Abstract

Kaempferia parviflora (Krachaidum) is a medicinal plant in the family Zingiberaceae. Its rhizome has been used as folk medicine for many centuries. A number of pharmacological studies of Krachaidum had claimed benefits for various ailments. Therefore, this study aimed to systematically search and summarize the clinical evidences of Krachaidum in all identified indications. Of 683 records identified, 7 studies were included. From current clinical trials, Krachaidum showed positive benefits but remained inconclusive since small studies were included. Even though results found that Krachaidum significantly increased hand grip strength and enhanced sexual erotic stimuli, these were based on only 2 studies and 1 study, respectively. With regard to harmful effects, we found no adverse events reported even when Krachaidum 1.35 g/day was used. Therefore, future studies of Krachaidum are needed with regards to both safety and efficacy outcomes.

Keywords: Kaempferia parviflora, systematic review, complementary and alternative medicine

Kaempferia parviflora or Krachaidum (in Thai), also known as “Thai ginseng,” is a medicinal plant in the family Zingiberaceae. It is found in tropical areas such as Malaysia, Sumatra, Borneo Island, and Thailand. Its rhizome has been long used as folk medicine for many centuries.1 Among the Hmong hill tribe, Krachaidum is widely believed to reduce perceived effort, improve physical work capacity, and prolong hill trekking. A number of pharmacological studies of Krachaidum have shown the following properties: antiallergenic,2,3 anti-inflammatory,4 antimutagenic,5 antidepressive,6 anticholinesterase,7 antimicrobial,8,9 anticancer,10–12 anti–-peptic ulcer,13 cardioprotective,14,15 antiobesity activity,16 and aphrodisiac.17–20

Phytochemicals of Krachaidum contain 2 major constituents: 5,7-dimethoxyflavone and 5,7,4′-trimethoxyflavone.21 In an in vitro study, methoxyflavone was examined for its inhibitory activities against nitric oxide production. Compound 5 (5-hydroxy-3,7,30,40-tetramethoxyflavone) exhibited the highest activity, followed by compounds 4 (5-hydroxy-7,40-dimethoxyflavone) and 3 (5-hydroxy-3,7,40-trimethoxyflavone), whereas other compounds possessed moderate or weak activity.4 In addition, more than 20 chemically identifiable constituents have been reported to have potent pharmacological effects.22 For example, flavonoids contained in Krachaidum rhizome extract was reported to possess antioxidant activity, neuroprotective effects, and cognition-enhancing effects.21 Methoxyflavone substances in Krachaidum showed an inhibitory effect of phosphodiesterase types 5 and 6, which enhanced sexual performance.20 For antimicrobial activity, 5,7,4′-trimethoxyflavone and 5,7,3′,4′-tetramethoxyflavone exhibited antiplasmodial activity against Plasmodium falciparum, and 3,5,7,4′-tetramethoxyflavone showed antifungal activity against Candida albicans.8 For cholinesterase inhibitory effect, Krachaidum showed the potential inhibitors toward acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase, which may be of great interest to be considered as a treatment agent for Alzheimer’s disease.7 Considering adverse events of Krachaidum used, an animal histopathological study of visceral organs revealed no remarkable lesions related to the toxicity of Krachaidum extract.23

According to the anecdotal evidence of safety and efficacy, Krachaidum has been selected in Thailand as 1 of the 5 champion herbal products that have been widely used and have generated income to the country.22,24 However, even though widely used for a long time and having shown benefits, clinical studies in human are still limited. Therefore, this study aims to systematically search and summarize the evidence in favor Krachaidum from existing clinical trials in all identified indications.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in line with the Cochrane Collaboration framework guidelines,25 and the study follows the PRISMA Statement.26

Search Strategies

The following databases were used to search for original research articles from inception to January 2016: PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials, CINAHL, AMED, WHO Registry, www.clinicaltrial.gov, Health Science Journals in Thailand, Thai Library Integrated System, Thai Thesis Database, Thai Index Medicus, and Thai Medical Index. Strategic search terms included “Kaempferia parviflora,” “Black ginger,” “Krachaidum” (a Thai word for Kaempferia parviflora), or other synonym names. References of articles derived for full-text review were scanned to identify potential studies not indexed in the above databases.

Study Selection

Studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) conducted in humans, (2) evaluated clinical effects of Krachaidum, and (3) had a control group. Two authors (SS and PW) independently scanned all the titles and abstracts to determine whether the studies assessed the clinical effects of Krachaidum. Full-text articles of the potential studies were subsequently assessed by SS and PW. When disagreements and uncertainties regarding eligibility occurred, they were resolved by consensus discussions.

Data Extraction

Two authors (PW and PR) independently extracted data using a data extraction form and confirmed by a third author (SS) in line with the CONSORT statement for reporting herbal medicinal interventions.27 The data extracted and reported included the following: study design, number of participants, age of participants, herbal compress ingredients, characteristics of the intervention, and outcome measurement. Outcomes of interest depended on indication of Krachaidum, for example, physical or exercise performance, erectile response.

Quality Assessment

Studies included in this review were assessed for methodological quality by SS and PW using the Cochrane risk of bias tool25 and Jadad score.28 The Cochrane risk of bias evaluates bias in intervention studies based on a number of criteria, including the following: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. Studies in which baseline characteristics were different among study groups or not tested for their difference were considered as high risk for the domain of “other risk of bias.” Each study was classified as having low risk (low risk of bias for all key domains), high risk (high risk of bias for one or more key domains), or unclear risk (unclear risk of bias for one or more key domains). Disagreements between the reviewers were settled through discussion and consensus.

Statistical Analysis

Data from all studies were pooled in a meta-analysis to determine the overall effect size with 95% confidence interval. Pooled effects were calculated and stratified according to indications of Krachaidum and its comparators. The outcome variables were compared between intervention and comparator arms by calculating the overall mean differences, which could be (1) standardized mean difference for outcomes that were measured by different scales across studies; or (2) weighted mean difference for outcomes that were measured on the same scale.25

Statistical heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the χ2 test and I2. Thresholds of I2 were interpreted in accordance with the magnitude and direction of effects and strength of evidence of heterogeneity (ie, P value) as follows: might not be important (0% to 40%), moderate heterogeneity (30% to 60%), substantial heterogeneity (50% to 90%), and considerable heterogeneity (75% to 100%).25 The DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model29 was employed for all analyses. Meta-analyses were conducted using STATA version 14 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

Study Selection

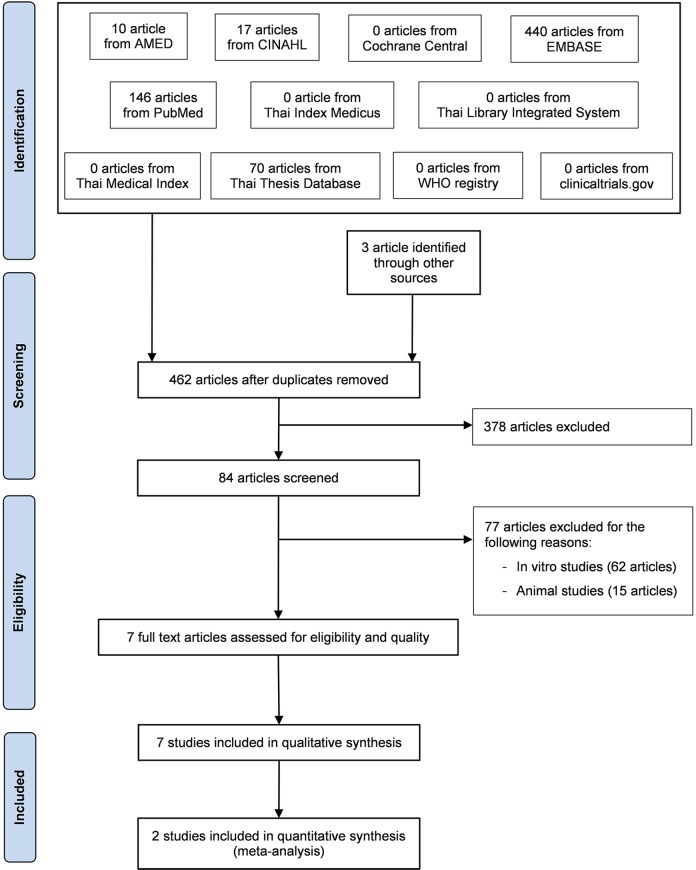

A total of 683 records were identified through database searching (n = 680) and other sources (n = 3). A total of 462 records remained after duplicates were removed. Of the remaining 462 records, 378 were deemed ineligible based on title and abstract. Of the 84 articles qualified for a full-text review, 77 full-text articles were excluded because they did not meet the study eligibility criteria. The flow chart in Figure 1 presents the results describing exclusions at different stages during the review process. Seven studies were included in this systematic review.30–36

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of selected articles.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

The general characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1. Of the 7 included randomized controlled trials, 6 studies were from Thailand,30–35 and 1 study was done in Japan.36 Five studies were conducted in healthy volunteers,30–32,34,36 and one each studied in male soccer players33 and patients with diagnosed osteoarthritis.35 Among the included studies that reported patients’ age and gender, the average age ranged from 16 to 66 years, and all patients were men in 5 studies,30,31,33,34,36 except the study of Chalee,35 which consisted of 26.5% of men, while one study did not report gender of participants.32 Most studies used Krachaidum as powder in capsule and compared with placebo, except the study of Chalee,35 which used Krachaidum as cream and compared with analgesic creams. Duration of study varied from 90 minutes31,36 to 4 weeks,35 8 weeks,30,32,34 and 12 weeks.33 Considering outcomes of interest, 4 studies focused on physical or exercise performance,30–33 while one each focused on erectile response,34 pain indicators,35 and energy expenditure.36 All studies reported that they used standardized extract of Krachaidum. Three studies reported that they used thin-layer chromatography fingerprint30 or high-performance liquid chromatography,31,36 while 4 studies reported that a standardized extract of Krachaidum was prepared by the Center for Research and Development of Herbal Health Product, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Khon Kaen University.32–35

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Included Studies.

| Study, Country | Design (Jadad Scale) | Participants’ Characteristics | N | Mean Age (in Years) | Men (%) | Intervention Group With Dose | Comparison Group | Standardization of Krachaidum | Extraction Method | Outcomes | Duration of Study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Method | |||||||||||

| Physical or exercise performance | ||||||||||||

| Deema (2007),30 Thailand | RCT (Jadad = 3) | Healthy males age 18-35 years | 30 | 22.0 | 100 | KP 1.35 g in capsules with endurance training (n = 11) or without endurance training (n = 5) | Placebo capsules with endurance training (n = 10) or without endurance training (n = 4) | Quantifying its content according the standard procedure | TLC fingerprint | Ethanol extract | Maximum power output (watt), Time to finish work max test (min), Heart rate (BPM), Lactate threshold (watt) | 8 weeks |

| Wasuntarawat (2010),31 Thailand | RCT (Jadad = 4) | Healthy males | 19 | 20.0 | 100 | KP 1.35 g in capsules | Placebo | Validated by quantifying its content of 5,7-dimethoxyflavone and 5,7,40-trimethoxyflavone | HPLC | NR | Maximum power output (watt), Mean power output (watt), Time to exhaustion (min), Rating of perceived exertion, Percentage fatigue (%), Heart rate (BPM) | 90 minutes |

| Wattanathorn (2012),32 Thailand | RCT (Jadad = 4) | Healthy elderly were older than 60 years | 45 | 62.8 | NR | KP 25 mg in capsules (n = 15) and 90 mg (n = 15) | Placebo (n = 15) | Assured by strict in-process controls during manufacturing and complete analytical control of the resulting dry extract | KKU | 95% ethanol extract | Hand grip strength test (kg), 30-Second chair stand test (seconds), 6-Minute walk test (meter), Tandem test (seconds) | 8 weeks |

| Promthep (2015),33 Thailand | RCT (Jadad = 4) | Males soccer players age 15-18 years | 60 | 16.0 | 100 | KP 180 mg in capsules (n = 30) | Placebo (n = 30) | Assured by strict in-process controls during manufacturing and complete analytical control of the resulting dry extract | KKU | 95% ethanol extract | Grip strength test (kg/wt), Back-and-leg test (kg/wt), Sit-and-reach test (cm), 40-Yard technical test (seconds), 50-Metre sprint test (seconds), Cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2 max) test (mL/kg/min) | 12 weeks |

| Erectile response | ||||||||||||

| Wannanon (2012),34 Thailand | RCT (Jadad = 5) | Healthy elderly volunteers | 45 | 66.0 | 100 | KP 25 mg in capsules (n = 15) and 90 mg (n = 15) | Placebo (n = 15) | Assured by strict in-process controls during manufacturing and complete analytical control of the resulting dry extract | KKU | 95% ethanol extract | Latency time (min), Penile circumference and length (cm), Serum hormones concentrations (testosterone (ng/mL), FSH (IU/L), LH (IU/L) | 8 weeks |

| Pain indicators | ||||||||||||

| Chalee (2010),35 Thailand | RCT (Jadad = 5) | Patients were older than 50 years with diagnosed OA | 70 | 61.0 | 26.5 | KP 7%w/w creams applied 1 sachet (2 g) 3 time a day (n = 35) | Analgesic creams (n = 35) | KP 7%w/w | KKU | 95% ethanol extract | Pain score, Circumference of knee joint (cm), Range of motion of knee joint (ROM), Modified WOMAC score | 4 weeks |

| Energy expenditure | ||||||||||||

| Matsushita (2015),36 Japan | RCT, crossover trial (Jadad = 1) | Healthy males aged 21-29 years | 20 | 24.1 | 100 | KP 100 mg/day in capsules | Placebo | Revealed that the KP extract contained 3,5,7,4′-tetramethoxyflavone (2.16%), 5,7-dimethoxyflavone (4.07%), and 3,5,7,3′,4′-pentamethoxyflavone (4.25%) | HPLC | 60% ethanol extract | Energy expenditure change (kJ/day) | 90 minutes |

Abbreviations: RCT, randomized controlled trial; KP, Kaempferia parviflora; N, number of participants; TLC, thin layer chromatography; BPM, beats per minute; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; NR, not reported; KKU, a standardized extract of Kaempferia parviflora prepared by the Center for Research and Development of Herbal Health Product, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Khon Kaen University; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index; OA, osteoarthritis.

Quality Assessment

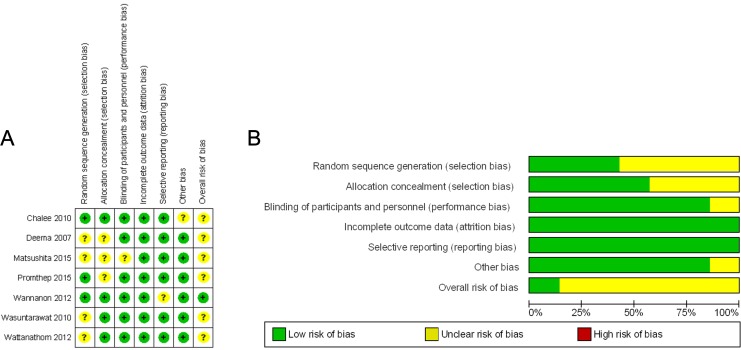

The methodological quality of the 7 randomized controlled trials included in the systematic review was high as shown by Jadad scale score of 3 (scale score range of 0-5), except the study of Matsushita et al,36 which had a Jadad scale score of 1 (Table 1). In addition, based on the risk of bias of key domains, overall risk of bias within the studies in most studies yielded unclear risk of bias (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias: (A) Risk of bias in each study; (B) Summary risk of bias of included studies.

Clinical Effects of Krachaidum on Physical or Exercise Performance

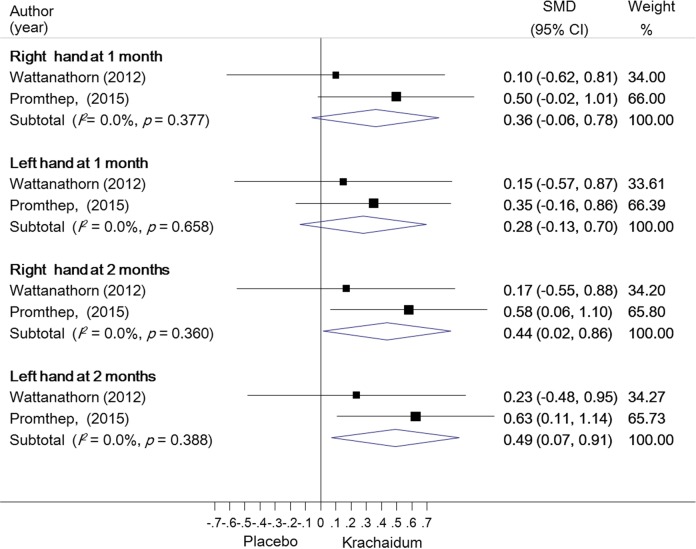

To determine the effects of Krachaidum on physical or exercise performance, many tests were used, including maximum power output, mean power output, time to exhaustion, rating of perceived exertion, percentage fatigue, heart rate, lactate threshold, hand grip strength, 6-minute walk test, and so on (Table 2). The main findings from 2 studies30,31 indicated that Krachaidum showed no acute improvement in either repeated sprint performance or endurance exercise. However, 2 studies32,33 provided data of hand grip strength test, which determined the upper-body muscle strength by using a digital dynamometer. We pooled such data based on this outcome and found that they were combinable without heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P > .05). We found that the Krachaidum group significantly increased hand grip strength of both right-hand (standardized mean difference = 0.44, 95% confidence interval = 0.02-0.86, P = .038) and left-hand sides (standardized mean difference = 0.49, 95% confidence interval = 0.07-0.91, P = .048) at 2 months compared with the placebo group (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Clinical Effects of Krachaidum Classified by Outcomes.

| Outcomes, Study | Sample Subgroup | Interventions | Time or Methods of Measurement | Kaempferia parviflora | Control | Summary | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||||||

| Physical or exercise performance | |||||||||||

| Maximum power output (watt) | |||||||||||

| Deema, 2007 | Endurance training groups | KP 1.35 g/day vs placebo | Baseline | 203.50 | 3.30 | 214.20 | 2.40 | Significantly increased at weeks 4 and 8 in the KP group and week 8 in the placebo group (difference from baseline) | |||

| 4 weeks | 233.70 | 2.90 | 232.10 | 1.60 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 245.00 | 3.20 | 247.00 | 2.90 | |||||||

| No endurance training groups | Baseline | 184.10 | 2.80 | 200.80 | 4.90 | No significant effects | |||||

| 4 weeks | 190.50 | 2.10 | 197.40 | 5.30 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 192.00 | 2.00 | 198.20 | 5.30 | |||||||

| Wasuntarawat, 2010 | Anaerobic exercise (exhaustive sprint) | KP 1.35 g/day vs placebo | Wingate 1 | 545.00 | 95.00 | 554.00 | 114.00 | Maximum power output declined (P < .05) across Wingate tests 1, 2, and 3 but there were no differences (P > .05) between KP and placebo | |||

| Wingate 2 | 499.00 | 99.00 | 495.00 | 109.00 | |||||||

| Wingate 3 | 454.00 | 116.00 | 473.00 | 96.00 | |||||||

| Mean power output (watt) | |||||||||||

| Wasuntarawat, 2010 | Anaerobic exercise (exhaustive sprint) | KP 1.35 g/day vs placebo | Wingate 1 | 417.00 | 65.00 | 416.00 | 65.00 | Mean power output declined (P < .05) across Wingate tests 1, 2, and 3 but there were no differences (P > .05) between KP and placebo | |||

| Wingate 2 | 369.00 | 59.00 | 369.00 | 58.00 | |||||||

| Wingate 3 | 323.00 | 61.00 | 334.00 | 57.00 | |||||||

| Time to finish work max test (minutes) | |||||||||||

| Deema, 2007 | Endurance training groups | KP 1.35 g/day vs placebo | Baseline | 8.20 | 0.10 | 8.50 | 0.10 | Significantly increased at weeks 4 and 8 in the KP group and week 8 in the placebo group (difference from baseline) | |||

| 4 weeks | 9.20 | 0.10 | 9.40 | 0.10 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 9.70 | 0.10 | 9.90 | 0.1 0 | |||||||

| No endurance training groups | Baseline | 7.20 | 0.10 | 7.90 | 0.20 | No significant effects | |||||

| 4 weeks | 7.50 | 0.10 | 7.80 | 0.20 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 7.50 | 0.10 | 7.80 | 0.10 | |||||||

| Time to exhaustion (minutes) | |||||||||||

| Wasuntarawat, 2010 | Anaerobic exercise (exhaustive sprint) | KP 1.35 g/day vs placebo | 28.30 | 12.50 | 27.60 | 11.50 | Acute ingestion of KP did not improve time to exhaustion | ||||

| Rating of perceived exertion | |||||||||||

| Wasuntarawat, 2010 | Anaerobic exercise (exhaustive sprint) | KP 1.35 g/day vs placebo | 10 min | 14.00 | 2.00 | 14.00 | 2.00 | Ratings of perceived exertion at 10 and 20 minutes and immediately after exhaustion were also not different between placebo and KP. Time to exhaustion was rated between 17 (“very hard”) and 19 (“extremely hard”) | |||

| 20 min | 17.00 | 2.00 | 17.00 | 2.00 | |||||||

| Posta | 19.00 | 1.00 | 18.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Percentage fatigue (%) | |||||||||||

| Wasuntarawat, 2010 | Anaerobic exercise (exhaustive sprint) | KP 1.35 g/day vs placebo | Wingate 1 | 43.00 | 13.00 | 40.00 | 15.00 | No differences in percent fatigue during each 30-second sprint were observed between placebo and KP. Percent fatigue during the third Wingate test was significantly (P < .05) greater than during the first Wingate test in both placebo and KP trials | |||

| Wingate 2 | 48.00 | 12.00 | 44.00 | 15.00 | |||||||

| Wingate 3 | 51.00 | 13.00 | 53.00 | 10.00 | |||||||

| Heart rate (BPM) | |||||||||||

| Deema, 2007 | Maximum heart rate | ||||||||||

| Endurance training groups | KP 1.35 g/day vs placebo | Baseline | 181.00 | 0.80 | 179.60 | 0.50 | Significantly increased at week 8 in the placebo group (difference from baseline) | ||||

| 4 weeks | 184.70 | 0.70 | 181.30 | 0.60 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 184.60 | 0.80 | 186.60 | 0.80 | |||||||

| No endurance training groups | Baseline | 185.00 | 2.00 | 180.00 | 2.40 | No significant effects | |||||

| 4 weeks | 199.60 | 0.60 | 176.20 | 2.60 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 186.40 | 1.60 | 181.20 | 1.80 | |||||||

| Wasuntarawat, 2010 | Aerobic exercise (endurance) | KP 1.35 g/day vs placebo | 10 min | 165.00 | 13.00 | 164.00 | 11.00 | Heart rate at 10 and 20 minutes and immediately after exhaustion were also not different between placebo and KP | |||

| 20 min | 174.00 | 10.00 | 172.00 | 9.00 | |||||||

| Posta | 177.00 | 8.00 | 174.00 | 10.00 | |||||||

| Lactate threshold (watt) | |||||||||||

| Deema, 2007 | Endurance training groups | KP 1.35 g/day vs placebo | Baseline | 129.60 | 1.70 | 142.50 | 1.70 | Significantly increased lactate threshold at weeks 4 and 8 in the KP group (difference from baseline) | |||

| 4 weeks | 156.80 | 2.70 | 155.00 | 2.30 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 165.90 | 3.3 0 | 160.00 | 1.80 | |||||||

| No endurance training groups | Baseline | 120.00 | 4.20 | 120.00 | 4.20 | No significant effects from baseline | |||||

| 4 weeks | 118.80 | 5.40 | 118.80 | 6.00 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 118.80 | 2.80 | 106.30 | 3.10 | |||||||

| Hand grip strength test | |||||||||||

| Wattanathorn, 2012 | Right hand (kg) | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 25.06 | 3.01 | 24.53 | 2.55 | No significant effects | |||

| 4 weeks | 25.00 | 2.97 | 24.33 | 2.28 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 24.86 | 3.18 | 24.33 | 2.46 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 23.93 | 3.30 | — | — | No significant effects | |||||

| 4 weeks | 24.60 | 3.13 | — | — | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 24.80 | 3.14 | — | — | |||||||

| Left hand (kg) | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 22.06 | 1.86 | 21.06 | 1.83 | No significant effects | ||||

| 4 weeks | 21.66 | 1.50 | 21.33 | 1.58 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 21.26 | 1.48 | 21.20 | 1.56 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 20.86 | 2.72 | — | — | No significant effects | |||||

| 4 weeks | 21.60 | 2.02 | — | — | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 21.60 | 1.84 | — | — | |||||||

| Promthep, 2015 | Right hand (kg/wt) | KP 180 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 0.65 | 0.09 | 0.63 | 0.07 | Significantly enhanced at weeks 4, 8, and 12 (difference from the placebo group in the same week) and significant difference compared with the baseline score at week 4 | |||

| 4 weeks | 0.70 | 0.09 | 0.66 | 0.07 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 0.68 | 0.10 | 0.63 | 0.07 | |||||||

| 12 weeks | 0.65 | 0.08 | 0.62 | 0.07 | |||||||

| Left hand (kg/wt) | KP 180 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 0.62 | 0.08 | 0.60 | 0.08 | Significantly enhanced at week 8 (difference from the placebo group in the same week) | ||||

| 4 weeks | 0.65 | 0.10 | 0.62 | 0.07 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.59 | 0.08 | |||||||

| 12 weeks | 0.61 | 0.08 | 0.57 | 0.07 | |||||||

| 30-Second chair stand test (seconds) | |||||||||||

| Wattanathorn, 2012 | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 18.33 | 2.58 | 19.13 | 2.79 | No significant effects | ||||

| 4 weeks | 19.00 | 2.77 | 19.26 | 1.43 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 20.00 | 3.11 | 18.93 | 1.70 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 18.60 | 2.52 | — | — | Significantly increased at week 8 compared with baseline | |||||

| 4 weeks | 19.60 | 2.13 | — | — | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 20.66 | 2.28 | — | — | |||||||

| 6-Minute Walk Test (m) | |||||||||||

| Wattanathorn, 2012 | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 571.26 | 33.68 | 567.33 | 33.52 | No significant effects | ||||

| 4 weeks | 570.33 | 38.32 | 598.73 | 31.57 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 575.53 | 36.04 | 571.26 | 32.05 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 572.80 | 32.65 | — | — | Significantly increased at week 8 compared with either baseline or placebo | |||||

| 4 weeks | 575.46 | 34.29 | — | — | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 601.26 | 33.70 | — | — | |||||||

| Tandem stance test (seconds) | |||||||||||

| Wattanathorn, 2012 | Opened eye | ||||||||||

| Right leg is in front | KP 25 mg/day vs Placebo | Baseline | 161.8 | 11.16 | 164.80 | 12.34 | No significant effects | ||||

| 4 weeks | 164.06 | 9.63 | 163.06 | 10.35 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 162.26 | 8.93 | 165.06 | 9.80 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 164.00 | 10.50 | — | — | No significant effects | |||||

| 4 weeks | 166.60 | 6.81 | — | — | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 168.46 | 6.90 | — | — | |||||||

| Left leg is in front | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 111.93 | 7.77 | 112.33 | 11.00 | No significant effects | ||||

| 4 weeks | 112.33 | 11.39 | 110.66 | 10.01 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 111.80 | 10.16 | 109.00 | 10.20 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 108.20 | 11.32 | — | — | No significant effects | |||||

| 4 weeks | 109.33 | 13.62 | — | — | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 111.80 | 13.31 | — | — | |||||||

| Closed eye | |||||||||||

| Right leg is in front | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 31.86 | 10.12 | 33.80 | 9.22 | No significant effects | ||||

| 4 weeks | 32.60 | 7.44 | 30.80 | 10.74 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 32.73 | 7.67 | 31.66 | 10.41 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 31.26 | 11.09 | — | — | No significant effects | |||||

| 4 weeks | 31.86 | 9.33 | — | — | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 33.40 | 8.94 | — | — | |||||||

| Left leg is in front | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 20.93 | 3.41 | 18.80 | 3.60 | No significant effects | ||||

| 4 weeks | 21.33 | 3.79 | 19.86 | 5.01 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 21.26 | 3.19 | 21.20 | 4.57 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 20.46 | 4.24 | — | — | No significant effects | |||||

| 4 weeks | 21.26 | 4.58 | — | — | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 22.06 | 3.93 | — | — | |||||||

| A sit-and-reach test (cm) | |||||||||||

| Promthep, 2015 | KP 180 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 17.98 | 4.60 | 16.14 | 4.93 | Significant difference compared with the baseline score at week 4 (both the treatment and placebo groups) | ||||

| 4 weeks | 16.43 | 5.15 | 14.64 | 4.92 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 16.88 | 5.19 | 14.61 | 5.24 | |||||||

| 12 weeks | 18.28 | 5.10 | 17.01 | 4.55 | |||||||

| A back-and-leg strength test (kg/wt) | |||||||||||

| Promthep, 2015 | KP 180 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 2.77 | 0.54 | 2.45 | 0.39 | No significant effects | ||||

| 4 weeks | 2.68 | 0.55 | 2.45 | 0.51 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 2.77 | 0.55 | 2.44 | 0.40 | |||||||

| 12 weeks | 2.79 | 0.59 | 2.53 | 0.52 | |||||||

| A 40-yard technical test (seconds) | |||||||||||

| Promthep, 2015 | KP 180 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 11.61 | 0.07 | 11.99 | 0.86 | Significantly decreased at week 12 compared with the baseline | ||||

| 4 weeks | 12.06 | 1.16 | 12.34 | 1.33 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 11.50 | 0.74 | 11.46 | 0.75 | |||||||

| 12 weeks | 10.08 | 0.47 | 10.47 | 0.90 | |||||||

| A 50-metre sprint test (seconds) | |||||||||||

| Promthep, 2015 | KP 180 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 6.24 | 0.31 | 6.29 | 0.37 | No significant effects in both groups. No significant differences between the groups | ||||

| 4 weeks | 6.26 | 0.31 | 6.33 | 0.49 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 6.37 | 0.26 | 6.50 | 0.50 | |||||||

| 12 weeks | 6.33 | 0.24 | 6.47 | 0.52 | |||||||

| A cardiorespiratory fitness test VO2 max (mL/kg/min) | |||||||||||

| Promthep, 2015 | KP 180 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 45.09 | 9.88 | 45.09 | 9.96 | Significantly increased cardiorespiratory fitness, as indicated by VO2 max values at week 12. No significant difference between the groups | ||||

| 4 weeks | 46.95 | 7.61 | 47.85 | 10.08 | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 49.40 | 8.40 | 48.34 | 7.17 | |||||||

| 12 weeks | 51.05 | 8.40 | 47.10 | 8.45 | |||||||

| Pain indicators | |||||||||||

| Chalee, 2010 | Pain severity | KP 7% w/w vs analgesic cream | Baseline | 8.11 | 0.99 | 8.15 | 1.09 | Significantly decreased at week 4 compared with the baseline (both the treatment and placebo groups). No significant difference between the groups | |||

| 4 weeks | 6.80 | 0.76 | 6.87 | 0.65 | |||||||

| Circumference of knee joint (cm) | Baseline | 37.91 | 2.75 | 37.15 | 3.00 | ||||||

| 4 weeks | 37.03 | 2.56 | 36.30 | 2.64 | |||||||

| Range of motion of knee joint (ROM) | Baseline | 110.57 | 9.45 | 109.39 | 10.66 | ||||||

| 4 weeks | 117.43 | 5.86 | 116.21 | 6.62 | |||||||

| Modified WOMAC score | Baseline | 40.31 | 6.63 | 39.97 | 6.02 | ||||||

| 4 weeks | 39.29 | 5.84 | 39.00 | 5.50 | |||||||

| Energy expenditure | |||||||||||

| Matsushita, 2015 | Energy expenditure change (kJ/day) | ||||||||||

| All | KP 100 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 6213.00 | 143.00 | 6196.00 | 150.00 | No significant in the placebo group but significant difference between the groups at 30 and 60 minutes, difference from baseline and maximal rise at 60 minutes | ||||

| 60 minutes | 6442.00 | 212.00 | NR | NR | |||||||

| High-BAT | KP 180 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 6076.00 | 184.00 | 6103.00 | 184 | No significant in the placebo group but significant difference between the groups at 30 and 60 minutes, difference from baseline at 30, 60, 90 minutes and maximal rise at 60 minutes | ||||

| 60 minutes | 6427.00 | 234.00 | NR | NR | |||||||

| Low-BAT | KP 180 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 6418.00 | 223.00 | 6334.00 | 261.00 | No significant effects | ||||

| 60 minutes | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Erectile response | |||||||||||

| Wannanon, 2012 | Penile circumference (cm) | ||||||||||

| Resting state | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 9.40 | 0.79 | 9.00 | 0.73 | No significant effects | ||||

| 1 month | 9.00 | 0.79 | 8.70 | 0.59 | |||||||

| 2 months | 9.40 | 0.79 | 8.80 | 0.59 | |||||||

| Delayb | 9.15 | 3.10 | 9.15 | 3.10 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 9.20 | 0.69 | 9.00 | 0.73 | After 1 and 2 months of treatment, significant increase in the length and width of penis when compared with the placebo treated group | |||||

| 1 month | 10.20 | 0.79 | 8.70 | 0.59 | |||||||

| 2 months | 10.15 | 0.79 | 8.80 | 0.59 | |||||||

| Delayb | 9.65 | 2.71 | 9.15 | 3.10 | |||||||

| Erection state | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 10.90 | 3.87 | 11.50 | 3.87 | No significant effects | ||||

| 1 month | 10.50 | 3.68 | 10.60 | 3.10 | |||||||

| 2 months | 11.50 | 4.26 | 11.80 | 2.71 | |||||||

| Delayb | 11.70 | 3.10 | 11.70 | 2.71 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 10.80 | 4.26 | 11.50 | 3.87 | After 1 and 2 months of treatment, significant increase in the width when compared with the placebo treated group | |||||

| 1 month | 12.10 | 4.26 | 10.60 | 3.10 | |||||||

| 2 months | 11.90 | 4.26 | 11.80 | 2.71 | |||||||

| Delayb | 11.70 | 0.39 | 11.70 | 2.71 | |||||||

| Penile length (cm) | |||||||||||

| Resting state | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 9.70 | 4.26 | 9.95 | 7.55 | No significant effects | ||||

| 1 month | 9.65 | 3.87 | 9.90 | 3.49 | |||||||

| 2 months | 10.90 | 3.87 | 10.00 | 3.10 | |||||||

| Delayb | 10.60 | 3.49 | 10.25 | 0.07 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 9.40 | 4.07 | 9.95 | 7.55 | After 1 and 2 months of treatment, significant increase in the length when compared with the placebo treated group | |||||

| 1 month | 11.25 | 3.49 | 9.90 | 3.49 | |||||||

| 2 months | 11.10 | 2.71 | 10.00 | 3.10 | |||||||

| Delayb | 10.65 | 3.49 | 10.25 | 0.07 | |||||||

| Erection state | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 12.50 | 5.27 | 13.10 | 4.96 | No significant effects | ||||

| 1 month | 12.95 | 4.03 | 12.20 | 3.87 | |||||||

| 2 months | 13.10 | 4.34 | 12.40 | 4.18 | |||||||

| Delayb | 13.55 | 3.87 | 13.20 | 2.79 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 12.90 | 4.34 | 13.10 | 4.96 | After 1 and 2 months of treatment, significant increase in the length when compared with the placebo treated group | |||||

| 1 month | 13.75 | 4.34 | 12.20 | 3.87 | |||||||

| 2 months | 13.90 | 4.03 | 12.40 | 4.18 | |||||||

| Delayb | 13.50 | 4.65 | 13.20 | 2.79 | |||||||

| Latency time (mins) | |||||||||||

| Erection state | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 10.90 | 13.94 | 11.60 | 12.39 | No significant effects | ||||

| 1 month | 8.60 | 12.39 | 11.70 | 11.81 | |||||||

| 2 months | 8.00 | 12.39 | 10.00 | 10.65 | |||||||

| Delayb | 7.80 | 0.59 | 10.90 | 12.78 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 10.40 | 9.30 | 11.60 | 12.39 | Significantly decreased the response latency to sexual erotic stimuli and still showed the significant changes during the delay period | |||||

| 1 month | 5.50 | 7.17 | 11.70 | 11.81 | |||||||

| 2 months | 5.50 | 6.58 | 10.00 | 10.65 | |||||||

| Delayb | 7.40 | 6.20 | 10.90 | 12.78 | |||||||

| Serum hormones concentrations | |||||||||||

| Testosterone (ng/mL) | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 4.11 | 1.56 | 4.14 | 0.92 | No significant effects | ||||

| Single dose | 4.79 | 4.63 | 5.28 | 2.76 | |||||||

| 1 month | 5.11 | 3.13 | 5.92 | 5.49 | |||||||

| 2 months | 4.64 | 1.22 | 5.65 | 1.23 | |||||||

| Delayb | 5.71 | 2.38 | 5.14 | 0.92 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 4.11 | 1.30 | 4.14 | 0.92 | No significant effects | |||||

| Single dose | 4.89 | 2.63 | 5.28 | 2.76 | |||||||

| 1 month | 4.26 | 0.83 | 5.92 | 5.49 | |||||||

| 2 months | 5.74 | 2.60 | 5.65 | 1.23 | |||||||

| Delayb | 6.06 | 3.19 | 5.14 | 0.92 | |||||||

| FSH (IU/L) | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 8.80 | 4.29 | 7.88 | 4.34 | No significant effects | ||||

| Single dose | 7.35 | 4.23 | 6.73 | 2.54 | |||||||

| 1 month | 7.23 | 5.37 | 6.52 | 5.51 | |||||||

| 2 months | 7.96 | 3.32 | 5.95 | 2.34 | |||||||

| Delayb | 8.81 | 5.12 | 5.88 | 3.34 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 7.53 | 2.92 | 7.88 | 4.34 | No significant effects | |||||

| Single dose | 6.14 | 2.26 | 6.73 | 2.54 | |||||||

| 1 month | 6.29 | 2.25 | 6.52 | 5.51 | |||||||

| 2 months | 6.01 | 2.79 | 5.95 | 2.34 | |||||||

| Delayb | 7.03 | 2.35 | 5.88 | 3.34 | |||||||

| LH (IU/L) | KP 25 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 7.25 | 5.90 | 7.14 | 5.62 | No significant effects | ||||

| Single dose | 8.12 | 2.72 | 7.59 | 3.21 | |||||||

| 1 month | 7.04 | 5.34 | 7.30 | 4.24 | |||||||

| 2 months | 8.48 | 4.64 | 7.82 | 2.34 | |||||||

| Delayb | 8.72 | 4.67 | 8.14 | 3.23 | |||||||

| KP 90 mg/day vs placebo | Baseline | 6.99 | 4.37 | 7.14 | 5.62 | No significant effects | |||||

| Single dose | 7.65 | 1.88 | 7.59 | 3.21 | |||||||

| 1 month | 8.55 | 3.64 | 7.30 | 4.24 | |||||||

| 2 months | 7.41 | 4.67 | 7.82 | 2.34 | |||||||

| Delayb | 8.82 | 4.44 | 8.14 | 3.23 | |||||||

Abbreviations: KP, Kaempferia parviflora; VO2, oxygen consumption; ROM, range of motion; high-BAT, high brown adipose tissue; low-BAT, low brown adipose tissue; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone.

aPost: immediately after exercise.

bDelay: 1 month after the cessation of KP administration.

Figure 3.

Forest plot illustrating the effect of Krachaidum on hand grip strength.

Clinical Effects of Krachaidum on Erectile Response

Only one randomized controlled trial compared Krachaidum with placebo in human subjects on erectile response.34 Subjects receiving Krachaidum 25 mg/day (n = 15), or 90 mg/day (n = 15), were compared with those receiving placebo (n = 15) for 8 weeks of study period. They found that Krachaidum at a dose of 90 mg/day significantly decreased the response latency time to sexual erotic stimulation and still showed significant changes during the delay period. In addition, after 1 month and 2 months, the Krachaidum group at a dose of 90 mg/day experienced a statistically significant increase in length and width of penis both in resting state and erection state compared with the placebo group. Krachaidum showed no effects on serum hormones (ie, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone; Table 2).

Clinical Effects of Krachaidum on Pain Indicators

A study by Chalee35 compared Krachaidum cream with analgesic cream on pain reduction indicators. Pain severity, circumference of knee joint, range of motion of knee joint, and modified Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index score were assessed and compared within the group from baseline, or between the groups with analgesic cream. Comparing with baseline, the results in both groups showed significantly reduce pain in all indicators at 4 weeks. On the contrary, comparing with analgesic cream, Krachaidum cream showed nonsignificant different (Table 2).

Clinical Effects of Krachaidum on Energy Expenditure

A study by Matsushita et al36 evaluated the effect of 2 doses of Krachaidum 100 mg/day or 180 mg/day on energy expenditure change compared with placebo. They found that when comparing with baseline, Krachaidum showed significant increase in energy expenditure at 30 minutes and 60 minutes in both groups. However, compared with placebo, no significant additional benefit of Krachaidum on energy expenditure was found (Table 2).

Discussion

This systematic review provides a critical summary of clinical evidence of Krachaidum for all indications. We found a wide variety of use of Krachaidum including physical or exercise performance, erectile response, pain indicators, and energy expenditure. The methodological quality of the 7 randomized controlled trials included in the systematic review was high according to Jadad score, and was ranked as unclear according to Cochrane risk of bias tool. From the included clinical trials, the benefits of Krachaidum remained inconclusive.

Our pooled effect on physical or exercise performance outcomes showed that Krachaidum 90 to 180 mg/day significantly enhanced hand grip strengths compared with placebo.32,33 This might be explained by the increased blood flow effect of Krachaidum.37 A previous study demonstrated that Krachaidum supplementation could increase blood flow to the organs due to vasorelaxation induction. This partly was mediated through cyclooxygenase and nitric oxide–dependent pathways,38 and Krachaidum also showed anti-inflammatory effects.37,39,40 Therefore, the combination effect of increased blood flow and anti-inflammatory effects may facilitate muscle strength.32,33

For erectile response outcome, although only one study was included,34 it showed that subjects receiving Krachaidum 90 mg/day exhibited a significant enhancement in all parameters (ie, response latency time to visual erotic stimuli, size and length of penis both in flaccid and erectile states) after 1 and 2 months of treatment compared with placebo. The authors explained that the effects involved nitric oxide. The experimental studies reported that Krachaidum extract could induce an increase of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and protein expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cell.41 Thus, abundance of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in endothelium of penile vasculature and sinusoidal endothelium within the corpora carvernosa might increase penile erection.42–44

For pain indicators, a study comparing Krachaidum cream with analgesic cream in knee osteoarthritis was found.35 Although the findings demonstrated significant pain reduction in all indicators at 4 weeks compared with baseline, but there was no significant difference when compared with analgesic cream. Since anti-inflammatory effect was studied only using oral administration of Krachaidum,40,45,46 the mechanism of Krachaidum cream on pain reduction was still unclear.

Furthermore, the effect of Krachaidum on energy expenditure has been linked to the activity of brown adipose tissue, a site of nonshivering thermogenesis.47 A previous study found that the components of Krachaidum extract activate hormone-sensitive lipase in adipocyte.48 Furthermore, 5,7-dimenthoxyflavone, the major flavonoid in Krachaidum extract, was demonstrated to have a the potent inhibitory effect on eAMP-degrading enzyme.20 Since eAMP is a signal of hormone-sensitive lipase in adipocyte, it activates brown adipose tissue thermogenesis. Thus, it is possible that the brown adipose tissue–mediated thermogenic effect of Krachaidum extract exist via the inhibition of phosphodiesterase in brown adipose tissue. A study showed that Krachaidum extract could potentially increase whole-body energy expenditure probably through the activation of brown adipose tissue, which might benefit as an antiobesity regimen.36

Considering safety issues, adverse events were not reported among all included studies. An animal study of Krachaidum extract on chronic toxicity was conducted.23 They randomly divided 120 Wistar rats into 5 groups, 24 rats each (12 males and 12 females). Then, 3 treatment groups were orally administered with Krachaidum extract at doses of 5, 50, and 500 mg/kg/day for 6 months, respectively, which were equivalent to 1, 10, and 100 times that of human use, while 2 control groups were orally given distilled water and 1.0% tragacanth, respectively. The results showed that the histopathological study of visceral organs revealed no remarkable lesions related to the toxicity of Krachaidum extract.

The limitations of this study should be noted. First, we found limited number of studies to be included. Thus, pooling effect is impossible. Even when possible (ie, hand grip strengths), only 2 studies were pooled; therefore, conclusive findings could not be determined. Second, this systematic review had diversity of Krachaidum dosage regimens (ie, from 25 mg/day to 1.35 g/day), dosage forms (ie, capsule, cream), or extraction method (60% or 95% ethanol extraction) across studies. Applying the results to clinical practice is limited.

Conclusion

In summary, although various indications of Krachaidum were found with varying qualities of evidence, the positive benefits of Krachaidum were reported, and adverse events were not found. As a very small number of studies were included, it would be difficult to make reliable conclusions. Additional clinical studies with larger sample sizes are needed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Ratree Sawangjit for her valuable comments.

Authors’ Note: The funding agency had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the article; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author Contributions: SS, PD, and NC conceptualized the study and developed the inclusion criteria. SS, PW, and PR collected the data, analyzed the data, developed the table, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SS developed the figure and analyzed the data. All authors conceptualized the study and reviewed the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: AC is currently a government official under the Department for Development of Thai Traditional and Alternative Medicine, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand. The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors received financial support from Department for Development of Thai Traditional and Alternative Medicine, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand.

Ethical Approval: This study did not warrant institutional review board review as no human subjects were involved.

References

- 1. Wuttidharmmavej W. Rattanakosin Pharmaceutical Scripture. Bangkok, Thailand: Wuttidharmmavej; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tewtrakul S, Subhadhirasakul S, Kummee S. Anti-allergic activity of compounds from Kaempferia parviflora. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;116:191–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tewtrakul S, Subhadhirasakul S. Anti-allergic activity of some selected plants in the Zingiberaceae family. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;109:535–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tewtrakul S, Subhadhirasakul S, Karalai C, Ponglimanont C, Cheenpracha S. Anti-inflammatory effects of compounds from Kaempferia parviflora and Boesenbergia pandurata. Food Chem. 2009;115:534–538. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Azuma T, Kayano SI, Matsumura Y, Konishi Y, Tanaka Y, Kikuzaki H. Antimutagenic and (alpha)-glucosidase inhibitory effects of constituents from Kaempferia parviflora. Food Chem. 2011;125:471–475. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wattanathorn J, Tong-Un T, Muchimapura S, Wannanon P, Sripanidkulchai B, Phachonpai W. Anti-stress effects of Kaempferia parviflora in immobilization subjected rats. Am J Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;8:31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sawasdee P, Sabphon C, Sitthiwongwanit D, Kokpol U. Anticholinesterase activity of 7-methoxyflavones isolated from Kaempferia parviflora. Phytother Res. 2009;23:1792–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yenjai C, Prasanphen K, Daodee S, Wongpanich V, Kittakoop P. Bioactive flavonoids from Kaempferia parviflora. Fitoterapia. 2004;75:89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kummee S, Tewtrakul S, Subhadhirasakul S. Antimicrobial activity of the ethanol extract and compounds from the rhizomes of Kaempferia parviflora. Songklanakarin J Sci Technol. 2008;30:463–466. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Banjerdpongchai R, Suwannachot K, Rattanapanone V, Sripanidkulchai B. Ethanolic rhizome extract from Kaempferia parviflora Wall. ex. Baker induces apoptosis in HL-60 cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9:595–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tewtrakul S, Subhadhirasakul S. Effects of compounds from Kaempferia parviflora on nitric oxide, prostaglandin E2 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha productions in RAW264.7 macrophage cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120:81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leardkamolkarn V, Tiamyuyen S, Sripanidkulchai BO. Pharmacological activity of Kaempferia parviflora extract against human bile duct cancer cell lines. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10:695–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rujjanawate C, Kanjanapothi D, Amornlerdpison D, Pojanagaroon S. Anti-gastric ulcer effect of Kaempferia parviflora. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102:120–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Malakul W, Ingkaninan K, Sawasdee P, Woodman OL. The ethanolic extract of Kaempferia parviflora reduces ischaemic injury in rat isolated hearts. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tep-Areenan P, Sawasdee P, Randall M. Possible mechanisms of vasorelaxation for 5,7-dimethoxyflavone from Kaempferia parviflora in the rat aorta. Phytother Res. 2010;24:1520–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Akase T, Shimada T, Terabayashi S, Ikeya Y, Sanada H, Aburada M. Antiobesity effects of Kaempferia parviflora in spontaneously obese type II diabetic mice. J Nat Med. 2011;65:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sudwan P, Saenphet K, Saenphet S, Suwansirikul S. Effect of Kaempferia parviflora Wall. ex. Baker on sexual activity of male rats and its toxicity. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006;37(suppl 3):210–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wattanapitayakul SK, Suwatronnakorn M, Chularojmontri L, et al. Kaempferia parviflora ethanolic extract promoted nitric oxide production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110:559–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chaturapanich G, Chaiyakul S, Verawatnapakul V, Yimlamai T, Pholpramool C. Enhancement of aphrodisiac activity in male rats by ethanol extract of Kaempferia parviflora and exercise training. Andrologia. 2008;44(suppl 1):323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Temkitthawon P, Hinds TR, Beavo JA, et al. Kaempferia parviflora, a plant used in traditional medicine to enhance sexual performance contains large amounts of low affinity PDE5 inhibitors. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:1437–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sutthanut K, Sripanidkulchai B, Yenjai C, Jay M. Simultaneous identification and quantitation of 11 flavonoid constituents in Kaempferia parviflora by gas chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2007;1143:227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chuthaputti A. Krachai Dam: a champion herbal product. J Thai Traditional Alter Med. 2013;11:4–16. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chivapat S, Chavalittumrong P, Attawish A, Rungsipipat A. Chronic toxicity study of Kaempferia parviflora Wall ex. extract. Thai J Vet Med. 2010;40:377–383. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Department for Development of Thai Traditional and Alternative Medicine. The 10th national herb exhibition Nonthaburi: Ministry of Public Health. http://www.dtam.moph.go.th/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=344:pr0175&catid=8&Itemid=114. Accessed December 9, 2015.

- 25. Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. http://handbook.cochrane.org/. Accessed September 7, 2016.

- 26. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269, W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gagnier JJ, Boon H, Rochon P, Moher D, Barnes J, Bombardier C. Reporting randomized, controlled trials of herbal interventions: an elaborated CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:364–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Deema P. Effect of Kaempferia parviflora and Endurance Training on Lactate Threshold in Humans. Phitsanulok, Thailand: Naresuan University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wasuntarawat C, Pengnet S, Walaikavinan N, et al. No effect of acute ingestion of Thai ginseng (Kaempferia parviflora) on sprint and endurance exercise performance in humans. J Sports Sci. 2010;28:1243–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wattanathorn J, Muchimapura S, Tong-Un T, Saenghong N, Thukhum-Mee W, Sripanidkulchai B. Positive modulation effect of 8-week consumption of Kaempferia parviflora on health-related physical fitness and oxidative status in healthy elderly volunteers. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:732816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Promthep K, Eungpinichpong W, Sripanidkulchai B, Chatchawan U. Effect of Kaempferia parviflora extract on physical fitness of soccer players: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2015;21:100–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wannanon P, Wattanathorn J, Tong-Un T, et al. Efficacy assessment of Kaempferia parviflora for the management of erectile dysfunction. Online J Biol Sci. 2012;12:149–155. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chalee S. Study of Efficacy and Anti-Inflammatory Effect of K. parviflora Extract Cream in Osteoarthritis of Knee. Khon Kaen, Thailand: Khon Kaen University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Matsushita M, Yoneshiro T, Aita S, et al. Kaempferia parviflora extract increases whole-body energy expenditure in humans: roles of brown adipose tissue. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2015;61:79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chaturapanich G, Chaiyakul S, Verawatnapakul V, Pholpramool C. Effects of Kaempferia parviflora extracts on reproductive parameters and spermatic blood flow in male rats. Reproduction. 2008;136:515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tep-Areenan P, Ingkaninan K, Randall MD. Mechanisms of Kaempferia parviflora extract (KPE)-induced vasorelaxation in the rat aorta. Asian Biomed. 2010;4:103–111. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sae-wong C, Tansakul P, Tewtrakul S. Anti-inflammatory mechanism of Kaempferia parviflora in murine macrophage cells (RAW 264.7) and in experimental animals. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124:576–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sae-Wong C, Matsuda H, Tewtrakul S, et al. Suppressive effects of methoxyflavonoids isolated from Kaempferia parviflora on inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression in RAW 264.7 cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136:488–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guohua H, Yanhua L, Rengang M, Dongzhi W, Zhengzhi M, Hua Z. Aphrodisiac properties of Allium tuberosum seeds extract. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122:579–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tajuddin Ahmad S, Latif A, Qasmi IA. Aphrodisiac activity of 50% ethanolic extracts of Myristica fragrans Houtt. (nutmeg) and Syzygium aromaticum (L) Merr. & Perry. (clove) in male mice: a comparative study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2003;3:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tajuddin Ahmad S, Latif A, Qasmi IA. Effect of 50% ethanolic extract of Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & Perry. (clove) on sexual behaviour of normal male rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2004;4:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tajuddin Ahmad S, Latif A, Qasmi IA, Amin KM. An experimental study of sexual function improving effect of Myristica fragrans Houtt. (nutmeg). BMC Complement Altern Med. 2005;5:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Horigome S, Yoshida I, Ito S, et al. Inhibitory effects of Kaempferia parviflora extract on monocyte adhesion and cellular reactive oxygen species production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells [published online December 24, 2015]. Eur J Nutr. doi:10.1007/s00394-015-1141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Horigome S, Yoshida I, Tsuda A, et al. Identification and evaluation of anti-inflammatory compounds from Kaempferia parviflora. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2014;78:851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yoshino S, Kim M, Awa R, Kuwahara H, Kano Y, Kawada T. Kaempferia parviflora extract increases energy consumption through activation of BAT in mice. Food Sci Nutr. 2014;2:634–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Okabe Y, Shimada T, Horikawa T, et al. Suppression of adipocyte hypertrophy by polymethoxyflavonoids isolated from Kaempferia parviflora. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:800–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]