Abstract

Background

While clinicians are expected to routinely assess and address suicide risk, existing data provide little guidance regarding the significance of visit-to-visit changes in suicidal ideation.

Methods

Electronic health records from four large healthcare systems identified patients completing the Patient Health Questionnaire or PHQ9 at outpatient visits. For patients completing two questionnaires within 90 days, health system records and state vital records were used to identify nonfatal and fatal suicide attempts. Analyses examined how changes in PHQ9 item 9 responses between visits predicted suicide attempt or suicide death over 90 days following the second visit.

Results

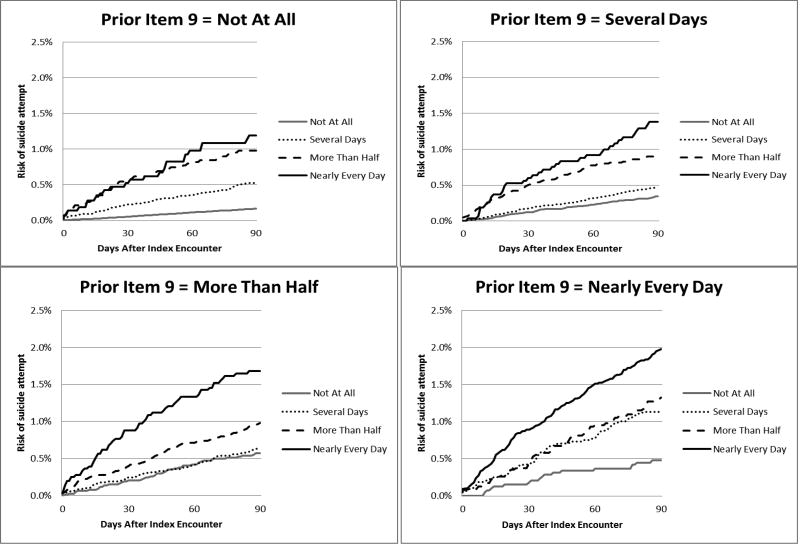

Analyses included 430,701 pairs of item 9 responses for 118,696 patients. Among patients reporting thoughts of death or self-harm “nearly every day” at the first visit, risk of suicide attempt after the second visit ranged from approximately 2.0% among those reporting continued thoughts “nearly every day” down to 0.5% among those reporting a decrease to “not at all”. Among those reporting thoughts of death or self-harm “not at all” at the first visit, risk of suicide attempt following the second visit ranged from approximately 0.2% among those continuing to report such thoughts “not at all” up to 1.2% among those reporting an increase to “nearly every day”.

Conclusions

Resolution of suicidal ideation between visits does imply a clinically important reduction in short-term risk, but prior suicidal ideation still implies significant residual risk. Onset of suicidal ideation between visits does not imply any special elevation compared to ongoing suicidal ideation. Risk is actually highest for patients repeatedly reporting thoughts of death or self-harm.

Keywords: suicide, risk, epidemiology, diagnosis, injuries, poisoning

Research regarding suicide risk in clinical populations has typically focused on identifying who is at risk of suicidal behavior or suicide death. This research has identified several stable patient characteristics associated with long-term risk of suicidal behavior, including psychiatric diagnoses, history of suicide attempt, and exposure to stressful life events (Mann, Apter et al. 2005, Nock, Borges et al. 2008, Hawton and van Heeringen 2009). Recent research in US military and veteran populations has found that similar stable patient characteristics predicts risk of suicide after a psychiatric hospitalization (Kessler, Warner et al. 2015) or a mental health outpatient visit (McCarthy, Bossarte et al. 2015, Kessler, Stein et al. 2016).

Clinicians face a more challenging task: identifying when an individual patient is at higher or lower risk. Decisions regarding intensive monitoring or hospitalization require clinicians to assess and respond to changes in risk between visits. Available evidence offers little help with those decisions (Glenn and Nock 2014, Bolton, Gunnell et al. 2015, Ribeiro, Franklin et al. 2015), and clinical guidelines are based primarily on expert opinion. American Psychiatric Association recommendations (Work Group on Suicidal Behaviors 2004) focus on initial assessment without addressing changes in risk over time. Other guidelines (Assessment and Management of Risk for Suicide Working Group 2013, Bolton, Gunnell et al. 2015) do recommend adjusting follow-up according to current risk, but do not address visit-to-visit changes in suicidal ideation.

We have previously reported that thoughts of death or self-harm measured by item 9 of the commonly-used Patient Health Questionnaire or PHQ9 (Kroenke, Spitzer et al. 2001, Kroenke, Spitzer et al. 2010) identify individuals at long-term risk for suicide attempt and suicide death (Simon, Rutter et al. 2013, Simon, Coleman et al. 2016). Practicing clinicians will increasingly be expected to use such standard measures to assess near-term risk. A recent Sentinel Event Alert from the US Joint Commission (Patient Safety Advisory Group 2016) recommends routine assessment of suicidal ideation using measures such as the PHQ9. Practice guidelines for the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs now recommended standardized assessment and recording of suicide risk (Assessment and Management of Risk for Suicide Working Group 2013). New “report card” measures for quality of depression care Proposals to include use of the PHQ9 in US health system quality reports (National Committee for Quality Assurance 2016) will emphasize systematic use of self-report measures such as the PHQ9.

In response to these developments, healthcare systems have increased use of the PHQ9 in both primary care and specialty mental health clinics. As clinicians and health system managers encounter large numbers of patients reporting frequent thoughts of death or self-harm, two practical questions have arisen: Does an apparent decrease in suicidal ideation (i.e. decreasing score on PHQ9 item 9) actually imply a decrease in risk of subsequent suicidal behavior? Does the apparent onset of suicidal ideation imply an increase in risk compared to pre-existing or “chronic” suicidal ideation? Here we use longitudinal data from over 100,000 patients receiving mental health care in four large health systems to examine those two practical questions.

METHODS

Data were drawn from four health systems (Kaiser Permanente Washington/Group Health Cooperative, HealthPartners, Kaiser Permanente of Colorado and Kaiser Permanente of Southern California) participating in the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN), a National Institute of Mental Health-funded consortium of research centers affiliated with integrated healthcare systems. Each of these systems provides general medical and specialty mental health care to a defined population, with a combined membership over 5 million. Patients are enrolled through a mixture of employer-sponsored insurance, individual insurance, capitated Medicare and Medicaid programs, and other government-subsidized low-income programs. Patient populations are generally representative of each system’s geographic area. All four systems recommended routine use of the PHQ9 depression questionnaire in depression care and all four routinely recorded ICD-9 E-code diagnoses, allowing accurate ascertainment of suicide attempts (Lu, Stewart et al. 2014). Across these systems, electronic health records and insurance claims have been organized in a Virtual Data Warehouse to facilitate population-based research (Ross, Ng et al. 2014). Institutional Review Boards at each health system approved use of de-identified health system data for this research.

The PHQ9 is a widely used self-report questionnaire assessing symptoms of depression during the prior two weeks (Kroenke, Spitzer et al. 2001, Kroenke, Spitzer et al. 2010). Item 9 asks how frequently the respondent has experienced “thoughts of death or of hurting yourself in some way”, with response categories including “not at all”, “several days”, “more than half the days”, and “nearly every day”. In general medical clinics, questionnaires were administered by nursing staff prior to the physician visit or by the physician during the visit. Some mental health clinics routinely administered the PHQ9 prior to every visit, and some relied on providers to administer it as clinically indicated.

The study sample included PHQ9 results in electronic health records between 1/1/2007 and 12/31/2013. We selected all PHQ9 records with a previous PHQ9 result less than or equal to 90 days prior (i.e. all pairs of adjacent PHQ9 results separated by no more than 90 days). The second observation in every pair was considered the index visit for assessment of subsequent risk. Any individual patient could contribute multiple pairs of PHQ9 observations to this sample (e.g. a patient with four PHQ9 results could contribute up to three distinct pairs if intervals between consecutive questionnaires were no more than 90 days). To exclude screening questionnaires, the sample was limited to questionnaires completed at mental health specialty visits and questionnaires completed at general medical visits associated with current or recent mental health diagnoses or prescriptions.

Nonfatal suicide attempts during the 90 days after each index visit were identified using electronic health records (for services provided at health system facilities) and insurance claims (for services provided by external providers or facilities). Qualifying diagnoses included:

ICD-9 diagnosis of self-inflicted injury or poisoning (E950 through E958)

ICD-9 diagnosis of injury or poisoning considered possibly self-inflicted (E980 through E988)

ICD-9 diagnosis of suicidal ideation (V62.84) accompanied by a diagnosis of either poisoning (960 through 989) or open wound (870 through 897).

We have previously reported (Simon, Savarino et al. 2006, Simon and Savarino 2007, Simon, Rutter et al. 2013) that validation by clinician review of 200 full-text medical records found a positive predictive value of 100% for the first criterion for suicide attempt, 80% for the second, and 86% for the third.

To evaluate the proportion of medically treated suicide attempts that might be missed by this method, we examined the proportion of emergency department and hospital encounters for injury or poisoning in which a cause-of-injury code (or E-code) was not recorded (Simon and Savarino). In 2010, the proportion of injury or poisoning encounters with no E-code ranged from 11 to 26% in these four health systems (Lu, Stewart et al. 2014).

Suicide deaths during the 90 days after each index visit were identified using state death certificate records, including ICD-10 cause-of-death codes for definite self-inflicted injury (X60 to X84) or possible self-inflicted injury (Y10 through Y34).

Each new index questionnaire defined a new period at risk, and each patient could contribute multiple overlapping risk periods by completing multiple PHQ9s. Each suicide attempt or death could be linked to multiple prior PHQ9 results from a single patient. This approach examines risk based on data available when the PHQ9 was completed, regardless of subsequent questionnaire completion. It avoids informative censoring that would occur if the likelihood of completing a later PHQ9 was related to risk of a subsequent suicide attempt. Each risk period was censored at the time of disenrollment from the health system, death from causes other than suicide, or the end of the study period (12/31/2013). PHQ9s administered after a recorded suicide attempt were not included in our analyses, because predictors of repeat suicide attempts would be expected to differ from predictors of first attempts.

Descriptive analyses examined the hazard of any suicide attempt (fatal or non-fatal) over 90 days following the index PHQ9 response. Cumulative hazard estimates were calculated for each combination of responses to PHQ9 item 9 at the index visit and at the most recent prior visit (i.e. four possible responses at index visit times four possible responses at the previous visit equals 16 possible combinations).

Partly conditional Cox proportional hazards regression (Zheng and Heagerty 2005) was used to estimate the association between response to item 9 and risk of any subsequent suicide attempt after stratifying the baseline hazard function on site and accounting for potential confounders (age, sex, and race/ethnicity). The hazard associated with responding “nearly every day”, “more than half the days”, and “several days” was compared to the hazard associated with responding “not at all” (the reference group). Models also considered all possible combinations of responses at the index and previous visits. Step-wise model fitting examined the contribution of item 9 response at the index visit, then the added contribution of item 9 response at the previous visit, and then the interaction between those two item 9 response (i.e. total of 15 indicators to account for 16 possible combinations). Confidence intervals were constructed using the robust sandwich estimator to calculate the standard errors to account for multiple pairs of PHQ9 responses per person (Lin and Wei 1989). We report hazard ratio (HR) estimates and 95% confidence intervals for estimates as well as Wald p-values (Wald 1945, Rotnitzky and Jewell 1990) evaluating if any of a group of covariates adds predictive value of the model for suicide attempt or death. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

The criteria described above identified 430,701 pairs of item 9 responses for 118,696 patients, including 55,819 patients (47%) contributing a single pair, 21,121 (18%) contributing two pairs, 23,124 (19%) contributing three to five pairs, 9393 (8%) contributing six to nine, and 9239 (8%) with ten or more. Of these patients, 80,694 (68%) were female. The racial and ethnic distribution was 80,192 (68%) non-Hispanic White; 6967 (6%) non-Hispanic black; 14,758 (12%) Hispanic; 3745 (3%) Asian; 612 (<1%) Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; 260 (<1%) Native American/Alaskan Native; 3119 (3%) reporting multiple or mixed race; and 9043 (8%) from other groups or missing information regarding race and ethnicity. Index encounters included 305,951 (71%) with specialty mental health providers, 62,801 (15%) with primary care providers, and 61,949 (15%) with emergency departments or other medical specialties. Within each pair, the interval between visits with PHQ9 responses was 14 days or less for 146,752 (34%), 15 to 30 days for 122,011 (28%), 31 to 44 days for 72,238 (17%), and 45 to 90 days for 89,700 (21%).

As shown in Table 1, approximately 3% of patients reported thoughts of death of self-harm “nearly every day” and approximately 5% reported such thoughts “more than half the days” at the index visit. Agreement in item 9 responses between visits was moderate, with a weighted kappa statistic (Cohen 1960) of 0.46 (T=413, p<0.001). Approximately 9700 patients showed an apparent resolution of frequent suicidal ideation, shifting to “not at all” from “more than half the days” or “nearly every day”. Approximately 5400 showed an apparent onset of frequent suicidal ideation, shifting to “more than half the days” or “nearly every day” from “not at all”.

Table 1.

Cross-classification of PHQ9 item 9 responses at the index encounter and most recent prior encounter. Table cells report number of PHQ9 observations and row percentages.

| PHQ9 Item 9 Response at Index Encounter | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ9 Item 9 Response at Previous Encounter |

Not at all | Several days | More than half the days |

Nearly every day |

Total |

| Not at all | 292,139 (92%) | 19,337 (6%) | 3582 (1%) | 1871 (<1%) | 316,929 (100%) |

| Several days | 31,925 (45%) | 29,920 (42%) | 6563 (9%) | 2248 (3%) | 70,656 (100%) |

| More than half the days | 6398 (25%) | 8438 (33%) | 7774 (31%) | 2909 (11%) | 25,519 (100%) |

| Nearly every day | 3351 (19%) | 3334 (19%) | 3670 (21%) | 7242 (41%) | 17,597 (100%) |

| Total | 333,813 (78%) | 61,029 (14%) | 21,589 (5%) | 14,270 (3%) | 430,701 (100%) |

Medical records, insurance claims, and death certificate data identified a total of 742 fatal and non-fatal suicide attempts in the 90 days following the index visit. This included 49 (7%) suicide deaths, 497 (67%) non-fatal attempts with diagnoses of definite self-inflicted injury, 149 (20%) non-fatal attempts with diagnoses of possible self-inflicted injury, and an additional 47 (6%) attempts identified by the combination of a poisoning or wound diagnosis linked to a diagnosis of suicidal ideation. Of suicide deaths, 18 were by overdose or self-poisoning and 31 were by self-inflicted injury (gunshot wound, jumping, hanging, laceration, etc.). Of non-fatal suicide attempts, 584 (84%) were by overdose or self-poisoning and 109 (16%) were by self-inflicted injury. Of non-fatal suicide attempts, 399 (58%) resulted in hospitalization.

Figure 1 shows the cumulative hazard of fatal or nonfatal suicide attempt over 90 days according to item 9 response at the index visit, with panels stratified by item 9 response at the prior visit. Comparison of lines within each panel shows that item 9 response at the index visit was a strong predictor of subsequent suicide attempt, regardless of response at the prior visit. Comparison across panels shows that item 9 response at the prior visit was a modest predictor of subsequent suicide attempt, regardless of response at the index visit.

Figure 1.

Cumulative risk of any suicide attempt according to response to PHQ9 item 9. Four panels are stratified by item 9 response at most recent prior encounter, and lines within each panel show risk according to item 9 response at index visit.

The relative contributions of index visit response and prior visit response were examined in a partly conditional Cox proportional hazards model predicting risk of fatal or nonfatal suicide attempt. In a model stratified on site, containing age, sex, race/ethnicity, and response to item 9 at the index visit, the addition of item 9 response at the prior visit made a significant additional contribution to prediction (Wald chi-square=72.9, df=3, p<.0001). Interaction of index and prior responses made significant additional contribution (Wald chi-square=53.7, df=9, p<.0001). In Appendix Table 1, we report the coefficient estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the hazard ratios estimates in each of those three models.

Table 2 displays the estimated relative hazards of suicide attempt from the final model including index visit response, prior response, and the interaction of the two. Consistent with Figure 1, relative hazard of suicide attempt increased dramatically according to index visit response (from left to right) and moderately with prior response (from top to bottom).

Table 2.

Estimated relative hazards of suicide attempt or suicide death (with 95% confidence interval) according to index visit response and most recent prior responses to PHQ9 item 9. Upper right, shaded section indicates an increase in frequency of reported suicidal ideation from previous visit. Lower left indicates a decrease in frequency of reported suicidal ideation from previous visit, while diagonal represents no change in frequency of reported suicidal ideation.

| INDEX VISIT RESPONSE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRIOR VISIT RESPONSE | Not at all | Several days | More than half the days |

Nearly every day |

| Not at all | 1 (reference) | 3.29 (2.65, 4.08) | 6.13 (4.38, 8.57) | 7.37 (4.89, 11.11) |

| Several days | 2.09 (1.72, 2.54) | 2.85 (2.19, 3.72) | 5.62 (4.22, 7.49) | 8.48 (5.78, 12.43) |

| More than half the days | 3.48 (2.53, 4.80) | 3.86 (2.89, 5.15) | 6.03 (4.39, 8.29) | 10.52 (7.59, 14.59) |

| Nearly every day | 2.93 (1.82, 4.70) | 7.00 (4.97, 9.87) | 8.11 (5.91, 11.13) | 12.28 (8.90, 16.94) |

The implications of an apparent resolution of suicidal ideation are illustrated in the bottom row of Table 2. Among those reporting suicidal ideation “nearly every day” at the prior visit, risk of suicide attempt was markedly lower among those reporting a decrease to “not at all” at the index visit compared to those continuing to report such thoughts “nearly every day”. Direct comparison of those two groups yielded a hazard ratio of 0.24 (95% CI: 0.14–0.41). But the group reporting apparent resolution of suicidal ideation (bottom left cell) still experienced approximately three-fold greater risk than responding “not at all” on both occasions (reference cell in upper left).

The implications of an apparent onset of suicidal ideation between visits are illustrated by the upper right portion of Table 2. Among those reporting suicidal ideation “not at all” at the prior visit, an increase to “nearly every day” at the index visit was associated with a more than seven-fold increase in risk compared to those reporting suicidal thoughts “not at all” on both occasions. But risk of suicide attempt was higher still in those reporting frequent suicidal thoughts on both occasions (bottom right corner). Direct comparison of those repeatedly reporting frequent suicidal thoughts (lower right) and those reporting apparent onset of frequent suicidal thoughts (upper right) yielded a hazard ratio of 1.66 (95% CI: 1.03–2.68).

DISCUSSION

In this large and diverse sample of outpatients treated in four health systems, increases or decreases in response to PHQ9 item 9 were associated with clinically important changes in subsequent risk of suicide attempt. Patients reporting frequent thoughts of death or self-harm on two consecutive visits had a 2% risk of suicide attempt over the following 90 days. For perspective, that approximates the 1-year risk of major cardiovascular event in a 50 year-old male smoker with diabetes and moderately elevated blood pressure (Lloyd-Jones 2010). While this absolute risk level might not warrant hospitalization or emergency intervention, it does identify patients in need of regular follow-up and long-term interventions to reduce risk.

Regarding apparent decreases in frequency of suicidal ideation: Our data support the common clinical recommendation that a decrease in frequency of suicidal thoughts implies a true decrease in short-term risk of suicidal behavior and decreased need for more intensive treatment or monitoring. We should emphasize, however, that the apparent “resolution” of suicidal ideation (as assessed by item 9 of the PHQ9) does not imply that short-term risk declines to the level of those never reporting suicidal thoughts. A past report of frequent suicidal ideation does imply some enduring vulnerability. In quantitative terms, a change from reporting suicidal ideation “nearly every day” to “not at all” implies a 75% reduction in short-term risk, but risk remains three times as high compared to those without recent suicidal ideation.

We do not find that apparent onset of suicidal ideation implies some special increase in risk. In fact, we observe that those reporting thoughts of death or self-harm “nearly every day” at two consecutive encounters were 65% more likely to attempt suicide over the following 90 days than were those who appeared to report the onset of frequent suicidal ideation between visits. We find no evidence that repeated endorsement of suicidal ideation or “chronic suicidality” implies a lower level of risk or a lower need for risk assessment or follow-up.

Our analyses focus on visit-to-visit changes in response to PHQ9 item 9, and we do not examine more stable patient characteristics, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, diagnosis and clinical history. As indicated by previous research (Kessler, Warner et al. 2015, McCarthy, Bossarte et al. 2015, Kessler, Stein et al. 2016), considering those characteristics would certainly improve risk prediction and facilitate identifying patients at highest risk. Those stable characteristics cannot, however, inform decisions regarding short-term changes in risk.

Included patients represent a wide range of age, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Consequently, we believe these results should be broadly generalizable to patients receiving outpatient mental health care in the U.S. We have no data, however, regarding people who do not seek care, who decline to complete questionnaires, or who drop out of care after a completing a single questionnaire. Limiting our sample to patients making repeated visits would be expected to select those at higher risk of suicide attempt, and this is confirmed by comparison of this sample with our previous reports (Simon, Rutter et al. 2013, Simon, Coleman et al. 2016) including all patients completing PHQ9 questionnaires.

Our data regarding suicidal ideation are limited to thoughts of death or self-harm self-reported on a brief depression questionnaire. We cannot determine how these results might apply to more detailed assessments specifically focused on suicide risk, suicidal intent, or suicide plans (Beck, Brown et al. 1999, Posner, Brown et al. 2011, Bolton, Gunnell et al. 2015).

Treating clinicians were aware of PHQ9 responses and were expected to provide additional assessment and follow-up care, including possible hospitalization. The suicide attempts and suicide deaths in this sample occurred despite any such treatment intensification.

Our ascertainment of suicide attempts may have included some instances of minor self-inflicted injury without suicidal intent, but this proportion would be small. Only 16% of non-fatal suicide attempts were by self-inflicted injury, and 58% of all non-fatal attempts resulted in hospitalization.

We cannot determine whether these findings apply specifically to suicide deaths. We have previously reported that response to PHQ9 item 9 is a robust predictor of suicide death over 12 to 18 months (Simon, Rutter et al. 2013, Simon, Coleman et al. 2016). But the number of suicide deaths over 90 days in this sample (49) was too small to support any interaction or subgroup analyses regarding changes in suicidal ideation between visits. The numbers of suicide deaths according to item 9 responses at the index visit and prior visit are reported in Appendix Table 2.

From a population perspective, our findings offer guidance regarding the implications of suicidal ideation for the long- and short-term risk of suicidal behavior. As we have previously reported, outpatients who report frequent thoughts of death or self-harm at a visit remain at significantly higher risk of suicide attempt and suicide death for up to two years after the heath care visit (Simon, Rutter et al. 2013, Simon, Coleman et al. 2016). An elevated score for item 9 of the PHQ9 depression questionnaire identifies patients in need of long-term monitoring and sustained interventions to reduce risk. As we report here, short-term decreases in response to item 9 do indicate a reduction in near-term risk, but not an elimination of that risk.

For practicing clinicians, our findings suggest that current suicidal ideation is a powerful indicator of near-term risk, independent of past reports of suicidal ideation. Individuals who reported thoughts of death or self-harm at a prior visit remain at moderately increased risk even if they report no such thoughts at the current visit. While the apparent onset of suicidal thoughts does predict significant risk, risk is actually highest for patients reporting sustained or repeated thoughts of death or self-harm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by Cooperative Agreement U19MH092201 with the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Institutions at which work was performed: Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, WA; Kaiser Permanente Colorado Institute for Health Research, Denver, CO; Kaiser Permanente Southern California Department of Research and Evaluation, Pasadena, CA; HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, MN

The authors have no relevant financial interests to disclose.

References

- Assessment and Management of Risk for Suicide Working Group. The VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Assessment and Management of Patients at Risk for Suicide. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA, Dahlsgaard KK, Grisham JR. Suicide ideation at its worst point: a predictor of eventual suicide in psychiatric outpatients. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1999;29(1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton JM, Gunnell D, Turecki G. Suicide risk assessment and intervention in people with mental illness. Bmj. 2015;351:h4978. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement of nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;30:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Nock MK. Improving the short-term prediction of suicidal behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3 Suppl 2):S176–180. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. Lancet. 2009;373(9672):1372–1381. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60372-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Stein MB, Petukhova MV, Bliese P, Bossarte RM, Bromet EJ, Fullerton CS, Gilman SE, Ivany C, Lewandowski-Romps L, Millikan Bell A, Naifeh JA, Nock MK, Reis BY, Rosellini AJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Ursano RJ, Army SC. Predicting suicides after outpatient mental health visits in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Mol Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.110. ((epub July 19)) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Warner CH, Ivany C, Petukhova MV, Rose S, Bromet EJ, Brown M, 3rd, Cai T, Colpe LJ, Cox KL, Fullerton CS, Gilman SE, Gruber MJ, Heeringa SG, Lewandowski-Romps L, Li J, Millikan-Bell AM, Naifeh JA, Nock MK, Rosellini AJ, Sampson NA, Schoenbaum M, Stein MB, Wessely S, Zaslavsky AM, Ursano RJ, Army SC. Predicting suicides after psychiatric hospitalization in US Army soldiers: the Army Study To Assess Risk and rEsilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(1):49–57. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY, Wei LJ. The robust inference for the proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84:1074–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones DM. Cardiovascular risk prediction: basic concepts, current status, and future directions. Circulation. 2010;121(15):1768–1777. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.849166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CY, Stewart C, Ahmed AT, Ahmedani BK, Coleman K, Copeland LA, Hunkeler EM, Lakoma MD, Madden JM, Penfold RB, Rusinak D, Zhang F, Soumerai SB. How complete are E-codes in commercal plan claims databases? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:218–220. doi: 10.1002/pds.3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hegerl U, Lonnqvist J, Malone K, Marusic A, Mehlum L, Patton G, Phillips M, Rutz W, Rihmer Z, Schmidtke A, Shaffer D, Silverman M, Takahashi Y, Varnik A, Wasserman D, Yip P, Hendin H. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294(16):2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JF, Bossarte RM, Katz IR, Thompson C, Kemp J, Hannemann CM, Nielson C, Schoenbaum M. Predictive Modeling and Concentration of the Risk of Suicide: Implications for Preventive Interventions in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1935–1942. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS Depression Measures Specified for Electronic Clinical Data Systems. 2016 Retrieved February 16, 2016, from http://www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement/HEDISLearningCollaborative/HEDISDepressionMeasures.aspx.

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:133–154. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient Safety Advisory Group. Detecting and treating suicidal ideation in all settings. The Joint Commission Sentinel Event Alerts. 2016;56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, Mann JJ. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Chang BP, Nock MK. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 2015:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross TR, Ng D, Brown JS, Pardee R, Hornbrook MC, Hart G, Steiner JF. The HMO Research Network Virtual Data Warehouse: A Public Data Model to Support Collaboration. eGEMs. 2014;2(1) doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotnitzky A, Jewell N. Hypothesis testing of regression parameters in semiparametric generalized linear models for cluster correlated data. Biometrika. 1990;77:485–497. [Google Scholar]

- Simon G, Savarino J. Suicide attempts among patients starting depression treatment with medication or psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G, Savarino J, Operskalski B, Wang P. Suicide risk during antidepressant treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:41–47. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Coleman KJ, Rossom RC, Beck A, Oliver M, Johnson E, Whiteside U, Operskalski B, Penfold RB, Shortreed SM, Rutter C. Risk of suicide attempt and suicide death following completion of the Patient Health Questionnaire depression module in community practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(2):221–227. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m09776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, Oliver M, Whiteside U, Operskalski B, Ludman EJ. Does Response on the PHQ-9 Depression Questionnaire Predict Subsequent Suicide Attempt or Suicide Death? Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(12):1195–1202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Savarino J. Suicide attempts among patients starting depression treatment with medications or psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7):1029–1034. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald A. Sequential tests of statistical hypotheses. Ann Math Statist. 1945;16:117–186. [Google Scholar]

- Work Group on Suicidal Behaviors. Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Patients with Suicidal Behaviors. Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Heagerty PJ. Partly conditional survival models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 2005;61(2):379–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.