Summary

Early-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients are evaluated by end-of-chemotherapy positron emission tomography-computed tomography (eoc-PET-CT) after doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (ABVD) and before radiation therapy (RT). We determined freedom from progression (FFP) in patients treated with ABVD and RT according to the eoc-PET-CT 5-point score (5PS). Secondarily, we assessed whether patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT (5PS of 4–5) can be cured with RT alone. The cohort comprised 174 patients treated for stage I-II HL with ABVD and RT alone. ABVD was given with a median of 4 cycles and RT with a median dose of 30.6 Gy. 5-year FFP was 97%. 5-year FFP was 100% (0 relapses/98 patients) for patients with a 5PS of 1–2, 97% (2/65) for a 5PS of 3 83% (1/8) for a 5PS of 4 and 67% (1/3) for a 5PS of 5 (P<0.001). Patients with positive eoc-PET-CT scans who were selected for salvage RT alone had experienced a very good partial response to ABVD. Risk factors for recurrence in this subgroup included a small reduction in tumour size and a “bounce” in ≥1 PET-CT parameter (reduction then rise from interim to final scan). Thus, a positive eoc-PET-CT is associated with inferior FFP; however, appropriately selected patients can be cured with RT alone.

Keywords: Hodgkin lymphoma, radiation therapy, radiotherapy, salvage, 5-point score

Introduction

A common treatment strategy for early-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is combined modality therapy (CMT) with doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (ABVD) followed by consolidative radiation therapy (RT), as established by the seminal German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) trials (Eich, et al 2010, Engert, et al 2010). This approach results in long-term cure in the majority of patients, in whom minimizing therapy is appropriate to reduce the risk of late treatment-related toxicity. However, a small fraction of patients develops relapsed or refractory disease, which may be fatal. In this subgroup, intensified therapy is recommended to improve disease control. Thus, tools that enable response-adapted individualization of management are highly desirable to avoid over- or under-treatment.

Functional imaging with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scans has become a standard tool for response assessment in HL. Multiple groups have shown that early resolution of FDG-avidity is associated with a decreased risk of disease relapse (Furth, et al 2009, Gallamini, et al 2014, Hutchings, et al 2014, Oki, et al 2014, Simontacchi, et al 2015, Zinzani, et al 2006). Conversely, residual FDG-avidity at the completion of chemotherapy is associated with an increased risk of progression (Advani, et al 2007, Barnes, et al 2011, Furth, et al 2009).

In early-stage HL patients treated with CMT, an end-of-chemotherapy PET-CT (eoc-PET-CT) scan is performed routinely after the completion of ABVD and prior to RT. The Deauville 5-point score (5PS) is used to report disease response to chemotherapy. This score is based upon the FDG uptake of the tumour relative to 2 reference points within the individual patient: the mediastinal blood pool and the liver (Barrington, et al 2014, Cheson, et al 2014). Typically, a 5PS of 1–3 is interpreted as a complete metabolic response, while a score of 4–5 is thought to represent residual active disease (Barrington, et al 2014). While patients with a 5PS of 1–3 continue on to receive the planned consolidative RT, those with a 5PS of 4–5 are managed typically with salvage chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). However, a 5PS of 4–5 represents a spectrum of disease response ranging from partial resolution to progression (Barrington, et al 2014). Therefore, a more nuanced approach toward patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT may be needed.

Previous work has suggested that selected patients with residual FDG-avid disease after completion of chemotherapy may be salvaged with RT alone and spared intensive chemotherapy and ASCT. However, this work was completed primarily in the era preceding use of the 5PS (Engert, et al 2012, Sher, et al 2009). A more recent publication using the 5PS showed that 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) was 97% vs. 78% for early-stage HL patients with a negative vs. positive eoc-PET-CT, respectively (P < 0.0001) (Ciammella, et al 2016). Although the majority of these patients were treated with ABVD and RT, the cohort did include individuals treated with intensified chemotherapy and/or ASCT. The systemic therapy regimen administered influences the predictive accuracy of the eoc-PET-CT; therefore, this study did not provide the outcomes of a cohort treated with ABVD and RT alone.

The current study aimed to assess freedom from progression (FFP) in early-stage HL patients treated with ABVD and RT only, according to the 5PS of the eoc-PET-CT. Secondarily, it aimed to determine whether selected patients with residual PET-positive disease after ABVD (5PS of 4–5) could be cured with RT alone and spared intensive salvage chemotherapy and ASCT. Lastly, it characterized the patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT who were selected for treatment with RT alone and explored innovative factors predictive of successful salvage with RT in this subgroup.

Methods

Patients

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, all patients seen at our institution for Ann Arbor stage I-II HL from 1 January2003 to 31 December 2014 were identified retrospectively. Eligibility criteria for this study included: age ≥18 years, treatment with upfront ABVD or ABVD-like chemotherapy and RT, and availability of an analysable FDG-PET-CT scan performed after chemotherapy and before RT (eoc-PET-CT). RT was given according to the involved site technique (Specht, et al 2014). Clinical information was retrieved from electronic medical records.

Definitions

Bulky disease was defined as a tumour diameter of >10 cm in any dimension. FFP was defined as the time from initial diagnosis to diagnosis with relapsed/refractory disease. The eoc-PET-CT was performed after the completion of all cycles of ABVD, and PET-positivity was defined as a 5PS of 4 or 5.

PET-CT acquisition

Patients fasted for at least 6 h and were confirmed to have a blood glucose level of <8.325 mmol/l prior to the FDG injection. For the FDG-PET-CT scan, patients were positioned supine. The FDG dose was 555–629 MBq for 2D imaging and 333–407 MBq for 3D imaging. Emission scans were acquired between 60 and 90 min after the FDG injection. Standard, vendor-provided reconstruction algorithms were used for PET images. CT images were acquired in helical mode during suspended mid-expiration. All PET-CT scanners underwent routine quality assurance.

PET-CT analysis

All PET-CT scans were interpreted clinically by trained Nuclear Medicine Radiologists. A 5PS was assigned as reported previously (Barrington, et al 2014, Cheson, et al 2014). Two investigators performed exploratory PET-CT analyses using MIM software version 6.4.9 (MIM Software Inc, Cleveland, Ohio). The maximum body weight standardized uptake value (SUV) of the disease was recorded. The metabolic tumour volume (MTV), defined as all disease with an SUV ≥2.5 (Freudenberg, et al 2004), was automatically contoured using a threshold segmentation method. The total lesion glycolysis (TLG) was defined as MTV×mean SUV of the MTV. The soft tissue volume (STV), defined as all abnormal tissue noted on the CT scan, was contoured manually. The reduction in each parameter was defined as 1 – (value from final PET-CT/corresponding value from initial PET-CT).

Statistical methods

The primary outcome was FFP, defined as the time from initial diagnosis to diagnosis with relapsed/refractory disease. If no event occurred, patients were censored at the time of last follow-up. Survival analyses were performed using Kaplan-Meier methods and compared using the log-rank test. Univariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to determine the effect of covariates on FFP. Categorical and continuous variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test and the two-tailed t-test, respectively. Analyses were conducted using SPSS software (Version 22.0. IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

Results

Patient, disease, and treatment information

During the study period, 396 patients aged at least 18 years were seen at our institution for a diagnosis of early-stage HL. Of these, 174 patients were treated with ABVD and RT and had an available, analysable eoc-PET-CT scan. These patients comprised the study cohort.

The characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Table I. The median age at diagnosis was 31 years (range: 18–83). Disease was stage II in 142 (82%). B symptoms were present in 53 patients (31%) and bulk in 52 (30%). Patients received a median of 4 cycles of ABVD (range: 2–6), and RT was to a median dose of 30.6 Gy (range: 20–42.2 Gy). The post-chemotherapy 5PS was 1–2 in 98 patients (56%), 3 in 65 (37%), 4 in 8 (5%), and 5 in 3 (2%). Patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT who were treated with salvage chemotherapy/ASCT did not meet the inclusion criteria for this study and, therefore, are not represented in this group. This separate cohort is described below.

Table I.

Patient, disease, and treatment characteristics of early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma patients treated with ABVD and RT (n = 174)

| Characteristic | Number |

|---|---|

| Median Age (Range), years | 31 (18–83) |

| Stage I / Stage II | 32 (18%) / 142 (82%) |

| B Symptoms | 53 (31%) |

| Bulk | 52 (30%) |

| Extranodal disease | 9 (5%) |

| Median Number of ABVD Cycles (Range) | 4 (2–6) |

| Median RT Dose (Range), Gy | 30.6 (20–42.2) |

ABVD = doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine

RT = radiation therapy

Patient outcomes

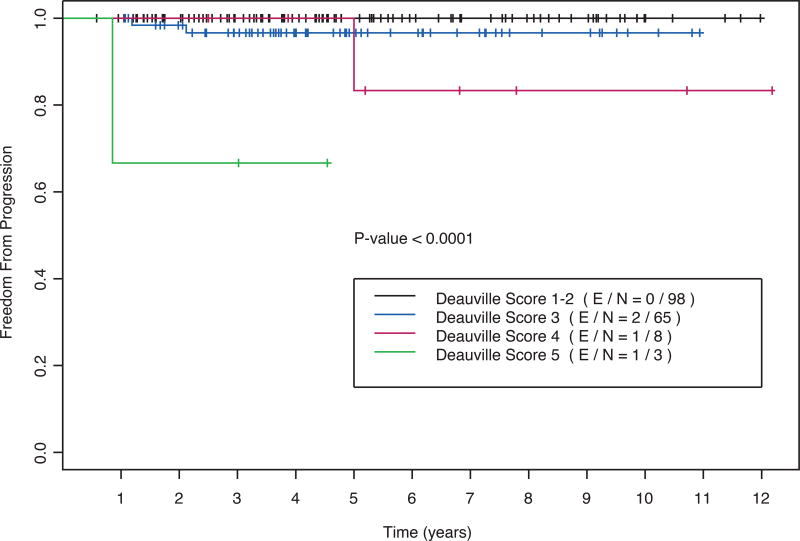

At a median follow-up of 53 months (range: 7–146), 4 events were observed. Two disease relapses were local (i.e. within the RT field), one was distant, and one was both local and distant. The 5-year actuarial FFP was 97% (95% confidence interval: 94–100%). As shown in Table II and Figure 1, the post-chemotherapy 5PS was significantly associated with FFP (P < 0.001). The 5-year FFP was 100% for patients with a 5PS of 1–2, 97% for a 5PS of 3, 83% for a 5PS of 4 and 67% for a 5PS of 5

Table II.

Deauville 5-point score and freedom from progression for early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma patients selected to receive ABVD and RT (n = 174)

| Deauville 5-Point Score | n (% cohort) | Events | 5-Year FFP (95% CI) | Log-Rank P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 98 (56%) | 0 | 100% | P < 0.001 |

| 3 | 65 (37%) | 2 | 97% (92–100%) | |

| 4 | 8 (5%) | 1 | 83% (53–100%) | |

| 5 | 3 (2%) | 1 | 67% (13–100%) |

FFP = freedom from progression

95% CI = 95% confidence interval

Figure 1.

Freedom from progression as a function of the eoc-PET-CT Deauville 5-point score (5PS) for patients selected for treatment with ABVD and RT (n = 174). Log-rank P < 0.001.

eoc-PET-positive subgroup

Patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT after the completion of ABVD are typically considered for salvage chemotherapy and ASCT. We aimed to characterize the patients with residual PET-positive disease who were selected for treatment with RT alone and, therefore, were included in this cohort. Thus, we identified a comparison group comprising the patients who were managed during the same time period, had a positive eoc-PET-CT, and were treated with salvage chemotherapy/ASCT. A total of 15 patients met these criteria. It must be noted that these 15 patients who received salvage chemotherapy and underwent ASCT for primary refractory HL were not included in the survival analyses reported above.

The characteristics of patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT who were managed with these 2 approaches are compared in Table III. Patients treated with salvage chemotherapy/ASCT were significantly more likely to have undergone a biopsy after completion of ABVD and to have pathologically confirmed refractory HL. Those selected for RT alone had a lower burden of persistent disease on the eoc-PET-CT. For example, the median final MTV was 2.2 ml vs. 14 ml and median final STV was 21 ml vs. 50 ml in patients treated with RT alone vs. salvage chemotherapy/ASCT. Every patient selected for RT alone had experienced a very good partial response to ABVD. Comparing the eoc- to the pre-chemotherapy PET-CT, the median reduction in MTV was 99% and in STV was 85%. In one patient treated with RT, there was an increase in SUVmax from the pre-chemotherapy to eoc-PET-CT; however, the area of increased FDG-avidity was of small volume, reflected by the significant reduction in MTV. All patients with stable or progressive disease were treated with salvage chemotherapy/ASCT. These patients had higher risk disease, confirmed by their inferior outcomes, despite receipt of more intensive therapy. In the ASCT group, 6 patients (40%) experienced disease relapse after ASCT and 3 (20%) died of HL; in the RT group, 2 patients (18%) experienced disease relapse after RT and 1 (9%) died of HL.

Table III.

Characteristics of patients with positive eoc-PET/CT scans after ABVD who were selected for treatment with RT alone (n = 11; included in the current study cohort) vs. salvage chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (n = 15; not included in the current study cohort)

| Characteristic | RT Alone (n = 11) | Salvage Chemotherapy/ASCT (n = 15) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age (Range), years | 25 (20–70) | 28 (20–41) | 0.3 |

| Stage I / Stage II | 0 (0%) / 11 (100%) | 0 (0%) / 15 (100%) | |

| Bulk | 4 (36%) | 4 (27%) | 0.7 |

| Extranodal disease | 1 (9%) | 1 (7%) | 1.0 |

| Median Number of ABVD Cycles (Range) | 6 (4–6) | 6 (4–6) | 0.6 |

| Biopsies Performed | 3 (27%) | 13 (87%) | 0.004 |

| Biopsies Positive | 1 (9% of cohort; 33% of biopsies) | 13 (87% of cohort; 100% of biopsies) | <0.001 |

| Median Final SUVmax (Range) | 4.9 (2.7–11.5) | 9.0 (2.5–20) | 0.02 |

| Median Final MTV (Range), ml | 2.2 (0.1–19) | 14 (1.4–648) | 0.2 |

| Median Final TLG (Range) | 7.1 (0.3–73) | 48 (4.1–4497) | 0.3 |

| Median Final STV (Range), ml | 21 (2.6–236) | 50 (11–883) | 0.04 |

| Median SUVmax Reduction (Range) | 63% (−87–77%) | 26% (−120–68%) | 0.2 |

| Median MTV Reduction (Range) | 99% (83–100%) | 94% (20–98%) | 0.09 |

| Median TLG Reduction (Range) | 99% (88–100%) | 97% (26–99%) | 0.09 |

| Median STV Reduction (Range) | 85% (59–95%) | 83% (−10–90%) | 0.1 |

ABVD = doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine

ASCT = autologous stem cell transplant

MTV = metabolic tumour volume

RT = radiation therapy

STV = soft tissue volume

SUVmax = maximum standardized uptake value

TLG = total lesion glycolysis

The remainder of the analysis focused on the 11 patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT who were treated with RT only, without salvage chemotherapy or ASCT. All patients presented with stage II HL and 4 (36%) had bulky disease. These patients received a median of 6 cycles of ABVD (range: 4–6), and RT was to a median dose of 37.8 Gy (range: 30.6–42.2 Gy). A biopsy was performed prior to RT for 3 patients (27%) and was positive for persistent HL in 1 case (9% of subgroup, 33% of biopsies).

After the completion of RT, 2 of 11 patients (18%) in this subset experienced disease progression. Of these, 1 relapse was local (i.e. within the RT field) and the second was both local and distant. Univariate analyses were performed to compare the 2 patients whose disease relapsed with the remaining 9 patients who were salvaged successfully with RT. As shown in Table IV, the only factor that was significantly associated with FFP was change in STV. Specifically, patients whose disease progressed experienced a smaller reduction in tumour size during chemotherapy. The STV reduction ranged from 59–61% in patients whose disease relapsed, compared to 78–95% in patients whose disease did not relapse (P < 0.001).

Table IV.

Univariate analyses of factors associated with freedom from progression in the patients with residual PET-positive disease who were selected to receive salvage RT alone (n = 11)

| Characteristic | No Progression (n = 9) | Progression (n = 2) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| B Symptoms | 3 (33%) | 1 (50%) | 1.0 |

| Bulk | 3 (33%) | 1 (50%) | 1.0 |

| Median Number of ABVD Cycles (Range) | 6 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.7 |

| Median RT Dose (Range), Gy | 37.8 (30.6–42.2) | 37.8 (36–39.6) | 0.5 |

| Biopsy-Proven Residual Disease | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 0.2 |

| Median Final SUVmax (Range) | 4.9 (3.0–9.6) | 7.1 (2.7–11.5) | 0.8 |

| Median Final MTV (Range), ml | 2.2 (0.9–5.5) | 9.5 (0.1–19) | 0.6 |

| Median Final TLG (Range) | 7.1 (1.0–22) | 37 (0.3–73) | 0.6 |

| Median Final STV (Range), ml | 16 (2.6–87) | 129 (21–236) | 0.5 |

| Median SUVmax Reduction (Range) | 63% (43–77%) | −6% (−87–74%) | 0.6 |

| Median MTV Reduction (Range) | 99% (83–99%) | 96% (92–100%) | 0.9 |

| Median TLG Reduction (Range) | 99% (88–100%) | 95% (90–100%) | 0.5 |

| Median STV Reduction (Range) | 89% (78–95%) | 60% (59–61%) | 0.001 |

ABVD = doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine

MTV = metabolic tumour volume

RT = radiation therapy

STV = soft tissue volume

SUVmax = maximum standardized uptake value

TLG = total lesion glycolysis

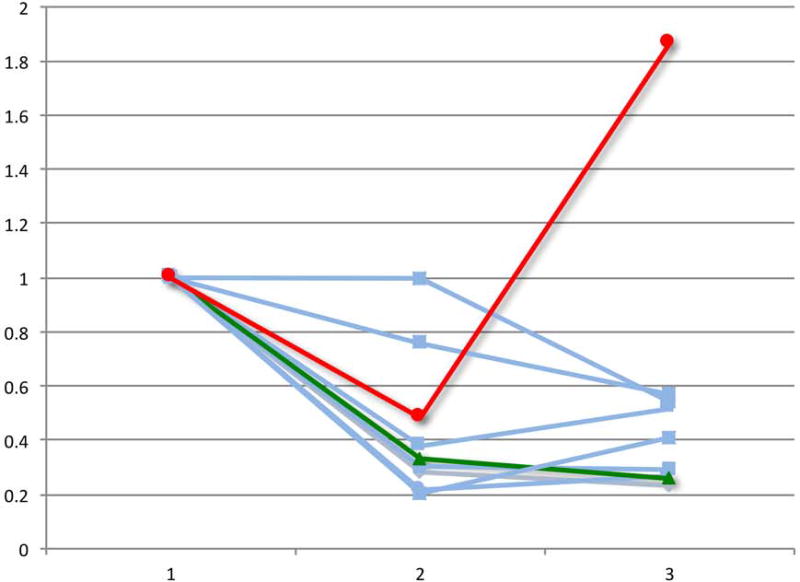

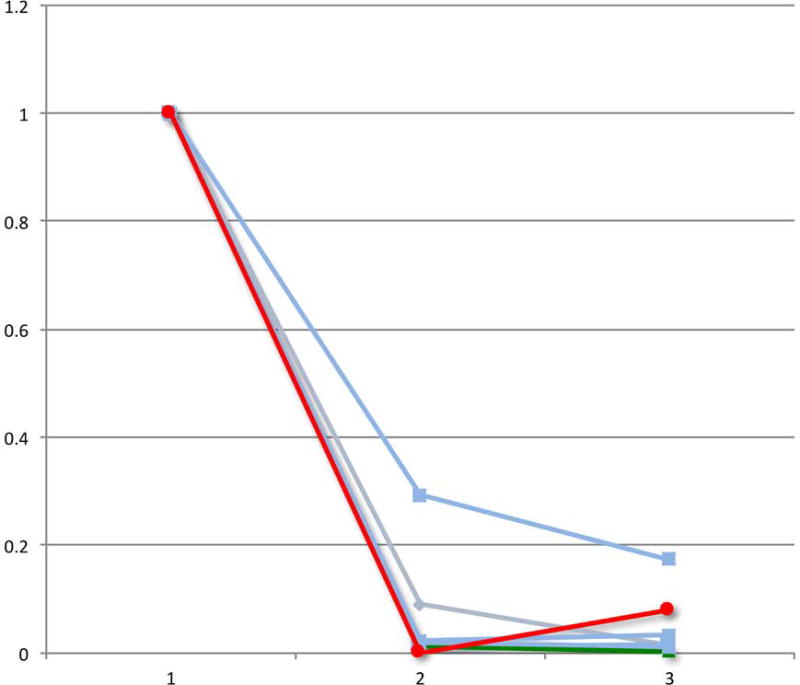

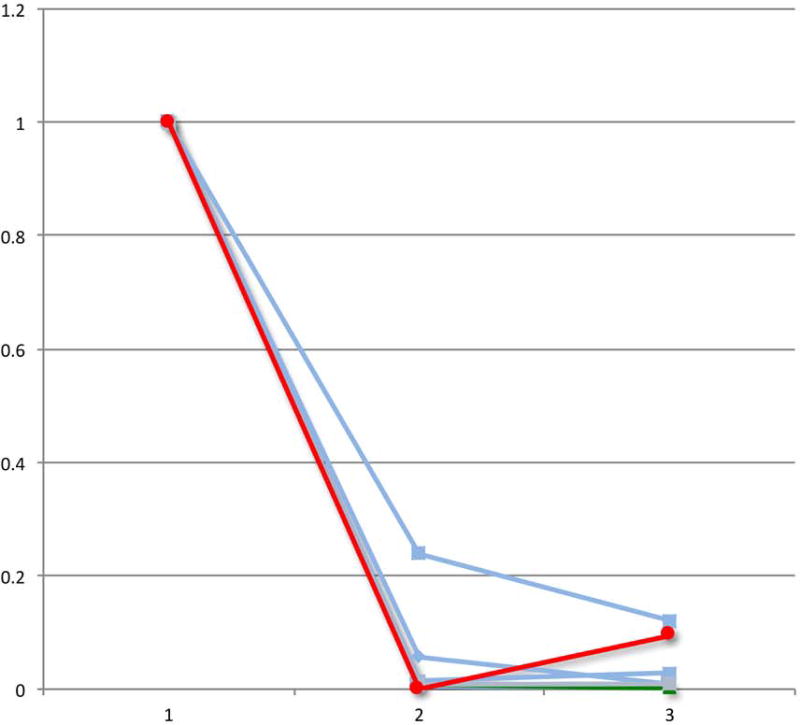

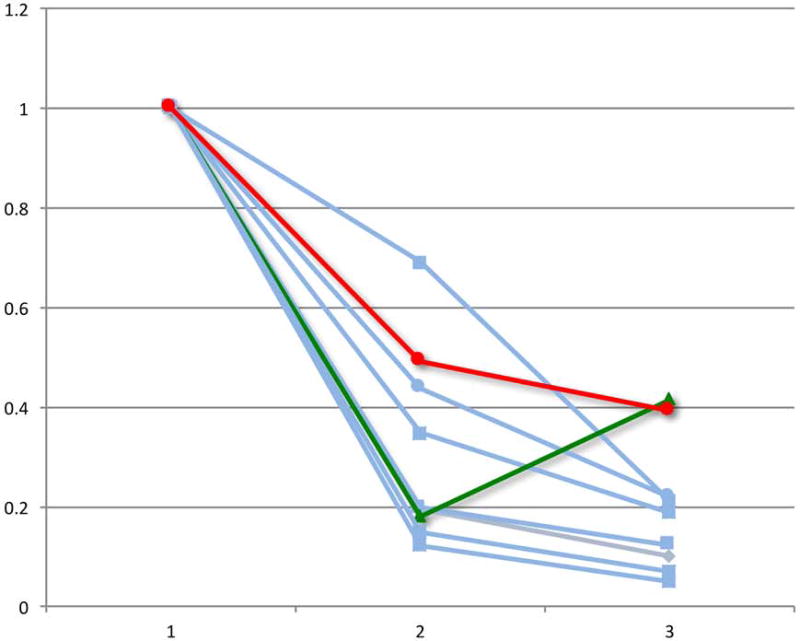

Lastly, we evaluated the change in PET-CT parameters over the course of chemotherapy in patients who had a pre-chemotherapy, interim and eoc-PET-CT scan. Of the patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT who were treated with RT alone, 9 had scans performed at these 3 time points, including the 2 patients who experienced a disease relapse after RT. With the caveat of small numbers, we observed that both patients whose disease relapsed experienced a “bounce” in at least one PET or CT parameter, defined as a reduction in the value from the pre-chemotherapy to the interim scan followed by an increase in the value from the interim to the eoc-PET-CT scan (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relative change in PET-CT parameters during the course of chemotherapy for the select group of eoc-PET-positive patients who received salvage RT alone. The graphs demonstrate positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) measurements for patients with pre-chemotherapy (1), interim (2), and post-chemotherapy (3) scans (n = 9). The 2 patients with subsequent relapse (red and green) experienced a “bounce” in ≥1 final PET or CT parameter, defined as a reduction in the value from the pre-chemotherapy to the interim scan followed by an increase in the value from the interim to the end-of-chemotherapy-PET-CT scan.

A) Relative change in maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax)

B) Relative change in metabolic tumour volume (MTV)

C) Relative change in total lesion glycolysis (TLG)

D) Relative change in soft tissue volume (STV)

Discussion

In this cohort of early-stage classical HL patients treated with ABVD and RT, the post-chemotherapy 5PS was significantly associated with FFP. However, although patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT were at an increased risk of disease progression, the majority were salvaged with RT alone. The patients with residual PET-positivity who were selected for treatment with RT alone had experienced a very good partial response to ABVD and had only low volume residual FDG-avidity at the completion of chemotherapy. For this subgroup, the median reduction in STV was 85% and in MTV was 99%, reflecting a significant anatomic and metabolic response. Patients with highly refractory disease were not treated with this strategy and were not included in this cohort; instead, such patients were directed to salvage chemotherapy/ASCT. Thus, our data suggest that patients with an incomplete but good partial disease response to ABVD can be cured with RT alone, without the need for intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation.

Previously published data support the conclusion that a significant proportion of HL patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT can be cured with RT. Sher et al (2009) reported on 73 patients with HL of any stage, who were treated with ABVD-based chemotherapy and RT. For the 13 patients with residual PET-positivity after ABVD, failure-free survival was 69% at 2 years after treatment with RT only . Similarly, in the GHSG HD15 trial, patients with advanced-stage HL were treated with bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine and prednisone (BEACOPP). Subsequently, RT was given for patients with residual disease measuring ≥2.5 cm that was PET-positive. For the 182 patients who met these criteria, PFS was 86.2% at 2 years (Engert, et al 2012). Thus, in both studies, RT effectively salvaged the majority of patients with persistent FDG-avid disease after chemotherapy. Of note, these studies pre-dated the routine use of the 5PS, so PET-positivity was defined as residual FDG uptake above the mediastinal blood pool for masses measuring >2 cm or above background for smaller masses (Juweid, et al 2007).

The current study not only corroborates these previously published findings, but also provides valuable new information. Unlike these other studies, our work was conducted in the era of the Deauville 5PS. The 5PS allows accurate response assessment. Each patient acts as his or her own control, so inter-reader and inter-device inconsistencies are reduced (Barrington, et al 2010). The 5PS has become the accepted standard for reporting disease response to therapy in HL. Therefore, our findings are applicable to early-stage HL patients treated with ABVD and RT in the current era.

Another study published in the era of the 5PS reported findings consistent with ours. Ciammella et al (2016) evaluated the prognostic role of the eoc-PET-CT in 165 early-stage HL patients treated with CMT. They found that 5-year PFS was 97% vs. 78% for patients with a 5PS of 1–3 vs. 4–5, respectively (P < 0.0001). As in our study, the eoc-PET-CT 5PS was significantly associated with outcome; nonetheless, the majority of patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT were salvaged successfully. In their study, most patients were treated with ABVD and RT; however, the cohort did include individuals treated with intensified chemotherapy (ex. BEACOPP) and/or ASCT. Thus, our study is unique in that it provides the outcomes of a cohort treated uniformly with ABVD and RT alone.

Furthermore, we analysed the subgroup of patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT who were treated with RT alone to identify factors that distinguished those who were salvaged effectively by RT from those who experienced a subsequent disease relapse. This assessment was limited by small patient numbers. Nonetheless, several features were notable. First, the only patient with biopsy-proven residual disease after chemotherapy experienced disease progression. Second, the 2 patients in this group whose disease relapsed after RT were those who had experienced the smallest reduction in soft tissue volume over the course of ABVD. This finding supports previously published work showing that lack of reduction in tumour size is a risk factor for recurrence, independent of the Deauville 5PS (Kostakoglu, et al 2012, Milgrom, et al 2017). Consistent with this result, in patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT who were treated with RT on the GHSG HD15 trial, a smaller reduction in size of the CT mass was associated with a higher risk of disease relapse (Kobe, et al 2014). Our analysis was limited by the small number of patients; therefore, further study is needed to define quantitatively an adequate STV reduction in this setting. The final feature that distinguished the 2 individuals whose disease relapsed was that both experienced a “bounce,” defined as an increase in one or more eoc-PET-CT parameters relative to interim scans. To the best of our knowledge, the prognostic implications of this “bounce” phenomenon have not been reported previously.

We conclude that selected patients with a post-chemotherapy 5PS of 4–5, who have experienced a very good partial response to ABVD, can be salvaged with RT alone. Patients with biopsy-proven residual disease, poor tumour shrinkage, or a “bounce” in any PET-CT parameter may not be optimal candidates for this approach. We hypothesize that 1) a positive biopsy after ABVD, 2) a small reduction in tumour size, and/or 3) an increase in SUVmax, MTV, TLG or STV between the interim and final scan may signify that disease is truly refractory to chemotherapy. Conversely, in patients with a positive eoc-PET-CT who do not have these characteristics, persistent FDG-avidity may represent low-level, residual chemosensitive disease or post-treatment inflammation, so RT is more likely to be sufficient for cure.

In the present study, all patients were treated with ABVD and RT. This treatment approach is used routinely at our institution. For patients who achieve at least a good partial response to ABVD based on interim PET-CT scans, typically performed after 2 cycles, we continue treatment with the same chemotherapy. Then, based on the results of the eoc-PET-CT, the decision is made whether to proceed with the planned RT or with salvage systemic therapy in patients with persistent disease. However, recently published data support escalation of chemotherapy, prior to RT, as a part of frontline management in patients with a positive interim PET-CT. In the randomized European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer / Lymphoma Study Association /Fondazione Italiana Linfomi H10 trial, patients with a positive PET-CT after 2 cycles of ABVD received either continued ABVD followed by RT or intensification of chemotherapy with escalated BEACOPP followed by RT. In this interim PET-positive subgroup, patients treated with escalated BEACOPP experienced significantly improved PFS (Andre, et al 2017). Thus, it is possible that patients in our current study may have experienced superior outcomes with intensification of their systemic therapy. We have not adopted this approach as our standard practice, because we have observed excellent clinical outcomes with ABVD and RT, so we prefer to avoid the higher toxicity rates associated with BEACOPP. Nonetheless, escalation of chemotherapy may be appropriate, in some scenarios, to improve disease control after upfront therapy and reduce the need for salvage treatment.

The current work is not without limitations. First, the small number of events limited the statistical analyses. Second, the retrospective design predisposed to bias. For example, eoc-PET-CT data were not available for all patients treated with ABVD and RT during the study period, so it is possible that those patients with eoc-PET-CT scans did not accurately represent the complete population. For example, patients with equivocal interim PET-CT scans may have been more likely to be evaluated by an eoc-PET-CT and thus may have been over-represented in this study. Given these limitations, validation of our findings in larger patient populations and in prospective studies is encouraged.

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths, including uniform therapy with ABVD or ABVD-like chemotherapy and RT and long patient follow-up. For the subgroup of patients with persistent PET-positive disease treated with RT alone, the minimum follow-up time was 30 months. Therefore, it is likely that all events were captured, since the majority of relapses occur within 2 years after treatment for early-stage HL (Eich, et al 2010).

Modern management of HL focuses on response-adapted individualization to minimize toxicity while maintaining high cure rates. Therapy may be de-escalated in the setting of chemosensitive disease, for example, by limiting the number of chemotherapy cycles or omitting RT. Conversely, therapy is intensified for refractory disease, typically with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. Here, we have identified an intermediate group that has residual PET-positive disease after the completion of ABVD, but can be cured with RT alone. These patients can be spared the morbidity of high-dose chemotherapy and ASCT. Further work is needed to characterize this group, so they may avoid overly intensive therapy.

Key Message.

In early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma patients treated with doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (ABVD) and radiation therapy (RT), the post-chemotherapy 5-point score (5PS) was associated with risk of progression. Nonetheless, select patients with residual PET-positive disease (5PS of 4–5) after ABVD were cured with RT alone. Such patients may be spared intensive salvage therapies.

Acknowledgments

Grant: NIH/NCI P30 CA16672

Funding:

none declared

Footnotes

Competing interests:

The authors have no competing interests

Author contributions:

Conception and design: SAM, CCP, GLS, BSD

Collection and assembly of data: SAM, HC, MA, JRG, JPR, OM, NG, ER, EMO, ZAY

Data analysis and interpretation: SAM, CCP, HC, YO, MA, JRG, JPR, GLS, OM, NG, ER, FBH, HJL, LEF, WD, EMO, ZAY, MF, BSD

Manuscript writing: SAM

Final approval of manuscript: SAM, CCP, HC, YO, MA, JRG, JPR, GLS, OM, NG, ER, FBH, HJL, LEF, WD, EMO, AQY, MF, BSD

Provision of patients: SAM, CCP, YO, GLS, FBH, HJL, LEF, MF, BSD

References

- Advani R, Maeda L, Lavori P, Quon A, Hoppe R, Breslin S, Rosenberg SA, Horning SJ. Impact of positive positron emission tomography on prediction of freedom from progression after Stanford V chemotherapy in Hodgkin's disease. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3902–3907. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre MPE, Girinsky T, Federico M, Reman O, Fortpied C, Gotti M, Casasnovas O, Brice P, van der Maazen R, Re A, Edeline V, Ferme C, van Imhoff G, Merli F, Bouabdallah R, Sebban C, Specht L, Stamatoullas A, Delarue R, Fiaccadori V, Bellei M, Raveloarivahy T, Versari A, Hutchings M, Meignan M, Raemaekers J. Early Positron Emission Tomography Response-Adapted Treatment in Stage I and II Hodgkin Lymphoma: Final Results of the Randomized EORTC/LYSA/FIL H10 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1786–1794. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.6394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes JA, LaCasce AS, Zukotynski K, Israel D, Feng Y, Neuberg D, Toomey CE, Hochberg EP, Canellos GP, Abramson JS. End-of-treatment but not interim PET scan predicts outcome in nonbulky limited-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:910–915. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington SF, Qian W, Somer EJ, Franceschetto A, Bagni B, Brun E, Almquist H, Loft A, Hojgaard L, Federico M, Gallamini A, Smith P, Johnson P, Radford J, O'Doherty MJ. Concordance between four European centres of PET reporting criteria designed for use in multicentre trials in Hodgkin lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1824–1833. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, Kostakoglu L, Meignan M, Hutchings M, Mueller SP, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, Fisher RI, Trotman J, Hoekstra OS, Hicks RJ, O'Doherty MJ, Hustinx R, Biggi A, Cheson BD. Role of imaging in the staging and response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas Imaging Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3048–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, Lister TA, Alliance AL, Lymphoma G, Eastern Cooperative Oncology, G. European Mantle Cell Lymphoma, C. Italian Lymphoma, F. European Organisation for, R. Treatment of Cancer/Dutch Hemato-Oncology, G. Grupo Espanol de Medula, O. German High-Grade Lymphoma Study, G. German Hodgkin's Study, G. Japanese Lymphorra Study, G. Lymphoma Study, A. Group, N.C.T. Nordic Lymphoma Study, G. Southwest Oncology, G. United Kingdom National Cancer Research, I Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3059–3068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciammella P, Filippi AR, Simontacchi G, Buglione M, Botto B, Mangoni M, Iotti C, Merli F, Marcheselli L, Bisi G, Ricardi U, Versari A. Post-ABVD/pre-radiotherapy (18)F-FDG-PET provides additional prognostic information for early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma: a retrospective analysis on 165 patients. Br J Radiol. 2016;89:20150983. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eich HT, Diehl V, Gorgen H, Pabst T, Markova J, Debus J, Ho A, Dorken B, Rank A, Grosu AL, Wiegel T, Karstens JH, Greil R, Willich N, Schmidberger H, Dohner H, Borchmann P, Muller-Hermelink HK, Muller RP, Engert A. Intensified chemotherapy and dose-reduced involved-field radiotherapy in patients with early unfavorable Hodgkin's lymphoma: final analysis of the German Hodgkin Study Group HD11 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4199–4206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.8018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engert A, Plutschow A, Eich HT, Lohri A, Dorken B, Borchmann P, Berger B, Greil R, Willborn KC, Wilhelm M, Debus J, Eble MJ, Sokler M, Ho A, Rank A, Ganser A, Trumper L, Bokemeyer C, Kirchner H, Schubert J, Kral Z, Fuchs M, Muller-Hermelink HK, Muller RP, Diehl V. Reduced treatment intensity in patients with early-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:640–652. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engert A, Haverkamp H, Kobe C, Markova J, Renner C, Ho A, Zijlstra J, Kral Z, Fuchs M, Hallek M, Kanz L, Dohner H, Dorken B, Engel N, Topp M, Klutmann S, Amthauer H, Bockisch A, Kluge R, Kratochwil C, Schober O, Greil R, Andreesen R, Kneba M, Pfreundschuh M, Stein H, Eich HT, Muller RP, Dietlein M, Borchmann P, Diehl V. Reduced-intensity chemotherapy and PET-guided radiotherapy in patients with advanced stage Hodgkin's lymphoma (HD15 trial): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1791–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61940-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg LS, Antoch G, Schutt P, Beyer T, Jentzen W, Muller SP, Gorges R, Nowrousian MR, Bockisch A, Debatin JF. FDG-PET/CT in re-staging of patients with lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:325–329. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1375-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furth C, Steffen IG, Amthauer H, Ruf J, Misch D, Schonberger S, Kobe C, Denecke T, Stover B, Hautzel H, Henze G, Hundsdoerfer P. Early and late therapy response assessment with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in pediatric Hodgkin's lymphoma: analysis of a prospective multicenter trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4385–4391. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.7814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallamini A, Barrington SF, Biggi A, Chauvie S, Kostakoglu L, Gregianin M, Meignan M, Mikhaeel GN, Loft A, Zaucha JM, Seymour JF, Hofman MS, Rigacci L, Pulsoni A, Coleman M, Dann EJ, Trentin L, Casasnovas O, Rusconi C, Brice P, Bolis S, Viviani S, Salvi F, Luminari S, Hutchings M. The predictive role of interim positron emission tomography for Hodgkin lymphoma treatment outcome is confirmed using the interpretation criteria of the Deauville five-point scale. Haematologica. 2014;99:1107–1113. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.103218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings M, Kostakoglu L, Zaucha JM, Malkowski B, Biggi A, Danielewicz I, Loft A, Specht L, Lamonica D, Czuczman MS, Nanni C, Zinzani PL, Diehl L, Stern R, Coleman M. In vivo treatment sensitivity testing with positron emission tomography/computed tomography after one cycle of chemotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2705–2711. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juweid ME, Stroobants S, Hoekstra OS, Mottaghy FM, Dietlein M, Guermazi A, Wiseman GA, Kostakoglu L, Scheidhauer K, Buck A, Naumann R, Spaepen K, Hicks RJ, Weber WA, Reske SN, Schwaiger M, Schwartz LH, Zijlstra JM, Siegel BA, Cheson BD, Imaging Subcommittee of International Harmonization Project in L Use of positron emission tomography for response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the Imaging Subcommittee of International Harmonization Project in Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:571–578. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobe C, Kuhnert G, Kahraman D, Haverkamp H, Eich HT, Franke M, Persigehl T, Klutmann S, Amthauer H, Bockisch A, Kluge R, Wolf HH, Maintz D, Fuchs M, Borchmann P, Diehl V, Drzezga A, Engert A, Dietlein M. Assessment of tumor size reduction improves outcome prediction of positron emission tomography/computed tomography after chemotherapy in advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1776–1781. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostakoglu L, Schoder H, Johnson JL, Hall NC, Schwartz LH, Straus DJ, LaCasce AS, Jung SH, Bartlett NL, Canellos GP, Cheson BD, Cancer Leukemia Group B. Interim [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in stage I-II non-bulky Hodgkin lymphoma: would using combined positron emission tomography and computed tomography criteria better predict response than each test alone? Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:2143–2150. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.676173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom SA, Dong W, Akhtari M, Smith GL, Pinnix CC, Mawlawi O, Rohren E, Garg N, Chuang H, Yehia ZA, Reddy JP, Gunther JR, Khoury JD, Suki T, Osborne EM, Oki Y, Fanale M, Dabaja BS. Chemotherapy Response Assessment by FDG-PET-CT in Early-Stage Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma: Moving Beyond the 5-Point Deauville Score. International Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics. 2017;97:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oki Y, Chuang H, Chasen B, Jessop A, Pan T, Fanale M, Dabaja B, Fowler N, Romaguera J, Fayad L, Hagemeister F, Rodriguez MA, Neelapu S, Samaniego F, Kwak L, Younes A. The prognostic value of interim positron emission tomography scan in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2014;165:112–116. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher DJ, Mauch PM, Van Den Abbeele A, LaCasce AS, Czerminski J, Ng AK. Prognostic significance of mid- and post-ABVD PET imaging in Hodgkin's lymphoma: the importance of involved-field radiotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1848–1853. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simontacchi G, Filippi AR, Ciammella P, Buglione M, Saieva C, Magrini SM, Livi L, Iotti C, Botto B, Vaggelli L, Re A, Merli F, Ricardi U. Interim PET After Two ABVD Cycles in Early-Stage Hodgkin Lymphoma: Outcomes Following the Continuation of Chemotherapy Plus Radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92:1077–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specht L, Yahalom J, Illidge T, Berthelsen AK, Constine LS, Eich HT, Girinsky T, Hoppe RT, Mauch P, Mikhaeel NG, Ng A, Ilrog Modern radiation therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma: field and dose guidelines from the international lymphoma radiation oncology group (ILROG) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89:854–862. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzani PL, Tani M, Fanti S, Alinari L, Musuraca G, Marchi E, Stefoni V, Castellucci P, Fina M, Farshad M, Pileri S, Baccarani M. Early positron emission tomography (PET) restaging: a predictive final response in Hodgkin's disease patients. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1296–1300. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]