Abstract

Background

Vancomycin is the first-line antibiotic for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative strains. The risk of vancomycin-induced acute kidney injury increases with plasma vancomycin levels. Vancomycin-induced acute kidney injury is histologically characterized by acute interstitial nephritis and/or acute tubular necrosis. However, only 12 biopsy-proven cases of vancomycin-induced acute kidney injury have been reported so far, as renal biopsy is rarely performed for such cases. Current recommendations for the prevention or treatment of vancomycin-induced acute kidney injury are drug monitoring of plasma vancomycin levels using trough level and drug withdrawal. Oral prednisone and high-flux haemodialysis have led to the successful recovery of renal function in some biopsy-proven cases.

Case presentation

We present the case of a 41-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus, who developed vancomycin-induced acute kidney injury during treatment for Fournier gangrene. His serum creatinine level increased to 1020.1 μmol/L from a baseline of 79.6 μmol/L, and his plasma trough level of vancomycin peaked at 80.48 μg/mL. Vancomycin discontinuation and frequent haemodialysis with high-flux membrane were immediately performed following diagnosis. Renal biopsy showed acute tubular necrosis and focal acute interstitial nephritis, mainly in the medullary rays (medullary ray injury). There was no sign of glomerulonephritis, but mild diabetic changes were detected. He was discharged without continuing haemodialysis (serum creatinine level, 145.0 μmol/L) 49 days after initial vancomycin administration.

Conclusions

This case suggests that frequent haemodialysis and renal biopsy could be useful for the treatment and assessment of vancomycin-induced acute kidney injury, particularly in high-risk cases or patients with other renal disorders.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Acute interstitial nephritis, Acute tubular necrosis, High-flux haemodialysis, Vancomycin

Background

Intravenous vancomycin (VCM) is the antibiotic of first choice for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and S. epidermidis infections [1]. The increasing use of higher VCM doses has led to a higher incidence of VCM-induced acute kidney injury (AKI) [2], particularly in patients with risk factors such as hospitalization in the Intensive Care Unit, obesity, and pre-existing chronic kidney disease, although most of the evidence was based on observational studies [3]. The mechanism behind VCM-induced AKI is still uncertain; however, animal models and a few biopsy-proven cases have shown that VCM could induce acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) and/or acute tubular necrosis (ATN) [4]. A common strategy for preventing and treating VCM-induced AKI is monitoring plasma VCM levels and subsequent VCM withdrawal as necessary [3]. Haemodialysis, particularly high-flux haemodialysis, may be useful in a more effective removal of VCM in some cases [5–7]. Alternatively, oral prednisone has been tested in the cases of AIN [6, 8–11]. Here we present a biopsy-proven case of VCM-induced AKI in a patient with Fournier gangrene and type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM) and review previous published cases.

Case presentation

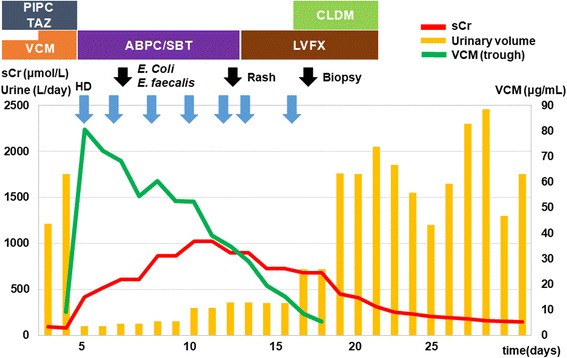

We present the case of a 41-year-old man who had been diagnosed with type 1 DM in junior high school. He was 168 cm tall and weighed 90.0 kg (body mass index, 31.9 kg/m2). His baseline serum creatinine (sCr) level was 79.6 μmol/L and his urinary protein level was 0.3 g/gCr. His blood pressure was well controlled with an aldosterone receptor blocker. DM control was poor (haemoglobin A1c 9.0–10.0%) under intensive conventional insulin therapy. His diabetic retinopathy was simple type. Pregabalin, duloxetine and mexiletine were also used for diabetic neuropathy. His family history was not significant except cerebral infarction in his grandmother. He initially visited a primary care unit because of general fatigue and high fever and was given oral levofloxacin. However, he later called an urgent care unit because of swelling and pain in his genitals. He was diagnosed with Fournier gangrene and admitted to our hospital (Fig. 1, clinical course). Table 1 showed urinary, blood and culture examination on admission. Inflammatory markers were elevated (white blood cell count 25,700/μL with left shift and C reactive protein 28.8 mg/L). Renal function was slightly abnormal (Blood urine nitrogen 22.0 mg/dL, sCr 91.1 μmol/L) and proteinuria was detected. Blood culture was negative. Escherichia coli and Enterococcus faecalis were detected from wound culture. Free air was noted in his genital area via computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 2a). He underwent debridement and received tazobactam/piperacillin (PIPC/TAZ) 4.5 g every 8 h and intravenous VCM 1.5 g every 12 h. Because his trough VCM level was still low (9.24 μg/mL, 15–20 μg/mL is for complicated infections [12]) and sCr stable (83.1 μmol/L) on day 3, intravenous VCM increased to 1.5 g every 8 h. Thereafter, he developed pitting pedal edema, weight gain (10 kg), reduced urine volume (100 mL/day), increased sCr (416.4 μmol/L) and trough VCM level (80.48 μg/mL) on day 6, which suggested VCM-induced AKI. Urinary examination results, which included N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase of 32.0 U/L, α1-microgloblin of 25.7 mg/L, and β2-microgloblin of 1800 μg/L, were also consistent with AKI. CT scan showed no signs of hydronephrosis or renal atrophy (Fig. 2b). Gallium scintigraphy showed significant accumulation in both kidneys (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 1.

Clinical course for the treatment of Fournier gangrene and vancomycin-induced acute kidney injury in a 41-year-old man. The vertical biaxis shows the serum creatinine level (sCr, red), urinary volume (yellow), and plasma trough level of vancomycin (green). Intravenous vancomycin dosages were 3.0 g/day, then increased to 4.5 g/day. VCM, vancomycin; HD, haemodialysis, PIPC/TZA, Piperacillin/Tazobactam; ABPC/SBT, Ampicillin/Sulbactam; LVFX, Levofloxacin; CLDM, Clindamycin

Table 1.

Laboratory data on admission

| Complete blood cell count | |

| White blood cell (/μL) | 25,700 |

| Red blood cell (× 104/μL) | 476 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.6 |

| Haematocrit (%) | 38.6 |

| Platelets (× 104/μL) | 20.7 |

| Serum chemistries | |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 6.1 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.9 |

| Blood urine nitrogen (mg/dL) | 22.0 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 91.1 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 5.3 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 131 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 5.1 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 96 |

| C reactive protein (mg/dL) | 28.8 |

| Haemoglobin A1c (%) | 9.4 |

| Urinalysis | |

| PH | 5.5 |

| Specific gravity | 1.008 |

| Protein | 2+ |

| Occult blood | – |

| Red blood cell sediment | 1–4/hpf |

| White blood cell sediment | 5–9/hpf |

| Cultivation | |

| Blood culture | negative |

| Wound culture | E. coli, E. faecallis |

Fig. 2.

a Computed tomography image showing free air in the genital lesion (white arrow). b Computed tomography image showing no sign of hydronephrosis or renal atrophy. c Gallium scintigraphy showing significant accumulation in both kidneys (yellow arrows)

VCM and PIPC/TAZ were switched to ampicillin/sulbactam (ABPC/SBT), and frequent haemodialysis was performed on days 6–17, a total of seven times over 12 days (seven 4-h sessions with a blood flow rate of 120–150 mL/min and dialysate flow rate of 500 mL/min). Ethylene vinyl alcohol membrane was used on days 6 and 7, whereas polysulfone membrane was used on days 9, 11, 12, 14, and 17. His urine volume began to increase as his plasma VCM levels gradually decreased. A renal biopsy was performed on day 18 to rule out other renal disorders and evaluate for diabetic nephropathy. ABPC/SBT was switched to ciprofloxacin on day 13 because of a rash that developed mainly on his abdomen and back, and clindamycin was added on days 16–22. He was discharged on day 49 without haemodialysis and antibiotics (sCr, 145.0 μmol/L). Eight months later, his sCr was decreased to 109.6 μmol/L.

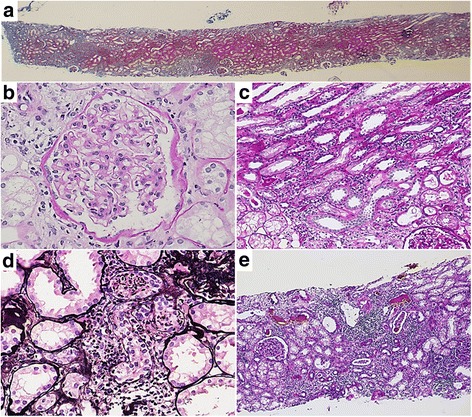

Renal biopsy

The specimen included 16 glomeruli with cortex (no medulla). Subcapsular and medullary ray fibrosis was found in 10% of the specimen on Masson staining (Fig. 3a). Glomeruli showed no sclerotic or inflammatory changes, but mild mesangial expansion without significant depositions of immunoglobulin or complement in immunofluorescence was found. Nodular lesions were not detected (Fig. 3b). Focal but severe AIN (Fig. 3c) and tubular epithelium injury with nuclear denudation or tubular dilatation (ATN) (Fig. 3d) were detected. Interstitial monocyte infiltration and tubulitis were mainly distributed in the medullary ray lesions (Fig. 3e). There were no obvious eosinophilic infiltrations or granular lesions in the specimen. Mild intimal fibrosis was found in some of the small interlobular arteries, and mild hyalinosis was also noted in an arteriole. In summary, the kidney biopsy showed that ATN and focal AIN with mild diabetic nephropathy.

Fig. 3.

Kidney biopsy slide specimen showing: a subcapsular and medullary ray fibrosis in 10% of the specimen, b mild mesangial expansion in the glomeruli, c focal but severe lymphocyte infiltration and tubulitis, d tubular epithelium injury with nuclear denudation or tubular dilatation, and e interstitial monocyte infiltration and tubulitis mainly distributed in the medullary ray lesion [a, Masson trichrome, × 2; b, c, Periodic acid–Schiff, × 40 and × 20, respectively; d, Periodic acid–methenamine–silver, × 40; e, Tamm–Horsfall protein staining added on Periodic acid–Schiff, × 10]

Discussion

In general, an AKI episode is an independent risk factor for end-stage renal disease and death, and patients with pre-existing chronic kidney disease (CKD) are at higher risk for long-term mortality and dialysis after hospital discharge [13].

The first case series of VCM-induced AKI was reported in 1958 [14]. The incidence of VCM-induced nephrotoxicity was reported in approximately 5% of patients [2]. VCM-induced AKI is initially diagnosed when 50% sCr (or 44.2 μmol/l) elevation from baseline is detected in at least two different time points after administration of VCM treatment [15]. However, many of recent studies are committed to the definition and classification of AKI of RIFLE, AKIN and KDIGO criteria [16–18].

Plasma VCM level should be controlled in the appropriate range to prevent VCM-induced AKI. Plasma VCM level could be measured with therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), such as VCM trough and area under the curve (AUC). However, VCM trough and AUC might be insufficient for prediction of VCM-induced AKI in large population study [19]. Moreover, available TDM guidelines still need optimizations to establish a more reliable VCM-TDM strategy in accordance with risk factors [20]. Previous studies showed that minimal sCr elevation is associated with prognosis of AKI [21], and intensive monitoring of urine output could be useful for AKI diagnosis and better outcomes [22]. More careful monitoring should be used to detect AKI as soon as possible in VCM usage.

Although VCM nephrotoxicity was well known in clinical settings, only 12 cases of biopsy-proven VCM-induced AKI have been reported so far as renal biopsy is rarely performed for such cases (Table 2) [4–11, 23–25]. Most of them showed AIN, and three cases showed ATN. Renal biopsy in our case (peak sCr, 1020.1 μmol/L) and one of the reported cases (peak sCr, 1034.3 μmol/L) revealed ATN and AIN. Diabetic nephropathy [11], IgA nephropathy [11], and lupus nephritis [25] were found simultaneously.

Table 2.

Cases of biopsy-proven vancomycin induced AKI

| Case | Patient Characteristics (age/sex/infections) |

Complications | Baseline Cr (μmol/L) |

Peak Cr (μmol/L) |

Biopsy | Treatment (+ VCM withdrawal) |

Final follow up Cr (μmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ①4 | 79/F CNS bacteremia |

79.6 – 97.2 | 1034.3 | ATN+AIN | PSL | 88.4 | |

| ②5 |

67/M

S. aureus endocarditis |

132.6 –176.8 | 583.4 | AIN | HD | death | |

| ③6 | 70/M MRSA abscess |

TEN | 106.1 | 848.6 | AIN | HD+PSL | death |

| ④7 | 8/M Infection of VP shunt |

35.3 | 176.8 | ATN | HD | 35.4 | |

| ⑤8 | 63/M Sternal wound dehiscence |

CAD | 53.0 – 132.6 | 839.8 | AIN | HD+PSL | 106.1 |

| ⑥9 | 44/M Osteomyelitis |

DM | ND | 751.4 | AIN | HD+PSL | 247.5 |

| ⑦10 | 51/M Osteomyelitis |

79.6 | 503.9 | AIN | PSL | 114.9 | |

| ⑧11 | 45/F Osteomyelitis |

Type 2 DM | 106.1 | 203.3 | AIN DMN |

PSL | 168.0 |

| ⑨11 | 61/M Surgical infection |

Spinal stenosis | 88.4 | 627.6 | AIN IgAN |

PSL | 212.2 |

| ⑩23 |

35/M

S. aureus loculated pleural effusion |

ND | 574.6 | AIN | ND | 114.9 | |

| ⑪24 | 71/F MRSA bacteremia |

70.6 | 397.8 | ATN | HD | HD | |

| ⑫25 | 13/M Toxic skin syndrome |

SLE | 106.1 | 495.0 | ATN LN type V |

PSL (for LN) |

79.6 |

| This case | 41/M Fornier disease |

Type1 DM | 79.6 | 1020.1 | ATN+AIN DMN |

HD | 109.6 |

M male, F female, VP ventriculoperitoneal, MRSA methicillin - resistant Staphylococcus aureus, CNS coagulase negative Staphylococcus aureus, DM diabetes, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, TEN toxic epidermal necrolysis, CAD coronary artery disease, ND not described, Cr creatinine, LN lupus nephritis, AIN acute interstitial nephritis, ATN acute tubular necrosis, HD hemodialysis, VCM vancomycin, PSL prednisolone

Although the mechanism of kidney injury is still unknown, VCM induced oxidative stress that promotes reactive oxygen species was thought to be the main one [26]. Animal study showed that VCM induced renal tubular injuries were ameliorated by the use of antioxidants [26, 27]. An allergic reaction could be responsible to VCM induced AIN [11]. A case of recurrent AIN after secondary challenge of VCM also implied such an immunologic reaction [28].

Meanwhile, it is difficult to define what is cause of VCM-induced AKI in clinical cases; synergistic toxicity of VCM and other antibiotics such as PIPC/TAZ, cefepime, aminoglycoside should be considered in the current case as shown in previous studies [29–31]. Other multiple drug usages could affect VCM pharmacokinetics. Furthermore, VCM-induced AKI is more likely to occur in pre-existing renal disease [3].

In our case, nephrotoxicity of VCM could be enhanced in combination with PIPC/TAZ, which can decrease VCM clearance, and elevate plasma VCM level [29]. Renal biopsy was necessary in our case, because we need to differentiate other renal diseases such as glomerulonephritis and diabetic nephropathy for proteinuria on admission and continuous oliguria. The renal biopsy showed ATN and localized AIN with mild diabetic nephropathy, which suggested that the main cause of AKI was considered to be VCM induced ATN and AIN. AIN caused by ABPC/SBT should be considered, because this case showed rash. Although ABPC/SBT frequently cause rash (1.2%), severe AKI is rare in ABPC/SBT usage by itself [32, 33].

In previous cases of biopsy-proven VCM-induced AKI, diffuse or focal ATN was related to relatively higher levels of sCr [4, 7, 24, 25], and one case with severe ATN needed to continue haemodialysis for at least 2 months after treatments [24]. Oral prednisone therapy has been attempted in AIN cases [6, 8–11], but has not been established for VCM-induced AKI. Oral prednisone therapy was not attempted in our case because he had poor controlled DM and frontier gangrene. Renal biopsy result (localized AIN) was commit to our decision on no steroid use in the retrospective view. However, if AIN lesion is more expanded, oral prednisone should be considered to treat not only for VCM-induced AKI but for possible side effects of ABPC/SBT.

Haemodialysis, particularly high-flux haemodialysis, might be useful in a more effective removal of VCM in some cases [5–7]. In paediatric cases, reducing plasma VCM levels by high-flux haemodialysis contributed to the good renal prognosis [7, 34]. In our case, frequent haemodialysis with high-flux filters was performed seven times over 12 days, and urine volume was increased right after plasma vancomycin level was decreased (Fig. 1).

VCM is composed of a large glycopeptide compound (molecular weight, 1450 Da) [35] with a heterogeneous protein-binding rate (24.3–64%) [36]. Although conventional haemodialysis membranes such as cuprophan cannot adequately remove VCM (removal rate, 6%) [37], high-flux filters such as polysulphone, polynitrile, and polymethylmethacrylate can remove VCM from patients more effectively (35–46%) [37, 38]. However, rebounding of plasma VCM 3–6 h after haemodialysis was also reported [37], which suggests that frequent haemodialysis could be more useful. In our case, removal rates of plasma VCM were 10.3–20.3% using ethylene vinyl alcohol membrane and 13.2–35.2% using polysulfone membrane.

Conclusion

In summary, we present an adult patient with type 1 DM who developed VCM-induced AKI during treatment for Fournier gangrene. Early diagnosis and treatment led to the successful recovery of his renal function. This case suggests that more careful VCM-TDM and intensive monitoring of sCr and urinary output to detect AKI should be considered in VCM usage. For the diagnosis, renal biopsy of VCM induced AKI is useful to assessment prognostic and therapeutic option in cases at a high risk or those with other renal disorders. For the treatment, frequent haemodialysis could be useful in high concentration plasma VCM.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hideki Nakayama and Kaori Kumada for their technical support.

The authors would like to thank Enago (https://www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ABPC/SBT

Ampicillin/sulbactam

- AIN

Acute interstitial nephritis

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- ATN

Acute tubular necrosis

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- CT

Computed tomography

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- PIPC/TAZ

Tazobactam/piperacillin

- sCr

Serum creatinine

- VCM

Vancomycin

Authors’ contributions

AS performed the literature review, wrote the manuscript, and was a treating physician for the patient. KK wrote the manuscript, and analysed pathological data. SM, TN, MK supported data collection. ST, JK, YN supported interpretation pathological examination. MM, MO, KN and TM supported in writing this case report and revised it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Anri Sawada, Phone: +81-3-3353-8111, Email: anri-sawada@nms.ac.jp.

Kunio Kawanishi, Email: kukawanishi@ucsd.edu.

Shohei Morikawa, Email: morikawa.shohei@kameda.jp.

Toshihiro Nakano, Email: t.nakano.dr@gmail.com.

Mio Kodama, Email: mio.dama1113@hotmail.co.jp.

Mitihiro Mitobe, Email: mitobe.michihiro@kameda.jp.

Sekiko Taneda, Email: sekikosekiko@gmail.com.

Junki Koike, Email: j2koike@marianna-u.ac.jp.

Mamiko Ohara, Email: oharam-tky@umin.net.

Yoji Nagashima, Email: nagashima.yoji@twmu.ac.jp.

Kosaku Nitta, Email: knitta@twmu.ac.jp.

Takahiro Mochizuki, Email: mochizuki.takahiro@kameda.jp.

References

- 1.Levine DP. Vancomycin: a history. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;4:S5–12. doi: 10.1086/491709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farber BF, Moellering RC., Jr Retrospective study of the toxicity of preparations of vancomycin from 1974 to 1981. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983;23:138–141. doi: 10.1128/AAC.23.1.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bamgbola O. Review of vancomycin-induced renal toxicity: an update. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2016;7:136–147. doi: 10.1177/2042018816638223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Htike NL, Santoro J, Gilbert B, Elfenbein IB, Teehan G. Biopsy-proven vancomycin-associated interstitial nephritis and acute tubular necrosis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2012;16:320–324. doi: 10.1007/s10157-011-0559-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Codding CE, Ramseyer L, Allon M, Pitha J, Rodriguez M. Tubulointerstitial nephritis due to vancomycin. Am J Kidney Dis. 1989;14:512–515. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(89)80152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu SI. Biopsy-proved acute tubulointerstitial nephritis and toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with vancomycin. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:1233–1239. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.15.1233.33901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wicklow BA, Ogborn MR, Gibson IW, Blydt-Hansen TD. Biopsy-proven acute tubular necrosis in a child attributed to vancomycin intoxication. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:1194–1196. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wai AO, Lo AM, Abdo A, Marra F. Vancomycin-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:1160–1164. doi: 10.1345/aph.17448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong S, Valderrama E, Mattana J, Shah HH, Wagner JD, Esposito M, Singhal PC. Vancomycin-induced acute granulomatous interstitial nephritis: therapeutic options. Am J Med Sci. 2007;334:296–300. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3180a6ec1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salazar MN, Matthews M, Posadas A, Ehsan M, Graeber C. Biopsy proven interstitial nephritis following treatment with vancomycin: a case report. Conn Med. 2010;74:139–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelfand MS, Cleveland KO, Mazumder SA. Vancomycin-induced interstitial nephritis superimposed on coexisting renal disease: the importance of renal biopsy. Am J Med Sci. 2014;347:338–340. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rybak M, Lomaestro B, Rotschafer JC, Moellering R, Jr, Craig W, Billeter M, Dalovisio JR, Levine DP. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:82–98. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu VC, Huang TM, Lai CF, Shiao CC, Lin YF, Chu TS, Wu PC, Chao CT, Wang JY, Kao TW, Young GH, Tsai PR, Tsai HB, Wang CL, Wu MS, Chiang WC, Tsai IJ, Hu FC, Lin SL, Chen YM, Tsai TJ, Ko WJ, Wu KD. Acute-on-chronic kidney injury at hospital discharge is associated with long-term dialysis and mortality. Kidney Int. 2011;80:1222–1230. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geraci JE, Heilman FR, Nichols DR, Wellman WE. Antibiotic therapy of bacterial endocarditis. VII. Vancomycin for acute micrococcal endocarditis; preliminary report. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1958;33:172–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elyasi S, Khalili H, Dashti-Khavidaki S, Mohammadpour A. Vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity: mechanism, incidence, risk factors and special populations. A literature review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:1243–1255. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Disease K. Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney inter. 2012;2:1–138. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2012.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P. Acute dialysis quality initiative workgroup. Acute renal failure - definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the second international consensus conference of the acute dialysis quality initiative (ADQI) group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204–R212. doi: 10.1186/cc2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A. Acute kidney injury network. Acute kidney injury network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haeseker M, Croes S, Neef C, Bruggeman C, Stolk L, Verbon A. Evaluation of vancomycin prediction methods based on estimated creatinine clearance or trough levels. Ther Drug Monit. 2016;38:120–126. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye ZK, Li C, Zhai SD. Guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring of vancomycin: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365–3370. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin K, Murugan R, Sileanu FE, Foldes E, Priyanka P, Clermont G, Kellum JA. Intensive monitoring of urine output is associated with increased detection of acute kidney injury and improved outcomes. Chest. 2017;152:972–979. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michail S, Vaiopoulos G, Nakopoulou L, et al. Henoch-Schoenlein purpura and acute interstitial nephritis after intravenous vancomycin administration in a patient with a staphylococcal infection. Scand J Rheumatol. 1998;27:233–235. doi: 10.1080/030097498440886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sokol H, Vigneau C, Maury E, Guidet B, Offenstadt G. Biopsy-proven anuric acute tubular necrosis associated with vancomycin and one dose of aminoside. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:1921–1922. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu CY, Wang JS, Chiou YH, Chen CY, Su YT. Biopsy proven acute tubular necrosis associated with vancomycin in a child: case report and literature review. Ren Fail. 2007;29:1059–1061. doi: 10.1080/08860220701643773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oktem F, Arslan MK, Ozguner F, Candir O, Yilmaz HR, Ciris M, Uz E. In vivo evidences suggesting the role of oxidative stress in pathogenesis of vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity: protection by erdosteine. Toxicology. 2005;215:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Im DS, Shin HJ, Yang KJ, Jung SY, Song HY, Hwang HS, Gil HW. Cilastatin attenuates vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity via P-glycoprotein. Toxicol Lett. 2017;277:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azar R, Bakhache E, Boldron A. Acute interstitial nephropathy induced by vancomycin. Nephrologie. 1996;17:327–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burgess LD, Drew RH. Comparison of the incidence of vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity in hospitalized patients with and without concomitant piperacillin-tazobactam. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:670–676. doi: 10.1002/phar.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomes D, Smotherman C, Birch A, Dupree L, Della Vecchia BJ, Kraemer DF, Jankowski CA. Comparison of acute kidney injury during treatment with vancomycin in combination with piperacillin-tazobactam or cefepime. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:662–669. doi: 10.1002/phar.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rybak M, Albrecht L, Boike S, Chandrasekar P. Nephrotoxicity of vancomycin, alone and with an aminoglycoside. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;25:679–687. doi: 10.1093/jac/25.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lode HM. Rational antibiotic therapy and the position of ampicillin/sulbactam. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;32:10–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Betrosian AP, Douzinas EE. Ampicillin-sulbactam: an update on the use of parenteral and oral forms in bacterial infections. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5:1099–1112. doi: 10.1517/17425250903145251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stidham T, Reiter PD, Ford DM, Lum GM, Albietz J. Successful utilization of high-flux hemodialysis for treatment of vancomycin toxicity in a child. Case Rep Pediatr. 2011;2011:678724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Cooper GL, Given DB. Vancomycin: a comprehensive review of 30 years clinical experience. San Diego, CA, USA: Park Row Publishers; 1986. pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butterfield JM, Patel N, Pai MP, Rosano TG, Drusano GL, Lodise TP. Refining vancomycin protein binding estimates: identification of clinical factors that influence protein binding. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4277–4282. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01674-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeSoi CA, Sahm DF, Umans JG. Vancomycin elimination during high-flux hemodialysis: kinetic model and comparison of four membranes. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;20:354–360. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(12)70298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foote EF, Dreitlein WB, Steward CA, Kapoian T, Walker JA, Sherman RA. Pharmacokinetics of vancomycin when administered during high flux hemodialysis. Clin Nephrol. 1998;50:51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.