Abstract

Malignant brain tumors represent one of the most devastating forms of cancer with abject survival rates that have not changed in the past 60 years. This is partly because the brain is a critical organ, and poses unique anatomical, physiological, and immunological barriers. The unique interplay of these barriers also provides an opportunity for creative engineering solutions. Cancer immunotherapy, a means of harnessing the host immune system for anti-tumor efficacy, is becoming a standard approach for treating many cancers. However, its use in brain tumors is not widespread. This review discusses the current approaches, and hurdles to these approaches in treating brain tumors, with a focus on immunotherapies. We identify critical barriers to immunoengineering brain tumor therapies and discuss possible solutions to these challenges.

Keywords: Brain Cancer, Immunotherapy, Blood-Brain Barrier, Lymphatics, Tumor-Associated Microglia, Neuroimmunology, Glioblastoma, Neurooncoimmunology, Immunoengineering, immunomodulation

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Brain and nervous system cancers represent only a small proportion of annual cancer incidence (1.4%) yet these cancers represent almost double that proportion (2.7%) of cancer deaths [1]. Neuroepithelial tumors represents the vast majority of malignant brain tumors, the most common of which, glioblastoma (46%), incurs a mere 5% of patients surviving beyond 5 years [2]. This dismal survival rate results from the utter lack of available therapies that can both navigate anatomical barriers and not adversely impact delicate neuronal tissue.

Current clinical standard of care for brain tumors is maximal safe surgical resection, followed by concomitant fractionated radiotherapy, and chemotherapy (oral Temozolomide, and/or implanted Carmustine wafer) [3]. Surgical resection, however, is not always possible due to the location of the tumor corresponding to sensitive or inoperable regions of the brain [4,5]. Further, recurrence after surgery is common, as many brain tumors have invasion fronts that penetrate into healthy tissue beyond the primary tumor core, making it often impossible to remove all malignant cells [6]. Systemic chemotherapy is also less efficacious in the treatment of brain tumors, as the ability for these drugs to efficiently reach some brain tumor tissues is hindered by the transport-restrictive properties of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), adaptive resistance to the drug, exacerbation of side effects due to increased effective dose requirements and sensitivity of neural tissue, and an inability to fully obliterate resident tumor renewing populations [7–9]. Even with all the continued advances in drug discovery and delivery that have improved substantially improved outcomes in systemic cancers, there has been disappointingly little impact on tumors of the brain.

Immunotherapies have the potential to mitigate some of the challenges involved with treating tumors in the brain, but are not yet part of the standard of care. Targeting inside the brain has proven difficult, but through modulations of the immune system, one may be able to take advantage of natural routes of entry, and the capacity of the immune system’s memory to prevent further recurrence after a standard treatment regime could lead to improved outcomes in brain cancer. One striking piece of evidence for the potential of immunotherapy for brain neoplasms is that brain cancers that metastasize and disseminate into the extra-neural immune system (which is exceedingly rare) may lead to slightly more favorable outcomes [10]. Further, Volovitz, et al. showed, in immune-competent rats, that the mere transplantation of an aggressive brain tumor into the periphery was sufficient to confer an anti-tumor effect in the brain [11]. This suggests that there is grand opportunity for immune-driven therapies in brain cancer. Apart from the non-trivial nature of the design of immunotherapies, engineering such a therapy for brain tumors may require more complexity, as the brain poses unique anatomical and physiological constraints on successful implementation. In the following sections we will discuss the unique anatomy and physiology of the brain and malignant brain tumors, and the relevant challenges with respect to designing, engineering, and administering immunotherapies.

2. NeuroImmune Anatomy & Physiology

Broadly speaking, brain parenchyma fundamentally consists of neurons and glial cells. The glial cells are further categorized as astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia; the microglia being the resident innate immune cell of the central nervous system (CNS). Microglia perform a number of critical functions including cytotoxicity, phagocytosis, and T-cell activation through antigen presentation [12]. The parenchyma of the brain is covered by three meningeal layers: the dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater. The dura mater is the outermost layer (attached to the skull) and the pia mater is the innermost layer (Fig. 1A). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), produced by choroid plexus cells in the ventricles, bathes the brain parenchyma and flows in the subarachnoid space (the space between the pia mater and arachnoid mater). Immunity in the CNS is very tightly regulated, and during homeostasis, T-cells and other myeloid cells that reside in the meningeal layers, exert their immunogenic effects from there [13,14]. One way to understand neuroimmunology is to embrace the concept that the purpose of the immune reaction in CNS pathology is to allow neurons to function undisturbed.

Figure 1. The Brain Tumor/Neuro-Immune Environment.

(a) Brain parenchymal barriers to peripheral immune cells. The Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB), Blood-Meningeal Barrier (BMB), and the Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier (BCSF) all actively prevent blood borne cells from entering the brain parenchyma. When a brain tumor occurs, the BBB is breached and blood-borne signals and immune cells can more readily infiltrate the brain. (b) Simplified overview of immune-suppressed cellular regulation in brain tumors.

There are three critical barriers that prevent peripheral moieties from entering the brain parenchyma. These are the blood-brain barrier (BBB, a physiologically active barrier between brain parenchymal vasculature and brain parenchyma); the blood-meningeal barrier (BMB, a physiological cellular barrier between the meningeal blood vessels and the meninges), and the choroid plexus barrier (also called the blood-CSF barrier that prevents entry of blood borne moieties into the ventricular CSF) [13,15,16] (Fig. 1A). During homeostasis, the BBB, BMB, and BCSFB may limit the entry of particular pathogens and leukocytes while abluminally promoting immune cell interactions [13,15,17]. In terms of relative permissibility, the BBB is the most selective barrier, followed by the BMB and the BCSFB. This is due to the vascular organization of the three barriers. For example, in the BCSFB and the BMB, the endothelial cells are fenestrated, allowing immune cells to easily cross them [13,15–17].

During homeostasis, blood-borne immune cells do not cross the BBB [13,14,18]. In pathological states, however, the primary entry site of immune cells is via the meningeal blood vessels, across the BMB, into the pia to infiltrate the brain parenchyma using a variety of mechanisms, not all of which are fully understood [13]. During infection, pathogens may initially gain access to the CSF across vessels within the meninges and ventricular system, due to the fenestrated endothelium [13,14]. However, the meningeal arachnoid membrane and ventricular choroid plexus epithelial cells have intercellular tight junctions that help restrict the invasion of pathogens into the CNS parenchyma [15–17]. The circulating CSF in these compartments then aids in detection of pathogens via meningeal CSF sampling [13,19,20]. Recently, confirmed presence of meningeal lymphatic vessels and glymphatics (interstitial fluid clearance via aquaporins on glial cells) seem to represent an important exit route for immune cells (and macromolecules) from the CNS and/or CSF [19–21]. The way into the CNS and/or the CSF is still a matter of debate [13].

During trauma, infection, or other neurological disorders, both the innate and adaptive immune systems are recruited through the various routes listed above. It is important to note that the immune (peripheral) system and the CNS are not orthogonal but are closely intertwined, regulated and monitored by each other [18,22]. While initial entry of blood-borne immune cells is usually neuroprotective, prolonged residence of these cells is harmful and can lead to neurological dysfunction, autoimmunity and neurodegeneration [13,23–25]. Therefore, the regulation of the immune response is critical in the CNS. When the blood-CNS barriers are broken and blood borne cells enter the CNS parenchyma, both cell types might react in ways that are ‘unnatural’ for them, leading to irregular production of cytokines, chemokines, danger signals, etc., manifesting in a breakdown in neuronal communication and ultimately resulting in symptoms such as depression and other behavioral deficits [26].

3. Neuro-Onco-Immunology

The pathological neuroimmune response that occurs during a malignant brain tumor elicits a cellular milieu that is heterogeneous and variable, made up of a complex network of immune-activating and immune-tempering cells (Fig. 1B). Higher grade brain tumors lead to exacerbated irregular vascularization, BBB disruption, tumor necrosis, and antigen expulsion [27–30] (Fig. 1A). As noted above, the fenestration of the BBB, and in this case its disruption, is important for attraction and invasion of immunomodulatory cells from the periphery. All this contributes to increased presence of immune cells in the tumor bed, but not necessarily better survival outcomes. Importantly, though the BBB is considered ‘leaky’ in many brain tumors, inside the tumor core an intact BBB is present across large regions, presenting barriers for drug delivery and immunotherapy [31].

The malignant cells within a single neuroepithelial tumor will often evolve into a diverse set of phenotypes over time with respect to immunogenicity, immune evasion, and resistance. Microglia, macrophages, dendritic cells and various lymphocytes have all been shown to infiltrate brain tumor tissues [12,32]. Yet, whether many of these cells arise from parenchymal or peripheral sources is unknown. Further, it is unclear whether the myeloid cells infiltrating brain tumor tissues are a cause or consequence of tumor progression. While CNS antigens can reach the peripheral lymph nodes [33], it is unknown whether antigen cross-presentation of brain tumor antigens happens centrally or peripherally. Antigen-presentation has not been fully characterized in the brain, though DCs, microglia (though, when activated express less MHC than DC), and pericytes (cells that enshroud the vascular endothelial cells in the BBB) are known to be involved [34–36]. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the immune cell infiltration in neuroepithelial tumors is relatively sparse when compared to other tumors. In the following subsections, we provide a brief overview highlighting the unique immune cohort present in the Neuro-Onco-Immune environment.

3.1 Brain-Tumor-Associated Myeloid-Derived Cells

Both brain-resident microglia and peripheral macrophages are known to infiltrate brain tumors. In fact, there is a positive correlation between the number of tumor-associated macrophages and microglia, and brain tumor grade [12]. Brain-tumor-associated macrophages and microglia lack co-stimulatory molecules and secretory factors for T-cell activation, and present immunosuppressive signals (e.g., PDL1, FASL) [28,37,38]. Recently, Gabrusiewicz, et al. showed that a higher proportion of microglia and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) were among the tumor-associated myeloid-derived cells than macrophages, and that the overall spectrum of phenotypes did not fit well the canonical M1/M2 model of microglia/macrophage activation [39]. The functional role of MDSCs in the brain tumor immune response has yet to be discovered, though they do elicit phenotypic features similar to canonically-activated macrophages [40].

Dendritic cells (DCs) are also found in the brain tumor microenvironment, yet their immune function is typically stunted [41–43]. Normal DCs secrete IFNα leading to T-cell maturation, while brain tumor associated DCs elicit no IFNα secretion [43]. The increased VEGF concentrations in and around brain tumors, not only aids in recruitment of monocytes to the tumor, but is also known to disrupt DC and monocyte maturation [38,44]. Monocyte-derived DC from brain glioma patients (stimulated with IFNα & CSF2) have been shown to be functionally impaired, though it is still unknown whether these cells are pathogenic [45].

3.3 Brain-Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes

Brain cancer microenvironments are known to attract infiltration of naive cytotoxic T-cells (CD8+) and T-helper cells (CD4+) and to actively modulate their phenotypes [46–48]. The ratio of infiltrated CD8+ to CD4+ T-cells is a prognostic indicator in brain tumors. CD8+ T-cells confer an anti-tumor response, while CD4+ T-cells appear to regulate the tumor-associated microglia/macrophage phenotype toward a more tumor-supportive one. However, T-cell function overall is paralyzed by common cytokines expressed in the tumor microenvironment (e.g., VEGF, TGFβ, IL10, PGE2, etc.) [30,32,41]. Impaired T-cells have lower proliferation and an overall attenuated response to pro-inflammatory signals, leading to overall down-regulation of major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs) and DC maturation [32,49]. Additionally, T-cell apoptosis, is driven by expression of CD70/CD27 and gangliosides in the brain tumor microenvironment, as well as microglial expression of PDL1 and FasL [50–53].

In many high-grade brain tumors, there is also a massive infiltration of regulatory T-cells (Tregs) via tumor-secreted chemokines (e.g., CCL22, TGFβ) [54–56]. When fully activated, Tregs can suppress proliferation and the cytokine-production of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, leading to a more aggressive brain tumor. Depletion of Tregs in mice has been shown to prolong survival and lead to non-immunosuppressive myeloid cell infiltration [57]. Natural Killer (NK) and B cells are also present, but unlike many systemic tumors these are found at relatively low abundance, and NK cells in particular are natively suppressed in brain neoplasms [27,58].

3.4 Brain Cancer Cells

Brain cancer cells employ multiple strategies to reprogram innate and adaptive immunity to evade cell death. These may include recruitment of immunosuppressive cells such as Tregs, potent modulation of immune checkpoints (e.g., the PD1–PDL1 axis), and/or ineffective tumor antigen presentation (e.g., down-regulate their own MHC I), making them immune-invisible and leading to a reduced inflammatory cytokine profile (e.g., decreased IL12 & IFNγ; increased IL10, VEGF, TGFβ & PGE2) [28,32,59,60].

Additionally, brain cancer stem cells (BCSC), the subclass of self-renewing, tumorigenic cancer cells, can also contribute to this immunomodulatory response (e.g., secretion of periostin for increased recruitment of tumor-supportive microglia and macrophages) [61–64]. BCSCs are important in driving and sustaining long term tumor growth through the production of transient populations of highly proliferative cells can aid in tumor invasion and provide therapeutic resistance [65,66]. Furthermore, BCSCs, like non-cancerous stem cells, are also highly immunomodulatory: BCSCs can attenuate immune surveillance within the tumor microenvironment and further aid tumor development by the secretion and expression of immunosuppressive cytokines and receptors [67]. Recent work by Alvarado, et al. [68] has shown that BCSCs in GBM are capable of evading attack by the innate immune system, mainly by altering their immunogenicity via the down-regulation of toll-like receptor 4, thus avoiding immune-mediated rejection in vivo. Clearly, targeting BCSCs to prevent tumor recurrence is an important and critical therapeutic target, nevertheless, it is difficult to trace and track BCSCs with precision. As we learn more about the properties of BCSCs and refine methods for isolating and tracing these cells, novel therapeutic targets for GBM might become available.

Apoptosis and necrosis of brain cancer cells also produces an important set of factors to the tumor-immune microenvironment: danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [69–71]. Many of these DAMPs are dual-edged, contributing to antigen-recognition and adjuvancy, as well as tumor progression, and can have complex relationships to overall prognosis. For example, the combination of increased calreticulin (which is important for DC recognition of dying tumor cells, but is also related to increased angiogenesis and tumor cell proliferation), increased HSP70 (which can be cross-presented by DCs to CD8+ T-cells, and has critical roles in tumor initiation and progression), and decreased HMGB1 (a classical danger signal, but also pro-angiogenic) has been shown to correlate to an improved prognosis in glioblastoma (GBM) [71]. Much work remains to fully characterize the entire cadre of danger signals, but their importance as both biomarkers and in shaping the brain tumor immune response should not go unnoticed when considering immunotherapies.

4 Current Therapies

Several clinical studies have been conducted in recent years that have targeted key players of the Neuro-Onco-Immune environment. In fact, cancer immunotherapy approaches in brain have had some limited success [72,73]. However, applying immunotherapy to the brain exposes certain challenges. For example, a healthy BBB restricts drug delivery to the brain, and while the brain tumor environment tends to have leaky vasculature that facilitates drug access [74], the elevated interstitial pressure of fluid can hamper therapeutics infiltration [75]. Additionally, the poorly understood lymphatics of brain could potentially lead to ineffective immunotherapeutic delivery to target cells as well as a non-uniform immunological response. The brain also has its own unique contingent of immune cells where not only resident cells contribute to the immunological function, but also the peripheral response varies regionally. Moreover, there are overall fewer immune cells and thus relatively few antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the brain during cancer. Lastly, even when there may be a desired anti-cancer immune response, due to the sensitivity of neuropil, side effects that induce neurotoxicity and autoimmunity during immunotherapeutics are always of concern.

Since immunotherapy for the treatment of brain tumors has been heavily reviewed [73,76,77], in this paper we focus on the most current and late stage clinical trial therapies, and the engineering challenges these immunotherapies face in brain tumor environment. Relevant clinical trials for brain tumor immunotherapy were found using search parameters on National Institute of Health Clinical Trial database (ClinicalTrials.gov) (see Suppl. Table 1). Of the 439 clinical trials, 106 were started January 2016 and onwards or later than Phase II. Of the surveyed trials, about 7% represented active or completed Phase III or IV trials, which clearly demonstrates a challenge progressing to later stage clinical trials.

In the following subsections, we briefly discuss available cancer immunotherapies and provide selected examples of their use in treating brain tumors. Additionally, for each, we highlight how the design of each does not necessarily address the particular difficulties of treating brain neoplasms.

4.1 Vaccines

Traditional vaccines against viral diseases (e.g., influenza) use attenuated or live virus along with a danger signal (as adjuvant) to activate DCs. DCs then take up the viral antigen, process it, migrate through lymphatic vessels to lymph nodes, and then activate T-cells through presentation of diverse peptide antigens/antigenic epitopes on MHC molecules. T-cells consequently expand into short-lived effector and long-lived memory populations to not only respond to the foreign antigen immediately, but also to develop immunity for later antigen re-encounter. Although a small portion of cancer vaccines work in a preventive way (e.g. hepatocellular and cervical carcinoma), a large number of cancer vaccines are classified in the therapeutic category (e.g. GBM) [78]. In general, these therapeutic cancer vaccines encounter more challenges as the nature of tumor and host immune response coevolve in a complex fashion [79].

Overall, the cancer vaccines being extensively developed broadly encompass peptide, dendritic cell, tumor cell, and neoantigen vaccines [80]. Within brain tumors, vaccines with various adjuvants, delivery mechanisms, and combination strategies have displayed therapeutic potential with limited adverse events [81]. Importantly, the use of adjuvant is crucial in an immune privileged environment such as the brain, as the lack of resident immune cells in the brain could hinder this immune response. Ergo, vaccines are being developed and improved to adapt to the immunosuppressed brain tumor environment. Below, we discussed two main subcategories of brain cancer vaccine: peptide vaccines, and dendritic cells vaccines.

4.1.1 Peptide Vaccines

Peptide vaccines (Fig. 2) induce a T-cell response at the tumor site by releasing peptides specific to tumor-associated antigens. Peptides, commonly coupled with carrier proteins and adjuvants, are taken up by APCs and presented on the cell surface by MHC molecules. In humans, MHC I molecules are known as human leukocyte antigens (HLA). [82] APCs navigate the lymphatic system to prime T-cells, which then recognize the tumor cell from its antigen [83]. Antigen expression varies across tumors and characterizing the antigenic repertoire for each tumor is a significant challenge, though attempts have been made to uncover novel glioma antigens for new therapeutics [79,84–86].

Figure 2.

Vaccine-based immunotherapy for brain tumors.

As an example of a peptide vaccine in use for brain tumors, Rindopepimut is designed to target the overexpressed Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 7 (EGFRvIII) antigen on EGFRvIII+ brain tumor cells. However, this vaccine did not alter overall survival during a Phase III clinical trial [87], and the tumors of relapsed patients lacked the EGFRvIII antigen [88]. Despite the fact that this therapy only targets a subset of patients with EGFRvIII+ tumors [89], the heterogeneous, evolutionary nature of brain tumors leads to tumor cells without the EGFRvIII antigen to be untargeted and thus allowed to propagate [90,91].

To address the problem of heterogeneously-expressed tumor-associated antigens, the IMA950 multi-peptide vaccine contains 11 HLA-restricted tumor-associated peptides [92]. A Phase I trial of IMA950 reported an overall survival of 13.2 months with no injection site reaction vs. 26.7 months with an injection site reaction, however, the median age of the injection site reaction groups was significantly lower [93].

For patients without common tumor cell antigens, autologous peptide vaccines are being developed to target patient specific tumor antigens. One such vaccine for glioma, GAPVAC-101, is currently undergoing early safety and feasibility studies [94].

Apart from tumor heterogeneity and evolution, the main challenges of peptide vaccines are getting sufficient peptides to APCs and the subsequent immune response cascade, which in the brain is further exacerbated by both the presence of the BBB and a lack of resident APCs. Increasing APC recruitment to the injection site has been explored with various adjuvants, however, engineering a sustained recruitment of APCs prior to and during vaccination could hold promising therapeutic potential (e.g., with a slow-release hydrogel eluting APC recruitment factors).

4.1.2 Dendritic Cell Vaccines

Cancer vaccination can also be achieved by direct activation of DCs ex vivo (Fig. 2). Instead of injecting a peptide that is presented to an APC, immunotherapy strategies for cancer have used autologous dendritic cells sourced from peripheral blood monocytes primed with tumor associated antigens [95]. Immature DCs can uptake and process antigens, and in the presence of inflammatory signals, immature DCs mature, thus becoming capable of proper antigen presentation for T-cell recognition in a MHC-restrictive manner [96]. These mature DCs are then reinjected into the patient where they home to a secondary lymph node in order to activate T-cells. Activated CD8+ T-cells can now recognize a tumor cell by its specific antigen and MHC I complex, and will attempt to lyse the recognized cell. Since DC vaccine stimulation happens ex vivo, the DCs can be activated much more effectively than peptide vaccines in situ, as they are exposed to the cell lysate from tumor biopsies with a broad pool of antigens [79].

To date, many different formulations of DC vaccines have already entered clinical trials for use in brain tumors [96,97]. For example, ICT-107 is an autologous DC vaccine pulsed with six tumor-associated antigens that was evaluated for use with recurrent glioblastoma. A ten-year follow-up of a Phase I ICT-107 vaccine trial identified 19% of 16 patients disease free for 8 years with a median overall survival of 38.4 months. There was a correlation of survival with cancer-stem-cell-associated expression of targeted antigens and increased CD8+ T-cell responses [98]. A Phase II trial using this approach for glioblastoma targeted the pp65 antigen using a tetanus and diphtheria (Td) vaccine booster to stimulate the immune system. This method has been observed to enhance DC migration by significantly increasing the percentage of DCs homing to the lymph node via preconditioning with Td booster injection [99].

Although DC vaccines can surmount many of the issues faced by peptide vaccines with respect to antigen selection, the main challenge in their use is one of optimizing efficacy. DC vaccine efficacy is low since the time of action is relatively short, and only small fraction of the DCs migrate to and eventually reach the lymph nodes after injection. The Td-preconditioning work by Mitchell, et al., exhibits the potential of a strategy that hijacks native mechanisms of immune cell recruitment [99]. Though, in brain tumors, further optimization and innovation remains particularly challenging, as the barriers to entry of CNS lymphatics, and consequent antigen presentation and cytotoxic T-cell response are not fully understood. Even if the activated DCs are reintroduced locally to the tumor in order to rely on endogenous triggering of this process, it is unclear whether the DC/T-cell interaction, upon which DC vaccines rely, is the most suitable given lack of understanding of antigen presentation in the neuro-immune cohort.

4.2 Adoptive Cell Therapy

Instead of relying on DC activation, in Adoptive Cell Therapy (ACT) (Fig. 3), T-cells and various other Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs) can be directly activated [100,101]. In the simplest form of ACT, isolated TILs from tumor biopsies are expanded – based on the assumption that these TILs are tumor specific – before being injected into the patient and eventually homing back to the tumor [79]. These autologous strategies rely on a patient’s own immune response and an understanding of the lymphatic architecture of the tissue where the tumor resides.

Figure 3.

Adoptive Cell Therapy for brain tumors.

Cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells and Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells are the two of the most commonly used TILs in ACT. CIK cells come from peripheral blood lymphocytes induced in vitro with IFNγ, IL2, and CD3 monoclonal antibodies [102]. CAR T-cells are engineered to connect intracellular activation to an extracellular domain specific to a single or multiple costimulatory tumor-associated antigens [101]. Both CIK cell and CAR T-cells provide MHC-unrestrictive antigen recognition and are thus advantageous for use in ACT, and both are have found use in clinical trials for GBM.

In a Phase III randomized trial for GBM using intravenous injection of autologous CIK cells with concomitant Temozolomide yielded a marked, but not statistically significant 5.6 month increase in median survival relative to standard of care [102]. Preliminary results from a Phase I trial of CAR T-cells (in this study engineered to target the GBM tumor antigen IL13Rα2) reported safe intracranial delivery and detection of the CAR T-cells for a minimum of 7 days in the tumor cyst fluid or CSF. A subset of these patients exhibited a decrease in IL13Rα2 antigen expression, and in one particular patient, a >79% regression of recurrent tumor mass was observed [103].

Despite these hints at a successful therapeutic avenue, T-cell therapy faces not only the technical and manufacturing challenges that any autologous cell therapy faces (e.g., ex vivo expansion, complete and persistent induction of cytotoxic phenotype, etc.), but also all the challenges that cellular vaccine therapies face mentioned above. Overall, these cancer immunotherapies can kill both cancer and normal cells, especially when the antigen recognized by these immune cells is specifically related to a cell type that cancer cells derived from. This is of particular importance when considering immunotherapies in the brain, since many peripheral immune cells that have homed to a brain tumor site will be immunologically naive to the CNS cellular cohort. Moreover, if intravenous delivery is the route of choice, the BBB integrity is a crucial limiting factor for autologous cell delivery.

4.3 Monoclonal Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies (Fig. 4) represent a passive form of immunotherapy that does not necessarily involve the body’s immune system. Antibodies can be administered either as naked, where the target pathway is simply disrupted, or conjugated with a therapeutic agent as a drug targeting modality, or an antibody designed to stimulate an anti-tumor response by the immune system (e.g., a bi-specific antibody that also recognizes the Fc receptor) [104]. Antibodies are typically chosen that target surface receptors that are abnormally, and highly expressed in tumors or receptors involved in tumorigenesis.

Figure 4.

Monoclonal Antibody Therapy for brain tumors.

For brain tumors, EGFR, or its mutant EGFRvIII, are commonly overexpressed in GBM cells and are the most common target for antibody-based therapies for GBM. For example, ABT-414 is an antibody-drug conjugate that can target either EGFR or EGFRvIII and when attached to a cell can deliver a potent anti-microtubule toxin. Current phase I studies for ABT-414 for newly diagnosed GBM patients have elicited a median progression free survival of 6.1 months and a 6-month progression free survival of 25.3% for recurrent GBM [105,106].

Another monoclonal antibody that has been extensively used in brain tumors, Nimotuzumab, is an anti-EGFR inhibitor that has been used in combination with irinotecan in pediatric high grade gliomas yet has only incurred a slight improvement in overall survival [107].

The subpar survival benefits to monoclonal antibody therapy use in the brain are primarily attributed to their inability to cross the BBB without significant barrier disruption, as well as patient-specific mutations in target antigens that alter antibody-binding efficacy. Further, antibody-based strategies for selectively immune-targeting tumor cells in the brain, have not been well explored, and may generally suffer from the lack of NK cells for antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity or macrophages for antibody-directed phagocytosis.

4.4 Checkpoint Inhibition

Immune checkpoint therapy (Fig. 5) functions by blocking inhibitory pathways that attenuate the normal activity of cytotoxic T-cells and can be used alone to bolster the native immune response, or to increase the response of tandem therapies that would otherwise be immune-inhibited [108]. In tumors, cancer cells will express proteins that interact with co-inhibitory receptors on T-cells (e.g., PD1 and CTLA4) [109]. Antibodies manufactured to block these receptors are currently being developed as a brain tumor therapy, as well as strategies to block the presentation of their inhibitory ligands (e.g., PDL1 on DCs, macrophages and tumor cells) [110].

Figure 5.

Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy for brain tumors.

PD1 expression has already been established as a clinical marker for TIL activation and (dys)function in GBM, as PD1+ TILs have increased clonality compared to PD1- populations [111]. Nivolumab, an antibody for the PD1 receptor, has been tested with concurrent Temozolomide and radiotherapy for safety in a Phase I trial for GBM, reporting limited adverse events [112].

A strategy targeting CTLA4 has also been trialed for use in GBM. Ipilimumab is an anti-CTLA4 monoclonal antibody, indicated for use with bevacizumab and concomitant adjuvants, that showed a partial response in 40% of patients. Preliminary 1-year data show that 44% of the 16 patients surviving, which is an improvement on the 37% 1-year survival rate expected in GBM [2,113].

Checkpoint inhibitor delivery to the brain is hindered just as any other drug delivery scheme would be; the BBB remains a critical boundary, impermissive to systemic drug delivery. Even with sufficient inhibitor at the brain tumor site, it is unclear whether the inhibition would be sufficient to overcome all the immunosuppression rampant in the tumor bed, and whether sufficient cytotoxic T-cells could be disinhibited and their anti-tumor activity sustained at therapeutic levels. Further, because the blockade of these checkpoint pathways is not antigen specific, a patient undergoing these treatments becomes prone to the development of autoimmune disease and inflammation, which spells disaster for a functional neuronal environment [114].

4.5 Virotherapy

Oncolytic virotherapy (Fig. 6) makes use of nonpathogenic viruses to selectively invade or specifically express proteins in brain tumor cells that can directly kill cancer cells or otherwise stimulate an immune response [115–117].

Figure 6.

Oncolytic Virotherapy for brain tumors.

One particularly promising virotherapy indicated for brain tumors is Ad-RTS-hIL-12, an inducible adenoviral vector that expresses IL12 in the presence of an orally-administered activator ligand, veledimex. In a Phase I dose escalation study, done in patients with high-grade gliomas, it was shown that the veledimex could efficiently cross the BBB and reach the tumor bed (at up to 46% of administered concentration) and that there was a dose-dependent relationship between veledimex administered and concentration in the tumor [118]. This early treatment study also showed increases of serum IL12 and consequent increased IFNγ concentration, as well as increased number of CD8+ T-cells in circulation, with minimal reported neurotoxicities, and an impressive 100% 6-month survival for the 13 patients thus far.

Another virotherapy design of note, is the use of a poliovirus chimera, PVSRIPO, that selectively replicates, and induces cell lysis in CNS tumor-originating cells, but not in healthy neuronal cells [119]. A Phase I clinical trial of PVSRIPO for recurrent GBM produced overall safe and effective results, with 10 of 13 patients still alive at the end of the trial [120].

Many virotherapy methods have been explored, yet challenges remain for their general application in the brain. The attenuated immune response in the brain provides the possibility that a viral response relying on inflammatory signaling may be either ineffective, as the targeted effector cells can still be subsequently inhibited, or not present in sufficiently therapeutic concentrations at the tumor site. Or worse, the inflammatory triggers are overly robust, and may cause immune cells to run rife among and disrupt the healthy neuronal cohort. Additionally, the targeting of cells of non-neuronal lineage may make a strategy like PVSRIPO inviting, however, other constituent cells in the CNS may be mistaken for cancer cells and this may lead to detrimental side effects.

Virotherapy for brain tumors also relies heavily on viral migration to the tumor site, which can be inhibited by the BBB. Migration of the virus to the tumor site is circumvented by intratumoral injection, but this is not always feasible in brain tumors, particularly when they are disseminated through the CNS, or lack a central, primary core (for instance during recurrence).

5. Opportunities for Engineers to Address Challenges of Brain Cancer Immunotherapy

While some of the advances in immunotherapy clinical trials for brain cancers are promising, many hurdles remain before those immunotherapies can be standard of care for difficult to treat brain tumors such as GBM. Some of these challenges are broadly applicable to all cancer immunotherapies throughout the body. For example, the heterogeneity posed by individualized immune systems makes patient-agnostic immunotherapies among large target populations difficult. Also, as mentioned above, depending on the domain or epitope recognized by immune cells, these immunotherapies could potentially target healthy cells that share tumor-associated antigens.

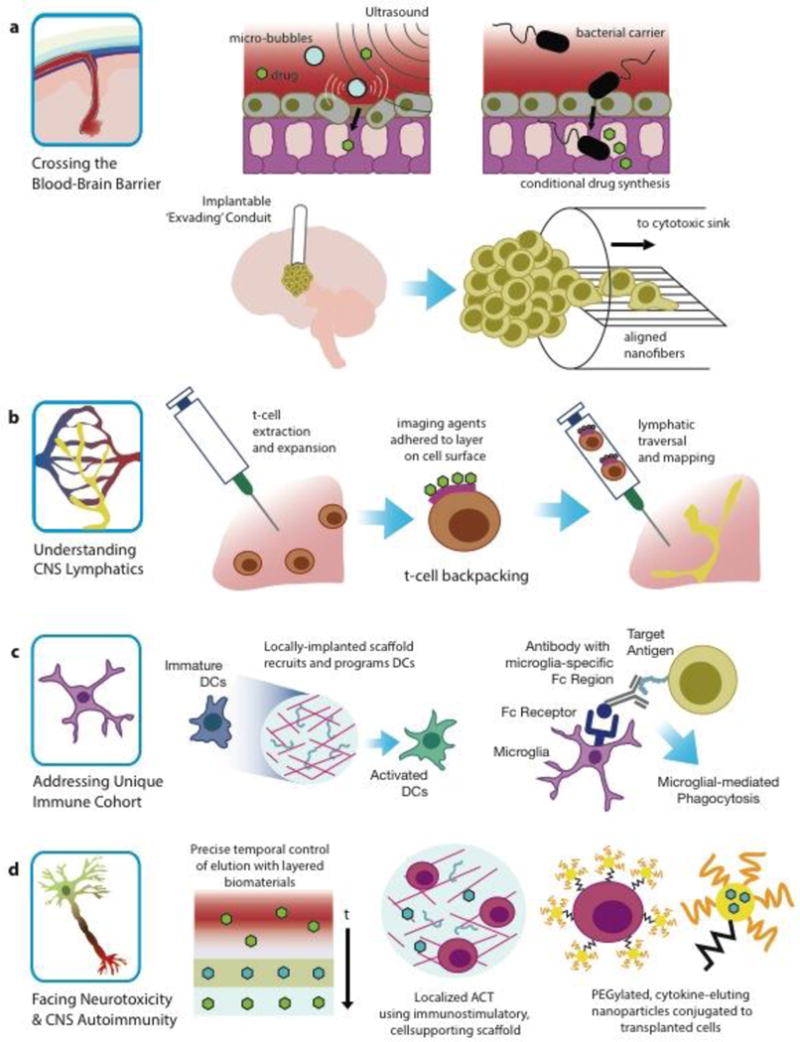

There remain, however, additional challenges when treating tumors in the brain with immunotherapies. In this section, we consider 4 pressing challenges, unique to neuroepithelial brain tumors (Fig. 7), namely: i) hindered systemic access to the brain via the blood-brain barrier; ii) a poorly understood lymphatic vessels; iii) the unique immune cohort of brain; and iv) the sensitivity of neural tissue and possibilities of neurotoxicity and/or triggering autoimmune diseases. Below we discuss some potential engineering solutions that could address these brain-unique challenges as this field moves on toward translating the principles of cancer immunotherapy for brain into clinical reality.

Figure 7.

Engineering strategies to address challenges of brain cancer immunotherapies.

5.1 Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier

In order to reach nefarious brain tumor infiltrates, and to surmount the heterogeneity posed by the irregular leakiness of the BBB, unique solutions need to be explored. Many of the ingenious, out-of-the-box solutions under development for targeting tumors across neurobiological boundaries are ripe for integration into immunotherapeutic concepts. The vast library of available engineered materials and systems may also be important to consider for the potential to enhance delivery of immunomodulatory therapies to the brain.

The need for crossing the BBB to present immunomodulatory signals could be bypassed by using nanoparticle systems that can coopt existing signaling pathways. For example, immune-cell inspired nanoparticles can target, locally activate a biological cascade, and consequently broadcast tumor location to amplify tumor targeting of diagnostic or therapeutic cargo-carrying nanoparticles [121].

Physically breaching the BBB may be another route of access, for example, by reversibly doing so using pulsed ultrasonic sound waves, which has been shown to effectively enhance intracortical drug concentrations (Fig. 7a), is already a clinically-available option for glioma [122]. Temporary disruption of the BBB by using pulsed ultrasound combined with injected microbubbles can further optimize the delivery of a chemotherapeutic to the brain in patients with recurrent GBM [122]. Circumvention of the BBB can also be achieved by using engineered constructs to redirect tumor invasion into areas that allow for more facile intervention. For example, white matter-mimicking nanofibers (Fig. 7a) can be placed adjacent to a GBM tumor, providing a preferential path for GBM cell migration, and thus guiding those invasive cells away for the primary tumor site to an extra-cortical location for further treatment [123].

Use of bacteria or stem cells [124,125], is especially enticing, as they both offer a programmable approach to crossing the blood-brain barrier (Fig. 7a) and to tumor-homing, and possess the advantage of being readily programmable for the sensing of a tumor microenvironment and the production and/or presentation of immunomodulatory factors. The genetic capacity of these cells may also afford more subtle and complex variations of genetic immunotherapy than the above-mentioned viral therapies.

These methods circumvent some of the physiological and anatomical barriers posed by the BBB and the brain, and in fact take advantage of the inherent properties of brain tumors and the associated cellular milieu to improve therapeutic efficacy and outcomes.

5.2 Improving our Understanding of CNS Lymphatics

One reason for the immune-privilege status of the brain was the apparent lack of lymphatics, yet this view has been recently upended [19–21]. Because this is a new discovery, there is ample room for creative use of bioengineering and biological engineering to take advantage of existing brain lymphatics, or to engineer synthetic lymphatics that can guide glial tumors to deep cervical lymph nodes to increase T-cell mediated anti-tumor immunity; lymphatics that not only facilitate transport of tumor-associated antigens to immune cells, but that also enable more immediate access to the tumor for matured, tumor-killing T-cells. Indeed, in other peripheral tumors the presence of lymphatic vessels results in retardation of tumor growth and increased activated T-cell infiltrates [126]. Interestingly, lymph node-like vasculature, the major portal for naïve T-cell infiltration, can be developed by tumors [126]. Use of existing technologies like T-cell backpacking [127] and DC vaccines [128] can potentially leverage the discovery of brain lymphatics to improve therapeutic efficacy. The idea behind T-cell backpacking (Fig. 7b) is to use polyclonal T-cells that express lymph node-homing receptors, to shepherd various chemical cargo (e.g., immunostimulatory or chemotherapeutic drugs, imaging agents, etc.) throughout the lymphoid tissues [127]. Especially in therapeutic modalities for brain tumors where antigen presentation to T-cells is required, targeting brain-draining lymph nodes is likely a promising approach to bolster an endogenous anti-tumor immune response.

However, unique antigens of brain tumors remain uncharacterized, and it is unclear whether brain tumors drain antigens to deep cervical lymph nodes. The literature on the lymphatic architecture in GBM is sparse, possibly due to the hitherto lack of knowledge of CNS lymphatics. However, the recent discovery of the glymphatic and lymphatic systems of the brain [19–21] now provides new means to control immunity within the brain and we foresee this as an exciting avenue for brain tumor therapies.

5.3 Addressing the Unique Immune Cohort in Brain Tumors

For a long time, the CNS had been considered an immunologically-privileged site, based on the fact that engrafted tissues into the brain are rejected more slowly than in other sites [129]. However, today the CNS is more accurately described as immunologically “distinct”, due to multiple unique characteristics of its immune cohort including inherent expression of immunosuppressive cytokines, such as TGFβ and IL10, low level expression of MHCs, lack of APCs, and the presence of the BBB [129]. While T-cells and antibodies have access to antigens within the CNS, and therefore gliomas, lack of enough APCs within brain tumor microenvironment may affect the efficiency of some immunotherapies including vaccines. Overall, immunotherapy in GBM has not produced significantly positive results compared to other cancers such as prostate cancer, melanoma, or renal cell carcinoma. Besides constitutive expression of immunosuppressive agents in brain and brain tumors, the utter lack of available APCs may attribute to these disappointing results.

One possible approach to address this constraint is to use a biomaterial-based vaccine. Macroporous matrices could be used in the context of vaccine immunotherapy, such that the matrices regulate the trafficking and activation of DCs and their monocyte precursors in situ (Fig. 7c) [130]. Implantable matrices that were fabricated from poly(lactide-co-glycolide) and enriched with GM-CSF, a CpG oligonucleotide (ODN), and tumor lysates (to provide presentation of cytokines, DAMPs, and tumor-associated antigens) were shown to spatiotemporally recruit and activate DCs in a glioma model [131]. This study demonstrated that the coordinated, intracranial presentation of multiple immune-stimulatory factors from these biodegradable matrices implanted into the tumor surrounding tissue, resulted in tumor regression and enhanced long-term survival in an otherwise fatal model. Moreover, this treatment resulted in formation of long-term immunological memory causing attenuation in progression of a secondary glioma-cell challenge.

Further exploration of antibody-based strategies for brain cancer may also be warranted, as the role of Fc receptors in the brain, particularly with respect to antibody-mediated microglial phagocytosis, becomes clearer. Fc receptors in the brain are often associated with a neurodegenerative response, and have been linked to conditional cellular responses in the CNS, e.g., in inflammation, aging, or Alzheimer’s disease [132,133]. Through use of antibody-based strategies to take into account the particular Fc receptors that elicit particular neurodegenerative responses may allow for a neuro-onco-degenerative response directed specifically toward antibody targeted cells (Fig. 7c).

Targeting of the BCSC population may also provide novel avenues to immunotherapies, as in the context of brain tumors this has not been extensively explored. It is widely believed that the small, non-immunogenic, and treatment-resistant population of cancer stem cells is responsible for the majority of traditional anti-angiogenic or anti-proliferative treatments [67]. Despite limited ongoing clinical trials, there are no FDA-approved immunotherapies that directly target cancer stem cells. It is becoming increasingly important to further understand the characteristics that distinguish BCSC from the non-stem tumor cells from the perspective of immune evasion in order to further advance immunoengineering therapies that can mitigate the therapy-resistant properties of these cells.

5.4 Facing Neurotoxicity and CNS Autoimmunity

The brain, unlike other organs such as the skin or prostate, cannot tolerate even the smallest level of autoimmunity. Moreover, due to presence of the rigid skull, brain environment is very much edema-intolerant [129]. Considering the sensitivity of the neuropil, the precision of immunotherapy is notably critical. This precision includes not only enhancing the specificity toward the target, but also improving the spatiotemporal delivery of the agents. Biomaterials-based strategies show tremendous promise in both of these two areas [134]. Biomaterials can provide highly versatile tools to create desirable immune microenvironments and to deliver agents in order to manipulate cells and tissues. Spatiotemporal delivery of immunomodulators (Fig. 7d) using biomaterials can provide enhanced safety and efficacy in any cancer immunotherapy, not just in the brain. Moreover, as biomaterials can be designed to encompass multiple functions, they could potentially be used to impact immune signaling pathways at many stages against many targets in myriad ways.

Biomaterial-based vaccines, for example, may result in more precise immune-modulation, as they not only control the delivery of adjuvants and antigens spatiotemporally, but also regulate trafficking of immune cells and mimic stimulatory signals of innate immunity through their chemical and physical characteristics [135]. Biomaterials can also help by maintaining the viability and functionality of transplanted cells, such as in ACT, by providing desirable cytokine presentation in the cellular microenvironment (Fig. 7d) [135]. For instance, systemic administration of cytokines such as IL15 and IL2 has been shown to improve the persistence of the transplanted T-cells, yet their high-dose can cause severe side effects to the brain tissue [135–137]. Stephan, et al. developed a nano-carrier loaded with cytokine and conjugated to the surface of the transplanted cells that can be used to avoid the detrimental effects to the brain tissue, yet still provide ‘pseudoautocrine’ signals to maintain the therapeutic cells (Fig. 7d) [138].

6. Conclusion

Malignant brain tumors represent one of the most devastating forms of cancer with abject survival rates that have not changed in the past 60 years – a result largely due to lack of available therapies that can both navigate anatomical barriers and not adversely impact delicate neuronal tissue. The rapid advances in cancer immunotherapies represent a promising frontier in the potential treatment of these otherwise inoperable tumors. However, while immunotherapy approaches have shown promising results in other cancers, little progress has been made for brain tumors.

The brain is a critical organ, and it imposes unique anatomical, physiological, and immunological barriers to successful treatment. These unique anatomical & physiological constraints lead to intrinsic engineering challenges for developing therapies that necessarily act within the brain and brain tumor immune microenvironment. To date, engineering approaches to applying immunotherapies in the brain, beyond simply re-acquisitioning of existing extra- Antibody neural immunotherapies, are lacking; the opportunities, however, are ample. By considering at therapeutic approaches from an engineering perspective, we may be able to leverage more variety of technologies in order to advance tailored treatment strategies that can address the particular biological constraints of treating within the brain, thus enabling better brain cancer immunotherapies.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Clinical trial search terms

| Tumor Type Term | Modality Term | Additional 3rd Terms | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glioma | + | Vaccine | Peptide, Autologous, Dendritic Cell, Tumor Lysate, Heat Shock Protein, Cytomegalovirus, Personalized |

| Medulloblastoma | Checkpoint | PD-1, CTLA4, IDO, CD27 | |

| Meningioma | Virus | ||

| Oligodendroglioma | Adoptive | Lymphokine, Lymphocyte, Natural Killer, Chimeric Antigen Receptor, Stem Cells | |

| Ependymoma | Antibody |

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (7R01NS093666, 5R01NS065109). The authors also acknowledge funding from Ian’s Friends Foundation and The Billie and Bernie Marcus Foundation.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Adoptive Cell Therapy

- APC

Antigen-Presenting Cell

- BBB

Blood-Brain Barrier

- BMB

Blood-Meningeal Barrier

- BCSC

Brain Cancer Stem Cells

- BCSFB

Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier

- CAR

Chimeric Antigen Receptor

- CCL22

C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 22

- CIK

Cytokine-Induced Killer

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- CSF

Cerebrospinal Fluid

- CSF2

Colony Stimulating Factor 2

- CTLA4

Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Associated Protein 4

- DAMP

Danger-Associated Molecular Pattern

- DC

Dendritic Cell

- EGFR

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- FASL

Fas Ligand

- GBM

Glioblastoma

- HLA

Human Leukocyte Antigen

- HMGB1

High Mobility Group Box 1

- HSP70

Heat Shock Protein Family A

- IFNα

Interferon Alpha

- IFNγ

Interferon Gamma

- IL#

Interleukin #

- IL13Rα2

Interleukin 13 Receptor Subunit Alpha 2

- MDSC

Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell

- MHC

Major Histocompatibility Complex

- NK

Natural Killer

- PD1

Programmed Cell Death Protein 1

- PDL1

Programmed Death-Ligand 1

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- Td

Tetanus and Diptheria

- TGFβ

Transforming Growth Factor Beta

- TIL

Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte

- Treg

Regulatory T-cell

- VEGF

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental Table Methods For ‘Supplemental Table.xlsx’

A combination of tumor type and type of immunotherapy and intervention guided search parameters applied on The National Institute of Health Clinical Trial database (ClinicalTrails.gov) between February 22nd and March 1st 2017 (Table 1). Additional search parameters were applied based on literature review to encompass all trials for a specific intervention and all duplicates were removed.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2013. 2016:1992–2013. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975%7B_%7D2013/results%7B_%7Dmerged/sect%7B_%7D24%7B_%7Dstomach.pdf.

- 2.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Farah P, Ondracek A, Chen Y, Wolinsky Y, Stroup NE, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-sloan JS. CBTRUS Statistical Report : Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2006–2010. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:iv1–iv62. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nabors LB, Portnow J, Ammirati M, Baehring J, Brem H, Brown P, Butowski N, Chamberlain MC, Fenstermaker RA, Friedman A, Gilbert MR, Hattangadi-Gluth J, Holdhoff M, Junck L, Kaley T, Lawson R, Loeffler JS, Lovely MP, Moots PL, Mrugala MM, Newton HB, Parney I, Raizer JJ, Recht L, Shonka N, Shrieve DC, Sills AK, Swinnen LJ, Tran D, Tran N, Vrionis FD, Weiss S, Wen PY, McMillian N, Engh AM. Central nervous system cancers, version 1.2015: Featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. JNCCN J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2015;13:1191–1202. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0435-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricard D, Idbaih A, Ducray F, Lahutte M, Hoang-Xuan K, Delattre JY. Primary brain tumours in adults. Lancet. 2012;379:1984–1996. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiesner SM, Freese A, Ohlfest JR. Emerging concepts in glioma biology: implications for clinical protocols and rational treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19:E3. doi: 10.3171/foc.2005.19.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellail AC, Hunter SB, Brat DJ, Tan C, Van Meir EG. Microregional extracellular matrix heterogeneity in brain modulates glioma cell invasion. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1046–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rostomily RC, Spence AM, Duong D, McCormick K, Bland M, Berger MS. Multimodality management of recurrent adult malignant gliomas: results of a phase II multiagent chemotherapy study and analysis of cytoreductive surgery. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:378–88. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199409000-00004. discussion 388. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7800129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beier D, Röhrl S, Pillai DR, Schwarz S, Kunz-Schughart LA, Leukel P, Proescholdt M, Brawanski A, Bogdahn U, Trampe-Kieslich A, Giebel B, Wischhusen J, Reifenberger G, Hau P, Beier CP. Temozolomide preferentially depletes cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5706–5715. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blakeley J. Drug delivery to brain tumors. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s11910-008-0036-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pietschmann S, von Bueren AO, Kerber MJ, Baumert BG, Kortmann RD, Müller K. An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis on Characteristics, Treatments and Outcomes of Glioblastoma/Gliosarcoma Patients with Metastases Outside of the Central Nervous System. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volovitz I, Marmor Y, Azulay M, Machlenkin A, Goldberger O, Mor F, Slavin S, Ram Z, Cohen IR, Eisenbach L. Split immunity: immune inhibition of rat gliomas by subcutaneous exposure to unmodified live tumor cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:5452–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hambardzumyan D, Gutmann DH, Kettenmann H. The role of microglia and macrophages in glioma maintenance and progression. Nat Neurosci. 2015;19:20–27. doi: 10.1038/nn.4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kipnis J. Multifaceted interactions between adaptive immunity and the central nervous system. Science. 2016;80(353):766–771. doi: 10.1126/science.aag2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein RS, Garber C, Howard N. Infectious immunity in the central nervous system and brain function. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ni.3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbott NJ. Dynamics of CNS barriers: evolution, differentiation, and modulation. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25:5–23. doi: 10.1007/s10571-004-1374-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbott NJ, Patabendige AAK, Dolman DEM, Yusof SR, Begley DJ. Structure and function of the blood–brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008;57:178–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. Neural regulation of immunity: molecular mechanisms and clinical translation. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20 doi: 10.1038/nn.4477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Louveau A, Smirnov I, Keyes TJ, Eccles JD, Rouhani SJ, Peske JD, Derecki NC, Castle D, Mandell JW, Lee KS, Harris TH, Kipnis J. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature. 2015;523:337–341. doi: 10.1038/nature14432. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature14432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aspelund A, Antila S, Proulx ST, Karlsen TV, Karaman S, Detmar M, Wiig H, Alitalo K. A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J Exp Med. 2015;212:991–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg Ba, Peng W, Gundersen Ga, Benveniste H, Vates GE, Deane R, Goldman SA, Nagelhus EA, Nedergaard M, A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes Including Amyloid. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:147ra111–147ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, Yang H, Botchkina GI, Watkins LR, Wang H, Abumrad N, Eaton JW, Tracey KJ. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature. 2000;405:458–62. doi: 10.1038/35013070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwab JM, Zhang Y, Kopp Ma, Brommer B, Popovich PG. The paradox of chronic neuroinflammation, systemic immune suppression, autoimmunity after traumatic chronic spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2014;258:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popovich PG, Longbrake EE. Can the immune system be harnessed to repair the CNS? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:481–93. doi: 10.1038/nrn2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rivest S. Regulation of innate immune responses in the brain. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:429–39. doi: 10.1038/nri2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller AH, Haroon E, Felger JC. Therapeutic Implications of Brain–Immune Interactions: Treatment in Translation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:334–359. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang I, Han SJ, Sughrue ME, Tihan T, Parsa AT. Immune cell infiltrate differences in pilocytic astrocytoma and glioblastoma: evidence of distinct immunological microenvironments that reflect tumor biology. J Neurosurg. 2011;115:505–11. doi: 10.3171/2011.4.JNS101172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charles NA, Holland EC, Gilbertson R, Glass R, Kettenmann H. The brain tumor microenvironment. Glia. 2012;60:502–514. doi: 10.1002/glia.21264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dubois LG, Campanati L, Righy C, D’Andrea-Meira I, de SE Spohr TCL, Porto-Carreiro I, Pereira CM, Balça-Silva J, Kahn SA, DosSantos MF, de AR Oliveira M, Ximenes-da-Silva A, Lopes MC, Faveret E, Gasparetto EL, Moura-Neto V. Gliomas and the vascular fragility of the blood brain barrier. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:418. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Domingues P, González-Tablas M, Otero Á, Pascual D, Miranda D, Ruiz L, Sousa P, Ciudad J, Gonçalves JM, Lopes MC, Orfao A, Tabernero MD. Tumor infiltrating immune cells in gliomas and meningiomas. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;53:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Tellingen O, Yetkin-Arik B, de Gooijer MC, Wesseling P, Wurdinger T, de Vries HE. Overcoming the blood–brain tumor barrier for effective glioblastoma treatment. Drug Resist Updat. 2015;19:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Razavi SM, Lee KE, Jin BE, Aujla PS, Gholamin S, Li G. Immune Evasion Strategies of Glioblastoma. Front Surg. 2016;3:11. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2016.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laman JD, Weller RO. Drainage of cells and soluble antigen from the CNS to regional lymph nodes. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:840–856. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9470-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kostianovsky AM, Maier LM, Anderson RC, Bruce JN, Anderson DE. Astrocytic regulation of human monocytic/microglial activation. J Immunol. 2008;181:5425–5432. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ribeiro AL, Okamoto OK. Combined effects of pericytes in the tumor microenvironment. Stem Cells Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/868475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perng P, Lim M. Immunosuppressive Mechanisms of Malignant Gliomas: Parallels at Non-CNS Sites. Front Oncol. 2015;5:153. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bloch O, Crane CA, Kaur R, Safaee M, Rutkowski MJ, Parsa AT. Gliomas promote immunosuppression through induction of B7-H1 expression in tumor-associated macrophages. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3165–3175. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kennedy BC, Showers CR, Anderson DE, Anderson L, Canoll P, Bruce JN, Anderson RCE. Tumor-associated macrophages in glioma: Friend or foe? J Oncol. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/486912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gabrusiewicz K, Rodriguez B, Wei J, Hashimoto Y, Healy LM, Maiti SN, Thomas G, Zhou S, Wang Q, Elakkad A, Liebelt BD, Yaghi NK, Ezhilarasan R, Huang N, Weinberg JS, Prabhu SS, Rao G, Sawaya R, Langford La, Bruner JM, Fuller GN, Bar-Or A, Li W, Colen RR, Curran Ma, Bhat KP, Antel JP, Cooper LJ, Sulman EP, Heimberger AB. Glioblastoma-infiltrated innate immune cells resemble M0 macrophage phenotype. JCI Insight. 2016;1:1–32. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.85841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Umemura N, Saio M, Suwa T, Kitoh Y, Bai J, Nonaka K, Ouyang GF, Okada M, Balazs M, Adany R, Shibata T, Takami T. Tumor-infiltrating myeloid-derived suppressor cells are pleiotropic-inflamed monocytes/macrophages that bear M1- and M2-type characteristics. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1136–1144. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grauer OM, Wesseling P, Adema GJ. Immunotherapy of diffuse gliomas: Biological background, current status and future developments. Brain Pathol. 2009;19:674–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D’Agostino PM, Gottfried-Blackmore A, Anandasabapathy N, Bulloch K. Brain dendritic cells: Biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:599–614. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1018-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dey M, Chang AL, Miska J, Wainwright DA, Ahmed AU, Balyasnikova IV, Pytel P, Han Y, Tobias A, Zhang L, Qiao J, Lesniak MS. Dendritic Cell-Based Vaccines that Utilize Myeloid Rather than Plasmacytoid Cells Offer a Superior Survival Advantage in Malignant Glioma. J Immunol. 2015;195:367–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gabrilovich DI, Chen HL, Girgis KR, Cunningham HT, Meny GM, Nadaf S, Kavanaugh D, Carbone DP. ion of dendritic cellsProduction of vascular endothelial growth factor by human tumors inhibits the functional maturation of dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:1096–103. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tyrinova TV, Leplina OY, Mishinov SV, Tikhonova MA, Shevela EY, Stupak VV, Pendyurin IV, Shilov AG, Alyamkina EA, Rubtsova NV, Bogachev SS, Ostanin AA, Chernykh ER. Cytotoxic activity of ex-vivo generated IFNalpha-induced monocyte-derived dendritic cells in brain glioma patients. Cell Immunol. 2013;284:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dunn GP, Dunn IF, Curry WT. Focus on TILs: Prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in human glioma. Cancer Immun. 2007;7:12. doi:081043 [pii] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han S, Zhang C, Li Q, Dong J, Liu Y, Huang Y, Jiang T, Wu A. Tumour-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes as predictors of clinical outcome in glioma. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2560–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sayour EJ, McLendon P, McLendon R, De Leon G, Reynolds R, Kresak J, Sampson JH, Mitchell DA. Increased proportion of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in tumor infiltrating lymphocytes is associated with tumor recurrence and reduced survival in patients with glioblastoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64:419–427. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1651-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Albesiano E, Han JE, Lim M. Mechanisms of Local Immunoresistance in Glioma. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2010;21:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wischhusen J, Jung G, Radovanovic I, Beier C, Steinbach JP, Rimner A, Huang H, Schulz JB, Ohgaki H, Aguzzi A, Rammensee H, Weller M. Identification of CD70-mediated apoptosis of immune effector cells as a novel immune escape pathway of human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2592–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11980654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shurin GV, Shurin MR, Bykovskaia S, Shogan J, Lotze MT, Barksdale EM. Neuroblastoma-derived gangliosides inhibit dendritic cell generation and function. Cancer Res. 2001;61:363–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11196188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Magnus T, Schreiner B, Korn T, Jack C, Guo H, Antel J, Ifergan I, Chen L, Bischof F, Bar-Or A, Wiendl H. Microglial Expression of the B7 Family Member B7 Homolog 1 Confers Strong Immune Inhibition: Implications for Immune Responses and Autoimmunity in the CNS. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2537–2546. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4794-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Badie B, Schartner J, Prabakaran S, Paul J, Vorpahl J, Leonard EJ, French L, Van Meir EG, de Tribolet N, Tschopp J, Dietrich PY, Tschopp J. Expression of Fas ligand by microglia: possible role in glioma immune evasion. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;120:19–24. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(01)00361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grauer OM, Nierkens S, Bennink E, Toonen LWJ, Boon L, Wesseling P, Sutmuller RPM, Adema GJ. CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells gradually accumulate in gliomas during tumor growth and efficiently suppress antiglionia immune responses in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:95–105. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jacobs JFM, Idema AJ, Bol KF, Grotenhuis JA, de Vries IJM, Wesseling P, Adema GJ. Prognostic significance and mechanism of Treg infiltration in human brain tumors. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;225:195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crane CA, Ahn BJ, Han SJ, Parsa AT. Soluble factors secreted by glioblastoma cell lines facilitate recruitment, survival, and expansion of regulatory T cells: Implications for immunotherapy. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:584–595. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maes W, Verschuere T, Van Hoylandt A, Boon L, Van Gool S. Depletion of regulatory T cells in a mouse experimental glioma model through Anti-CD25 treatment results in the infiltration of non-immunosuppressive myeloid cells in the brain. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/952469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kmiecik J, Zimmer J, Chekenya M. Natural killer cells in intracranial neoplasms: Presence and therapeutic efficacy against brain tumours. J Neurooncol. 2014;116:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1265-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vinay DS, Ryan EP, Pawelec G, Talib WH, Stagg J, Elkord E, Lichtor T, Decker WK, Whelan RL, Kumara HMCS, Signori E, Honoki K, Georgakilas AG, Amin A, Helferich WG, Boosani CS, Guha G, Ciriolo MR, Chen S, Mohammed SI, Azmi AS, Keith WN, Bilsland A, Bhakta D, Halicka D, Fujii H, Aquilano K, Ashraf SS, Nowsheen S, Yang X, Choi BK, Kwon BS. Immune evasion in cancer: Mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35:S185–S198. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nduom EK, Weller M, Heimberger AB. Immunosuppressive mechanisms in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(Suppl 7):vii9–vii14. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Di Tomaso T, Mazzoleni S, Wang E, Sovena G, Clavenna D, Franzin A, Mortini P, Ferrone S, Doglioni C, Marincola FM, Galli R, Parmiani G, Maccalli C. Immunobiological characterization of cancer stem cells isolated from glioblastoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:800–813. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu A, Wei J, Kong LY, Wang Y, Priebe W, Qiao W, Sawaya R, Heimberger AB. Glioma cancer stem cells induce immunosuppressive macrophages/microglia. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:1113–1125. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lathia J, Mack S, Mulkearns-Hubert E, Valentim C, Rich J. Cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1203–1217. doi: 10.1101/gad.261982.115.tumors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou W, Ke SQ, Huang Z, Flavahan W, Fang X, Paul J, Wu L, Sloan AE, McLendon RE, Li X, Rich JN, Bao S. Periostin secreted by glioblastoma stem cells recruits M2 tumour-associated macrophages and promotes malignant growth. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:170–182. doi: 10.1038/ncb3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, Henkelman RM, Cusimano MD, Dirks PB. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03031.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen J, Li Y, Yu TS, McKay RM, Burns DK, Kernie SG, Parada LF. A restricted cell population propagates glioblastoma growth after chemotherapy. Nature. 2012;488:522–526. doi: 10.1038/nature11287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Silver DJ, Sinyuk M, Vogelbaum MA, Ahluwalia MS, Lathia JD. The intersection of cancer, cancer stem cells, and the immune system: Therapeutic opportunities. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18:153–159. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alvarado AG, Thiagarajan PS, Mulkearns-Hubert EE, Silver DJ, Hale JS, Alban TJ, Turaga SM, Jarrar A, Reizes O, Longworth MS, Vogelbaum MA, Lathia JD. Glioblastoma Cancer Stem Cells Evade Innate Immune Suppression of Self-Renewal through Reduced TLR4 Expression. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:450–461.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Curtin JF, Liu N, Candolfi M, Xiong W, Assi H, Yagiz K, Edwards MR, Michelsen KS, Kroeger KM, Liu C, Muhammad a KMG, Clark MC, Arditi M, Comin-Anduix B, Ribas A, Lowenstein PR, Castro MG. HMGB1 Mediates Endogenous TLR2 Activation and Brain Tumor Regression. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krysko O, Løve Aaes T, Bachert C, Vandenabeele P, Krysko DV. Many faces of DAMPs in cancer therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e631. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Muth C, Rubner Y, Semrau S, Rühle P-F, Frey B, Strnad A, Buslei R, Fietkau R, Gaipl US. Primary glioblastoma multiforme tumors and recurrence. Strahlentherapie Und Onkol. 2016;192:146–155. doi: 10.1007/s00066-015-0926-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fecci PE, Heimberger AB, Sampson JH. Immunotherapy for Primary Brain Tumors: No Longer a Matter of Privilege. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5620–5629. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tivnan A, Heilinger T, Lavelle EC, Prehn JHM. Advances in immunotherapy for the treatment of glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11060-016-2299-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Iyer AK, Khaled G, Fang J, Maeda H. Exploiting the enhanced permeability and retention effect for tumor targeting. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goel S, Duda DG, Xu L, Munn LL, Boucher Y, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Normalization of the vasculature for treatment of cancer and other diseases. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:1071–121. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00038.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang B, Zhang H, Gu L, Ye B, Jian Z, Stary C, Xiong X. Advances in Immunotherapy for Glioblastoma Multiforme. J Immunol Res. 2017;2017:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2017/3597613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dunn-Pirio AM, Vlahovic G. Immunotherapy approaches in the treatment of malignant brain tumors. Cancer. 2016:1–17. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Melero I, Gaudernack G, Gerritsen W, Huber C, Parmiani G, Scholl S, Thatcher N, Wagstaff J, Zielinski C, Faulkner I, Mellstedt H. Therapeutic vaccines for cancer: an overview of clinical trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:509–24. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jeanbart L, Swartz Ma. Engineering opportunities in cancer immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:14467–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508516112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wong KK, Li WWA, Mooney DJ, Dranoff G. Advances in Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines. 1st. Elsevier Inc.; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xu LW, Chow KKH, Lim M, Li G. Current vaccine trials in glioblastoma: A review. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/796856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Comber JD, Philip R. MHC class I antigen presentation and implications for developing a new generation of therapeutic vaccines. Ther Adv Vaccines. 2014;2:77–89. doi: 10.1177/2051013614525375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li W, Joshi M, Singhania S, Ramsey K, Murthy A. Peptide Vaccine: Progress and Challenges. Vaccines. 2014;2:515–536. doi: 10.3390/vaccines2030515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Swartz AM, Batich KA, Fecci PE, Sampson JH. Peptide vaccines for the treatment of glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2015;123:433–440. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1676-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu G, Ying H, Zeng G, Wheeler CJ, Black KL, Yu JS. HER-2, gp100, and MAGE-1 are expressed in human glioblastoma and recognized by cytotoxic T cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4980–4986. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Akiyama Y, Komiyama M, Miyata H, Yagoto M, Ashizawa T, Iizuka A, Oshita C, Kume A, Nogami M, Ito I, Watanabe R, Sugino T, Mitsuya K, Hayashi N, Nakasu Y, Yamaguchi K. Novel cancer-testis antigen expression on glioma cell lines derived from high-grade glioma patients. Oncol Rep. 2014;31:1683–1690. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Weller M, Butowski N, Tran D, Recht L, Lim M, Hirte H, Ashby L, Mechtler L, Goldlust S, Iwamoto F, Drappatz J, O’Rourke D, Wong M, Finocchiaro G, Perry J, Wick W, He Y, Davis T, Stupp R, Sampson J. ATIM-03. Act IV: An international, double-blind, phase 3 trial of rindopepimut in newly diagnosed, EGFRvIII-expressing glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18:vi17–vi18. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now212.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sampson JH, Heimberger AB, Archer GE, Aldape KD, Friedman AH, Friedman HS, Gilbert MR, Herndon JE, McLendon RE, Mitchell DA, Reardon DA, Sawaya R, Schmittling RJ, Shi W, Vredenburgh JJ, Bigner DD. Immunologic escape after prolonged progression-free survival with epidermal growth factor receptor variant III peptide vaccination in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4722–4729. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.6963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Verhaak RGW, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, Miller CR, Ding L, Golub T, Mesirov JP, Alexe G, Lawrence M, O’Kelly M, Tamayo P, Weir BA, Gabriel S, Winckler W, Gupta S, Jakkula L, Feiler HS, Hodgson JG, James CD, Sarkaria JN, Brennan C, Kahn A, Spellman PT, Wilson RK, Speed TP, Gray JW, Meyerson M, Getz G, Perou CM, Hayes DN. Integrated Genomic Analysis Identifies Clinically Relevant Subtypes of Glioblastoma Characterized by Abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]