Abstract

Child maltreatment is a major public health concern due to its impact on developmental trajectories and consequences across mental and physical health outcomes. Operationalization of child maltreatment has been complicated, as research has used simple dichotomous counts to identification of latent class profiles. This study examines a latent measurement model assessed within foster youth inclusive of indicators of maltreatment chronicity and severity across four maltreatment types: physical, sexual, and psychological abuse, and neglect. Participants were 500 foster youth with a mean age of 12.99 years (SD = 2.95 years). Youth completed survey questions through a confidential audio computer-assisted self-interview program. A two-factor model with latent constructs of chronicity and severity of maltreatment revealed excellent fit across fit indices; however, the latent constructs were correlated .972. A one-factor model also demonstrated excellent model fit to the data (χ2 (16, n = 500) =28.087, p =.031, RMSEA (0.012 – 0.062) =.039, TLI =.990, CFI =.994, SRMR =.025) with a nonsignificant chi-square difference test comparing the one- and two-factor models. Invariance tests across age, gender, and placement type also were conducted with recommendations provided. Results suggest a single-factor latent model of maltreatment severity and chronicity can be attained. Thus, the maltreatment experiences reported by foster youth, though varied and complex, were captured in a model that may prove useful in later predictions of outcome behaviors. Appropriate identification of both the chronicity and severity of maltreatment inclusive of the range of maltreatment types remains a high priority for future research.

Keywords: Confirmatory Factor Analysis, Foster youth, Maltreatment, Psychometrics

Child maltreatment is a risk factor associated with a range of negative outcomes across physical, social, and mental health domains (Cicchetti & Toth, 2005; Kaplan, Pelcovitz, & Labruna, 1999), and it remains a leading public health concern due to its financial and societal costs (Fang, Brown, Florence, & Mercy, 2012). A recent report released by the US Department of Health and Human Services (2016) revealed that approximately 3.5 million children are identified to child protective services each year as potential victims of maltreatment. Of these youth, approximately 20% were cases of substantiated child maltreatment and represent a population with high risk for adverse behavioral and emotional outcomes. The influence of exposure to maltreatment in childhood on later child development has been explored extensively in the literature, with effects related to various aspects of maltreatment, such as type (English, Upadhyaya, et al., 2005), chronicity (English, Graham, Litrownik, Everson, & Bangdiwala, 2005), severity (Litrownik et al., 2005), or age of onset (Thornberry, Ireland, & Smith, 2001).

Despite the growth of research on child maltreatment, the construct of child maltreatment remains difficult to define given that each maltreatment experience is comprised of several dimensions (e.g., severity, perpetrator type, duration), and that there is a wide range of means of assessing these experiences and their dimensions (e.g., child self-report, caregiver report, case-file review). No consistent definition of maltreatment has been established across states for either legal purposes related to removal of a child from their home or for research purposes in establishing relations between maltreatment exposure and outcomes. Thus, maltreatment is a complicated construct that can be conceptualized in a variety of ways, creating the potential for divergent research findings based on how the construct is operationalized.

Consequently, little guidance is available for ways to account for multiple dimensions of maltreatment using more comprehensive measurement, and yet advances in statistical methodologies provide new alternatives for accounting for multidimensionality in constructs that have layered features, such as the type, severity, and chronicity of maltreatment. Our goal is to improve the dimensionality of maltreatment measurement. To this end, we examine a latent measurement model of foster youth self-report of maltreatment experiences, inclusive of indicators of maltreatment chronicity and severity (English, Upadhyaya, et al., 2005) across four maltreatment types: physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological abuse, and neglect, to determine if a multidimensional construct of maltreatment can be fit to the data. If so, later outcomes predictions might be facilitated by the use of a coherent and inclusive model, and the model could be used as an example for the creation of future maltreatment measurement models.

Measurement Problems Associated with Dimensions of Maltreatment

Type of Maltreatment

Prior research has consistently indicated that the type of maltreatment experienced may have implications for outcomes (e.g., Perez & Widom, 1994; Spinnazola et al., 2014). However, research in which variables representing maltreatment type are used to predict outcomes has led to some discrepant findings (e.g., Moran, Vuchinich, & Hall, 2004; Taussig, 2002, Wall & Kohl, 2007). These discrepancies may be due in part to researchers’ use of idiosyncratic strategies of determining which type of maltreatment a child has experienced, reducing the likelihood results will generalize. To illustrate the challenges in using maltreatment type to predict outcomes, the methods and findings from studies using maltreatment type to predict adolescent substance abuse and then academic outcomes are described.

Taussig (2002) explored risk behaviors for substance use longitudinally during adolescence following physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect in a sample of youth in foster care. In a multiple regression analysis, her research indicated that a history of neglect was a significant predictor of substance use in youth, while physical abuse and sexual abuse were not (maltreatment categories not mutually exclusive). Conversely, in a community sample, Moran and colleagues (2004) found that all types of maltreatment (physical, sexual, emotional, and physical + sexual, maltreatment categories mutually exclusive) were associated with increased odds for substance use behavior in youth when compared to non-abused peers. Associations were strongest in youth who experienced both physical and sexual abuse when compared to just singular forms of abuse. Finally, research by Wall and Kohl (2007) in a nationally-representative sample of adolescents revealed that odds for substance use were lower in youth experiencing neglect than youth experiencing physical abuse. Although maltreatment types were mutually exclusive in this study, when a child experienced multiple maltreatment types, they were categorized as sexually abused if sexual abuse was their most severe abuse experience, and so on. Thus, the role of maltreatment type in predicting substance abuse in adolescents remains largely unclear. Whether or not maltreatment type is a useful predictor of substance abuse seems to depend at least in part on other dimensions of maltreatment, such as severity (Wall & Kohl, 2007) or the potential co-occurrence of other maltreatment types (Taussig, 2002).

Similarly, in work on maltreatment and academic outcomes, specifying maltreatment by type also has important implications regarding outcomes. A community-based longitudinal study evaluated the impact of childhood physical and sexual abuse (non mutually exclusive categories) on later academic outcomes (e.g., years of education completed, graduation rates) and previous childhood school performance (e.g., teacher and parent report of academic performance; Tanaka, Georgiades, Boyle, & McMillan, 2015). Physical abuse was associated with problematic childhood and later academic performances, whereas sexual abuse demonstrated no such relation (Tanaka et al., 2015). Perez and Widom (1994) found that compared to a matched control group, adults with a neglect history significantly differed on overall IQ and reading ability, with a physical abuse history significantly differed on overall IQ, and with a sexual abuse history did not differ on cognitive abilities. Lastly, another prospective, longitudinal study compared academic outcomes in a group of young adults with a neglect history to a matched control group (Nikulina, Widom, & Czaja, 2011). In a multiple regression analysis, it was determined that a history of neglect was uniquely predictive of negative academic outcomes, such as cognitive ability and number of years completed in school. However, other types of maltreatment were not included in the analyses. Similar to the substance abuse findings, the association between maltreatment type and academic outcomes seems to depend on factors such as which other maltreatment types are included, and whether maltreatment types are mutually exclusive.

Given the discrepancies in the findings reviewed above, it is unsurprising that research has identified significant overlap across maltreatment types (Herrenkohl & Herrenkohl, 2009). Use of latent profile analysis has suggested this co-occurrence of maltreatment types within child may be highly meaningful for outcomes (e.g., Pears, Kim, & Fisher, 2008). Indeed, a recent study by Spinazzola and colleagues (2014) identified that psychological maltreatment accounts for a significant proportion of the variance in mental health outcomes for youth, above and beyond effects of physical and sexual abuse and thus, should be considered along with measures of physical and sexual abuse. In sum, given the multiple dimensions of maltreatment, the frequent overlap between maltreatment types, and the varied findings regarding how maltreatment type relates to outcomes in youth, a broad, more-inclusive approach to conceptualization of maltreatment that accounts for other dimensions (such as severity and chronicity) to use when examining the path between maltreatment and outcomes is warranted (Butt et al., 2011; English, Upadhyaya, et al., 2005).

Severity of Maltreatment

While it seems intuitive that the severity of a maltreatment experience may be relevant for outcomes, the ability to classify severity of experience is confounded by a number of individual (e.g., salience and appraisal of event, age of victim) and situational characteristics (e.g., perpetrator type, type of maltreatment). One cannot simply ask a child, a case manager, or a caregiver if the child has experienced mild, moderate, or severe maltreatment, as the individual appraisal of these levels could be quite varied. Nor can one use the severity of the child’s injury or behavioral response to indicate severity of maltreatment, as children’s responses can vary greatly. Severity, then, often remains an unmeasured aspect of maltreatment. Fortunately, some models of classification of severity across maltreatment types have been created and have growing empirical support for their validity and reliability. One such example is the Maltreatment Classification System (Barnett, Manly, & Cicchetti, 1993), which was then updated with the Modified Maltreatment Classification System (MMCS, English, 1997). This classification system has been used across many studies (e.g., Bolger & Patterson, 2001; Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2001), and results indicate that severity, classified in a number of different ways, accounts for a significant portion of variance in outcomes. However, it is also important to consider severity in light of other maltreatment dimensions.

Litrownik and colleagues (2005) examined various approaches to defining maltreatment severity across types of maltreatment and within types of maltreatment. Their findings revealed that accounting for maximum severity of maltreatment experience within type of maltreatment offered the greatest predictive power for youth outcomes. A study by Clemmons et al. (2007) identified maltreatment severity as a stronger predictor than number of maltreatment types experienced for later trauma symptomology. Moreover, a study of the effects of frequency and severity of maltreatment on behavioral and emotional outcomes in foster youth revealed that only severity of maltreatment significantly predicted externalizing problem behavior and adaptive behavior (Jackson, Gabrielli, Fleming, Tunno, & Makanui, 2014). Thus, severity of maltreatment appears to be an important component of youths’ maltreatment experiences, and it has significant import for youth behavioral and emotional outcomes following maltreatment exposure. In sum, severity contributes meaningful information above and beyond what can be accounted for by other maltreatment dimensions, such as frequency (Jackson et al., 2014) and type (Litrownik et al., 2005; Clemmons et al., 2007), and at the same time, the ways severity affects outcomes is dependent upon the valence of other maltreatment dimensions.

Chronicity of Maltreatment

Recognition that the chronicity of adverse life events may be significant for youth outcomes has also garnered increasing support. Chronicity is likewise a difficult construct to operationalize due to the varied ways it can be measured and its overlap with the construct of dosage of maltreatment experience. For example, within maltreatment, chronicity could be the duration of a specific maltreatment experience, the proportion of the child’s life in which a type of maltreatment occurred, and the number of different maltreatment events experienced, to identify a few ways of defining it. There is little debate, however, that ongoing and repeated child maltreatment, as compared to the experience of a singular event, likely has greater negative impact on a child’s successful developmental progression (Egeland, Sroufe, & Erickson, 1983, Copeland, Keeler, Angold, & Costello, 2007).

Relatedly, dosing (or experiencing multiple types of maltreatment) of maltreatment experiences appears to matter across outcomes, and its impact can extend beyond the effects associated with experiencing a single maltreatment type, or the effects attributable to severity (e.g., Bolger et al., 1998, Bolger & Patterson, 2001). Flaherty and colleagues (2009) noted that exposure to five or more types of adversity (such as maltreatment experiences) in early childhood was associated with increased odds for health complaints and illness at age twelve. However, simple counts of dosing across maltreatment types do not account for other important aspects of the maltreatment experience (such as severity and chronicity). For example, against expectations, some research has shown greater negative findings for youth with neglect alone in relation to cognitive functioning when compared to youth with neglect and physical abuse exposure (O’Hara, Legano, Homel, Walker-Descartes, Rojas, & Laraque, 2015). Because other maltreatment dimensions were unexplored in this study, it remains unknown whether, for example, some youth with multiple maltreatment-type exposures had less severe or less chronic maltreatment experiences than youth with single maltreatment-type experiences.

In a study seeking to parse variance in outcomes based on different indicators of chronicity of maltreatment, the number of maltreatment incidents and a chronicity measure defined by calendar duration of maltreatment experiences accounted for the most variance across a range of outcomes (English, Graham, Litrownik, Everson, & Bangdiwala, 2005). Therefore, in construction of indicators of chronicity of abuse, both the frequency of event occurrences and the number of different instances or forms of maltreatment within a broader categorization of type of maltreatment are important to consider, along with severity and type.

Group Differences in Maltreatment Measurement

Age

Youth age at the time they report their maltreatment experiences is important to take into account when defining maltreatment exposure. Generally, children under the age of three are particularly vulnerable to child abuse and neglect as these young children have the highest rates of maltreatment compared to other age ranges (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). Abuse during early childhood may be particularly detrimental due to its impact during sensitive developmental windows (e.g., Dunn et al., 2013); however, the accuracy of reports during this critical time period is limited. While young children who come into foster care may have suffered extremely detrimental abuse, younger children may be limited in their abilities to provide an accurate report of these experiences for a few reasons. Young children may provide reports of past abuse that are inaccurate, either due to poorly developed recall strategies (Greenhoot et al., 2011) or potentially due to a lack of understanding that they had indeed been abused or maltreated. Conversely, older youth may have had more opportunity for different types of maltreatment exposures and different levels of maltreatment severity. In addition, youth may be most affected by the abuse they have experienced most recently, making their reports of psychosocial problems a reflection of current distress. Further, older youth may be better at remembering and reporting their maltreatment histories, as they could have been told information about their early childhood, and they may have better memory capabilities for more recent maltreatment. Yet, these facilitative factors for reporting by adolescents are met with issues related to the potential unreliability of their retrospective reports of abuse that occurred in early childhood (e.g., Greenhoot, 2011). A final reason why the child’s age at the time of the report is important to consider is that the definitions of what constitutes as neglect change as a child ages. For example, leaving an 8-year-old unsupervised for several hours may be inappropriate, while leaving a 16-year-old for the same amount of time may not be (Stein, Rees, Hicks, & Gorin, 2009). Thus, age is important to consider when trying to comprehensively assess maltreatment.

Gender

Prior research has identified gender differences in rates of various maltreatment types, as well as differences in the strength of associations between maltreatment and youth outcomes. Age and gender can also be interrelated regarding differences in rates of maltreatment. Based on national data, younger males (<1–5 years) were more likely to be victimized at higher rates compared to girls in the same age range. However, older females (i.e., 6–10 years and 11–17 years) demonstrated higher rates of child maltreatment compared to males in the same age range (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). Regarding type, females are more likely to experience sexual abuse than males (Hines & Finkelhor, 2007), and males are more likely to experience physical abuse than females (Thompson, Kingree, & Desai, 2004). Regarding outcomes, differences in neuroendocrine profiles were found amongst male and female 7- to 10-year-olds exposed to maltreatment, with females typically exhibiting profiles indicative of hypo-neuroendocrine response following chronic maltreatment exposure, and males exhibiting profiles indicative of hyper-neuroendocrine response (Doom, Cicchetti, Rogosh, & Dackis, 2013). In a longitudinal study of internalizing and externalizing problems in children exposed to maltreatment, Godinet, Li, and Berg (2014) found that males exhibited more internalizing and externalizing problems concurrently, while females’ problems exacerbated over time. Physical abuse, while more prevalent amongst males, may be more detrimental for women over time, as women with physical abuse histories are more likely to acquire a mental health problem in adulthood than men (Thompson, Kingree, & Desai, 2004). What remains unknown is how measurement of maltreatment may vary across male and female youth reporters.

Placement Type

Residential facility placements are typically reserved for youth with extreme behavioral issues or youth who were unable to remain safe and behaviorally controlled within a traditional foster home placement (Barth, 2002). Researchers have speculated that foster youth in residential care may have more severe abuse experiences, which may have resulted in more extreme behavioral and emotional problems (Baker, Kurland, Curtis, Alexander, & Papa-Lentini, 2007). For example, rates of child abuse and neglect are remarkably high amongst all children in residential treatment centers, with about half of children with physical abuse histories and a third with sexual abuse histories (Connor, Doerfler, Toscano, Volungis, & Steingard, 2004). In addition, residential placement may exacerbate behavioral and emotional problems. For example, some sites employ inflexible point-and-level systems that may inadvertently increase the behaviors they seek to ameliorate (e.g., Mohr, Martin, Olson, & Pumariega, 2009). While youth in foster care can transition in and out of residential facilities to more traditional foster homes, placement type remains an important factor to consider when evaluating measurement of maltreatment.

The Present Study

Variability in the strength and direction of associations between maltreatment and various outcomes may be explained, in part, by the failure of many measurement approaches to account for the complexity inherent within youths’ maltreatment experiences. For example, if two studies focused on outcomes related to physical abuse, with one study accounting for factors such as severity and co-occurrences of other of other types of abuse, and the other study ignoring these factors, results may lead to grossly different conclusions about the impact of physical abuse. In response to calls for more comprehensive measurement of maltreatment across its various dimensions (Manly, 2005), the present study seeks to test whether a coherent latent construct of maltreatment can be attained in a sample of youth in foster care while also accounting for various maltreatment dimensions and other important contextual factors. Specifically, the primary goal was to evaluate a latent measurement model of youth self-report of maltreatment, inclusive of severity and chronicity across types of maltreatment in a sample of youth in foster care. A second goal of the study was to evaluate whether the maltreatment measurement model would suffice across age groups, genders, and placement types. It was hypothesized that a two-factor latent model of severity of maltreatment and chronicity of maltreatment indicated by the various types of maltreatment (i.e., neglect and physical, sexual, and psychological abuse) would provide adequate fit to the data. Additionally, the best-fitting maltreatment model was expected to be invariant across age, gender, and foster placement type.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 500 youth between the ages of 8 and 18 years who were currently enrolled in foster care in an urban county in the Midwest. Participants were enrolled in the SPARK (Studying Pathways to Adjustment and Resilience) project, a longitudinal examination of resilience in youth exposed to child maltreatment. The gender divide of the sample was approximately equal (47% female), with an average age of 12.99 years (SD = 2.95 years). Youth were primarily Black/African American (45%), with White/Caucasian (31%) as the next most commonly endorsed race, followed by Multiracial (8%) and Other (16%). Youth either resided in a residential facility (42%) or a foster (including kinship or relative) home (58%). Of the youth in this project, 57% were reported to be currently in treatment for psychological problems.

Procedure

All youth participants were in state legal custody; the state-authorized foster care administration and district county circuit provided permission for consent to participate and a release of information for all youth within their care to participate in this study. While the state agencies are deemed the legal guardian for foster youth, and as such, are responsible for consent for research, foster youth provided informed assent and foster caregivers provided informed consent. The university institutional review board approved all study procedures. Study inclusion criteria were: 1) being age eight years or older, 2) demonstrating an IQ of 70 or above, and 3) residing in out-of-home care for at least 30 days.

For study recruitment, a list of youth enrolled in the area foster care system was provided by the state agency. Recruitment of participants involved several strategies including mailings and calls to foster families, referrals from past participants in the SPARK project, in-person recruitment at residential facilities and foster care agency events, and advertisements in foster parent newsletters and on list-servs. Interested foster youth were screened for eligibility, given a thorough explanation of the project and the participation process, and then scheduled for a data collection appointment. Through the SPARK Project, data were collected directly from youth, foster caregivers, teachers, and youth case-files; however, only youth data were used for the present study. Participants recruited for the present study beyond those surveyed through the SPARK project provided only youth questionnaire data.

Once participants completed the informed consent and assent process, study measures were administered via an Audio Computer-Assisted Self Interview (A-CASI) system. The SPARK project methodology was designed to minimize the likelihood of underreporting as much as possible by using laptop computers and the A-CASI program, which read questions and answer options to participants over headphones, to promote confidentiality. To ensure participant safety and positive research experiences, a comprehensive, three- part debriefing protocol and a follow-up phone call a day later was conducted by a graduate- level, clinical child psychology student. No participant in the SPARK project indicated stress that warranted concern for future participation in the project following completion of the survey, and previous research has demonstrated a lack of negative outcomes following research with questions of a sensitive nature (Hamby & Finkelhor, 2001). For further details on study recruitment and methods please see Jackson, Gabrielli, Tunno, and Hambrick (2012).

Measures

Demographics

Demographic (i.e., age, gender, ethnicity) and placement history of each youth participant was obtained through questions asked of the youth as well as through categorization of placement type during data collection.

Maltreatment

Child history of maltreatment was assessed via child self-report. Maltreatment questions are based on the abuse coding procedures identified by The Modified Maltreatment Classification System (English, 1997), which is a revised version of the Maltreatment Classification System (MCS; Barnett, Manly, & Cicchetti, 1993). The MCS has demonstrated reliability and validity in operationalization of maltreatment experiences (Bolger & Patterson, 2001). Further, English and colleagues (2005) and Litrownik and colleagues (2005) utilized the MMCS system to conduct a study evaluating the impact of chronicity and severity of abuse on outcomes, and both studies provided results indicating that the MMCS formulation of maltreatment was adequate in predicting emotional and behavioral outcomes in youth.

Maltreatment scores were indicated by subscales assessing four primary forms of abuse: physical abuse (e.g., “about how often did someone kick or punch you”; 18 items), psychological abuse (e.g., “about how often has anyone threatened to hurt someone very important to you”; 26 items), sexual abuse (e.g., “about how often did someone touch your private parts or bottom in some way”; 12 items), and neglect (e.g., “about how often did your parents give you enough to eat”; 22 items). If a youth responded in a way that indicated abuse had happened, they received additional questions assessing the frequency and perpetrators of the abuse. Each of the abuse items had been assigned a severity code (1 = least severe, 3 = most severe) based on prior research and expert consultation. For example, prior research suggests that an experience of having one’s life threatened (e.g., being shot at with a gun) may be more severe and have more salience for emotional or behavioral outcomes than an experience of physical harm that was not life threatening (e.g., being shoved or pushed) (Litrownik et al., 2005). The director of the SPARK project utilized her prior knowledge of research on child maltreatment, information from the MMCS coding scheme, as well as consultation with experts from the LONGSCAN project to determine how best to assign severity scores to each abuse event. Further, for each abuse item endorsed, the youth participant reported on how often the event occurred (from never to almost always), which informed the measure of chronicity. The SPARK project has utilized this approach to measurement of the maltreatment construct in a similar sample, with excellent model fit in predicting substance use outcomes (χ2 (70, n = 210) = 121.494, p < .001, RMSEA (0.041–0.077) = .059, TLI = .963, CFI = .971; XXXX, XXXX, & XXXX, 2016).

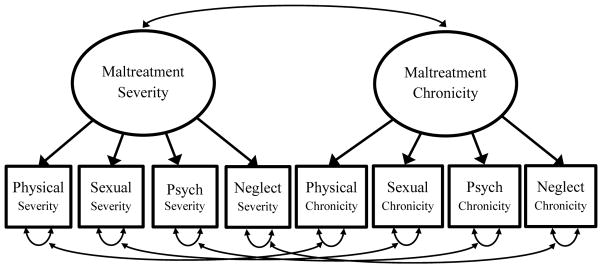

For the purposes of this research project, maltreatment was conceptualized broadly in terms of severity and chronicity, with the various types of maltreatment contributing to each of these factors (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized maltreatment measurement model with two latent constructs.

Severity of maltreatment was operationalized as an average score of the number of abuse items endorsed, weighted by their severity scores. For example, a youth endorsing two severe events (each weighted with a severity of 3) and two mild events (each weighted with a severity score of 1) received an overall severity score of 2 (i.e., 3 + 3 + 1 + 1 = 8/4 = 2). Chronicity of maltreatment was operationalized as the youth’s report of the frequency with which each individual maltreatment event occurred. This value was established through a summation of the frequency of each event. For example, a youth reporting that two events occurred “always” (frequency code of 5) and two events occurred “sometimes” (frequency code of 2) received an overall chronicity score of 14. This chronicity score therefore comprised two frequency indicators: the regularity of the maltreatment events and the number of different types of maltreatment events experienced.

Analytical Strategy

Due to the use of the A-CASI in survey administration, missing data were limited (i.e., less than 3% missing). Missingness was managed using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) algorithm available through Mplus for the structural equation model analysis. Data provided for these analyses had very little missingness with covariance coverage ranging from .907 to 1.00 with the majority of values falling above .950. Observed group differences were assessed using t-tests. Assessment of the measurement model for the maltreatment construct was conducted to demonstrate adequate fit with strong factor loadings. Confirmatory factor analyses were conducted using an SEM framework, and all factor loadings were examined to determine relative weighting and significance of influence on the latent construct. This project utilized the fixed factor method of scale setting, in which the latent variance of each latent construct is fixed to 1.0. The fixed factor method of identification creates standardized parameter estimates. Each construct had a fixed variance of four indicators; therefore the models were overidentified with more observed variance and covariance values available than the number of parameters that were estimated (Kline, 2010). Comprehensive evaluation of model fit requires use of multiple fit indices to differentiate between good or bad fit. Model fit was estimated using practical fit indices such as the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the non-normed fit or Tucker Lewis index (TLI). Acceptable levels for these fit indices is greater than 0.90 for CFI and TLI and lower than 0.08 for RMSEA (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; MacCallum et al., 1996).

Results

Within this sample, youth demonstrated a wide range of maltreatment experiences, with the majority of youth reporting multiple types of maltreatment (92%; Mean = 2.96 and SD = .95) as well as a number of different types of experiences within maltreatment type. The most common form of maltreatment reported within this sample was psychological abuse, followed by physical abuse and neglect (see Table 1). All observed indicator scores were examined across age, gender, and placement groups (see Table 2). Adolescent participants had significantly higher scores (p < .01) than child participants across all maltreatment indicators with the exception of neglect severity. Females reported higher sexual abuse severity (p = .001) and chronicity ((p < .01) and higher psychological abuse severity (p < .05) and chronicity (p < .001) than males. Youth in residential facilities had higher physical and sexual severity scores (p < .001) as well as physical and sexual chronicity scores (p = .001) than youth in foster homes.

Table 1.

Descriptive information on items endorsed and missingness across abuse type.

| Maltreatment Type | Total # of Items | % of Sample Endorsed | Mean Items Endorsed (SD) | Mean % of Items by Type Endorsed (SD) | % of Items Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | 18 | 89.7% | 4.34 (3.32) | 24.10% (18.45%) | .005% |

| Sexual | 12 | 44.9% | 1.71 (2.76) | 14.26% (22.98%) | .005% |

| Psychological | 26 | 92.3% | 6.74 (5.05) | 25.91% (19.42%) | 0% |

| Neglect | 22 | 70.2% | 3.03 (4.25) | 13.79% (19.30%) | .003% |

Table 2.

Observed mean maltreatment indicator scores by subgroup.

| Full | Child Adolescent | Female | Male | Foster | Residential | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity | |||||||

| Physicala, c | 1.32 (0.60) | 1.20 (0.67) | 1.40 (0.53) | 1.28 (0.62) | 1.36 (0.58) | 1.21 (0.65) | 1.47 (0.49) |

| Sexuala,b, c | 0.79 (1.17) | 0.52 (0.95) | 0.99 (1.27) | 0.99 (1.24) | 0.63 (1.08) | 0.62 (1.08) | 1.03 (1.24) |

| Psychologicala,b | 1.53 (0.92) | 1.38 (0.88) | 1.63 (0.94) | 1.64 (0.92) | 1.43 (0.91) | 1.47 (0.94) | 1.61 (0.89) |

| Neglect | 0.98 (0.74) | 0.97 (0.76) | 0.98 (0.73) | 0.98 (0.71) | 0.98 (0.76) | 0.94 (0.73) | 1.03 (0.75) |

| Chronicity | |||||||

| Physicala, c | 12.43 (10.78) | 10.55 (9.26) | 13.83 (11.59) | 12.49 (11.28) | 12.46 (10.40) | 11.10 (10.33) | 14.28 (11.12) |

| Sexuala,b, c | 5.36 (9.47) | 3.23 (6.96) | 6.94 (10.71) | 6.48 (10.03) | 4.39 (8.91) | 4.06 (8.43) | 7.16 (10.51) |

| Psychologicala,b | 21.97 (18.73) | 18.94 (16.38) | 24.22 (20.03) | 25.81 (19.95) | 18.67 (17.03) | 21.50 (18.69) | 22.62 (18.81) |

| Neglecta | 22.96 (16.68) | 20.11 (16.02) | 24.90 (16.87) | 23.64 (17.65) | 22.46 (15.64) | 21.98 (16.09) | 24.23 (17.37) |

Significant difference between child and adolescent groups;

Significant difference between male and female groups;

Significant difference between foster and residential groups.

All indicators in the maltreatment measurement model were significantly correlated at p < .01 level. Correlated residuals were freed based on theoretical rationale (i.e., residuals across severity and chronicity for each maltreatment type). Examination of the correlation matrix across maltreatment indicators revealed high associations across severity and chronicity within maltreatment type, which provided support for freeing of those correlated residuals (see Table 3). Residuals across each maltreatment type (e.g., physical abuse severity with physical abuse chronicity) were correlated to account for the shared error variance within type of maltreatment.

Table 3.

Correlations among indicator variables with scale means and standard deviations (SD).

| Indicator | Physical Severity | Sexual Severity | Psych Severity | Neglect Severity | Physical Chronicity | Sexual Chronicity | Psych Chronicity | Neglect Chronicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Severity | 1.000 | |||||||

| Sexual Severity | 0.266 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Psych Severity | 0.396 | 0.287 | 1.000 | |||||

| Neglect Severity | 0.151 | 0.082 | 0.162 | 1.000 | ||||

| Physical Chronicity | 0.564 | 0.362 | 0.599 | 0.235 | 1.000 | |||

| Sexual Chronicity | 0.274 | 0.865 | 0.305 | 0.078 | 0.375 | 1.000 | ||

| Psych Chronicity | 0.395 | 0.356 | 0.807 | 0.232 | 0.727 | 0.384 | 1.000 | |

| Neglect Chronicity | 0.228 | 0.118 | 0.288 | 0.587 | 0.305 | 0.134 | 0.377 | 1.000 |

All indicators significantly correlated at the p < .01 level.

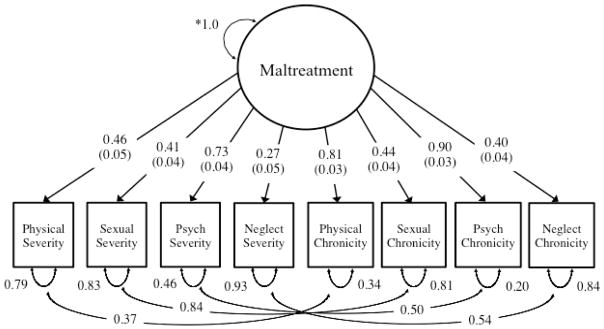

The measurement model of the maltreatment construct identified in Figure 1 demonstrated excellent fit (χ2 (15, n = 506) = 28.331, p = .020, RMSEA (0.016 – 0.065) = .042, TLI = .988, CFI = .994, SRMR = .025). However, the latent constructs of severity of maltreatment and chronicity of maltreatment were correlated at .972, suggestive of significant overlap between the constructs identified. Prior research suggests that constructs with such a high covariance may create model misfit when added to an overarching structural model due to multicollinearity. Therefore, for the present study these two latent constructs were collapsed into one overarching construct of maltreatment, indicated by both severity and chronicity scores across each abuse type. Given the nestedness of these two models, a chi-square difference test was evaluated to determine if the more complex model provided significantly better model fit. This test revealed a nonsignificant difference across models (Δχ2 (1) = 3.095, p = .079), which indicated that the more parsimonious model using just one latent construct of maltreatment was proficient in capturing the variance explained by the indicators. Thus, the final latent maltreatment model identified in Figure 2, which also demonstrated excellent fit (χ2 (16, n = 506) = 31.426, p = .012, RMSEA (0.020 – 0.066) = .044, TLI = .987, CFI = .993, SRMR = .026), was determined to be the best-fitting measurement model for the present data.

Figure 2.

Final measurement model of a single maltreatment factor with standardized loadings, standard errors, correlated residual values, and residual error values.

Factorial Invariance Tests

Age

To examine invariance across groups, the first step was to test for configural invariance. This was accomplished by testing the measurement model for child (ages 8 – 12 years) and adolescent (ages 13 – 18 years) groups separately. The maltreatment model demonstrated adequate fit in the child group (χ2(16, n = 213) = 22.915, p = .116, RMSEA (0.000–0.083) = .045, TLI = .990, CFI = .983) as well as the adolescent group (χ2(16, n = 287) = 33.459, p = 0.006, RMSEA (0.032–0.091) = .062, TLI = .977, CFI = .987). Once the overall configuration of fixed and freed parameters was deemed equivalent across groups, weak invariance tests (metric invariance) were conducted to determine if indicator factors loadings were equivalent. Loadings were fixed to be equivalent across groups, and this nested model was compared to the configural model using the RMSEA ‘Reasonableness’ Test, examination of changes in CFI values, and the Chi-Square Difference test. After factor loadings were identified as equivalent across groups, strong invariance tests (scalar invariance) were conducted to determine if intercepts were equivalent. The fit for the full scalar invariance model was significantly worse than the metric invariance model, so we explored the possibility of partial invariance. Use of model data, modification indices, and theoretical reasons led us to allow the intercepts for neglect chronicity to differ across age groups, thus allowing us to achieve partial scalar invariance across child and adolescent groups (χ2(45, n = 500) = 90.772; RMSEA(.045 – .083) = .064; CFI = .978; TLI = .972).

Gender

During configural invariance testing, the maltreatment model demonstrated adequate fit in the female group (χ2(16, n = 234) = 34.325, p = 0.005, RMSEA(0.037 – 0.102) = .070, TLI = .971, CFI = .984) as well as the male group (χ2(16, n = 266) = 20.085, p = .216, RMSEA(0.000 – 0.068) = .031, TLI = .993, CFI = .996). At the metric invariance test level loadings were fixed to be equivalent across groups, the nested model test revealed no significant decline in model fit indices. The strong invariance test revealed that the fit for the full scalar invariance model was significantly worse than the metric invariance model, and model data, modification indices, and theoretical reasons suggested that the intercepts for psychological chronicity differed across gender groups. Freeing this intercept resulted in partial scalar invariance across female and male groups (χ2(45, n = 500) = 91.143; RMSEA(.045 – .083) = .064; CFI = .978; TLI = .973).

Placement

Finally, during configural invariance testing across placement types, the maltreatment model demonstrated adequate fit in the foster home group (χ2(16, n = 289) = 31.929, p = .010, RMSEA(0.028 – 0.088) = .059, TLI = .977, CFI = .987) as well as the residential facility group (χ2(16, n = 211) = 12.175, p = .732, RMSEA(0.000 – 0.047) = .000, TLI=.999, CFI=.999). Metric invariance tests were passed, revealing no significant degradation of fit when loadings were constrained to be equal across groups. Again, full scalar invariance was not obtained, and model data, modification indices, and theoretical reasons suggested that the intercepts for psychological chronicity differed across placement groups as well. Freeing this intercept allowing us to achieve partial scalar invariance across the foster home and residential facility groups (χ2(45, n = 500) = 90.772; RMSEA(.045 – .083) = .064; CFI = .978; TLI = .972). The fact that both gender and placement had intercept differences likely relates to the fact that females in this sample were much more likely to reside in foster homes and males more likely to reside in residential facilities than expected (χ2(1, n = 500) = 23.982, p < 0.001).

Discussion

The present study is one of the first examinations of a CFA of a latent measurement model of severity and chronicity of maltreatment across physical, sexual, and psychological abuse and neglect experiences in foster youth. As such this research moves the field of study on maltreatment closer to a comprehensive approach to measurement of maltreatment experiences in youth and offers a framework for future studies to build upon when examining shared variance across maltreatment types. Based on the high number of different and co-occurring types of abuse reported by participants in the present sample as well as the varied nature of the chronicity and severity of their maltreatment experiences, measurement of their full maltreatment history clearly requires a more comprehensive approach, such as the measurement model tested in the present manuscript. Findings provide support for the feasibility of a unified maltreatment construct with good model fit identified in the present CFA, which provides support for the hypothesis posited. Based on the high correlation between the latent constructs of chronicity and severity, a one-factor measurement model was also tested, which provided excellent model fit as well. Moreover, invariance testing suggests that at least partial scalar invariance for the measurement model can be achieved across groupings by age, gender, and placement type.

Prior research has demonstrated that for youth, particularly youth in foster care, co-occurring experiences across type of maltreatment is more normative than experiences of just one type of maltreatment in isolation (Herrenkohl & Herrenkohl, 2009; Mills et al., 2013). Indeed, in the present sample the mean number of types of maltreatment endorsed across the four types assessed was approaching three with 92% endorsing more than one type of maltreatment. Therefore, simplistic categorizations of “sexually abused” or “neglected” may be insufficient in capturing the complexity of youths’ actual experiences; yet, much of the prior research on child maltreatment and outcomes in youth has focused on the effects of a single type, namely, physical or sexual abuse. Although psychological abuse and neglect may be far more difficult to measure and substantiate than more overt instances of maltreatment (e.g., physical abuse), given the strength of associations and high co-occurrence of these types of abuse with physical and sexual abuse, the current study emphasizes the importance of measuring and gathering such information.

Indeed, within the present sample, psychological maltreatment severity and psychological maltreatment chronicity provided a few of the strongest loadings in the overall measurement model. Moreover, psychological maltreatment indicators were highly correlated with other indicators in the model, and specifically with physical abuse indicators. This is a finding that has been demonstrated in prior research by Bolger and Patterson (2001), who decided to combine indicators of physical and psychological maltreatment into a unified category for their study. Given that psychological abuse experiences were some of the most commonly endorsed maltreatment experiences in this sample, consideration of the influence and co-occurrence of psychological maltreatment with other forms of abuse and neglect remains an important task for future research and should be considered in research attempting to account for the range of maltreatment experiences occurring for youth in foster care.

Chronicity of maltreatment experiences also appears to matter for explaining the variance in outcomes for youth (Hodges et al., 2013), and it is unclear what information is lost about dosage of maltreatment experiences (such as chronicity of abuse) if only the presence of one or two types of maltreatment are assessed. A child may have had one sexual abuse exposure, but years of neglect; whereas another child may have had one experience of sexual abuse but no neglect history. Furthermore, severity and chronicity of abuse likely varies across given types of maltreatment, so simple counts of number of experiences within type is insufficient. Research on outcomes following child maltreatment should account for co-occurrence across types as well as variability of chronicity within type of maltreatment, which was a method utilized in the design of the present study.

Across all maltreatment types, the severity and chronicity indicators for neglect performed the most poorly and represented the lowest correlations with other abuse types. Our interpretation of this finding is the limitations encountered in defining levels of severity and chronicity within the neglect construct. Specifically, it may be difficult for a child to quantify the lack of action from a caregiver. For example, when measuring neglect, the child was asked for how long they went without having a parent provide basic needs (e.g., being brought to the doctor when needing medical treatment) and the research team coded severity based on the MMCS coding system. Very little research is available to suggest what specific features of neglect relate to negative outcomes for youth, and even within the neglect subtype there may be overlap with other types of maltreatment. For example, unmet emotional needs likely overlaps with psychological abuse, and refusal to bring a child to a medical appointment when needed could overlap with physical abuse. The area of research on neglect subtypes and severity seems most fertile for innovative statistical approaches such as latent class analysis to assist in development of models for how to approach this construct more comprehensively.

Given the poor performance of neglect indicators in the overall measurement model, it is not surprising that freeing the intercept for neglect chronicity in invariance tests improved the overall model fit across child and adolescent group comparisons. Older youth are given more freedom and independence in their self-care, and it is developmentally appropriate for older youth to manage more of their activities of daily living (e.g., Stein et al., 2009). The issue of how best to measure neglect across age-spans remains difficult, however, due to the changing needs of the child over time. Similarly, freeing the intercepts for psychological chronicity improved model fit for tests across gender groups and placement type groups. Females reported higher levels of psychological chronicity than males, and youth in foster homes reported higher levels of psychological chronicity than youth in residential facilities. These issues may be related, as, in our sample more boys were placed in residential facilities than girls. Further examination of item-level data across these subgroups is warranted, and additional research on gender and placement differences across maltreatment types is needed.

The present findings should be considered in light of some limitations inherent within this research. First, this study was conducted in an urban region within a large-midwestern city. While the sample is representative demographically of youth in foster care in the present region and nationwide, it is unclear how results of this model may generalize to youth residing in more rural settings or other regions of the country. Second, while overall model fit indices are excellent for the maltreatment measurement model, individual indices ranged in their strength of loadings and residual variances, which may be indicative of a less reliable model overall. This new approach to operationalization of severity and chronicity across type, although it follows similar approaches used in the past, may require additional testing and replication. Further, use of child self-report may result in loss of meaningful information around early childhood maltreatment experiences or experiences that are not readily remembered or disclosed. These findings should be replicated with another sample that is recruited from multiple regions of the country to increase the generalizability of findings, and results would be further supported if models could be replicated using alternative reporters of maltreatment such as caregivers or case-file data.

Despite these limitations, however, results offer a unique perspective on how to summarize the varied and complex maltreatment experiences of youth in foster care. Morever, information from the present study provides a unique look at how different types of abuse may overlap and correlate with outcomes. Information from the present study can serve as a framework for future work to develop more comprehensive and effective ways to measure complex features of maltreatment history for youth.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Mental Health, RO1 grant MH079252-03 as well as funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), F31 grant DA034423 awarded to Joy Gabrielli. The writing of this manuscript was supported in part by Joy Gabrielli’s participation in the NIDA T32 fellowship training grant DA037202.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Drs. Gabrielli, Jackson, Tunno, and Hambrick report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barth RP. Institutions vs. foster homes: The empirical base for the second century of debate. Chapel Hill: Annie E. Casey Foundation, University of North Carolina, School of Social Work, Jordan Institute for Families; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Child abuse, child development, and social policy. Norwood: Ablex; 1993. pp. 7–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ. Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to peer rejection. Child Development. 2001;72:549–568. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ, Kupersmidt JB. Peer relationships and self-esteem among children who have been maltreated. Child Development. 1998;69:1171–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Butt S, Chou S, Browne K. A rapid systematic review on the association between childhood physical and sexual abuse and illicit drug use among males. Child Abuse Review. 2011;20:6–38. doi: 10.1002/car.1100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Child maltreatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:409–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons JC, Walsh K, DiLillo D, Messman-Moore TL. Unique and combined contributions of multiple child abuse types and abuse severity to adult trauma symptomatology. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12(2):172–181. doi: 10.1177/1077559506298248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello J. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:577–584. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Sroufe LA, Erickson MF. Developmental consequence of different patterns of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1983;7:459–469. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(83)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ the LONGSCAN Investigators. Modified Maltreatment Classification System (MMCS) 1997 Retrieved from http://www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan.

- English DJ, Graham JC, Litrownik AJ, Everson M, Bangdiwala SI. Defining maltreatment chronicity: Are there differences in child outcomes? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:575–595. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Upadhyaya MP, Litrownik AJ, Marshall JM, Runyan DK, Graham JC, Dubowitz H. Maltreatment’s wake: The relationship of maltreatment dimensions to child outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:597–619. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Brown DS, Florence CS, Mercy JA. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child abuse & neglect. 2012;36(2):156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty EG, Thompson R, Litrownik AJ, Zolotor AJ, Dubowitz H, Runyan DK, … Everson MD. Adverse childhood exposures and reported child health at age 12. Academic Pediatrics. 2009;9(3):150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby SL, Finkelhor D. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2001. Choosing and using child victimization questionnaires (NCJ186027) pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl RC, Herrenkohl TI. Assessing a child’s experience of multiple maltreatment types: Some unfinished business. Journal of Family Violence. 2009;24:485–496. doi: 10.1007/s10896-009-9247-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges M, Godbout N, Briere J, Lanktree C, Gilbert A, Kletzka NT. Cumulative trauma and symptom complexity in children: A path analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37:891–898. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Y, Gabrielli J, Fleming K, Tunno AM, Makanui PK. Untangling the relative contribution of maltreatment severity and frequency to type of behavioral outcome in foster youth. Child abuse & neglect. 2014;38(7):1147–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Y, Gabrielli J, Tunno AM, Hambrick EP. Strategies for longitudinal research with youth in foster care: A demonstration of methods, barriers, and innovations. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34:1208–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SJ, Pelcovitz D, Labruna V. Child and adolescent abuse and neglect research: A review of the past 10 years. Part I: Physical and emotional abuse and neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1214–1222. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3. New York: Guilford; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Litrownik AJ, Lau A, English DJ, Briggs E, Newton RR, Romney S, Dubowitz H. Measuring the severity of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:553–573. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–149. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT. Advances in research definitions of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(5):425–439. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children’s adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(04):759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills R, Scott J, Alati R, O’Callaghan M, Najman JM, Strathearn L. Child maltreatment and adolescent mental health problems in a large birth cohort. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37:292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran PB, Vuchinich S, Hall NK. Associations between types of maltreatment and substance use during adolescence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikulina V, Widom CS, Czaja S. The role of childhood neglect and childhood poverty in predicting mental health, academic achievement and crime in adulthood. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48:309–321. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9385-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara M, Legano L, Homel P, Walker-Descartes I, Rojas M, Laraque D. Children neglected: where cumulative risk theory fails. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;45:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Kim HK, Fisher PA. Psychosocial and cognitive functioning of children with specific profiles of maltreatment. Child abuse & neglect. 2008;32(10):958–971. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez CM, Widom CS. Childhood victimization and long-term intellectual and academic outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1994;18:617–633. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinazzola J, Hodgdon H, Liang LJ, Ford JD, Layne CM, Pynoos R, … Kisiel C. Unseen wounds: The contribution of psychological maltreatment to child and adolescent mental health and risk outcomes. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6(S1):S18–S28. doi: 10.1037/a0037766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M, Rhys G, Hicks L, Gorin S. Research Brief. Department for Children, Schools and Families; London: 2009. Neglected adolescents: Literature review. DCSF-RBX-09-04. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/research/pdf/Neglected.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Georgiades K, Boyle MH, MacMillan HL. Child maltreatment and educational attainment in young adulthood: Results from the Ontario Child Health Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015;30:195–214. doi: 10.1177/0886260514533153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taussig H. Risk behaviours in maltreated youth placed in foster care. A longitudinal study of protective and vulnerability factors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26:1179–1199. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00391-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Ireland TO, Smith CA. The importance of timing: The varying impact of childhood and adolescent maltreatment on multiple problem outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:957–979. Retrieved from http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=DPP. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonmyr L, Thornton T, Draca J, Wekerle C. A review of childhood maltreatment and adolescent substance use relationship. Current Psychiatry Reviews. 2010;6:223–234. doi: 10.2174/157340010791792581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child maltreatment 2014. 2016 Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

- Wall AE, Kohl PL. Substance use in maltreated youth: Findings from the national survey of child and adolescent well-being. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:20–30. doi: 10.1177/1077559506296316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]