Abstract

Objectives:

Increased mortality has been documented in older homeless veterans. This retrospective study examined mortality and cause of death in a cohort of young and middle-aged homeless veterans.

Methods:

We examined US Department of Veterans Affairs records on homelessness and health care for 2000-2003 and identified 23 898 homeless living veterans and 65 198 non-homeless living veterans aged 30-54. We used National Death Index records to determine survival status. We compared survival rates and causes of death for the 2 groups during a 10-year follow-up period.

Results:

A greater percentage of homeless veterans (3905/23 898, 16.3%) than non-homeless veterans (4143/65 198, 6.1%) died during the follow-up period, with a hazard ratio for risk of death of 2.9. The mean age at death (52.3 years) for homeless veterans was approximately 1 year younger than that of non-homeless veterans (53.2 years). Most deaths among homeless veterans (3431/3905, 87.9%) and non-homeless veterans (3725/4143, 89.9%) were attributed to 7 cause-of-death categories in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (cardiovascular system; neoplasm; external cause; digestive system; respiratory system; infectious disease; and endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases). Death by violence was rare but was associated with a significantly higher risk among homeless veterans than among non-homeless veterans (suicide hazard ratio = 2.7; homicide hazard ratio = 7.6).

Conclusions:

Younger and middle-aged homeless veterans had higher mortality rates than those of their non-homeless veteran peers. Our results indicate that homelessness substantially increases mortality risk in veterans throughout the adult age range. Health assessment would be valuable for assessing the mortality risk among homeless veterans regardless of age.

Keywords: homelessness, mortality, survival, cause of death

Homeless populations are at substantial risk for early death as a result of chronic disorders such as hepatitis and cardiovascular disease.1-4 These health problems are in part attributable to the increased exposure of the homeless population to environmental toxins and communicable diseases, chronic stress associated with low socioeconomic status, malnutrition, psychiatric and substance use disorders, and barriers to access to health care. Veterans compose a substantial minority of the US homeless population. Although efforts to reduce veteran homelessness have been somewhat successful, in 2016, veterans composed 11% of the homeless adult US population.5 To date, however, few studies have explored early mortality among homeless veterans.

Retrospective studies of mortality among homeless veterans with mental illness showed rates that are higher than those of the general population and those of non-homeless veterans with mental illness.6 Homelessness contributes to years of life lost above and beyond the impact of serious mental illness.7 Analyses of age differences at time of death from suicide show that homeless veterans who died by suicide were significantly younger than were veterans without a history of homelessness who died by suicide.8 In a 1-year follow-up of veterans receiving US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care in north Texas in 2010, homeless veterans had a 32.3% increase in all-cause mortality compared with non-homeless veterans.9 These results were maintained even after controlling for age, race, sex, serious mental illness, substance use, and disease comorbidity.

In the most recently reported study,10 VA homeless program and health care records were examined in samples of 4775 homeless veterans and 20 071 non-homeless veterans aged ≥55. The survival rate and causes of death of the 2 groups during an 11-year follow-up period showed that substantially more homeless veterans (34.9%) than non-homeless veterans (18.2%) died. Homeless veterans were approximately 2.5 years younger at the time of death than non-homeless veterans, and the lowest survival rate (58%) was among homeless veterans aged ≥60.10

In summary, the few studies of homeless veterans suggest early mortality. These estimates may be biased to some degree, however, because most study samples consisted of veterans who were either identified in records of medical care or enrolled in medical or psychiatric treatment programs. Only the study of older homeless veterans10 included a study sample of veterans selected solely on the basis of their homeless status. In this retrospective cohort study, we examined mortality patterns in a large sample of young to middle-aged homeless veterans identified solely by their entry into national VA homeless programs. We examined differences between homeless and non-homeless veterans in all-cause and specific-cause mortality, including death by violent means.

Methods

The VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center, the VA Corporate Data Warehouse, and the Epidemiology Program of the VA Office of Public Health provided data for the study. The VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center provided administrative data for the registry of all veterans aged 18-54 who were admitted into VA homeless programs during calendar years 2000-2003. Veterans in these programs qualify for VA health care, but a substantial percentage use non-VA resources for some or all of their health care.11,12 The VA Corporate Data Warehouse provided administrative records containing data on age, date of birth, and sex for veterans who received medical care from the VA during calendar years 2000-2003. These records were culled to selected veterans of either sex who were aged 18-54 at the time of their first contact for medical care during 2000-2003. Veterans with a subsequent history of intervention in VA homeless programs, as indicated in VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center data for calendar years 2000-2011, were not included in the sample. This study was approved by the Tampa VA research committee and the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board. A waiver of the consent process was approved for this use of archived data.

An examination of the age distributions of the 2 samples revealed that relatively few veterans in the homeless sample (2.1%) were aged 18-29. To match more closely the age distributions of the homeless and control samples on a group basis, we reduced the age range for the study samples to 30-54. The final homeless sample consisted of 23 898 veterans, and the final non-homeless sample consisted of 65 198 veterans.

Homeless veterans are infrequent and inconsistent users of VA health care services. Because of limited data on the use of VA health care services by the homeless sample and community-based care for both samples, no other variables were used to match the groups. Only sex and age were available as covariates in statistical analyses.

The Epidemiology Program of the VA Office of Public Health provided mortality data from the National Death Index maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for 2000-2011. We matched records for homeless and non-homeless veterans against the National Death Index files to determine survival status, date of death, and cause of death. For mortality analyses, we calculated time to death as the date of death minus the entry date into the VA homeless program for homeless veterans and the date of first contact for medical care service for the period 2000-2003 for non-homeless veterans. The follow-up period therefore ranged from 8 to 11 years, depending on the date of entry or first contact. We used International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10)13 codes provided in the National Death Index file to determine categories of cause of death (eg, cardiovascular disease). We also determined the specific causes of death for death by suicide and homicide and for other external causes of death. We captured data on death by suicide by using the ICD-10 codes intentional self-harm (X60-X84) and “late effects” (ie, sequelae) of intentional self-harm (Y87.0). We determined death by homicide by using ICD-10 codes X92-Y09. We evaluated descriptive statistics for demographic characteristics of homeless and non-homeless veterans and univariate statistics for mortality data comparing deceased and surviving veterans.

We used survival table analysis to estimate and plot cumulative survival function curves. A survival curve gives the probability that a person will survive longer than a specified time or period. We calculated hazard functions for homeless and non-homeless veterans using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. We adjusted all regression analyses for covariates of sex and age. In each regression analysis, we examined the assumption of proportional hazards over time for sex through log (–log) plots of the class survival function and found them to be tenable. We also examined variance inflation factor values for the covariates for indications of multicollinearity. We conducted all analyses using SPSS version 22.14

Results

All-Cause Deaths

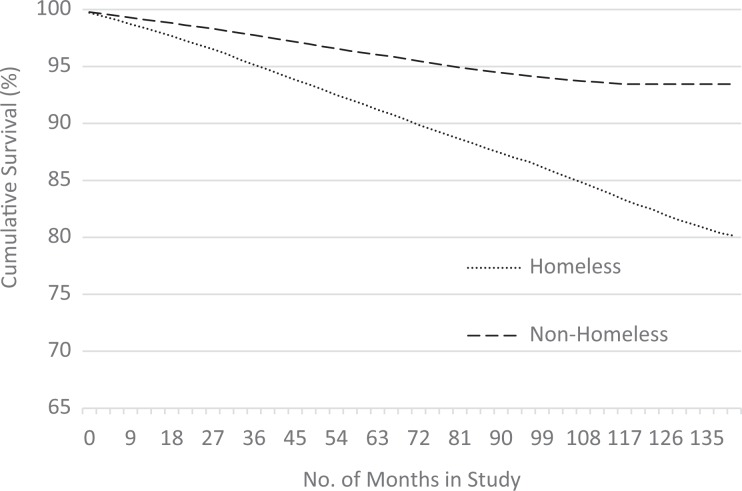

The mean follow-up period for the study was approximately 10 years (119.7 months). A small difference in mean (standard deviation [SD]) age at study entry between non-homeless veterans (45.1 [7.1]) and homeless veterans (45.1 [5.7]) was not significant (t = 0.60, df = 53-139, P = .55). We also found a small but not significant difference in the percentage of females in non-homeless veterans (3.4%) and homeless veterans (3.6%) (χ2 1 = 1.1, P = .27). During the follow-up period, 3905 of 23 898 (16.3%) homeless veterans died of all causes; a significantly smaller proportion (n = 4143/65 198, 6.1%) of non-homeless veterans died of all causes (χ2 1 = 2122.2, P < .001). Covariate-adjusted regression analysis showed an increased risk of death for homeless veterans, with a hazard ratio of 2.9 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.8-3.1; P < .001). Homeless veterans were slightly but significantly younger at the time of death (mean [SD] age = 52.3 [5.9]) than were non-homeless veterans (mean [SD] age = 53.2 [5.7]) (t 7981 = 6.75, P < .001) and survived significantly fewer months in the follow-up period (mean [SD] length = 108.4 [27.7] months vs 115.7 [22.8] months; t 36 569 = 36.95, P < .001). We also found a substantive decline in survival for homeless veterans during the follow-up period (Figure). Log-rank tests showed that the overall difference in survival was significant (χ2 1 = 2177.0, P < .001).

Figure.

Survival curves for homeless and non-homeless veterans aged 30-54, identified in 2000-2003 and followed through 2011, United States. Data sources: data provided by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Northeast Program Evaluation Center, the VA Corporate Data Warehouse, and the Epidemiology Program of the VA Office of Public Health.

Categories of Cause of Death

Seven ICD-10 cause-of-death categories comprised most (88.9%) deaths overall, including 87.9% (3431/3905) of deaths among homeless veterans and 89.9% (3725/4143) of deaths among non-homeless veterans: cardiovascular system; neoplasm; external cause; digestive system; respiratory system; infectious disease; and endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases (Table). In examining the percentage of deaths among all veterans, the covariate-adjusted regression analysis showed an increased rate of death for homeless veterans for all of these categories of causes of death, with hazard ratios ranging from 2.0 to 5.2. The highest hazard ratio (5.2) was for the category of external causes of death; the rate of death attributed to external causes among homeless veterans was more than 5 times the rate among non-homeless veterans.

Table.

Causes of death among homeless and non-homeless veterans aged 30-54, identified in 2000-2003 and followed through 2011, United Statesa

| ICD-10 Cause of Death | Homeless Veterans (n = 23 898) | Non-Homeless Veterans (n = 65 198) | Hazard Ratio for Homeless Status (95% CI) | P Valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Deaths (% of Homeless Veterans) | % of Homeless Veteran Deaths | No. of Deaths (% of Non- Homeless Veterans) | % of Non- Homeless Veteran Deaths | |||

| All causes | 3905 (16.3) | 100.0 | 4143 (6.4) | 100.0 | 2.9 (2.8-3.1) | <.001 |

| Most common categories of cause of death | ||||||

| Cardiovascular system | 969 (4.1) | 24.8 | 1192 (1.8) | 28.8 | 2.8 (2.6-3.1) | <.001 |

| Neoplasm | 619 (2.6) | 15.9 | 1120 (1.7) | 27.0 | 2.0 (1.8-2.2) | <.001 |

| External cause | 934 (3.9) | 23.9 | 557 (0.9) | 13.4 | 5.2 (4.7-5.8) | <.001 |

| Digestive disorders | 357 (1.5) | 9.1 | 334 (0.5) | 8.1 | 3.7 (3.2-4.3) | <.001 |

| Respiratory disorders | 200 (0.8) | 5.1 | 211 (0.3) | 5.1 | 3.5 (2.9-4.3) | <.001 |

| Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases | 119 (0.5) | 3.0 | 165 (0.3) | 4.0 | 2.5 (2.0-3.2) | <.001 |

| Infectious and parasitic diseases | 233 (1.0) | 6.0 | 146 (0.2) | 3.5 | 5.1 (4.2-6.4) | <.001 |

| Most common subcategories of external causes of death | ||||||

| Suicide | 130 (0.5) | 3.3 | 148 (0.2) | 3.6 | 2.7 (2.2-3.5) | <.001 |

| Homicide | 75 (0.3) | 1.9 | 32 (0.0) | 0.8 | 7.6 (5.0-11.5) | <.001 |

| Exposure to prescribed or illegal drugs (accidental overdose) | 373 (1.6) | 9.6 | 134 (0.2) | 3.2 | 8.7 (7.1-10.6) | <.001 |

| Transportation accidents (vehicle and pedestrian) | 127 (0.5) | 3.3 | 121 (0.2) | 2.9 | 3.3 (2.5-4.2) | <.001 |

| Non-vehicle accidents (eg, falls, drowning) | 159 (0.7) | 4.1 | 75 (0.1) | 1.8 | 6.8 (5.2-9.1) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision.13

aData sources: US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Northeast Program Evaluation Center, the VA Corporate Data Warehouse, and the Epidemiology Program of the VA Office of Public Health.

bTest of significance for hazard ratio.

Subcategories of External Causes of Death

Further examination of external causes of death showed that 91% of deaths among homeless veterans and 90% of deaths among non-homeless veterans were attributed to 1 of 5 causes of death: suicide, homicide, exposure to prescribed or illegal drugs (accidental overdose), transportation accidents (vehicle and pedestrian), and non-vehicle accidents (eg, falls, drowning). The rate of veteran deaths in the homeless sample was higher than the rate of veteran deaths in the non-homeless sample for each cause of death, with hazard ratios ranging from 2.7 (suicide) to 8.7 (accidental overdose) (Table).

Discussion

Frequency of all-cause death during the follow-up period was more than twice as high for homeless veterans (16.3%) as for non-homeless veterans (6.4); the associated hazard ratio was 2.9. National mortality statistics estimate that 6.8% of men aged 25-54 die during a time period equivalent to the study follow-up period (10 years). Mortality among homeless veterans was not only higher than among non-homeless veterans, but it was also approximately twice as high as expected based on national mortality estimates. In combination with results of previous work on homeless veterans, these results lend further support to the hypothesis of excess mortality among homeless veterans and provide estimates of mortality risk for this population.

Almost all deaths that occurred during the follow-up period were in 7 cause-of-death categories, and the 3 most common causes of death for both groups (cardiovascular diseases, neoplasms, and external causes) were consistent with the 3 most common causes of death for men in this age group nationally. Notably, death due to external causes was associated with a significant and meaningful proportional increase in homeless veteran mortality compared with non-homeless veteran mortality. Nearly one-quarter of deaths among homeless veterans were due to external causes, including drug overdose, suicide, homicide, and accidents. Frequency of death by suicide was rare in both groups (0.74% for homeless veterans vs 0.28% for non-homeless veterans) but was associated with a significantly higher hazard ratio for homeless people. National mortality estimates for men in equivalent age ranges show that 0.29% died by suicide during a 10-year period.15 Death by homicide was also rare, occurring in 0.31% of homeless veterans and 0.04% of non-homeless veterans. Again, this cause of death occurred at a significantly higher rate in the homeless population compared with the non-homeless population. Equivalent estimates of male homicides in specific age ranges are difficult to determine reliably, but the national estimate of deaths for all groups by homicide during a period equivalent to the follow-up period in this study was 0.06%.16 In summary, homeless veterans die by violent causes at a significantly higher rate than non-homeless veterans or males in general. The pattern of results indicates that this finding is attributable to homelessness above and beyond veteran status.

The rate of death due to drug overdose was significantly higher among homeless veterans than among non-homeless veterans, which was expected given the high rate of drug use in all homeless populations. The rate of death resulting from non-vehicle accidents was also substantially higher for homeless veterans than for non-homeless veterans. Among veterans dying of external causes, approximately 30% died as a result of non-vehicle accidents. One possible explanation for the mortality due to these accidents may be the documented high rate of alcohol and drug use in homeless veterans and the fact that intoxication is associated with death due to accident.17,18

This study makes an important contribution to the literature by extending the findings of a previous study on homeless veterans10: we showed that increased mortality is characteristic not only of older homeless veterans (aged ≥55) but also of those in younger age groups. In both age groups, being homeless substantially increased mortality compared with being non-homeless. In addition, death by suicide occurred at a higher rate in the homeless populations in both studies. The most substantive difference in the results of the 2 studies was the role of external causes as a cause-of-death category in the younger homeless veterans group.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study was that homeless veterans were not selected from larger samples of veterans composed solely of those with mental health or substance use disorders. Because 35% of homeless veterans do not have mental health or substance use disorders, this study examined mortality in a sample more likely to reflect the actual composition of the homeless veteran population. This study was limited by the fact that data on the homeless veteran sample were not more complete. Thus, we could not conduct analyses that could be adjusted by factors such as diagnosed medical and psychiatric comorbidities, substance use disorders, and use of VA and especially community-based health care services. Although a previous study with a limited sample9 found a substantial increase in all-cause mortality even after controlling for some of these factors, more accurate estimates in homeless veterans will require more comprehensive adjustments.

Conclusions

Our study and previous studies show that homeless veterans are at increased risk for early death, regardless of age at the time of homelessness. Future studies should use longitudinal approaches to explore not only risk factors but also the impact of long-term housing interventions and health care access on homeless veteran longevity. In the interim, however, data are sufficient to support the consideration of focused treatment for homeless veterans within the framework of VA health care services. The VA Homeless Patient Aligned Care Team program19 would be a valuable vehicle for this approach, providing facilitated access to care for homeless veterans located in VA facility catchment areas.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans, Department of Veterans Affairs. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US government.

References

- 1. Barrow SM, Herman DB, Córdova P, Struening EL. Mortality among homeless shelter residents in New York City. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(4):529–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hibbs JR, Benner L, Klugman L, et al. Mortality in a cohort of homeless adults in Philadelphia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(5):304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hwang SW, Lebow JM, Bierer MF, O’Connell JJ, Orav EJ, Brennan TA. Risk factors for death in homeless adults in Boston. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(13):1454–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morrison DS. Homelessness as an independent risk factor for mortality: results from a retrospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(3):877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development. The 2016 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress: Part 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness in the U.S . Washington, DC: US Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2016. https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2016-AHAR-Part-2-Section-5.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kasprow WJ, Rosenheck R. Mortality among homeless and nonhomeless mentally ill veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188(3):141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Birgenheir DG, Lai Z, Kilbourne AM. Datapoints: trends in mortality among homeless VA patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(7):608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bossarte RM, Piegari R, Hill L, Kane V. Age and suicide among veterans with a history of homelessness. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(7):713–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. LePage JP, Bradshaw LD, Cipher DJ, Crawford AM, Hoosyhar D. The effects of homelessness on veterans’ health care service use: an evaluation of independence from comorbidities. Public Health. 2014;128(11):985–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schinka JA, Bossarte RM, Curtiss G, Lapcevic WA, Casey RJ. Increased mortality among older veterans admitted to VA homelessness programs. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(4):465–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O’Toole TP, Conde-Martel A, Gibbon JL, Hanusa BH, Fine MJ. Health care of homeless veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(11):929–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Petrovich JC, Pollio DE, North CS. Characteristics and service use of homeless veterans and nonveterans residing in a low-demand emergency shelter. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(6):751–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14. IBM Corp. SPSS Version 22.0 for Windows. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Suicide rates for females and males by race and ethnicity: United States, 1999 and 2014. April 2016 https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/suicide/rates_1999_2014.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2018.

- 16. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65(4):1–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miller TR, Spicer RS. Hospital-admitted injury attributable to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(1):104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith GS, Branas CC, Miller TR. Fatal nontraffic injuries involving alcohol: a meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(6):659–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O’Toole TP, Johnson EE, Aiello R, Kane V, Pape L. Tailoring care to vulnerable populations by incorporating social determinants of health: the Veterans Health Administration’s “homeless patient aligned care team” program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]