Abstract

We report the first case of a healthy 23-year-old female who underwent an interventional radiology-guided embolization of a hepatic adenoma, which resulted in a gas forming hepatic liver abscess and septicemia by Clostridium paraputrificum. A retrospective review of Clostridial liver abscesses was performed using a PubMed literature search, and we found 57 clostridial hepatic abscess cases. The two most commonly reported clostridial species are C. perfringens and C. septicum (64.9% and 17.5% respectively). C. perfringens cases carried a mortality of 67.6% with median survival of 11 h, and 70.2% of the C. perfringens cases experienced hemolysis. All C. septicum cases were found to have underlying liver malignancy at the time of the presentation with a mortality of only 30%. The remaining cases were caused by various Clostridium species, and this cohort’s clinical course was significantly milder when compared to the above C. perfringens and C. septicum cohorts.

Keywords: Clostridium, Hemolysis, Liver cell adenoma, Morbidity, Mortality, Pyogenic liver abscess

Core tip: To our best knowledge, this is the first case where a liver abscess grew C. paraputrificum. Although pyogenic liver abscesses caused by Clostridium species are extremely rare, early and accurate diagnosis of clostridial hepatic abscess and timely interventions are paramount, as it carries an extremely high morbidity and mortality. However, depending on the exact causative Clostridium species, the clinical course can vary unexpectedly.

INTRODUCTION

Pyogenic liver abscesses caused by Clostridium species are extremely rare[1], and only 57 cases have been reported in the English medical literature (Table 1). C. perfringens was responsible for more than a half of these reported cases. This species carries an extremely high mortality rate, especially when associated with hemolysis[2-4]. The previously reported 20 C. perfringens cases showed a median age of 65 years at the time of presentation[5]. Advanced age, underlying malignancy, liver cirrhosis, and immunocompromised conditions including dialysis, transplant and diabetes mellitus were identified as risk factors[2,5-8]. Here we present a very unusual case of a healthy 23-year-old female who underwent interventional radiology (IR) embolization for a hepatic adenoma and presented within 24 h with a gas forming hepatic liver abscess and septicemia. Due to the extremely rapid clinical presentation where the embolized tumor was completely replaced by a gas forming abscess within a day, C. perfringens was suspected as the causative organism. Unlike many other fatal C. perfringens hepatic abscess cases, our patient did not have any signs of hemolysis nor experienced any end-organ failure. Future speciation work-up revealed C. paraputrificum. There have been five case reports of septicemia caused by C. paraputrificum[9-13]. However, this is the first case of a gas forming hepatic abscess.

Table 1.

Fifty-seven reported clostridial hepatic abscess cases in the English medical literature

| Case | Author | Year | Age | Sex | Species | Underlying disease | HML | SSE | TTD | PLM | PMI |

| 1 | Fiese[35] | 1950 | 67 | M | C. perfringens | Cholecystitis | No | Yes | - | No | Yes |

| 2 | Kivel et al[36] | 1958 | 68 | F | C. perfringens | DM | Yes | No | 5 d | No | No |

| 3 | Kahn et al[37] | 1972 | 44 | F | C. septicum | Colon cancer | No | Yes | - | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | D’Orsi et al[38] | 1979 | 52 | F | C. septicum | Colon cancer | No | Yes | - | Yes | No |

| 5 | D’Orsi et al[38] | 1979 | 51 | F | C. ramosum | Melanoma | Yes | No | 2 d | Yes | No |

| 6 | D’Orsi et al[38] | 1979 | 29 | M | C. ramosum, C. sporogenes | Peri-ampullaryCa | No | Yes | - | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Mera et al[39] | 1984 | 6 | F | C. perfringens | Fanconi’s anemia | Yes | No | 14 h | No | No |

| 8 | Nachman et al[40] | 1989 | 6 | M | C. bifermentans | Blunt trauma | No | Yes | - | No | No |

| 9 | Yood et al[41] | 1989 | 64 | F | C. perfringens | Systemic vasculitis | No | Yes | - | No | No |

| 10 | Batge et al[42] | 1992 | 61 | M | C. perfringens | Pancreatic cancer, DM | Yes | Yes | - | No | No |

| 11 | Rogstad et al[43] | 1993 | 61 | M | C. perfringens | None | Yes | No | 3 h | No | No |

| 12 | Thel et al[32] | 1994 | 39 | F | C. septicum | Breast Ca, Bone M. txp | No | Yes | - | Yes | No |

| 13 | Gutierrez et al[44] | 1995 | 74 | M | C. perfringens | None | Yes | No | 6 h | No | No |

| 14 | Jones et al[45] | 1996 | 66 | F | C. perfringens | OLT, DM | Yes | No | 10 h | No | No |

| 15 | Lee et al[34] | 1999 | 33 | F | C. septicum | Uterine cancer | No | Yes | - | Yes | No |

| 16 | Eckel et al[46] | 2000 | 65 | F | C. perfringens | Cholangiocarcinoma | Yes | Yes | - | Yes | Yes |

| 17 | Urban et al[47] | 2000 | 68 | M | C. septicum | Colon cancer | No | Yes | - | Yes | No |

| 18 | Sakurai et al[48] | 2001 | 75 | F | C. difficile | Hepatic cyst | No | Yes | - | Yes | No |

| 19 | Kreidl et al[8] | 2002 | 80 | M | C. perfringens | DM, dialysis | Yes | No | 11 h | No | No |

| 20 | Sarmiento et al[49] | 2002 | 57 | M | C. septicum | Colon cancer | No | Yes | - | Yes | No |

| 21 | Hsieh et al[50] | 2003 | 23 | M | Unusual C. spp. | Blunt trauma | No | Yes | - | No | No |

| 22 | Quigley et al[51] | 2003 | 73 | M | C. perfringens | Hepatic cyst | - | No | 0 h | Yes | Yes |

| 23 | Elsayed et al[52] | 2004 | 27 | M | C. hathewayi | Cholecystitis | No | Yes | - | No | No |

| 24 | Fondran et al[53] | 2005 | 63 | M | C. perfringens | Pancreatic cancer | No | Yes | - | Yes | Yes |

| 25 | Au et al[7] | 2005 | 65 | M | C. perfringens | DM, dialysis | Yes | No | 3 h | No | No |

| 26 | Kurtz et al[54] | 2005 | 50 | F | C. septicum | Colon cancer | No | Yes | - | Yes | No |

| 27 | Ohtani et al[55] | 2006 | 78 | M | C. perfringens | DM | Yes | No | 3 h | No | No |

| 28 | Daly et al[56] | 2006 | 80 | M | C. perfringens | DM | Yes | No | 3 h | No | No |

| 29 | Loran et al[57] | 2006 | 69 | F | C. perfringens | None | Yes | No | 6 h | No | No |

| 30 | Chiang et al[58] | 2007 | 46 | F | C. perfringens | Cholecystitis | No | No | 7 d | No | No |

| 31 | Abdel-Haq et al[59] | 2007 | 11 | M | C. novyi type B | Blunt trauma | No | Yes | - | No | No |

| 32 | Umgelter et al[60] | 2007 | 87 | F | C. perfringens | Colon cancer | No | Yes | - | Yes | No |

| 33 | Tabarelli et al[61] | 2009 | 65 | F | C. perfringens | Pancr. Ca s/p whipple | No | No | 27 d | No | Yes |

| 34 | Merino et al[62] | 2009 | 83 | F | C. perfringens | None | Yes | No | 3 d | No | No |

| 35 | Saleh et al[63] | 2009 | 53 | M | C. septicum | Colon cancer | No | Yes | - | Yes | No |

| 36 | Meyns et al[64] | 2009 | 64 | M | C. perfringens | DM | Yes | No | 2 d | No | No |

| 37 | Ng et al[4] | 2010 | 61 | F | C. perfringens | DM | Yes | Yes | - | No | Yes |

| 38 | Rajendran et al[65] | 2010 | 58 | M | C. perfringens | None | Yes | Yes | - | No | No |

| 39 | Bradly et al[66] | 2010 | 52 | M | C. perfringens | OLT | Yes | No | 6 h | No | No |

| 40 | Ogah et al[67] | 2012 | 6 | F | C. clostridioforme | None | No | Yes | - | No | No |

| 41 | Qandeel et al[68] | 2012 | 59 | M | C. perfringens | DM, s/p elective chole | Yes | Yes | - | No | No |

| 42 | Kim et al[69] | 2012 | 80 | F | C. perfringens | Hilar cholangiocarcinoma | No | No | 3 d | No | Yes |

| 43 | Huang et al[70] | 2012 | 54 | M | C. baratii | Cholecystitis | No | Yes | - | No | No |

| 44 | Sucandy et al[71] | 2012 | 65 | M | C. septicum | Colon cancer | No | No | 2 d | Yes | No |

| 45 | Law et al[5] | 2012 | 50 | F | C. perfringens | Rectal cancer | Yes | No | 7 d | Yes | No |

| 46 | Raghavendra et al[72] | 2013 | 63 | M | C. septicum | Colon cancer | No | Yes | - | Yes | No |

| 47 | Kitterer et al[73] | 2014 | 71 | M | C. perfringens | OLT, Gastroenteritis | Yes | No | 13 h | No | No |

| 48 | Imai et al[74] | 2014 | 76 | M | C. perfringens | None | Yes | No | 6.5 h | No | No |

| 49 | Kurasawa et al[2] | 2014 | 65 | M | C. perfringens | DM | Yes | No | 6 h | No | No |

| 50 | Eltawansy et al[75] | 2015 | 81 | F | C. perfringens | DM, Gastroenteritis | No | No | N/A1 | No | Yes |

| 51 | Li et al[76] | 2015 | 71 | M | C. perfringens | HCC, Hepatitis B | Yes | Yes | - | Yes | No |

| 52 | Rives et al[77] | 2015 | 63 | M | C. perfringens | Colon cancer | No | Yes | - | Yes | No |

| 53 | Lim et al[6] | 2016 | 58 | M | C. perfringens | None | Yes | No | 7.5 h | No | No |

| 54 | Hashiba et al[78] | 2016 | 82 | M | C. perfringens | DM | Yes | No | 2 h | No | No |

| 55 | Kyang et al[79] | 2016 | 84 | M | C. perfringens | Gastric adenoCA | No | Yes | - | Yes | Yes |

| 56 | Ulger et al[80] | 2016 | 80 | F | C. difficile | DM | No | No | 18 d | No | No |

| 57 | García et al[81] | 2016 | 65 | M | C. perfringens | DM | Yes | Yes | - | No | Yes |

Exact time of TTD was not discussed, but terminal vent weaning was initiated and subsequently expired. HML: Hemolysis; SSE: Survival of septic episode; TTD: Time to death; PLM: Presence of liver mass; PMI: Polymicrobial infection.

CASE REPORT

A 23-year-old healthy female with obesity (body mass index of 37 kg/m2) and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome on oral contraceptive pills was evaluated for intermittent, right upper quadrant abdominal pain. She was found to have a hepatic adenoma measuring 5.2 cm × 3.3 cm × 6.6 cm abutting the liver capsule in segment 7 (Figure 1) on imaging. The patient’s oral contraceptive pill was discontinued for the more than three months, since the adenoma was diagnosed. A repeat computerized tomography (CT) scan did not show regression of the mass (Figure 2). Due to ongoing intractable abdominal right upper quadrant pain and risk of potential rupture, a surgical resection was presented as an option vs IR-guided embolization as an alternative option given her body habitus and fatty liver on magnetic resonance imaging study. The patient elected to proceed with IR embolization.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the segment 7 hepatic adenoma measuring 5.2 cm × 3.3 cm × 6.6 cm.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography after stopping oral contraceptive pills for 3 mo. No change in size.

Angiogram showed conventional hepatic artery anatomy, and the adenoma was exclusively fed by a single branch coming off of the posterior right hepatic artery (Figure 3). The tumor was completely embolized with 100-300 μm trisacryl gelatin microspheres (Embosphere®, Merit Medical Systems, Inc., South Jordan, United States). The patient was discharged home the same day.

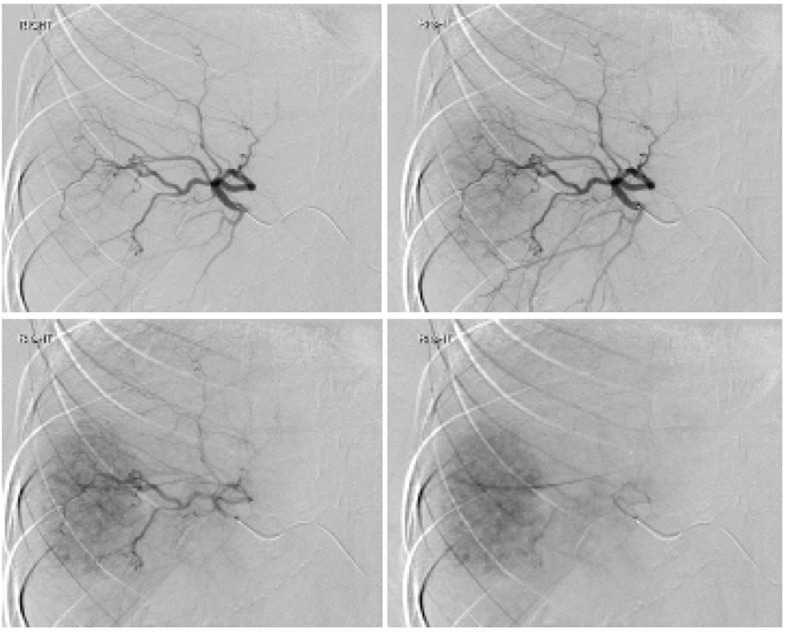

Figure 3.

Interventional radiology angiogram of the hepatic adenoma.

The next day, the patient began to experience a rapid onset of right upper abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and fever of 101.5 °F. In the emergency room, the patient was tachycardic with a heart rate in the 120 s. She experienced right upper abdominal tenderness on physical exam. Blood tests showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 16.4 Thou/μL, a lactic acid of 2.4 nmol/L, a serum aspartate transaminase (AST) of 671 U/L, a serum alanine transaminase (ALT) of 310 U/L, and a total bilirubin (T. bili) of 1.4 mg/dL. A CT scan showed the embolized tumor in segment 7 completely replaced with multiple gas pockets (Figure 4). A set of blood cultures was sent, and the patient was started on vancomycin, levofloxacin and metronidazole (patient has a penicillin allergy). The next day, the set of blood cultures grew gram positive rods. The patient’s serum WBC was elevated to 25 Thou/μL. Later that day, the preliminary blood culture revealed clostridium species. With ongoing fever and the newly diagnosed clostridium species infection, a repeat CT scan was performed to rule out potential life threatening gas gangrene. The repeat CT scan showed no changes.

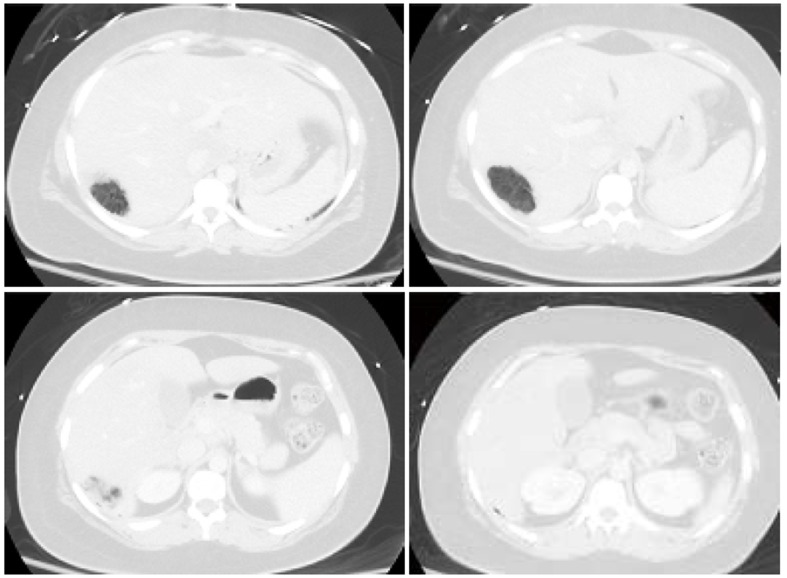

Figure 4.

The tumor completely replaced by gas pockets.

The patient remained persistently febrile, despite antibiotic therapy and subsequent blood cultures showing no growth. The culture speciation showed Clostridium paraputrificum and no other organisms were isolated. Despite improving leukocytosis, an IR-guided drain was placed on hospital day 10 due to the persistent fevers. One hundred and twenty cc of dark turbid sterile fluid was aspirated, and the gram stain showed many neutrophils. No bacteria were isolated. Aspirin was started because the patient’s platelet count rose above 500 Thou/μL. Over the next a few days since the drain placement, the fluid character became less turbid. However, the color became frankly bilious. The daily drain output persistently remained less than 200 cc, indicating a low output bile leak. Thus an ERCP was not performed. On Hospital day 16, the patient was afebrile for the first time. The patient was discharged home on hospital day 17 since the patient was afebrile for 48 hours. At the time of discharge, the drain output was less than 100 cc per day and the patient was discharged on oral metronidazole only.

The patient presented two weeks after discharge with a follow-up CT, which revealed a significantly reduced gas filled abscess cavity (Figure 5). The IR drain was taken out as the daily output remained minimum, less than 5 cc per day. Oral metronidazole was continued for two more weeks post drain removal. Upon completion of the antibiotic course, blood tests showed a WBC of 9.5 Thou/μL, a platelet count of 379 Thou/μL, an AST of 27 U/L, an ALT of 30 U/L, and a T. bili of 0.6 mg/dL.

Figure 5.

Follow-up computed tomography. The gas pocket reduced.

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic liver abscess (PLA) is an uncommon disease. Various incidences have been reported throughout the world: 1.1 in Denmark[14], 2.3 in Canada[15] and 17.6 per 100000 population in Taiwan[16]. In the United States, the incidence is 3.6 per 100000 population with a reported in-hospital mortality rate of 5.6%[17].

The incidences of gas forming pyogenic liver abscess (GFPLA), also known as emphysematous liver abscess, are even rarer, contributing 6.6% to 32% of PLA[16,18-21]. It carries a significantly higher mortality rate, 27.7% to 37.1%[22-25]. For those who presented with GFPLA, their incidence of septic shock was higher (32.5% vs 11.7%) and they presented with a shorter duration of symptoms (5.2 d vs 7.6 d) when compared to those who presented with non-gas forming pyogenic liver abscess (NGFPLA)[22].

The single strongest risk factor for GFPLA appears to be the presence of diabetes and poorly controlled blood glucose[15,18,22]. According to a case report series done in Taiwan which compared 83 patients with GFPLA against 341 NGFPLA patients, 85.5% of those with GFPLA had diabetes mellitus with an initial glucose level of 383.0 ± 167.7 (mg/dL) vs 33.1% with an initial glucose level of 262.6 ± 158.0 (mg/dL)[22]. Similar findings were reported from another single center series from South Korea, where 76% (19 out of 25) were found to have diabetes when comparing 25 patients with GFPLA against 354 NGFPLA patients[18]. The most common causative organism for GFPLA was Klebsiella pneumoniae contributing 77% to 88%[18,22,25]. Escherichia, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, Morganella, Enterobacter, Serratia, Bacteroides and Clostridium species were responsible for the remaining[22].

An extremely small portion of GFPLA is caused by clostridial species. The two most commonly reported clostridium species are C. perfringens and C. septicum. We performed a PubMed literature search and identified 57 clostridium hepatic abscess cases reported in the English medical literature (Table 1). Our search showed that C. perfringens was responsible for 37 cases (64.9%) and C. septicum was responsible for 10 cases (17.5%). Nine cases were caused by C. difficile, C. ramosum, C. sporogenes, C. baratii, C. bifermentans, C. clostridioforme, C. hathewayi, and C. novyi type B. In one case, the exact speciation was not provided due to the institution’s microbiology limitation for identifying rare clostridial species.

C. perfringens septicemia has been reported to carry a mortality rate ranging from 70%-100%[4]. Massive intravascular hemolysis is a well-known complication, occurring in 7%-15% of C. perfringens bacteremia cases[26-28]. C. perfringens’s alpha-toxin has been shown be the key virulent factor for this clinical course, by inducing gas gangrene and causing massive hemolysis by destroying red cell membrane integrity[3]. In our 37 cases of C. perfringens hepatic abscess, the mortality rate was 67.6% (25/37). 70.2% (26/37) experienced hemolysis (Table 1). Among the 25 patients who died, one patient died prior to arriving to the hospital. The mean time of survival for these 24 patients was 11 h. Among the 25 patients who died, only 4 patients (16%) were found to have poly-microbial infection, whereas among those who survived, 6 patients (50%) were found to have poly-microbial infection. The most common underlying disease was diabetes (11/37) followed by underlying malignancy (10/37). Interestingly, 7 patients were found to have no clear underlying medical disease.

Among the 10 cases of C. septicum species (Table 1), the patient survival was greater, 70% (7/10). Furthermore, no hemolysis was reported in contrast to the C. perfringens cases. Of note, C. septicum also produces alpha toxin, but it was shown to be unrelated to the alpha toxin of C. perfringens[29]. C. septicum infection has been well known to be associated with underlying occult malignancy[30-33]. It has been hypothesized that a rapidly growing tumor with anaerobic glycolysis provides a relatively hypoxic and acidic environment for germination of the clostridial spores[34]. In fact, all of the ten patients had infected liver tumors at the time of the presentation, and only one patient (10%) was found to have a poly-microbial infection.

The remaining 10 cases where the infection was caused by various clostridial species, including the one with no provided speciation, appeared to have a milder clinical course when compared to the above C. perfringens and C. septicum cohorts (Table 1). The mortality rate was lower, only 20%, and median age at the time of presentation was significantly younger, 27 years. Interestingly, trauma was the underlying disease for the three cases.

Here, we report a young, healthy 23-year-old female who was diagnosed with a hepatic abscess caused by Clostridium paraputrificum. Due to the extremely rapid clinical presentation and from the initial imaging study where the mass was completely replaced with multiple gas pockets, a C. perfringens infection was highly suspected. Unlike many typical C. perfringens hepatic abscess cases, our patient did not experience hemolysis nor had any end organ failure requiring ICU care. In addition, our patient did not have the typical risk factors for C. perfringens nor C. septicum infections, except for having a tumor in the liver. At the end, the causative organism was identified as Clostridium paraputrificum, which has not been reported before in the literature. A Clostridium hepatic abscess is an extremely rare case and C. perfringens is the most common causative organism. Early accurate diagnosis and timely interventions are paramount, as it carries an extremely high mortality. However, depending on the exact causative clostridial species, the clinical course can vary significantly.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Case characteristics

A healthy 23-year-old female developed a Clostridium paraputrificum gas forming liver abscess within 24 h after interventional radiology hepatic adenoma embolization.

Clinical diagnosis

The patient’s source of sepsis was unequivocally identified once an imaging study showed a gas forming liver abscess.

Differential diagnosis

Klebsiella pneumonia was suspected to be the causative organism initially as it is known to contributing 77% to 88% of all gas forming pyogenic liver abscesses.

Laboratory diagnosis

In addition to severe leukocytosis and lactic acidosis, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, deceased haptoglobin and elevated bilirubin, signs of massive hemolysis, can be also seen in certain patients.

Imaging diagnosis

A gas forming liver abscess can be diagnosed with an abdominal X-ray or ultrasound, but typically a computed tomography scan is commonly used for the diagnosis.

Pathological diagnosis

A needle aspiration of the hepatic abscess and/or blood culture often will yield the causative organism.

Treatment

An early recognition and treatment with antibiotics is paramount as Clostridium hepatic abscess infections are often extremely aggressive and lethal.

Related reports

There have been five case reports of septicemia caused by C. paraputrificum, however, none of them caused hepatic abscess.

Term explanation

Pyogenic liver abscess (PLA) is an uncommon disease. The incidences of gas forming pyogenic liver abscess (GFPLA) also known as emphysematous liver abscess, are even rarer, contributing 6.6% to 32% of PLA.

Experiences and lessons

A Clostridium hepatic abscess requires early accurate diagnosis and timely interventions, as it carries an extremely high mortality. However, depending on the exact causative clostridial species, the clinical course can vary significantly.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent and permission to write this manuscript was obtained from the patient of this case report.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors certify that we have no conflict of interest to disclose and did not receive any financial support for this study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: December 20, 2017

First decision: January 23, 2018

Article in press: March 1, 2018

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Cerwenka H, Stanciu C S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

Contributor Information

Yong K Kwon, Department of Transplant, Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT 06106, United States. yong.kwon@hhchealth.org.

Faiqa A Cheema, Department of Transplant, Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT 06106, United States.

Bejon T Maneckshana, Department of Transplant, Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT 06106, United States.

Caroline Rochon, Department of Transplant, Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT 06106, United States.

Patricia A Sheiner, Department of Transplant, Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT 06106, United States.

References

- 1.Khan MS, Ishaq MK, Jones KR. Gas-Forming Pyogenic Liver Abscess with Septic Shock. Case Rep Crit Care. 2015;2015:632873. doi: 10.1155/2015/632873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurasawa M, Nishikido T, Koike J, Tominaga S, Tamemoto H. Gas-forming liver abscess associated with rapid hemolysis in a diabetic patient. World J Diabetes. 2014;5:224–229. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i2.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Bunderen CC, Bomers MK, Wesdorp E, Peerbooms P, Veenstra J. Clostridium perfringens septicaemia with massive intravascular haemolysis: a case report and review of the literature. Neth J Med. 2010;68:343–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng H, Lam SM, Shum HP, Yan WW. Clostridium perfringens liver abscess with massive haemolysis. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:310–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Law ST, Lee MK. A middle-aged lady with a pyogenic liver abscess caused by Clostridium perfringens. World J Hepatol. 2012;4:252–255. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v4.i8.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim AG, Rudd KE, Halliday M, Hess JR. Hepatic abscess-associated Clostridial bacteraemia presenting with intravascular haemolysis and severe hypertension. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:pii: bcr2015213253. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-213253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Au WY, Lau LS. Massive haemolysis because of Clostridium perfringens [corrected] liver abscess in a patient on peritoneal dialysis. Br J Haematol. 2005;131:2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreidl KO, Green GR, Wren SM. Intravascular hemolysis from a Clostridium perfringens liver abscess. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:387. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nerad JL, Pulvirenti JJ. Clostridium paraputrificum bacteremia in a patient with AIDS and Duodenal Kaposi’s sarcoma. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1183–1184. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.5.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brook I. Clostridial Infections in Children: Spectrum and Management. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2015;17:47. doi: 10.1007/s11908-015-0503-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shandera WX, Humphrey RL, Stratton LB. Necrotizing enterocolitis associated with Clostridium paraputrificum septicemia. South Med J. 1988;81:283–284. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198802000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nachamkin I, DeBlois GE, Dalton HP. Clostridium paraputrificum bacteremia associated with aspiration pneumonia. South Med J. 1982;75:1023–1024. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198208000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Babenco GO, Joffe N, Tischler AS, Kasdon E. Gas-forming clostridial mycotic aneurysm of the abdominal aorta. A case report. Angiology. 1976;27:602–609. doi: 10.1177/000331977602701007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen PS, Schønheyder HC. Pyogenic hepatic abscess. A 10-year population-based retrospective study. APMIS. 1998;106:396–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1998.tb01363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan GG, Gregson DB, Laupland KB. Population-based study of the epidemiology of and the risk factors for pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1032–1038. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai FC, Huang YT, Chang LY, Wang JT. Pyogenic liver abscess as endemic disease, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1592–1600. doi: 10.3201/eid1410.071254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meddings L, Myers RP, Hubbard J, Shaheen AA, Laupland KB, Dixon E, Coffin C, Kaplan GG. A population-based study of pyogenic liver abscesses in the United States: incidence, mortality, and temporal trends. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:117–124. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee CJ, Han SY, Lee SW, Baek YH, Choi SR, Roh MH, Lee JH, Jang JS, Han J, Cho SH, et al. Clinical features of gas-forming liver abscesses: comparison between diabetic and nondiabetic patients. Korean J Hepatol. 2010;16:131–138. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2010.16.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitt HA. Surgical management of hepatic abscesses. World J Surg. 1990;14:498–504. doi: 10.1007/BF01658675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halvorsen RA Jr, Foster WL Jr, Wilkinson RH Jr, Silverman PM, Thompson WM. Hepatic abscess: sensitivity of imaging tests and clinical findings. Gastrointest Radiol. 1988;13:135–141. doi: 10.1007/BF01889042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubinson HA, Isikoff MB, Hill MC. Diagnostic imaging of hepatic abscesses: a retrospective analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980;135:735–745. doi: 10.2214/ajr.135.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou FF, Sheen-Chen SM, Chen YS, Lee TY. The comparison of clinical course and results of treatment between gas-forming and non-gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess. Arch Surg. 1995;130:401–405; discussion 406. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430040063012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee TY, Wan YL, Tsai CC. Gas-containing liver abscess: radiological findings and clinical significance. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:47–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02165861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang CC, Chen CY, Lin XZ, Chang TT, Shin JS, Lin CY. Pyogenic liver abscess in Taiwan: emphasis on gas-forming liver abscess in diabetics. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1911–1915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee HL, Lee HC, Guo HR, Ko WC, Chen KW. Clinical significance and mechanism of gas formation of pyogenic liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2783–2785. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2783-2785.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caya JG, Truant AL. Clostridial bacteremia in the non-infant pediatric population: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:291–298. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199903000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rechner PM, Agger WA, Mruz K, Cogbill TH. Clinical features of clostridial bacteremia: a review from a rural area. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:349–353. doi: 10.1086/321883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bodey GP, Rodriguez S, Fainstein V, Elting LS. Clostridial bacteremia in cancer patients. A 12-year experience. Cancer. 1991;67:1928–1942. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910401)67:7<1928::aid-cncr2820670718>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ballard J, Bryant A, Stevens D, Tweten RK. Purification and characterization of the lethal toxin (alpha-toxin) of Clostridium septicum. Infect Immun. 1992;60:784–790. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.784-790.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kornbluth AA, Danzig JB, Bernstein LH. Clostridium septicum infection and associated malignancy. Report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1989;68:30–37. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolbeinsson ME, Holder WD Jr, Aziz S. Recognition, management, and prevention of Clostridium septicum abscess in immunosuppressed patients. Arch Surg. 1991;126:642–645. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410290120024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thel MC, Ciaccia D, Vredenburgh JJ, Peters W, Corey GR. Clostridium septicum abscess in hepatic metastases: successful medical management. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1994;13:495–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirchner JT. Clostridium septicum infection. Beware of associated cancer. Postgrad Med. 1991;90:157–160. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1991.11701080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee CH, Hsieh SY. Case report: Clostridium septicum infection presenting as liver abscess in a case of choriocarcinoma with liver metastasis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:1227–1229. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiese MJ. Tympany over the liver in hepatic abscess caused by Clostridium welchii. Report of a case. Calif Med. 1950;73:505–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kivel RM, Kessler A, Cameron DJ. Liver abscess due to Clostridium perfringens. Ann Intern Med. 1958;49:672–679. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-49-3-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kahn SP, Lindenauer SM, Wojtalik RS, Hildreth D. Clostridia hepatic abscess. An unusual manifestation of metastatic colon carcinoma. Arch Surg. 1972;104:209–212. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1972.04180020089018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D’Orsi CJ, Ensminger W, Smith EH, Lew M. Gas-forming intrahepatic abscess: a possible complication of arterial infusion chemotherapy. Gastrointest Radiol. 1979;4:157–161. doi: 10.1007/BF01887516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mera CL, Freedman MH. Clostridium liver abscess and massive hemolysis. Unique demise in Fanconi’s aplastic anemia. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1984;23:126–127. doi: 10.1177/000992288402300215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nachman S, Kaul A, Li KI, Slim MS, San Filippo JA, Van Horn K. Liver abscess caused by Clostridium bifermentans following blunt abdominal trauma. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1137–1138. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.5.1137-1138.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 42-1989. A 64-year-old woman with a liver abscess, Clostridium perfringens sepsis, progressive sensorimotor neuropathy, and abnormal serum proteins. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1103–1118. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198910193211608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bätge B, Filejski W, Kurowski V, Klüter H, Djonlagic H. Clostridial sepsis with massive intravascular hemolysis: rapid diagnosis and successful treatment. Intensive Care Med. 1992;18:488–490. doi: 10.1007/BF01708587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogstad B, Ritland S, Lunde S, Hagen AG. Clostridium perfringens septicemia with massive hemolysis. Infection. 1993;21:54–56. doi: 10.1007/BF01739316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gutiérrez A, Florencio R, Ezpeleta C, Cisterna R, Martínez M. Fatal intravascular hemolysis in a patient with Clostridium perfringens septicemia. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1064–1065. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.4.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones TK, O’Sullivan DA, Smilack JD. 66-year-old woman with fever and hemolysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:1007–1010. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(11)63777-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eckel F, Lersch C, Huber W, Weiss W, Berger H, Schulte-Frohlinde E. Multimicrobial sepsis including Clostridium perfringens after chemoembolization of a single liver metastasis from common bile duct cancer. Digestion. 2000;62:208–212. doi: 10.1159/000007815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urban BA, McCormick R, Fishman EK, Lillemoe KD, Petty BG. Fulminant Clostridium septicum infection of hepatic metastases presenting as pneumoperitoneum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:962–964. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.4.1740962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakurai T, Hajiro K, Takakuwa H, Nishi A, Aihara M, Chiba T. Liver abscess caused by Clostridium difficile. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001;33:69–70. doi: 10.1080/003655401750064112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarmiento JM, Sarr MG. Necrotic infected liver metastasis from colon cancer. Surgery. 2002;132:110–111. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.118262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hsieh CH, Hsu YP. Early-onset liver abscess after blunt liver trauma: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:392–394. doi: 10.1007/s005950300089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quigley M, Joglekar VM, Keating J, Jagath S. Fatal Clostridium perfringens infection of a liver cyst. J Infect. 2003;47:248–250. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(03)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elsayed S, Zhang K. Human infection caused by Clostridium hathewayi. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1950–1952. doi: 10.3201/eid1011.040006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fondran J, Williams GB. Liver metastasis presenting as pneumoperitoneum. South Med J. 2005;98:248–249. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000153196.84534.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kurtz JE, Claudel L, Collard O, Limacher JM, Bergerat JP, Dufour P. Liver abscess due to clostridium septicum. A case report and review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:1557–1558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohtani S, Watanabe N, Kawata M, Harada K, Himei M, Murakami K. Massive intravascular hemolysis in a patient infected by a Clostridium perfringens. Acta Med Okayama. 2006;60:357–360. doi: 10.18926/AMO/30725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daly JJ, Haeusler MN, Hogan CJ, Wood EM. Massive intravascular haemolysis with T-activation and disseminated intravascular coagulation due to clostridial sepsis. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loran MJ, McErlean M, Wilner G. Massive hemolysis associated with Clostridium perfringens sepsis. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:881–883. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chiang KH, Chou AS, Chang PY, Huang HW. Gas-containing liver abscess after transhepatic percutaneous cholecystostomy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:940–941. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abdel-Haq NM, Chearskul P, Salimnia H, Asmar BI. Clostridial liver abscess following blunt abdominal trauma: case report and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39:734–737. doi: 10.1080/00365540701199865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Umgelter A, Wagner K, Gaa J, Stock K, Huber W, Reindl W. Pneumobilia caused by a clostridial liver abscess: rapid diagnosis by bedside sonography in the intensive care unit. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1267–1269. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.9.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tabarelli W, Bonatti H, Cejna M, Hartmann G, Stelzmueller I, Wenzl E. Clostridium perfringens liver abscess after pancreatic resection. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2009;10:159–162. doi: 10.1089/sur.2008.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Merino A, Pereira A, Castro P. Massive intravascular haemolysis during Clostridium perfrigens sepsis of hepatic origin. Eur J Haematol. 2010;84:278–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saleh N, Sohail MR, Hashmey RH, Al Kaabi M. Clostridium septicum infection of hepatic metastases following alcohol injection: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:9408. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-9408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meyns E, Vermeersch N, Ilsen B, Hoste W, Delooz H, Hubloue I. Spontaneous intrahepatic gas gangrene and fatal septic shock. Acta Chir Belg. 2009;109:400–404. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2009.11680447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rajendran G, Bothma P, Brodbeck A. Intravascular haemolysis and septicaemia due to Clostridium perfringens liver abscess. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010;38:942–945. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1003800522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bradly DP, Collier M, Frankel J, Jakate S. Acute Necrotizing Cholangiohepatitis With Clostridium perfringens: A Rare Cause of Post-Transplantation Mortality. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2010;6:241–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ogah K, Sethi K, Karthik V. Clostridium clostridioforme liver abscess complicated by portal vein thrombosis in childhood. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:297–299. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.031765-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qandeel H, Abudeeb H, Hammad A, Ray C, Sajid M, Mahmud S. Clostridium perfringens sepsis and liver abscess following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Surg Case Rep. 2012;2012:5. doi: 10.1093/jscr/2012.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim JH, Jung ES, Jeong SH, Kim JS, Ku YS, Hahm KB, Kim JH, Kim YS. A case of emphysematous hepatitis with spontaneous pneumoperitoneum in a patient with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Korean J Hepatol. 2012;18:94–97. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2012.18.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang WC, Lee WS, Chang T, Ou TY, Lam C. Emphysematous cholecystitis complicating liver abscess due to Clostridium baratii infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012;45:390–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sucandy I, Gallagher S, Josloff RK, Nussbaum ML. Severe clostridium infection of liver metastases presenting as pneumoperitoneum. Am Surg. 2012;78:E338–E339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Raghavendra GK, Carr M, Dharmadhikari R. Colorectal cancer liver metastasis presenting as pneumoperitoneum: case report and literature review. Indian J Surg. 2013;75:266–268. doi: 10.1007/s12262-012-0666-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kitterer D, Braun N, Jehs MC, Schulte B, Alscher MD, Latus J. Gas gangrene caused by clostridium perfringens involving the liver, spleen, and heart in a man 20 years after an orthotopic liver transplant: a case report. Exp Clin Transplant. 2014;12:165–168. doi: 10.6002/ect.2013.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Imai J, Ichikawa H, Tobita K, Watanabe N. Liver abscess caused by Clostridium perfringens. Intern Med. 2014;53:917–918. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eltawansy SA, Merchant C, Atluri P, Dwivedi S. Multi-organ failure secondary to a Clostridium perfringens gaseous liver abscess following a self-limited episode of acute gastroenteritis. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:182–186. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.893046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li JH, Yao RR, Shen HJ, Zhang L, Xie XY, Chen RX, Wang YH, Ren ZG. Clostridium perfringens infection after transarterial chemoembolization for large hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4397–4401. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rives C, Chaudhari D, Swenson J, Reddy C, Young M. Clostridium perfringens liver abscess complicated by bacteremia. Endoscopy. 2015;47 Suppl 1 UCTN:E457. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1392867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hashiba M, Tomino A, Takenaka N, Hattori T, Kano H, Tsuda M, Takeyama N. Clostridium Perfringens Infection in a Febrile Patient with Severe Hemolytic Anemia. Am J Case Rep. 2016;17:219–223. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.895721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kyang LS, Bin Traiki TA, Alzahrani NA, Morris DL. Microwave ablation of liver metastasis complicated by Clostridium perfringens gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess (GPLA) in a patient with past gastrectomy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;27:32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ulger Toprak N, Balkose G, Durak D, Dulundu E, Demirbaş T, Yegen C, Soyletir G. Clostridium difficile: A rare cause of pyogenic liver abscess. Anaerobe. 2016;42:108–110. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.García Carretero R, Romero Brugera M, Vazquez-Gomez O, Rebollo-Aparicio N. Massive haemolysis, gas-forming liver abscess and sepsis due to Clostridium perfringens bacteraemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:pii: bcr2016218014. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-218014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]