Abstract

Objective

To measure and identify the determinants of the outcomes after hip/knee arthroplasty (HA/KA) in patients with osteoarthritis during the first postsurgical year.

Design

In this prospective observational study, we evaluated the preoperative and postoperative (3, 6, and 12 months) outcomes of 626 patients who underwent HA (346 with median age 65 years, 59% female) or KA (280 with median age 66.5 years, 54% female) between 2008 and 2013. Generic and specific tools were used to measure health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and utility. Good outcome was defined as an improvement in WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) greater than or equal to the minimal important difference (MID). Regressions were performed to evaluate the relationship between preoperative and postoperative measures and evolution of WOMAC/good outcome.

Results

We observed an almost systematic improvement of all parameters for up to 12 months, but especially at the 3-month follow-up. The low number of comorbidities and the absence of postoperative complications were the common determinants of improvement of WOMAC total score after 12 months. Other parameters (background of the joint, preoperative function and length of hospital stay in KA group; place of discharge in HA group) affected the evolution of WOMAC scores. 87.09% of HA and 73.06% of KA patients experienced a good outcome. A small number of comorbidities, a worse preoperative function, a shortened hospital stay (KA only), and an absence of early postoperative complications (HA only) significantly predicted a good outcome.

Conclusions

Intermediate HRQoL following HA or KA improved quickly from preoperative levels for all instruments. More than 70% of patients achieved a good outcome defined as improved pain, stiffness and disability and the predictors are slightly close.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, hip, knee, arthroplasty, quality of life

Introduction

Aging of the population worldwide has led to a rise in chronic degenerative diseases, including osteoarthritis (OA). Osteoarthritis may affect up to 40% of people aged older than 65 years in the community. Symptomatic osteoarthritis is present in 9% of men and 11% of women, with an estimated incidence in the knee of 240 per 100,000 patients-years and 88 per 100,000 patient-years in the hip. Among developed countries, OA is 1 of the 3 most disabling conditions with a significant public health impact.1 OA has been ranked as the 13th highest contributor to global disability in 2013 for 188 countries.2 The economic cost is considerable, estimated between 1% and 2.5% of the gross domestic product for Western countries.3

Risk factors for OA of the lower limbs include genetic inheritance, age, ethnicity, nutritional factors, female sex, local mechanical factors, obesity, and joint injury.4 OA of the hip and knee places the greatest burden on the population (physical, psychological, and socioeconomic) and often leads to significant pain and disability requiring surgical intervention.5 According to the OA definition used (self-reported, radiographic, symptomatic), the prevalence varies. Regardless of the definition used, the prevalence of knee OA ranged from 6.3% in Greece to 70.8% in Japan. However, the populations evaluated were very different in terms of age. OA of the knee tends to be more prevalent in women than in men independently of the OA definition used, but no sex differences were found in terms on OA of the hip. The hip joint has the lowest prevalence of OA.6

Total hip and knee replacement is an extremely successful surgical procedure and is cost effective as compared with the conservative management of OA.7 Thus, joint replacements are becoming more frequent for advanced osteoarthritis. The number of hip (HA) and knee (KA) arthroplasty procedures has increased rapidly since 2000 in most OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries. On average, the rate of hip replacement procedures increased by about 35% between 2000 and 2013, and the rate of knee replacement surgery nearly doubled.8 In the United States, by 2030, the demand for primary total HA is estimated to grow by 174% from their 2005 levels (572,000 annual procedures from 209,000), while the demand for primary total KAs is projected to grow by 673%, from 450,000 to 3.48 million annual procedures.9

In this study, we aimed to examine the variation in quality of life, function, stiffness, and pain in the patients’ first postsurgical year, and to identify (or characterize) the parameters influencing these elements. We have chosen to present the interim analysis during a 5-year follow-up process, in this case the first year which seemed to us to be crucial after KA and HA. We also tried to take advantage of a large, prospective cohort to better understand the determinants of clinical improvement and success following total joint arthroplasty, in osteoarthritic patients. interim analysis during a 5-year follow-up process

Method

This prospective study was conducted at the University Hospital of Liege in Belgium. All patients admitted to the institution who underwent KA or HA for knee or hip OA between December 2008 and January 2013 were considered eligible for enrolment in the study. The details of the recruitment were previously extensively described.10 The patients received and completed, without any external assistance, the first questionnaire the day before surgery. They completed the next questionnaire on the day before or on the day of hospital discharge. This provided information on their clinical course, hospital stay, and living situation after their hospital stay. Thereafter, the follow-up of postoperative outcomes continued by sending regular postal mails at different times up to 5 years of surgery. In this article, we presented the outcomes at different intervals: pre- and 3, 6, and 12 months’ post KA and HA.

We used a generic instrument for the assessment of quality of life, the Short Form 36 (SF-36) scale.11 The generic health measure SF-36 is a validated questionnaire assessing health-related quality of life (HRQoL). It is a self-administrated 36-item questionnaire comprising 8 health dimensions. Scoring ranges from 0 to 100 points, with higher scores representing better health. This tool also includes a separate variable assessing the perceived changes in overall health status compared to the status prevailing 1 year prior to the assessment. Pain, function, and stiffness were assessed using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC).12 The WOMAC includes 24 items covering 3 domains: pain, stiffness, and physical function, and captures the level of each domain with 5 response categories using an ordinal scale. Lower values in the traditional scoring method (ranging from 0 to 96) reflect a better health status. The utility was measured with 2 instruments developed by the EuroQol Group Association (EQ): the EuroQol Visual Analog Scale (EQ-VAS) and a generic tool assessing 5 dimensions (5D) of health: mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression (EQ-5D).13 Comorbidities were recorded and summarized using the Functional Comorbidity Index (FCI), which consists of a list of 18 diagnoses, each significantly associated with declining function. One point is assigned for the presence of each diagnosis, giving a global score between 0 and 18.14

Patient’s characteristics, presence of different comorbidities, pain, physical functioning, and HRQoL were analyzed using descriptive statistics. For normality and homogeneity of data, the tests of Shapiro-Wilk and Levene were used and then justified for nonparametric statistical analysis. Continuous variables are presented in the tables and figure as means and standard deviations (SDs) rather than medians with interquartile ranges (P25-P75) for reasons of visual relevance. Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. For the comparison between independent groups (HA and KA), in the case of continuous data (WOMAC scores, components variation over time and good outcome), the Mann-Whitney (2 samples) test was performed. Comparisons between baseline measures and 3-month to 1-year follow-ups were conducted using Friedman’s analysis of variance. The values of WOMAC (and subscales), EQ-5D and EQVAS at 3, 6, and 12 months were compared with those before surgery using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test.

Univariate and multivariate regression models were used to examine the relationship between changes in WOMAC total scores (dependent variables), preoperative patient characteristics, and occurrence of complications (independent variables). A significance level of 0.25 was used to include variables in the regression model. Initially, we considered the following as demographic and clinical variables: age, sex, level of education, incomes, duration of complaints, body mass index (BMI), Kellgren-Lawrence radiographic score (KL), FCI, background, type of prosthesis (total HA [THA] or hip resurfacing arthroplasty [HRA] in hip group and total KA [TKA] and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty [UKA] in knee group), mode of fixation (cemented/uncemented), weightbearing surface (HA), length of stay, place of exit, complications, and physical status before surgery (pain/stiffness/function). We started with the full model and we used a backward selection procedure to exclude variables (level of 0.05) that did not contribute significantly to the model. Results of the linear regression analyses were presented using regression coefficients (beta) and P values. R2 was calculated to assess the proportion of variance explained by the model.

After that, we looked for the predictors of a good outcome and compared the results. The good outcome is as an improvement in WOMAC total score greater than or equal to the minimal important difference (MID). The MID represented one-half of the standard deviation (SD) of the difference between pre–joint arthroplasty WOMAC total score and post–joint arthroplasty WOMAC total score.15,16 The proportion of patients that met criteria for good outcome was calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for HA and KA separately. The same demographic and clinical variables were considered in the logistic regression. A backward selection model was used to identify variables predictive of successful outcome.

Data were analyzed using STATISTICA, version 13, in a Windows environment. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for most analyses except the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Indeed, we adjusted the statistical significance level to P < 0.05/3 = 0.017.

Results

The final study cohort consisted of 626 subjects, 346 with hip OA (337 operated with THA and 9 with HRA [2.6%]) and 280 with knee OA (266 operated with TKA and 16 with UKA [5%]). The patient characteristics at baseline were extensively detailed in a previous publication.17 As reported, significant differences between subjects in need of a HA or of a KA were seen at the time of surgery in terms of age, duration of complaints, BMI, radiological status, comorbidities, surgical history trauma, and mean sick leave time. The characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1 . The hospital stay was longer after KA (8 vs. 7 days, P < 0.001) and a larger portion of patients were referred when leaving the hospital for a revalidation or convalescent structure (33.45% vs 23.12%, P = 0.004). The rate of early postoperative complications was similar in both groups. At the 1-year postsurgical follow-up, the complication rate was significantly higher in the KA group (22% vs. 7%), with the most frequent complication being the occurrence of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS). The most frequent complication in the HA group was dislocation and muscle/ligament problem (2% each) followed by periprosthetic fracture (1%). The persistence rate after 1 year was excellent with 90% of the patients in the KA group and 89% in the HA group who filled in the questionnaire at month 12. The reasons for withdrawal were related to the willingness to pursue the study, the length of the questionnaire, or because of personal problems. Only 8 patients in the KA group (2 for pain, 2 for CRPS, 2 for postoperative internal affection, 1 for ankylosis requiring mobilization under anesthesia and 1 for aseptic loosening) and 4 patients in the HA group (2 with luxation, 1 with periprosthetic fracture and 1 for pain), 3% and 1% respectively, decided to discontinue the study due to problems directly related to the surgical procedure.

Table 1.

Extended Characteristics of Patients at the Time of Hip or Knee Arthroplasty.

| Variables | Type of Prosthesis |

P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knee (n = 280; 44.73%) |

Hip (n = 346; 55.27%) |

||||||

| n | % | Mean ± SD | n | % | Mean ± SD | ||

| Age at the operation (years) | 66.74 ± 8.95 | 64.64 ± 10.85 | 0.03 | ||||

| Gender | 0.24 | ||||||

| Male | 128 | 45.71 | 142 | 41.04 | |||

| Female | 152 | 54.29 | 204 | 58.96 | |||

| Economically active | 50 | 17.86 | 72 | 20.81 | 0.35 | ||

| Mean sick leave time (days) | 182.87 ± 120.93 | 113.59 ± 91.90 | <0.001 | ||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.31 ± 4.71 | 27.42 ± 4.79 | <0.001 | ||||

| Surgical or traumatic background | 97 | 36.64 | 22 | 6.36 | <0.001 | ||

| Type of prosthesis | |||||||

| Unicompartmental | 14 | 5 | |||||

| Resurfacing | 9 | 2.60 | |||||

| Cemented fixation | 195 | 69.64 | 60 | 17.34 | <0.001 | ||

| Weightbearing surfaces | |||||||

| Ceramic/ceramic | 200 | 57.97 | |||||

| Metal/metal | 66 | 19.13 | |||||

| Metal/polyethylene | 27 | 7.83 | |||||

| Polyethylene/ceramic | 52 | 15.07 | |||||

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 8.62 ± 3.03 | 7.51 ± 7.02 | <0.001 | ||||

| Discharge status | 0.004 | ||||||

| Home | 185 | 66.55 | 266 | 76.88 | |||

| Nursing home—rehabilitation facility | 93 | 33.45 | 80 | 23.12 | |||

| Early postoperative complications | 38 | 13.57 | 38 | 10.98 | 0.27 | ||

| Skin problem | 7 | 2.5 | 6 | 1.73 | |||

| Internal affections | 19 | 6.79 | 20 | 5.78 | |||

| Muscle or ligament problem | 1 | 0.36 | |||||

| Venous thromboembolism | 2 | 0.71 | 3 | 0.87 | |||

| Fall | 9 | 3.21 | 3 | 0.87 | |||

| Luxation | 3 | 0.87 | |||||

| Fracture | 3 | 0.87 | |||||

| First year postoperative complications | 61 | 21.79 | 25 | 7.23 | 0.001 | ||

| Ankylosis requiring moblisation under anaesthesia | 9 | 3.21 | |||||

| Aseptic loosening | 2 | 0.71 | 1 | 0.29 | |||

| Complex regional pain syndrome | 34 | 12.14 | 1 | 0.29 | |||

| Periprosthetic fracture | 1 | 0.36 | 4 | 1.16 | |||

| Skin problem | 4 | 1.43 | 1 | 0.29 | |||

| Venous thromboembolism | 2 | 0.71 | 1 | 0.29 | |||

| Infection | 2 | 0.71 | 2 | 0.58 | |||

| Knee resurfacing | 3 | 1.07 | |||||

| Muscle or ligament problem | 4 | 1.43 | 7 | 2.02 | |||

| Luxation | 7 | 2.02 | |||||

| Heterotopic ossification | 1 | 0.29 | |||||

A statistically significant improvement was observed for the total WOMAC score and for the 3 WOMAC subscales from 3 months after surgery in both populations ( Table 2 ). A maximal improvement was observed during the first 3 months of the study, which continued, but at a lower rate until month 6, and then maintained or improved (total and pain) until the final follow-up (month 12). Regarding the SF-36, improvements were observed as soon as month 3 and continued up to month 12 in all physical and mental domains except for general perception of health (GH). This component remained broadly stable over time. As to the utility score, compared to baseline, significant changes in EQ-5D and EQ-VAS were reported from 3 months after surgery, followed by a period of increase until month 6 for EQ-5D, and a period stabilization until month 12 for EQ-VAS. There was no change in the FCI over time.

Table 2.

Summary of the Preoperative and Postoperative (3 Months to 1 Year) FCI, EQ, WOMAC, and SF-36 Scores.

| Variables | Type of Prosthesis |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knee |

P | Hip |

P | |||||||

| T0, Mean ± SD |

T3, Mean ± SD |

T6, Mean ± SD |

T12, Mean ± SD |

T0, Mean ± SD |

T3, Mean ± SD |

T6, Mean ± SD |

T12, Mean ± SD |

|||

| n = 280 | n = 253 | n = 247 | n = 245 | n = 346 | n = 310 | n = 305 | n = 302 | |||

| FCI | 2.62 ± 1.25 | 2.65 ± 1.28 | 0.063 | 2.41 ± 1.25 | 2.39 ± 1.24 | 0.098 | ||||

| EQ VAS | 65.09 ± 16.22 | 71.58 ± 15.42 | 72.88 ± 15.07 | 71.32 ± 18.41 | <0.001 | 62.51 ± 17.94 | 75.63 ± 15.49 | 75.90 ± 16.80 | 74.01 ± 17.94 | <0.001 |

| EQ 5D | 0.46 ± 0.23 | 0.66 ± 0.20 | 0.69 ± 0.19 | 0.67 ± 0.22 | <0.001 | 0.44 ± 0.23 | 0.71 ± 0.24 | 0.74 ± 0.25 | 0.71 ± 0.27 | <0.001 |

| WOMAC total (0-96) | 51.81 ± 16.89 | 33.08 ± 18.17 | 30.81 ± 18.43 | 29.53 ± 20.19 | <0.001 | 54.97 ± 16.83 | 25.19 ± 19.09 | 21.55 ± 19.99 | 18.80 ± 20.26 | <0.001 |

| Pain (0-20) | 10.97 ± 3.72 | 6.62 ± 3.98 | 5.99 ± 4.01 | 5.63 ± 4.37 | <0.001 | 11.28 ± 3.80 | 4.31 ± 4.22 | 3.77 ± 4.35 | 3.27 ± 4.20 | <0.001 |

| Stiffness (0-8) | 4.52 ± 1.88 | 3.36 ± 1.72 | 3.08 ± 1.69 | 2.93 ± 1.98 | <0.001 | 4.66 ± 1.82 | 2.53 ± 1.81 | 2.28 ± 1.98 | 1.85 ± 1.97 | <0.001 |

| Function (0-68) | 36.32 ± 12.77 | 23.09 ± 13.48 | 21.74 ± 13.80 | 20.96 ± 14.72 | <0.001 | 39.03 ± 12.51 | 18.36 ± 14.11 | 15.50 ± 14.49 | 13.68 ± 14.78 | <0.001 |

| SF-36 | ||||||||||

| Physical functioning (PF) | 33.96 ± 23.05 | 47.24 ± 24.43 | 51.19 ± 24.99 | 51.55 ± 27.42 | <0.001 | 32.34 ± 23.65 | 57.20 ± 26.70 | 61.56 ± 27.50 | 62.39 ± 28.56 | <0.001 |

| Physical role functioning (RP) | 29.38 ± 37.04 | 31.57 ± 37.77 | 43.93 ± 41.18 | 48.57 ± 42.38 | <0.001 | 25.43 ± 35.20 | 42.23 ± 41.88 | 57.98 ± 42.70 | 60.15 ± 42.89 | <0.001 |

| Emotional role functioning (RE) | 48.57 ± 43.15 | 48.02 ± 43.12 | 56.68 ± 44.16 | 59.86 ± 42.67 | <0.001 | 49.61 ± 43.24 | 58.58 ± 43.01 | 66.23 ± 41.93 | 66.78 ± 42.33 | <0.001 |

| Vitality (VT) | 48.07 ± 19.16 | 49.38 ± 19.17 | 53.60 ± 18.83 | 52.51 ± 20.98 | <0.001 | 46.13 ± 20.35 | 54.17 ± 20.47 | 55.20 ± 21.72 | 55.10 ± 20.23 | <0.001 |

| Mental health (MH) | 61.24 ± 21.24 | 63.89 ± 21.03 | 64.70 ± 21.48 | 65.21 ± 22.66 | <0.01 | 61.12 ± 21.73 | 66.49 ± 21.07 | 67.71 ± 22.45 | 66.07 ± 22.29 | <0.001 |

| Social role functioning (SF) | 68.67 ± 24.98 | 70.17 ± 23.15 | 72.27 ± 22.71 | 73.01 ± 24.65 | 0.01 | 64.60 ± 25.56 | 73.83 ± 23.18 | 76.32 ± 23.82 | 74.92 ± 25.31 | <0.001 |

| Bodily pain (BP) | 33.90 ± 17;72 | 51.41 ± 21.59 | 56.09 ± 22.24 | 54.51 ± 23.98 | <0.001 | 32.14 ± 20.30 | 62.18 ± 23.59 | 66.43 ± 25.84 | 66.01 ± 26.68 | <0.001 |

| General health perceptions (GH) | 61.93 ± 18.65 | 62.94 ± 18.55 | 63.12 ± 19.43 | 61.10 ± 19.75 | 0.12 | 60.69 ± 19.42 | 63.67 ± 20.35 | 63.19 ± 21.25 | 62.39 ± 21.82 | 0.11 |

| Health change | 40.54 ± 18.69 | 59.46 ± 24.03 | 63.66 ± 24.96 | 62.45 ± 24.34 | <0.001 | 35.26 ± 21.18 | 70.15± 23.51 | 71.55 ± 27.18 | 68.73 ± 27.25 | <0.001 |

FCI = Functional Comorbidity Index; EQ = EuroQol Group Association; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (can have a total score of 0 [best] to 96 [worst]). Pain subscale: 0 (best) to 20 (worst); stiffness: 0 (best) to 8 (worst); function: 0 (best) to 68 (worst); SF-36 = Short Form 36 scale (the components can have a total score of 0 [worst] to 100 [best]); SD = standard deviation

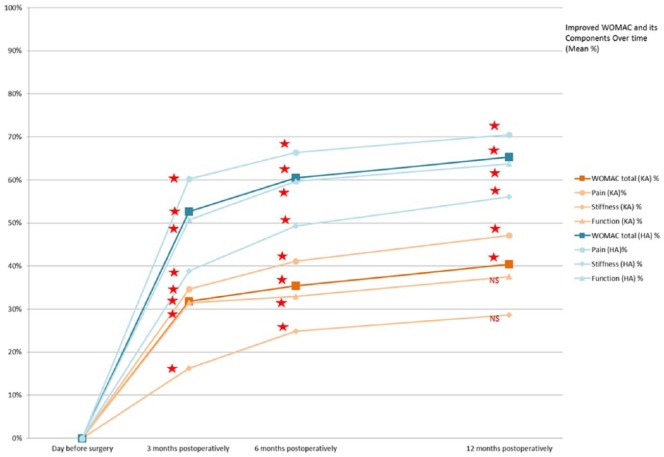

The improvement in the total WOMAC score and subscales was significantly greater for HA patients than for KA patients at all time points (3, 6, 12 months: P < 0.001) ( Fig. 1 ). The function and stiffness component improved up to 12 months for the hip and reached a plateau at 6 months for the knee. Thus, in the KA group, there was no difference between the improvement in function and stiffness observed at 6 months and that observed at 1 year. However, there was a difference in the improvement in function and stiffness between the third postoperative month and the 12th postoperative month.

Figure 1.

WOMAC and components variation over time (% mean). WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. No standard deviation (SD) for reasons of clarity (but summarized in Table annexed). *Significant difference from previous follow-up (Wilcoxon test). NS = no significant difference from previous follow-up (Wilcoxon test).

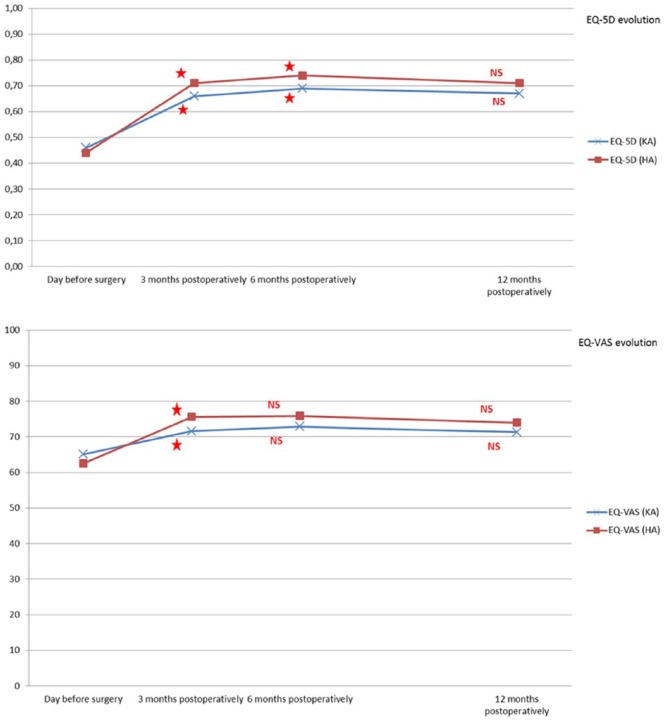

In both populations (ie, HA and KA groups), the maximal improvement in EQ (5D and VAS) was observed during the first 3 months of the trial, with a subsequent moderate increase up to month 6, and then a small decrease (not significant) between month 6 and month 12 for EQ-5D and stabilization up to months 12 for EQ-VAS ( Fig. 2 ).

Figure 2.

EQ-5D and EQ-VAS evolution over time (mean). EQ-VAS = EuroQol Visual Analog Scale; EQ-5D = EuroQol 5 dimensions of health. No standard deviation (SD) for reasons of clarity (but summarized in Table annexed). *Significant difference from previous follow-up (Wilcoxon test). NS = no significant difference from previous follow-up (Wilcoxon test)

In the final multivariate linear regression analyses ( Table 3 ), a low number of comorbidities and the absence of postoperative complications were the common determinants of a beneficial outcome, both for the hip and knee groups after 12 months. Similar results were observed for the pain and function components. In patients with KA, the lack of surgical or traumatic background and the preoperative function were also identified as positive factors for a better functional outcome after 12 months. Patients who had poorer preoperative function were more likely to experience greater improvement. Conversely, a shorter duration of hospital stay was a positive predictive factor. In patients with HA, returning home was also identified as a positive factor for a better functional outcome after 12 months. These parameters explain 8% (HA group) and 11% (KA group) of the variance of the WOMAC total score.

Table 3.

Prediction of a Higher Variation in WOMAC Total Score 1 Year After HA and KA on Multivariable Analysis (Final Model).

| Predictors in the KA model | Postoperative WOMAC Total Score (r2 = 0.11) |

|

|---|---|---|

| B (95% CI) | P | |

| FCI | −3.74 (−7.64 to −0.07) | 0.049 |

| Surgical or traumatic background | −10.85 (−20.52 to −1.17) | 0.03 |

| Length of stay | −2.54 (−4.07 to −1.01) | <0.01 |

| 1-year postoperative complications | −13.73 (−24.63 to −2.84) | 0.01 |

| Preoperative physical function | 0.54 (0.17 to 0.91) | <0.01 |

| Constant | 4.98 (−25.77 to 35.73) | 0.75 |

| Predictors in the HA model | Postoperative WOMAC Total Score (r2 = 0.08) |

|

| B (95% CI) | P | |

| FCI | −6.08 (−9.41 to −2.74) | <0.001 |

| Place of discharge following hospital stay | −14.74 (−24.53 to −4.96) | <0.01 |

| 1-year postoperative complications | −17.41 (–33.29 to −1.53) | 0.01 |

| Constant | 46.72 (26.42 to 67.02) | 0.96 |

WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; HA = hip arthroplasty; KA = knee arthroplasty; FCI = Functional Comorbidity Index.

The mean ± SD changes from presurgery to postsurgery in hip/knee WOMAC total score were 35.62 ± 22.10 and 22.90 ± 20.10, respectively. The calculated MID were 11.05-point improvement for HA, and 10.05 for KA. A total of 87.09% of HA (n = 263; 95% CI 83.31%-90.87%) and 73.06% of KA (n = 179; 95% CI 67.50%-78.62%) met the MID criterion for a good outcome. Using backward regression, the predictors of good HA/KA outcome using this criterion in the final model included the preoperative function, the number of comorbidities, the occurrence of early postoperative complications (only HA) and the length of hospital stay (only KA). In the HA group, the probability of achieving a good outcome was greater for those with worse preoperative function (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.03-1.10, P < 0.001), less comorbidity (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.41-0.74, P < 0.001) and the absence of early postoperative complications (OR 3.24, 95% CI 1.29-8.13, P < 0.05). In the KA group, worse preoperative function (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.04-1.11, P < 0.001), less comorbidity (OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.45-0.79, P < 0.001), and a shorter hospital stay (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.72-0.94, P < 0.05) were significant predictors of good outcome.

Discussion

The present study evaluated and compared prospective quality of life after KA and HA, as well as the effects of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics on specific outcomes (WOMAC total scores). We chose to use high methodological quality patient-reported outcome measures developed for patients undergoing hip or knee replacement surgery: condition-specific and generic instruments. We selected the WOMAC score, a hip and knee specific score, well-validated and widely used for the assessment of pain, function, and stiffness of osteoarthritis in the lower limbs.18 Regarding generic measures and utility, we choose the SF-36 and EQ-5D. The SF-36 is worth considering, as this is the most comprehensively generic measure tested in the arthroplasty population.19 EQ-5D is 1 of the most commonly used generic preference-based measures in economic evaluation and the most widely used metric to derive utilities in osteoarthritis.20,21 Generally, our results were in line with international guidelines showing that joint replacement is cost effective for the management of end-stage knee OA when all previous modalities have failed and a significant loss in quality of life is present.22,23 The recommendations for hip OA were similar to those for the management of knee OA.24

Our study showed that in advanced OA of the lower limbs, knee or hip arthroplasty improves quality of life, function, and health utilities and reduces pain and stiffness. Treatment appeared to be extremely quickly effective (after 3 months). This positive result was maintained at 12 months. A previous systematic review by Ethgen et al.25 in 2004 demonstrated the same early HRQoL benefits. The time improvement profile of the different outcomes is similar, namely a rapid increase that reached its maximum between 3 and 6 months before a long-lasting improvement. Another study considered the same parameters in a cohort of 222 osteoarthritis patients undergoing total hip or knee replacement and showed improvements in pain and function at 2 years similar to those observed at 6 months.26 Whereas several studies showed that direct interventions on the cartilage (e.g., cartilage grafts or stem cells transplantation) are extremely promising strategies to improve of repair cartilage defect,27,28 one limitation of these approaches remains the time needed for the patient to perceive a significant improvement in symptoms and quality of life similar to what is reported to occur in a few weeks after total joint arthroplasty.29,30 Total joint arthroplasty remains also the most appropriate intervention when a large proportion of the cartilage surface/volume is missing or severely compromised, a situation where benefits of cartilage repair remains to be extensively assessed in clinical trials.31

We found significant differences between patients who had a hip or knee arthroplasty with regard to the mean change in the WOMAC scores and subscales. Thus, HA patients displayed greater improvements in pain, stiffness, and function as compared with KA patients at 3, 6, and 12 months’ follow-up. Several studies, using the same tools, have reported similar results with inferior outcomes for KA as compared with for HA. Bachmeier et al.32 reported greater improvement in the SF-36 and WOMAC scores for patients who had HA than for KA. Patients were followed up over a period of 1 year at 3-month intervals.32 Similar results on the SF-36 and the WOMAC were found by March et al.33 with a similar follow-up. In a 1-year prospective study, Bourne et al.34 showed that WOMAC change scores were better for patients undergoing primary THA than primary TKA in terms of pain relief, joint stiffness, and function. Using the SF-36 only, other studies reported that improvement after HA was notably greater than after KA,35-38 and that outcomes for KA and HA were similar.39,40 A recent study showed that WOMAC scores improved significantly after 1 year for both HA and KA, but WOMAC total and function scores were significantly better in the TKA group at all time points (3, 6, 12 months). In this study, KA patients experienced a significantly shorter hospital stay, and this could help explain this difference in the results.41

In our study, 2 elements were observed as common predictors of a favorable 1-year WOMAC total evolution. These included the absence of complications and a low number of comorbidities. Greater comorbidity was recently shown in 2 systematic reviews to significantly determine lower changes in pain and functional status after TKA (12 out of 23 studies) and THA (7 out of 8).42,43 The absence of complications in the first year is significantly related to a better outcome in the 2 groups. It will be interesting in a later study to reassess a longer-term situation and to compare the profile of patients with or without postoperative complications during the first year and following. Indeed, there is an abundance of evidence in the literature to suggest higher rates of short- to medium-term complications in obese patients, particularly in the morbidly obese patients. These complications may also be related to the greater number of comorbidities in obese patients. The 2 elements are therefore closely interlinked.44,45

Among the other preoperative parameters, in the KA group, the surgical or traumatic background of the joint and the preoperative function affected the evolution of WOMAC scores. This is consistent with the argument that patients with worse presentation (poorer preoperative HRQoL) are more likely to experience greater improvement.25 Regarding the background of the joint, previous knee surgery and posttraumatic OA were significant predictors of dissatisfaction after 1 year. Postfracture OA has been associated with inferior outcomes and elevated complication rates; however, previous meniscectomy has not.46-50 As for complications, it will be interesting to reassess the long-term situation in a later study and to analyze the profile of patients with or without a previous knee surgery or posttraumatic OA. In the HA group, among the clinical determinants, only the number of comorbidities affected the evolution of WOMAC scores. The preoperative level of function was not predictive of the outcome. This is in agreement with a recent study, but contradicts the previously held belief that patients with worse function before HA do not function as well as those with less preoperative disability.51 Among the intraoperative and postoperative parameters, a short length of hospital stay (KA) and the return home (HA) are also determinants of better outcomes. Negative correlations between quality of recovery and length of hospital stay were found for both kinds of arthroplasty, but quality of recovery put different emphases on the WOMAC scores.52

In our study, home discharge is a positive determinant of a better outcome only after HA. This is inconsistent with 2 other studies. In these, there was no difference in health status at 12 months between the group that received home-based rehabilitation and the group that had inpatient rehabilitation. However, these studies have certain specificities that distinguish these characteristics. In the first, the population was much more restricted (118 patients) and the second was a randomized controlled trial. Therefore, the choice of the place of discharge was not taken into account for the functional state of the patient.53,54

Under the “good outcome” definition, more than 70% of patients with of hip or knee replacement in our study (73% and 87%, respectively) experienced an important improvement in their hip/knee status greater than or equal to MID. These proportions of individuals with a good outcome, as we defined it, was similar than has been reported previously using the MID definition, except one (but follow-up period of 6 months).55-57 Three variables in each group predicted those who experienced a successful outcome. Thus, patients with worse prearthroplasty WOMAC function, less comorbidity, shorter length of stay (KA group only) and less immediate complications (HA group only) were more likely to benefit from arthroplasty outcome. Worse OA-related disability prior to surgery and comorbidity were preoperative variables also found in other studies. These findings suggested that patients with the worst preoperative function have the most to gain from HA and KA. They may not have better absolute outcomes than those with better preoperative HRQoL scores, but they may see the biggest gain. This probably explained why the preoperative function variable was only found in the KA group in the final multivariate linear regression analyses.

Among the other key factors associated with the development of degenerative joint disease and influencing selection for total joint arthroplasty, age and obesity are not found to be an obstacle for effective surgery and had similar outcomes on improvement of WOMAC scores at 12 months.58 In the case of BMI, there would be no impact on the outcomes but rather on the risk of complications in the first 12 months after joint arthroplasty. However, 2 recent reviews of the literature with a follow-up from 3 months to 2 years has shown that higher BMI could have an influence on poor outcomes after THA (6 out of 10 studies) and TKA (4 studies out of 13 studies).42,43 Similarly, there were no age-related differences in joint pain, function, or quality-of-life measures preoperatively or 6 months postoperatively after THA and TKA.59 However, results were conflicting regarding TKA. A study showed that increasing age was associated with worse 1-year postoperative functional outcomes, but the population was different (large majority of women and bilateral procedure in 60% of patients).60 Another study went in the opposite direction with young patients whose outcome scores did not match those attained by older patients. Again, the population was different with a majority of patients younger than 55 years, whereas we only had a few patients in this age range.61 In 2 recent reviews of preoperative determinants of outcomes, 3 to 24 months’ follow-up of THA/TKA, the majority of studies did not identify an influence of age (10 out of 15 studies in the knee group and 7 out of 11 studies in the hip group).42,43

In our study, the improvement in WOMAC scores was not associated with the preoperative radiographic severity. In this area, there is no consensus and the results have always varied according to the studies. In a recent study, the decrease in pain and improvement in function 1 year after surgery was positively associated with the preoperative radiographic severity of OA, but only in the THA group. However, the radiological profile of the patients was not the same with most grade 4 (severe) OA, and the evaluation tool was not the WOMAC, but the HOOS/KOOS (Hip disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score/Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score).62 In the previously mentioned review, a lower radiographic OA severity was associated with poor outcomes in 3 out of 4 studies after HA.42 In the review of the knee, this parameter was not evaluated in the various studies.43 There was, however, a relationship between age and radiographic severity, but the effects of radiographic disease severity on patient-reported scores were not significantly different.61

In both groups, we did not observe any impact on the evolution of WOMAC scores according to the type of prosthesis (TKA or UKA, THA or HRA), but the number of patients in the UKA and HRA groups was low. Nevertheless, this is consistent with different studies. With regard to the knee, a study in 2013 had not shown any significant difference over the first 6 months following surgery.63 Similarly, for the hip, in 1 and 2 years postsurgery, the improvements in WOMAC scores were similar after THA and HRA.64

Finally, the adjustment quality of the model measured by the determination coefficient (R2 adjusted) was quite low, standing at 10%. There are, therefore, other explanatory variables not evaluated in this study.

The strengths of the study are its prospective design, the large cohort, the high rates of follow-up return, the large number of investigated preoperative and postoperative (i.e., immediate and mid-terms complications, length of hospital stay and place of discharge following hospital stay) variables and the use of 2 health care professionals who were not part of the surgical management team. These individuals recruited patients and followed them up at each assessment. We used highly validated tools for this indication. It could be argued that the Oxford hip or knee questionnaires could have been used. Indeed, according to a 2001 study, the 12 items in the Oxford questionnaires appeared to be superior for patients who have had knee or hip arthroplasty.65,66 However, the French versions were validated in 2009 for the hip and in 2011 for the knee, after the beginning of the recruitment of patients (2008).67,68 We, therefore, complied with the recommendations of the editors of the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American to use the WOMAC to report the longer term follow-up status of patients managed with THA and applied it for the knee also.18,69

However, we acknowledge that this study presents certain limitations such as the involvement of only 1 center; therefore, multicenter research is needed for generalization of the results. Additionally, 10% of KA patients and 11% of HA patients were lost to follow-up, and 3% and 1%, respectively, to arthroplasty complications. There could also still be a discreet selection bias common to prospective cohort studies. Other potential determinants of improvement following total knee replacement were not assessed: patient expectations and the presence of other troublesome hips/knees.57,70 Finally, the clinical relevance of “improvement” in scores is unknown. Do we have to wait for patients to have a more preoperative function that is more altered in order to hope for a result that is considered a success? Or do we operate patients with fewer preoperative limitations that will reach a threshold considered a success faster?16 Some authors tried to define appropriateness criteria for arthroplasty, but there is still no consensus.71-74 This study could provide some elements for further investigation.

One year is a relatively short-term follow-up but we will continue to monitor these patients up to 5 years. We would like to see if the improvement continues during the course, placing the results in perspective with those from other studies. Finally, we would like to evaluate whether new determinants of clinical evolution are highlighted. Concerning knee prostheses, 2 studies indicated a pattern of HRQoL improvements for up to 1 year, after which scores began to decline but remained superior to preoperative levels.75,76 In the longer term (15 years), pain and satisfaction scores in this population were good, even in patients who underwent revision surgery.77 In the THA group, mean clinical outcome scores were found to be relatively constant from 1 to 6 years after surgery.78

Conclusion

In conclusion, the most important finding of this study is the demonstration of a significant improvement of all parameters reflecting quality of life and the health utility as soon as 3 months after knee or hip replacement. This study adds substantially to the currently available evidence. In addition, the improvement in outcomes following hip joint surgery is significantly greater than that following knee surgery.

A few preoperative parameters positively affected the evolution of WOMAC scores. In the KA group, it was the low number of comorbidities, the absence of surgical or traumatic background of the joint, and a poorer preoperative function. In the HA group, only the number of comorbidities affected the WOMAC evolution. Among the intraoperative and postoperative parameters, the absence of a postoperative complications (both groups), a short length of hospital stay (KA), and the return home (HA) were also determinants of better outcomes. Therefore, we suggest that according to this study, patients should not be denied surgery based on demographic determinants such as age, sex, or BMI. We identify also factors that are predictors of a better outcome following HA and KA: disability prior to surgery and the number of comorbidities.

Further studies need to explore the long-term evolution, through the WOMAC and other parameters, and the profile of patients with complications.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments and Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the local medical ethical committee (University Hospital Liège (707)—Approval number: B70720084766).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study.

Trial Registration: Not applicable.

References

- 1. Neogi T, Zhang Y. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39(1):1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):743-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hiligsmann M, Cooper C, Arden N, Boers M, Branco JC, Luisa Brandi M, et al. Health economics in the field of osteoarthritis: an expert’s consensus paper from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43(3):303-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hunter DJ. Osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(6):801-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Litwic A, Edwards MH, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Epidemiology and burden of osteoarthritis. Br Med Bull. 2013;105:185-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pereira D, Peleteiro B, Araujo J, Branco J, Santos RA, Ramos E. The effect of osteoarthritis definition on prevalence and incidence estimates: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(11):1270-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nwachukwu BU, Bozic KJ, Schairer WW, Bernstein JL, Jevsevar DS, Marx RG, et al. Current status of cost utility analyses in total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(5):1815-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. OECD. Hip and knee replacement. Health at a glance 2015. Paris, France: OECD; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Neuprez A, Neuprez AH, Kurth W, Gillet P, Bruyere O, Reginster JY. Profile of osteoarthritic patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty, a step toward a definition of the “need for surgery”. Aging Clin Exp Res. Epub 2017 May 30. doi: 10.1007/s40520-017-0780-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SK. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scale: a user’s manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kopec JA, Willison KD. A comparative review of four preference-weighted measures of health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(4):317-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Groll DL, To T, Bombardier C, Wright JG. The development of a comorbidity index with physical function as the outcome. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(6):595-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Devji T, Guyatt GH, Lytvyn L, Brignardello-Petersen R, Foroutan F, Sadeghirad B, et al. Application of minimal important differences in degenerative knee disease outcomes: a systematic review and case study to inform BMJ Rapid Recommendations. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e015587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Losina E, Katz JN. Total joint replacement outcomes in patients with concomitant comorbidities: a glass half empty or half full? Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(5):1157-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neuprez A, Neuprez AH, Kurth W, Gillet P, Bruyère O, Reginster JY. Profile of osteoarthritic patients undergoing total hip and knee arthroplasty. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harris K, Dawson J, Gibbons E, Lim CR, Beard DJ, Fitzpatrick R, et al. Systematic review of measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures used in patients undergoing hip and knee arthroplasty. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2016;7:101-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alviar MJ, Olver J, Brand C, Tropea J, Hale T, Pirpiris M, et al. Do patient-reported outcome measures in hip and knee arthroplasty rehabilitation have robust measurement attributes? A systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43(7):572-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin FJ, Longworth L, Pickard AS. Evaluation of content on EQ-5D as compared to disease-specific utility measures. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(4):853-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ruchlin HS, Insinga RP. A review of health-utility data for osteoarthritis: implications for clinical trial-based evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(11):925-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bruyere O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP, Branco J, Luisa Brandi M, Guillemin F, et al. An algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis in Europe and internationally: a report from a task force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(3):253-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. NCGC (UK). Osteoarthritis: care and management in adults. London, England: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(4):465-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ethgen O, Bruyere O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(5):963-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fortin PR, Penrod JR, Clarke AE, St-Pierre Y, Joseph L, Belisle P, et al. Timing of total joint replacement affects clinical outcomes among patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(12):3327-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berebichez-Fridman R, Gomez-Garcia R, Granados-Montiel J, Berebichez-Fastlicht E, Olivos-Meza A, Granados J, et al. The Holy Grail of orthopedic surgery: mesenchymal stem cells-their current uses and potential applications. Stem Cells Int. 2017;2017:2638305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wyles CC, Houdek MT, Behfar A, Sierra RJ. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for osteoarthritis: current perspectives. Stem Cells Cloning. 2015;8:117-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vega A, Martin-Ferrero MA, Del Canto F, Alberca M, Garcia V, Munar A, et al. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: a randomized controlled trial. Transplantation. 2015;99(8):1681-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Orozco L, Munar A, Soler R, Alberca M, Soler F, Huguet M, et al. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with autologous mesenchymal stem cells: two-year follow-up results. Transplantation. 2014;97(11):e66-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tuan RS, Chen AF, Klatt BA. Cartilage regeneration. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(5):303-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bachmeier CJ, March LM, Cross MJ, Lapsley HM, Tribe KL, Courtenay BG, et al. A comparison of outcomes in osteoarthritis patients undergoing total hip and knee replacement surgery. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9(2):137-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. March L, Cross M, Tribe K, Lapsley H, Courtenay B, Brooks P. Cost of joint replacement surgery for osteoarthritis: the patients’ perspective. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(5):1006-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bourne RB, Chesworth B, Davis A, Mahomed N, Charron K. Comparing patient outcomes after THA and TKA: is there a difference? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(2):542-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kiebzak GM, Campbell M, Mauerhan DR. The SF-36 general health status survey documents the burden of osteoarthritis and the benefits of total joint arthroplasty: but why should we use it? Am J Managed Care. 2002;8(5):463-74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kiebzak GM, Vain PA, Gregory AM, Mokris JG, Mauerhan DR. SF-36 general health status survey to determine patient satisfaction at short-term follow-up after total hip and knee arthroplasty. J South Orthop Assoc. 1997;6(3):169-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Albert TJ, Balderston RA, Eng K. Relationship of total hip arthroplasty outcomes to other orthopaedic procedures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997(344):88-93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McGuigan FX, Hozack WJ, Moriarty L, Eng K, Rothman RH. Predicting quality-of-life outcomes following total joint arthroplasty. Limitations of the SF-36 Health Status Questionnaire. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(6):742-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ritter MA, Albohm MJ, Keating EM, Faris PM, Meding JB. Comparative outcomes of total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(6):737-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baumann C, Rat AC, Osnowycz G, Mainard D, Cuny C, Guillemin F. Satisfaction with care after total hip or knee replacement predicts self-perceived health status after surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dailiana ZH, Papakostidou I, Varitimidis S, Liaropoulos L, Zintzaras E, Karachalios T, et al. Patient-reported quality of life after primary major joint arthroplasty: a prospective comparison of hip and knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lungu E, Maftoon S, Vendittoli PA, Desmeules F. A systematic review of preoperative determinants of patient-reported pain and physical function up to 2 years following primary unilateral total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102:397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lungu E, Vendittoli PA, Desmeules F. Preoperative determinants of patient-reported pain and physical function levels following total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Open Orthop J. 2016;10:213-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dowsey MM, Liew D, Stoney JD, Choong PF. The impact of obesity on weight change and outcomes at 12 months in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. Med J Aust. 2010;193(1):17-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kulkarni K, Karssiens T, Kumar V, Pandit H. Obesity and osteoarthritis. Maturitas. 2016;89:22-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Scott CE, Oliver WM, MacDonald D, Wade FA, Moran M, Breusch SJ. Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee arthroplasty in patients under 55 years of age. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(12):1625-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Scott CE, Davidson E, MacDonald DJ, White TO, Keating JF. Total knee arthroplasty following tibial plateau fracture: a matched cohort study. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(4):532-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Weiss NG, Parvizi J, Hanssen AD, Trousdale RT, Lewallen DG. Total knee arthroplasty in post-traumatic arthrosis of the knee. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(3 Suppl 1):23-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Issa K, Naziri Q, Johnson AJ, Pivec R, Bonutti PM, Mont MA. TKA results are not compromised by previous arthroscopic procedures. J Knee Surg. 2012;25(2):161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kester BS, Minhas SV, Vigdorchik JM, Schwarzkopf R. Total knee arthroplasty for posttraumatic osteoarthritis: is it time for a new classification? J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(8):1649-53.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Alzahrani MM, Smith K, Tanzer D, Tanzer M. Primary total hip arthroplasty: equivalent outcomes in low and high functioning patients. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24(11):814-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Johansson Stark A, Charalambous A, Istomina N, Salantera S, Sigurdardottir AK, Sourtzi P, et al. The quality of recovery on discharge from hospital, a comparison between patients undergoing hip and knee replacement—a European study. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(17-18):2489-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mahomed NN, Davis AM, Hawker G, Badley E, Davey JR, Syed KA, et al. Inpatient compared with home-based rehabilitation following primary unilateral total hip or knee replacement: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(8):1673-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tribe KL, Lapsley HM, Cross MJ, Courtenay BG, Brooks PM, March LM. Selection of patients for inpatient rehabilitation or direct home discharge following total joint replacement surgery: a comparison of health status and out-of-pocket expenditure of patients undergoing hip and knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. Chronic Illn. 2005;1(4):289-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Judge A, Cooper C, Williams S, Dreinhoefer K, Dieppe P. Patient-reported outcomes one year after primary hip replacement in a European Collaborative Cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(4):480-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vina ER, Hannon MJ, Kwoh CK. Improvement following total knee replacement surgery: exploring preoperative symptoms and change in preoperative symptoms. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(5):547-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hawker GA, Badley EM, Borkhoff CM, Croxford R, Davis AM, Dunn S, et al. Which patients are most likely to benefit from total joint arthroplasty? Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(5):1243-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Changulani M, Kalairajah Y, Peel T, Field RE. The relationship between obesity and the age at which hip and knee replacement is undertaken. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(3):360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jones CA, Voaklander DC, Johnston DW, Suarez-Almazor ME. The effect of age on pain, function, and quality of life after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(3):454-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chang CB, Yoo JH, Koh IJ, Kang YG, Seong SC, Kim TK. Key factors in determining surgical timing of total knee arthroplasty in osteoarthritic patients: age, radiographic severity, and symptomatic severity. J Orthop Traumatol. 2010;11(1):21-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Haynes J, Sassoon A, Nam D, Schultz L, Keeney J. Younger patients have less severe radiographic disease and lower reported outcome scores than older patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2017;24:663-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tilbury C, Holtslag MJ, Tordoir RL, Leichtenberg CS, Verdegaal SH, Kroon HM, et al Outcome of total hip arthroplasty, but not of total knee arthroplasty, is related to the preoperative radiographic severity of osteoarthritis. A prospective cohort study of 573 patients. Acta Orthop. 2016;87(1):67-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sweeney K, Grubisic M, Marra CA, Kendall R, Li LC, Lynd LD. Comparison of HRQL between unicompartmental knee arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty for the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(9 Suppl):187-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Alberta Hip Improvement Project, MacKenzie JR, O’Connor GJ, Marshall DA, Faris PD, Dort LC, et al. Functional outcomes for 2 years comparing hip resurfacing and total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(5):750-7.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dunbar MJ, Robertsson O, Ryd L, Lidgren L. Appropriate questionnaires for knee arthroplasty. Results of a survey of 3600 patients from The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(3):339-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ostendorf M, van Stel HF, Buskens E, Schrijvers AJ, Marting LN, Verbout AJ, et al. Patient-reported outcome in total hip replacement. A comparison of five instruments of health status. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(6):801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Delaunay C, Epinette JA, Dawson J, Murray D, Jolles BM. Cross-cultural adaptations of the Oxford-12 HIP score to the French speaking population. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(2):89-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jenny JY, Diesinger Y. Validation of a French version of the Oxford knee questionnaire. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2011;97(3):267-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Poss R, Clark CR, Heckman JD. A concise format for reporting the longer-term follow-up status of patients managed with total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(12):1779-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Mahomed NN, Liang MH, Cook EF, Daltroy LH, Fortin PR, Fossel AH, et al. The importance of patient expectations in predicting functional outcomes after total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(6):1273-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Riddle DL, Jiranek WA, Hayes CW. Use of a validated algorithm to judge the appropriateness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: a multicenter longitudinal cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(8):2134-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Riddle DL, Perera RA, Jiranek WA, Dumenci L. Using surgical appropriateness criteria to examine outcomes of total knee arthroplasty in a United States sample. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67(3):349-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Escobar A, Quintana JM, Arostegui I, Azkarate J, Guenaga JI, Arenaza JC, et al. Development of explicit criteria for total knee replacement. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19(1):57-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Katz JN, Winter AR, Hawker G. Measures of the appropriateness of elective orthopaedic joint and spine procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(4):e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gandhi R, Dhotar H, Razak F, Tso P, Davey JR, Mahomed NN. Predicting the longer term outcomes of total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2010;17(1):15-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nilsdotter AK, Toksvig-Larsen S, Roos EM. A 5 year prospective study of patient-relevant outcomes after total knee replacement. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(5):601-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Loughead JM, Malhan K, Mitchell SY, Pinder IM, McCaskie AW, Deehan DJ, et al. Outcome following knee arthroplasty beyond 15 years. Knee. 2008;15(2):85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Gandhi R, Dhotar H, Davey JR, Mahomed NN. Predicting the longer-term outcomes of total hip replacement. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(12):2573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]