Abstract

Background:

A common phenotype associated with heart failure is the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiac hypertrophy occurs in response to stress, such as hypertension, coro-nary vascular disease, or myocardial infarction. The most critical pathophysiological conditions in-volved may include dilated hypertrophy, fibrosis and contractile malfunction. The intricate pathophys-iological mechanisms of cardiac hypertrophy have been the core of several scientific studies, which may help in opening a new avenue in preventive and curative procedures.

Objectives:

To our knowledge from the literature, the development of cardiac remodeling and hyper-trophy is multifactorial. Thus, in this review, we will focus and summarize the potential role of oxida-tive stress in cardiac hypertrophy development.

Conclusion:

Oxidative stress is considered a major stimulant for the signal transduction in cardiac cells pathological conditions, including inflammatory cytokines, and MAP kinase. The understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms which are involved in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling process is crucial for the development of new therapeutic plans, especially that the mortality rates re-lated to cardiac remodeling/dysfunction remain high

Keywords: Reactive oxygen species, mitochondria, remodeling, protein kinase-C, NAPDH, hypertrophy

1. Introduction

The term oxidative stress refers to an imbalance between the production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and the ability of the body to detoxify the reactive intermediates. This overload in reactive species causes oxidative damage to several cellular elements. ROS regulate hemostasis as well as many cellular signaling including long term potentiation (LTP) induction [1], synaptic plasticity [2], and modulators in cognitive performance [3, 4]. Additionally, several studies had shown that excessive production of ROS contributes to the pathogenesis of heart failure [5]. Furthermore, antioxidant treatment has a cardioprotective effect and reduces cardiac remodeling [6].

Under normal physiological conditions, the level of ROS production is meticulously controlled through the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as copper-zinc superoxide dismutase, manganese-superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione reductase and peroxidase [7-9]. ROS production is physiologically important to regulate various signaling pathways, but overproduction and accumulation of free radicals are detrimental for cardiac health. On the other hand, overproduction of oxidized products such as aldehydes, carbonyls and oxidized bases resulting from lipid peroxidation, protein and DNA oxidation, respectively, are considered significant markers of excess oxidative stress [10]. This study will provide a general updated review regarding the role of oxidative stress in cardiac hypertrophy development.

2. Oxidative Stress

Oxidative damage to cellular macromolecules is believed to underlie the development of many pathological states and aging. Generally, reactive oxygen species such as free radicals (superoxide [O2•—], nitric oxide [NO−], hydroxyl [OH−]) and non-radical byproducts of O2 (e.g. hydrogen peroxide [H2O2], peroxynitrites [ONOO−]) are the most studied species and are highly associated with various pathological conditions. Mitochondria are the main organelles responsible for reactive species production [11]. Superoxide is the primary species produced by the mitochondria; most of the generated superoxide is converted to hydrogen peroxide by the action of superoxide dismutase enzyme. The production of superoxide by mitochondria has been localized to several enzymes of the electron transport chain (ETC), including complexes I, III and glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [12, 13]. Conversely, reduction of oxygen (O2) availability initiates adaptive responses in multicellular organisms. For example, the hypoxic stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factors-alpha (HIF-1 α and HIF-2 α) is required by the functionality of complex III of the mitochondrial ETC; therefore, an increase in ROS links this complex to HIF-alpha stabilization [14].

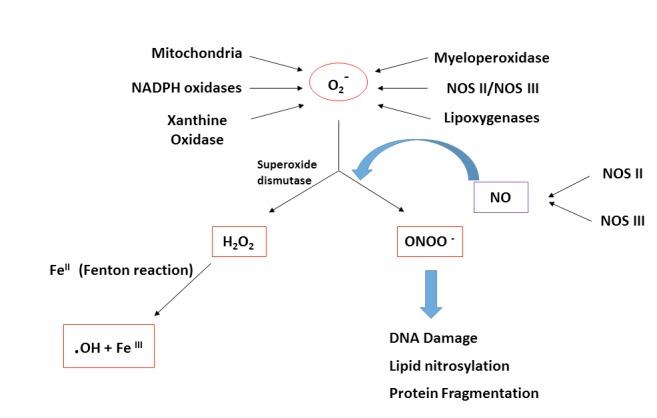

Most superoxides are converted to H2O2 inside and outside the mitochondrial matrix by superoxide dismutase enzymes. H2O2 is a major chemical mediator, which, in low concentrations, affects the physiological functions of different cells. Under pathophysiological conditions, such as hypoxia, cell ischemia or toxin exposure, the amount of O2•— produced will overwhelm both the antioxidant defense mechanisms and ROS scavenger systems (Fig. 1). H2O2 can combine with ferrous (Fe2+) complexes to form reactive ferryl species, which combine with nitric oxide to produce reactant peroxynitrite (Fig. 1). Peroxynitrites cause lipid, DNA and protein nitrosylation which negatively affects cell functions. Therefore, prevention of excessive O2•— production is highly desired [15]. This can be achieved by: (1) cells selectively boosting their antioxidant capacity (2) uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation to reduce generation of O2•— by inducing proton leak, and (3) reversibly inhibiting the electron transport. However, there are many physiologically cell signaling pathways, which can be mediated by ROS such as their effect on thiol and disulfide bridges that affect directly diverse protein structures to stimulate/inhibit phosphatase/kinase signaling pathways [11, 15].

Fig. (1).

The formation of peroxynitrite and hydrogen peroxide. Schematic representation for the formation of peroxynitrite anion (ONOO -) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Superoxide (O2-) will be either converted to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or react with nitric oxide (NO) in order to form the highly reactive intermediate peroxynitrite anion (ONOO-). Peroxynitrite can cause an oxidative damage for molecules in the cells, including DNA and proteins. Abbreviations: O2-: superoxide; NO: nitric oxide; H2O2: hydrogen peroxide; ONOO-: peroxynitrite anion; OH: hydroxyl radical; NOS II/NOS III: nitric oxide synthase.

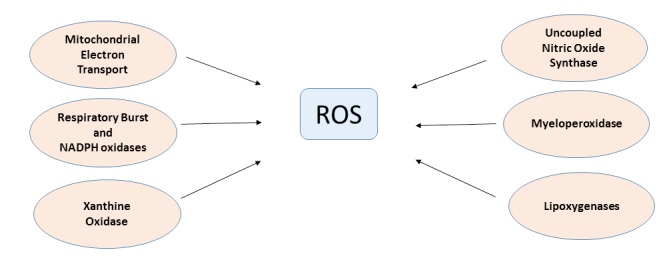

ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) have both deleterious as well as beneficial roles. ROS and RNS are physiologically produced by securely regulated enzymes, such as nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases (NADPH oxidase), respectively (Fig. 2). The favorable effects of ROS/RNS occur at low/moderate levels and participate in many physiological pathways that protect the body against infection. Conversely, the overproduction of ROS may cause detrimental effects, which ultimately end up with cell damage [15, 16]. Thus, the cell tries to reach a “redox homeostasis” or a “redox balance” state.

Fig. (2).

Generation pathways of ROS in the heart. General scheme for Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) endogenous generation pathways in cardiac myocytes. Abbreviations: ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species; NADPH: Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Oxidase.

3. ROS production in cardiovascular disease (CVD)

Increased ROS production has been implicated in the pathophysiology of heart failure and Left Ventricular (LV) hypertrophy. Li, J.M. et al. found that there was a significant increase in the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1/2, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase when they studied the expression and activity of phagocyte-type NADPH oxidase in LV myocardium in an experimental guinea pig model of progressive pressure-overload LV hypertrophy [17]. These data indicate that NADPH oxidase expressed in the cardiomyocyte is a major source of ROS generation in pressure overload LV hypertrophy and may contribute to pathophysiological changes such as the activation of redox-sensitive kinases and progression to heart failure.

Substantial evidence supports the involvement of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of congestive heart failure and precursor conditions such as cardiac hypertrophy and myocardial post-infarction remodeling. These conditions occur when there is an imbalance between antioxidant defense and the production of ROS. NADPH oxidases, a source of ROS (Fig. 2), are especially important in redox signaling, being implicated in the pathophysiology of hypertension and atherosclerosis [18]. In addition to profound alteration of cellular function by increased interstitial and perivascular fibrosis, ROS also activate a broad variety of pro-hypertrophy signaling kinases and transcription factors including MAP kinase and NFκ-B. Translocator Protein (TSPO) present in the outer mitochondrial membrane is known to be involved in oxidative stress and cardiovascular pathology as well [11]. Additionally, the increase in heart rate per second, independent of sympathetic nerve activity, enhances cardiac oxidative stress and activates mitogen-activated protein kinases, which seem to be responsible for cardiac remodeling [19].

Recently, Tigchelaar W. et al. investigated the role of EXOG (exo/endonuclease G) in mitochondrial function and hypertrophy in primary Neonatal Rat Ventricular Cardiomyocytes (NRVCs) cells. A locus at the mitochondrial exo/endonuclease EXOG gene was linked with cardiac function. Diminution of EXOG in NRVCs resulted in a significant increase in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. However, it was shown that the mitochondrial Oxidative Consumption Rate (OCR) was increased 2.4-fold in EXOG- exhausted NRVCs, which was accompanied by a 5.4-fold increase in mitochondrial ROS levels. This upsurge of ROS levels could be controlled with specific mitochondrial ROS defense system (MitoTEMPO [mitochondria-targeted superoxide dismutase], MnSOD [Manganese superoxide dismutase]). Thus, scavenging of additional ROS mitigated the hypertrophic response. In summary, depletion of EXOG-gene affects regular mitochondrial task causing an increased ROS production, and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy development [20].

Hypertension is one of the most important risk factors associated with the development of Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs) [21]. Oxidative stress has been shown to play an important role in the pathophysiology of hypertension. The alteration of the vasomotor system involves ROS as facilitators of vasoconstriction stimulated by some vasoactive peptides such as endothelin-1, angiotensin II and urotensin II [22-24]. Additionally, the bioavailability of the vasodilatory system is extremely dependent on the redox system status [25]. Under normal physiological conditions, moderate intracellular levels of ROS are vital for the redox signaling pathways to preserve vascular parameters. Conversely, during pathophysiological states, elevated concentrations of ROS lead to vascular dysfunction and remodeling via oxidative injury. Interestingly, the use of antioxidants protects against vascular endothelial damage [21, 24]. In general, regarding human hypertension, an increase in the generation of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide, a reduction in NO synthesis, and a decrease in the antioxidant bioavailability has been observed by Rodrigo R. et al. to contribute significantly to the pathogenesis [25].

Oxidative stress plays a critical role in the development of diabetic related cardiovascular complications, such as myocardial hypertrophy. Liu Y. et al. hypothesized that myocardial kinases specifically protein kinase-C isoform-β (PKC-β) is the major upstream moderator of oxidative stress in diabetes and that inhibition of PKC-β can diminish myocardial hypertrophy and cardiac dysfunction. The proposed mechanism is that oxidative stress modulates the PKC-β expression, which is preferentially over-expressed in the diabetic myocardium, with amplified stimulation of the pro-oxidant enzyme NADPH oxidase, that may aggravate oxidative stress [26]. Hence, several risk factors are associated with oxidative stress development and ultimately cardiac diseases. For instance, smoking, lipid abnormalities, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, genetic predisposition and life stressors.

4. Cardiac Hypertrophy and Remodeling

The common phenotype associated with heart failure is the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertrophy is defined as a physiological increase in heart size in order to compensate the increase in cardiac workload. The heart is considered to be a highly adaptable organ that, upon either increase in myocardial reperfusion need or upon loss of cardiac reperfusion, is able to compensate by increasing Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) stimulation and activation of adrenergic receptors in order to increase cardiac output. In the acute setting these adaptive mechanisms may save the heart, however chronic stimulation of the heart along with limited capacity reserve will cause extensive morphological changes and exacerbate cardiac dysfunction.

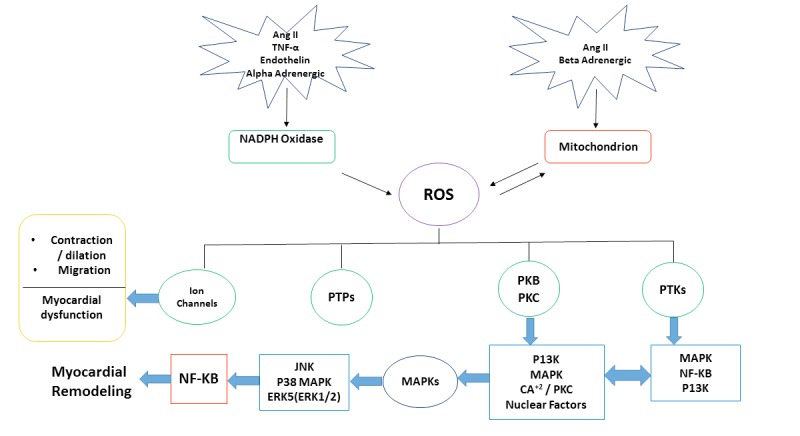

The persistent activation of kinases and phosphatases such as Protein Kinases A, C (PKA, PKC), and calcineurin (PP2B) as a result of chronic beta-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) stimulation leads to the activation of pro-hypertrophic genes (Fig. 3). The activation of these genes triggers cardiac remodeling, which is characterized by changes in the cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle cells, vascular endothelial cells, and inflammatory cells in addition to changes in the size, shape, geometry and function of the heart. For example, decreased PKA-dependent phosphorylation of troponin I, cardiac- myosin binding protein -C and phospholamban in heart failure has been linked to increase ventricular remodeling. Calcineurin dephosphorylates the transcription factor NFATc causing its translocation into the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, NFATc causes the transcription of genes involved in cardiac remodeling and hypertrophy [27-29].

Fig. (3).

ROS and cardiac hypertrophy molecular signaling pathways. General diagram represents the cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling process to ROS - activated molecular signaling pathways in cardiac myocytes .Pathways include non-receptor protein kinases (PTKs), protein phosphatases (PTPs), Mitogen-activated Protein Kinases (MAPKS) and Nuclear Factor kB (NF-KB). Abbreviations: PTKs: Non-Receptor Protein Kinases; PKB: Protein Kinase B; PKC: Protein Kinase C; PTPs: Protein Phosphatases; MAPKS: Mitogen- Activated Protein Kinases; NF-KB: Nuclear Factor KB; P13K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; ERK: Extracellular Signal- Regulated Kinases; Ang II: Angiotensin II; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha; JNK: Jun Nuclear Kinase.

Although the complete picture of the cardiac remodeling process is still unclear, the following scenario has been suggested. When the myocytes stretch, the release of angiotensin, norepinephrine and endothelin will increase [30]. Accordingly, these changes will stimulate the expression of altered proteins and myocyte hypertrophy. The final step of this process will be in the form of further deterioration in cardiac performance and a continuous increase in the neurohormonal activation [31]. Additionally, the increased activation of cytokines and aldosterone will play a role in the stimulation of collagen synthesis, which will lead to fibrosis and remodeling of the extracellular matrix [32].

Several studies have revealed the implications that could arise from overstimulation of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) through contributing to a chain of events, which play a role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease (Fig. 3), including the development of cardiac remodeling [33]. The underlying mechanism of the cardiovascular pathogenesis has been associated with actions of angiotensin II (Ang II). The activation of the Ang II type 1 (AT1) receptor will stimulate vascular remodeling, leading to an elevation in the blood pressure as well as participation in the chronic disease pathology by activating cardiac fibroblasts, stimulation of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, promotion of endothelial dysfunction and increased collagen deposition [34]. Some studies have suggested the association between the RAS system and cardiac damage through the role of Ang II as a modulator of immune mechanisms in hypertension [35]. Ang II is involved in every step of the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease starting from atherosclerosis till cardiac remodeling and end-stage heart failure [36, 37].

A-Kinase Anchoring Proteins (AKAPs) are a diverse group of scaffolding proteins that shape multi-protein complexes and combine cAMP signaling with different effector proteins such as protein kinases [38]. Many AKAPs have been identified in the heart, where they play a significant role in regulating the cardiac remodeling process in three main areas. The first one is the involvement of AKAPs in the modulation of excitation-contraction coupling through regulation of calcium homeostasis, including isoforms of AKAP15/18 (which target PKA to the L-type Ca2+) and muscle – specific A-kinase anchoring protein (mAKAP which targets PKA in the proximity of the RyR2) [29]. Additionally, AKAPs play major a signaling role in the sarcomeric regulation process and the induction of pathological hypertrophy. Despite this role of AKAPs, it is still not fully understood how AKAPs signaling complexes are altered and changed during the progression of heart disease and how this could affect the process of cardiac remodeling [39].

The miRNAs (MicroRNAs) are a short noncoding RNAs that function in regulating gene expressions post-transcriptionally [40]. They usually initiate silencing by binding to special target sites (untranslated region) found within the 3’UTR of the targeted mRNA. Many studies had shown some dysregulated miRNA expression in many animal models of cardiac hypertrophy induced by one of the following mechanisms: activating calcineurin signaling or thoracic-aortic banding [41]. The analysis of such dysregulated miRNA expression has shown that miRNAs may have regulatory effects on cardiac hypertrophic pathways either in a positive or negative way. For example, some studies elucidated the role of miR-1 in cardiac hypertrophy by proposing the inverse relationship between its expression and the progression of cardiac hypertrophy [42]. Other studies discussed the role of miR-133 in regulating cardiac hypertrophy by demonstrating its role in the induction of cardiac hypertrophy [43, 44].

The multifunctional Ca2+/Calmodulin Dependent Protein Kinase (CaMKII) plays a significant and central role in the contractility and structure of the cardiomyocytes [45]. The CaMKII has a short term effect which is related to the maintenance of the excitation-contraction coupling in the heart [46] as well as a long term effect regarding the gene transcription in the cardiomyocytes [47]. The activity of the CaMKII increases markedly in MI and failing hearts and, accordingly, it promotes the process of cardiac hypertrophy and inflammation. On the other hand, cardiac hypertrophy is also related to redox signaling that uncouple CaMKII activation from Ca2+/calmodulin dependence. This is why CaMKII could represent a nodal point for integrating inflammatory and hypertrophic signaling in the cardiomyocytes [48].

Activity of the transcription factor NF-κB has long been thought to increase in cardiac hypertrophy. The nuclear factor NF-κB is considered as a prototypical proinflammatory signaling pathway [49] which has fundamental roles in immunity in addition to regulating the expression of genes controlling cell survival. There are two ways for the activation of the nuclear factor NF-κB: canonical (classical) and noncanonical pathways [50]. Canonical (classical) signaling uses the RelA, p50, and c-Rel subunits. Meanwhile the noncanonical pathway is mediated by RelB and p100/p52. Previous studies have proposed a correlation between canonical NF-κB signaling and the susceptibility and progression of cardiac disease by observing the increased level of RelA in failing hearts and the association between NFKB1 gene polymorphisms and the increased susceptibility for developing cardiac hypertrophy [51].

CONCLUSION

Cardiac hypertrophy is a ubiquitous and complex phenotype which is caused by the interactions between multiple genetics and non-genetic factors. Different receptors, molecular signaling pathways and transcription factors are involved in the pathogenesis process of cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. Oxidative stress is considered a major stimulant for the signal transduction in cardiomyocytes, including inflammatory cytokines, and MAP kinase. Signal transduction plays a significant role in controlling cell fate either in apoptosis or necrosis, and thus, cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. The understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms which are involved in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling process is crucial for the development of new therapeutic plans, especially that the mortality rates related to cardiac remodeling/dysfunction remains high.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Jordan University of Science and Technology for the librarian support.

List of Abbreviations

- AKAPs

A-kinase Anchoring Proteins

- Ang II

Angiotensin II

- AT-1

Angiotensin II Type 1

- β-AR

Beta-adrenergic Receptor

- CaMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin Dependent Protein Kinase

- CVD

Cardiovascular Disease

- ETC

Electron Transport Chain

- ERK

Extracellular Signal- regulated Kinases

- H2O2

Hydrogen Peroxide

- OH

Hydroxyl Radical

- JNK

Jun Nuclear Kinase

- LV

Left Ventricular

- LTP

Long Term Potentiation

- MAPKS

Mitogen- activated Protein Kinases

- mAKAP

Muscle – specific A-kinase Anchoring Protein

- NADPH

Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Oxidase

- NO

Nitric Oxide

- NOS II/NOS III

Nitric Oxide Synthase

- NOS

Nitric Oxide Synthase

- PTKs

Non-receptor Protein Kinases

- NF-KB

Nuclear Factor KB

- ONOO-

Peroxynitrite Anion

- P13K

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PKA

Protein Kinase A

- PKB

Protein Kinase B

- PKC

Protein Kinase C

- PKC

Protein Kinase C

- PTPs

Protein Phosphatases

- RNS

Reactive Nitrogen Species

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- O2-

Superoxide

- SNS

Sympathetic Nervous System

- TNF-α

Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klann E. Cell-permeable scavengers of superoxide prevent long-term potentiation in hippocampal area CA1. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;80(1):452–457. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knapp L.T., Klann E. Potentiation of hippocampal synaptic transmission by superoxide requires the oxidative activation of protein kinase C. J. Neurosci. 2002;22(3):674–683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00674.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukui K., Onodera K., Shinkai T., Suzuki S., Urano S. Impairment of learning and memory in rats caused by oxidative stress and aging, and changes in antioxidative defense systems. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001;928:168–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forster M.J., Dubey A., Dawson K.M., Stutts W.A., Lal H., Sohal R.S. Age-related losses of cognitive function and motor skills in mice are associated with oxidative protein damage in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93(10):4765–4769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Planavila A., Redondo-Angulo I., Ribas F., et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 protects the heart from oxidative stress. Cardiovasc. Res. 2015;106(1):19–31. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J.B., Hama S., Hough G., et al. Heart failure is associated with impaired anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of high-density lipoproteins. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013;112(11):1770–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brigelius-Flohe R. Tissue-specific functions of individual glutathione peroxidases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;27(9-10):951–965. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brigelius-Flohe R., Wingler K., Muller C. Estimation of individual types of glutathione peroxidases. Methods Enzymol. 2002;347:101–112. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)47011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halliwell B. Drug antioxidant effects. A basis for drug selection? Drugs. 1991;42(4):569–605. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199142040-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markesbery W.R., Carney J.M. Oxidative alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 1999;9(1):133–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maulik S.K., Kumar S. Oxidative stress and cardiac hypertrophy: A review. Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 2012;22(5):359–366. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2012.666650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert A.J., Brand M.D. Reactive oxygen species production by mitochondria. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009;554:165–181. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-521-3_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mailloux R.J. Teaching the fundamentals of electron transfer reactions in mitochondria and the production and detection of reactive oxygen species. Redox Biol. 2015;4C:381–398. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guzy R.D., Hoyos B., Robin E., et al. Mitochondrial complex III is required for hypoxia-induced ROS production and cellular oxygen sensing. Cell Metab. 2005;1(6):401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stowe D.F., Camara A.K. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in excitable cells: Modulators of mitochondrial and cell function. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11(6):1373–1414. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valko M., Leibfritz D., Moncol J., Cronin M.T., Mazur M., Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007;39(1):44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J.M., Gall N.P., Grieve D.J., Chen M., Shah A.M. Activation of NADPH oxidase during progression of cardiac hypertrophy to failure. Hypertension. 2002;40(4):477–484. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000032031.30374.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seddon M., Looi Y.H., Shah A.M. Oxidative stress and redox signalling in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Heart. 2007;93(8):903–907. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.068270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto E., Lai Z.F., Yamashita T., et al. Enhancement of cardiac oxidative stress by tachycardia and its critical role in cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. J. Hypertens. 2006;24(10):2057–2069. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000244956.47114.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tigchelaar W., Yu H., de Jong A.M., et al. Loss of mitochondrial exo/endonuclease EXOG affects mitochondrial respiration and induces ROS-mediated cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2015;308(2):C155–C163. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00227.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baradaran A., Nasri H., Rafieian-Kopaei M. Oxidative stress and hypertension: Possibility of hypertension therapy with antioxidants. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2014;19(4):358–367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brito R., Castillo G., Gonzalez J., Valls N., Rodrigo R. Oxidative stress in hypertension: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2015;123(6):325–335. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1548765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conti F.F., Brito Jde O., Bernardes N., et al. Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction and oxidative stress induced by fructose overload in an experimental model of hypertension and menopause. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2014;14:185. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinha N., Dabla P.K. Oxidative stress and antioxidants in hypertension -A current review. Curr. Hypertens. Rev. 2015;11(2):132–142. doi: 10.2174/1573402111666150529130922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodrigo R., Gonzalez J., Paoletto F. The role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 2011;34(4):431–440. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y., Lei S., Gao X., et al. PKCbeta inhibition with ruboxistaurin reduces oxidative stress and attenuates left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2012;122(4):161–173. doi: 10.1042/CS20110176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molkentin J.D., Lu J.R., Antos C.L., et al. A calcineurin-dependent transcriptional pathway for cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 1998;93(2):215–228. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81573-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodge-Kafka K.L., Kapiloff M.S. The mAKAP signaling complex: Integration of cAMP, calcium, and MAP kinase signaling pathways. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2006;85(7):593–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pare G.C., Bauman A.L., McHenry M., Michel J.J., Dodge-Kafka K.L., Kapiloff M.S. The mAKAP complex participates in the induction of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy by adrenergic receptor signaling. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 23):5637–5646. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schirone L., Forte M., Palmerio S., et al. A review of the molecular mechanisms underlying the development and progression of cardiac remodeling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017;2017:3920195. doi: 10.1155/2017/3920195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Florea V.G., Cohn J.N. The autonomic nervous system and heart failure. Circ. Res. 2014;114(11):1815–1826. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohn J.N., Ferrari R., Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling--concepts and clinical implications: A consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. Behalf of an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000;35(3):569–582. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehta P.K., Griendling K.K. Angiotensin II cell signaling: Physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007;292(1):C82–C97. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johar S., Cave A.C., Narayanapanicker A., Grieve D.J., Shah A.M. Aldosterone mediates angiotensin II-induced interstitial cardiac fibrosis via a Nox2-containing NADPH oxidase. FASEB J. 2006;20(9):1546–1548. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4642fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delcayre C., Swynghedauw B. Molecular mechanisms of myocardial remodeling. The role of aldosterone. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2002;34(12):1577–1584. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Billet S., Aguilar F., Baudry C., Clauser E. Role of angiotensin II AT1 receptor activation in cardiovascular diseases. Kidney Int. 2008;74(11):1379–1384. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrario C.M. Cardiac remodelling and RAS inhibition. Ther. Adv. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016;10(3):162–171. doi: 10.1177/1753944716642677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carnegie G.K., Means C.K., Scott J.D. A-kinase anchoring proteins: From protein complexes to physiology and disease. IUBMB Life. 2009;61(4):394–406. doi: 10.1002/iub.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carnegie G.K., Burmeister B.T. A-kinase anchoring proteins that regulate cardiac remodeling. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2011;58(5):451–458. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31821c0220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Griffiths-Jones S., Grocock R.J., van Dongen S., Bateman A., Enright A.J. miRBase: MicroRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D140–D144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doetschman T., Azhar M. Cardiac-specific inducible and conditional gene targeting in mice. Circ. Res. 2012;110(11):1498–1512. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.265066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin Z., Murtaza I., Wang K., Jiao J., Gao J., Li P.F. miR-23a functions downstream of NFATc3 to regulate cardiac hypertrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(29):12103–12108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811371106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oury C., Servais L., Bouznad N., Hego A., Nchimi A., Lancellotti P. MicroRNAs in valvular heart diseases: Potential role as markers and actors of valvular and cardiac remodeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17(7):E1120. doi: 10.3390/ijms17071120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang J., Liew O.W., Richards A.M., Chen Y.T. Overview of microRNAs in cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17(5):E749. doi: 10.3390/ijms17050749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mattiazzi A., Bassani R.A., Escobar A.L., et al. Chasing cardiac physiology and pathology down the CaMKII cascade. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015;308(10):H1177–H1191. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00007.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grimm M., Brown J.H. Beta-adrenergic receptor signaling in the heart: Role of CaMKII. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010;48(2):322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh M.V., Kapoun A., Higgins L., et al. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II triggers cell membrane injury by inducing complement factor B gene expression in the mouse heart. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119(4):986–996. doi: 10.1172/JCI35814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh M.V., Anderson M.E. Is CaMKII a link between inflammation and hypertrophy in heart? J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 2011;89(6):537–543. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0727-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lawrence T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009;1(6):a001651. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frantz S., Fraccarollo D., Wagner H., et al. Sustained activation of nuclear factor kappa B and activator protein 1 in chronic heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003;57(3):749–756. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00723-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gaspar-Pereira S., Fullard N., Townsend P.A., et al. The NF-kappaB subunit c-Rel stimulates cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2012;180(3):929–939. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]