Abstract

Depression is a prevalent disorder among patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome. The current study was performed to evaluate the effect of a traditional Persian medicine product, anise oil, in removing the symptoms of mild to moderate depression in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. In a randomized double-blinded active and placebo controlled clinical trial, 120 participants with mild to moderate depression according to the Beck Depression Inventory–II total scores were categorized into 3 equal groups and received anise oil, Colpermin, and placebo. The results at the end of trial (week 4) and follow-up (week 6) demonstrated significant priority against active and placebo groups. Although the mechanism is unknown yet, anise oil could be a promising choice of treatment for depressed patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

Keywords: depression, traditional Persian medicine, anise, irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal ailment worldwide. It is characterized by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits. It has a rather high prevalence of 21.5% in Iran, and there is a dire need for a multidisciplinary approach for treatment.1,2 Because of the sociocultural issues involved in IBS characteristics, the diagnosis differs in various countries3; however, IBS could increase the risk of depression and other psychiatric disorders such as (chronic) anxiety at a global level.4 In view of this relationship, psychological factors seem to have an essential role in the creation and progress of IBS.5

Depression is a prevalent psychiatric problem in IBS patients seeking treatment while the role of brain-gut interaction has found remarkable evidence in the literature: the association of IBS and depression appears to be fundamental.6,7 Different herbal medicaments have been introduced in literature for the treatment of depression solely or in combination with chemical antidepressants.8–11 Nevertheless, there is no report on anise (Pimpinella anisum L) except for its effect on rats’ brains as an anticonvulsant and neuroprotective agent.12 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first survey to evaluate the effects of a herbal product on depression of IBS patients. Considering adverse reactions and destructive effects of chemical antidepressants,8 loss of clinical data on anise antidepressant properties, comprehensive reputation of herbal medicaments,13 and the research team’s aim of introducing a less expensive drug, this study was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of Pimpinella anisum L in the treatment of mild to moderate depression in patients with IBS.

Patients and Methods

Trial Design

This was a parallel randomized controlled clinical trial with 3 arms receiving enteric-coated capsules of anise oil (AnisEncap), peppermint oil (Colpermin) as reference product, and placebo. One hundred and twenty patients were allocated to 3 parallel groups (enteric-coated capsules of anise oil, Colpermin, and placebo). Patients received 3 capsules of 200 mg AnisEncap, 187 mg Colpermin, or, alternatively, placebo on a daily basis before each meal for 4 weeks. Follow-up time was set at the next 2 weeks.

All participants (120 patients with diagnosis of IBS) ranging in age from 20 to 50 years attended the Motahhari Clinic, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. They were enrolled in the trial from August 2014 to February 2015. Diagnosis of IBS was confirmed according to Rome III criteria14 by examination of a registered gastroenterologist with more than 15 years of experience.

Meeting the Rome III Modular criteria, all patients under the age of 50 years were asked to have a sigmoidoscopy performed. For those patients aged 50 years and older, it was mandatory to have had a colonoscopy within the previous 5 years.15

Exclusion criteria comprised sever form of depression, pregnancy or breast milking mothers, abnormal baseline laboratory tests, history of previous abdominal surgery, confirmed organic disorders of the large or small bowel, any negative symptoms in favor of gastrointestinal malignancies like rectal bleeding,16 diagnosis of any medical condition associated with constipation (other than IBS) or mechanical obstruction, any form of diagnosed cancer, and abuse of alcohol or any types of narcotic or antidepressant drugs.14

Ethical Aspects

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (SUMS, CT-92-6460). The trial was registered in Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT201205069651N1). The patients signed a written informed consent at the baseline visit of this trial.

Outcome Evaluations

Reduction of total score (ranging from 0 to 63) of the Beck Depression Inventory–II is a form of assessing depression in research projects and has been validated in different populations including Iran.10,17 The Beck Depression Inventory–II is a multiple self-report measure designed to evaluate depression in adult patients.18 In the present study, the participants expressed their depressive symptoms at the beginning of the trial, 4 weeks later, and 2 weeks after the end of the intervention in the follow-up phase.

AnisEncap and Placebo

According to traditional Persian medicine textbooks, anise has a quality to elate mood and, consequently, ameliorates depression. Pimpinella anisum L (Apiaceae) was cultivated in February 2012 (and collected after 4 months and approved with Herbarium Voucher No. 772(SFPH) at the Department of Traditional Pharmacy, Shiraz School of Pharmacy). Anise oil was obtained from the dry ripe fruits of the aforesaid sample by conventional steam distillation (Clevenger apparatus) for extracting volatile oils.19 Then, anise oil was evaluated and confirmed by gas chromatography-flame ionization detection with reference to trans-anethole (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO).20

AnisEncap formula was considered according to the compositions described in traditional Persian medicine pharmacopoeias like Qarabadin-e-kabir.21 Each hard gelatin capsule (size 0) was filled with 200 mg anise oil oleogel containing beeswax (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), peanut oil (Sigma-Aldrich), and Aerosil (Evonik, Essen, Germany). Later, the capsules were capped and sealed. Placebo capsules were prepared similarly except for incorporating anise oil in the formulation.

Quality Control

The formulation passed all quality checks in terms of potency, uniformity of content, chemical stability during storage, and microbial limits before the beginning of the trial. Aforementioned tests were performed in Shiraz School of Pharmacy and registered as part of university regulations.

Randomization and Blinding

All the experimental medications (AnisEncap, Colpermin, and placebo capsules) were similar in size, color, package, and labeling. Participants were categorized into 3 groups (case, placebo, and active control) by block randomization, assigning 40 patients to each group. Not only the researchers and the patients but also data analysts were blinded to the drug allocations.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics were compared using χ2 test for categorical parameters and the analysis of variance for quantitative variables. Data are described as mean with 95% confidence intervals.

Beck Depression Inventory–II overall scores were summarized descriptively by the treatment group (according to mean and standard deviation). The significance level for P value was set at .05.

Results and Discussion

A total of 120 patients were categorized into 3 groups of treatment, placebo, and active control groups equally. The mean ± SD for age in treatment, active control, and placebo groups were 34.15 ± 9.29, 35.00 ± 10.13, and 32.35 ± 7.24, respectively (P = .405). The duration of their main illness (IBS) was 6.72 ± 4.28 years (mean ± SD) for those who received the treatment, 5.47 ± 3.77 years for those in the active control group, and 5.25 ± 2.27 years for those in the placebo group (P = .139). Body mass index was 71.90 ± 9.73 kg/m2 in the placebo group, 73.00 ±10.74 kg/m2 in the Colpermin group, and 72.62 ± 11.14 kg/m2 in AnisEncap consumers, again without any significant difference (P = .894).

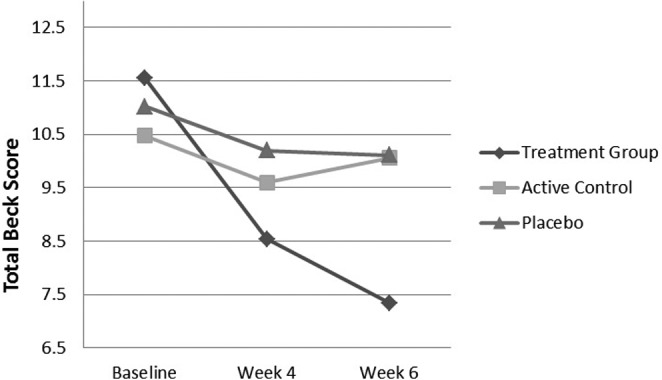

There was no significant difference among basic characteristics such as gender, educational level, job, marital and dwelling status assessed (Table 1). All groups showed no significant change in terms of Beck Depression Inventory–II scores (Table 2). At the end of the trial (4 weeks) and in the follow-up time (2 weeks later), there was a statistically significant difference among patients receiving AnisEncap, Colpermin, and placebo. Last, the treatment group turned out to be significantly more effectively treated as compared with active and placebo groups at the study completion and follow-up times (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Demographic Data Among Treatment, Active Control, and Placebo Groups.

| Demographic Features | Treatment Group (n = 40) | Active Control Group (n = 40) | Placebo Group (n = 40) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | .792 | ||||||

| Male | 19 | 47.5 | 20 | 50.0 | 22 | 55.0 | |

| Female | 21 | 52.5 | 20 | 50.0 | 18 | 45.0 | |

| Educational level | .119 | ||||||

| High school diploma and less | 9 | 22.5 | 14 | 35.0 | 11 | 27.5 | |

| Bachelor of arts (BA) | 24 | 60.0 | 17 | 42.5 | 14 | 35.0 | |

| Higher than BA university education | 7 | 17.5 | 9 | 22.5 | 15 | 37.5 | |

| Job | .644 | ||||||

| Employee | 19 | 47.5 | 18 | 45.0 | 15 | 37.5 | |

| Self-employed | 13 | 32.5 | 12 | 30.0 | 18 | 45.0 | |

| Unemployed | 8 | 20 | 10 | 25.0 | 7 | 17.5 | |

| Marital status | .933 | ||||||

| Single | 11 | 27.5 | 10 | 22.5 | 13 | 32.5 | |

| Married | 17 | 42.5 | 17 | 42.5 | 14 | 35.0 | |

| Divorced | 12 | 30.0 | 13 | 32.5 | 13 | 32.5 | |

| Dwelling status | 0.07 | ||||||

| Owner | 25 | 62.5 | 30 | 75.0 | 34 | 85.0 | |

| Renter | 15 | 37.5 | 10 | 25.0 | 6 | 15.0 | |

Table 2.

Data of the Trial Process.

| Time of Evaluation | AnisEncap | Colpermin | Placebo | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beginning, mean ± SD | n = 40; 11.55 ± 10.07 | n = 40; 10.47 ± 7.22 | n = 40; 11.02 ± 6.74 | .84 |

| The end (4 weeks), mean ± SD | n = 39; 8.54 ± 9.47 | n = 38; 9.60 ± 6.68 | n = 39; 10.20 ± 6.62 | <.001 |

| Follow-up (2 weeks), mean ± SD | n = 38; 7.34 ± 9.94 | n = 33; 10.06 ± 7.28 | n = 37; 10.11 ± 6.79 | <.001 |

Figure 1.

The Trend of Total Beck Depression Inventory Scores in Treatment, Active Control, and Placebo Groups at Baseline, at the End of the Trial, and at the Follow-up Phase.

Considering the final results, most of the patients completed the trial in both finishing and follow-up times. There was no major adverse effect or life-threatening report during the trial or in the follow-up period.

Anise oil improved the total score of Beck Depression Inventory–II in patients suffering from IBS in comparison to active control and placebo significantly. The mechanism of action by traditional Persian medicine practitioners’ view is clear. Depression is an ailment related to imbalance of psychic faculty (Quwwat-e-nafsaniya) and preponderance of black bile. Quwwat-e-nafsaniya obtains its matter from spirit of the heart (Rooh-e-haivaniya). Anise oil is a proper tonic for heart and spirit of the heart. According to traditional Persian medicine treatment procedures, depression has cold nature and the spirit is almost motionless in this mental disorder. Anise oil is warm enough to heat the spirit and elevate the mood (Mofarrih). Therefore, the treatment approach should be focused on strengthening of psychic faculty and/or purifying excess black bile.22–24 Consequently, herbal medicines such as saffron and anise with such a quality could be effective in alleviating the symptoms of depression.21,25

The trend of natural products and herbal medicine consumption for treatment of depression is growing worldwide. Different mechanisms of action for herbs have been proposed and some have passed experimental or clinical proofs.26 Safflower (Carthamus tinctorious L) showed significant efficacy to be used as an alternative therapeutic agent for patients suffering from depressive disorders in an experimental study. This herbal product was as effective as nortriptyline, an eminent standard antidepressant medicine.27 In Mexican traditional medicine, hydroalcoholic (60% ethanol) extract of Salvia elegans Vahl from the family Lamiaceae has also demonstrated antidepressant effect in mice.28 The mechanism of action in these experimental models is not perceptibly clear.

Jollab (a mixture of rose water, saffron, and candy sugar) showed the same effect on patients decreasing the total score of the Beck Questionnaire after a 4-week trial. The mean of the total score before the trial was higher in that study compared to the current one; yet there was no follow-up assessment and active control group for the Jollab trial.10 The similarity in response may be due to the active ingredients in herbal medicaments that act alone or in a synergistic form. The major component of anise oil is trans-anethole (as confirmed in our trial by gas chromatography method), without any documents for confirming its effect on depression in the literature.20 Drug-herb interaction while using with central nervous system drugs is also likely.29

Yang et al assessed the efficacy of 2 traditional Chinese medicine products in 78 depressed patients between 2010 and 2013 in a double-blind study. They concluded that a traditional Chinese medicine decoction used as treatment was effective in improving depression symptoms in a 6-week period and showed a few adverse effects in comparison to another traditional Chinese medicine drug. Their findings were in accordance with our results, but they used a different tool (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression) in their trial and had no follow-up measure after the end of the survey.30 The major component was not considered in this study as there was a mixture of multiple herbs, although the holistic approach could explain the result quite well. This approach is acceptable for the mode of action in our study too.

A triple-blind clinical trial was performed in our university with 43 patients receiving Cuscuta plantiflora, Nepeta menthoides, or placebo for 8 weeks in order to assess the effect of these herbal medicines as adjuvant therapy to conventional treatment in patients with major depression. Having used the same tool as the current survey, all 3 groups showed significant decrease in total Beck Depression Inventory scores at the end of the trial.11 The findings were consistent with ours: they indicated the role of herbal products suggested in traditional Persian medicine textbooks for the treatment of depression. It is of great interest that we used anise oil as independent drug, but Firoozabadi and colleagues distributed their drugs as an adjuvant to conventional treatment. The power of our study was higher simply because the number of participants in our groups was more than double in contrast to their trial. The resemblance in response against the aforementioned issues shows the priority and potency of anise oil to alleviate various symptoms of depression.

Aqueous extract of Echium amoenum (Boraginaceae), based on traditional Persian medicine beliefs, could well elate the mood. Daily consumption of 375 mg of this medicament in people with mild to moderate depression for a 6-week period showed a significant effect on depressed patients in the fourth week.31 They applied the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression tool for their assessment, but the difference in outcomes and the weak response compared to our study may arise from the limitations in the trial by Sayyah et al. Their sample size paucity and the low dose of herbal component may elucidate the dissimilarity between results. The antidepressant mechanism is currently unknown for borage32 and anise too.

Darbinyan et al evaluated standardized extract of Rhodiola rosaea radix (roseroot), SHR-5, in 89 patients with mild or moderate depression. The results revealed antidepressive potency while administered in doses of 340 or 680 mg daily.33 This effect has been attributed to inhibition of monoamine oxidase A, monoamine, and neuro-endocrine modulation.32 The findings were in accordance with our trial despite the fact that the evaluating tools, dosage amount, and duration of trials were dissimilar. This may result from innate potency in active components of herbs prescribed for psychiatric disorders since many years ago in traditional medicine modalities.

Another remedy for depression derived from traditional Persian medicine scholars’ recommendations is saffron (Crocus sativus L.),34,35 which has passed several trials successfully.36,37 Sixty milligrams of petal of saffron for 6 weeks reduced the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression scale total score in patients with mild to moderate depression in contrast to placebo group significantly.38 A trial on petal of Crocus sativus with half dose of the previous study demonstrated promising effect in treatment of patients and was as potent as fluoxetine, a standard antidepressant drug in conventional psychiatry.39 Our results are in line with trials performed on saffron; however, the mode of action is completely different. The main components of saffron including crucin, picrocrocin and safranal have shown antidepressive properties in recent clinical investigations10 notwithstanding it remaining not precisely true as for major ingredients of anise. These antidepressant effects arose from increased reuptake inhibition of monoamines and γ-aminobutyric acid agonist effects.32

The usage of herbal remedies are common for treatment of IBS in gastrointestinal literature; some of them like cumin40 and barberry41 have shown promising results while they did not display effects on depression in IBS patients. We know that drugs in antidepressant category have therapeutic effect on IBS,42 and it could be eye-catching to judge if anise could influence on the treatment of IBS too. This is obviously a theory that should be inspected in future trials.

Limitations

Although the Persian medicine sages’ recommendations focused on the effect of anise preparations for gastrointestinal problems,43 the aim of our study was not to assess the efficacy of this herb on removing the symptoms of IBS. It would be followed in another study simultaneously. We allocated patients with mild to moderate depression while those with severe symptoms where ignored in the current investigation. Longer follow-up time is a matter of concern too. The preferred dosage form in traditional Persian medicine books is decoction, but because of blinding necessities and standardization process of treatment drug, we substituted capsules. As the dosage form and route of administration is of great importance to act properly in traditional Persian medicine hakims’ comments,22 this may result in decrease in response rate.

Conclusion

Anise oil, a famous herbal remedy adopted from traditional Persian medicine textbooks, revealed a promising result in alleviating the symptoms of mild to moderate depression in patients suffering from IBS in comparison to active control and placebo groups. It is not exactly clear how anise acts as an antidepressant agent although the main ingredients are known. While the consumption of anise is recommended in removing depression symptoms in traditional Persian medicine references, further high-quality investigations are mandatory to seek the mode of action and bring about evidence for its efficacy with larger numbers of participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate Eng. Mohammad Reza Sanayeh for his contribution to the syntactical amendments and editing the article.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: MMJ introduced the concept and design for the trial, was involved in data gathering, wrote the draft, and revised the final manuscript. AMT and SA introduced the design of the trial, prepared the experimental medicaments, and revised the final manuscript. MP contributed in data analysis, wrote the draft, and revised the final manuscript. The other coauthors contributed toward the guidance, critical revision, and correction of the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the ethics committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (SUMS, CT-92-6460).

References

- 1. Keshteli AH, Dehestani B, Daghaghzadeh H, Adibi P. Epidemiological features of irritable bowel syndrome and its subtypes among Iranian adults. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28:253–258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shani-Zur D, Wolkomir K. Irritable bowel syndrome treatment: a multidisciplinary approach [in Hebrew]. Harefuah. 2015;154:52–55, 66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fukudo S, Hahm KB, Zhu Q, et al. Survey of clinical practice for irritable bowel syndrome in East Asian countries. Digestion. 2015;91:99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee YT, Hu LY, Shen CC, et al. Risk of psychiatric disorders following irritable bowel syndrome: a nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fadgyas-Stanculete M, Buga AM, Popa-Wagner A, Dumitrascu DL. The relationship between irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric disorders: from molecular changes to clinical manifestations. J Mol Psychiatry. 2014;2:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lydiard RB. Irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety, and depression: what are the links? J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 8):38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Modabbernia MJ, Mansour-Ghanaei F, Imani A, et al. Anxiety-depressive disorders among irritable bowel syndrome patients in Guilan, Iran. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saki K, Bahmani M, Rafieian-Kopaei M. The effect of most important medicinal plants on two important psychiatric disorders (anxiety and depression)—a review. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7(suppl 1):S34–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nikfarjam M, Parvin N, Assarzadegan N, Asghari S. The effects of Lavandula angustifolia Mill infusion on depression in patients using citalopram: a comparison study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15:734–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pasalar M, Choopani R, Mosaddegh M, et al. Efficacy of Jollab in the treatment of depression in dyspeptic patients: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2015;20:104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Firoozabadi A, Zarshenas MM, Salehi A, Jahanbin S, Mohagheghzadeh A. Effectiveness of Cuscuta planiflora Ten. and Nepeta menthoides Boiss. & Buhse in major depression: a triple-blind randomized controlled trial study. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2015;20:94–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karimzadeh F, Hosseini M, Mangeng D, et al. Anticonvulsant and neuroprotective effects of Pimpinella anisum in rat brain. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pasalar M, Lankarani KB. Herbal medicines, a prominent component in complementary and alternative medicine use in gastrointestinal field. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:935–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saha L. Irritable bowel syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and evidence-based medicine. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6759–6773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Randall C, Saurez A, Zaga-Galante J. Current strategies in the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Intern Med. 2014;S1:006 doi:10.4172/2165-8048.S1-006. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Black TP, Manolakis CS, Di Palma JA. “Red flag” evaluation yield in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21:153–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shafiee A, Nazari S, Jorjani S, Bahraminia E, Sadeghi-Koupaei M. Prevalence of depression in patients with beta-thalassemia as assessed by the Beck’s Depression Inventory. Hemoglobin. 2014;38:289–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories–IA and –II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67:588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ullah H, Mahmood A, Honermeier B. Essential oil and composition of anise (Pimpinella anisum L.) with varying seed rates and row spacing. Pak J Botany. 2014;46:1859–1864. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Orav A, Raal A, Arak E. Essential oil composition of Pimpinella anisum L. fruits from various European countries. Nat Prod Res. 2008;22:227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aghili Shirazi MH. Qarabadin-e Kabir [Great Pharmacopoeia]. Tehran, Iran: Institute of Medical History, Islamic Medicine and Complementary Medicine, Iran Medical University; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ibn al-Nafis A. Al-Shamel fi Sana’at al-Tibbiyah [in Arabic]. Tehran, Iran: Institute of Medical History, Islamic Medicine and Complementary Medicine, Iran Medical University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sina I. Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb [The Canon of Medicine]. Beirut, Lebanon: Alaalami Library; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Javed G, Anwar M, Siddiqui MA. Perception of psychiatric disorders in the Unani system of medicine—a review. Eur J Integr Med. 2009;1:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mosaffa-Jahromi M, Pasalar M, Afsharypuor S, et al. Preventive care for gastrointestinal disorders; role of herbal medicines in traditional persian medicine. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2015;10:e21029. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu L, Liu C, Wang Y, Wang P, Li Y, Li B. Herbal medicine for anxiety, depression and insomnia. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13:481–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Qazi N, Khan RA, Rizwani GH. Evaluation of antianxiety and antidepressant properties of Carthamus tinctorius L. (safflower) petal extract. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2015;28:991–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Herrera-Ruiz M, Garcia-Beltran Y, Mora S, et al. Antidepressant and anxiolytic effects of hydroalcoholic extract from Salvia elegans. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;107:53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Samojlik I, Mijatovic V, Petkovic S, Skrbic B, Bozin B. The influence of essential oil of aniseed (Pimpinella anisum L.) on drug effects on the central nervous system. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:1466–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yang J, Jiang L, Li Y, et al. Clinical treatment of depressive patients with anshendingzhi decoction. J Tradit Chin Med. 2014;34:652–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sayyah M, Sayyah M, Kamalinejad M. A preliminary randomized double blind clinical trial on the efficacy of aqueous extract of Echium amoenum in the treatment of mild to moderate major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30:166–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sarris J, Panossian A, Schweitzer I, Stough C, Scholey A. Herbal medicine for depression, anxiety and insomnia: a review of psychopharmacology and clinical evidence. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:841–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Darbinyan V, Aslanyan G, Amroyan E, Gabrielyan E, Malmström C, Panossian A. Clinical trial of Rhodiola rosea L. extract SHR-5 in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. Nord J Psychiatry. 2007;61:343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hosseinzadeh H, Nassiri-Asl M. Avicenna’s (Ibn Sina) the Canon of Medicine and saffron (Crocus sativus): a review. Phytother Res. 2013;27:475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Javadi B, Sahebkar A, Emami SA. A survey on saffron in major Islamic traditional medicine books. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2013;16:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Akhondzadeh S, Fallah-Pour H, Afkham K, Jamshidi AH, Khalighi-Cigaroudi F. Comparison of Crocus sativus L. and imipramine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a pilot double-blind randomized trial [ISRCTN45683816]. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2004;4:12–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Noorbala A, Akhondzadeh S, Tahmacebi-Pour N, Jamshidi A. Hydro-alcoholic extract of Crocus sativus L. versus fluoxetine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized pilot trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97:281–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moshiri E, Basti AA, Noorbala AA, Jamshidi AH, Hesameddin Abbasi S, Akhondzadeh S. Crocus sativus L.(petal) in the treatment of mild-to-moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized and placebo-controlled trial. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:607–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Akhondzadeh Basti A, Moshiri E, Noorbala AA, Jamshidi AH, Abbasi SH, Akhondzadeh S. Comparison of petal of Crocus sativus L. and fluoxetine in the treatment of depressed outpatients: a pilot double-blind randomized trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:439–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Agah S, Taleb AM, Moeini R, Gorji N, Nikbakht H. Cumin extract for symptom control in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a case series. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2013;5:217–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chen C, Tao C, Liu Z, et al. A randomized clinical trial of berberine hydrochloride in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Phytother Res. 2015;29:1822–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ruepert L, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, van der Heijden GJ, Rubin G, Muris JW. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD003460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ghoshegir SA, Mazaheri M, Ghannadi A, et al. Pimpinella anisum in the treatment of functional dyspepsia: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20:13–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]