Abstract

Background

Hispanic children are disproportionally overweight and obese compared to their non-Hispanic white counterparts in the US. Community-wide, multi-level interventions have been successful to promote healthier nutrition, increased physical activity (PA), and weight loss. Using community-based participatory approach (CBPR) that engages community members in rural Hispanic communities is a promising way to promote behavior change, and ultimately weight loss among Hispanic children.

Objectives

Led by a community-academic partnership, the Together We STRIDE (Strategizing Together Relevant Interventions for Diet and Exercise) aims to test the effectiveness of a community-wide, multi-level intervention to promote healthier diets, increased PA, and weight loss among Hispanic children.

Methods

The Together We STRIDE is a parallel quasi-experimental trial with a goal of recruiting 900 children aged 8-12 years nested within two communities (one intervention and one comparison). Children will be recruited from their respective elementary schools. Components of the 2-year multi-level intervention include comic books (individual-level), multi-generational nutrition and PA classes (family-level), teacher-led PA breaks and media literacy education (school-level), family nights, a farmer's market and a community PA event (known as ciclovia) at the community-level. Children from the comparison community will receive two newsletters. Height and weight measures will be collected from children in both communities at three time points (baseline, 6-months, and 18-months).

Summary

The Together We STRIDE study aims to promote healthier diet and increased PA to produce healthy weight among Hispanic children. The use of CBPR approach and the engagement of the community will springboard strategies for intervention' sustainability.

Clinical Trials Registration Number

NCT02982759 Retrospectively registered.

Keywords: Childhood Obesity, Hispanic Children, Multi-level Interventions, Community-based Participatory Research

Introduction

Overweight and obesity among children are associated with an increased risk of childhood morbidity, such as type 2 diabetes [1, 2] and cardiovascular disease [3], and has been shown to affect long-term health, including future adult obesity and morbidity. Within the United States (US), Hispanic children [4, 5] bear some of the largest burden of the childhood obesity epidemic, and the disparities gap is even greater among Hispanic children in rural communities [5]. Obesity prevention interventions have been shown to promote healthier weights among children, however, many take place in urban settings where resources are more available than rural settings [6-9]. To effectively address childhood obesity disparities among Hispanics, interventions that extend to resource-scarce rural communities are needed.

Obesity disparities in children may be attributed to a variety of factors; however, it is evident that the overall environment in which children, live, play, and interact has an effect on nutrition and physical activity (PA), and ultimately weight [10, 11]. Community, schools, peers, and family as well as the media and food/beverage industry are all entities that affect the rates of childhood obesity [10, 11]. For example, inaccessibility to fresh fruits and vegetables, through full service grocery stores and places to engage in PA were associated with higher body mass index (BMI) among elementary school children [11]. Thus, interventions that address both children and their environment, that is, multi-level intervention, may be conducive to healthier diet and PA, and ultimately healthier weights [12, 13].

Several intervention studies have successfully used multi-level approaches. They demonstrated that effective and sustainable interventions need to include community stakeholders, be guided by a theoretical framework, be longer than one school year, address multi-level predictors, and target children as they are beginning to establish their personal health behavior patterns [8, 9]. These successful studies were uniformly in urbanized settings where resources are more available than rural settings [6-8, 11]. Little research has been done to conduct and implement a community-based, multi-level intervention for rural Hispanic children.

A community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach builds on the complementary strengths and insights of community and academic partners to facilitate the development of interventions that are relevant for underrepresented groups and to maximize the effects of research addressing health disparities [14, 15]. Together We STRIDE (Strategizing Together Relevant Interventions for Diet and Exercise) is a community-based, weight loss trial for rural Hispanic children that uses a CBPR approach. The primary objective of the Together We STRIDE trial is to test the effectiveness of the comprehensive, community-wide multi-level intervention at reducing BMI z-scores among Hispanic children living in a rural area. Secondary objectives are to test the effectiveness of the intervention on healthier dietary patterns and promoting physical activity.

Methods

Together We STRIDE is a parallel quasi-experimental trial with the goal of recruiting 900 children aged 8-12 years to test the effectiveness of a comprehensive, multi-level intervention on children's BMI z-scores, dietary intake, and PA using repeated measures (at baseline, 6-months, and 18-months). The multi-level intervention include activities at the individual level, family level, school level, and community level.

2.1. Randomization

This quasi-experimental study includes two communities (one intervention and one comparison); both communities were matched in regards to town population, population density, number of elementary schools, and school student characteristics (standardized test scores, percentage of students eligible to receive free or reduced-price lunch, and school size).

2.2. Setting and population

This intervention study takes place in the Lower Yakima Valley of Eastern Washington State. In Washington State, much of the Hispanic population is concentrated in Yakima County. According to the 2011 census, the Lower Valley has a total population of about 100,000 people; roughly 65% are of Hispanic origin. Most of the Hispanic population in the Valley is Mexican-American (95%) [16].

2.3. Community-based participatory partnership

This study builds on more than 20 years of partnership between researchers and local community advisory boards (CABs), a group of community representatives who strive to promote health in their community. The CABs has collaborated with the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center researchers in areas of cancer prevention and control, diabetes prevention and control, pesticide control, and most recently on obesity prevention among children. The Together We STRIDE study CAB consists of a diverse group of community stakeholders including community-based organizations, school representatives, political figures, community health organizations, and community advocates. The Together We STRIDE study was built upon a community-wide needs health assessment of Hispanic children and their families in the lower Yakima Valley who identified childhood obesity as an issue of community interest. In addition, a pilot study that assessed a community-wide, multi-level weight intervention strategies for underserved Hispanic children and their families was conducted recently and helped form the intervention for this project. Consistent with CBPR principles [14], identification of the intervention, the study design, and proposed evaluation and dissemination plans were conducted collaboratively between community and academic partners. The study also includes two community subcontractors who are serving as community investigators. The application of the nine core CBPR principles delineated by Israel and colleagues are being followed [14].

2.4. Conceptual framework and Intervention

Together We STRIDE is grounded in the social ecological framework. The socio-ecological framework emphasizes the multiple spheres of influence on health and the dynamic interaction between the individual (child), family, schools, and community. Following a socio-ecological framework, the project is implementing a variety of activities at multiple levels of the child's environment. At the individual level, children will view comic books and posters that discuss the values of healthy eating and PA through story telling. At the family level, children and their families will participate in nutrition and PA classes to help them gain the skills to identify and prepare healthy meals and to participate in increased PA. At the school level, children will learn marketing practices of the food industry that leads to unhealthy eating and will learn how to incorporate PA during short intervals in their classrooms. Finally, at the community level, children will learn that the community cares about fostering healthy children. Taken together, the activities will have a synergy that provides children with constant, inescapable messages that healthy eating and PA are beneficial.

2.5. Interventions

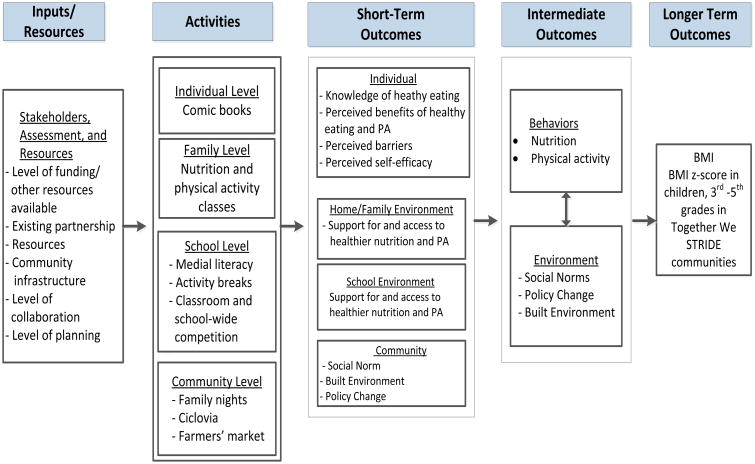

The Together We STRIDE logic model depicts the hypothesized pathways of influence of the intervention on the continuum of obesity related outcomes (Figure 1). The model illustrates how inputs, such as of the existing infrastructure and resources, may be related to the interventions, which may then be related to the short-term outcomes, including the children themselves, home/family environment, school, and the community. The short-term outcomes may be related to the intermediate outcomes of healthier nutrition and increased PA and ultimately will translate into healthier BMI.

Figure 1.

Together We STRIDE Logic Model

Individual Level

The Together We STRIDE study will distribute two annual comic books to children with targeted messages around healthy eating and engaging in PA. Stories will integrate the Go, Slow, and Whoa tool from Coordinated Approach To Child Health (CATCH) [17-21], a school-based program that promotes healthy eating and PA among children. This tool describes the list of healthful food choices (Go), those that should be taken in moderation (Slow), and food products to avoid (Whoa). The Go Slow and Whoa also will be adapted for PA. Two comic books will be distributed annually, one at fall and one in spring.

Family Level

This study will offer multi-generational nutrition and PA classes to the families of participants. Each series will be eight weeks long and will cover seven different topics and a review session. Examples of topics are 1) discussions about values and health, 2) types of PA and ways to incorporate them every day, and 3) discussions about My Plate. Each class session will be structured to include 1) an icebreaker activity, 2) nutrition and PA education, 3) cooking demonstration, 4) group PA, and 5) goal setting.

School Level

This project will collaborate with schoolteachers to integrate a media literacy education and PA breaks in their classrooms.

Media Literacy Education

Media literacy education involves the promotion of strategies to help students respond critically to advertising messages and images of food products [22-24]. Teachers will provide up to three 10 to 15 minute sessions per year on media literacy around food products.

PA Breaks

PA breaks are three- to 10-minutes PA sessions that can be incorporated into any classroom activity [25] and have been effective in promoting PA and improving academic performance [25]. Teachers will be encouraged to conduct four activity breaks per month.

School-level Challenge

The research staff will provide every participating classroom posters and stickers to track the media literacy activities and the PA breaks. At the end of the semester, the teacher and the classroom with the most media literacy education and PA breaks completed will receive a prize for their classroom.

Community Level

Community level activities will include a Family Night, Ciclovia, and plans to implement a farmers' market.

Family Night

A family night will serve as a platform to launch the intervention. The family night will consist of sharing a healthy meal together, learning about current activities around nutrition and PA in their community, engaging in discussion about community issues related to obesity, and participating in a group PA.

Ciclovia

The Ciclovia is an event where community members “claim the streets” for PA by obtaining a permit from the city to close the streets. This event will take place once a year. The CAB will work to select the location, to obtain a permit from the city to close the streets, recruit community volunteers to engage the community members in activity hubs for adults (e.g., aerobics, yoga, and Zumba) and children (e.g., obstacle course, low ropes course, mini Olympics, hula hoops competition or free play).

Farmers' Market

The community-academic partners will meet with the Farmer Market Association, representatives from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, local community organizations, and other businesses to start a Farmer's Market in the intervention community, which currently does not have one. The partners will discuss the concept, location, identification of key constituents, and logistical issues with the goal of starting the market during the intervention period.

2.6. Comparison Group

Children who attend schools in the comparison community will not receive the multilevel intervention. Instead, they will receive two generic newsletters annually. The newsletter will be directed at children and will contain information about benefits of healthy eating and engaging in PA, goal setting for children, activities to engage the families, and a list of publicly available resources and information on the internet. The distribution of the newsletters will coincide with the distribution of the comic books at schools (fall and spring).

2.7. Participant eligibility and recruitment

Students come from the two matched communities on population density, number of elementary schools, and school student characteristics (standardized test scores, percentage of students eligible to receive free or reduced-price lunch, and school size). Eligible children include Hispanic children in grades 3-5 (ages 8-12) who attend elementary schools in our intervention and comparison communities. The project excluded children with disabilities that prevent them from participating in interviews, PA, or had special diets due to a medical condition.

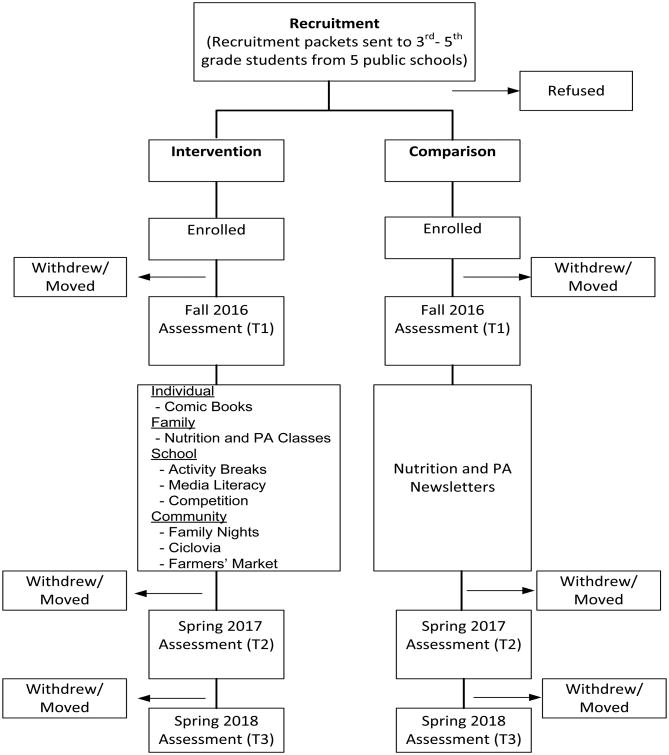

We will recruit eligible children through five elementary schools (3 schools from the intervention community and 2 schools from the comparison community) (Figure 2). A packet containing information about the study, parent consent form, and student assent form will be distributed to children in grades 3 - 5 through their teachers. At the front of the packet, a note will be attached inviting parents to attend an information session about the study, and a chance to receive free movie tickets if packets are returned within two weeks. The parental consent will include a box at the end that could be checked if they wanted to consider having their children in a subgroup that included additional measurements (see data collection below). When the consent forms (parent informed consent and child written assent) are received for an eligible child, the participant will be deemed enrolled. A second round of packets with the same recruitment materials will be distributed for students who do not return their packets in the first round. Three reminder calls (using schools' robot calls system) will be made to non-respondents in two weeks.

Figure 2.

Consort Diagram.

Parents who expressed interest in enrolling their children for the subgroup sample will be followed by phone to confirm their participation in the additional measurement.

2.8. Data Collect ion

The study will use two data collection protocols, one that collects height and weight (General protocol) and demographics and another that collects more detailed dietary and PA measurements on a subsample of participants who also are measured for height and weight (Enhanced protocol).

General protocol

Data collection using this protocol will be conducted at schools (height and weight measurement). Assessment will be done by grade level. Six data collection stations will be set up during the data collection date to measure six students at the same time. Each station will have a large color poster to block the weight information from the scale for confidentiality and to give students privacy. The students who are absent on measurement days will be contacted by phone and height and weight will be completed at a place of their preference (at our site office or participants' residence). Participants will receive a small gift (worth $3) after the measurement.

Enhanced protocol

Additional assessment for this group will include dietary patterns using Dietary Screener Questionnaire (DSQ) [26] and the use of accelerometers to assess PA for seven consecutive days [27]. Parents will be contacted to schedule an in-person visit by our staff community health workers for these additional measurements, and such data collection will occur at the place of participants' preference (at our office site or participants' residence). Participating students will receive a $15.00 gift card at the completion of the questionnaire and wearing the accelerometer. The on-person visits will follow rapidly after collection of the primary outcome (height and weight) measurements and six months and 18-month assessments will follow

2.9. Primary Outcome

The primary outcome is BMI z-scores. BMI will be calculated using the measured height and weight. Participants will be weighed in light clothing (without shoes) with the use of a portable Tanita WB-110A digital body weight scale (TanitaCorporationAmerica, Arlington Heights, IL, 2001) to the nearest 0.1 kg. Height will be measured with the use of a Charder HM200P Portstad Portable Stadiometer (Charder Medical, Taiwan, ROC, 2007) to the nearest 0.2 cm. Students in 3rd-5th grade levels who have agreed to the general protocol will be measured for height and weight at baseline, 6 months, and 18 months. The primary study outcome for all participants is the change in BMI z-scores between the intervention and the comparison groups.

2.10. Secondary Outcomes

Dietary Pattern

The study will use the Dietary Screener Questionnaire (DSQ) developed by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (interviewer-administered version) [26]. The participants will be asked to report their intakes of selected foods consumed over the past 30 days by stating the number of times per day, week, or month the food was consumed. Items will include fruits and vegetables; dairy; sugar-sweetened beverages; other energy-dense foods of minimal nutritional value (e.g., fried potatoes, chocolate/candy, donuts/sweet rolls, cookies/cakes/pies, ice cream/frozen desserts, chips/crackers); and whole grains. Publicly available NCI-generated scoring algorithms will be used by the research team to convert respondent frequencies of intake to estimated quantities of select food groups and nutrients, based on age- and gender-specific 24-hour dietary recall portion size data from NHANES data [28].

Physical Activity

PA levels as measured using the ActiGraph GT3X-BT accelerometer. This device assesses body movement on three orthogonal axes and raw data are computed into counts per unit time or “epoch”. We will download and evaluate the raw data in 15-second (s) epochs, since prior research has shown that a 15-s epoch length can reliably capture moderate, vigorous, and sedentary activity in children ages 7-11 years [27]. Counts per epoch will be used to classify time spent in moderate-to-vigorous activity (MVPA) and sedentary (SED) activity based on standardized, age-appropriate cut-point values [29].

2.11. Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis will be a t-test comparing the change in BMI z-score from baseline to follow-up by intervention (community) status. The analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes are well powered. The study has 80% power to detect a difference of 0.23 in change in BMI z-scores in the intervention group compared to the comparison group and to detect 10 minute difference in MVPA; we expect to see an increase in fruit and vegetable consumption. Analysis will be conducted using linear regression with change in the BMI z-score as the dependent variable and intervention arm (community) as the independent covariate. Hierarchical linear mixed effects regression methods will be used to account for potential intra-school and intra-family correlations. Schools will be nested within community, families within schools and students within families. No adjustment for hierarchical community effect will be needed, since this is the intervention covariate. Baseline characteristics will be evaluated for differences between the two communities (intervention and comparison) and any significant differences will be adjusted for in all analysis. Finally, all longitudinal data will be used to further evaluate changes in BMI z-scores over time by the intervention arm. For these analyses, time point will be nested within individual and appropriate hierarchical models will be used with appropriate adjustments using the methods described above for potential intra-individual auto-correlation. Including BMI z-score data from all time points will likely provide additional power in detecting differences in changes in BMI z-score over time by study arm.

2.12. Dissemination Plan

Dissemination of research findings to the participating communities is an essential component of the CBPR approach [14]. In order to continue the inclusive and transparent nature of this research effort, the community and academic investigative team will work together to create and develop a community organizing strategy for providing timely and useful information to the communities through community forums, resource guides, and information sessions. Project results will be disseminated to academic audiences through scientific manuscripts, conferences, and the intervention manual with program materials will be useful for future practitioners.

Summary

The Together We STRIDE is the culmination of over 20 years of collaborative work between community and academic partners in a rural area, whereby the community identified the issue of obesity, co-led pilot studies upon which the Together We STRIDE was built, and co-created the design of the current large-scale trial. The CBPR approach enabled the incorporation of community inputs throughout the intervention study, which answers the call for cultural sensitivity when designing community-based interventions, shortens the pipeline for intervention dissemination, and increases potential for integration of the intervention in the community and sustainability [14].

The Together We STRIDE is innovative in many ways. First, this study is focused on a rural setting. Past multi-level interventions that aim to reduce obesity focused mainly in schools and urbanized settings where resources are more available than in rural settings [6, 7, 30-33]. This study will help identify successful multi-level intervention components and implementation processes in rural settings. Second, although the study focus is on children, our intervention will be designed with a multi-generational approach and will target multi-generational participants (children, parents, and grandparents) in order to change the children's social environment. The Hispanic community has been characterized as close-knit and reciprocal toward members of extended families [34]. Therefore, the multi-level and the multi-generational approach will achieve a high level of synergy, and the intervention messages on healthy lifestyle choices will permeate all levels of the community. Finally, the study findings have potential for translational impact into policy and practice. Schools have been identified as settings with extraordinary influence to promote children's nutrition and PA through policy and practice change. Our study involves strong collaboration with schools and includes intervention activities that can be embedded easily into already existing school curricula. The findings of this study will provide the evidence that can facilitate policy decisions and best practices at schools by identifying effective school-level intervention activities and processes that can facilitate adoption of the intervention [35].

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (grant number U01 MD010540).

Abbreviations

- CBPR

Community-based participatory research

- STRIDE

Strategizing Together Relevant Interventions for Diet and Exercise

- PA

Physical Activity

- MVPA

moderate-to-vigorous activity

- SED

sedentary

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- DSQ

Dietary Screener Questionnaire

- CAB

Community Advisory Board

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Footnotes

Competing Interests: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Linda K. Ko, Division of Public Health Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Department of Health Services, University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, WA.

Eileen Rillamas-Sun, Division of Public Health Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Sonia Bishop, Division of Public Health Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA.

Oralia Cisneros, Sunnyside School District, Sunnyside, WA.

Sarah Holte, Division of Public Health Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA.

Beti Thompson, Division of Public Health Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA.

References

- 1.Flores G, et al. The health of Latino children: urgent priorities, unanswered questions, and a research agenda. JAMA. 2002;288(1):82–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau M, Lin H, Flores G. Racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care among U.S. adolescents. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(5):2031–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman DS, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr. 2007;150(1):12–17 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the united states, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administratin, and M.a.C.H. Bureau. The Health and Well-Being of Children in Rural Areas: A Portrait of the Nation, 2011-2012. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chomitz VR, et al. Healthy Living Cambridge Kids: a community-based participatory effort to promote healthy weight and fitness. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18 Suppl 1:S45–53. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Economos CD, et al. Shape Up Somerville two-year results: a community-based environmental change intervention sustains weight reduction in children. Prev Med. 2013;57(4):322–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kropski JA, Keckley PH, Jensen GL. School-based obesity prevention programs: an evidence-based review. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(5):1009–18. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Summerbell CD, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 20053:CD001871. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll-Scott A, et al. Disentangling neighborhood contextual associations with child body mass index, diet, and physical activity: the role of built, socioeconomic, and social environments. Soc Sci Med. 2013;95:106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lovasi GS, et al. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:7–20. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knowlden AP, Sharma M. Systematic review of school-based obesity interventions targeting African American and Hispanic children. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(3):1194–214. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waters E, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 201112:Cd001871. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Israel BA, et al. Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research principles. Community-based participatory research for health. 2003:53–76. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viswanathan M, et al. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 200499:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Census Bureau. Selected Population Profile in the United States: 2011 American Community Surcey 1-Year Estimates. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoelscher DM, et al. Dissemination and Adoption of the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH): A Case Study in Texas. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2001;7(2):90–100. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200107020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luepker RV, et al. Outcomes of a field trial to improve children's dietary patterns and physical activity: The child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health (catch) JAMA. 1996;275(10):768–776. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530340032026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osganian SK, Parcel GS, Stone EJ. Institutionalization of a School Health Promotion Program: Background and Rationale of the Catch-on Study. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30(4):410–417. doi: 10.1177/1090198103252766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perry CL, et al. The Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH): Intervention, Implementation, and Feasibility for Elementary Schools in the United States. Health Education & Behavior. 1997;24(6):716–735. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perry CL, et al. School- based cardiovascular health promotion: The child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health (CATCH) Journal of School Health. 1990;60(8):406–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1990.tb05960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Byrd-Bredbenner C, Grasso D. What is television trying to make children swallow?: content analysis of the nutrition information in prime-time advertisements. Journal of nutrition education. 2000;32(4):187–195. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chernin A. The Effects of Food Marketing on Children's Preferences: Testing the Moderating Roles of Age and Gender. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2008;615(1):101–118. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hindin TJ, I, Contento R, Gussow JD. A media literacy nutrition education curriculum for head start parents about the effects of television advertising on their children's food requests. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104(2):192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prevention, C.f.D.c.a. The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Includign Physical Education, and Academic Performance. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Cancer Institute. Dietary Screener Questionnaire in the NHANES 2009-10. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edwardson CL, Gorely T. Epoch length and its effect on physical activity intensity. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2010;42(5):928–934. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c301f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Cancer Institute. Dietary Screener Questionnaire (DSQ) in the NHANES 2009-10: Data Processing & Scoring Procedures. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trost SG, et al. Comparison of accelerometer cut points for predicting activity intensity in youth. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2011;43(7):1360–1368. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318206476e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de la Torre A, et al. Niños Sanos, Familia Sana: Mexican immigrant study protocol for a multifaceted CBPR intervention to combat childhood obesity in two rural California towns. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1033. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kipping RR, et al. Effect of intervention aimed at increasing physical activity, reducing sedentary behaviour, and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in children: Active for Life Year 5 (AFLY5) school based cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 2014;348 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tuuri G, et al. “Smart Bodies” school wellness program increased children's knowledge of healthy nutrition practices and self-efficacy to consume fruit and vegetables. Appetite. 2009;52(2):445–51. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, et al. Obesity prevention in low socioeconomic status urban African-american adolescents: study design and preliminary findings of the HEALTH-KIDS Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(1):92–103. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vega WA. Hispanic Families in the 1980s: A Decade of Research. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1990;52(4):1015–1024. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oxman AD, et al. SUPPORT Tools for evidence-informed health Policymaking (STP) 1: What is evidence-informed policymaking? Health Research Policy and Systems. 2009;7(1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-7-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]