Abstract

The purpose of this article was to systematically review yoga interventions aimed at improving depressive symptoms. A total of 23 interventions published between 2011 and May 2016 were evaluated in this review. Three study designs were used: randomized control trials, quasi-experimental, and pretest/posttest, with majority being randomized control trials. Most of the studies were in the United States. Various yoga schools were used, with the most common being Hatha yoga. The number of participants participating in the studies ranged from 14 to 136, implying that most studies had a small sample. The duration of the intervention period varied greatly, with the majority being 6 weeks or longer. Limitations of the interventions involved the small sample sizes used by the majority of the studies, most studies examining the short-term effect of yoga for depression, and the nonutilization of behavioral theories. Despite the limitations, it can be concluded that the yoga interventions were effective in reducing depression.

Keywords: yoga, depression

Depression is one of the most common mental illnesses in the world. It is estimated that there are 350 million people worldwide who have some form of depression.1 In the United States, 16 million people had a depressive episode in the past year.2 A condition affecting one’s mood and action, depression can affect one’s life substantially. According to the most recent World Health Organization, depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide and is believed to be a major contributor to the overall global burden of disease.1

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, Fifth Edition, has defined depression as 5 or more of the following symptoms that are present for 2 or more weeks and cause significant emotional distress and/or impairment in functioning. Symptoms are depressed or sad mood, short-tempered or easily annoyed, loss of interest or enjoyment in hobbies or activities that was previously enjoyed, feeling of worthlessness or guilt, thoughts of death or suicide, difficulty with concentrating or making decisions, feeling tired or fatigue, feeling restless or slow, changes in appetite such as overeating or loss of appetite, changes in weight such as weight loss or weight gain, and changes in sleep pattern.3 According to the National Institute of Mental Health, depression occurs due to a combination of genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors.4 Treatment for depression consists of participation in psychotherapy, taking antidepressants, or a combination of both. However, many individuals do not participate in psychotherapy or antidepressants due to factors such as unmet needs, side effects, lack of access/resource, and personal choice.

Currently, researchers are studying the efficacy and effectiveness of mind-body interventions such as yoga as an alternative and complementary treatment for depression. Yoga, with its origin in ancient India, is recognized as a form of alternative medicine that implements mind-body practices. The philosophy of yoga is based on 8 limbs that are better described as ethical principles for meaningful and purposeful living.5 While there is no specific definition, yoga has been interpreted as a process of uniting the body via mind and spirit to promote physical and mental wellness.

Yoga practices can utilize any or all the 8 limbs. They generally involve relaxation (shava asana), physical postures (asana), breathing regulation techniques (pranayama), and meditation (dhyana). While there are different schools of yoga, some common schools include Ananda, Anusara, Ashtanga, Bikram, Iyengar, Integral, Kundalani, Kripalu, Power, Prana, Sivananda, and Vinyasa. Types of yoga include alignment-oriented yoga, fitness yoga, flow yoga, gentle yoga, hot yoga, specialty yoga, and spiritual-oriented yoga.

There have been some known benefits of yoga. Per Woodard,5 yoga improves flexibility, can loosen muscles resulting in reduced aches and pain, generates balanced energy, reduces breathing and heart rates, lowers blood pressure and cortisol levels, increase blood flow, and reduces stress and anxiety due to calmness. Yoga practices can thus improve preexisting medical conditions such as arthritis, cancer, mental illness symptoms, and so on.

There is a body of research supporting the use of yoga to reduce depression or depressive symptoms. Mehta and Sharma6 published a systematic review of literature on yoga and depression, searching research articles in English from 2005 to June 2010. They reviewed 18 studies describing the extent to which yoga has been found to be beneficial as a complementary therapy for depression and depressive symptoms. The purpose of this review was to identify newer studies after 2011 and ascertain the efficacy of yoga on depression. Based on this review, recommendations for future interventions have been developed.

Methodology

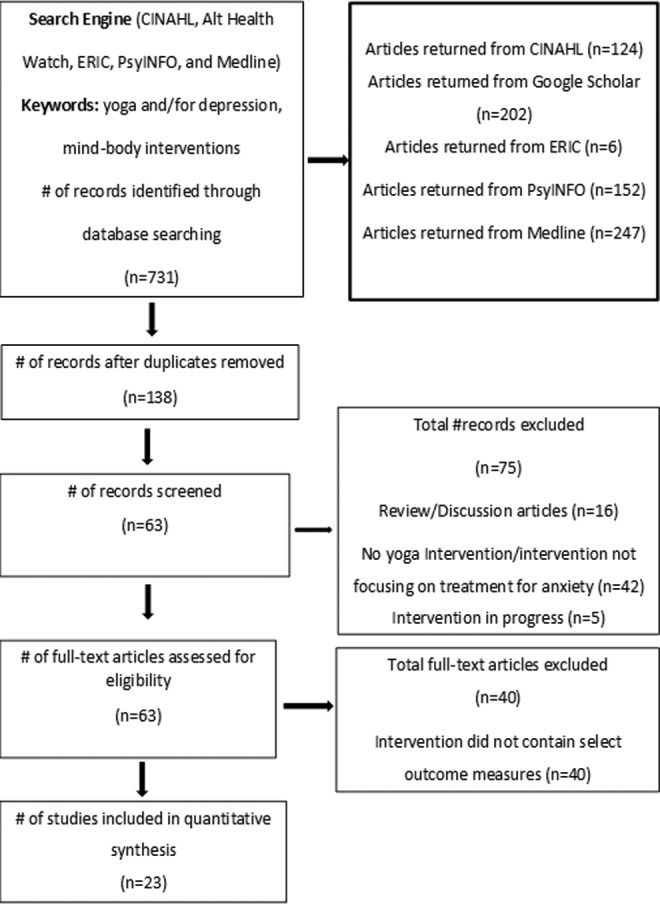

An extensive literature search was conducted to collect studies for inclusion in this review. Studies were identified through electronic database searches of Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Google Scholar, Education Resource Information Center (ERIC), PsycINFO, and Medline for the time periods of 2011 to May 2016. Keywords (as title and abstract words used to search for articles) were yoga and depression/depressive disorder, yoga for depression/depressive disorder, and treating depression through yoga, yielding 731 articles. There were 138 records after duplicates were removed from the search results. One hundred and thirty-eight articles were screened for intervention. Of those 138 articles, 75 articles were omitted due to not having an intervention or utilizing interventions that did not target depression (n = 42), and consisting of review and discussion articles (n = 16), or studies still in progress (n = 5). The remaining 63 articles were screened using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria for studies in this review were the following: (1) publications between 2011 and 2015, (2) publications in the English language, (3) publication of studies that measured depression or depressive symptoms as an outcome (see Table 1 for outcome measures of each study), (4) publications of studies that used yoga as an intervention that included the use of one or more of the 8 limbs, and (5) studies that used a randomized controlled design or quasi-experimental or pretest/posttest design.

Table 1.

Summary of Measurement Tools.

| Study/Year | Measurement Tools(s) |

|---|---|

| Marefat et al, 20117 | Beck’s Depression Inventory-II; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| Chan et al, 20128 | Geriatric Depression Scale; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| Muzik et al, 20129 | Beck’s Depression Inventory-II; Edinberg Postnatal Depression Scale; The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; The Maternal Fetal Attachment Scale |

| Tekur et al, 201210 | Beck’s Depression Inventory; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Numerical Rating Scale; Sit and Reach |

| Eastman-Muller et al, 201311 | Beck’s Depression Inventory; Perceived Stress Scale; Penn State Worry Questionnaire; The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire |

| Field et al, 201312 | The Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| Kinser et al, 201313 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9; Perceived Stress Scale-10; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Rumination Response Scale; Interpersonal Sensitivity and Hostility Inventory |

| Lakkireddy et al, 201314 | Zung Self-Assessment Depression Score; Zung Self-Assessment Anxiety Score |

| Lavretsky et al, 201315 | Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; Mini-Mental State Examination; Cumulative Illness Rating Scale; Medical Outcome Study SF Health Survey |

| Naveen et al, 201316 | Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor; Clinical Global Impression |

| Satyapriya et al, 201317 | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale; Pregnancy Experience Questionnaire |

| Umadevi et al, 201318 | Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale; World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF |

| Bershadsky et al, 201419 | Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale; Cortisol via cotton swabs |

| Kinser et al, 201420 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9; Perceived Stress Scale-10; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Short Form Health Survey |

| Newham et al, 201421 | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Edinberg Postnatal Depression Scale |

| Taso et al, 201622 | Profile of Mood States; Brief Fatigue Inventory |

| Battle et al, 201523 | Edinberg Postnatal Depression Scale; Treatment Response to Antidepressant Questionnaire; Credibility Expectancy Questionnaire; International Physical Activity Questionnaire; The Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire |

| Buttner et al, 201524 | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; Inventory of Depression & Anxiety Symptoms; Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| Davis et al, 201525 | Edinberg Postnatal Depression Scale; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| Doria et al, 201526 | Zung Self-Assessment Anxiety Score; Zung Self-Assessment Depression Score; Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety |

| Falsafi et al, 201527 | Beck Depression Inventory; Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; Self-Compassion Scale; Perceived Wellness Survey |

| Rao et al, 201528 | Beck Depression Inventory |

| Manincor et al, 201629 | Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21; Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; Short-Form Health Survey-12; Scale of Positive and Negative Experience; Flourishing Scale; and Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale |

The exclusion criteria were the following: (1) studies that did not measure depression or depressive symptoms as an outcome; (2) studies that were incomplete or ongoing; (3) articles that were published in a journal not indexed in any of the following databases: CINAHL, Google Scholar, ERIC, PsycINFO, and Medline; and (4) qualitative studies. Both authors evaluated the articles. After reading and reviewing the articles, there were 23 studies included in the systematic review. This is further illustrated in Figure 1. PRISMA guidelines were followed in selection of these articles for inclusion in this systematic review. Important components of each study that will be reviewed include original reference, country of the study, the name and a brief description of the intervention, duration of the intervention, age of participants, time of assessments, design and sample, and salient findings.

Figure 1.

Article selection process to locate articles for review.

Results

A total of 23 studies describing interventions that used yoga as a form of treatment for depression, meeting the inclusion criteria, were found through literature search. These studies are described sequentially, in order of their publication by year in Table 2. Studies were carried out in Australia,8,29 India,10,17,18,28 Iran,7,16 Italy,26 Taiwan,22 the United Kingdom,21 and the United States.9,11–15,19,20,23–25,27 Studies focused on the meditative aspects of yoga while others incorporated exercise and/or gentle and slow movements and awareness. Types of yoga included Antenatal,21 Anusara,22 combination of Asana and Pranayama,10,18,23 Hatha,8,13,19,20 integrated yoga,17,28 Iyengar,14 Kirtan Kriya,15,26 Mindfulness-based meditation (with yoga),9,11,27 Tai chi (with yoga),12 unspecified,7,16 and Viniyoga. 24–25,29 Hatha yoga was used most often (4 times) among the aforementioned interventions. The next most commonly used interventions were Asanas and Pranayama, the mindfulness-based meditation (with yoga), and Viniyoga, which were each used thrice.

Table 2.

Summary of Yoga-Based Interventions as a Treatment for Depression Conducted Between 2011 and May 2016 (n = 23).

| Study, Country | Year | Intervention and Description | Age | Time of Assessment | Design and Sample Size | Salient Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marefat et al,7 Iran | 2011 | Yoga group—3-60 minute yoga session per week—breathing exercises, meditation, and relaxation; physical exercises for 5 weeks Control group—Assessments only | 21-34 | Baseline; 5 weeks | Randomized, 24 narcotic drug addicts | Depression levels in the yoga group significantly decreased from before to after treatment (P = .022) Yoga exercises led to significant difference in depression level of yoga group compared to the control group in rehabilitation period (P = .048) |

| Chan et al,8 South Australia | 2012 | Yoga and exercise—Weekly: yoga safety, gentle and slow movement, breathing meditation practice; home hatha yoga; 50-minute exercise class for 6 weeks Control—Exercise weekly: 50-minute class for 6 weeks | 67.1 [SD] (15.4) 71.7 [SD] (12.7) | Baseline; 6 weeks | Randomized, 14 chronic poststroke hemiparesis patients with 6 month elapse time since stroke; completed postacute stroke rehabilitation | Both groups reported a decrease on depression from pretreatment (median = 4.0, interquartile range [IQR] = 2, 5) to posttreatment (median = 2.5, IQR = 1, 3), F(1, 12) = 5.28, P < .05 Changes in depression did significantly differ between groups (P = .749) |

| Muzik et al,9 USA | 2012 | Mindfulness yoga—3-60 minute sessions per week of Hatha yoga, breathing, visualization, and relaxation and mindfulness for 10 weeks | >18 | Quasi-experimental, 22 depressed women; 12-26 weeks pregnant taking no psychotropic medication | Depression symptoms were significantly reduced (P = .025), while mindfulness (P = .007) and maternal-fetal attachment (P = .000) significantly increased | |

| Tekur et al,10 India | 2012 | Yoga group—1 h/day of Asanas and Pranayama for 1 week, Antaranga yoga, yoga counseling, and lectures; meditation Control group—Physical therapy movements, non-yogic breathing exercises, counseling and education sessions; 1 h/day for 1 week | 18-60 | Baseline; 1 week | Randomized, 80 chronic lower back pain patients | Group × time interactions of depression was significant [F(1, 78) = 5.85, P = .018], with significant difference between groups (P < .001) Depression decreased in both groups: 47% in yoga group (P < .001, effect size [ES] = 0.96), 19% in control group (P < .001, ES 0.59) Spinal mobility improved in yoga group (50%) and control group (34.6%) NRS and SAR group × time interaction was significant |

| Eastman-Muller et al,11 USA | 2013 | Yoga-nidra—Weekly: 2 hour classes of relaxation via body sensing, breath awareness exercise; silence to integrate experience; work with conflicting emotions for 8 weeks | 18-56 | Baseline; 8 weeks | Quasi-experimental, 66 graduate and undergraduate students experiencing stress, anxiety, and worry | There was a statistical significant pre- to posttest improvement in stress, depression, and worry |

| Field et al,12 USA | 2013 | Tai chi/yoga—Weekly: 20-minute sessions of stretches and moderately aerobic exercises for 12 weeks Control—Tai chi/yoga at end of treatment period; assessments | 18-37 | Baseline; 12 weeks | Pretest/posttest, 92 clinically depressed pregnant women (with only one child) and have no medical problems; not using drugs | Tai chi/yoga showed significant group × treatment reduction in anxiety and depression (P = .01) and sleep disturbances (P = .05) |

| Kinser et al,13 USA | 2013 | Yoga—Weekly: 75-minute Hatha yoga class; daily home practices via DVD; for 8 weeks Attention-control group—Health education sessions on weekly topics; resources on weekly topics; for 8 weeks | >18 | Baseline; 2, 6, 8 weeks | Randomized, 27 women diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) | There were no significant group × time difference in depression score between the yoga and control groups; the trend in group × time (P = .083) suggests that the yoga group compared to the control group had reduced rumination score over time |

| Lakkireddy et al,14 USA | 2013 | Pre yoga—3-month no intervention observation period Yoga intervention—Twice per week: 60-minutes Iyengar yoga, pranayamas, warm-up exercises, asanas, and relaxation exercises for 12 weeks | 18-80 | Baseline; 12 weeks | Pretest/posttest, 49 atrial fibrillation patients | There was a significant improvement (P < .001) in the depression and anxiety scores in atrial fibrillation (AF) patients upon completion of the yoga intervention phase Yoga significantly reduced the amount of symptomatic AF episodes, symptomatic non-AF episodes, and asymptomatic AF episodes (P < .001) from the end of the control phase to the end of the intervention |

| Lavretsky et al,15 USA | 2013 | Kirtan Kriya yoga—Daily 12-minutes yoga relaxation breathing and meditation chanting for 8 weeks Relaxation group—Daily 12-minutes of listening to instrumental music on CD for 8 weeks | 45-91 | Baseline; 8 weeks | Randomized, 39 family dementia caregivers | There were significant improvements in depressive symptoms, mental health, and cognition (P < .05) and telomerase activity (P = .05) in the yoga group compared to the control Significant correlations were found between telomerase activity, decline in depression (r = .33; P = .05) and mental health (r = .44; P = .05) in all participants |

| Naveen et al,16 Iran | 2013 | Yoga-only—Attend daily groups for 10 days to learn yoga practices; perform yoga in center 1 h/week for the next 2 weeks; home practices; booster yoga session at end of 2 months Yoga and medication—Attend daily groups for 10 days to learn yoga practices; perform yoga in center 1 h/week for 2 weeks; home practices; antidepressants and consultation; booster yoga session at end of 2 months Medication alone—antidepressants and consultation | 18-55 | Baseline; 12 weeks | Pretest/posttest, 62 depression disorder patients attending outpatient services | Depression scores dropped significantly over time in all groups [F = 271.7; df = 1, 59; P < .001] Yoga groups had greater improvement than the medication only group [F = 5.7; df = 2, 59; P < .005] when examining group effect In the yoga-only group, there was a positive correlation between the decline in depression and a rise in brain derived neurotropic factor levels (r = .702, P = .001) |

| Satyapriya et al,17 India | 2013 | Yoga—Daily 1 hour: IAYT asana postures; pranayama, meditation for 16 weeks Control—Standard care; assessments | 20-35 | Baseline; 20th gestation; 36th gestation | Randomized, 96 women between 18th and 19th gestation (with only one child) | Depression scores decreased in yoga (30.67%, P < .001) with significant difference in groups but increased 3.57% in control Anxiety scores decreased in yoga (29.12%, P < .001) with significant difference in groups There was significant change in PEQ scores among yoga group (P < .0001) |

| Umadevi et al,18 India | 2013 | Yoga group—10 days of taught asanas and pranayama; 20 days of yoga practices on their own Control group—Assessments only | 18-60 | Baseline; 4 weeks | Randomized, 60 caregivers of patients in neurology wards who could perform yoga | A significant (P < .001) reduction in anxiety and depression scores and improved quality-of-life took place among yoga group compared to the control group |

| Bershadsky et al,19 USA | 2014 | Hatha yoga—90-minute yoga twice: early and mid pregnancy: body postures, stretching, savasana, pranayama, saliva sample at baseline and completion of yoga Control—Assessment only | >18 | Baseline; 2× early pregnancy; 2× mid-pregnancy; 2 months after delivery | Randomized, 51 perinatal depressed women between 12th and 19th gestation; did not practice yoga or relaxation techniques | Women in the yoga group reported less depressive symptoms than women in the control group in the postpartum period after controlling for antepartum depressive symptoms in early and mid-pregnancy Women who practiced yoga at least twice a week prior to first assessment reported fewer depression symptoms (M = 2.13, SD = 1.55) than women practicing yoga less (M = 4.72, SD = 2.72; t(24) = 2.51, P < .05) Cortisol levels were lower in yoga compared to control group in early pregnancy (β = −.50, SE = .23, P = .029) but did not change over time, no trajectories were observed between groups (β = −.01, SE = .20, ns) |

| Kinser et al,20 USA | 2014 | Yoga group—Weekly: 75-minute Hatha yoga; breathing and relaxation practices for 8 weeks Control group—Weekly: 75-minute health education session for 8 weeks | >18 | Baseline; 2, 4, 6, 8 weeks; 52 week | Randomized, 77 women with MDD or dysthymia diagnosis; can participate in yoga | Participants in both group showed a significant reduction in depression over time The yoga group maintained a mild level of depression 1 year after the intervention Both groups reported a significant decrease in perceived stress, state anxiety, and health-related quality of life |

| Newham et al,21 UK | 2014 | Antenatal yoga—Exercises, postures, and relaxation/breathing methods for 8 weeks Control—Treatment as usual, assessment | >18 | Baseline; 8 weeks | Randomized, 59 low-risk women in the second and early third trimester (first pregnancy and high anxiety) | Yoga sessions were effective in reducing anxiety at the beginning (37 [IQR = 30-44]) and the end of the 8-week program (32 [IQR = 25-39]) Depression scores did not change over time; however, depression scores were significantly greater among women in the control group compared to the women in the yoga group Cortisol levels increased as gestation advanced |

| Taso et al,22 Taiwan | 2014 | Anusara yoga group—60-minute yoga, 2 times a week: stretching and relaxation exercises; for 8 weeks Control group—Treatment as usual | 20-70 | Baseline; 4, 8 weeks; 4 weeks after | Randomized, 60 state I, II, III breast cancer, never performed yoga, no mental health history | There were significant time and groups for fatigue level (F = 75.49, P < .001) and influence of fatigue on daily lives (F = 51.71, P < .001) and no significant interaction effects for depression and anxiety (P > .05) |

| Battle et al,23 USA | 2015 | Prenatal yoga—Twice per week 75 minute classes; pranayama; home yoga for 10 weeks | >18 | Baseline; 10 weeks | Quasi-experimental, 34 depressed women between 12 and 26 weeks’ gestation | Women experienced a significant reduction in depression symptoms over time |

| Buttner et al,24 USA | 2015 | Yoga group—16 one-hour classes: sun salutations, balancing, twisting, and relaxation poses; 30-minute home yoga via DVD for 8 weeks WLC group—Assessments only | 18-45 | Baseline; 2, 4, 6, 8 weeks | Randomized, 57 postpartum women | Depressive symptoms decreased over time for both groups (t = −10.17; df = 55; P < .0001) Yoga group participants experienced a steeper linear decline in depressive symptoms (t = −2.94; df = 52; P = .005) and anxiety symptoms (t = −3.26; df = 52; P = .002) and steeper linear increase in well-being scale scores (t = 2.94; df = 52; P = .005) compared to the control group |

| Davis et al,25 USA | 2015 | Yoga—Weekly: 75-minute classes—synchronizing breath, movement and standing posture for 8 weeks Control—Treatment as usual; assessments | 18-45 | Baseline; 4, 8 weeks | Randomized, 46 women up to 28 week gestation | There was a significant improvement in depression and anxiety scores for both groups over time |

| Doria et al,26 Italy | 2015 | SKY group 1—Pre: minimum of 6 months pharmacological treatment with medication; breathing exercises SKY group 2—Pre: minimum of 6 months self-help groups; breathing exercises | 25-64 | Baseline; 3, 6 months; 15 days after | Pretest/posttest, 69 women with generalized anxiety | Anxiety scores significantly decreased (P < .001) among SKY group between baseline and 15 days after treatment Depression scores significantly decreased (P < .001) over time for SKY group |

| Falsafi et al,27 USA | 2015 | Intervention—1.5 hours per week of mindfulness, self-compassion and yoga training; materials for home practice for 8 weeks | 18-65 | Baseline; 4, 6, 8 weeks; 1 month after | Quasi-experimental, 18 uninsured patients with income below 150% of the federal poverty level; anxiety | There was statistical significant decrease in depressive symptoms scores from pre- to posttest and from pretest to follow-up (P < .05) There were also statistical improvements in anxiety (P < .05) from pre- to posttest and follow-up (P < .10); and self-compassion and general well-being from pre -to follow-up (P < .05) |

| Rao et al,28 India | 2015 | Yoga group—A set of asanas, breathing exercises, pranayama, meditation and yogic relaxation techniques with imagery for 24 weeks Control group—Supportive therapy: knowledge of disease and treatment options, express their problems, strengthen relationships, and find meaning in their lives for 24 weeks | 30-70 | Baseline; before, during, and after surgery | Randomized, 69 stage II and III breast cancer patients undergoing surgery followed by adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy | Both groups reported a reduction in their depression over time The yoga group showed a decrease in depression score before (F(57) = 6.02, P = .02), and after (F(57) = 10.90, P = .002) chemotherapy compared to the control group There was a positive significant correlation between depression scores of symptom severity and and distress during adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy |

| Manincor et al,29 Australia | 2016 | Yoga group—1 day a week Viniyoga; treatment as usual for 6 weeks Control group—Treatment as usual; assessments | >18 | Baseline; 6 weeks | Randomized, 101 depressed and anxiety patients | Statistically significant differences on reduced depression scores were found in yoga group compared to the control group (−4.30; 95% CI: −7.70, −0.01; P = .01; ES −.44); difference in reduced anxiety scores were not statistically significant (−1.91; 95% CI: −4.58, 0.76; P = .16) Statistically significant differences favoring yoga was found on total depression and anxiety scores (P = .03) |

Abbreviations: IAYT, integrated approach of yoga therapy; SKY, Surdashan Kriya yoga.

Table 3.

Risk of Bias in Included Studies.

| Study, Year | Random Sequence Generation | Allocation Concealment | Blinding of Participants and Personnel | Blinding of Outcome Assessment | Incomplete Outcome Data | Selective Reporting | Other Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marefa et al,7 2011 | Unclear | No | No | No | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Chan et al,8 2012 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | None |

| Muzik et al,9 2012 | No | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Tekur et al,10 2012 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | None |

| Eastman-Muller et al,11 2013 | No | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| Field et al,12 2013 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Kinser et al,13 2013 | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Lakkireddy et al,14 2013 | No | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| Lavretsky et al,15 2013 | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Naveen et al,162013 | No | No | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Satyapriya et al,17 2013 | Yes | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Umadevi et al,18 2013 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Bershadsky et al,19 2014 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Kinser et al,20 2014 | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Newham et al,21 2014 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear |

| Taso et al,22 2014 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | None |

| Battle et al,23 2015 | No | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| Buttner et al,24 2015 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Davis et al,25 2015 | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Doria et al,26 2015 | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| Falsafi et al,27 2015 | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| Rao et al,28 2015 | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Manincor et al,29 2016 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

Participants in the studies were all adults. Many of the studies reported that the participants were age 18 and older.8,9,13,19–23,29 Other studies reported that participants were between the ages of 18 and 45,12,17,23,24 18 and 60,10,11,16,18,26,27 18 and 80,14 20 and 35,7,17 20 and 70,22,26 30 and 70,28 and 45 and 90.15 Participants in the studies included pregnant women,9,12,17,19,21,23,25 individuals with a depression diagnosis,13,16,20,29 cancer patients,22,28 narcotic drug addicts,7 patients with poststroke hemiparesis,8 patients with lower back pain,10 college students,11 patients with atrial fibrillation,14 caregivers,15,18 postpartum women,24 anxiety,26 and low-income patients.27

Only one study included patients with a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, diagnosis of a depressive disorder.26 Fourteen studies included adults with elevated levels of depression diagnosed by Beck’s Depression Inventory-II,7 Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale,9 Structural Clinical Interview for Depression,12,15,25 MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview,13,20 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,16 Patient Health Questionnaire,23,24 Depression Anxiety Stress Scale,29 and a clinician.10,14,27 Five studies included patients with self-report of depression.8,19,21–22,28 In 2 studies, the depression criteria were unclear.17–18

Studies used pretest/posttest,12,14,16,26 quasi-experimental,9,11,23,27 and randomized controlled trials.7,8,10,13,15,17–22,24,25,28,29 Sample sizes were small, ranging in size from 14 to 136 patients. Intervention periods ranged in length from 1 week to 24 weeks. One study did not specify its length, but it can possibly be concluded that it took place for up to 32 weeks. Among the yoga intervention, participants were encouraged or required to attend yoga classes anywhere from once a week to daily for 1 or more weeks. The time asked to practice yoga ranged from 12 minutes to 90 minutes. Majority of the studies encouraged participants to practice yoga once a week. The longest duration included 1 hour daily yoga per 16 weeks. Only 4 studies10,17,22,25 reported the use of power analysis. This is a limitation of the studies utilizing yoga to study its effect on depression.

There were 5 studies that did not have a comparison or control group.9,11,14,23,27 Ten studies compared yoga to no specific treatment, including assessment(s) only7,12,18,19,24 or standard care.17,21,22,25,29 Two studies compared yoga to health education.13,20 One study each compared yoga to aerobic exercise,8 physical therapy,10 instrumental music,15 pharmacological treatment,16 self-help,26 and social support group.28

Studies assessed severity of depression using the Beck’s Depression Inventory,10,11,27,28 Beck’s Depression Inventory-II,7,9 the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression,15,16,24,26 the Geriatric Depression Scale,8 the Centers for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale,12,19 Patient Health Questionnaire,13,20,24 the Zung Depression Self Rating Scale,14,26 Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale,17,18 the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale,23,25 Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms,24 or Depression Anxiety Stress Scale.29 The severity of anxiety or stress was assessed using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory,7–8,10,12,13,17,20,25 Perceived Stress Scale,11,13,20 the Zung Assessment Anxiety Self Rating Scale,14,26 the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety,26,27 Pregnancy Experience Questionnaire,17 and the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale.29 Health-related quality of life was assessed using the Medical Outcome Study Health Survey,15 World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF,18 and the Short Form Health Survey.20,29 Mindfulness was assessed using the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire9,11,23 and the Self-Compassion Scale.27 Maternal-fetal attachment during pregnancy was assessed via the Maternal Fetal Attachment Scale.9 Pain or illness burden was assessed using the Numerical Rating Scale10; hamstring and lower back flexibility were measured using the Sit and Reach.10 Worry was assessed using the Penn State Worry Questionnaire.11 Rumination or negative thinking was assessed via the Rumination Response Scale.13,20 Interpersonal factors were assessed using the Interpersonal Sensitivity and Hostility Inventory13,15 and the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale.29 Fatigue was assessed using the Brief Fatigue Inventory.22 Wellness was assessed using the Perceived Wellness Survey.27

Study quality was assessed using the Cochrane guidelines for systematic reviews. Results from the risk of bias assessment showed that 4 studies had low risk of bias,8,10,21,22 5 studies had high risk of bias,9,11,14,23,26,27 and 14 studies had unclear risk of bias.7,12,13,15–20,24,25,28,29 Risk of selection bias was generally low as 11 studies reported adequate random sequence generation8,10,13,15,17,18,20–22,25,29; and 7 studies reported adequate allocation concealment.8,10,18,21,22,28,29 Risk for performance bias was high as only one study reported blinding of participants and personnel;10 and 2 studies reported blinding of outcome assessment.8,10 Incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed in only 6 studies.7,8,10,12,22,24 Risk for selective reporting is unclear as only 3 studies had adequate reporting.10,21,22 Five articles were nonrandomization studies, thus have selection bias.11,14,25–27

Yoga as a complementary form of therapy and treatment was found to be beneficial in the majority (n = 14) of the interventions.7,9–12,14,15,17–19,23,26,27,29 While in 6 interventions both groups (yoga and control) showed improvement,8,16,20,24,25,28 and there were no significant changes in 3 interventions.13,21,22 One of the studies that reported no significant change concluded that while yoga did not reduce depression, it prevented an increase in depressive symptoms.21 Significant effects of yoga on depression were observed in the yoga group,11 both groups,13,25 and yoga group compared to the control group.17 In one study, the yoga group reported less depressive symptoms during the early pregnancy and postpartum periods.19 No significant effect was found in one study that examined yoga intervention in reducing depressive symptoms among breast cancer patients.22

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to examine the effectiveness of yoga as an alternative treatment or complementary form of therapy for depression and depressive symptoms. In our search of the English-language peer-reviewed literature from 4 databases, 23 interventions between 2011 and May 2016 were evaluated. This number suggests that over the past 5 years, there was continued interest in examining the effectiveness of yoga practices for managing depression and reducing depressive symptoms. This literature review provides positive findings of yoga interventions in reducing depression symptoms. Per this review, individuals with elevated depression levels and/or medical conditions benefited from yoga treatment. Results also revealed that depression symptoms improved among caregivers.

Our review found that yoga was effective in reducing depressive symptoms in pregnant women,9,12,17,19,21,23,25 among patients experiencing lower back pain,10 among patients with atrial fibrillation,14 among persons with poststroke hemiparesis,8 and addicts.7 While most of the interventions found yoga to be effective in treating depressive symptoms, 3 studies, stroke patients,8 pregnant patients,21 and breast cancer patients,22 found no significant impact. In this review, there were similar studies that reported a positive effect of yoga and depression, which differ from some of the nonsignificant results. There were 2 studies examining the effect of yoga in reducing depression symptoms; while one study did not find a significant impact of depression among breast cancer patients,22 the study did find a positive impact. This is also true for other studies finding a positive impact of yoga in decreasing depressive symptoms in pregnant women9,12,17,19,23,25 and postpartum depression.18 Some factors that could affect the results are the difference in geological locations, difference in the styles of yoga used, sample characteristics, and duration of yoga intervention. This warrants more research on the effect of yoga for specific population groups such as depressed patients with breast cancer to understand the factors that are associated with the mixed results.

Various yoga methods were used in these studies with Hatha yoga 8,13,19–20 being the most, followed by asana pranayama,10,18,23 and the Western adaptation of yoga, mindfulness meditation 9,11,17 and Viniyoga.24,25,29 It was not evident from the review that any one type/school of yoga was better than the other. They all reported reductions in depressive symptoms among participants in the yoga groups. However, Hatha yoga has been identified as one of the most commonly used form of yoga in the United States.30

Regardless of the length of the intervention, the interventions proved to be efficacious. For example, the shortest yoga intervention with depressed patients with chronic back pain10 showed positive results. These findings suggest that brief yoga treatment or therapy can be effective in reducing depressive symptoms. The longest intervention19 followed women through their pregnancy to 2 months postpregnancy. The pregnant women showed a reduction in depressive symptoms. These findings suggest that yoga interventions can have a long-term positive effect on depressive symptoms. Seven studies implemented some form of follow-up with participants after the intervention;11,13,17–20,22,27,28 only in 6 studies did effects persist.11,13,17,19,22,25

There were many commonalities in the articles reviewed. Per this current review of literature, common interest of yoga and depression took place with pregnant and postpartum women (n = 7), patients diagnosed with a depressive disorder (n = 4), caregivers (n = 2), and breast cancer patient (n = 2). They reported positive impacts of yoga in treating depression in patients. This information gives value to the positive effect yoga has in reducing depression among these groups. Most of the studies examined the effect of yoga on depressed patients with medical (n = 13) and mental health conditions (n = 6). Two studies examined the impact of yoga on reducing depression among caregivers.15,18 As both reported positive effects, more research is needed for caregivers of medical and mental health patients. Another commonality of the interventions involved yoga practices among the adult population. Only one study11 examined the effectiveness of yoga for treating depression, stress, and worry among college students. As yoga was found to reduce depressive symptoms in college students, more studies are needed to add to the body of knowledge with this population.

These findings provide support for mind-body interventions such as yoga for improving depression symptoms. While mind-body interventions may not be more effective than existing evidence-based treatments for depression,31 there is one great benefit. Yoga can serve as alternative to many individuals who may not participate in psychotherapy or antidepressants due to factors such as side effects, unmet needs, lack of access/resource, and personal choice.

The results of this review are in line with those of prior systematic reviews on yoga for depression. Two systematic reviews found evidence of the effectiveness of yoga for reducing depression;32,33 another more recent review article reported that yoga was better than usual care, relaxation techniques, or aerobic exercises in reducing depressive symptoms.34

Limitations of the Interventions

There were some limitations of the interventions. Majority of the studies utilized a small sample, which limits the power of statistical analysis. Many of the studies were randomized controlled trials; however, there were also other designs used. Next, majority of the studies examined the short-term effects of yoga to treat depression. Studies examining the long-term effectiveness of yoga for depression are limited and more studies in this area are warranted. While the literature reports findings on various population and study area, it limits the variety of literature of the effect of yoga on depression regarding other populations and study areas. These findings support Mehta and Sharma’s6 suggestion for more studies that examine the effect of yoga on depression within youth and among various ethnicity groups, cultures, sex, and occupation. Finally, none of the interventions utilized any behavioral theory to help participants adhere to the practice of yoga. The use of cognitive and behavioral theories and strategies are suggested because they are used as a form of treatment for reducing depression in patients with depressive disorder.

Limitations of This Review

There were some limitations of this review. This search only consisted of restricted databases and there are other databases that were not included in this research. Grey literature was not searched in this study. Only articles in the English language were included; articles in other languages were not included. There could have been publication bias as many of the studies used in this review reported positive findings and many articles with negative results may have been rejected. Quality of studies was not assessed. Finally, studies that measured depression or depressive symptoms as an outcome measure were used, omitting articles that measured depression but not as an outcome measure.

Implications for Practice

While literature on yoga intervention for depression continues to lengthen, there continues to be a growing need for more studies of yoga practices for treating depression and depressive symptoms. Based on the review, the following recommendations for future studies are made. More studies are needed on yoga for reducing depression and depressive symptoms in various comorbid mental health and physical health conditions and for caregivers. Such research should be conducted on studies of yoga for depression among groups such as race and ethnicity, cultures, youth and young adults, and socioeconomic status in various geographical location and conditions. For example, more studies are needed on yoga for reducing depression symptoms among the various depressive disorders and other mental health illnesses (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder) and medical conditions (eg, breast cancer patients) as this review reports limited research and mixed results on these areas This will result in more knowledge in understanding the direct impact of yoga for depressive symptoms among various groups of individuals.

While there are many aspects of yoga, there is also a need to examine more of the styles and specific aspects of yoga on depression. These will merit the full or exact understanding of the impact that yoga has on depression. Finally, yoga interventions should utilize behavioral theories/techniques such as social cognitive theory,35 multi-theory model of health behavior change,36,37 and others in designing and evaluating the interventions. This is imperative as psychotherapy techniques are used in managing depressive symptoms and stress management.

Conclusions

Yoga is a fairly new treatment or practice utilized for more than mind-body fitness in the West. In fact, yoga is being used more and more as an alternative form of treatment for improving many conditions. One way that yoga is used is in individuals with depressive symptoms. Recently, researchers have examined the benefits and effectiveness of depression for managing depressive symptoms. This review reveals that yoga provides limited evidence that a restricted number of studies (those published between 2011 and 2015) may influence depression outcomes in various populations. Many more interventions on the subject area are needed to continue to learn and understand fully the impact of yoga and depression.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Center for University Scholars, Jackson State University, for awarding a graduate assistantship in order to complete this project.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: MS conceptualized the study, both MS and LB retrieved the articles, LB prepared the first draft, and MS worked on the final draft and submission.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Only graduate assistantship support was provided by the Center for University Scholars, Jackson State University.

Ethical Approval: As human subjects were not involved in this study, ethical approval was not required.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Depression. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/. Accessed June 6, 2016.

- 2. National Alliance of Mental Illness. Depression. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Depression. Accessed June 16, 2017.

- 3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). 5th ed Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Institute of Mental Health. Depression basics. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression/index.shtml#pub5. Accessed June 6, 2016.

- 5. Woodard C. Exploring the therapeutic effects of yoga and its ability to increase quality of life. Int J Yoga. 2011;4(2):49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mehta P, Sharma M. Yoga and complementary therapy for clinical depression. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2010;15:156–170. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marefat M, Peymanzad H, Alikhajeh Y. The study of the effects of yoga exercises on addicts’ depression and anxiety in rehabilitation period. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2011;30:1494–1498. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chan W, Immink MA, Hillier S. Yoga and exercise for symptoms of depression and anxiety in people with poststroke disability: a randomized, controlled pilot trial. Altern Ther Health Med. 2012;18(3):34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Muzik M, Hamilton SE, Lisa Rosenblum K, Waxler E, Hadi Z. Mindfulness yoga during pregnancy for psychiatrically at-risk women: preliminary results from a pilot feasibility study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2012;18:235–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tekur P, Nagarathna R, Chametcha S, Hankey A, Nagendra HR. A comprehensive yoga programs improves pain, anxiety and depression in chronic low back pain patients more than exercise: an RCT. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2012;20:107–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eastman-Mueller H, Wilson T, Jung A, Kimura A, Tarrant J. iRest yoga-nidra on the college campus: changes in stress, depression, worry, and mindfulness. Int J Yoga Ther. 2013;23(2):15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Field T, Diego M, Delgado J, Medina L. Tai chi/yoga reduces prenatal depression, anxiety and sleep disturbances. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19:6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kinser PA, Bourguignon C, Whaley D, Hauenstein E, Taylor AG. Feasibility, acceptability, and effects of gentle hatha yoga for women with major depression: findings from a randomized controlled mixed-methods study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;27:137–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lakkireddy D, Atkins D, Pillarisetti J, et al. Effect of yoga on arrhythmia burden, anxiety, depression, and quality of life in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1177–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lavretsky H, Epel ES, Siddarth P, et al. A pilot study of yogic meditation for family dementia caregivers with depressive symptoms: effects of mental health, cognition, and telomerase activity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28:57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Naveen GH, Thirthalli J, Rao MG, Varamball S, Christopher R, Gangadhar BN. Positive therapeutic and neurotropic effects of yoga in depression: a comparative study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:400–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Satyapriya M, Nagarathna R, Padmalatha V, Nagendra HR. Effect of integrated yoga on anxiety, depression, & well-being in normal pregnancy. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19:230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Umadevi P, Ramachandra S, Varambally S, Phillip M, et al. Effect of yoga therapy on anxiety and depressive symptoms and quality-of-life among caregivers of in-patients with neurological disorders at a tertiary care center in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:385–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bershadsky S, Trumpfheller L, Kimble HB, Pipaloff D. The effect of prenatal Hatha yoga on affect, cortisol and depressive symptoms. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2014;20:106–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kinser PA, Elswick RK, Kornstein S. Potential long-term effects of a mind-body intervention for women with major depression disorder: sustained mental health improvements with a pilot yoga intervention. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2014;28:377–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Newham JJ, Wittkowski A, Hurley J, Aplin JD, Westwood M. Effect of antenatal yoga on maternal anxiety and depression: a randomized control trial. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31:631–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Taso CJ, Lin HS, Lin WL, Chen SM, Huang WT, Chen SW. The effect of yoga exercise on improving depression, anxiety, and fatigue in women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Nurs Res. 2014;22:155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Battle CL, Uebelacker LA, Magee SR, Sutton KA, Miller IW. Potential for prenatal yoga to serve as an intervention to treat depression during pregnancy. Womens Health Issues. 2015;25:134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buttner MM, Brock RL, O’Hara MW, Stuart S. Efficacy of yoga for depressed postpartum women: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2015;21:94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Davis K, Goodman SH, Leiferman J, Taylor M, Dimidjian S. A randomized controlled trial of yoga for pregnant women with symptoms of depression and anxiety. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2015;21:166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Doria S, de Vuono A, Sanlorenzo R, Irtelli F, Mencacci C. Anti-anxiety efficacy of Sudarshan kriya yoga in general anxiety disorder: a multicomponent, yoga based, breath intervention program for patients suffering from generalized anxiety disorder with or without comorbidities. J Affect Disord. 2015;15:310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Falsafi N, Leopard LL. Use of mindfulness, self-compassion, and yoga practices with low-income and/or uninsured patients with depression and/or anxiety. J Holist Nurs. 2015;33:289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rao RM, Raghuram N, Nagendra HR, et al. Effects of integrated yoga program on self-reported depression scores in breast cancer patients undergoing conventional treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:174–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Manincor M, Bensoussan A, Smith CA, et al. Individualized yoga for reducing depression and anxiety, and improving well-being: a randomized controlled trial. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:816–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burley M. Hatha-Yoga: Its Context, Theory and Practice. Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khoury B, Lecomte T, Fortin G, et al. Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:763–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J, Dobos G. Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:1068–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pascoe MC, Bauer I. A systematic review of randomized control trials on the effects of yoga on stress measures and mood. J Psychiatry Res. 2015;68:270–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ubelacker LA, Broughton MK. Yoga for depression and anxiety: a review of published research and implications for healthcare providers. R I Med J (2013). 2016;99(3):20–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. 1st ed New York, NY: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sharma M. Multi-theory model (MTM) for health behavior change. WebmedCentral Behaviour. 2015;6(9):WMC004982. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sharma M, Romas JA. Theoretical Foundations of Health Education and Health Promotion. 3rd ed Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett; 2017. [Google Scholar]