Abstract

Introduction

Despite availability of effective care strategies for dementia, most health care systems are not yet organized or equipped to provide comprehensive family-centered dementia care management. Maximizing Independence at Home-Plus is a promising new model of dementia care coordination being tested in the U.S. through a Health Care Innovation Award funded by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services that may serve as a model to address these delivery gaps, improve outcomes, and lower costs. This report provides an overview of the Health Care Innovation Award aims, study design, and methodology.

Methods

This is a prospective, quasi-experimental intervention study of 342 community-living Medicare–Medicaid dual eligibles and Medicare-only beneficiaries with dementia in Maryland. Primary analyses will assess the impact of Maximizing Independence at Home-Plus on risk of nursing home long-term care placement, hospitalization, and health care expenditures (Medicare, Medicaid) at 12, 18 (primary end point), and 24 months, compared to a propensity-matched comparison group.

Discussion

The goals of the Maximizing Independence at Home-Plus model are to improve care coordination, ability to remain at home, and life quality for participants and caregivers, while reducing total costs of care for this vulnerable population. This Health Care Innovation Award project will provide timely information on the impact of Maximizing Independence at Home-Plus care coordination model on a variety of outcomes including effects on Medicaid and Medicare expenditures and service utilization. Participant characteristic data, cost savings, and program delivery costs will be analyzed to develop a risk-adjusted payment model to encourage sustainability and facilitate spread.

Keywords: Care coordination, Dementia, Medicare, Medicaid, payment, caregivers

Introduction

Dementia is a high cost, high burden public health challenge that has been quickly rising as an international public health priority. An estimated 46.8 million persons are currently living with dementia worldwide, and in the absence of curative or disease altering therapies, this number will surpass 131 million by 2050. In the U.S., over five million Americans age 65 and older are estimated to have dementia, and similar to international forecasting trends, this number is expected to nearly triple by 2050.1,2 The economic impact of dementia is enormous and growing. Worldwide care costs for dementia totaled $818 billion in 2015 (US dollars) and will likely top 1 trillion (US dollars) by 2018.3 As one of the most expensive chronic conditions in the U.S.,4 an estimated $183 billion was spent on dementia-related health care; projections suggest annual spending will rise to $1.1 trillion by 2050.1 Beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) cost Medicaid an estimated 19 times ($10,120 per beneficiary per year (PBPY) versus $527 PBPY) and Medicare three times more ($43,847 PBPY versus $13,879 PBPY) than beneficiaries without AD, with early nursing home placements and potentially preventable hospitalizations being major cost drivers. The majority of persons with dementia (>70%) are being cared for at home, by more than 15 million informal family caregivers. These family caregivers contributed an estimated 18.2 billion hours of unpaid care in the U.S. in 2016 valued at $230.1 billion.1 Out-of-pocket care costs for persons with dementia and families are also significant—estimated at $34 billion in 2012.5 Beyond economic impacts, dementia places persons at high risk for nursing home placement, poor quality of life (QOL), serious behavioral problems, functional disability, depression, and general medical complications (e.g. urinary tract infections, falls).6–12 Family caregivers, often referred to as “the hidden patients,” are also at risk for physical and emotional distress, depression, social isolation, loss of work wages/employment, financial burden,13 and have an estimated sixfold higher risk of developing dementia themselves.14

Effective symptoms and disease management options are available15–22 and practice recommendations support the integration and coordinated use of evidence-based approaches to maximize effectiveness on outcomes.23–28 Optimal dementia care focuses on identifying and meeting multidimensional needs such as—but not limited to—management of cognitive and behavioral symptoms, multimorbidity and medical progression accelerator management (e.g. polypharmacy), attending to the living environment, providing social and supportive care in daily living (e.g. meaningful activities), as well as addressing caregiver needs (e.g. dementia care-related skills training and education, coping strategies and communication skills training, information about community supports, respite care, problem solving).25,28

In mainstream practice, however, care to persons with dementia and their families is often inadequate and usually not delivered as a comprehensive and coordinated set of services. A major barrier in the U.S. is that home and community-based services (HCBS), which are critical to dementia care, are inadequately financed.29,30 The federal-state Medicaid program serves those who are poor and have limited financial assets. States vary in the generosity and type of services that are covered through Medicaid although most provide some HCBS. While Medicaid has covered more HCBS in recent years, the program is still primarily geared toward covering institutional long-stay nursing facility services for those who are poor or become impoverished through out-of-pocket expenses for health and social care. The Medicare program that covers elderly and disabled beneficiaries regardless of income covers only very limited home health services and does not cover personal care assistance or care coordination services to support caregivers in helping persons with dementia reside at home. Overall, despite evidence supporting effective care strategies and approaches, the health care system is not yet organized, equipped, or incentivized to provide comprehensive family-centered dementia care management. As a result, modifiable and meaningful dementia-related care needs often go unevaluated and unmet,31–35 contributing to poor outcomes and higher costs. Thus, new models of care that address these delivery gaps, improve care outcomes, and reduce costs are critically needed for this vulnerable and growing population.

Care coordination models (e.g. care management, case management, collaborative care) specifically tailored to dementia represent a potentially potent tool to “connect the dots” in dementia care and promote better coordination, quality of care, and value. Available evidence suggests dementia-oriented care management is beneficial for both persons with dementia (e.g. improved guideline adherence, QOL, and reduced neuropsychiatric behavior, risk of institutionalization) and caregivers (e.g. reduced caregiver burden/strain/depression),36–40 although it is still difficult to draw precise conclusions due to variability in the quality of evidence. Further, there is a lack of data on cost of intervention delivery and cost savings to estimate potential for return on investment for implementation by systems and insurers. Promising models41–45 share similarities including a focus on the patient/caregiver dyad (as opposed to the patient alone); structured needs assessments; personalized care planning; ongoing monitoring and revisions of care plans; referrals and linkages to health care providers and community-based organizations; and care-giver support, problem solving, and skills training. Yet, each is unique in terms of intervention content and areas of focus, duration of intervention program (i.e. dose), integration with health systems and community-based organizations, staffing type and team composition, caseloads, delivery format (e.g. phone based, home based), intensity of contact, and targeted primary outcomes.

One such promising community-based model is the Maximizing Independence at Home model (MIND at Home).44 MIND at Home is characterized by its strong focus on the home as the nexus of dementia care coordination, its extensive needs assessment targeting both persons with dementia and their family caregivers that is linked to a set of need-based intervention protocols and care strategies derived from best practices and evidence-based research, its use of trained nonlicensed community workers as the frontline care coordinators (supported by geriatric psychiatrists, nurses), and its focus on person-centered outcomes (e.g. remaining at home for as long as possible, QOL). MIND at Home aligns with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, National Alzheimer’s Project Act, a law that requires the development of a National Plan for AD and other related diseases, and enables and encourages innovation and collaboration across federal programs to improve the trajectory of AD, as well as State HCBS waivers, and the mission for Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to promote individualized, patient-centric care for the dementia population. MIND at Home has been previously developed and tested in a series of studies35,44,46,47 including a pilot randomized controlled trial involving a cognitively and socioeconomically diverse sample of 303 community-living individuals with memory disorders. In this trial, MIND at Home led to significant delays in time to transition from home, fewer dementia-related unmet needs, improved QOL, and reduced caregiver objective burden (e.g. time savings) from baseline to 18 months compared to augmented usual care.44,47 However, the trial was not designed specifically to assess implementation costs and impacts on health care costs, both of which are critical to dissemination adoption and uptake by health care systems and insurers.

Funded by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) Health Care Innovation Award (HCIA) Round Two (09/01/2014–11/30/2017; 1C1CMS331332), and in partnership with two community-based organizations (i.e. Johns Hopkins Home Health Care Group and Jewish Community Services), we are currently testing implementation of an expanded, more intensive version of the MIND at Home care coordination model, called MIND at Home-Plus. The primary objective of the HCIA is to evaluate the impact of MIND at Home-Plus on improving the ability of community-living older adults with dementia to remain at home while improving care quality, enhancing QOL, and reducing total health care costs. Specifically the major analytical aims of this evaluation are to:

To determine the effectiveness of MIND at Home-Plus on risk of and time to nursing home long-term care (LTC) placement or death at 12, 18 (primary end point), and 24 months, compared to propensity-matched controls;

To estimate total cost savings to the Medicare and Medicaid programs at 12, 18 (primary end point), and 24 months, compared to propensity-matched controls;

To estimate within-group changes on dementia-related unmet care needs (total, domains), QOL, neuropsychiatric behaviors, as well as caregiver dementia-related unmet care needs (total, domains), subjective burden, objective burden, depression from baseline to nine months and 18 months (primary end point) for participants receiving MIND at Home-Plus; and

To determine the effectiveness of MIND at Home-Plus on risk and rate of hospitalizations, Emergency Department, and 30-day readmissions at 12 and 18 months (primary end point), compared to propensity-matched controls.

To achieve sustainability and facilitate spread, secondary HCIA objectives are to develop a sustainable payment model for MIND at Home-Plus by carrying out an evaluation of program costs and to develop a web-based certification package to promote dissemination and scalability. This article reports on the overall study design and methods of the HCIA project and a description of the MIND at Home-Plus model.

Methods

Study design

This is a prospective, quasi-experimental intervention trial design which will assess the impact of the MIND at Home-Plus dementia care coordination model in a cohort of 342 community-living individuals with dementia enrolled either in both Medicare and Medicaid (dual eligible) or Medicare-only living in the greater Baltimore and Maryland suburban District of Columbia (DC) region compared to a propensity-matched control group (clinicaltrials.gov; NCT02395731). MIND at Home-Plus services are delivered to participants for up to 24 months, with the primary endpoint for evaluation of impact on outcomes assessed at 18 months. This study was reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board and the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Institutional Review Board. Oral consent was obtained from participants (i.e. persons with cognitive disorder and/or family caregivers) during a telephone screen. Written consent was obtained from the participants and their study partners (i.e. a reliable family member or friend who knew the participant well) at the initial in-home assessment. For participants too impaired to provide consent, proxy consent was obtained from a legally authorized representative using the Maryland Health Care Decisions Act as a guide, with assent obtained from the participant.

Participants

A total of 342 community-residing persons with dementia were enrolled in the study between March 2015 and October 2016 through referrals from community organizations, health care providers, local and state Medicaid waiver programs, and health departments, and a broad community outreach campaign with community-based events and local media publicity. Eligible participants met all-cause dementia diagnostic criteria, were dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare benefits (inclusive of both partial and full duals) or Medicare-only, and were living at home in the community in the Greater Baltimore and DC suburban region (a 40 mile radius from Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center). Participants were not required to have a family caregiver (i.e. a person who provides nonpaid assistance in one or more instrumental activities of daily living (ADL)) but were required to have a knowledgeable study partner to provide proxy information. Select demographic and clinical characteristics for participants are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of persons with dementia enrolled in MIND at Home-Plus (n = 342).

| Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 80.7 (9.8) |

| Education (years of formal education/schooling) | 11.6 (5.6) |

| Medications, routine (number) | 8.5 (4.4) |

| MMSE Total Score (0 mild–30 severe dementia) | 17.1 (7.7) |

| NPI (frequency × severity) total (0 mild–144 severe behavioral disturbances) | 21.5 (1.0) |

| PGDRS (ADL dependency) total (0 not–39 severely impaired) | 11.6 (8.9) |

| Percent unmet JHDCNA 2.0© needs per person (0–100%) | 27.5 (11.4) |

| Percentage | |

| Female | 75 |

| Black/African American, Asian, or other nonwhite race | 70 |

| Living with caregiver | 66 |

| Dually eligible Medicare–Medicaid beneficiaries | 66 |

| ≥ 1 Hospitalization(s) past year | 40 |

Intervention

Overview of the MIND at Home-Plus model

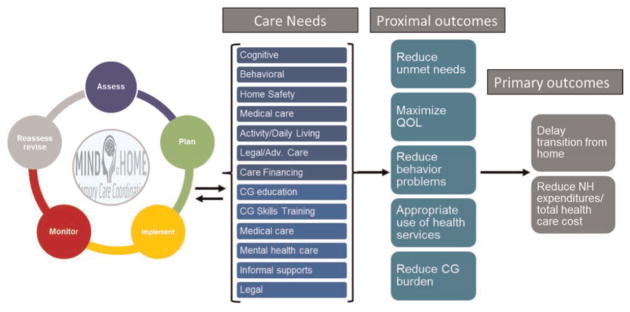

Informed by decades of dementia care clinical expertise,28 published recommended practice,23–28 observational and clinical studies,15–22,31–35,51 MIND at Home-Plus is a comprehensive, home-based dementia care coordination model that systematically assesses and addresses a broad range of unmet dementia-related care needs that place elders at risk for health disparities, unwanted LTC placement, poor QOL, and caregiver burden. The hypothesized mechanisms of action are in the Driver Diagram (Figure 1). MIND at Home-Plus uses a traditional care management process (i.e. comprehensive assessment, individualized care planning, implementation of the care plan, monitoring the impact over time, and reassessment and revising the care plan over time) to identify and address 13 broad care need domains (59 individual needs) for persons with dementia and care-giver. In turn, these care needs are hypothesized to impact proximal outcomes, which ultimately lead to risk of institutionalization and health care cost (Figure 1). MIND at Home-Plus expands on the prior MIND at Home model by the addition of an occupational therapist (OT)-led component, based on Tailored Activities Program (TAP) provided to a subset of who have extensive unmet needs related to behavior management and home safety issues.

Figure 1.

MIND at home model driver diagram. CG: caregiver; QOL: quality of life.

Care coordination team and delivery process

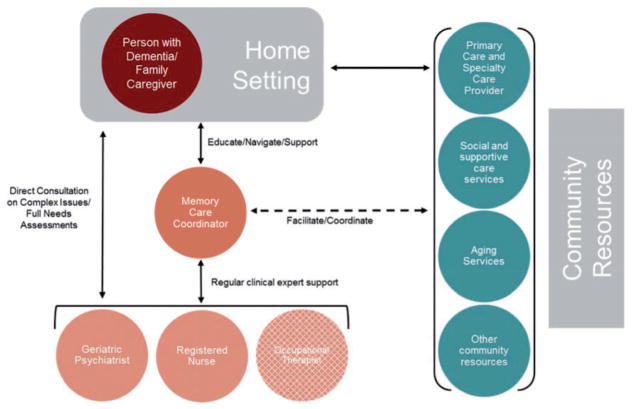

MIND at Home-Plus (Figure 2) is implemented by an interdisciplinary team that draws on and synthesizes the expertise and experience of nonclinical community workers (i.e. Memory Care Coordinators), nurses, physicians, and OTs. Memory Care Coordinators serve as the frontline interventionists and are trained and continuously supported and mentored by the clinical team. One FTE memory care coordinator can serve an optimal caseload of 40–50 dyads (i.e. persons with dementia and family caregiver). The memory care coordinator and nurse perform the initial in-home needs assessment and then work collaboratively on development of an initial care plan. The memory care coordinators carry out a follow-up home visit with the person with dementia and/or caregiver to review needs assessment results, prioritize needs with the family’s input, provide indicated educational materials, and decide on an agreed-upon individualized care plan. The care plan is then sent to both the caregiver and the person with dementia’s primary care physician and the plan is implemented. The type and frequency of coordinator involvement with the persons with dementia and family is individualized and driven by need level, care plan, and family preference. Memory Care Coordinators aim to have a contact every 30 days, at minimum. When indicated, coordinators and; MIND care team staff take a direct role in ensuring follow-through with recommended care options/strategies (e.g. reminders of appointments, attending outpatient visits or nursing home rehabilitation meetings, pricing medical equipment or services, assisting with service program applications, providing educational material, and modeling behavioral management techniques).

Figure 2.

MIND at Home-Plus Model.

The delivery process and core components of the MIND at Home model are listed below:

A 1.5 h initial in-home visit informs the Johns Hopkins Dementia Care Needs Assessment 2.0 (JHDCNA 2.0©) (Persons with Dementia and Informal Caregiver by Care Coordinator and Nurse). The JHDCNA assesses persons with dementia and caregiver needs and serves as the basis of the individualized care plan.

-

Individualized need-based care planning and standardized MIND service delivery

Written care plan (provided to family and primary care provider), prioritizing needs

-

Implement core care strategies per standardized protocol

Disorder education

Referrals and linking to community-based resources

Specific skills training/care strategies/problem solving

Emotional support

Symptom screening/needs assessment

Caregiver resource binder

Referral to OT for specialized protocols (TAP, Care of Persons with Dementia in their Environments)

-

Monitoring and revision of care plan

Memory care coordinator direct encounter every 30 days

Quality reviews every 60 days by clinical supervisor

Weekly care team rounds (addressing challenging/complex cases)

Tracking encounters in Dementia Care Management System (DCMS)

Full JHDCNA In-Home Reassessment (every nine months)

-

Critical events (e.g. hospitalizations, emergency room visits, falls) protocols are conducted in certain situations as described below:

As-needed clinician mobile telehealth visits within one week of discharge

As-needed clinician mobile telehealth visits to support coordinator in addressing pressing caregiver concerns, e.g. management of behavioral symptoms

Transitions/discharges

A subset of participants (about 20%) with extensive unmet needs related to behavior management and home safety issues may trigger up to 10 additional home sessions by the OT following COPE and TAP evidence-based protocols.52,53 These protocols involve up to 10 OT and nurse sessions to address ADL limitations; home safety evaluations; instructing caregivers in how to detect pain and manage issues related to hydration, constipation, medications; and developing meaningful activity prescriptions to boost program effectiveness in decreasing risk for LTC placement.

The MIND at Home care team is supported by a secure cloud-based electronic medical record custom built for the model, the DCMS. DCMS is customized care management software created specifically for the MIND program and allows Memory Care Coordinators to track progress of coordination, log contacts and care strategies employed, provide reminders for action items, manage and update referral directories for local health providers and community agencies. DCMS securely shares information in real time across the MIND at Home care team for higher quality care and self-monitoring.

Mobile telehealth is used on an as-needed basis in special circumstances that may require clinical input or supervision (such as checking in with a patient a week after discharge from the hospital). As MIND at Home does not deliver medical care—private and secure mobile telehealth is used to (1) more fully assess the situation by the MIND clinical team so that the appropriate clinical referrals can be made to the patient’s health care provider(s); (2) provide targeted behavioral management or health education to the caregiver, dementia care education, to help with problem solving, or otherwise supplement the coordination activities; (3) model and provide in-the-field telementoring to memory care coordinators.

To ensure compliance with the MIND protocol and quality of care, DCMS records for every participant are reviewed every 60 days by clinical supervisors. The interdisciplinary team also holds weekly care team rounds in which Memory Care Coordinators follow a template to present and discuss cases that (1) are particularly challenging or complex; (2) have had a critical event (e.g. hospitalizations, loss of care-giver); or (3) involve participants with low engagement.

Training and supervision

All team members complete a comprehensive 40 h training program on dementia followed by a practicum in the field. Training includes education on dementia and best practice principles, use of the dementia care needs assessment, dementia care management software, care plan development, care plan implementation and revision, critical events protocols (e.g. hospitalization), community resource identification and navigation, and engaging and rapport building with caregivers and persons with dementia. This initial training involves a range of disciplines (e.g. geriatric psychiatry, geriatric medicine, nursing, social work, OT) and includes didactic lectures, role playing, and observing assessments in clinical settings. Coordinators, RNs, and OTs role-play needs assessment evaluations, and assess and discuss case vignettes. Nurses and Memory Care Coordinators each observe and then lead observed screening assessments and demonstrate knowledge and skills proficiency on testing to become certified. Because the skills require time in the field to fully mature, team members receive ongoing monthly education on a range of topics including communication in dementia, nonpharmacological behavior management techniques, fall risk reduction, recognizing possible urinary tract infections, importance of nutrition and hydration, active listening, etc.

Under the HCIA award, the investigators have developed a comprehensive web-based training package consisting of eight modules for memory care coordinators and other team members to prepare the service delivery model for scalability and nationwide diffusion. The interactive e-learning format consists of a series of learning modules and knowledge evaluations that include didactic training with voice over PowerPoint, interactive content that asks learners to react to video clips of actual MIND at Home patients, and learner support tools (such as checklists, decision tables, flowcharts).

Measures

During the in-home visits (baseline, nine months, and 18 months) participant characteristics assessed include demographics, living arrangements, use of health care services and home and community-based supports (proxy reported), income, satisfaction with care, care financing, medications (brown-bag review, use and adherence survey), medical history and medical diagnoses (proxy reported), function (instrumental ADL and basic ADL), cognition (Mini-Mental State Exam), history of present illness and a brief physical exam (conducted by a clinician), and a home safety walkthrough. Caregiver characteristics assessed include demographics, marital status, employment, informal support networks, medical diagnoses, and use of health care services and home and community-based supports. These data inform the completion of the JHDCNA 2.0© and serve as covariates and risk-adjustment variables in the program impact evaluation.

Outcome measures for main aims completed at baseline, nine months, and 18 months by the memory care coordinators (nonblinded) include the JHDCNA 2.0©35 to assess dementia-related unmet care needs, QOL in AD54 to assess self-rated and proxy-rated QOL, Neuropsychiatric Inventory49 to assess dementia-related behavioral and mood symptoms, Zarit Burden Interview Short Form55 to assess subjective caregiver burden (objective and subjective), and the PHQ-956 to assess caregiver depressive symptoms. The JHDCNA 2.0© is a modified, shortened version of the original assessment developed earlier (JHDCNA 1.0©).35 JHDCNA 2.0© covers 13 domains, with 59 individual items (e.g. Cognitive Symptoms, Behavioral, Home and Personal Safety, Medical Care, Activities and Daily Living, Legal and Advanced Care Planning, Care Financing, Caregiver Dementia Education, Caregiver skills training, Caregiver Medical Care, Caregiver Mental Health Care, Caregiver Informal supports, Caregiver Legal Issues). Need items have standardized descriptions and definitions and each item on the JHDCNA is documented by trained staffed as being needed or not. If needed, the assessor determines whether the need is “fully met,” “partially met,” or “unmet.” A “fully met” need is one that is being addressed and potential benefits of available interventions have been achieved to the extent possible for the individual. A need is considered “partially met” if it has been or is being addressed but potential benefits of available interventions have not yet been achieved and “unmet” if it has not been addressed and potentially beneficial interventions are available. The JHDCNA was developed by a multidisciplinary group of clinical dementia care experts and is based on best practices in dementia care,23–28 suggesting content validity. While its psychometric properties have not been formally tested, prior studies demonstrate concurrent validity with QOL and care-giver burden measures.57,58 See Appendix 1 for more detail on the JHDCNA 2.0©.

Other health care and patient outcomes (patient and caregiver service satisfaction, acceptability of the program, barriers to care access) are evaluated at baseline, nine months, 18 months, and 24 months by the field evaluation team. Health care utilization and costs by participants are captured through Medicare and Medicaid claims data with a three-year look back period to establish baseline utilization and spending patterns, and continues through their enrollment in the study. Risk of institutionalization, time to institutionalization, utilization, and associated costs are defined and evaluated by source of care including inpatient, outpatient, medical provider, prescription drugs, skilled nursing facility, long-term nursing home care, HCBSs, assisted living, dental, and other services. The startup and operational cost of MIND at Home-Plus delivery is a critical adoption and sustainability outcome in this HCIA, and estimated by actual salary expenditures by staff type linked to time estimates for intervention activities. Intervention delivery characteristics (number of contacts, time spent per contact, care strategies used) are monitored continuously through a custom web-based care management software system previously developed in the MIND pilot randomized control trial, the DCMS.

Data analysis

A series of hypothesis-driven primary analyses will be carried out, with secondary analyses conducted as scientifically indicated. To determine the effectiveness of MIND at Home-Plus on risk of and time to nursing home LTC placement or death at 12, 18 (primary end point), and 24 months, compared to propensity-matched controls, we will fit Cox proportional hazards models for each time period with group assignment as the covariate of interest and adjustment for the matching variables. Model assumptions will be checked via Kaplan–Meier plots and Schoenfeld residuals. In secondary analyses we will explore the competing risks of death and care placement. To estimate total cost savings to the Medicare and Medicaid programs at 12, 18 (primary end point), and 24 months, compared to propensity-matched controls, we will perform interrupted time series analysis pre- and postintervention of participant group and comparison group to calculate cost savings (primary outcome). The main cost measure will be the cost offset of MIND-Plus, defined as the net financial benefit of the program to Medicare and Medicaid expenditures. This will be calculated as the difference in the sum of all costs between MIND-Plus group (including the cost of intervention delivery) and the sum of all costs in the propensity-matched comparison group from baseline to 18 months, adjusted for prior expenditures in the three-year period prior to enrollment in the service program or selection into the comparison group. To estimate within-group changes on dementia-related unmet care needs (total, domains), QOL, neuropsychiatric behaviors, as well as caregiver dementia-related unmet care needs (total, domains), subjective burden, objective burden, depression from baseline to nine months and 18 months (primary end point) for participants receiving MIND at Home-Plus, we will use repeated measures within subject tests. Risk adjustment for the payment model will include assessment of participant demographics (e.g. age), unmet care needs, cognitive impairment, comorbidities, and caregiver characteristics.

Discussion

Dementia represents an enormous public health challenge to the international community. Person-centered, evidence-based models of care that pragmatically link medical, social, and supportive care and services to assist persons with dementia and their family caregivers are critically needed to improve health outcomes, population health, and reduce care costs. Yet, many policy makers, health systems, and insurers lack the needed data on effectiveness, delivery and sustainability costs, and cost impacts to make decisions about adopting such models.

The MIND at Home-Plus dementia care coordination model represents one such potentially scalable model to help achieve these goals and is currently being delivered in a pragmatic HCIA-funded evaluation to 342 community-living persons with dementia in Maryland who are enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid or Medicare only. This project will provide timely and important new data on the impact of a novel community-based care coordination model among a highly vulnerable, high-cost population. To achieve sustainability and wider spread, the project will also carry out an ongoing evaluation of program costs and development of a payment model that could encourage a wide range of providers to adopt the MIND at Home model. Ongoing work will continue to develop a payment model including analysis of Medicare expenditures and utilization data; additional follow-up and analysis of Medicaid expenditures and utilization; and risk adjustment of the memory care coordination fee and shared savings for stage of cognitive impairment, comorbidities, and patient–caregiver relationships. Notwithstanding, this implementation study has important limitations in that it is not a randomized controlled trial, does not capture blinded outcomes, may not be generalizable to other settings and populations, and has a limited time frame for assessment of clinical and cost outcomes (up to 24 months) which may obscure longer term benefits and cost savings. Strengths of the MIND at Home-Plus model itself include its focus on the home as the nexus of dementia care coordination, its extensive needs assessment targeting both persons with dementia and their family caregivers at all stages of dementia, the manualized intervention protocol derived from best practices and evidence-based research, the economically efficient use of trained nonlicensed community workers (supported by geriatric psychiatrists, nurses) supporting development of a new dementia-competent workforce, and its proactive focus on optimization of person-centered outcomes (e.g. remaining at home for as long as possible, QOL). If proven effective and cost efficient, the MIND at Home model may serve as a nationally and potentially internationally scalable model with the potential to change how dementia care services are organized and provided at the community level.

Acknowledgments

The project described is supported by Grant Number 1C1CMS331332 from the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies. The authors sincerely thank the study participants and their families, the community partners, and the project’s supporters and funders.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This reserach was funded by Grant Number 1C1CMS331332 from the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (US) and by Grant Number R01AG046274 from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health (US).

Appendix 1

Overview and summary of the JHDCNA 2.0©

Overview of the JHDCNA 2.0©

The JHDCNA 2.0© is a multidimensional, manualized tool developed by a multidisciplinary group of clinical dementia experts through an iterative process based on best practices and research. It is intended for use by professionals and paraprofessionals who are trained in administration of the JHDCNA and involved in the delivery of community-based services for dementia participants and their caregivers. It includes seven care need domains of dementia care for persons with dementia (Sections A–G) and six care need domains of dementia care for caregivers (Sections H–M). Each of these domains includes a list of common dementia care needs relevant to that category. The original JHDCNA 1.0© contained 14 common care need domains for participants (71 individual items) and five common care domains for caregivers (15 items) but items were reduced in the revised version for simplicity, reduction of item overlap, and time efficiency.

The JHDCNA 2.0© instrument is formatted as a simple checklist with descriptors and anchor questions to help users identify unmet needs and provide notes. Users to first note which aspects of dementia care are needed by the individual based on a clinical assessment. Then, for each aspect of care needed, users can note whether that need is unmet, partially met, or fully met. While examples are provided in the JHDCNA manual for each individual need, determining the extent to which needs are met is left to the users’ clinical/professional judgments based on their assessment of each individual, taking into consideration the individual’s perspective on their needs. In general, however, a need is unmet if it has not been addressed at all and potentially beneficial interventions are available. A need is partially met if it has been or is being addressed but the potential benefits of the available interventions have not yet been fully achieved. A need is fully met if it has been or is being addressed and the potential benefits of the available interventions have been achieved to the extent possible for the individual.

The JHDCNA 2.0© manual provides specifications, descriptions for each need domain and individual need item, and detailed instructions on rating needs. It is assumed that clinicians who use the JHDCNA 2.0© have, at a minimum, specialized training in conducting an initial evaluation of individuals who have, or are suspected of having, dementia. It is also assumed that care coordinators who use this instrument are familiar, to some extent, with the community-based services that are available to persons with dementia and their caregivers in their local area. As such, the JHDCNA 2.0© manual is neither a training manual for professionals on how to provide dementia care, nor a comprehensive listing of resources. Rather, the JHDCNA 2.0© is a tool to facilitate the work of these professionals and the manual serves to orient them to the JHDCNA 2.0© tool and to provide guidance for determining whether unmet dementia-related needs exist based on the item definitions. Common abbreviations used in the manual are listed on the following page.

The organization of the JHDCNA 2.0© is as follows: The first seven sections (Section A–G) focus on identifying the care needs of the dementia participant or the individual at high risk for dementia. Sections A and B refer to needs related to memory and neuropsychiatric symptom management. Needs associated with general health care are in Section C. Home and personal safety and needs for daily living are in Sections D and E, respectively. Legal and advance care planning are in F. Section G lists needs associated with care financing. The needs of the participant’s caregiver—usually a family caregiver—are covered in the next six sections (Sections H–M) of the JHDCNA 2.0©. The first of these is Section H, which covers broad aspects of caregiver education. Section I focuses on the mental health care needs of caregivers, while general health care needs of the caregiver are listed in Section J. Informal support and daily living needs are in Sections K and L. Legal concerns are in Section M.

Total percent of unmet care needs based on the JHDCNA ((# of unmet need items/# need items assessed)*100) is determined and can be used as an outcome measure to indicate unmet care needs over time. If greater than 80% of the JHDCNA items are missing, we do not recommend calculation of the JHDCNA total percent score; however, individual need domain % unmet might be calculated as long as >80% is completed within each domain.

Examples from the JHDCNA 2.0 Tool©

| A. | Cognitive (memory and executive function) symptoms management: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needed | If yes, is need met | Notes | ||

| A-1 | Undiagnosed cognitive symptoms | |||

|

□Yes | □No | ||

| □No | □Partially | |||

| □Fully | ||||

| A-2 | Complex presentation of cognitive symptoms | |||

|

□Yes | □No | ||

| □No | □Partially | |||

| □Fully | ||||

| A-3 | Cognitive symptoms management | |||

|

□Yes | □No | ||

| □No | □Partially | |||

| □Fully | ||||

JHDCNA 2.0© domains and example items

| Domain | No. items | Item examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Symptom Management | 3 |

|

| Neuropsychiatric Symptoms Management | 5 |

|

| General Health Care | 10 |

|

| Home and Personal Safety | 10 |

|

| Daily living | 7 |

|

| Legal Concerns and Advance Care Planning | 4 |

|

| Care Financing | 4 |

|

| Caregiver Education | 8 |

|

| Caregiver Mental Health Care | 3 |

|

| General Health Care | 2 |

|

| Informal Support | 1 |

|

| Daily Living | 3 |

|

| Legal Concerns | 1 |

|

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Under a license agreement between Mind Halo, Inc. and the Johns Hopkins University, and Drs. Lyketsos, Black, and Johnston are entitled to royalties and equity on technology described in this publication. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. [Accessed May 10, 2017];Alzheimers Dement. 2017 13:325–373. http://www.alz.org/documents_custom/2017-facts-and-figures.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer Association. 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2016;12:1–80. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali G-C, et al. The worldwide costs of dementia 2015 and comparisons with 2010. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.07.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, et al. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;14368:1326–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thies W, Bleiler L, Assoc A. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures Alzheimer’s association. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:208–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaugler JE, Yu F, Krichbaum K, et al. Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Med Care. 2009;47:191–198. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818457ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black BS, Rabins PV, German PS. Predictors of nursing home placement among elderly public housing residents. Gerontologist. 1999;39:559–568. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.5.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287:2090–2097. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller EA, Weissert WG. Predicting elderly people’s risk for nursing home placement, hospitalization, functional impairment, and mortality: a synthesis. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:259–297. doi: 10.1177/107755870005700301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hébert R, Dubois MF, Wolfson C, et al. Factors associated with long-term institutionalization of older people with dementia: data from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M693–M699. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.11.m693. http://biomedgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/content/56/11/M693.full.pdf+html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper C, Bebbington P, Katona C, et al. Successful aging in health adversity: results from the National Psychiatric Morbidity survey. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:861–868. doi: 10.1017/S104161020900920X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller EA, Schneider LS, Rosenheck RA. Predictors of nursing home admission among Alzheimer’s disease patients with psychosis and/or agitation. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23:44–53. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connell CM, Janevic MR, Gallant MP. The costs of caring: impact of dementia on family caregivers. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2001;14:179–187. doi: 10.1177/089198870101400403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norton MC, Smith KR, Østbye T, et al. Increased risk of dementia when spouse has dementia? The Cache County study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:895–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Lyketsos CG. Nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms in dementia. JAMA. 2012;308:2020–2029. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.36918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of non-pharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:946–953. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper C, Mukadam N, Katona C, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions to improve quality of life of people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:856–870. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211002614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Health Quality O. Behavioural interventions for urinary incontinence in community-dwelling seniors: an evidence-based analysis. [accessed 24 November 2017];2008 8:1–15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3377527/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livingston G, Johnston K, Katona C, et al. Systematic review of psychological approaches to the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1996–2021. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dw O, Ames D, Gardner B, et al. Psychosocial treatments of psychological symptoms in dementia: a systematic review of reports meeting quality standards. IPG. 2009;21:241–251. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208008223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Neil ME, Freeman M, Christensen V, et al. A systematic evidence review of non-pharmacological interventions for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2011. [accessed 10 May 2017]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21634073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bond M, Rogers G, Peters J, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (review of Technology Appraisal No. 111): a systematic review and economic model. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16:1–470. doi: 10.3310/hta16210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Committee AGSCP. Guidelines abstracted from the American Academy of Neurology’s dementia guidelines for early detection, diagnosis, and management of dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:869–873. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyketsos CG, Colenda CC, Beck C, et al. Position statement of the American association for geriatric psychiatry regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:561–572. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221334.65330.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gould N. Guidelines across the health and social care divides: the example of the NICE-SCIE dementia guideline. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2011;23:365–370. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2011.606537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorbi S, Hort J, Erkinjuntti T, et al. EFNS-ENS guidelines on the diagnosis and management of disorders associated with dementia. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:1159–1179. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waldemar G, Dubois B, Emre M, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders associated with dementia: EFNS guideline. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:e1–e26. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rabins PV, Lyketsos CG, Steele C. Practical dementia care. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis K, Willink A, Schoen C. [accessed 9 June 2017];Medicare help at home. 2016 http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/04/13/medicare-help-at-home/

- 30.Willink A, Davis K, Schoen C. [accessed 27 October 2017];Improving benefits and integrating care for older medicare beneficiaries with physical or cognitive impairment. 2016 http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/issue-brief/2016/oct/1912_willink_improving_benefits_medicare_impairment_v4.pdf. [PubMed]

- 31.Callahan CM, Hendrie HC. Documentation and evaluation of cognitive impairment in elderly primary care patients. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:422. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-6-199503150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boustani M, Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, et al. Implementing a screening and diagnosis program for dementia in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:572–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaugler JE, Kane RL, Kane RA, et al. Unmet care needs and key outcomes in dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:2098–2105. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miranda-Castillo C, Woods B, Orrell M. The needs of people with dementia living at home from user, caregiver and professional perspectives: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:43. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Black BS, Johnston D, Rabins PV, et al. Unmet needs of community-residing persons with dementia and their informal caregivers: findings from the maximizing independence at home study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:2087–2095. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pimouguet C, Lavaud T, Dartigues JF, et al. Dementia case management effectiveness on health care costs and resource utilization: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14:669–676. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Somme D, Trouve H, Dramé M, et al. Analysis of case management programs for patients with dementia: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:426–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hickam DH, Weiss JW, Guise JM, et al. Outpatient case management for adults with medical illness and complex care needs. Comparative effectiveness review. [Accessed 24 November 2017];Comp Eff Rev. 2013 99:39–51. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/index.cfm/search-for-guides-reviews-and-reports/?pageaction=displayproduct&productid=1369. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tam-Tham H, Cepoiu-Martin M, Ronksley PE, et al. Dementia case management and risk of long-term care placement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28:889–902. doi: 10.1002/gps.3906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reilly S, Miranda-Castillo C, Malouf R, et al. Case management approaches to home support for people with dementia. In: Reilly S, editor. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Vol. 1. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2148–2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vickrey BG, Mittman BS, Connor KI, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:713. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00004. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=jlh&AN=2009348647&site=ehost-live. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menne HL, Bass DM, Johnson JD, et al. Program components and outcomes of individuals with dementia: results from the replication of an evidence-based program. J Appl Gerontol. 2017;36:537–552. doi: 10.1177/0733464815591212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samus QM, Johnston D, Black BS, et al. A multidimensional home-based care coordination intervention for elders with memory disorders: the maximizing independence at home (MIND) pilot randomized trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:398–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.12.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Possin KL, Merrilees J, Bonasera SJ, et al. Development of an adaptive, personalized, and scalable dementia care program: early findings from the care ecosystem. PLOS Med. 2017;14:e1002260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnston D, Samus QM, Morrison A, et al. Identification of community-residing individuals with dementia and their unmet needs for care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:292–298. doi: 10.1002/gps.2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanner JA, Black BS, Johnston D, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a community-based dementia care coordination intervention: effects of MIND at home on caregiver outcomes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:391–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. [accessed 22 May 2017];J Psychiatr Res. 1975 12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1202204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cummings JL. The neuropsychiatric inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology. 1997;48:S10–S16. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5_suppl_6.10s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilkinson IM, Graham-White J. Psychogeriatric dependency rating scales (PGDRS). A method of assessment for use by nurses. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;137:558–565. doi: 10.1192/bjp.137.6.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gitlin LN, Winter L, Vause Earland T, et al. The tailored activity program to reduce behavioral symptoms in individuals with dementia: feasibility, acceptability, and replication potential. Gerontologist. 2009;49:428–439. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gitlin LN, Winter L, Burke J, et al. Tailored activities to manage neuropsychiatric behaviors in persons with dementia and reduce caregiver burden: a randomized pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:229–239. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318160da72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, et al. A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers. JAMA. 2010;304:983. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, et al. Assessing quality of life in older adults with cognitive impairment. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:510–519. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, et al. The Zarit burden interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41:652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. [Accessed May 18, 2017];J Gen Intern Med. 2001 16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11556941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Black BS, Johnston D, Morrison A, et al. Quality of life of community-residing persons with dementia based on self-rated and caregiver-rated measures. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1379–1389. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0044-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hughes TB, Black BS, Albert M, et al. Correlates of objective and subjective measures of caregiver burden among dementia caregivers: Influence of unmet patient and caregiver dementia-related care needs. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:1875–1883. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214001240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]