Abstract

Background

Strong feelings about and enthusiasm for nursing care are reflected in nurses’ thoughts and behaviors in clinical practice and affect their profession. This study was conducted to identify the characteristics of core values in nursing care based on the experiences of nurses engaged in neonatal nursing through a process for recognizing the conceptualization of nursing.

Methods

We conceptualized nursing care in 43 nurses who were involved in neonatal nursing using a reflection sheet. We classified descriptions on a sheet based on the Three-Staged Recognition scheme and analyzed them using a text-mining approach.

Results

Nurses involved in neonatal nursing recognized that they must take care of the “child,” “mother,” and “family.” Important elements of nursing in nurses with less than 5 years versus 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience were classified into seven clusters, respectively. These elements were mainly related to family members in both groups. In nurses with less than 5 years of experience, four clusters of one-way communication by nurses were observed in the analysis of the key elements in nursing. On the other hand, five clusters of mutual relationships between patients, their family members, and nurses were observed in nurses with 5 or more years of experience.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the core value of nurses engaged in neonatal nursing is family-oriented nursing. Nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience understand patients and their family members well through establishing relationships and providing comfort and safety while taking care of them.

Keywords: caring, neonatal nursing, recognition process, reflection, text-mining

Neonatal nursing provides continuous comprehensive support for not only newborns but also their parents and family members before, during, and after birth. Nurses are responsible for health promotion in newborns and their families. They are pioneers in developing and sharing assessments of health promotion.1 Nurses involved in neonatal nursing can serve as experts in clinical practice through recognition of their responsibilities based on their experiences and individual perspectives on nursing.

Nurses make an effort to provide the best nursing care for patients instead of just simply providing care based on his or her background and proper clinical judgment according to patient’s condition. Strong feelings about and enthusiasm for nursing care in nurses are reflected in their thoughts and behaviors in clinical practice, which can affect their profession. In other words, a perspective or thought on nursing care (view on nursing) can affect a nurse’s behavior. Value and belief-based behaviors most strongly contribute to the quality of clinical practice in nurses with 5 or more years of experience.2, 3 However mid-career nurses with 5 or more years of nursing expertise are likely to reach a plateau.4 It has also been reported that nurses have poor clinical judgment regardless of nursing experience if they work in a different field of nursing in which they have no experience.5 Practical skills are thought to be based on the consistency of thoughts and behaviors. Skill quality can be improved only by the development of communities of practice.6 Habits of thought and action and thinking during actions is necessary for becoming an expert.7

Jinda6 created a worksheet that conceptualizes the Theory on Three-Staged Recognition and their Mutual Commitmentb established by Shoji.8 Three-Staged Recognition is comprised of sensual, presentative, and conceptual recognition.6, 8 This worksheet is useful for identifying key nursing elements for nurses through an inner dialogue as they write down their nursing experiences. In this study, we focused on elucidating the key values of neonatal nurses as a whole instead of their each nurse’s individual progress through the different stages of recognition. We accomplished this by determining the characteristics of each stage of recognition (sensuous, presentative, conceptual) through text-mining analysis of the type, frequencies, and relationship amongst of words in the used by nurses’ to answer questions responses. We conducted this study to identify the characteristics of core values in nursing care based on the experiences of nurses engaged in neonatal nursing through a process of recognizing nursing core values obtained using a reflection9–11 sheet.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was designed as a hypothesis-exploring investigation using a text-mining tool.

Study subjects

This study included a total of 43 nurses and midwives involved in neonatal nursing at the Comprehensive Center for Perinatal Medicine (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and Growing Care Unit), Tottori University Hospital.

Data collection

Data were collected between April 1, 2015 and March 31, 2017. We prepared an original six-item reflection worksheet based on the conceptualization worksheet for nursing created by Jinda.6 Subjects looked back on their nursing experiences and replied to the following questions on the reflection worksheet on their own: Can you describe some unforgettable cases?; Why do you remember them?; What did you think you should do when you provided nursing to cases like this?; and What is the most important element of nursing for you?

For presentative recognition, in order to determine the factors involved in the transition from recognizing to performing ideal patient care, we asked “What were some obstructive and promotional factors in nursing when you provided nursing care to unforgettable cases?” Similarly, in order to determine the key value of nursing in conceptual recognition, we asked “What is the key element of nursing?” Subjects’ answers were written down on the reflection sheet by a researcher. Questions about obstructive and promotional factors in nursing measured the development of presentative recognition. Similarly, questions about the essence of nursing measured the development of conceptual recognition through abstraction of important elements in nursing.

We classified the descriptive content of the reflection worksheet based on Three-Staged Recognition in nursing practice as presented by Jinda.6

We classified “Can you describe some unforgettable cases?” and “Why do you remember them?” into sensuous recognition.c Sensuous recognition refers to the stage in which a person interacts with a phenomenon using the five senses. We prepared two questions to clarify how nurses felt about “unforgettable cases.”

We classified “What did you think you should do when you provided nursing to unforgettable cases?” and “What were obstructive and promotional factors in nursing when you provided nursing care to unforgettable cases?” into presentative recognition.d Presentative recognition refers to the stage in which a person makes inferences about a phenomenon.

We prepared two questions to clarify the thoughts of nurses about “unforgettable cases.”

We classified “What is the most important element of nursing for you?” and “What is the key element of nursing?” into conceptual recognition.e Conceptual recognition refers to the stage in which a person abstracts the essence of a phenomenon. Thus, we prepared two questions to clarify the thoughts of nurses on the essence of “unforgettable cases.”

With respect to subject characteristics, we asked about age, sex, years of nursing experience, and years of neonatal nursing experience on the reflection sheet filled out by subjects.

Analytical method

Descriptive content on the reflection sheet was entered as text data and analyzed through a text-mining approach. The target of reflection is an informational and narrative written document that tells a story or describes an episode.12 The text-mining approach is used with written materials. It is considered to be useful in exploratory, hypothesis-testing, and hypothesis-generating studies.13 In this study, we quantitatively analyzed the associations between words in the written materials on the reflection sheet using a text-mining software (TMS) for graphical representation and visualization. We used Text Mining Studio, version 5.0 (NTT DATA Mathematical Systems, Tokyo, Japan).

Data cleaning

The descriptive content, age, sex, years of nursing experience, and years of neonatal nursing experience on the reflection sheet were entered into a new spreadsheet. Next, we checked the text data and revised any typographical or conversion errors, grammatically incorrect words and phrases, and words not listed in the dictionary. Japanese is an agglutinative language. The software partitions a sentence into terms according to an on-board dictionary for morphological analysis. To prevent inaccurate partitioning, terms that were not included in the original dictionary were registered in a forced choice list of morphological elements prior to the morphological analysis. We also corrected the original data while retaining its authenticity. The pretreated file was converted into a comma-separated values (CSV) format and spreadsheet data was retrieved in the TMS for morphological analysis. After confirming the content of the text, we compiled and reviewed the user dictionary for writing with a space between Japanese synonyms and complex words. We considered it difficult to divide complex medical terms that must be treated as a noun into a clause in the morphological analysis and registered these terms in the user dictionary.

Analysis of Three-Staged Recognition and their Mutual Commitment using the text-mining approach

Three-Staged Recognition

In nurses, conceptualization of nursinga develops through a deep understanding of nursing with conceptual recognition acquired after sensuous and representational recognition. In this study, we focused on elucidating the key values of neonatal nurses as a whole instead of each nurse’s individual progress through the different stages of recognition. We accomplished this by determining the characteristics of each stage of recognition (sensuous, presentative, conceptual) through text-mining analysis of the type, frequency, and relationship among words in the nurses’ responses.

In other words, we analyzed the nurses’ perceptions through sensuous recognition, the nurses’ inferences with respect to “unforgettable cases” based on their perceptions through presentative recognition, and the essence of nurses’ recognition in “unforgettable cases” through conceptual recognition. To determine the characteristics of sensuous recognition, we included nurses in direct contact with their “unforgettable cases” in our study. We examined their feelings to see how they developed into the presentative recognition stage.

In addition, we compared the results of nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience and those with less than 5 years’ experience based on previous studies2–4 to identify the characteristics of core values in nursing care in neonatal nurses. We used these groups for comparison because the fifth year of neonatal nursing is considered to be the period in which the experiences of nurses can affect the process of nursing.

Analysis of sensuous recognition

With respect to unforgettable cases, we identified the source subject. For “Why do you remember these cases?”, we considered the background emotions of nurses and classified these into negative feelings (sad, painful, tough, and shocked) and positive feelings (glad, happy, satisfied, and useful). We extracted frequently used parts of speech based on feature expression analysis and calculated the frequency of commonly used terms on the reflection sheet for “unforgettable cases” to clarify the patient source and the nurse’s impression of the patient. For the frequency of specific words and the combination of modified source words and modifying words, we classified terms as a noun, verb, and verb formed by adding “suru” to a noun to clarify the source subject’s behavior. For example, the verbs “nyuuin-suru” and “menkai-suru” were counted as the nouns “nyuuin” and “menkai.”

Analysis of presentative recognition

We defined featured common nouns based on persons who were commonly observed in the sensuous recognition analysis. We then conducted a featured word analysis with the minimum reliability value set at 60% and a co-occurrence frequency of ≥ 2 per document. To analyze the types of words and subjects that co-occurred with the nouns selected based on persons commonly observed in the featured word analysis, words obtained from the featured word analysis were set as nodes according to word frequency. We then connected nodes of more commonly co-occurring words with an edge and prepared a network diagram. In the diagram, we used a circle for a node and a line for an edge. The size of node circles represents the frequency of words and the thickness of the line shows the frequency of co-occurrence of connected words.

Analysis of conceptual recognition

We analyzed the word relationship network for “What is the most important element of nursing for you?” and “What is the key element of nursing?” by extracting co-occurring words in the entire text to find words with strong associations for clustering. To extract co-occurring words, we set a reliability value of 100% for probability and frequency and ≥ 2 co-occurrences as a rule between words and between words and subjects. A cluster represents a group of nodes connected by edges. The composition of a cluster with independent nodes is shown as a group of topics.

Ensuring study reliability and validity

With respect to the external validity of the data, researchers participating in this study checked the descriptive content on the reflection sheet for any mistakes. We confirmed the reliability and internal validity of outputted results under the supervision of experts in text-mining during analysis.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted with approval from the Ethics Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine at Tottori University (No. 1833).

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

Age ranged from 23 to 53 years (mean: 33.1 years), years of nursing experience ranged from less than 1 to 29 years (mean: 9.7 years), and years of neonatal nursing experience ranged from less than 1 to 14 years (mean: 4.1 years). Nineteen nurses had 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience; they had between 6 and 29 years (mean: 13.3 years) of nursing experience overall. Twenty-four nurses had less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience and between less than 1 and 26 years (mean: 7.1 years) of nursing experience overall (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants (n = 43)

| Number of patients, n | 43 | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 42 (97.6) | |

| Male | 1 (2.3) | |

| Type of license, n (%) | ||

| Nurse | 34 (79.0) | |

| Midwife | 9 (20.9) | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 33.1 ± 8.0 | |

| Years of nursing experience, mean ± SD | 9.8 ± 7.8 | |

| Years of experience in neonatal nursing, mean ± SD | 4.5 ± 3.9 | |

Analysis of word frequency

The analysis of word frequency for the descriptive content on the reflection sheet revealed that the most commonly used noun was a general noun and all verbs were content verbs (no suffix form or non-content verbs were observed) (Table 2). Sensuous recognition included more words than other representational recognition or conceptual recognition, regardless of whether they had 5 or more years of nursing experience or not. Fewer words were used with some stages.

Table 2.

Reflection text results

| Nurses with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience (n = 24) | Nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience (n = 19) | |||||

| Three-Staged Recognition | Sensuous recognition | Presentative recognition | Conceptual recognition | Sensuous recognition | Presentative recognition | Conceptual recognition |

| Average line length (number of characters) | 333.6 | 271.9 | 105.9 | 396.5 | 282.1 | 105.4 |

| Total number of sentences | 197 | 163 | 87 | 178 | 129 | 63 |

| Average sentence length (number of characters) | 87.6 | 71.9 | 57.7 | 85.3 | 76.2 | 63.7 |

| Number of words | 1491 | 1182 | 484 | 1422 | 959 | 381 |

| Number of word types | 929 | 688 | 321 | 952 | 599 | 277 |

| Noun | 934 | 732 | 327 | 914 | 626 | 256 |

| Common noun | 518 | 337 | 167 | 471 | 289 | 136 |

| Pronoun | 41 | 51 | 10 | 46 | 40 | 9 |

| Adverbial noun | 75 | 28 | 4 | 47 | 26 | 6 |

| Verb formed by adding “suru” to a noun | 198 | 185 | 102 | 261 | 160 | 72 |

| Adjective verb stem | 47 | 84 | 32 | 42 | 68 | 25 |

| Other | 55 | 47 | 12 | 47 | 43 | 8 |

| Verb | 368 | 295 | 120 | 338 | 220 | 92 |

| Stand-alone verb | 368 | 295 | 120 | 338 | 220 | 92 |

| Part of speech other than noun or verb | 189 | 155 | 37 | 170 | 113 | 33 |

| Stand-alone adjective | 48 | 20 | 3 | 39 | 35 | 4 |

| Common adverb/postpositional particle connection | 75 | 65 | 18 | 80 | 48 | 10 |

| Other part of speech | 66 | 70 | 16 | 51 | 30 | 19 |

Recognition process in the conceptualization of nursing

Sensuous recognition

With respect the source subject of “unforgettable cases,” the most commonly observed source subject was the mother, with 6 answers (31.5%) in nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience and 11 (45.8%) answers in those with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience. Many answers for “Why do you remember these cases?” included negative feelings, which were observed in 11 answers (57.8%) in nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience and 21 (87.5%) answers in nurses with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience.

When placed in descending order of frequency, nouns, verbs formed by adding “suru” to a noun, and verbs were observed in up to the top 96 items in the list in nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience and up to the top 97 items in those with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience. The most common noun, verb formed by adding “suru” to a noun, or verb in the top 20 items was observed in 53% and 51% in nurses with 5 or more and less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience, respectively. These words were included in the top 45 words in both groups, accounting for 75% of all words. The general nouns of “child,” “mother,” “family,” “parents,” “father,” “patient,” and “nurse” (referring to the study participant) were commonly used (Table 3). “Think” and “see” were observed more often in nurses with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience and “feel” was observed more often in nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience. “Caregiving” was not observed in nurses with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience.

Table 3.

Parts of speech for “unforgettable cases”

| Part of speech | Detailed part of speech | Word(s) | Nurses with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience (n = 24) | Nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience (n = 19) |

| Noun | Common | Child | 44 | 42 |

| Mother | 46 | 48 | ||

| Family | 12 | 39 | ||

| Parents | 11 | 10 | ||

| Patient | 10 | 5 | ||

| Father | 6 | 9 | ||

| Nurse | 8 | 5 | ||

| Feeling | 5 | 10 | ||

| Voice | 14 | 1 | ||

| Caregiving | 0 | 10 | ||

| Informed consent | 7 | 3 | ||

| Verb formed by adding “suru” to a noun | Visitation | 18 | 5 | |

| Description | 5 | 7 | ||

| Hospitalization | 8 | 4 | ||

| Stand-alone verb | Think | 15 | 9 | |

| See | 12 | 9 | ||

| Say | 8 | 12 | ||

| Consider | 7 | 9 | ||

| Feel | 2 | 13 | ||

| Do | 4 | 10 | ||

| Understand/Not understand | 10 | 4 | ||

| Listen | 9 | 4 |

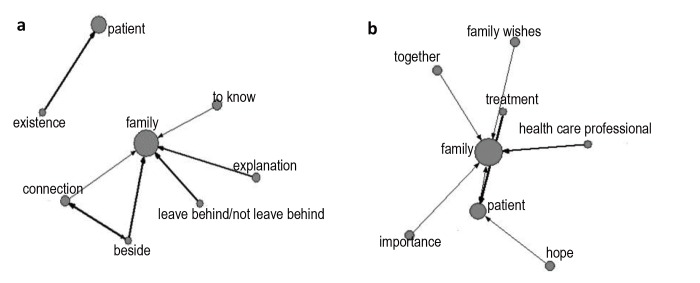

Presentative recognition

We analyzed the common nouns commonly observed in the sensuous recognition analysis, including “child,” “mother,” “family,” “parents,” “father,” “patient,” and “nurse.” Nurses with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience stood by the “side” of the “family” and recognized the importance of “explanation” to the family. In addition, they acknowledged the “existence” of the “patient” and recognized that support was required for them not to be left behind by their “family” (Fig. 1a). Nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience confirmed “family wishes” and recognized the “hope” of a “patient” should be supported by a “medical person.” In the network diagram showing the co-occurrence between nodes and edges in the featured word analysis, nurses with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience made a distinction between “patient” and “family” and nodes for “patient” and “family” were different. On the other hand, “patient” and “family” were combined in nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience and a co-occurrence relationship was observed; nodes with “patient” and “family” were connected by edges (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Co-occurrence network diagram for presentational recognition.

a: Nurses with less than 5 years of experience in neonatal care. b: Nurses with 5 or more years of experience in neonatal care.

Text-mining analysis of terms with a minimum reliability of 60% and a co-occurrence frequency ≥ 2 for each target: “mother,” “child,” “family,” “parents,” “patient,” “nurse,” and “father.” The size of the node reflects the term’s frequency. An edge → is a line connecting a node with other nodes. The direction of the arrow indicates that terms in the bottom node frequently co-occur with terms in the top node. Bidirectional arrows indicate that both terms co-occur frequently and interactively. The thickness of the line indicates a co-occurrence relationship and represents the frequency of co-occurrence.

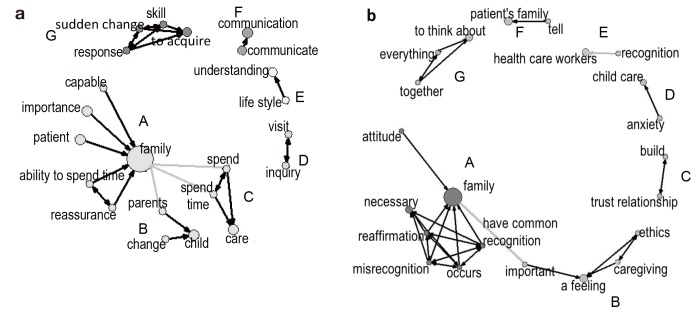

Conceptual recognition

With respect to “What is the most important element of nursing care for you?” seven clusters were observed in nurses with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience (Fig. 2aA–G): “to cherish the time the family and patient spend together,” “informing the family of changes in the child’s condition,” “time spent in nursing care,” “behaviors during visits,” “understanding the patient’s lifestyle,” “communication,” and “actions during emergencies.” Seven clusters were observed in nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience (Fig. 2bA–G): “reconfirmation and having a common perspective to prevent discrepancies between families and nurses,” “ethics and feelings are important in caregiving,” “establishing a relationship of trust,” “responding to parenting anxiety,” “recognition of medical staff,” “informing the patient’s family,” and “thinking together.”

Fig. 2.

Co-occurrence network diagram for “what is the most important element of nursing for you?”

a: Seven clusters were extracted for nurses with less than 5 years of experience in neonatal care: (A) to cherish the time spent by the family and patient, (B) informing the family of changes in the child’s condition, (C) time of care, (D) behaviors during visits, (E) understanding lifestyle, (F) communication, (G) actions during emergencies. b: Seven clusters were extracted for nurses with 5 or more years of experience in neonatal care: (A) reconfirmation and having a common perspective to prevent discrepancies between families and nurses, (B) ethics and feeling for caregiving are important, (C) establishing a relationship of trust, (D) response to parenting anxiety, (E) recognition of medical staff, (F) inform the patient’s family, (G) thinking together.

Network diagram of terms associated with “what is the most important element of nursing for you?” with 60% reliability and a co-occurrence frequency ≥ 2. The number of clusters was confirmed that no nodes are independent. The size of the node indicates the term’s frequency. An edge → is a line connecting a node with other nodes. The direction of the arrow indicates that terms in the bottom node frequently co-occur with terms in the top node. Bidirectional arrows indicate that both terms co-occur frequently and interactively. The thickness of the line indicates a co-occurrence relationship and represents the frequency of co-occurrence.

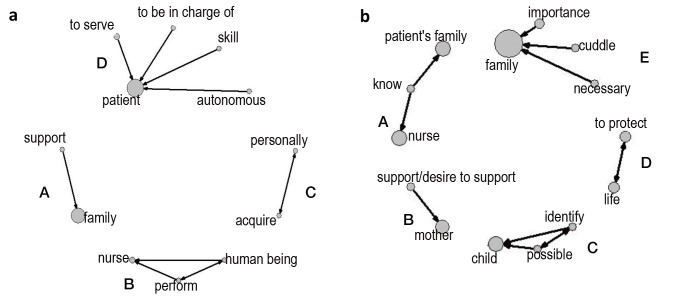

For “key element of nursing,” four clusters of one-way communication by nurses were observed in nurses with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience (Fig. 3aA–D): “supporting a family,” “personal role in nursing,” “learning a skill,” and “nursing technique.” On the other hand, five clusters of mutual relationships between patients, their family members, and nurses were observed in nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience (Fig. 3bA–E): “understanding the patient’s family,” “supporting the mother,” “seeing what is possible,” “protecting patients’ lives,” and “staying with the family.”

Fig. 3.

Co-occurrence network diagram for “the key element of nursing.”

a: Four clusters were extracted for nurses with less than 5 years of experience in neonatal care: (A) supporting a family, (B) personal role in nursing, (C) leaning a skill, (D) nursing technique. b: Five clusters were extracted for nurses with 5 or more years of experience in neonatal care: (A) understanding the patient’s family, (B) supporting the mother, (C) seeing what is possible, (D) protecting patients’ lives, (E) staying with the family.

Text-mining analysis of terms with 100% reliability and a co-occurrence frequency ≥ 2. The number of clusters was confirmed that no nodes are independent. The size of the node indicates the term’s frequency. An edge → is a line connecting a node with other nodes. The direction of the arrow indicates that terms in the bottom node frequently co-occur with terms in the top node. Bidirectional arrows indicate that both terms co-occur frequently and interactively. The thickness of the line indicates a co-occurrence relationship and represents the frequency of co-occurrence.

DISCUSSION

We analyzed words and phrases in nursing using a reflection worksheet with a text-mining approach. We classified the descriptive content into the three stages of recognition to facilitate text-mining analysis. Central values for these thoughts were regarded as conceptual recognition, and “What is the most important element of nursing for you?,” and “What is the key element of nursing?” were asked thereafter. In this study, care activities mainly directed towards the family were part of conceptual recognition. The core value of nurses engaged in neonatal nursing is family-oriented nursing.

Only one-way communication from nurses to those receiving care was found in nurses with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience, while a mutual relationship between those receiving care and nurses was observed among nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience in conceptual recognition. Previous studies2, 3 found that the quality of nursing practice is most strongly associated with behaviors based on nurses’ views on and beliefs on nursing if nurses had provided clinical nursing care for 5 or more years, because their clinical experiences and deductive inferences are united.2, 3 Based on the results from the present study, it is also thought that nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience can provide nursing care based on their conceptualization of nursing. They had relationships with patients, their family members, and other nurses that consisted of presentative recognition. In addition, it was suggested that they recognized caring,14–16 which involves making family and patients comfortable and safe as part of conceptual recognition in nursing practice. This study revealed that nurses with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience engage in one-way communication, suggesting that they cannot provide meaningful care. Benner17 reported that nurses noticed problems that patients were facing only if they have strong convictions about improving nursing practice. It is thought that nurses with less than 5 years of neonatal nursing experience can conceptualize nursing if they recognize what kind of impact their nursing care has on patients and their families and imagine specific relationships among nurses, patients, and their families in nursing practice as part of presentative recognition.

Conceptualization of nursing is a process of abstraction in order to identify the structure and nature of nursing by getting an overview of complex and dynamic phenomena. This is also a process of looking back on previous nursing experiences and verbalization of these experiences.6 However, there are limitations to nurses looking back on experiences and verbalizing them. It is also not easy to control the process of the Three-Staged Recognition and their Mutual Commitment, which includes sensuous, presentative, and conceptual recognition. Benner7 recommended using a narrative approach to understand experiential learning content. According to Benner, we can understand clinical practice deeply by not only looking back on clinical experiences by ourselves but by also telling others about these experiences using a narrative approach. Establishing an experiential learning environment for nursing using a narrative approach allows nurses to think about nursing care deeply during the processes of going up and down the Three-Staged Recognition, abstraction, and realization for their previous experiences. Repeating the process of conceptualizing nursing by looking back on a nurse’s experiences and relating these experiences to others using the narrative approach, can allow for the establishment of an original view on nursing and lead to better nursing care with recognition and corresponding actions.

This study has several limitations. We did not analyze each nurse’s process of moving through Three-Staged Recognition, from sensual to conceptual, with respect to “unforgettable cases.” Thus, we cannot comment on the relationship between these stages. Reflection records are subjective descriptions of a nurse’s experiences and these records can be affected by writing skill and expression ability. In this study, researchers took the part of the listener and supported nurses as they conceptualized nursing. This support may have impacted what nurses thought and said.

In conclusion, the core value of nurses engaged in neonatal nursing is family-oriented nursing. Nurses with 5 or more years of neonatal nursing experience understand patients and their family members well through establishing mutual relationships and providing comfort and safety while taking care of them.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments: We would like to express our gratitude to the Director of Nursing at Tottori University Hospital and nurses in the Comprehensive Center for Perinatal Medicine (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and Growing Care Unit) Center, Tottori University Hospital who supported us in this study. We are also deeply grateful to Kanetoshi Hattori Ph. D. for his support in the text-mining analysis.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

a Conceptualization of nursing: to find the key element in nursing for nurses by looking back on their experiences in nursing practice.

b Theory on Three-Staged Recognition and their Mutual Commitment: a theory on the development of recognition established by Kazuaki Shoji in 1985. Shoji described three stages of recognition: sensuous, presentative, and conceptual.

c Sensuous recognition: a process of acquiring specific information from actual things. It represents recognized emotions about experience, feeling, sense, and sensitivity.

d Presentative recognition: a process of imagining the appearance of a thing in our mind without looking at it. It represents a metaphor, illustration, sign, figure, proverb, or symbol.

e Conceptual recognition: a process of recognizing the nature of common factors among objects. It represents a general ordered structure of multiple factors and the associations among them that arise out of the recognition process.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mercer RT. Becoming a mother versus maternal role attainment. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2004;36:226-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kameoka T, Funashima N. Exploration of the attributes associated with the excellence in nursing practice; focused on the nurses, who have more than 5 years clinical experience. J Nurs Studies NCNJ. 2015;14:1-10. Japanese with English abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kameoka T, Funashima N. Problems that hospital nurses encounter in the nursing profession and their characteristics. J Nurs Studies NCNJ. 2008;7:18-25. Japanese with English abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tsuji C, Ogasawara C. The Plateau Phenomena and Factors Related to the Development of Nurses Practical Abilities. Journal of Japanese Society of Nursing Research. 2007;30:31-5. Japanese with English abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benner P. From Novice To Expert. AJN The American Journal of Nursing. 1982;82:402-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jinda Y. [Nursing can be changed by visualization of the knowledge! ]. Osaka, Japan: Medicus Shuppan; 2015. p.28-13328-44, 108-33. Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Benner PE, Tanner CA, Chesla CA. Expertise in nursing practice: caring, clinical judgment, and ethics. 2nd ed New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2009. p.1-47. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shouji K. [A theory proving three-stage linked recognition..] Tokyo: kisetusha; 2000. p.13-12813-53, 96-128. Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goodman J. Constructing a practical philosophy of teaching: A study of preservice teachers’ professional perspectives. Teaching and Teacher Education. 1988;4:121-37. DOI: 10.1016/0742-051X(88)90013-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gibbs G, Coffey M. Training to teach in higher education: a research agenda. Teacher Development. 2000;4:31-44. DOI: 10.1080/13664530000200103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Driscoll J, Teh B. The potential of reflective practice to develop individual orthopaedic nurse practitioners and their practice. Journal of Orthopaedic Nursing. 2001;5:95-103. DOI: 10.1054/joon.2001.0150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heath H. Keeping a reflective practicediary: a practical guide. Nurse Education Today. 1998;18:592-8. DOI: 10.1016/S0260-6917(98)80010-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feldman R, Sanger J. The text mining handbook: advanced approaches in analyzing unstructured data. Cambridge (England): Cambridge University Press; 2007. p.1-13. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Japanese Nursing Association (JNA). [Standards, principles, and guidelines for nursing]. Tokyo: Japanese Nursing Association Publishing Company; 2016. p.36-7. Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Spichiger E, Wallhagen MI, Benner P. Nursing as a caring practice from a phenomenological perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2005;19:303-9. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00350.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mayeroff M. On Caring. International Philosophical Quarterly. 1965;5:462-74. DOI: 10.5840/ipq1965539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Benner P. Taking a stand on experiential learning and good practice. Am J Crit Care. 2001;10:60-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]