Abstract

Age-related changes in T-cell function are associated with a loss of influenza vaccine efficacy in older adults. Both antibody and cell-mediated immunity plays a prominent role in protecting older adults, particularly against the serious complications of influenza. High dose (HD) influenza vaccines induce higher antibody titers in older adults compared to standard dose (SD) vaccines, yet its impact on T-cell memory is not clear.

The aim of this study was to compare the antibody and T-cell responses in older adults randomized to receive HD or SD influenza vaccine as well as determine whether cytomegalovirus (CMV) serostatus affects the response to vaccination, and identify differences in the response to vaccination in those older adults who subsequently have an influenza infection.

Older adults (≥ 65 years) were enrolled (n = 106) and randomized to receive SD or HD influenza vaccine. Blood was collected pre-vaccination, followed by 4, 10 and 20 weeks post-vaccination. Serum antibody titers, as well as levels of inducible granzyme B (iGrB) and cytokines were measured in PBMCs challenged ex vivo with live influenza virus. Surveillance conducted during the influenza season identified those with laboratory confirmed influenza illness or infection.

HD influenza vaccination induced a high antibody titer and IL-10 response, and a short-lived increase in Th1 responses (IFN-γ and iGrB) compared to SD vaccination in PBMCs challenged ex vivo with live influenza virus. Of the older adults who became infected with influenza, a high IL-10 and iGrB response in virus-challenged cells was observed post-infection (week 10 to 20), as well as IFN-γ and TNF-α at week 20. Additionally, CMV seropositive older adults had an impaired iGrB response to influenza virus-challenge, regardless of vaccine dose.

This study illustrates that HD influenza vaccines have little impact on the development of functional T-cell memory in older adults. Furthermore, poor outcomes of influenza infection in older adults may be due to a strong IL-10 response to influenza following vaccination, and persistent CMV infection.

Keywords: Influenza, Vaccination, Older Adult, Cytomegalovirus, Antibody, Cytokine

1. Introduction

Older adults are at increased risk of death and complications due to influenza infection (Simonsen et al., 2000; Schanzer et al., 2007), accounting for 90% of influenza-related deaths (Thompson et al., 2010). While vaccinations rates have increased over the years (Gionet, 2015), hospitalizations rates remain unchanged (Thompson et al., 2004).

One of the causes of increased influenza associated morbidity and mortality in older adults is decreasing vaccine effectiveness with age (Goodwin et al., 2006; Simonsen et al., 2007). The current influenza vaccine strategy hinges on inducing an antibody response, but has poor efficacy in older adults. Age-related changes in both B and T-cells are associated with a decline in the antibody response to vaccination (Goronzy et al., 2001; Saurwein-Teissl et al., 2002; Frasca et al., 2010; Frasca et al., 2016). Furthermore, influenza antibody titers have been shown to be a poor correlate of protection in older adults (McElhaney et al., 2006; McElhaney et al., 2009). Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses have been identified to be protective against influenza disease (La Gruta and Turner, 2014), thus underlining the importance of including measures of the cellular immune response in the assessment of influenza vaccine efficacy (Effros, 2007). Specifically, granzyme B (GrB) activity and IFN-γ:IL-10 ratios in influenza virus-challenged PBMCs have been found to correlate with protection against influenza in older adults (McElhaney et al., 2006; McElhaney et al., 2009; Shahid et al., 2010) and could be useful measures when evaluating vaccine efficacy.

The majority of older adults are seropositive for cytomegalovirus (CMV) (Staras et al., 2006) which may be a confounding factor in evaluating the immune response to influenza vaccination (Frasca et al., 2015; Furman et al., 2015; McElhaney et al., 2015; Haq et al., 2016). Persistent CMV infection has been shown to be a major driver of terminal differentiation of CD8+ T-cells (Derhovanessian et al., 2009; McElhaney et al., 2009). These terminally differentiated CD8+ T-cells express and release the cytolytic mediator, GrB, in the absence of perforin in both the resting and activated state (Zhou and McElhaney, 2011), and can contribute to toxicity in the extracellular space (McElhaney et al., 2012). The presence of high levels of baseline GrB (bGrB) in the resting state of unstimulated T-cells hinders the inducible GrB (iGrB) response to ex vivo influenza challenge (McElhaney et al., 2012; Haq et al., 2016) and may result in a compromised response to infection.

Previous studies comparing high dose (HD) and standard dose (SD) influenza vaccine formulations in older adults found significantly higher antibody titers in those receiving HD vaccinations (Couch et al., 2007; Falsey et al., 2009; DiazGranados et al., 2013; DiazGranados et al., 2014) but the impact of vaccine dose on cellular immune response requires further investigation.

Here we present the results of a randomized study comparing SD and HD influenza vaccines in older adults using longitudinal sampling and an ex vivo infection model. Changes in cell-mediated immune responses pre- and post-vaccination were measured to determine the impact of vaccine dose, influenza infection, and CMV seropositivity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Population

Ethics approval was obtained from local ethics committees: University of Connecticut Health Centre and Health Sciences North (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02297542). Older adults (≥ 65 years of age, n = 106) and young adults (20–40 years of age, n = 19) were recruited through the UConn Center on Aging Recruitment Core (UCARC) and the Health Sciences North Research Institute. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The inclusion criteria for this study required older adults to have received an influenza vaccination in the previous influenza season. Exclusion criteria included: (a) immunosuppressive disorders or medications (including oral prednisone in doses > 10 mg daily); (b) inability to be vaccinated due to a previous significant adverse reaction to influenza vaccine, eggs, latex, or thimerosol, or refusal of vaccination; (c) recipients of influenza vaccination from a community-based program for the approaching influenza season; and (d) pregnancy at week 0 (pre-vaccination).

2.2. Vaccination

Older adults were randomized to receive either the trivalent, split-virus Sanofi Pasteur Fluzone SD vaccine (15 μg of Hemagglutinin (HA) per strain) (n = 53) or Fluzone HD vaccine (60 μg of HA per strain) (n = 53). All young adults received the Fluzone SD vaccine. This study was conducted over the 2014/2015 flu season. The trivalent influenza vaccine in this season consisted of: A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)-like virus, A/Texas/50/2012 (H3N2)-like virus and B/Massachusetts/2/2012-like virus.

2.3. Sample collection

Whole blood samples were collected pre-vaccination (week 0) and also at 4, 10 and 20 weeks post-vaccination. PBMCs were isolated from heparinized blood samples using Ficoll-Plaque Plus (GE Healthcare) gradient purification and transferred to liquid nitrogen for storage. Plasma and serum samples were collected and stored at −80°C.

2.4. Frailty measures

To measure frailty, two measures were used. The Fried Model was used to measure the Frailty phenotype based on the number of deficits: unintended weight loss, tiredness, weak grip strength, slow walking speed, and physical inactivity (Fried et al., 2001). Scores were categorized as follows: 3–5, frail; 1–2, pre-frail; and 0, non-frail. The Frailty Index was determined by assessing 40 validated deficits (McNeil et al., 2012), calculating the sum of deficits then divided by the total deficits considered (Rockwood and Mitnitski, 2011). Individuals with a low Frailty Index (< 0.05) were classified as non-frail, whereas those with an index value of > 0.4 were classified as frail; those with intermediate values were considered to be pre-frail.

2.5. Influenza surveillance

Participants received weekly phone calls during the influenza season and were requested to report any influenza-like illness (ILI) or acute respiratory infection (ARI). ILI was defined by the presence of two respiratory symptoms (cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, and nasal stuffiness) or 1 respiratory and 1 systemic symptom (headache, malaise, oral temperature > 37°C or fever and muscle ache). When reported symptoms met the ILI criteria and were within 5 days of symptom onset, a nasal swab was collected. A laboratory diagnosis of influenza illness was confirmed by the detection of influenza virus by PCR assay of the nasal swab or a 4-fold or greater rise in the antibody titer from pre-vaccination to 4-week post-vaccination.

2.6. Influenza serological analysis

Hemagglutinin-inhibition (HAI) antibody titer assays for A/California/7/2009 (H1N1), A/Texas/50/2013 (H3N2), and B/Massachusetts/2/2012 virus strains were performed using previously described standard methodologies (Webster et al., 2002; Lancaster and Febbraio, 2014).

2.7. CMV serology

The CMV serostatus was determined by testing serum using a CMV IgG ELISA kit (Genesis Diagnostics Inc., Cambridgeshire, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.8. Cell stimulation

To measure cellular immune responses, PBMCs were stimulated with live influenza virus as previously described (McElhaney and Gentleman, 2015). Briefly, PBMCs were challenged ex vivo with live influenza virus A/Victoria/3/75 (H3N2) or B/Lee/40 (Charles River). Influenza A/H1N1 stimulation was not performed. After a 20-h incubation at 37°C, PBMC lysates and supernatants were collected and frozen at −80°C. Viral strains matching those in the 2014–2015 influenza vaccine were not used as our studies focus on investigating T-cell response, which are primarily targeted against conserved internal or non-structural proteins (Thomas et al., 2006). Further, we have a consistent commercially available source of sucrose gradient-purified influenza virus, which we have shown stimulates similar T-cell responses when compared to seasonal influenza strains (unpublished data).

2.9. Granzyme B assay

GrB activity was measured based on cleavage of the peptide substrate, IEPDpNA (EMD Millipore), which causes a colorimetric change with the release of p-nitroaline (pNA), and is measured as enzyme units (U). GrB activity is adjusted by the total protein content in the cell lysate using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Pierce, ThermoFisher Scientific), and reported as U/mg of protein (McElhaney and Gentleman, 2015). bGrB was determined by measuring GrB activity in unstimulated T-cells (cells isolated using StemCell Technologies EasySep T-cell negative selection kit). iGrB ratio levels were calculated as iGrB = (GrB in virus stimulated PBMC lysates)/(bGrB). iGrB levels were determined for both A/Victoria/3/75 (H3N2) and B/Lee/40 challenged PBMCs.

2.10. Multiplex cytokine assay

MILLIPLEX MAP (Milipore) was used to measure cytokine levels (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-15, IL-22) in the supernatants of PBMC cultures (A/Victoria/3/75 (H3N2)-stimulated) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentrations of cytokines were measured using the Luminex Instrumentation system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to standard curves and analyzed using Bioplex Manager software. Minimum levels of detection (MLD) for each of the cytokines assayed are: IFN-γ [1.8 pg/ml], TNF-α [0.9 pg/ml], IL-1β [2.1 pg/ml], IL-6 [1.7 pg/ml], IL-10 [0.3 pg/ml], IL-15 [2.7 pg/ml], IL-22 [0.021 ng/ml]. Cytokine levels below the MLD were assigned a value of one-half of the minimum level of detection for the analysis. Samples with undetectable cytokine levels were entered at half of the MLD. If > 1/3 of data points in the dataset fell below the MLD for a particular cytokine, the analysis was not performed.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Normal distribution of the data was tested using the D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test. Analysis of GrB was performed on log10 transformed data: the t-test was used for comparison between groups at a single time point, paired t-tests for within-group comparisons between time points, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for multiple comparisons. For the analysis of antibody titers (log10 transformed) and cytokines: the Mann-Whitney test was used for between-group comparisons at a single time point, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test was used for within-group comparisons between time points. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to determine associations between variables. The Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables as appropriate. The associations between age, gender, CMV seropositivity, vaccine dose, GrB levels, cytokine levels, and other clinical factors in response to influenza vaccination and infection were investigated using multiple linear logistic regression models. Analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 and SPSS version 14 (SPSS inc.).

Due to the enhanced response to ex vivo live virus-challenge in PBMCs following natural influenza infection (Shahid et al., 2010), data from Flu+ subjects obtained post infection were excluded from the analysis of vaccine dose and CMV serostatus.

This study was not sufficiently powered for a comparison of HAI titers between vaccine groups, with a reported coefficient of variation of 138% (Wood et al., 1994; Stephenson et al., 2007), but did allow for the analysis of trends. This study was appropriately powered for analysis of GrB (13 subjects per group) and cytokines (33 subjects per group) to detect a 25% difference between groups (95% CI, power 0.8) (Gijzen et al., 2010).

3. Results

3.1. Impact of influenza vaccine dose in older adults

3.1.1. Cohort statistics

One hundred and six older adults were enrolled and vaccinated in the study at the beginning of the 2014/2015 flu season. Demographic data was comparable between the vaccine groups: SD (n = 53) and HD (n = 53) (Table 1). Each group had a similar mean age (± standard deviation) of 75 years ± 7.5 (SD) and 75 years ± 7.8 (HD), along with other cohort characteristics including CMV status (~55% CMV+), sex (~30% male), medical conditions and medication usage. For the measures of frailty, the Frailty Index was similar between groups (SD, 0.10 (± 0.08) and HD, 0.11 (± 0.07), (p = 0.37)), although frailty by the Fried criteria was lower in the SD group (median (IQR): SD, 1(1); HD, 2(1); p = 0.05).

Table 1.

Summary of clinical data for older adults by vaccine dosage

| Parameter | High Dose (n=53) | Standard Dose (n=53) | Statistics (p Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (Std Dev) | 75 (7.8) | 75 (7.5) | 0.87 |

| Male, n (%) | 17 (32.1) | 18 (34.0) | 1.00 |

| Frailty (Fried Model), median (IQR) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.05 |

| Frailty Index, mean, (Std Dev) | 0.11 (0.07) | 0.10 (0.08) | 0.37 |

| BMI, mean (Std Dev) | 28 (5.3) | 28 (4.3) | 0.41 |

| CMV Positive, n (%) | 31( 58.5) | 29 (54.7) | 0.84 |

| Influenza Positive, n (%) | 3 (5.7) | 4 (7.5) | 1.00 |

| Medical Conditions: | |||

| Endocrine, n (%) | 10 (18.9) | 9 (17.0) | 1.00 |

| Cardiac, n (%) | 19 (35.8) | 13 (24.5) | 0.84 |

| Vascular, n (%) | 42 (79.2) | 37 (69.8) | 0.37 |

| Pulmonary, n (%) | 7 (13.2) | 4 (7.5) | 0.35 |

| Renal, n (%) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Neuromuscular, n (%) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Liver, n (%) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Gastrointestinal, n (%) | 17 (32.1) | 19 (35.8) | 0.84 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 11 (20.8) | 17 (32.1) | 0.27 |

| Rheumatological, n (%) | 2 (3.8) | 3 (5.7) | 1.00 |

| Mental, n (%) | 5 (9.4) | 5 (9.4) | 1.00 |

| Medications: | |||

| ACE Inhibitor, n (%) | 13 (24.5) | 15 (28.3) | 0.83 |

| Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonist, n (%) | 11 (20.8) | 12 (22.6) | 1.00 |

| B-Blocker (%) | 17 (32.1) | 13 (24.5) | 0.52 |

| Calcium Chanel Blocker, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 1.00 |

| Glucosamine, n (%) | 2 (3.8) | 1 (1.9) | 1.00 |

| NSAID, n (%) | 19 (35.8) | 18 (34.0) | 1.00 |

| Statin, n (%) | 27 (50.9) | 21 (39.6) | 0.33 |

Std Dev, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; CMV, cytomegalovirus; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; NDAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

3.1.2. HD vaccination induces higher and enduring influenza titers in older adults

Previous studies comparing HD and SD vaccines in older adults have found significantly higher antibody titers in those receiving HD than SD vaccine at 28 days post-vaccination for all 3 influenza strains (Falsey et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2011; DiazGranados et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2016). In this study, longitudinal sampling also supported a comparison of the duration of the antibody response between the two groups over the course of the influenza season (early January to March 2015, corresponding to 10 and 20 weeks post-vaccination).

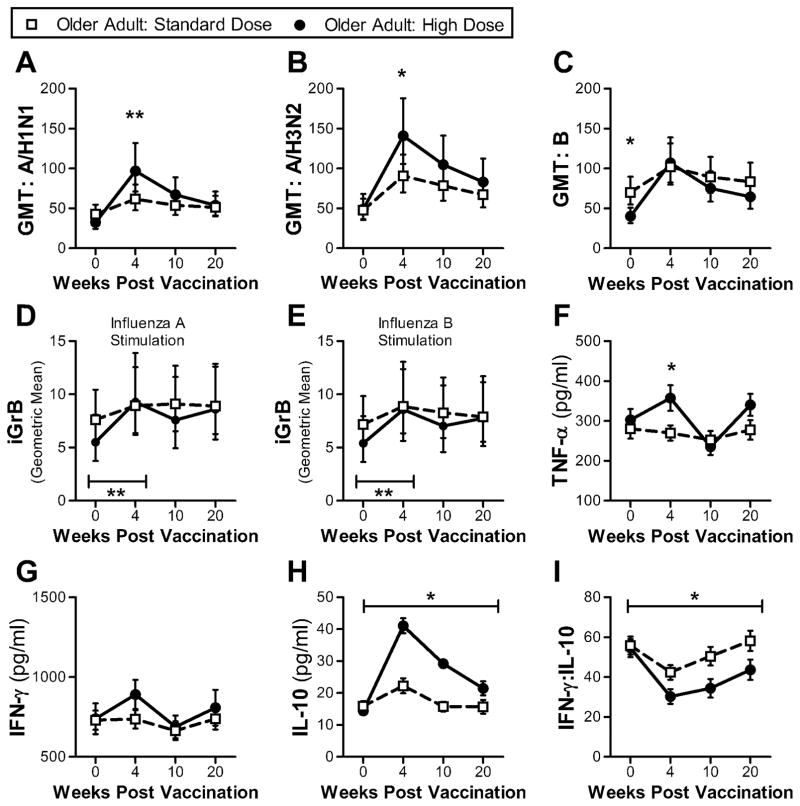

Consistent with previous observations, the geometric mean titer (GMT) was higher in the HD compared to the SD group at week 4 post-vaccination for both influenza A strains (Fig. 1a–b). Although the influenza B pre-vaccination GMT was higher in the SD than in the HD group, the fold increase in antibody titers in response to vaccination for influenza B was greater in the HD compared to the SD group (Table S2a). HD vaccination also improved the duration of the antibody response (up to week 20) compared to SD vaccination, but only for the influenza A/H1N1 and B strains (Table S2a). While the HD vaccine induced a greater antibody response, there was no difference in seroprotection rates (titer ≥ 40) between the vaccine groups at week 4, for each of the three influenza strains. It should be noted that other studies have reported greater seroconversion rates in HD vaccine recipients (Falsey et al., 2009; DiazGranados et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2016). Although the difference in pre-vaccination titers between the young and older adults was large (Fig. S1), the fold increase in antibody titers was similar in older and younger adults receiving the SD vaccine (Table S2a), suggesting pre-vaccination titers play a greater role than age in the antibody response to influenza vaccination, consistent with our previous observations (Höpping et al., 2016).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of antibody and cellular responses between older adults receiving HD influenza vaccine (n = 50) and older adults receiving SD influenza vaccine (n = 49) at 4 time points: pre-vaccination (week 0) and 4, 10 and 20 weeks post-vaccination. (a–c) Serum GMT for 3 influenza strains (A/H1N1, A/H3N2 and B). Error bars denote 95% CI. Significant differences between groups at a single time point determined using 2-sided Mann-Whitney test. Geometric mean iGrB response in PBMCs challenged with influenza A/H3N2 (d) and B (e). Significant difference between groups determined by ANCOVA. Error bars denote 95% CI. (f–h) Mean cytokine levels (TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-10) in supernatants of ex vivo live influenza virus-challenged PBMCs (A/H3N2). Error bars denote SEM. Significant differences between groups at a single time point determined using 2-sided Mann-Whitney test. Significance between groups across the 4 time points was determined by ANOVA. (i) Mean IFN-γ:IL-10 ratio in supernatants of ex vivo live influenza virus-challenged PBMCs (A/H3N2). Error bars denote SEM. Significant differences between groups at a single time point determined using 2-sided Mann-Whitney test. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01.

The data presented here shows that HD vaccination induces higher and longer lasting antibody responses, but may not necessarily improve seroprotection rates compared to SD vaccines.

3.1.3. Greater iGrB response in HD vaccine recipients to live influenza virus challenge, but only between 4 and 10 weeks post-vaccination

GrB responses play an important role in the killing of influenza-infected cells (Johnson et al., 2003). To determine the impact of vaccination on iGrB responses, we measured its activity in live virus-challenged PBMCs. While both vaccines induced significantly higher iGrB responses post-vaccination (week 0 to week 4: paired t-test, p ≤ 0.001), iGrB responses in HD recipients were higher than the SD group at week 4 after adjusting for pre-vaccination iGrB levels (ANCOVA: A/H3N2, p = 0.004; influenza B, p = 0.02) but not at the later time points (Fig. 1d, e). In young adults, the iGrB response to virus-challenge was not significantly improved by vaccination (paired t-test A/H3N2, p = 0.1; B, p = 0.07). It should also be noted that comparable iGrB responses to vaccination were found in PBMCs challenged with influenza A/H3N2 and B viruses. The results presented here suggest that HD compared to SD vaccination results in a significant increase in the iGrB response to live virus-challenge, but this response was not maintained, likely due to a decline in effector CD8+ T-cells by 10 weeks post-vaccination as previously reported (Zhou and McElhaney, 2011).

3.1.4. Strong Th2 response in HD vaccine recipients in virus-challenged cells

To examine the effect of vaccine dose, on ex vivo cytokine responses, we measured cytokine levels in supernatants from ex vivo influenza-challenged PBMCs (Fig. 1f–i). While SD vaccination did not impact the TNF-α response post-vaccination (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, p = 0.63), HD vaccination did result in a significantly higher mean TNF-α response measured at week 4 (Fig. 1f), but this was not maintained at week 10 (Table S3a). Although the mean IFN-γ response at week 4 was not significantly different between vaccine groups, the same trend seen with TNF-α responses was observed with IFN-γ (Fig. 1f). Specifically, SD vaccination did not significantly impact post-vaccination IFN-γ responses (p = 0.97), and the fold increase in IFN-γ response in the HD recipients was similar to that of SD recipients at week 10 (Table S3a). While SD vaccination in older adults did not impact TNF-α or IFN-γ responses, IL-10 responses were significantly increased (p ≤ 0.0001), with a response that was almost 3-fold higher in the HD compare to the SD group (Fig. 1h, Table S3a). This dramatic increase in the IL-10 response to virus-challenge post-vaccination resulted in a significant lowering of the IFN-γ:IL-10 ratio in the HD group (Fig. 1i). IL-1β and IL-6 levels were not significantly different between vaccine groups (Fig. S2). IL-15 and IL-22 responses were measured, but not analyzed as the majority of measurements fell below the lower limit of detection (2.5 pg/ml and 0.021 ng/ml respectively).

The analysis of the cytokine response in recipients of HD vaccine suggests that this vaccine stimulates a strong and sustained Th2 but not a Th1 memory response. As we have previously reported for SD vaccine (McElhaney et al., 2006; Shahid et al., 2010), the IFN-γ:IL-10 ratio variably declines at 4-weeks post-vaccination due to a peak in the IL-10 response at 4-weeks post-vaccination, whereas any IFN-γ response is delayed to 10-weeks post-vaccination. This variability in the pattern of result may reflect the different methodologies used for cytokine quantification (single cytokine ELISA-based assays in our earlier studies vs. multiplex Luminex bead based assay in this study). Various studies have reported on the correlation between ELISA and Luminex assays, finding a correlation between the two methods, but Luminex assays generally have a greater dynamic range and may differ in the absolute cytokine concentrations depending on the cytokine and kit used (Elshal and McCoy, 2006). For example, it was reported that a multiplex-based IFN-γ quantification was 2–4 fold lower and IL-10 levels were 2-fold higher than that quantified by ELISA (duPont et al., 2005). As such, the trends observed between assays are comparable when analyzing absolute concentrations, but may be obscured when ratios are used.

3.2. Influenza infection in older adults results in a strong Th1 and Th2 response to influenza virus-challenge

A small number of subjects became infected with influenza, allowing for the comparison of antibody and cytokine responses to determine if pre-vaccination responses were correlated with influenza infection susceptibility.

Seven older adult subjects became infected with influenza A/H3N2 at some point around the week 10 post-vaccination time point, all of whom seroconverted post-infection. Of those developing infection, 3 subjects received HD vaccine and 4 subjects received SD vaccine. Of the 7 subjects with influenza infection, 3 did not meet the criteria for ILI.

In this cohort, iGrB, TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-10 responses at week 0 or week 4 were not predictive of influenza infection (based on logistic regression analysis), after adjustment for age, CMV status, vaccine dose and sex (Table S4). However, the analysis was underpowered with only 7 subjects, 2 of whom were asymptomatic seroconverters, and may represent a Type 2 error.

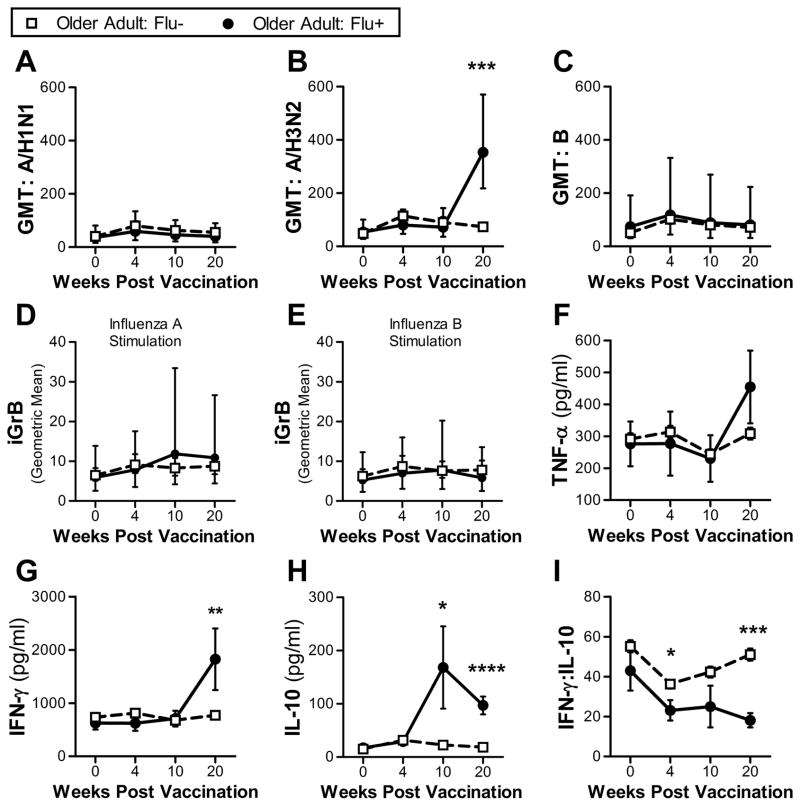

As previously discussed, vaccination of older adults, regardless of dose resulted in a post-vaccination (week 4) increase in GMT, IL-10 and iGrB responses to live influenza virus-challenge. However, while the Flu+ subjects demonstrated no increase in these T-cell responses following vaccination (Fig. 2), a significant change was demonstrated following influenza infection. Seroconversion and an increase in influenza A/H3N2 GMT following infection is delayed for a 2–4 week period after which peak antibody titers are observed (Richman et al., 1976), thus explaining why the antibody response to infection at 10-weeks post-vaccination, was not detected until the 20-week post-vaccination time point.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of antibody and cellular responses between Flu− older adults (n = 99) and Flu+ older adults (n = 7) at 4 time points: pre-vaccination (week 0) and 4, 10 and 20 weeks post-vaccination. (a–c) Serum GMT for 3 influenza strains (A/H1N1, A/H3N2 and B). Error bars denote 95% CI. Significant differences between groups at a single time point determined using 2-sided Mann-Whitney test. Geometric mean iGrB response in PBMCs challenged with influenza A/H3N2 (d) and B (e). Error bars denote 95% CI. (f–h) Mean cytokine levels (TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-10) in supernatants of ex vivo live influenza virus-challenged PBMCs (A/H3N2). Error bars denote SEM. Significant differences between groups at a single time point determined using 2-sided Mann-Whitney test. (i) Mean IFN-γ:IL-10 ratio in supernatants of ex vivo live influenza virus-challenged PBMCs (A/H3N2). Error bars denote SEM. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01, ***, p ≤ 0.001, ****, p ≤ 0.0001.

When compared to pre-infection responses to the A/H3N2 virus-challenge (week 4), the 7 Flu+ subjects showed a significant increase in iGrB and IL-10 responses at week 10 and 20; and TNF-α, IFN-γ and IFN-γ:IL-10 at week 20 (Fig. 2). Furthermore, TNF-α, IFN-γ and IFN-γ:IL-10, but not iGrB responses at week 20 were able to differentiate Flu+ from Flu− subjects (based on logistic regression analysis) (Table S4). Influenza A/H3N2 infection has no effect on the iGrb responses measured in PBMCs challenged ex vivo with influenza B (Fig. 2d, e). These results suggest that the weak iGrB response to vaccination in influenza-susceptible older adults is a reversible defect of T-cell memory that can be restored by natural influenza infection, and re-stimulated with a subsequent influenza vaccination (McElhaney et al., 2009).

Although the analysis of T-cell responses in Flu+ older subjects was not statistically powered to establish correlates protection following influenza vaccination, we were able to demonstrate a strong Th1 and Th2 memory response following natural infection with influenza A/H3N2.

3.3. CMV seropositivity does not impact response to influenza vaccination, but impairs response to influenza virus-challenge

When the study cohort of older adults was characterized based on CMV status (CMV−, n = 46 and CMV+, n = 60), age, vaccine dose, medical conditions and medications were similar between groups, although sex (p = 0.06) approached significance (Table S1). A higher level of frailty has been reported in CMV+ subjects (Schmaltz et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2010), but was not significant in this study (Fried Frailty, p = 0.09; Frailty Index, p = 0.42).

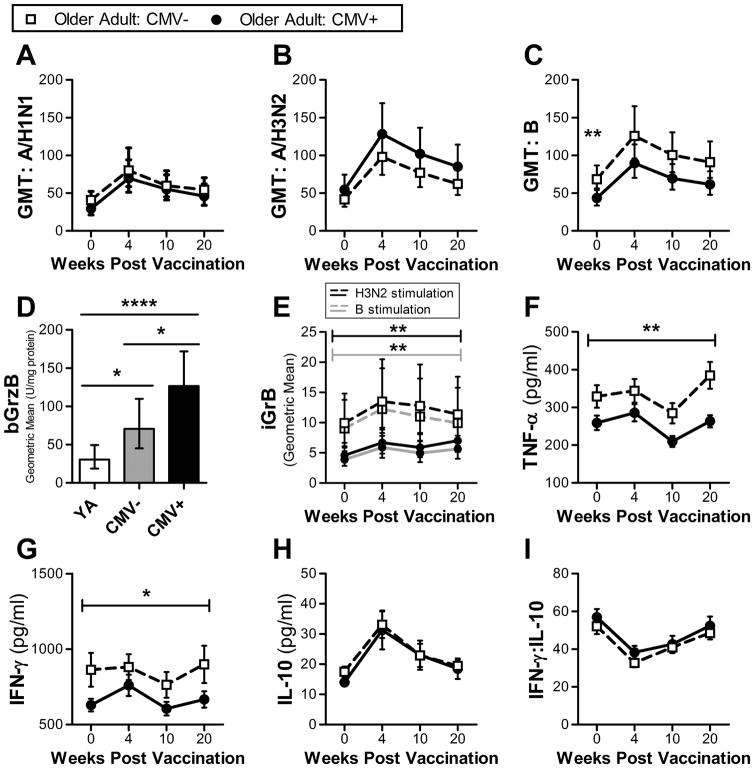

Inconsistent findings of the impact of CMV on antibody responses to vaccination have been reported (Wald et al., 2013; Frasca et al., 2015; Furman et al., 2015; McElhaney et al., 2015; Haq et al., 2016). While the influenza B GMT was higher pre-vaccination in CMV− subjects, there was no difference in GMT fold increase (Fig. 3c, Table S2c) or seroprotection rates between CMV+ and CMV− older adults post-vaccination. Instead, we observed a trend over the course of 20 weeks of higher A/H3N2 GMT in CMV+ subjects and higher influenza B GMT in CMV− subjects (although not statistically significant (Fig. 3b, c)). A correlation in CMV+ subjects between CMV titer and cytokine or GrB levels was not observed, although there was a weak positive correlation between CMV titer and influenza antibody titer at week 4 for the A/H1N1 (r = 0.27, p = 0.05) and B (r = 0.37, p = 0.01) strains that was not significant for A/H3N2 strain (r = 0.25, p = 0.08).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of antibody and cellular responses between CMV seronegative older adults (CMV−, n = 43) and CMV seropositive older adults (CMV+, n = 56); at 4 time points: pre-vaccination (week 0) and 4, 10 and 20 weeks post-vaccination. (a–c) Serum GMT for 3 influenza strains (A/H1N1, A/H3N2 and B). Significance between groups at a single time pointed determined using 2-sided Mann-Whitney test. Error bars denote 95% CI. (d) Geometric mean bGrB in non-stimulated T-cells in young adults (n = 19) and CMV− and CMV+ older adults. Error bars denote 95% CI. Significant differences were determined using t-test. (e) Geometric mean iGrB response in PBMCs challenged with either influenza A/H3N2 (black line) or B (grey line). Significance between groups across the 4 time points was determined by ANOVA. Error bars denote 95% CI. (f–h) Mean cytokine levels (TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-10) in supernatants of ex vivo live influenza virus-challenged PBMCs (A/H3N2). Error bars denote SEM. Significance between groups across the 4 time points was determined by ANOVA. (i) Mean IFN-γ:IL-10 ratio in supernatants of ex vivo live influenza virus-challenged PBMCs (A/H3N2). Error bars denote SEM. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p = 0.01; ****, p ≤ 0.001.

We have previosuly shown that GrB levels in unstimulated T-cells (bGrB) are higher is CMV+ compared to CMV− older adults (McElhaney et al., 2012; Haq et al., 2016) possibly due to continued activation of CMV-specific T-cells to maintain CMV latency. This study mirrors the previous studies (Fig. 3d). Our previously unpublished data were supported in this study showing the significant difference in bGrB levels between age groups, with older adults having several fold higher levels of bGrB activity compared to young adults. A significantly greater iGrB response was observed in CMV− compared to CMV+ older adults, regardless of vaccine dose (Fig. 3e), as has been reported previously (Haq et al., 2016). Additionally, bGrB levels were found to be strongly correlated with the iGrB response pre-vaccination in both young (r = −0.7, p = 0.005) and older adults (r = −0.9, p ≤ 0.0001), regardless of CMV status (Fig. S3).

While there was no difference in the cytokine response (fold increase) to vaccination based on CMV status (Table S3c), TNF-α and IFN-γ levels were significantly increased in CMV− compared to CMV+ older adults over the course of the 20 weeks (Fig. 3f,g). Taken together, these data suggest that CMV status does not impact the response to vaccination, but rather impairs the cellular responses to influenza virus challenge.

4. Discussion

The study presented here investigates the impact of influenza vaccine dose, influenza infection and CMV serostatus on the antibody and cellular immune response in older adults using an ex vivo live influenza virus-challenge model.

The decline with aging, in the antibody response to influenza vaccination and the associated loss of vaccine efficacy has been attributed to age-related changes in the T-cells (Goronzy et al., 2001; Saurwein-Teissl et al., 2002). The HD vaccine was designed to overcome these changes and has been shown to significantly increase antibody responses in older adults when compared to SD vaccines (Couch et al., 2007; Falsey et al., 2009; DiazGranados et al., 2013; DiazGranados et al., 2014). Using longitudinal sampling, we found that HD compared to SD vaccination significantly improved both the magnitude and duration of the antibody response to the A/H1N1 and B strains out to 20-weeks post-vaccination, but the same did not hold true for the A/H3N2 strain. This may be explained by the higher pre-vaccination A/H3N2 titers (relative to other strains), resulting in a ceiling effect wherein the GMT increase may be limited by high pre-vaccination titers in both young and older adults (Van Epps et al., 2017).

Influenza antibody titers have been shown to be a poor predictor of vaccine failure in older adults (McElhaney et al., 2006; McElhaney et al., 2009), and is particularly important in years where the vaccine strains do not match the circulating strains, thus resulting in poor antibody-mediated protection (Dunning et al., 2016). This may have been the case in this study as the vaccine and circulating A/H3N2 strains were reported to be a poor match (Flannery et al., 2015) with little cross-reactivity with other A/H3N2 strains (Xie et al., 2015). It also highlights the need for vaccines to induce T-cell memory, and provide cross protection between strains. Thus, measures of cellular immune responses may complement antibody responses to predict vaccine effectiveness.

CTL responses are protective against influenza infection (La Gruta and Turner, 2014). Specifically, iGrB responses and IFN-γ:IL-10 ratios have been found to be reliable correlates of protection against influenza in older adults (McElhaney et al., 2006; McElhaney et al., 2009; Shahid et al., 2010). Previous studies reporting that the HD influenza vaccination does not improve the IFN-γ response (Chen et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2016) (using ELISpot and flow cytometry respectively) are not supported by our findings. This may be related to differences in measures of cell frequencies compared to cytokine levels, and changes that may be due to an increase in the amount of cytokine produced on a per cell basis in response to ex vivo virus-challenge. In our study, HD but not SD vaccination in older adults increased IFN-γ, TNF-α, and iGrB responses to live virus-challenge at 4-weeks post-vaccination, but not at week 10. In contrast, IL-10 (which has been correlated with antibody response to influenza vaccination (Wang et al., 2012)) was elevated in HD compared to SD recipients up to 20-weeks post-vaccination resulting in a lower IFN-γ:IL-10 ratio in the HD compared to the SD group. A high IFN-γ:IL-10 ratio has been identified as a correlate of protection against influenza in older adults (McElhaney et al., 2006; McElhaney et al., 2009; Shahid et al., 2010) suggesting that the cellular immune response induced by HD vaccination may not be optimal.

The skewing of the T-cell response toward a Th2 (IL-10) response in recipients of the HD influenza vaccine may be explained by studies of antigen dosage. Low dose influenza peptides favour a Th1 response, and at very high concentrations favour Th2/T follicular helper (TFH) cell response (Brown et al., 2009; Pompano et al., 2014). The relationship between TFH and antigen dose corresponds to a recent study founding a greater frequency of (peripheral) pTFH post-vaccination in those receiving HD compared to SD vaccine (Pilkinton et al., 2017). It has also been shown that the frequency of activated pTFH cells following vaccination is correlated with antibody responses to vaccination (Bentebibel et al., 2013; Spensieri et al., 2013; Herati et al., 2014), consistent with that observed with HD vaccination.

As mentioned previously, CTL responses to ex vivo influenza challenge are a correlate of protection, and although our study was underpowered for this same type of analysis with only seven Flu+ subjects, we were able to differentiate Flu+ from Flu− subjects based on IL-10, IFN-γ and TNF-α responses, and a significant increase in iGrB levels following infection. Importantly, we were also able to demonstrate that a poor iGrB response to influenza vaccination is a reversible defect in light of the response to natural influenza infection. We have also previously shown that this same improved GrB response can be re-stimulated by a subsequent influenza vaccination (McElhaney et al., 2009). In addition, we have shown that these age-related changes in the CD8+ CTL response can be restored with the addition of IL-2 and IL-6 to PBMCs challenged ex vivo with influenza A/H3N2 (Zhou et al., 2016) or the addition of a TLR4 agonist to influenza vaccine, in in vitro studies of their subsequent response to live virus-challenge in older adult PBMC cultures (Behzad et al., 2011). Of the cytokine responses observed, influenza infection appeared to have the greatest impact on IL-10 responses. IL-10 may be produced by Th2 or regulatory T-cells (Tregs), in the latter case, in an attempt to mitigate immunopathology (Sanchez et al., 2012) but in the case of dysregulated cytokine production could be a contributing factor to the poor outcomes of influenza observed in older adults.

Our results contribute to the discordant observations of the effect of CMV status and interaction with age, on the antibody response to the different influenza vaccine strains (Wald et al., 2013; Frasca et al., 2015; Furman et al., 2015; McElhaney et al., 2015; Haq et al., 2016). One possible explanation is that vaccination may restimulate the B-cells and thus, antibody responses to the H1N1 strains circulating during the childhood of the older adult cohort, due to their similarity to currently circulating H1N1 strains (Jacobs et al., 2012). In addition, serological studies require much larger sample sizes to detect differences between groups and avoid Type 2 errors in the analysis.

Recent studies have shown that the use of CMV DNA (latent viral load) detected in monocytes is a better measure of current CMV status and burden compared to serum IgG titers (a marker of CMV exposure, and not necessarily current infection). As such, it has been suggested that latent CMV viral load may be a stronger correlate of immunological burden and hence could be the reason behind discrepant findings in this and other studies of the impact of CMV on immunological responses to infection and vaccination. This is supported by high latent viral load being correlated with an increased breadth and magnitude of the CMV-specific CD8+ T-cell IFN-γ responses (Jackson et al., 2017) as well as serum IL-6 levels (Li et al., 2014). Although, it should be noted that there are conflicting reports on the correlation of age, CMV IgG titer and CMV DNA (Parry et al., 2016; Jackson et al., 2017), suggesting that further investigation of the role of CMV DNA and the immune response to influenza.

GrB and perforin have a key cytolytic function in the killing of virus infected cells in a directed manner. In the absence of perforin, GrB accumulates and has been shown to cause degradation of the extracellular matrix and stimulate an inflammatory response (Hiebert et al., 2011; Parkinson et al., 2015). CMV in older adults has been linked to increased levels of late differentiated T-cells (CD8+CD28−) (Di Benedetto et al., 2015; van der Heiden et al., 2016) and a decline in the effector memory CD8+ T-cell response to influenza (Xie and McElhaney, 2007). Furthermore, the frequency of late differentiated effector T-cells correlates with bGrB activity (McElhaney et al., 2012; Haq et al., 2016). The associated pro-inflammatory state in these individuals may be potentiated by the release of GrB in the absence of perforin creating a toxic environment leading to tissue injury (Granville, 2010; Afonina et al., 2011; Hiebert et al., 2011). We found that an increase in bGrB levels in T-cells from CMV+ older adults was accompanied by lower iGrB responses to ex vivo live virus-challenge, as we have shown previously (Haq et al., 2016). Interestingly, the inverse correlation between bGrB and iGrB responses to influenza challenge extended to young adults, although without any impact iGrB responses to vaccination. The lower iGrB response in CMV+ older adults corresponded to the same trend in TNF-α and IFN-γ as further evidence of the immunological burden of CMV in older adults. These results suggest that CMV seropositivity is an important determinant of the CTL response to influenza. Further studies are needed to elucidate the impact of CMV on the response to and outcomes of influenza infection.

5. Conclusion

This study provides new insights into the role of vaccine dose, CMV status and influenza on antibody and cellular immune responses to influenza in older adults. Here we demonstrated that HD influenza vaccines induce strong and long lived Th2 responses (antibody and IL-10), but have a limited impact on Th1 responses (iGrB, IFN-γ). In contrast, recent influenza infection is associated with the development of strong Th1 and Th2 memory responses and restores the iGrB response to ex vivo influenza challenge. Furthermore, CMV seropositivity appears to impair the Th1 response to influenza (iGrB and IFN-γ) but does not alter the magnitude of the response to vaccination. In summary, influenza vaccination stimulates a Th2 response to influenza challenge in older adult PBMCs, while CMV seropositivity further impairs the Th1 response. Together, these observations suggest a degree of resiliency in the aged T-cells that could be targeted in the design of new influenza vaccines to stimulate a Th1 memory response and restore the iGrB response to influenza challenge in older adults. Given the broad protection offered by the cell-mediated immune response to different influenza strains, this would be particularly significant in years when the vaccine and circulating influenza strains are poorly matched.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by: the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging (R01 AG048023) and the Northern Ontario Heritage Fund Corporation (A-17-07).

Abbreviations

- bGrB

baseline granzyme B

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- CTL

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte

- GMT

geometric mean titer

- HA

hemagglutinin

- HAI

hemagglutination inhibition assay

- HD

high dose

- iGrB

inducible granzyme B

- ILI

influenza like illness

- MLD

minimum level of detection

- SD

standard dose

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2017.09.015.

Author contributions

Study design by JEM and GAK. Data analysis was performed by SM and AK. The manuscript was written by SM. Final review and editing of manuscript by SM, AK, GAK and JEM.

Conflict of interest

JEM has participated on advisory boards for GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, and Pfizer and on data monitoring boards for Sanofi Pasteur; she has participated in clinical trials sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline and has received honoraria and travel and accommodation reimbursements for presentations sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur and Pfizer.

SM, AK and GAK have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Afonina IS, Tynan GA, Logue SE, Cullen SP, Bots M, Lüthi AU, Reeves EP, McElvaney NG, Medema JP, Lavelle EC, Martin SJ. Granzyme B-dependent proteolysis acts as a switch to enhance the pro-inflammatory activity of IL-1α. Mol Cell. 2011;44(2) doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.037. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behzad H, Huckriede ALW, Haynes L, Gentleman B, Coyle K, Wilschut JC, Kollmann TR, Reed SG, McElhaney JE. GLA-SE, a synthetic toll-like receptor 4 agonist, enhances T-cell responses to influenza vaccine in older adults. J Infect Dis. 2011;205(3) doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir769. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jir769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentebibel S-E, Lopez S, Obermoser G, Schmitt N, Mueller C, Harrod C, Flano E, Mejias A, Albrecht RA, Blankenship D, Xu H, Pascual V, Banchereau J, Garcia-Sastre A, Palucka AK, Ramilo O, Ueno H. Induction of ICOS +CXCR3+CXCR5+ TH cells correlates with antibody responses to influenza vaccination. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(176) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3005191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DM, Kamperschroer C, Dilzer AM, Roberts DM, Swain SL. IL-2 and antigen dose differentially regulate perforin- and FasL-mediated cytolytic activity in antigen specific CD4(+) T cells. Cell Immunol. 2009;257(1–2) doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.03.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WH, Cross AS, Edelman R, Sztein MB, Blackwelder WC, Pasetti MF. Antibody and Th1-type cell-mediated immune responses in elderly and young adults immunized with the standard or a high dose influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2011;29(16) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch RB, Winokur P, Brady R, Belshe R, Chen WH, Cate TR, Sigurdardottir B, Hoeper A, Graham IL, Edelman R, He F, Nino D, Capellan J, Ruben FL. Safety and immunogenicity of a high dosage trivalent influenza vaccine among elderly subjects. Vaccine. 2007;25(44) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.08.042. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derhovanessian E, Larbi A, Pawelec G. Biomarkers of human immunosenescence: impact of cytomegalovirus infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21(4) doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Benedetto SED, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, Goldeck D, Muller L, Pawelec G. Impact of age, sex and CMV-infection on peripheral T cell phenotypes: results from the Berlin BASE-II Study. Biogerontology. 2015;16(5) doi: 10.1007/s10522-015-9563-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10522-015-9563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiazGranados C, Dunning A, Jordanov E, Landolfi V, Denis M, Talbot H. High-dose trivalent influenza vaccine compared to standard dose vaccine in elderly adults: safety, immunogenicity and relative efficacy during the 2009–2010 season. Vaccine. 2013;31(6) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.12.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiazGranados CA, Dunning AJ, Kimmel M, Kirby D, Treanor J, Collins A, Pollak R, Christoff J, Earl J, Landolfi V, Martin E, Gurunathan S, Nathan R, Greenberg DP, Tornieporth NG, Decker MD, Talbot HK. Efficacy of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccine in older adults. NEJM. 2014;371(7) doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315727. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1315727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning AJ, DiazGranados CA, Voloshen T, Hu B, Landolfi VA, Talbot HK. Correlates of protection against influenza in the elderly: results from an influenza vaccine efficacy trial. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2016;23(3) doi: 10.1128/CVI.00604-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.00604-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Pont NC, Wang K, Wadhwa PD, Culhane JF, Nelson EL. Validation and comparison of luminex multiplex cytokine analysis kits with ELISA: Determinations of a panel of nine cytokines in clinical sample culture supernatants. J Reprod Immunol. 2005;66(2) doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2005.03.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jri.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effros RB. Role of T lymphocyte replicative senescence in vaccine efficacy. Vaccine. 2007;25(4):599–604. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elshal MF, McCoy JP. Multiplex Bead Array Assays: Performance Evaluation and Comparison of Sensitivity to ELISA. Methods. 2006;38(4) doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.11.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsey A, Treanor J, Tornieporth N, Capellan J, Gorse G. Randomized, double-blind controlled phase 3 trial comparing the immunogenicity of high-dose and standard-dose influenza vaccine in adults 65 years of age and older. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(2) doi: 10.1086/599790. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/599790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery B, Clippard J, Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Jackson ML, Jackson LA, Monto AS, Petrie JG, McLean HQ, Belongia EA, Gaglani M, Berman L, Foust A, Sessions W, Thaker SN, Spencer S, Fry AM, Fry AM. Early estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness - United States, January 2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep MMWR. 2015;64(1):10–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Landin AM, Phillips M, Lechner SC, Ryan JG, Blomberg BB. Intrinsic defects in B cell response to seasonal influenza vaccination in elderly humans. Vaccine. 2010;28(51) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Landin AM, Blomberg BB. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) seropositivity decreases B cell responses to the influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2015;33(12) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.071. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Blomberg BB. The generation of memory B cells is maintained, but the antibody response is not, in the elderly after repeated influenza immunizations. Vaccine. 2016;34(25) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):146–156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman D, Jojic V, Sharma S, Shen-Orr S, Angel CJL, Onengut-Gumuscu S, Kidd B, Maecker HT, Concannon P, Dekker CL, Thomas PG, Davis MM. Cytomegalovirus infection improves immune responses to influenza. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(281) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa2293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijzen K, Liu WM, Visontai I, Oftung F, van der Werf S, Korsvold GE, Pronk I, Aaberge IS, Tüttő A, Jankovics I, Jankovics M, Gentleman B, McElhaney JE, Soethout EC. Standardization and validation of assays determining cellular immune responses against influenza. Vaccine. 2010;28(19) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.076. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gionet L. Health at a Glance - flu vaccination rates in Canada. Statistics Canada Cat no 82-624-X 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin K, Viboud C, Simonsen L. Antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly: a quantitative review. Vaccine. 2006;24(8) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goronzy JJ, Fulbright JW, Crowson CS, Poland GA, O’Fallon WM, Weyand CM. Value of immunological markers in predicting responsiveness to influenza vaccination in elderly individuals. J Virol. 2001;75(24) doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12182-12187.2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.75.24.12182-12187.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granville DJ. Granzymes in disease: bench to bedside. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17(4) doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2009.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haq K, Fulop T, Tedder G, Gentleman B, Garneau H, Meneilly GS, Kleppinger A, Pawelec G, McElhaney JE. Cytomegalovirus seropositivity predicts a decline in the T cell but not the antibody response to influenza in vaccinated older adults independent of type 2 diabetes status. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (glw216) 2016 doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw216. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glw216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Herati RS, Reuter MA, Dolfi DV, Mansfield KD, Aung H, Badwan OZ, Kurupati RK, Kannan S, Ertl H, Schmader KE, Betts MR, Canaday DH, Wherry EJ. Circulating CXCR5+PD-1+ response predicts influenza vaccine antibody responses in young adults but not elderly adults. J Immunol. 2014;193(7) doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302503. http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1302503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert PR, Boivin WA, Abraham T, Pazooki S, Zhao H, Granville DJ. Granzyme B contributes to extracellular matrix remodeling and skin aging in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46(6) doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.02.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höpping AM, McElhaney J, Fonville JM, Powers DC, Beyer WEP, Smith DJ. The confounded effects of age and exposure history in response to influenza vaccination. Vaccine. 2016;34(4) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.058. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SE, Sedikides GX, Okecha G, Poole EL, Sinclair JH, Wills MR. Latent Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Infection Does Not Detrimentally Alter T Cell Responses in the Healthy Old, But Increased Latent CMV Carriage Is Related to Expanded CMV-Specific T Cells. Front Immunol. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00733. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JH, Archer BN, Baker MG, Cowling BJ, Heffernan RT, Mercer G, Uez O, Hanshaoworakul W, Viboud C, Schwartz J, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, Lipsitch M. Searching for sharp drops in the incidence of pandemic A/H1N1 influenza by single year of age. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042328. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BJ, Costelloe EO, Fitzpatrick DR, Haanen JBAG, Schumacher TNM, Brown LE, Kelso A. Single-cell perforin and granzyme expression reveals the anatomical localization of effector CD8(+) T cells in influenza virus-infected mice. PNAS. 2003;100(5) doi: 10.1073/pnas.0538056100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0538056100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Talbot HK, Mishina M, Zhu Y, Chen J, Cao W, Reber AJ, Griffin MR, Shay DK, Spencer SM, Sambhara S. High-dose influenza vaccine favors acute plasmablast responses rather than long-term cellular responses. Vaccine. 2016;34(38) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.07.018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Gruta NL, Turner SJ. T cell mediated immunity to influenza: mechanisms of viral control. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(8) doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.06.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster GI, Febbraio MA. The immunomodulating role of exercise in metabolic disease. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(6) doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.02.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Weng P, Najarro K, Xue Q-L, Semba RD, Margolick JB, Leng SX. Chronic CMV infection in older women: Longitudinal comparisons of CMV DNA in peripheral monocytes, anti-CMV IgG titers, serum IL-6 levels, and CMV pp65 (NLV)-specific CD8(+) T-cell frequencies with twelve year follow-up. Exp Gerentol. 2014;0 doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.01.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney JE, Gentleman B. Cell-mediated immune response to influenza using ex vivo stimulation and assays of cytokine and granzyme B responses. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;2015:1940–6029. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2963-4_11. Electronic. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2963-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney JE, Xie D, Hager WD, Barry MB, Wang Y, Kleppinger A, Ewen C, Kane KP, Bleackley RC. T cell responses are better correlates of vaccine protection in the elderly. J Immunol. 2006;176(10) doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6333. http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney JE, Ewen C, Zhou X, Kane KP, Xie D, Hager WD, Barry MB, Kleppinger A, Wang Y, Bleackley RC. Granzyme B: correlates with protection and enhanced CTL response to influenza vaccination in older adults. Vaccine. 2009;27(18) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.136. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney JE, Zhou X, Talbot HK, Soethout E, Bleackley RC, Granville DJ, Pawelec G. The unmet need in the elderly: how immunosenescence, CMV infection, co-morbidities and frailty are a challenge for the development of more effective influenza vaccines. Vaccine. 2012;30(12) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney JE, Garneau H, Camous X, Dupuis G, Pawelec G, Baehl S, Tessier D, Frost EH, Frasca D, Larbi A, Fulop T. Predictors of the antibody response to influenza vaccination in older adults with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2015;3(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2015-000140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2015-000140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil S, Johnstone J, Rockwood M, MacKinnon-Cameron D, Wang H, Ye L, Andrew M. Impact of hospitalizaiton due to influenza on frailty in older adults: toward a better understanding of burden of disease. Infectious Diseases Society of America; San Diego, CA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson LG, Toro A, Zhao H, Brown K, Tebbutt SJ, Granville DJ. Granzyme B mediates both direct and indirect cleavage of extracellular matrix in skin after chronic low-dose ultraviolet light irradiation. Aging Cell. 2015;14(1) doi: 10.1111/acel.12298. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/acel.12298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry HM, Zuo J, Frumento G, Mirajkar N, Inman C, Edwards E, Griffiths M, Pratt G, Moss P. Cytomegalovirus viral load within blood increases markedly in healthy people over the age of 70 years. Immun Ageing. 2016;13 doi: 10.1186/s12979-015-0056-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12979-015-0056-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkinton MA, Nicholas KJ, Warren CM, Smith RM, Yoder SM, Talbot HK, Kalams SA. Greater activation of peripheral T follicular helper cells following high dose influenza vaccine in older adults forecasts seroconversion. Vaccine. 2017;35(2) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.059. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompano RR, Chen J, Verbus EA, Han H, Fridman A, McNeely T, Collier JH, Chong AS. Titrating T-cell epitopes within self-assembled vaccines optimizes CD4+ helper T cell and antibody outputs. Adv Healthc Mater. 2014;3(11) doi: 10.1002/adhm.201400137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201400137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman DD, Murphy BR, Baron S, Uhlendorf C. Three strains of influenza A virus (H3N2): interferon sensitivity in vitro and interferon production in volunteers. J Clin Microbiol. 1976;3(3):223–226. doi: 10.1128/jcm.3.3.223-226.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty defined by deficit accumulation and geriatric medicine defined by frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez AM, Zhu J, Huang X, Yang Y. The development and function of memory regulatory T cells after acute viral infections. J Immunol. 2012;189(6) doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200645. http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1200645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurwein-Teissl M, Lung TL, Marx F, Gschösser C, Asch E, Blasko I, Parson W, Böck G, Schönitzer D, Trannoy E, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Lack of antibody production following immunization in old age: association with CD8+CD28−T cell clonal expansions and an imbalance in the production of Th1 and Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 2002;168(11) doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5893. http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schanzer DL, Fau Tam Tw, Langley JM, Fau Langley Jm, Winchester BT. Influenza-attributable deaths, Canada 1990–1999. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135(7):1109–1116. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807007923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaltz HN, Fried LP, Xue Q-L, Walston J, Leng SX, Semba RD. Chronic cytomegalovirus infection and inflammation are associated with prevalent frailty in community-dwelling older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(5) doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53250.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahid Z, Kleppinger A, Gentleman B, Falsey AR, McElhaney JE. Clinical and immunologic predictors of influenza illness among vaccinated older adults. Vaccine. 2010;28(38) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.036. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen L, Fukuda K, Schonberger LB, Cox N. The impact of influenza epidemics on hospitalizations. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(3):831–837. doi: 10.1086/315320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen L, Taylor RJ, Viboud C, Miller MA, Jackson LA. Mortality benefits of influenza vaccination in elderly people: an ongoing controversy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(10) doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70236-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70236-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spensieri F, Borgogni E, Zedda L, Bardelli M, Buricchi F, Volpini G, Fragapane E, Tavarini S, Finco O, Rappuoli R, Del Giudice G, Galli G, Castellino F. Human circulating influenza-CD4+ ICOS1+IL-21+ T cells expand after vaccination, exert helper function, and predict antibody responses. PNAS. 2013;110(35) doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311998110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1311998110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staras SA, Dollard SC, Radford KW, Flanders WD, Pass RF, Cannon MJ. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the United States, 1988–1994. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(9) doi: 10.1086/508173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/508173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson I, Das RG, Wood JM, Katz JM. Comparison of neutralising antibody assays for detection of antibody to influenza A/H3N2 viruses: An international collaborative study. Vaccine. 2007;25(20) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.039. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PG, Keating R, Hulse-Post DJ, Doherty PC. Cell-mediated Protection in Influenza Infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(1) doi: 10.3201/eid1201.051237. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1201.051237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the united states. JAMA. 2004;292(11) doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1333. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.11.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M, Shay D, Zhou H, Bridges C, Cheng P, Burns E, Bresee J, Cox N. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza - United States, 1976–2007. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep MMWR. 2010;59(33):1057–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heiden M, van Zelm MC, Bartol SJW, de Rond LGH, Berbers GAM, Boots AMH, Buisman A-M. Differential effects of Cytomegalovirus carriage on the immune phenotype of middle-aged males and females. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep26892. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep26892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Epps P, Tumpey T, Pearce MB, Golding H, Higgins P, Hornick T, Burant C, Wilson BM, Banks R, Gravenstein S, Canaday DH. Preexisting immunity, not frailty phenotype, predicts influenza postvaccination titers among older veterans. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2017;24(3) doi: 10.1128/CVI.00498-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/cvi.00498-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald A, Selke S, Magaret A, Boeckh M. Impact of human cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection on immune response to pandemic 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine in healthy adults. J Med Virol. 2013;85(9) doi: 10.1002/jmv.23642. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.23642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GC, Kao WHL, Murakami P, Xue Q-L, Chiou RB, Detrick B, McDyer JF, Semba RD, Casolaro V, Walston JD, Fried LP. Cytomegalovirus infection and the risk of mortality and frailty in older women: A prospective observational cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(10) doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq062. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S-M, Tsai M-H, Lei H-Y, Wang J-R, Liu C-C. The regulatory T cells in anti-influenza antibody response post influenza vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8(9) doi: 10.4161/hv.21117. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/hv.21117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster R, Cox N, Stöhr K. WHO Manual on Animal Influenza Diagnosis and Surveillance. World Health Organization, Department of Communicable Disease Surveillance and Response; 2002. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/influenza/en/whocdscsrncs20025rev.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wood JM, Gaines-Das RE, Taylor J, Chakraverty P. Comparison of influenza serological techniques by international collaborative study. Vaccine. 1994;12(2):167–174. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie D, McElhaney JE. Lower GrB+CD62L(high) CD8 T(CM) effector lymphocyte response to influenza virus in older adults is associated with increased CD28(null) CD8 T lymphocytes. Mech Aging Dev. 2007;128(5–6) doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.05.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Wan X-F, Ye Z, Plant EP, Zhao Y, Xu Y, Li X, Finch C, Zhao N, Kawano T, Zoueva O, Chiang M-J, Jing X, Lin Z, Zhang A, Zhu Y. H3N2 Mismatch of 2014–15 northern hemisphere influenza vaccines and head-to-head comparison between human and ferret antisera derived antigenic maps. Sci Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep15279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep15279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, McElhaney JE. Age-related changes in memory and effector T cells responding to influenza A/H3N2 and pandemic A/H1N1 strains in humans. Vaccine. 2011;29(11) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Hopkins JW, Wang C, Brahmakshatriya V, Swain SL, Kuchel GA, Haynes L, McElhaney JE. IL-2 and IL-6 cooperate to enhance the generation of influenza-specific CD8 T cells responding to live influenza virus in aged mice and humans. Oncotarget. 2016;7(26) doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10047. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.10047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.