 4347 | 1011 | 3984 | 980 | −32.3 | 33.5 |

| Ex-smoker | 3533 | 803 | 3047 | 753 | −43.6 | 26.4 | 4432 | 980 | 4035 | 956 | −36.3 | 34.7 |

| Current smoker | 3480 | 772 | 2951 | 724 | −46.9 | 27.9 | 4364 | 952 | 3954 | 900 | −36.8 | 35.6 |

| Diseases | ||||||||||||

| None | 3612 | 781 | 3148 | 748 | −41.5 | 24.7 | 4435 | 978 | 4089 | 955 | −30.7 | 33.4 |

| Asthma | 3207 | 799 | 2761 | 772 | −39.0 | 28.9 | 4189 | 1000 | 3803 | 976 | −34.4 | 35.9 |

| COPD† | 2853 | 768 | 2478 | 784 | −33.4 | 33.5 | 4371 | 1093 | 3883 | 1098 | −42.9 | 43.2 |

| Comorbidity‡ | 3315 | 783 | 2824 | 754 | −43.1 | 26.3 | 4170 | 951 | 3750 | 947 | −38.0 | 32.9 |

*Lung function at the second examination (2010–2014) minus that at the first examination (1999–2003), divided by time between the examinations. The means of the lung function parameters were significantly different across the two examinations for all lung function parameters (Student’s t-test for paired data, all P values <0.001).

†Defined as FEV1/FVC less than the lower limit of normal predicted using the Global Lung Initiative equations.29

‡Report of either arthritis, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, cancer and stroke. Only available for 19 out of 25 participating centres.

Table 3.

Distribution of vigorous physical activity variables*

| First examination (1999–2003) |

Second examination (2010–2014) |

|||

| n/N | % | n/N | % | |

| Frequency | ||||

| ≤1 a month | 1559/3910 | 39.9 | 1499/3896 | 38.5 |

| 1–3 times a week | 1833/3910 | 46.9 | 1736/3896 | 44.6 |

| ≥4 times a week | 518/3910 | 13.2 | 661/3896 | 17.0 |

| Duration | ||||

| ≤30 min | 1595/3880 | 41.1 | 1559/3845 | 40.5 |

| 1–3 hours | 1675/3880 | 43.2 | 1514/3845 | 39.4 |

| ≥4 hours | 610/3880 | 15.7 | 772/3845 | 20.1 |

| Active | ||||

| ≥2 times a week and ≥1 hour | 1450/3878 | 37.4 | 1635/3843 | 42.5 |

| Changes between first (1999–2003) and second (2010–2014) examinations | ||||

| Inactive at both examinations | 1637/3816 | 42.9 | ||

| Active at first examination but inactive at second examination | 551/3816 | 14.4 | ||

| Inactive at first examination but active at second examination | 752/3816 | 19.7 | ||

| Active at both examinations | 876/3816 | 23.0 | ||

*There was a significant change in the distributions of all physical activity parameters (frequency, duration and active status) across the two examinations (McNemar-Bowker test, all P values <0.001).

n, number of cases; N, total available sample size.

Associations between vigorous physical activity levels and lung function measurements

Active individuals at the first examination had higher FEV1 and FVC on average at both examinations than their non-active counterparts (table 4 for the results for the physical activity parameters, and online supplementary tables S2 and S3 for the results for all other covariates). There was no independent association between physical activity and the rate of FEV1 or FVC decline (table 4). The mean FVC was positively associated with frequency and duration of physical activity (table 4), whereas the mean FEV1/FVC ratio appeared negatively associated with both of these factors (online supplementary table S4).

Table 4.

Associations between vigorous physical activity variables at the first examination and lung function and decline*

| Vigorous physical activity levels | N | FEV1 (mL) | FVC (mL) | |||

| Mean difference | 95% CI | N | Mean difference | 95% CI | ||

| Association with lung function† | ||||||

| Frequency | ||||||

| ≤1 a month | 3887 | Reference | 3872 | Reference | ||

| 1–3 times a week | 13.2 | −20.3 to 46.6 | 16.9 | −21.2 to 55.1 | ||

| ≥4 times a week | 12.3 | −35.9 to 60.4 | 59.3 | 4.4 to 114.3 | ||

| Duration (per week) | ||||||

| ≤30 min | 3857 | Reference | 3842 | Reference | ||

| 1–3 hours | 20.8 | −13.2 to 54.8 | 13.5 | −25.3 to 52.3 | ||

| ≥4 hours | 39.3 | −5.9 to 84.6 | 73.9 | 22.4 to 125.4 | ||

| Active | ||||||

| ≥2 times and ≥1 hour per week | 3855 | 43.6 | 12.0 to 75.1 | 3840 | 53.9 | 17.8 to 89.9 |

| Association with rate of lung function decline‡ | ||||||

| Frequency | ||||||

| ≤1 a month | 3887 | Reference | 3872 | Reference | ||

| 1–3 times a week | 1.6 | −0.3 to 3.4 | 0.1 | −2.2 to 2.5 | ||

| ≥4 times a week | −0.3 | −2.9 to 2.4 | −1.5 | −4.9 to 2.0 | ||

| Duration (per week) | ||||||

| ≤30 min | 3857 | Reference | 3842 | Reference | ||

| 1–3 hours | 2.3 | 0.4 to 4.1 | 1.7 | −0.7 to 4.1 | ||

| ≥4 hours | 1.4 | −1.1 to 3.9 | 1.9 | −1.4 to 5.1 | ||

| Active | ||||||

| ≥2 times and ≥1 hour per week | 3855 | 1.4 | −0.3 to 3.2 | 3840 | −0.3 | −2.6 to 2.0 |

Bold indicates P value <0.05.

*Adjusted for sex, age, age-squared, height, weight, smoking status, second-hand smoke exposure, education and occupation. An interaction term between time between follow-ups and the physical activity parameter was included to capture the effect of physical activity on lung function decline.

†A positive estimate suggests that those more active at the first examination had higher average lung function at both examinations than those less active.

‡A positive estimate suggests that those more active at the first examination had a smaller decline in lung function between the two examinations than those less active.

N, number of participants included in the model.

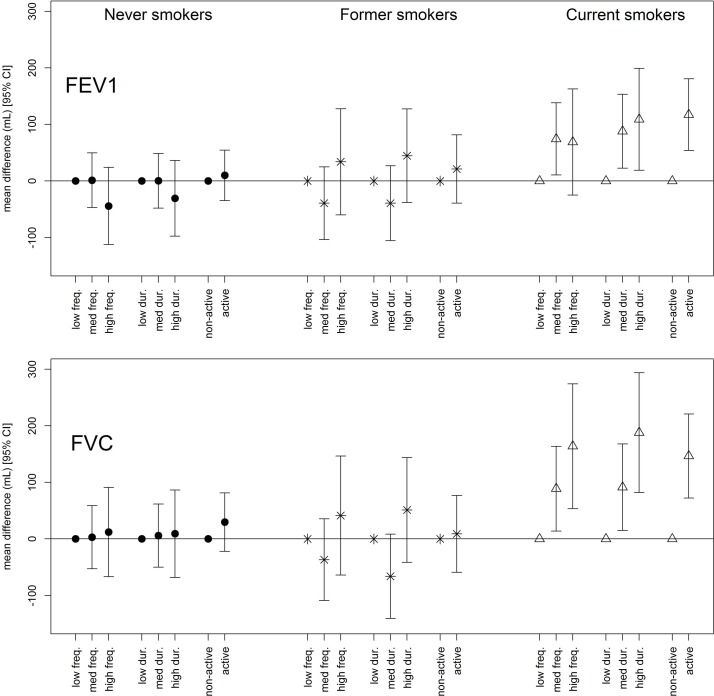

Stratification by smoking status revealed that the associations with FEV1 and FVC were only apparent among current smokers (figure 1; effect estimates and model sample sizes for FEV1 and FVC are presented in online supplementary tables S5 and S6, respectively). Associations stratified by asthma (online supplementary figure S2), comorbidities (online supplementary figure S3) and age (online supplementary figure S4) were driven by the current smokers in each of the respective groups. Removing participants with current respiratory symptoms (48.3%) led to the attenuation of the associations.

Figure 1.

Associations between vigorous physical activity variables at the first examination and lung function, stratified by smoking behaviour. All models are adjusted for sex, age, age-squared, height, weight, second-hand smoke exposure, education, occupation and lifetime pack-years smoked. Filled circles=never smokers; stars=former smokers; open triangles=current smokers. For frequency (freq.), low: ≤1 a month; med: 1–3 times a week; high: ≥4 times a week. For duration (dur.), low: ≤30 min; med: 1–3 hours; high: ≥4 hours. Active, ≥2 times and ≥1 hour per week.

Associations appeared stronger for men than for women (online supplementary table S7), whereas those stratified by BMI did not reveal a consistent pattern (online supplementary tables S8 and S9 for FEV1 and FVC, respectively). Adjusting the models for BMI instead of weight, as well as excluding those with COPD, those avoiding vigorous exercise because of wheezing or asthma or those taking inhalation medication to help breathing in the last 12 months did not alter the general conclusions (not shown). Further, excluding the ECRHS symptomatic study arm or those with FEV1 and FVC declines greater than 100 mL/year also did not affect the results (not shown). Adjusting the models for lung function at ECRHS baseline (assessed 10 years prior to the collection of the physical activity data) did attenuate the effect estimates, although this may be the result of an overadjustment of the models (online supplementary table S10).

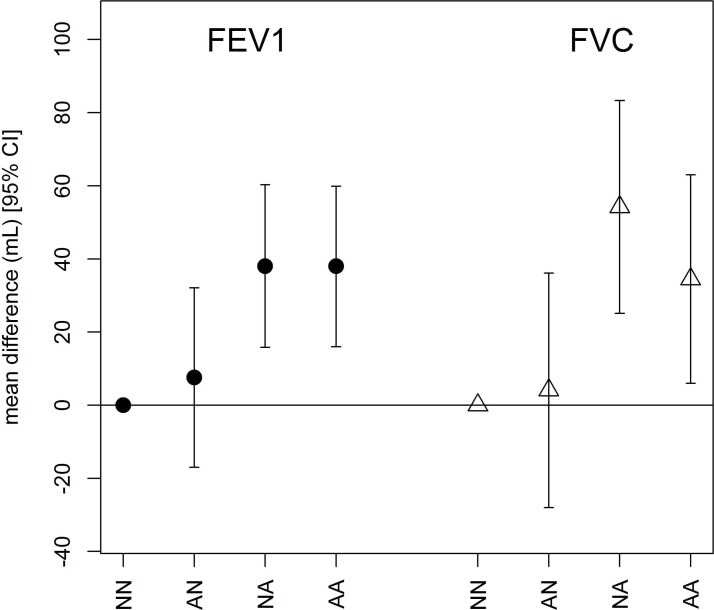

Change in vigorous physical activity and lung function at the second examination

With respect to subjects who were non-active at both occasions, subjects who became or remained active during the follow-up period had higher FEV1 and FVC at the second examination (figure 2). Results were similar both with and without adjustment for lung function at the first examination, as well as with adjustment for lung function at ECRHS baseline (online supplementary table S10). None of the sensitivity analyses conducted greatly affected these associations.

Figure 2.

Associations between change in vigorous physical activity status between the first and second examinations and lung function at the second examination. All models are adjusted for sex, age, age-squared, height, weight, smoking status, second-hand smoke exposure, education and occupation. AA, active at both examinations; AN, active at the first examination but not at the second; NA, non-active at the first examination but active at the second; NN, non-active at both examinations.

Discussion

From this work, we can draw four conclusions: (1) Leisure-time vigorous physical activity seems to be associated with higher FEV1 and FVC. (2) These associations were only apparent among current smokers. (3) There was no indication that vigorous physical activity attenuated the rate of FEV1 and FVC decline in this age group. (4) Increasing physical activity from non-active to active during the follow-up was associated with higher FEV1 and FVC.

Interpretation

There are three potential mechanisms to explain an association between physical activity and lung function. First, it is increasingly accepted that regular physical activity has long-term systemic anti-inflammatory effects that can be mediated through the induction of an anti-inflammatory environment within the body.31 Our results are in line with this explanation as associations were only apparent among current smokers (a population subgroup with a high inflammatory burden), an observation that has been reported by some10 but not all8 previous epidemiological studies. Associations simultaneously stratified by disease status (asthma, comorbidity) and smoking status, as well as by age group and smoking status, revealed that associations were largely seen among the current smokers in all groups. A higher proportion of current smokers was also apparent among men, which may explain why associations appeared slightly stronger for this group compared with women. Future studies that link physical activity to improved lung function using biological markers of systemic inflammation are needed to more fully explore anti-inflammation as a potential mechanism.

Notably, we did not observe consistent associations between physical activity and lung function among asthmatics, another high-inflammation group. This result is in contrast to a recent study in which there appeared to be less decline in FEV1, FEV1/FVC and peak expiratory flow among physically active asthmatics compared with non-active asthmatics.12 The fact that asthmatics and other sick populations are challenging to analyse as they may limit their physical activity due to various reasons, such as physical activity-induced respiratory symptoms, may explain the inconsistency between the results of the current study and previous ones.

A second pathway by which increased physical activity may lead to higher lung function is via beneficial changes in body composition and fat distribution, which can affect lung mechanics32 and be linked to low-grade systemic inflammation.31 Our effect estimates were robust to adjustments for weight and BMI, possibly indicating that other pathways may be more important in this population. However, we were somewhat limited in our ability to look at associations in highly obese participants (>35 kg/m2) due to sample size constraints. Given that regular physical activity protects against obesity33 and that a high BMI reduces measured lung volumes,34 we hesitate to completely exclude changes in weight/BMI as a potential pathway by which physical activity may affect lung function. It is more likely that this relationship is complex and dependent on the interaction of several factors, as demonstrated in Chinn et al,35 where the authors reported that the beneficial effects of smoking cessation on lung function were attenuated by subsequent weight gain.35

A final pathway may be that physical activity improves respiratory muscle endurance and strength,36 37 which could correspond to a short-term/moderate-term effect that requires sustained physical effort to maintain it. This hypothesis remains to be adequately tested as we were not able to do so given our available data. Nonetheless, the existence of a short-term/medium-term mechanistic effect is consistent with our investigation of how changes in physical activity affected lung function, as only participants who were active at the last examination (either by becoming or remaining active) had significantly higher lung function than those consistently inactive.

We also observed that increased physical activity appeared to be associated with a lower mean FEV1/FVC ratio at both examinations. This result should be interpreted with substantial caution as it is likely to be driven by the apparent larger size of the association between physical activity on FVC compared with FEV1, which would lower the FEV1/FVC ratio among active individuals.

Finally, in our analysis, we found no associations between the physical activity indicators and the rate of lung function decline over the 10-year study period. Two studies that previously reported an association between physical activity and the amount or rate of FEV1 decline had a relatively short follow-up period (3.7 years7 and 5 years9), whereas others with longer follow-ups found associations with lung function decline in subgroups only (current smokers,10 older Finnish men8 and asthmatics11). It is possible that differences in the physical activity assessment and the populations studied may have led to the inconsistencies in the results. For example, in the study that reported associations between physical activity and lung function decline after 10 years in current smokers,10 the physical activity assessment included measures of light to vigorous physical activity during leisure time and work, whereas in the current analysis only data on leisure-time vigorous physical activity were available. It is possible that moderate physical activity is more relevant for achieving long-term reductions in lung function decline. Furthermore, no study has yet considered the impact of sedentary time on lung function decline, although sedentary behaviour can set off a low level but chronic proinflammatory response.38 Future studies with additional follow-ups (and shorter time gaps) and which include objective measures of various types and intensities of physical activity are needed to better understand these findings. Finally, random variability in the measurement of lung function (and consequently its changes over time) might have attenuated our ability to detect associations between physical activity and lung function decline.

Strengths and limitations

Our results may be subject to selection bias as participants were more likely to have a high socioeconomic status (education, occupation) and a higher FEV1 at the first examination than those who did not participate in the second examination. Although we were able to account for most known confounders, residual confounding may be a concern as we did not consider the effect of diet, as data on dietary total energy intake were only available for a subset of the study population and only at the second examination. We also did not consider the potential for time-dependent confounding to affect our results, as this type of confounding was shown to not largely affect associations between physical activity and lung function in a similar study.11 We evaluated the impact of information bias by excluding asthmatics, those with current respiratory symptoms, those reporting avoiding vigorous exercise because of wheezing/asthma and the ECRHS symptomatic study arm in separate sensitivity analyses. However, as consistent associations were only found with lung function levels (and not lung function decline), our results are cross-sectional in nature and hence subject to potential reverse causation.

The use of questionnaires to collect physical activity information is an important limitation of this study. It was not possible to collect more detailed information using personal measures in a study of this size, geographical distribution and with such a long follow-up. Any imprecision in the self-assessment of physical activity by questionnaire, and also in the measurement of repeated lung function, would likely lead to non-differential misclassification, which would attenuate the results. Hence, physical activity exposure misclassification as well as random variability in the lung function measurements, and their calculated differences over time, may be potential reasons for why we do not see associations with lung function decline. Further, as aforementioned, we only had data to estimate vigorous physical activity during leisure time,19 and it is possible that different physical activity intensities may yield different health effects.39 All analyses were adjusted for occupation as an indicator of occupation-related physical activity, although this measure is certainly suboptimal. We were also unable to directly compare the physical activity categories used in this analysis with the current WHO recommendations for physical activity in adults.40 Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that associations were most robust for the ‘active status’ variable, potentially suggesting that a combination of a certain minimum physical activity frequency and duration is required to achieve optimal health benefits.

Lung function measurements were made according to published recommendations and quality control procedures were followed. The spirometry devices were updated between examinations, which could have led to inherent temporal differences in lung function that may differ by age and height.41 Our results remained unchanged after replication with a set of lung function values corrected for change in spirometer, following a similar methodology as previously described for another adult cohort.41 Further strengths include the large sample size, population-based nature of ECRHS and broad geographical representation of participants.

In conclusion, a beneficial link between increased leisure-time vigorous physical activity and higher lung function was observed in this European prospective population-based study. Associations were only apparent among current smokers, which supports the existence of an inflammation-related biological mechanism and highlights the importance of physical activity in this group at higher risk (due to smoking) for poor lung function. No association between vigorous physical activity and lung function decline was observed, a result that requires further investigation.

Footnotes

Contributors: EF, A-EC and JGA designed the study. EF wrote the initial draft, conducted the statistical analyses and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors provided substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work, revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the final version, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship scheme (Elaine Fuertes, H2020- MSCA-IF-2015; proposal number 704268). The present analyses are part of the Ageing Lungs in European Cohorts (ALEC) Study (www.alecstudy.org), which has also received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no 633212. The local investigators and funding agencies for the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS II and ECRHS III) are reported in the online supplementary file. These funders did not have any role in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: PD reports consulting fees from ALK, Stallergènes Greer, Circassia, Chiesi, Thermofisher Scientific and Ménarini, and AGC reports grants from Chiesi Farmaceutici and from GlaxoSmithKline Italy, during the conduct of the study. Other authors declare no competing interests related to this work.

Ethics approval: Each participating center obtained ethical approval from their local ethics committees and followed the rules for ethics and data protection from their country, which were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Author note: ISGlobal is a member of CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya.

Presented at: Some of the results were presented in the form of an oral presentation at the 2016 European Respiratory Society International Congress.

References

- 1. Kassebaum N. GBD 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1603–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31460-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Murray RP. Smoking and lung function of Lung Health Study participants after 11 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:675–9. 10.1164/rccm.2112096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Norbäck D, Zock JP, Plana E, et al. Lung function decline in relation to mould and dampness in the home: the longitudinal European Community Respiratory Health Survey ECRHS II. Thorax 2011;66:396–401. 10.1136/thx.2010.146613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sandford AJ, Chagani T, Weir TD, et al. Susceptibility genes for rapid decline of lung function in the lung health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:469–73. 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2006158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization. Physical activity [Internet]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs385/en/

- 6. Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012;380:219–29. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jakes RW, Day NE, Patel B, et al. Physical inactivity is associated with lower forced expiratory volume in 1 second: European prospective investigation into cancer-norfolk prospective population study. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156:139–47. 10.1093/aje/kwf021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pelkonen M, Notkola I-L, Lakka T, et al. Delaying decline in pulmonary function with physical activity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:494–9. 10.1164/rccm.200208-954OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheng YJ, Macera CA, Addy CL, et al. Effects of physical activity on exercise tests and respiratory function. Br J Sports Med 2003;37:521–8. 10.1136/bjsm.37.6.521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Benet M, et al. Regular physical activity modifies smoking-related lung function decline and reduces risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:458–63. 10.1164/rccm.200607-896OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Serra I, et al. Time-dependent confounding in the study of the effects of regular physical activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an application of the marginal structural model. Ann Epidemiol 2008;18:775–83. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brumpton BM, Langhammer A, Henriksen AH, et al. Physical activity and lung function decline in adults with asthma: The HUNT Study. Respirology 2017;22:278–83. 10.1111/resp.12884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Watz H, Pitta F, Rochester CL, et al. An official European Respiratory Society statement on physical activity in COPD. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1521–37. 10.1183/09031936.00046814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Janson C, Anto J, Burney P, et al. The European Community Respiratory Health Survey: what are the main results so far? Eur Respir J 2001;18:598–611. 10.1183/09031936.01.00205801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burney PG, Luczynska C, Chinn S, et al. The European community respiratory health survey. Eur Respir J 1994;7:954–60. 10.1183/09031936.94.07050954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. European Community Respiratory Health Survey II Steering Committee. The European Community Respiratory Health Survey II. Eur Respir J 2002;20:1071–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rothman KJ, Gallacher JE, Hatch EE. Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1012–4. 10.1093/ije/dys223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–38. 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet | Physical Activity and Health. What is Moderate-intensity and Vigorous-intensity Physical Activity? [Internet]. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/physical_activity_intensity/en

- 20. Rovio S, Kåreholt I, Helkala EL, et al. Leisure-time physical activity at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol 2005;4:705–11. 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70198-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Washburn RA, Goldfield SR, Smith KW, et al. The validity of self-reported exercise-induced sweating as a measure of physical activity. Am J Epidemiol 1990;132:107–13. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shaaban R, Leynaert B, Soussan D, et al. Physical activity and bronchial hyperresponsiveness: European Community Respiratory Health Survey II. Thorax 2007;62:403–10. 10.1136/thx.2006.068205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Booth ML, Okely AD, Chey T, et al. The reliability and validity of the physical activity questions in the WHO health behaviour in schoolchildren (HBSC) survey: a population study. Br J Sports Med 2001;35:263–7. 10.1136/bjsm.35.4.263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Office IL I. International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-88). Geneva: International Labour Organisation, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, et al. Lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R package version 1.1-6. www.CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4.

- 26. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2012. ISBN 3-900051-07-0 http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kerstjens HA, Rijcken B, Schouten JP, et al. Decline of FEV1 by age and smoking status: facts, figures, and fallacies. Thorax 1997;52:820–7. 10.1136/thx.52.9.820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:215–20. 10.1093/ije/dyh299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 2012;40:1324–43. 10.1183/09031936.00080312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marcon A, Accordini S, de Marco R. Adjustment for baseline value in the analysis of change in FEV1 over time. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;124:1120 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gleeson M, Bishop NC, Stensel DJ, et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011;11:607–15. 10.1038/nri3041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Salome CM, King GG, Berend N. Physiology of obesity and effects on lung function. J Appl Physiol 2010;108:206–11. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00694.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wadden TA, Webb VL, Moran CH, et al. Lifestyle modification for obesity: new developments in diet, physical activity, and behavior therapy. Circulation 2012;125:1157–70. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.039453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jones RL, Nzekwu MM. The effects of body mass index on lung volumes. Chest 2006;130:827–33. 10.1378/chest.130.3.827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chinn S, Jarvis D, Melotti R, et al. Smoking cessation, lung function, and weight gain: a follow-up study. Lancet 2005;365:1629–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66511-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Paul LE, Kronmal RA, Manolio TA, et al. Respiratory muscle strength in the elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;149:430–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen HI, Kuo CS. Relationship between respiratory muscle function and age, sex, and other factors. J Appl Physiol 1989;66:943–8. 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.2.943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. The role of exercise and PGC1alpha in inflammation and chronic disease. Nature 2008;454:463–9. 10.1038/nature07206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Donaire-Gonzalez D, Gimeno-Santos E, Balcells E, et al. Benefits of physical activity on COPD hospitalisation depend on intensity. Eur Respir J 2015;46:1281–9. 10.1183/13993003.01699-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. World Health Organization. Physical activity and Adults [Internet]. www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_adults/en/

- 41. Bridevaux PO, Dupuis-Lozeron E, Schindler C, et al. Spirometer replacement and serial lung function measurements in population studies: results from the SAPALDIA Study. Am J Epidemiol 2015;181:752–61. 10.1093/aje/kwu352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

thoraxjnl-2017-210947supp001.pdf (827.7KB, pdf)