Abstract

Summary

GLINT is a user-friendly command-line toolset for fast analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation data generated using the Illumina human methylation arrays. GLINT, which does not require any programming proficiency, allows an easy execution of Epigenome-Wide Association Study analysis pipeline under different models while accounting for known confounders in methylation data.

Availability and Implementation

GLINT is a command-line software, freely available at https://github.com/cozygene/glint/releases. It requires Python 2.7 and several freely available Python packages. Further information and documentation as well as a quick start tutorial are available at http://glint-epigenetics.readthedocs.io.

Introduction

Genome-wide epigenetic studies have gained much attention recently, and numerous studies reported associations between epigenetic modifications and biological conditions. Particularly, recently introduced high-throughput technologies for probing DNA methylation states have resulted in a mounting evidence for the suggested role of methylation in disease and complex cellular processes. Epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) have especially become a compelling and successful study design. In EWAS, methylation states are first read in many loci across the genome from a group of individuals, typically using the Illumina methylation arrays (27K, 450K and EPIC/850K). Then, probed methylation levels are tested for associations with a phenotype of interest. While simple in principle, revealing meaningful associations is often complicated due to various reasons, such as artificial disruptions in probe specificity (Chen et al., 2013) or the presence of confounders in the data, such as cell type composition (Jaffe and Irizarry, 2014) and population structure (Michels et al., 2013).

Naturally, methods and tools often need to be tailor-made for the analysis of methylation, in order to address the unique properties of the data. As a result, a growing repertoire of available comprehensive toolsets for methylation analysis has been suggested (e.g. Aryee et al., 2014; Assenov et al., 2014). Here, we present GLINT, a command-line toolset for performing EWAS, similar in spirit to PLINK (Purcell et al., 2007), a widely used command-line tool for performing genome-wide association studies (GWAS). While most of the existing tools for running EWAS require some programming proficiency, GLINT allows to run an EWAS pipeline easily and quickly using merely several simple commands which do not require any programming skills. GLINT provides automatic data management procedures and the implementation of several algorithms designed for methylation data. GLINT mainly provides implementation of recently suggested algorithms that are currently not available in existing toolsets, including improved reference-free estimation of cell type composition, inference of population structure from methylation and imputation of methylation levels from genotypes. Developed under a modular design, GLINT will allow an easy implementation of future algorithms and functionalities.

2 Materials and Methods

GLINT was developed in Python 2.7 and was designed to work on array methylation data (specifically, the Illumina 27K, 450K and EPIC/850K arrays). GLINT does not provide normalization and quality control procedures for raw IDAT files of methylation signals, but rather it focuses on analysis of preprocessed data. Given beta-normalized methylation levels (i.e. after raw data normalization), GLINT provides the following functionalities:

2.1 Data management

Quality control procedures for filtering out undesired methylation probes, including automatic exclusion of probes potentially introducing artificial variation (Chen et al., 2013), and procedures for filtering out undesired samples, including outliers detection and removal.

2.2 Adjusting for tissue heterogeneity

Estimation of cell type composition of samples coming from heterogeneous source (e.g., whole blood) using a supervised algorithm, which leverages reference methylation data of sorted cells (Houseman et al., 2012), and using ReFACTor (Rahmani et al., 2016), an unsupervised algorithm which does not require any reference. The estimated cell type composition can be then incorporated as covariates in a subsequent association testing or be used independently.

2.3 Inferring population structure

Inferring population structure directly from methylation data without the need for genotypes using the EPISTRUCTURE algorithm (Rahmani et al., 2017), which leverages the correlation structure of methylation with genetics in order to capture ancestry information. The latter can be then incorporated as covariates in a subsequent association testing or be used independently.

2.4 Methylation imputation

Imputation of methylation levels from genotypes, based on summary statistics fitted in linear models of methylation sites using genotype data as predictors (Rahmani et al., 2017), similarly to a recently suggested method for gene expression prediction from genotypes (Gamazon et al., 2015). Since some methylation sites can be well approximated by a weighted combination of several SNPs (Rahmani et al., 2017), performing association testing on such predicted methylation levels can be regarded as GWAS of pre-selected weighted sets of SNPs, which may potentially lead to novel findings. For demonstrating the utility of this approach, we used the WTCCC genotype data collected from rheumatoid arthritis cases and controls (Burton et al., 2007). Conducting EWAS on the imputed methylation levels revealed a new association that could not be discovered by a standard GWAS (Fig. 1), thus showing the potential of this approach in discovering novel associations.

Fig. 1.

Manhattan plots resulted from testing genome-wide markers for association with rheumatoid arthritis. Left: GWAS results of 344 943 markers reveal significant loci in chromosomes 1 and 6. Right: EWAS results of 1793 imputed markers that were found to be the most predictive by genetics reveal a novel association in chromosome 10 that was not detected in the GWAS (cg24591913; )

2.5 Association testing

Testing for phenotype-methylation associations using several different models and statistical tests: linear and logistic regression models, Wilcoxon rank-sum test and linear mixed models (LMMs), which were previously suggested for methylation data (Zou et al., 2014).

2.6 Visualization

Generation of publication-quality figures, including qq-plots and Manhattan plots for visualization of EWAS results.

3 Results

3.1 Usage

The online documentation of GLINT includes references and details about each of the methods implemented. Additionally, we provide an example data set with a quick start tutorial demonstrating how to work with GLINT.

3.2 Performance

We evaluated the performance of GLINT by running an EWAS pipeline on approximately 480 K sites: data loading, exclusion of problematic probes and performing association test (linear regression) while accounting for tissue heterogeneity (Fig. 2). On a 64-bit Mac OS X computer with 3.1GHz and 16GB of RAM the analysis required 9 min for 500 samples, 13 min for 1000 samples and 24 min for 2000 samples.

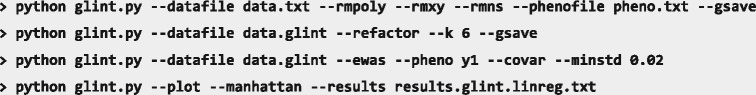

Fig. 2.

An example of a set of simple GLINT commands for performing an EWAS pipeline: excluding problematic probes (Chen et al., 2013), accounting for tissue heterogeneity (Rahmani et al., 2016), performing association test, and plotting the results.

4 Discussion

We note that some of the currently implemented functionalities were directly designed for data generated using the common 450 K array. As a result, while data generated using the new EPIC array can be analyzed with GLINT, some of the functionalities are expected to further benefit from specific adaptations according to the settings of the EPIC array. These will be made possible as more EPIC data become available.

Acknowledgements

This study makes use of data generated by the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. A full list of the investigators who contributed to the generation of the data is available from www.wtccc.org.uk. Funding for the project was provided by the Wellcome Trust under award 076113.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the Edmond J. Safra Center for Bioinformatics at Tel Aviv University. E.H., E.R., L.S. and R.S. were supported in part by the Israel Science Foundation (Grant 1425/13), E.H., L.S. and R.S. by the United States Israel Bintional Science Foundation grant 2012304. E.R. and L.S. were supported by Len Blavatnik and the Blavatnik Research Foundation. R.S. was supported by the Colton Family Foundation. N.Z. was supported in part by an NIH career development award from the NHLBI (K25HL121295).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Aryee M.J. et al. (2014) Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics, 30, 1363–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assenov Y. et al. (2014) Comprehensive analysis of DNA methylation data with RnBeads, Bioinformatics, 11, 1138–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton P. et al. (2007) Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature, 447, 661–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. et al. (2013) Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics, 8, 203–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamazon E.R. et al. (2015) A gene-based association method for mapping traits using reference transcriptome data. Nature Genetics, 47, 1091–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houseman E.A. et al. (2012) DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC Bioinformatics, 13, 1.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe A., Irizarry R.A. (2014) Accounting for cellular heterogeneity is critical in epigenome-wide association studies. Genome Biol., 15, 1.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels K.B. et al. (2013) Recommendations for the design and analysis of epigenome-wide association studies. Nature Methods, 10, 949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S. et al. (2007) PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 81, 559–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani E. et al. (2016) Sparse PCA corrects for cell type heterogeneity in epigenome-wide association studies. Nature Methods, 13, 443–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani E. et al. (2017) Genome-wide methylation data mirror ancestry information. Epigenetics & Chromatin, 10, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J. et al. (2014) Epigenome-wide association studies without the need for cell-type composition. Nature Methods, 11, 309–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]