Abstract

The overarching aims of this study are to (a) estimate and update knowledge on rates and predictors of awareness, perceived harmfulness, and ever use of e-cigarettes among U.S. adults and (b) to utilize that information to identify risk-factor profiles associated with ever use. Data were collected from the 2015 Health Information National Trends Survey (N=3,738). Logistic regression was used to explore relationships between sociodemographics (gender, age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, educational attainment, income, and census region), current use of other tobacco products (conventional cigarettes, cigars, and smokeless tobacco), ever use of alternative products (hookah, pipes, roll-your-own cigarettes, and snus) and e-cigarette awareness, perceived harm, and ever use. Classification and regression tree (CART) modeling was used to examine risk-factor profiles of e-cigarette ever use. Results showed that most respondents were aware of e-cigarettes (83.6%) and perceived them to be not at all or moderately harmful (54.7%). Prevalence of e-cigarette ever use was 22.4%. Current cigarette smoking and ever use of alternative tobacco products were powerful predictors of use. Other predictors of use of e-cigarettes were age, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment. Awareness and perceived harm were significant predictors among particular smoker subgroups. Fifteen risk profiles were identified across which prevalence of e-cigarette use varied from 6-94%. These results underscore the need to continue monitoring patterns of e-cigarette use. They also provide new knowledge regarding risk-profiles associated with striking differences in prevalence of e-cigarette use that have the potential to be helpful when considering the need for or impact of e-cigarette regulatory policies.

Keywords: Electronic Cigarettes, Awareness, Perceived harm, Ever Use, Prevalence, Classification and regression tree (CART)

Introduction

Electronic cigarettes, also referred to as e-cigs or vape pens, are battery-powered devices that deliver a smoke-like aerosol (i.e., vapor) that the user inhales,1 producing an experience that resembles the act of smoking a conventional cigarette.2

E-cigarettes were introduced in the U.S. market in 2007.3 Since then, their use has increased substantially.4 For example, ever use of e-cigarettes increased from 1.8% to 13.5% between 2010 and 2013.5 Prevalence of conventional cigarette smoking among U.S. adults has decreased during that same time period from 19.3% to 17.8%.6,7 These trends may indicate a shift from conventional cigarettes to other nicotine/tobacco products that are perceived as less harmful8 or potential cessation aids.9 Harm reduction advocates suggest that a switch from conventional cigarettes to e-cigarettes could produce dramatic benefits to public health, including decreased morbidity, diminished harm from second-hand exposure, and reduced smoking-related health care costs.8,10 Others caution that the growing popularity of e-cigarettes may encourage uptake of nicotine use among youth who otherwise would not have used tobacco products or otherwise undermine cessation efforts among established cigarette smokers.11-13 However, the relatively recent emergence of e-cigarettes leaves longer-term health impacts largely unknown. Given these varied potential outcomes, there is a clear need for ongoing surveillance of e-cigarette use.

The propensity to use e-cigarettes, like other nicotine/tobacco products, is influenced by multiple factors.14 Past studies have demonstrated that exposure to e-cigarette advertising and lower harm perception is associated with a higher likelihood of use.15 Certain sociodemographic characteristics such as younger age, male sex, higher educational attainment,16 and White race/ethnicity are associated with greater odds of e-cigarette use5,17 as is being a current or former cigarette smoker.18,19 Similar associations are seen with use of any nicotine or tobacco product20,21 however there is also documentation of e-cigarette use among never tobacco users.22-24 Additionally, concerns are also warranted for uptake of e-cigarettes among non-smoking young adults and adults, since these life stages typically mark the progression from tobacco initiation to regular use.25

Several population-based studies have estimated e-cigarette awareness, perceived harm, or ever use among US adults,26-28 but each has had limitations. Few studies have simultaneously explored all three factors within the same population.27 Far too little attention has been paid to the prevalence of e-cigarette use among sexual minority populations17,29,30 despite their higher rates of cigarette smoking and use of other tobacco products than heterosexual individuals.31-33 Finally, most studies exploring prevalence of e-cigarette use have focused on use as a function of cigarette smoking status.4,5,11,18,26 The increasing rates of dual use of e-cigarettes and other tobacco products17,34 and the evidence that use of e-cigarettes may be associated with increased risk of progression to cigarette smoking in never smokers,22 highlights the need of studies exploring e-cigarette use under a broader array of circumstances.

The present study aims to address these gaps in the literature. Specifically, the goals of this study were to estimate prevalence of awareness, perceived harmfulness, and ever use of e-cigarettes among US adults and to examine associations with sociodemographics and use of other tobacco and nicotine products. Additionally, we conducted a Classification and Regression Trees (CART) analysis, an innovative approach that examines how combinations of individual characteristics can be used to develop risk profiles,35-37 which to our knowledge has not yet been used to model use of e-cigarettes.

Methods

Data source

Data were collected from the most recent Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS).38 HINTS is a nationally-representative, cross-sectional survey of the U.S. non-institutionalized population commissioned by the National Cancer Institute since 2003, with the 2015 survey conducted in partnership with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The 2015 version introduced questions about new tobacco products, perceptions of tobacco product harm, and tobacco product claims. The survey used a probability sampling design to obtain a nationally representative sample of the U.S. adult population. A stratified sample of U.S. residences received the questionnaire by mail. The adult in the household who would next have a birthday was asked to complete the survey. Data was collected from May 2015 to September 2015.

Measures

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Sociodemographic information assessed included age, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, educational attainment, annual household income, and census region.

Tobacco Product Use

Cigarette smoking status, cigar smoking status, and smokeless tobacco use derived from three items assessing ever use (“Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?”, “How many cigars, cigarillos, or little filtered cigars have you smoked in your entire life?”, and “Have you used chewing tobacco, snus, snuff, or dip, at least 20 times in your entire life?”) and another three assessing current use (“Do you now smoke cigarettes every day, some days, or not at all?”, “Do you now smoke cigars, cigarillos, or little filtered cigars every day, some days or not at all?”, and “Do you now use chewing tobacco, snus, snuff, or dip every day, some days, or not at all?”).

Never cigarette smokers and never cigar smokers were defined as those who reported less than 100 cigarettes or cigars lifetime. Never smokeless tobacco users were defined as those reporting using smokeless products less than 20 times lifetime.

Former cigarette smokers or cigar smokers were defined as those who smoked at least 100 cigarettes or cigars lifetime but were currently not smoking. Former smokeless tobacco users were defined as those respondents who reported using smokeless tobacco products at least 20 times lifetime but were currently not consuming.

Current cigarette and cigar smokers were defined as those who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes or cigars lifetime and now smoking daily or some days. Current users of smokeless tobacco products were defined as those who reported using smokeless tobacco at least 20 times lifetime and now using smokeless tobacco daily or some days.39

Alternative Tobacco and Nicotine Delivery Product Use

Ever use of e-cigarettes, hookah, pipe filled with tobacco, roll-your-own cigarettes, and snus, was explored using a single item. Those who endorsed use of any of these products in response to the question: “Which of the following tobacco products have you tried?” were coded as ever users.

Awareness and Perceived Harmfulness of E-Cigarettes

Awareness and perceived harmfulness of e-cigarettes were determined using two items. The question “Which of the following have you ever heard of?” was used to assess awareness, with those who endorsed “e-cigarettes” categorized as aware of e-cigarettes. Individuals who did not endorse the “e-cigarette” alternative were categorized as unaware. Perceived harmfulness of e-cigarettes was assessed with the question: “How harmful do you think e-cigarettes are to a person's health?” and the response options were: “not at all”, “moderately harmful”, and “very harmful”.

Statistical Analyses

Sample-adjusted frequencies and their respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were generated for all variables. To identify correlates of awareness, perceived harm, and ever use of e-cigarettes, we conducted a series of steps. First, simple logistic regression was used to examine relationships between each potential predictor (sociodemographic characteristics, tobacco use status, and ever use of alternative tobacco products) and e-cigarette awareness, perceived harmfulness, and ever use. Second, one initial multivariate model for each dependent variable (awareness, perceived harmfulness, and ever use) that included only variables that were significant in the univariate analyses at 0.25 was tested. Variables that were not significant in the multivariate model at 0.05 were removed and the multivariate analysis was conducted again. Prevalence and predictors of awareness were explored among the entire sample. For perceived harmfulness and ever use of e-cigarettes, analyses were restricted to respondents who were aware of e-cigarettes. These analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Finally, a classification and regression tree (CART) analysis was conducted to identify which combinations of variables (sociodemographics, tobacco use status, ever use of alternative tobacco products, and both awareness and perceived harmfulness of e-cigarettes) led to a lower-and higher-risk of ever use of e-cigarettes (i.e., risk profiles). CART analysis is a nonparametric procedure that uses a series of binary splits to create a hierarchical decision tree based on a dependent variable (e.g., ever use of e-cigarettes), and, in the process, identifying independent variables and their interactions with the most exploratory power; thereby generating unique combinations of variables that most accurately predict low- and high-risk groups. CART starts by placing all the sample into one group (i.e., the parent node) and splitting this node into two subgroups (i.e., child nodes) as a function of the single best classifier on the dependent variable (i.e., e-cigarette ever use). Then these child nodes are recursively portioned using the Gini impurity criterion, which implies that nodes are split to produce the largest increase in homogeneity. A fully saturated tree was generated initially and then pruned by selecting the complexity parameter that minimized cross-validation error. R rpart package was used to build the tree.40

Results

Sample Characteristics

The survey sample included 3,738 respondents (Table 1). About half of respondents were ≤49 years old and female. Most respondents were White, heterosexual, had some college or higher educational attainment, had an annual household income above $50,000, and resided in the south.

Table 1.

Sample and population-weighted sociodemographic characteristics (N=3,738). Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS), United States, 2015.

| Unweighted sample size n | Weighted % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| 18-34 | 455 | 30.4 (29.8, 30.8) |

| 35-49 | 659 | 25.0 (24.5, 25.5) |

| 50-64 | 1226 | 25.6 (25.2, 25.9) |

| 65-74 | 756 | 10.8 (10.6, 10.9) |

| ≥75 | 532 | 8.2 (8.0, 8.2) |

| Gender | ||

| Women | 2018 | 50.9 (50.4, 51.3) |

| Male | 1497 | 49.1 (48.6, 49.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 2633 | 64.8 (64.0, 65.6) |

| Hispanic | 241 | 16.1 (15.6, 16.5) |

| Black/African American | 232 | 11.3 (10.6, 12.0) |

| Asian | 119 | 5.4 (4.9, 5.7) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 19 | 0.3 (0.1, 0.4) |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 6 | 0.2 (0.0, 0.3) |

| Other | 116 | 1.9 (1.6, 2.1) |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 3405 | 93.6 (91.7, 95.4) |

| Homosexual | 67 | 2.2 (1.3, 3.0) |

| Bisexual | 38 | 2.0 (1.00, 2.8) |

| Other | 57 | 2.2 (1.1, 3.2) |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 237 | 10.9 (9.5, 12.2) |

| High school | 727 | 21.0 (18.7, 23.2) |

| Vocational or Technical | 306 | 8.8 (7.0,10.5) |

| Some College | 826 | 24.0 (22.4, 25.6) |

| College graduate or more | 1578 | 35.3 (34.9, 35.5) |

| Annual household income | ||

| < 20,000 | 664 | 20.3 (17.7, 22.9) |

| 20,000-34,999 | 506 | 14.8 (12.4, 17.1) |

| 35,000-49,999 | 415 | 13.6 (11.4, 15.6) |

| 50,000-75,000 | 605 | 16.0 (14.1, 17.9) |

| ≥75,000 | 112 | 35.3 (33.1, 37.3) |

| U.S. region | ||

| Northeast | 607 | 18.0 (18.0, 18.0) |

| Midwest | 1105 | 21.2 (21.2, 21.2) |

| South | 1391 | 37.4 (37.3, 37.4) |

| West | 635 | 23.4 (23.3, 23.4) |

Note. 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

Tobacco Product Use

A total of 14.8% of respondents were current cigarette smokers, 24.9% were former smokers, and 60.3% never smoked tobacco cigarettes (Table 2). Almost 5% were current cigar smokers, 7.9% were former cigar smokers, and 87.2% never smoked cigars. Only 2.6% were current users of smokeless tobacco products, 7% were former users, and 90.4% never users.

Table 2.

Prevalence of current and ever use of nicotine and tobacco products (N=3,738). Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS), United States, 2015

| Unweighted sample size N | Weighted % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cigarette smoking status | ||

| Never smoker | 2041 | 60.3 (58.3, 62.1) |

| Former smoker | 1132 | 24.9 (23.1, 26.6) |

| Current smoker | 495 | 14.8 (12.8, 16.7) |

| Cigar smoking status | ||

| Never smoker | 3215 | 87.2 (85.1, 89.3) |

| Former smoker | 314 | 7.9 (6.2, 9.3) |

| Current smoker | 132 | 4.9 (3.5, 6.2) |

| Smokeless tobacco use | ||

| Never user | 3347 | 90.4 (88.5, 92.2) |

| Former user | 243 | 7.0 (5.5, 8.4) |

| Current user | 83 | 2.6 (1.5, 3.7) |

| Alternative tobacco products E-cigarettes | ||

| Never use | 2746 | 78.6 (75.8, 81.4) |

| Ever use | 497 | 21.4 (18.5, 24.1) |

| Hookah | ||

| Never use | 2859 | 79.9 (77.6, 82.3) |

| Ever use | 384 | 20.1 (17.6, 22.3) |

| Pipe filled with tobacco | ||

| Never use | 2619 | 82.4 (80.1, 84.7) |

| Ever use | 624 | 17.6 (15.2, 19.8) |

| Roll-your-own cigarettes | ||

| Never use | 2486 | 75.1 (72.9, 77.2) |

| Ever use | 757 | 24.9 (22.7, 27.0) |

| Snus | ||

| Never use | 3053 | 90.1 (88.2, 92.0) |

| Ever use | 190 | 9.9 (7.9, 11.7) |

Note. 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

Ever Use of Other Tobacco Products

About one-quarter (24.9%) of respondents reported having used roll-your-own cigarettes, 21.4% had used e-cigarettes, 20.1% had tried hookah, 17.6% had used a pipe filled with tobacco, and 9.9% indicated having tried snus (Table 2).

Awareness of E-cigarettes

About 83.6% of adults were aware of e-cigarettes (Table 3). Awareness was higher among adults aged 18-34, males, Whites, participants with some college, individuals with household incomes above $75,000, and those living in the Midwest. E-cigarette awareness was also higher among ever users of alternative tobacco products, former smokeless tobacco users, and current cigarette or cigar smokers.

Table 3.

Electronic cigarette awareness, perceived harm, and ever use among U.S. adults by demographics, cigarette smoking status, cigar smoking status, smokeless tobacco products use, and ever use of hookah, pipe filled with tobacco, roll-your-own cigarettes, and snus. Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS), United States, 2015.

| Characteristic | Awareness of e-cigarettesa Weighted % (95% CI) | Believe e-cigarettes are not at all or moderately harmful b Weighted % (95% CI) | Ever use of e-cigarettesb Weighted % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 83.6 (81.3, 86.0) | 54.7 (51.1, 58.3) | 22.4 (19.5, 25.3) |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18-34 | 90.0 (85.6, 94.4) | 56.2 (47.9, 64.4) | 37.4 (29.2, 45.6) |

| 35-49 | 83.5 (77.4, 89.7) | 57.6 (50.7, 64.5) | 21.1 (16.2, 26.0) |

| 50-64 | 84.6 (80.7, 88.5) | 53.3 (48.4, 58.2) | 14.8 (11.9, 17.8) |

| 65-74 | 80.4 (75.9, 85.0) | 55.4 (50.0, 60.7) | 10.0 (6.2, 18.8) |

| ≥75 | 58.5 (52.5, 64.6) | 42.9 (33.6, 52.3) | 5.7 (1.5, 9.9) |

| Gender | |||

| Women | 82.1(79.1, 85.1) | 51.1 (47.8, 54.7) | 20.6 (16.9, 24.2) |

| Male | 85.9 (82.4, 89.5) | 59.3 (53.9, 64.6) | 24.2 (19.6, 28.8) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 90.1 (88.3, 91.9) | 56.5 (53.2, 59.8) | 24.7 (21.1, 28.3) |

| Hispanic | 78.2 (70.4, 86.0) | 48.9 (34.4, 63.5) | 22.6 (13.0, 32.3) |

| Black/African American | 77.5 (69.5, 85.4) | 54.9 (41.2, 68.6) | 16.1 (5.1, 27.1) |

| Asian | 69.2 (54.8, 83.6) | 41.7 (27.5, 55.9) | 4.4 (0.0, 11.1) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 84.4 (55.6, 100) | 55.7 (15.0, 96.5) | 38.9 (0.00, 85.5) |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 61.3 (0.0, 100) | 66.7 (0.00, 100) | 0 (0.00, 0.00) |

| Other | 91.6 (83.6, 99.6) | 56.4 (41.6, 71.1) | 27.8 (13.1, 42.6) |

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Heterosexual | 84.9 (82.9, 86.8) | 54.4 (50.7, 58.1) | 21.7 (18.7, 24.7) |

| Homosexual | 94.0 (88.1, 99.9) | 51.7 (28.2, 75.3) | 20.3 (0.0, 41.0) |

| Bisexual | 96.7 (90.4, 100) | 63.1 (25.9, 100) | 60.0 (32.2, 87.8) |

| Other | 47.3 (24.9, 69.7) | 79.0 (65.1, 92.8) | 19.8 (1.9, 37.6) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 69.8 (60.2, 79.4) | 57.7 (39.4, 76.0) | 25.5 (17.9, 36.2) |

| High school | 73.8 (64.6, 82.9) | 58.1 (50.1,66.2) | 27.9 (21.1, 34.9) |

| Vocational or Technical | 88.5 (82.6, 94.3) | 53.9 (40.7, 67.1) | 25.3 (15.4, 35.3) |

| Some College | 91.2 (88.8, 93.6) | 54.9 (47.8, 62.0) | 31.1 (23.9, 38.4) |

| College graduate or more | 87.4 (85.0, 89.8) | 52.4 (48.4, 56.5) | 12.3 (8.7, 15.8) |

| Annual household income | |||

| < 20,000 | 71.4 (63.2, 79.6) | 59.0 (47.8, 70.2) | 29.2 (21.0, 37.4) |

| 20,000-34,999 | 75.2 (65.6, 84.9) | 49.1 (40.9, 57.3) | 26.1 (18.6, 33.7) |

| 35,000-49,999 | 89.6 (85.2, 93.9) | 58.7 (48.6, 68.9) | 28.9 (18.8, 38.9) |

| 50,000-74,999 | 87.9 (84.0, 91.8) | 50.9 (44.0, 57.8) | 19.9 (13.4, 26.6) |

| ≥75,000 | 92.2 (90.1, 94.4) | 55.6 (50.8, 60.3) | 18.9 (13.7, 24.3) |

| U.S. region | |||

| Northeast | 86.1 (82.3, 89.7) | 56.6 (48.6, 64.7) | 19.5 (12.7, 26.3) |

| Midwest | 87.2 (83.9, 90.5) | 60.4 (54.6, 66.3) | 26.1 (20.8, 31.4) |

| South | 82.1 (78.7, 85.5) | 56.2 (50.1, 62.2) | 20.1 (15.3, 24.8) |

| West | 81.0 (75.3, 86.8) | 45.2 (37.8, 52.5) | 24.8 (18.1, 31.6) |

| Cigarette smoking status | |||

| Never smoker | 80.1 (76.5, 83.8) | 50.5 (45.9, 55.0) | 8.3 (5.0, 11.5) |

| Former smoker | 88.4 (86.1, 90.6) | 55.2 (48.8, 61.5) | 24.1 (18.7, 29.5) |

| Current smoker | 91.1 (87.9, 94.3) | 69.1 (60.2, 78.0) | 69.7 (63.1, 76.4) |

| Cigar smoking status | |||

| Never smoker | 83.3 (80.7, 85.9) | 53.2 (49.4, 56.9) | 19.0 (16.1, 21.9) |

| Former smoker | 88.4 (82.9, 93.8) | 55.0 (43.4, 66.6) | 38.9 (27.4, 50.3) |

| Current smoker | 88.9 (81.5, 96.4) | 77.5 (61.4, 93.7) | 51.2 (34.2, 68.1) |

| Smokeless tobacco use | |||

| Never user | 82.9 (80.4, 85.4) | 53.1 (49.3, 57.0) | 18.7 (16.1, 21.3) |

| Former user | 93.3 (90.3, 96.3) | 70.1 (60.5, 79.3) | 48.8 (35.6, 61.9) |

| Current user | 85.4 (72.5, 98.3) | 64.3 (37.2, 91.5) | 57.4 (36.7, 78.0) |

| Alternative tobacco products Hookah | |||

| Never use | 93.5 (62.4, 94.7) | 53.5 (49.9, 57.1) | 13.8 (11.4, 16.4) |

| Ever use | 95.9 (93.5, 98.5) | 58.5 (49.7, 67.4) | 55.3 (47.3, 63.2) |

| Pipe filled with tobacco | |||

| Never use | 93.7 (92.6, 94.7) | 52.3 (48.4, 56.3) | 18.4 (15.4, 21.3) |

| Ever use | 95.6 (93.5, 97.7) | 64.6 (56.7, 72.5) | 40.7 (32.8, 48.5) |

| Roll-your-own cigarettes | |||

| Never use | 93.7 (92.5, 94.9) | 51.4 (47.5, 55.3) | 12.7 (9.8, 15.6) |

| Ever use | 95.0 (93.2, 96.9) | 63.9 (57.5, 70.4) | 51.1 (43.9, 58.2) |

| Snus | |||

| Never use | 93.9 (92.9, 94.8) | 53.2 (49.7, 56.7) | 16.7 (14.2, 19.3) |

| Ever use | 95.5 (92.1, 98.9) | 66.8 (55.2, 78.3) | 72.7 (64.5, 80.8) |

Note. 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

All sample (N=3,738)

Only respondents who were aware of e-cigarettes (N=3,048)

Table 4 shows results of multiple logistic regression analyses for awareness of e-cigarettes. Adults aged 18-34 and Whites had higher odds of awareness of e-cigarettes relative adults aged ≥75 years and Blacks/African Americans (20.3 (95% CI: 9.8, 41.8) and 3.1 (95% CI: 1.9, 5.0) times, respectively). Respondents with household incomes ≥$35,000 had 2.8 (95% CI: 1.3, 6.0) greater odds of being aware of e-cigarettes than those with incomes below $20,000. Compared to never smokers, current smokers and former smokers had respectively 3.0 (95% CI: 1.5, 5.8) and 2.1 (95% CI: 1.3, 3.4) times greater odds of being aware of e-cigarettes.

Table 4.

Final models, adjusted odds ratios, and 95% confidence intervals predicting awareness, perceived harmfulness and ever use of e-cigarettes. Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS), United States, 2015.

| Characteristic | Awareness a | Believe e-cigarettes are not at all or moderately harmfulb | Ever use of e-cigarettes b |

|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18-34 | 20.3 (9.8, 41.8) | 9.4 (3.5, 25.3) | |

| 35-49 | 4.5 (2.2, 9.2) | 3.9 (1.4, 10.4) | |

| 50-64 | 4.6 (2.8, 7.3) | 2.0 (0.8, 5.0) | |

| 65-74 | 3.7 (2.2, 6.4) | 1.2 (0.4, 3.2) | |

| ≥75 | 1 | 1 | |

| Gender | |||

| Women | 1 | ||

| Male | 1.3 (1.1, 1.7) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 3.1 (1.9, 5.0) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.9 (0.4, 2.2) | ||

| Black/African American | 1 | ||

| Asian | 0.4 (0.1, 1.0) | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.1 (0.0, 71.7) | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 0.7 (0.0, 14.8) | ||

| Other | 2.8 (0.7, 11.0) | ||

| Annual household income | |||

| < 20,000 | 1 | ||

| 20,000-34,999 | 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) | ||

| 35,000-49,999 | 2.8 (1.3, 6.0) | ||

| 50,000-74,999 | 2.7 (1.3, 5.3) | ||

| ≥75,000 | 4.6 (2.4, 9.0) | ||

| U.S. region | |||

| Northeast | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) | 1.6 (0.9, 3.0) | |

| Midwest | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.6) | |

| South | 1 | 1 | |

| West | 0.6 (0.4, 1.0) | 2.6 (1.5, 4.7) | |

| Cigarette smoking status | |||

| Never smoker | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Former smoker | 2.1 (1.3, 3.4) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | 4.3 (2.2, 8.5) |

| Current smoker | 3.0 (1.5, 5.8) | 2.0 (1.3, 3.3) | 35.5 (16.8, 74.8) |

| Alternative tobacco products Hookah | |||

| Never use | 1 | ||

| Ever use | 4.0 (2.3, 6.9) | ||

| Roll-your-own cigarettes | |||

| Never use | 1 | ||

| Ever use | 2.2 (1.2, 4.0) | ||

| Snus | |||

| Never use | 1 | ||

| Ever use | 3.4 (1.8, 6.3) |

Note. AOR: adjusted odd ratios; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

All sample (N=3,748)

Only respondents who were aware of e-cigarettes (N=3,048).

Perceptions of E-cigarette Harmfulness

Among respondents aware of e-cigarettes, 54.7% perceived them as not at all or moderately harmful (Table 3). A lower perception of harm was observed among adults aged ≤49, men, individuals with incomes below $20,000, and respondents living in the Midwest. Current cigar smokers, former users of smokeless tobacco, current cigarette smokers, and ever users of hookah, pipe filled with tobacco, roll-your-own cigarettes, and snus also perceived e-cigarettes as less harmful.

Table 4 shows the results of the final multiple logistic regression model for to perceived harmfulness of e-cigarettes. Men had 1.3 (95% CI: 1.1, 1.7) greater odds than women and current cigarette smokers 2.0 (95% CI: 1.3, 3.3) greater odds than never smokers of perceiving e-cigarettes as less harmful.

Ever Use of E-cigarettes

Among participants who were aware of e-cigarettes, 22.4% had used them at least once (Table 3). Higher rates of ever use were found among younger adults (18-34), males, Whites, respondents with some college, individuals with incomes below $20,000, and respondents living in the Midwest. Ever use of e-cigarettes was also highest among current users of cigarettes, cigars or smokeless tobacco and among ever users of snus, hookah, and roll-your-own cigarettes.

Table 4 shows the final multiple logistic regression model for ever use of e-cigarettes. Adults aged 18-34 and 35-49 had respectively 9.4 (95% CI: 3.5, 25.3) and 3.9 (95% CI: 1.4, 10.4) times greater odds of having tried e-cigarettes when compared with adults aged ≥75. Residents in the West or Midwest had 2.6 (95% CI: 1.5, 4.7) and 1.6 (95% CI: 1.0, 2.6) greater odds of having tried e-cigarettes than those residing in the South. Odds of having tried e-cigarettes were 35.5 (95% CI: 16.8, 74.8) times greater for current smokers and 4.3 (95% CI: 2.2, 8.5) times greater for former smokers compared to never smokers. Ever users of hookah, snus, and roll-your-own cigarettes had greater odds of having used e-cigarettes relative to never users of these products (4.0 (95% CI: 2.3, 6.9), 3.4 (95% CI: 1.8, 6.3), and 2.2 (95% CI: 1.2, 4.0), respectively).

Classification and Regression Tree (CART) Analysis

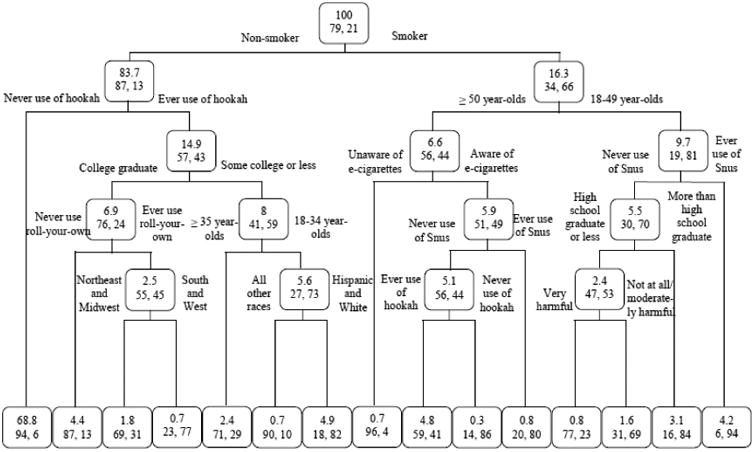

The CART analysis (Figure 1) utilized the entire sample and identified current cigarette smoking status as the strongest predictor of ever use of e-cigarettes, followed in order of strength by ever use of hookah, age, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, ever use of snus, ever use of roll-your-own cigarettes, annual household income, e-cigarette awareness, census region, cigar smoking status, perceived harm of e-cigarettes, smokeless tobacco use, and ever use of pipe filled with tobacco.

Figure 1.

A pruned, weighted classification and regression tree (CART) model of associations between ever use of e-cigarettes and the following risk factors in the U.S. adult population: cigarette smoking status, ever use of hookah, age, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, ever use of snus, ever use of roll-your-own cigarettes, annual household income, awareness of e-cigarettes, census region, cigar smoking status, perceived harm of e-cigarettes, smokeless tobacco use, and ever use of pipe filled with tobacco. Squares (nodes) represent rates of ever use of e-cigarettes among for the entire population (top-most node) or population subgroups (all other nodes). Nodes also list the proportion of the adult population represented. Using the parent node (top-most node) as an example, 79% of the population had never used e-cigarettes and 21% had used them at least once, and this node represent 100% of the US non-institutionalized adult population. Lines bellow the nodes represent the binary “yes”-“no” branching around a particular risk factor and risk factor levels, with subgroups in whom the risk factor/level is absent moving leftward and downward and those whom it is present moving rightward and downward for further potential partitioning. The bottom row comprises terminal nodes (i.e., final partitioning for a particular subgroup).

The node at the top of the figure 1 (i.e., parent node) represents 100% of the U.S. adult population of which 79% of adults had never used e-cigarettes and 21% had used them at least once. The first branching was based on current cigarette smoking status, which split the population into non-cigarette smokers (83.7%) and current cigarette smokers (16.3%) where the prevalence of ever use of e-cigarettes was 13% and 66%, respectively.

The second branching among non-cigarette smokers was based on ever use of hookah. Those who had never smoked cigarettes nor used hookah branched leftward and downward to a terminal node that represented 68.8% of the population where prevalence of ever use of e-cigarettes was 6%. Those never cigarette smokers who tried hookah branched rightward and downward to a node based on whether someone was a college graduate where ever use of e-cigarettes was much higher, 43%.

The second branching among current cigarette smokers was based on age, dividing the population into ≥50 versus 18-49 years of age. Those ≥50 years branched leftward and downward to a child node split by awareness of e-cigarettes where ever e-cigarette use was 44%. The subgroup aged 18-49 years branched rightward and downward to another child node that represented ever use of snus where the prevalence of ever use of e-cigarettes was 81%.

This branching process was repeated until the sample was classified into 15 risk profiles (Figure 1, bottom row). Current cigarette smokers, ≥50 years and unaware of e-cigarettes had the lowest ever use of e-cigarettes (4%). The highest ever use of e-cigarettes (94%) corresponded to a terminal node of current cigarette smokers, ages 18-49, who have tried snus. However, these two final nodes corresponded respectively to only 0.7% and 4.2% of the entire U.S. adult population. Balancing likelihood of use of e-cigarettes against percentage of population represented, the lowest risk profile (6%) that represented the largest proportion of the population (68.8%) corresponded to individuals not currently smoking cigarettes who never tried hookah. Looking at terminal nodes that had high-risk profiles and represented the largest percentage of the U.S. population, we noted 6 nodes with high risk of ever use of e-cigarettes (≥77%). They represented proportions of the sample ranging from 0.7 to 4.8%. These 6 high-risk terminal nodes had in common (a) current cigarette smoking and (b) ever use of alternative tobacco products including hookah, roll-your-own cigarettes, or snus as risk factors. Younger age, higher educational attainment, and being White or Hispanic were also powerful predictors that characterized two high-risk profiles (≥82%) representing 7.9% of the population (7th and 14th counting from left to right). It is noteworthy that awareness and perceived harmfulness of e-cigarettes could act as strong predictors of ever use of e-cigarettes but only within small subgroups. Specifically, ever use of e-cigarettes varied from 4% to 49% among current cigarette smokers aged ≥50 years old dependent on being aware or unaware of e-cigarettes, respectively, and from 23% to 69% among current cigarette smokers, aged 18-49 years old, who never tried snus, and had a high school education or less corresponding to perceiving e-cigarettes as very or not at all harmful, respectively.

Discussion

The aims of this study were two-fold: (1) to estimate and update knowledge on rates and predictors of awareness, perceived harmfulness, and ever use of e-cigarettes, and (2) to identify subgroups of the U.S. population that are at increased risk for ever use of e-cigarettes. Three major findings appear to have the most important implications for tobacco regulatory science: (1) the US adult population has high rates of both awareness and ever use of e-cigarettes, with most adults perceiving e-cigarettes as a reduced harm product; (2) current cigarette smoking is the strongest predictor of ever use of e-cigarettes followed by ever use of hookah and snus; and (3) sociodemographic characteristics including age, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment, as well as awareness and perceived harmfulness are independent robust predictors of ever use of e-cigarettes

To our knowledge, this study represents the latest update on e-cigarette awareness, perceived harmfulness, and ever use among the US adult population. Our results indicate that the majority of the US adult population (83.6%) is aware of the existence of e-cigarettes. Among those who were aware, more than half (54.7%) perceived e-cigarettes to be not at all or moderately harmful and nearly a quarter (22.4%) have tried them at least once. This study represents a snapshot in time thus, researchers must continue to monitor changes in awareness, harm perception, and use of e-cigarettes.

A novel approach of the current study was the use of CART analysis to quantify which variables and combinations of variables are the most important in predicting ever use of e-cigarettes. Our findings highlight information that may help explain noteworthy differences in ever use of e-cigarettes across population subgroups. First, current cigarette smoking status is the strongest predictor of ever use of e-cigarettes followed by ever use of hookah, and ever use of snus. Combination of these tobacco-use factors characterize the profiles associated with the highest and lowest prevalence of ever use of e-cigarettes. Current cigarette smokers aged 18-49 years who had tried snus represents the subgroup with the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use (94%). Conversely, non-cigarette smokers who have never tried hookah have the lowest prevalence of ever use of e-cigarettes (6%). These findings are consistent with prior studies and further confirms that users of other nicotine/tobacco products are more likely to use e-cigarettes.17,41 These patterns of ever use of multiple tobacco products merit further comments. As noted above, it is possible that smokers who have used e-cigarettes as well as other nicotine or tobacco products may seek to sustain nicotine administration using less harmful products.8 However, it is also possible that current cigarette smokers are combining use of multiple nicotine and tobacco products.34 A novel finding that should also receive considerable attention among policy makers is that having tried hookah is associated with a 7-fold increase in the prevalence of ever use of e-cigarettes among non-cigarette smokers. The reasons for this association are unclear, however these products do share certain characteristics. Both e-cigarettes and hookah are available in flavors (e.g., candy) that are more appealing to non-smokers and both are commonly used in places to socialize.17 The major concern that arises from this association is that certain subgroups of the population who do not smoke may progress in sequential stages of usage of nicotine and tobacco products beginning with less harmful products (e.g., e-cigarettes) leading to the use of more harmful products (i.e., conventional cigarettes).22

Second, the CART analysis also demonstrates certain sociodemographic characteristics and both awareness and perceived harmfulness are robust predictors of ever use of e-cigarettes. Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, we found that younger age, race/ethnic majorities, and higher education attainment are risk factors for ever use of e-cigarettes and combinations of these factors led two high-risk profiles (7th and 14th terminal nodes counting from left to right). This finding may relate to younger people and more socially advantaged individuals being more inclined to experiment with novel products with technological features.16,42 In the CART analysis, we also observed sizeable increases in ever use in association with awareness and perceived harm of e-cigarettes, but those associations were restricted to particular subsets of the population. We observed that being aware of e-cigarettes predicts ever use only among older adults. Most young adults are aware of e-cigarettes, thus it is not as distinctive a factor among them. Perceived harmfulness, can be strongly predictive among younger smokers who never tried snus and are less educated. Individuals with lower levels of educational attainment have relatively less information about health matters 43 which may make them more vulnerable to low harm-related messages regarding e-cigarettes. These results could be helpful to policy makers interested in targeting information on e-cigarettes to population subgroups most in need of additional information.

This study has several limitations that merit mention. First, the HINTS-FDA is a cross-sectional survey, which precludes causal inferences. Second, information was self-reported allowing for the potential for social desirability and recall biases. Third, the subgroups identifying themselves as sexual minorities were extremely small potentially impeding finding significant associations between sexual orientation status and dependent measures. Finally, data were only available on ever use of alternative tobacco products, not current use, which limits the possibility to monitor patterns of use over time in future investigations. Given that the rates of experimentation and regular use of alternative tobacco products are evolving rapidly, it is imperative that future iterations of this survey assess these two patterns of use. Despite these limitations, this study contributes new knowledge on e-cigarette awareness, beliefs about harm, and ever use, identifying the most important factors for ever use of e-cigarettes, and particular sub-group profiles associated with e-cigarette use. Such U.S. population-level data has the potential to be helpful to policy makers charged with developing regulatory policies on e-cigarettes.

Highlights.

Prevalence of awareness, perceived harmfulness, and ever use of e-cigarettes.

Study of risk factors for ever use of e-cigarettes in U.S. adults.

High rates of awareness and ever use of e-cigarettes were found.

Most adults perceived e-cigarettes as a reduced harm product.

Current cigarette smoking was the strongest predictor of ever use of e-cigarettes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was supported by Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science award P50DA036114 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Center of Biomedical Research Excellence award P20GM103644 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA, FDA, or NIGMS.

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to declare other than the federal research support acknowledged above.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes a Scientific Review. Circulation. 2014;129(19):1972–1986. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.007667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adkison SE, O'Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, Hyland A, Borland R, Yong HH. Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems International Tobacco Control Four-Country Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(3):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noel JK, Rees VW, Connolly GN. Electronic Cigarettes: A New ‘tobacco’ Industry? Tob Control. 2011;20(1):81. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.038562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King BA, Patel R, Nguyen KH, Dube SR. Trends in Awareness and Use of Electronic Cigarettes Among U.S. Adults, 2010–2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):219–217. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMillen RC, Gottlieb MA, Shaefer RMW, Winickoff JP, Klein JD. Trends in Electronic Cigarette Use Among U.S. Adults: Use is Increasing in Both Smokers and Nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(10):1195–1202. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamal A, Agaku IT, O'Connor E, King BA, Kenemer JB, Neff LJ. Current cigarette smoking among adults-United States, 2005-2013. [Accessed July 1, 2017];MWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014 63(47):1108–1112. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6347a4.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Current cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2011. [Accessed July 1, 2017];MWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012 61(44):889–894. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6144a2.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benowitz NL, Donny EC, Hatsukami DK. Reduced nicotine content cigarettes, e-cigarettes and the cigarette end game. Addiction. 2017;112(1):6–7. doi: 10.1111/add.13534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalkhoran S, Grana RA, Neilands TB, Ling PM. Dual use of smokeless tobacco or e-cigarettes with cigarettes and cessation. Am J Health Behav. 2015;39(2):277–284. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.39.2.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagerström KO, Bridgman K. Tobacco harm reduction: The need for new products that can compete with cigarettes. Addict Behav. 2014;39(3):507–511. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Steinberg MB, et al. Patterns of Electronic Cigarette Use Among Adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):715–719. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA. 2015;314(7):700–707. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vickerman KA, Carpenter KM, Altman T, Nash CM, Zbikowski SM. Use of Electronic Cigarettes Among State Tobacco Cessation Quitline Callers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(10):1787–1791. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatsukami DK, Biener L, Leischow SJ, Zeller MR. Tobacco and nicotine product testing. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(1):7–17. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi K, Forster JL. Beliefs and Experimentation with Electronic Cigarettes: A Prospective Analysis Among Young Adults. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(2):175–178. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartwell G, Thomas S, Egan M, Gilmore A, Petticrew M. E-cigarettes and equity: a systematic review of differences in awareness and use between sociodemographic groups. Tob Control. 2016;0:1–7. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weaver SR, Majeed BA, Pechacek TF, Nyman AL, Gregory KR, Eriksen MP. Use of electronic nicotine delivery systems and other tobacco products among USA adults, 2014: results from a national survey. Int J Public Health. 2016;61(2):177–188. doi: 10.1007/s00038-015-0761-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson FA, Wang Y. Recent Findings on the Prevalence of E-Cigarette Use Among Adults in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2016;52(3):385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popova L, Ling PM. Alternative Tobacco Product Use and Smoking Cessation: A National Study. Am J of Public Health. 2013;103(5):923–930. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Regan AK, Promoff G, Dube SR, Arrazola R. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: adult use and awareness of the ‘e-cigarette’ in the USA. Tob Control. 2013;22(1):19–23. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salloum RG, Thrasher JF, Getz KR, Barnett TE, Asfar T, Maziak W. Patterns of Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking Among U.S. Young Adults, 2013–2014. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(4):507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spindle TR, Hiler MM, Cooke ME, Eissenberg T, Kendler KS, Dick DM. Electronic cigarette use and uptake of cigarette smoking: A longitudinal examination of U.S. college students. Addic Behav. 2017;67:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Unger JB, Soto DW, Leventhal A. E-cigarette use and subsequent cigarette and marijuana use among Hispanic young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;163(1):261–264. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chivers LL, Hand DJ, Priest JS, Higgins ST. E-cigarette use among women of reproductive age: Impulsivity, cigarette smoking status, and other risk factors. Prev Med. 2016;92:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rath JM, Villanti AC, Abrams DB, Vallone DM. Patterns of tobacco use and dual use in US young adults: the missing link between youth prevention and adult cessation. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/679134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huerta TR, Walker DM, Mullen D, Johnson TJ, Ford EW. Trends in E-Cigarette Awareness and Perceived Harmfulness in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(3):339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearson JL, Richardson A, Niaura RS, Vallone DM, Abrams DB. E-cigarette awareness, use, and harm perceptions in US adults. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1758–1766. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan ASL, Bigman CA. E-Cigarette Awareness and Perceived Harmfulness: Prevalence and Associations with Smoking Cessation Outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(2):141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson SE, Holder-Hayes E, Tessman GK, King BA, Alexander T, Zhao X. Tobacco Product Use Among Sexual Minority Adults: Findings From the 2012–2013 National Adult Tobacco Survey. American journal of preventive medicine. 2016;50(4):e91–e100. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang J, Kim Y, Vera L, Emery SL. Electronic Cigarettes Among Priority Populations: Role of Smoking Cessation and Tobacco Control Policies. American J Prev Med. 2016;50(2):199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rath JM, Villanti AC, Rubenstein RA, Vallone DM. Tobacco use by sexual identity among young adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(11):1822–1831. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King BA, Dube SR, Tynan MA. Current Tobacco Use Among Adults in the United States: Findings From the National Adult Tobacco Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(11):e93–e100. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JGL, Griffin GK, Melvin CL. Tobacco use among sexual minorities in the USA, 1987 to May 2007: a systematic review. Tob Control. 2009;18(4):275–282. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.028241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, Kim AE. Multiple tobacco product use among adults in the United States: Cigarettes, cigars, electronic cigarettes, hookah, smokeless tobacco, and snus. Prev Med. 2014;62:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breiman L, Friedman JH, Olshen RA, Stone CJ. Classification and Regression Trees. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins ST, Kurti AN, Redner R, et al. Co-occurring risk factors for current cigarette smoking in a U.S. nationally representative sample. Prev Med. 2016;92:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niaura R, Chander G, Hutton H, Stanton CA. Interventions to address chronic disease and HIV: strategies to promote smoking cessation among HIV-infected individuals. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2012;9(4):375–384. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0138-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Cancer Institute. Health Information National Trends Survey 4 (HINTS-FDA) [Accessed November 11, 2016]; https://hints.cancer.gov/errors.aspx?aspxerrorpath=/&prev=search. Updated June 21, 2016.

- 39.Donaldson EA, Hoffman AC, Zandberg I, Blake KD. Media exposure and tobacco product addiction beliefs: Findings from the 2015 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS-FDA 2015) Addic Behav. 2017;72:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giovenco DP, Lewis MJ, Delnevo CD. Factors Associated with E-Cigarette Use: A National Population Survey of Current and Former Smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(4):476–480. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee HY, Lin HC, Seo DC, Lohrmann DK. Determinants associated with E-cigarette adoption and use intention among college students. Addic Behav. 2017;65:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Heide I, Wang J, Droomers M, Spreeuwenberg P, Rademakers J, Uiters E. The relationship between health, education, and health literacy: results from the Dutch Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey. J Health Commun. 2013;18(1):172–184. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.825668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]