Abstract

Background

Haplotype assembly is the task of reconstructing haplotypes of an individual from a mixture of sequenced chromosome fragments. Haplotype information enables studies of the effects of genetic variations on an organism’s phenotype. Most of the mathematical formulations of haplotype assembly are known to be NP-hard and haplotype assembly becomes even more challenging as the sequencing technology advances and the length of the paired-end reads and inserts increases. Assembly of haplotypes polyploid organisms is considerably more difficult than in the case of diploids. Hence, scalable and accurate schemes with provable performance are desired for haplotype assembly of both diploid and polyploid organisms.

Results

We propose a framework that formulates haplotype assembly from sequencing data as a sparse tensor decomposition. We cast the problem as that of decomposing a tensor having special structural constraints and missing a large fraction of its entries into a product of two factors, U and ; tensor reveals haplotype information while U is a sparse matrix encoding the origin of erroneous sequencing reads. An algorithm, AltHap, which reconstructs haplotypes of either diploid or polyploid organisms by iteratively solving this decomposition problem is proposed. The performance and convergence properties of AltHap are theoretically analyzed and, in doing so, guarantees on the achievable minimum error correction scores and correct phasing rate are established. The developed framework is applicable to diploid, biallelic and polyallelic polyploid species. The code for AltHap is freely available from https://github.com/realabolfazl/AltHap.

Conclusion

AltHap was tested in a number of different scenarios and was shown to compare favorably to state-of-the-art methods in applications to haplotype assembly of diploids, and significantly outperforms existing techniques when applied to haplotype assembly of polyploids.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12864-018-4551-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Haplotype assembly, Tensor decomposition, Iterative algorithm

Background

Fast and accurate DNA sequencing has enabled unprecedented studies of genetic variations and their effect on human health and medical treatments. Complete information about variations in an individual’s genome is given by haplotypes, the ordered lists of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on the individual’s chromosomes [1]. Haplotype information is of fundamental importance for a wide range of applications. For instance, when the corresponding genes on a homologous pair of chromosomes contain multiple variants, they could exhibit different gene expression patterns. In humans, this may affect an individual’s susceptibility to diseases and response to therapeutic drugs, and hence suggest directions for medical and pharmaceutical research [2]. Haplotype information also enables whole genome association studies that focus on the so-called tag SNPs [3], representative SNPs in a region of the genome characterized by strong correlation between alleles (i.e., by high linkage disequilibrium). Moreover, haplotype sequences can be used to infer recombination patterns and identify genes under positive selection [4]. In addition to the SNPs and minor structural variations found in a healthy individual’s genome, complex chromosomal aberrations such as translocations and nonreciprocal structural changes – including aneuploidy – are present in cancer cells. Cancer haplotype assembly enables identification of “driver” mutations and thus helps to understanding the mechanisms behind the disease and discovery of its genetic signatures.

Haplotype assembly from short reads obtained by high-through-put DNA sequencing requires partitioning (either directly or indirectly) the reads into K clusters (K=2 for diploids, K=3 for triploids, etc.), each collecting the reads corresponding to one of the chromosomes. If the reads were free of sequencing errors, this task would be straightforward. However, sequencing is erroneous – state-of-the-art platforms have error rates on the order of 10−3−10−2. This leads to ambiguities regarding the origin of a read and therefore renders haplotype assembly challenging. For this reason, the vast majority of haplotype assembly techniques attempts to remove the aforementioned ambiguities by either discarding or altering sequencing data; this has led to the minimum fragment removal, minimum SNP removal [5], maximum fragments cut [6], and minimum error correction formulations of the assembly problem [7]. Most of the recent haplotype assembly methods (see, e.g., [8–12]) focus on the minimum error correction (MEC) formulation where the goal is to find the smallest number of nucleotides in reads that need to be changed so that any read partitioning ambiguities would be resolved. It has been shown that finding optimal solution to the MEC formulation of the haplotype assembly problem is NP-hard [5, 12, 13]. In [14], the authors used a branch-and-bound scheme to minimize the MEC objective over the space of reads; to reduce the search space, they relied on a bound on the objective obtained by a random partition of the reads. Unfortunately, exponential growth of the complexity of this scheme makes it computationally infeasible even for moderate haplotype lengths. Integer linear programming techniques have been applied to haplotype assembly in [15], but the approach there fails at computationally difficult instances of the problem. More recently, fixed parameter tractable (FPT) algorithms with runtimes exponential in the number of variants per read [16, 17] were proposed; these methods are well-suited for short reads but become infeasible for the long ones. A dynamic programming scheme for haplotype assembly of diploids proposed in [18] is also exponential in the length of the longest read. A probabilistic dynamic programming algorithm that optimizes a likelihood function generalizing the MEC objective is developed in [10]; this method is characterized by high accuracy but is significantly slower than the previous heuristics. Authors in [9, 11] aim to process long reads by developing algorithms for the exact optimization of weighted variants of the MEC score that scale well with read length but are exponential in the sequencing coverage. These methods, along with ProbHap [10], struggle to remain accurate and practically feasible at high coverages (e.g., higher than 12 [10]).

The computational challenges of optimizing MEC score has motivated several polynomial time heuristics. In a pioneering work [19], a greedy algorithm seeking the most likely haplotypes was used to assemble haplotypes of the first complete diploid individual genome obtained via high-throughput sequencing. To compute posterior joint probabilities of consecutive SNPs, Bayesian methods relying on MCMC and Gibbs sampling schemes were proposed in [20] and [21], respectively; unfortunately, slow convergence of Markov chains that these schemes rely on limits their practical feasibility. Following an observation that haplotype assembly can be interpreted as a clustering problem, a max-cut formulation was proposed in [22]; an efficient algorithm (HapCUT, recently upgraded to HapCUT2 [23]) that solves it and significantly outperforms the method in [19] was developed and has widely been used. A flow-graph based approach in [24], HapCompass, re-examined fragment removal strategy and demonstrated superior performance over HapCUT. Other recent diploid haplotype assembly methods include a greedy max-cut approach in [25], convex optimization program for minimizing the MEC score in [26], a communication-theoretic interpretation of the problem solved via belief propagation (BP) in [27], and methods that use external reference panels such as 1000 Genomes to improve accuracy of haplotype assembly in [28, 29]. Note that deep sequencing coverage provided by state-of-the-art high-throughput sequencing platforms and the emergence of very long insert sizes in recent technologies (e.g., fosmid [25]) may enable assembly of extremely long haplotype blocks but also impose significant computational burden on the methods above.

Increased affordability, capability to provide deep coverage, and longer sequencing read lengths also enabled studies of genetic variations of polyploid organisms. However, haplotype assembly for polyploid genomes is considerably more challenging than that for diploids; to illustrate this, note that for a polyploid genome with k haplotype sequences of length m, under the all-heterozygous assumption there are (k−1)m different genotypes and at least 2(m−1)(k−1)m different haplotype phasings. In part for this reason relatively fewer methods for solving the haplotype assembly problems in polyploids have been developed. In fact, with the exception of HapCompass [24], SDhaP [26] and BP [27], the above listed methods are restricted to diploid genomes. Other techniques capable of reconstructing haplotypes for both diploid and polyploid genomes include HapTree [30], a Bayesian method to find the maximum likelihood haplotype shown to be superior to HapCompass and SDhaP (see, e.g., [31] for a detailed comparison), H-PoP [8], the state-of-the-art dynamic programming method that significantly outperforms the schemes developed in [24, 26, 30] in terms of accuracy, memory consumption, and speed, and the recently proposed matrix factorization schemes in [32, 33].

In this paper, we propose a unified framework for haplotype assembly of diploid and polyploid genomes based on sparse tensor decomposition; the framework essentially solves a relaxed version of the NP-hard MEC formulation of the haplotype assembly problem. In particular, read fragments are organized in a sparse binary tensor which can be thought of as being obtained by multiplying a matrix that contains information about the origin of erroneous sequencing reads and a tensor that contains haplotype information of an organism. The problem then is recast as that of decomposing a tensor having special structural constraints and missing a large fraction of its entries. Based on a modified gradient descent method and after unfolding the observed and haplotype information bearing tensors, an iterative procedure for finding the decomposition is proposed. The algorithm exploits underlying structural properties of the factors to perform decomposition at a low computational cost. In addition, we analyze the performance and convergence properties of the proposed algorithm and determine bounds on the minimum error correction (MEC) scores and correct phasing rate (CPR) – also referred to as reconstruction rate – that the algorithm achieves for a given sequencing coverage and data error rate. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first polynomial time approximation algorithm for haplotype assembly of diploids and polyploids having explicit theoretical guarantees for its achievable MEC score and CPR. The proposed algorithm, referred to as AltHap, is tested in applications to haplotype assembly for both diploid and polyploid genomes (synthetic and real data) and compared with several state-of-the-art methods. Our extensive experiments reveal that AltHap outperforms the competing techniques in terms of accuracy, running time, or both. It should be noted that while state-of-the-art haplotype assembly methods for polyploids assume haplotypes may only have biallelic sites, AltHap is capable of reconstructing polyallelic haplotypes which are common in many plants and some animals, are of particular importance for applications such as crop cultivation [34], and may help in reconstruction of viral quasispecies [35]. Moreover, while many state-of-the-art haplotype assembly methods are computationally intensive (e.g., [10, 15]), our extensive numerical experiments demonstrate efficacy of AltHap in a variety of practical settings.

Methods

Problem formulation

We briefly summarize notation used in the paper. Bold capital letters refer to matrices and bold lowercase letters represent vectors. Tensors are denoted by underlined bold capital letters, e.g., . M::1 and denote the frontal slice and the mode-1 unfolding of a third-order tensor , respectively. For a positive integer n, [n] denotes the set {1…,n}. The condition number of rank-k matrix M is defined as κ=σ1/σk where σ1≥⋯≥σk>0 are singular values of M. SVDk(M) denotes the rank k approximation (compact SVD) of M computed by power iteration method [36, 37].

Let denote the set of haplotype sequences of a k-ploid organism, and let R be an n×m SNP fragment matrix where n denotes the number of sequencing reads and m is the length of haplotype sequences. R is an incomplete matrix that can be thought of as being obtained by sampling, with errors, matrix M that consists of n rows; each row of M is a sequence randomly selected from among k haplotype sequences. Since each SNP is one of four possible nucleotides, we use the alphabet to describe the information in the haplotype sequences; the mapping between nucleotides and alphabet components follows arbitrary convention. The reads can now be organized into an n×m×4 SNP fragment tensor which we denote by . The (i,j,:) fiber of , i.e., a one-dimensional slice obtained by fixing the first and second indices of the tensor, represents the value of the jth SNP in the ith read. Let Ω denote the set of informative fibers of , i.e., the set of (i,j,:) such that the ith read covers the jth SNP. Define an operator as

| 1 |

is a tensor obtained by sampling, with errors, tensor having n copies of k encoded haplotype sequences as its horizontal slices. More specifically, we can write , where contains haplotype information, i.e., the jth vertical slice of , V:j:, is the encoded sequence of the jth haplotype, and U∈{0,1}n×k is a matrix that assigns each of n horizontal slices of to one of k haplotype sequences, i.e., the ith row of U, ui, is an indicator of the origin of the ith read. Let Φ={e1,…,ek}, where is the lth standard basis vector having 1 in the lth position and 0 elsewhere. The rows of U are standard unit basis vectors in , i.e., ui∈Φ, ∀i∈[n]. This representation is illustrated in Fig. 1 where the (1,1,:) fiber of specified with dashed lines is mapped to the (1,1,:) fiber of which in turn implies that in the example described in Fig. 1 we have u1=e1.

Fig. 1.

Representing haplotype sequences and sequencing reads using tensors. Tensor contains haplotype information while matrix U∈{0,1}n×k assigns each of the n horizontal slices of to one of the k haplotype sequences, i.e., the ith row of U is an indicator of the origin of the ith read

DNA sequencing is erroneous and hence we assume a model where the informative fibers in are perturbed versions of the corresponding fibers in with data error rate pe, i.e., if the (i,j,:)∈Ω fiber in takes value , Rij: with probability 1−pe equals el and with probability pe takes one of the other three possibilities. Thus, the observed SNP fragment tensor can be modeled as where is an additive noise tensor defined as

| 2 |

where the notation denotes uniform selection of a vector from . The goal of haplotype assembly can now be formulated as follows: Given the SNP fragment tensor, find the tensor of haplotype sequencesthat minimizes the MEC score.

Next, we formalize the MEC score as well as the correct phasing rate, also known as reconstruction rate, the two metrics that are used to characterize performance of haplotype assembly schemes (see, e.g., [15, 18, 38, 39]). For two alleles a1, , we define a dissimilarity function d(a1,a2) as

| 3 |

The MEC score is the smallest number of fibers in that need to be altered so that the resulting modified data is consistent with the reconstructed haplotype , i.e.,

| 4 |

The correct phasing rate (CPR), also referred to as the reconstruction rate, can conveniently be written using the dissimilarity function d(.,.). Let denote the tensor of true haplotype sequences. Then

| 5 |

where is a one-to-one mapping from lateral slices of to those of , i.e., a one-to-one mapping from the set of reconstructed haplotypes to the set of true haplotypes.

We now describe our proposed relaxation of the MEC formulation of the haplotype assembly problem. Let pi∈[k], ∀i∈[n] be defined as . Notice that for any j such that d(Rij:,Vjp:)=1, . Therefore, by denoting where Ωi the set of informative fibers for the ith read we obtain

| 6 |

where (a) follows from the definition of the Frobenius norm and vec(.) in (b) denotes the vectorization of its argument. Let ep be the pth standard unit vector ∀p∈[k]. It is straightforward to observe that the last equality in (6) can equivalently be written as

where is the mode-1 unfolding of the tensor . Hence,

Let U∈{0,1}n×k be the matrix such that for its ith row it holds that . In addition, notice that vec(Ri::) is the ith row of . Therefore, from the definition of the Frobenius norm and the fact that we obtain

| 7 |

The optimization problem in (7) is NP-hard since the entries of are binary and the objective function is non-convex. Relaxing the binary constraint to , ∀i∈[4m],∀j∈[k], where , results in the following relaxation of the MEC formulation,

| 8 |

The new formulation can be summarized as follows. We start by finding the so-called mode-1 unfolding of tensors and and denote the decomposition , as illustrated in Fig. 2. As implied by the figure, after unfolding, the entries of the (1,1,:) fiber are mapped to four blocks of and that correspond to the frontal slices of tensors and , respectively. Then, to determine the haplotype sequence that minimizes the MEC score, one needs to solve (8) and find the optimal tensor decomposition.

Fig. 2.

Representing haplotype sequences and sequencing reads using unfolded tensors. Matrix contains haplotype information while matrix U∈{0,1}n×k assigns each of the n rows of to one of the k haplotype sequences, i.e., the ith row of U is an indicator of the origin of the ith read

The AltHap algorithm

Although the objective function in (8), i.e.,

is convex in each of the factors when the other factor is fixed, is generally nonconvex. To facilitate computationally efficient search for the solution of (8), we rely on a modified gradient search algorithm which exploits the special structures of U and and iteratively updates the estimates starting from some initial point . More specifically, given the current estimates , the update rules are

| 9 |

| 10 |

where denotes the partial derivative of evaluated at , α is a judiciously chosen step size, and denotes the projection operator onto . Notice that the optimization in (9) is done by exhaustively searching over k vectors in Φ. Since the number of haplotypes k is relatively small, the complexity of the exhaustive search (9) is low. The proposed scheme is formalized as Algorithm 1.

Note that AltHap differs from a previously proposed SCGD algorithm in [32] as follows: (i) AltHap’s novel representation of haplotypes and sequencing reads using binary tensors provides a unified framework for haplotype assembly of diploids as well as biallelic and polyallelic polyploids. The method in [32] is not capable of performing haplotype assembly of polyallelic polyploid genomes. (ii) Unlike [32], AltHap exploits the fact that is composed of binary entries by imposing the constraint in the MEC relaxation in (8). As our results in Section 5 demonstrate, this leads to significant performance improvements of AltHap over SCGD in a variety of settings. (iii) Lastly, in Section 4 we provide analysis of the global convergence of AltHap and derive explicit analytical bounds on its achievable performance. Such performance guarantees do not exist for the method in [32].

Convergence analysis of AltHap

In this section, we analyze the convergence properties of AltHap and provide performance guarantees in different scenarios.

In the Additional file 1 we show that, a judicious choice of the step size α according to

| 11 |

where C∈(0,2) is a constant, guarantees that the value of the objective function in (8) decreases as one alternates between (9) and (10), which in turn implies that AltHap converges. The key observation that leads to this result is that is a convex function in each of the factor matrices and that is a convex set; hence the projection in (10) leads to a reduction of in each iteration t.

It is important however to determine the conditions under which the stationary point of AltHap coincides with the global optima of (8). To this end, we first provide the definition of incoherence of matrices [40].

Definition 1

A rank-k matrixwith singular value decompositionis incoherent with parameterif for every 1≤i≤n, 1≤j≤m

| 12 |

Let each fiber in MT be observed uniformly with probably p. Let Csnp=△mp denote the expected number of SNPs covered by each read, and Cseq=△np denote the expected coverage for each of the haplotype sequences. Theorem 1 built upon the results of [41–43] states that with an adequate number of covered SNPs, the solution found by AltHap reconstructs up to an error term that stems from the existence of errors in sequencing reads.

Theorem 1

Assume is μ-incoherent. Suppose the condition number of is κ. Then there exist numerical constants C0,C1>0 such that if Ω is uniformly generated at random and

| 13 |

with probability at least , the solution found by AltHap satisfies

| 14 |

The proof of Theorem 1 relies on a coupled perturbation analysis to establish a certain type of local convexity of the objective function around the global optima. Thus, under (13) there is no other stationary point around the global optima and hence, starting from a good initial point, AltHap converges globally. We employ the initialization procedure suggested by [42] – summarized in the initialization step of Algorithm 1 – which is based on a low cost singular value decomposition of using power method [36, 37] and with high probability lies in the described convexity region of .

Remark 1

Under the assumption of 1, the Condition specifies a lower bound on the expected number of covered SNPs, Csnp, that is required for the exact recovery of in the idealistic error-free scenario, i.e., for pe=0. With higher sequencing coverage, more SNPs are covered by the reads and hence Csnp required for accurate haplotype assembly scales with Cseq along with other parameters. Moreover, the term on the right hand side of (14) is the bound on the error of the solution generated by AltHap which increases with the sequencing error rate pe and ploidy k, and decreases with Csnp and the number of reads n, as expected.

Remark 2

If is well-conditioned, i.e., is characterized by a small incoherence parameter μ and a small condition number κ, the recovery becomes easier; this is reflected in less strict sufficient condition (13) and improved achievable performance (14). In fact, as we verified in our simulation studies, by using the proposed framework for haplotype assembly, the parameters μ and κ associated with are close to 1 (the ideal case). Theorem 2 provides theoretical bounds on the expected MEC scores and CPR achieved by AltHap. (See Additional file 1 for the proof).

Theorem 2

Under the conditions of Theorem 1, with probability at least it holds that

| 15 |

Moreover, if the reads sample haplotype sequences uniformly, with probability at least it holds that

| 16 |

Remark 3

The bound established in (15) suggests that the expected MEC increases with the length of the haplotype sequences, sequencing error, number of haplotype sequences, and sequencing coverage. A higher sequencing coverage results in a larger fragment data which in turn leads to higher MEC scores.

Remark 4

As intuitively expected, the bound (16) suggests that AltHap’s achievable expected CPR improves with the number of sequencing reads and the SNP coverage; on the other hand, the CPR deteriorates at higher data error rates. Finally, assuming the same sequencing parameters, (16) implies that reconstruction of polyploid haplotypes is more challenging than that of diploids.

Results and discussion

We evaluated the performance of the proposed method on both experimental and simulated data, as described next. AltHap was implemented in Python and MATLAB, and the simulations were conducted on a single core Intel Xeon E5-2690 v3 (Haswell) with 2.6 GHz and 64 GB DDR4-2133 RAM. The benchmarking algorithms include Belief Propagation (BP) [27], a communication-inspired method capable of performing haplotype assembly of diploid and biallelic polyploid species, HapTree [30], integer linear programming (ILP) technique [15], SCGD [32], and H-PoP [8], the state-of-the-art dynamic programming algorithm for haplotype assembly of diploid and biallelic polyploid species shown to be superior to HapTree [30], HapCompass [24], and SDhaP [26] in terms of both accuracy and speed [8, 31]. Following the prior works on haplotype assembly (see, e.g., [15, 18, 38, 39]) we use MEC score and CPR to assess the quality of the reconstructed haplotypes. For clarity, in the tables we report the CPR percentage, i.e., CPR × 100.

Experimental data

We first tested performance of AltHap in an application to haplotype reconstruction of a data set from the 1000 Genomes Project – in particular, the sample NA12878 sequenced at high coverage using the 454 sequencing platform. In this work, we take the trio-phased variant calls from the GATK resource bundle [44] as the true haplotype sequences. We compare the MEC score, CPR, and running time achieved by AltHap to those of H-PoP, BP, HapTree, SCGD and ILP. All the algorithms used in the benchmarking study were executed with their default settings. The results are given in Table 1. As seen there, among the considered algorithms AltHap achieves the highest CPR for majority of the chromosomes (nine), followed by H-PoP and ILP (five each). As expected, ILP achieves the lowest MEC scores among all the methods but this comes at a computational cost much higher than that of AltHap. Notice that lower MEC score does not necessarily imply better CPR. MEC is the error evaluated on observed SNPs positions, i.e., the training data points, while CPR is related to the generalization error that is calculated on unobserved SNPs positions, i.e., the test data points. Since the sequencing reads are erroneous, an algorithm might over-fit while trying to minimize the MEC score.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of AltHap, H-PoP, BP, HapTree, SCGD, and ILP applied to haplotype reconstruction of the CEU NA12878 data set in the 1000 Genomes Project

| AltHap | H-PoP | BP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | CPR | MEC | t(sec) | CPR | MEC | t(sec) | CPR | MEC | t(sec) |

| 1 | 97.4 | 2011 | 11.26 | 95.7 | 2264 | 5.22 | 99.1 | 2321 | 8.17 |

| 2 | 95.3 | 2562 | 12.22 | 95.6 | 2971 | 5.65 | 89.5 | 2897 | 9.83 |

| 3 | 93.3 | 2084 | 10.38 | 91.2 | 2312 | 6.99 | 74.3 | 2367 | 8.30 |

| 4 | 96.9 | 2368 | 12.16 | 97.0 | 2648 | 5.24 | 74.8 | 2613 | 6.76 |

| 5 | 97.2 | 1924 | 9.96 | 96.6 | 2103 | 4.67 | 88.2 | 2185 | 4.76 |

| 6 | 94.9 | 3687 | 14.17 | 95.2 | 3343 | 4.93 | 88.7 | 3588 | 6.94 |

| 7 | 97.0 | 1846 | 11.19 | 92.4 | 1986 | 4.24 | 81.1 | 2073 | 7.88 |

| 8 | 96.2 | 1634 | 9.63 | 94.7 | 1848 | 4.14 | 88.5 | 1857 | 8.01 |

| 9 | 97.1 | 1272 | 6.42 | 91.0 | 1462 | 3.36 | 89.8 | 1491 | 6.13 |

| 10 | 96.8 | 1584 | 7.97 | 94.5 | 1683 | 3.67 | 90.8 | 1839 | 7.18 |

| 11 | 93.3 | 1394 | 7.45 | 91.5 | 1553 | 3.71 | 75.6 | 1586 | 6.69 |

| 12 | 92.1 | 1423 | 7.12 | 90.3 | 1570 | 3.46 | 74.4 | 1589 | 6.48 |

| 13 | 97.0 | 1269 | 4.42 | 94.1 | 1440 | 2.89 | 89.1 | 1409 | 5.38 |

| 14 | 90.3 | 857 | 9.53 | 97.1 | 974 | 2.54 | 70.0 | 995 | 4.53 |

| 15 | 97.2 | 941 | 9.42 | 97.4 | 1039 | 2.40 | 74.6 | 1063 | 3.92 |

| 16 | 96.7 | 1198 | 5.40 | 93.5 | 1192 | 2.47 | 79.7 | 1269 | 4.42 |

| 17 | 97.5 | 1146 | 4.58 | 91.1 | 1244 | 1.98 | 92.4 | 1234 | 3.15 |

| 18 | 91.0 | 860 | 4.54 | 97.6 | 893 | 2.51 | 82.0 | 942 | 3.79 |

| 19 | 97.6 | 618 | 3.32 | 97.8 | 695 | 1.82 | 98.0 | 1060 | 2.47 |

| 20 | 97.3 | 703 | 3.53 | 95.0 | 719 | 2.00 | 97.1 | 796 | 2.74 |

| 21 | 97.4 | 470 | 2.51 | 97.0 | 512 | 1.70 | 97.5 | 532 | 1.86 |

| 22 | 97.3 | 367 | 1.98 | 98.3 | 427 | 1.44 | 90.7 | 438 | 1.72 |

| Mean | 95.8 | 1464 | 7.69 | 94.8 | 1585 | 3.50 | 85.0 | 1643 | 5.51 |

| Sd | 2.27 | 780 | 3.54 | 2.54 | 790 | 1.49 | 8.94 | 793 | 2.32 |

| # best | 9 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| HapTree | SCGD | ILP | |||||||

| Chromosome | CPR | MEC | t(sec) | CPR | MEC | t(sec) | CPR | MEC | t(sec) |

| 1 | 84.1 | 2305 | 15.43 | 92.5 | 2456 | 3.62 | 95.6 | 1741 | 173.68 |

| 2 | 84.5 | 2875 | 17.59 | 92.6 | 3509 | 4.41 | 95.3 | 2219 | 190.37 |

| 3 | 85.2 | 2363 | 15.06 | 91.9 | 2498 | 3.40 | 95.6 | 1788 | 152.09 |

| 4 | 83.5 | 2604 | 18.67 | 92.7 | 3754 | 5.47 | 97.1 | 2048 | 168.56 |

| 5 | 84.8 | 2171 | 16.95 | 93.9 | 2750 | 3.54 | 95.4 | 1691 | 147.72 |

| 6 | 84.6 | 3583 | 23.86 | 93.0 | 5612 | 8.70 | 95.7 | 2643 | 181.51 |

| 7 | 84.7 | 2070 | 13.06 | 93.5 | 2826 | 3.95 | 95.4 | 1590 | 133.36 |

| 8 | 84.2 | 1838 | 14.81 | 90.7 | 1692 | 2.18 | 95.6 | 1472 | 136.60 |

| 9 | 85.1 | 1479 | 14.90 | 97.1 | 1885 | 2.94 | 95.2 | 1125 | 105.34 |

| 10 | 85.7 | 1823 | 12.13 | 92.6 | 1876 | 2.56 | 95.7 | 1354 | 120.89 |

| 11 | 83.6 | 1577 | 11.33 | 93.2 | 2265 | 2.95 | 95.2 | 1206 | 104.74 |

| 12 | 84.8 | 1589 | 9.97 | 92.3 | 1612 | 2.03 | 95.4 | 1214 | 103.88 |

| 13 | 82.8 | 1405 | 9.55 | 97.0 | 2947 | 3.31 | 95.5 | 1105 | 93.33 |

| 14 | 85.4 | 987 | 7.79 | 91.1 | 904 | 1.36 | 95.3 | 752 | 65.07 |

| 15 | 83.6 | 1061 | 7.43 | 99.1 | 1041 | 1.21 | 94.1 | 809 | 66.52 |

| 16 | 85.1 | 1273 | 8.13 | 93.0 | 1305 | 1.79 | 95.5 | 920 | 77.81 |

| 17 | 84.8 | 1230 | 6.34 | 96.7 | 2123 | 2.61 | 96.1 | 943 | 47.99 |

| 18 | 84.1 | 941 | 7.13 | 90.3 | 933 | 1.16 | 95.2 | 720 | 71.49 |

| 19 | 84.6 | 765 | 5.26 | 97.2 | 1290 | 3.25 | 96.6 | 533 | 44.32 |

| 20 | 86.9 | 795 | 6.08 | 96.8 | 949 | 1.38 | 95.8 | 612 | 54.30 |

| 21 | 86.3 | 528 | 5.05 | 94.3 | 499 | 0.63 | 95.2 | 415 | 31.82 |

| 22 | 86.9 | 436 | 4.65 | 94.1 | 422 | 0.74 | 95.2 | 316 | 31.89 |

| Mean | 84.8 | 1623 | 11.42 | 93.9 | 2052 | 2.87 | 95.5 | 1237 | 104.69 |

| Sd | 1.03 | 802 | 5.23 | 2.3 | 1222 | 1.80 | 0.57 | 612 | 50.37 |

| # best | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 17 | 5 | 22 | 0 |

The best results in each Chromosome and in all Chromosomes are in bolface font

Fosmid pool-based sequencing provides very long fragments and is characterized by much higher ratio of the number of SNPs to the number of reads than the standard data sets generated by high-throughput sequencing platforms. We consider the fosmid sequence data for chromosomes of HapMap NA12878 and again take the trio-phased variant calls from the GATK resource bundle [44] as the true haplotype sequences. We compare the performance of AltHap to those of H-PoP, BP, HapTree, SCGD and ILP and report the results in Table 2. As can be seen from Table 2, AltHap achieves the best CPR for most of the chromosomes (thirteen out of 22) followed by H-PoP (four). As with the 1000 Genome Project Data, ILP achieves the best MEC scores but is much slower and significantly inferior to AltHap in terms of CPR. Note that since HapTree could not finish assembling haplotype of the 6th chromosome in 48 hours, that result is missing from the table.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of AltHap, H-PoP, BP, HapTree, SCGD, and ILP applied to the Fosmid data set. HapTree could not finish assembling haplotype of the 6th chromosome in 48 hours

| AltHap | H-PoP | BP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | CPR | MEC | t(sec) | CPR | MEC | t(sec) | CPR | MEC | t(sec) |

| 1 | 95.5 | 9731 | 18.38 | 84.8 | 9845 | 2.13 | 87.6 | 9567 | 40.18 |

| 2 | 95.5 | 9589 | 38.89 | 90.4 | 9444 | 2.16 | 84.8 | 9698 | 42.90 |

| 3 | 91.7 | 7311 | 29.40 | 91.7 | 7182 | 1.79 | 84.7 | 7587 | 30.61 |

| 4 | 92.7 | 5508 | 26.69 | 92.6 | 5775 | 1.76 | 86.9 | 6288 | 31.10 |

| 5 | 92.0 | 6711 | 27.39 | 93.9 | 6910 | 1.95 | 86.3 | 6975 | 36.94 |

| 6 | 90.9 | 7213 | 33.68 | 88.5 | 7505 | 2.40 | 85.0 | 7590 | 41.20 |

| 7 | 90.7 | 6151 | 28.60 | 91.9 | 6829 | 1.68 | 85.8 | 6091 | 36.94 |

| 8 | 91.2 | 5927 | 23.82 | 90.2 | 6143 | 1.89 | 87.3 | 6282 | 38.87 |

| 9 | 91.8 | 5347 | 19.40 | 91.8 | 5719 | 1.76 | 85.1 | 5493 | 26.13 |

| 10 | 90.1 | 6044 | 24.07 | 92.4 | 6328 | 1.48 | 86.4 | 6503 | 27.65 |

| 11 | 90.8 | 5424 | 21.73 | 90.3 | 6432 | 1.68 | 85.8 | 5579 | 20.56 |

| 12 | 91.5 | 5456 | 24.25 | 91.4 | 5653 | 1.46 | 85.0 | 5706 | 24.19 |

| 13 | 90.4 | 3646 | 14.23 | 90.1 | 3708 | 1.54 | 82.7 | 3976 | 17.33 |

| 14 | 89.5 | 4156 | 18.64 | 89.1 | 4261 | 1.21 | 87.0 | 4004 | 14.84 |

| 15 | 90.0 | 4079 | 14.67 | 72.9 | 4001 | 1.06 | 82.3 | 4022 | 14.35 |

| 16 | 88.5 | 6197 | 26.28 | 71.5 | 6119 | 1.20 | 84.4 | 5112 | 29.51 |

| 17 | 89.7 | 4507 | 16.35 | 88.3 | 4911 | 1.22 | 87.6 | 4749 | 18.29 |

| 18 | 93.0 | 3080 | 12.68 | 90.8 | 3315 | 1.14 | 85.5 | 3457 | 13.31 |

| 19 | 85.7 | 4212 | 13.40 | 86.3 | 4115 | 0.84 | 83.5 | 3928 | 13.44 |

| 20 | 90.3 | 3512 | 13.64 | 90.0 | 4121 | 0.85 | 84.9 | 3814 | 15.97 |

| 21 | 92.7 | 1871 | 6.20 | 91.9 | 1974 | 0.68 | 87.2 | 1953 | 8.18 |

| 22 | 85.1 | 3654 | 17.24 | 87.8 | 3757 | 0.62 | 86.7 | 3910 | 14.72 |

| mean | 90.9 | 5424 | 21.35 | 88.6 | 5639 | 1.48 | 85.6 | 5558 | 25.33 |

| Sd | 2.5 | 1950 | 7.79 | 5.7 | 1934 | 0.50 | 1.5 | 1948 | 10.84 |

| # best | 13 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HapTree | SCGD | ILP | |||||||

| Chromosome | CPR | MEC | t(sec) | CPR | MEC | t(sec) | CPR | MEC | t(sec) |

| 1 | 91.5 | 9676 | 6501 | 95.1 | 10127 | 2.59 | 79.0 | 6889 | 80.33 |

| 2 | 92.3 | 9802 | 7196 | 94.5 | 9721 | 2.41 | 76.1 | 6700 | 76.60 |

| 3 | 90.7 | 7705 | 4847 | 88.6 | 7410 | 1.83 | 76.9 | 5122 | 79.50 |

| 4 | 90.8 | 6500 | 8392 | 87.6 | 5494 | 1.48 | 77.0 | 4072 | 51.49 |

| 5 | 90.8 | 7094 | 5670 | 89.6 | 7058 | 1.71 | 76.0 | 4637 | 54.39 |

| 6 | - | - | - | 90.4 | 7843 | 2.14 | 75.7 | 5248 | 63.37 |

| 7 | 91.5 | 6169 | 5589 | 89.4 | 6189 | 1.73 | 77.9 | 4174 | 46.85 |

| 8 | 91.2 | 6379 | 8316 | 87.4 | 5996 | 1.47 | 76.3 | 4301 | 53.57 |

| 9 | 91.7 | 5513 | 4465 | 90.0 | 5592 | 1.20 | 76.8 | 3974 | 42.41 |

| 10 | 88.9 | 6553 | 4838 | 92.8 | 6027 | 1.60 | 76.8 | 4508 | 59.25 |

| 11 | 90.5 | 5625 | 5183 | 90.1 | 5662 | 1.34 | 79.0 | 3903 | 45.45 |

| 12 | 91.3 | 5770 | 5654 | 90.5 | 5731 | 1.55 | 77.5 | 3907 | 48.76 |

| 13 | 89.8 | 4029 | 5367 | 87.6 | 3727 | 0.79 | 77.1 | 2669 | 32.09 |

| 14 | 90.6 | 4038 | 4103 | 92.9 | 4859 | 1.12 | 75.4 | 2814 | 39.61 |

| 15 | 90.7 | 4116 | 3357 | 87.8 | 4442 | 0.88 | 78.7 | 2903 | 33.80 |

| 16 | 94.2 | 5142 | 9683 | 95.5 | 6474 | 1.60 | 79.8 | 3844 | 62.44 |

| 17 | 93.1 | 4806 | 3003 | 97.1 | 4843 | 1.01 | 80.8 | 3448 | 42.00 |

| 18 | 91.9 | 3493 | 2303 | 88.3 | 3478 | 0.71 | 76.9 | 2337 | 32.27 |

| 19 | 92.8 | 3953 | 1984 | 82.5 | 4204 | 0.87 | 78.6 | 2707 | 33.68 |

| 20 | 90.1 | 3886 | 1529 | 94.6 | 3790 | 0.83 | 78.7 | 2783 | 31.78 |

| 21 | 92.1 | 1979 | 1410 | 90.7 | 2042 | 0.36 | 77.2 | 1367 | 16.42 |

| 22 | 92.4 | 3307 | 1351 | 90.6 | 3495 | 1.06 | 77.0 | 2422 | 60.62 |

| mean | 91.4 | 5502 | 4797.19 | 90.6 | 5645 | 1.38 | 77.6 | 3851 | 49.39 |

| Sd | 1.2 | 1998 | 2392.54 | 3.4 | 1977 | 0.56 | 1.39 | 1360 | 16.82 |

| # best | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

The best results in each Chromosome and in all Chromosomes are in bolface font

Simulated data: the diploid case

To further benchmark performance of the proposed scheme, we test it on the synthetic data from [39] often used to compare methods for haplotype assembly of diploids. These data sets emulate haplotype assembly under varied coverage, sequencing error rates and haplotype block lengths. We constrain our study to the assembly of haplotype blocks having length m=700 bp (the longest blocks in the data set). The results, averaged over 100 instances of the problem, are given in Table 3. As evident from this table, AltHap outperforms other algorithms for nearly all the combinations of data error rates and sequencing coverage and is also much faster than SCGD, ILP, BP and HapTree while being slightly slower than H-PoP. Note that ILP could only finish assembling haplotype of two settings with pe=0.1 and coverages of 5 and 8, in 48 hours. Hence, the results for other settings are missing from the table.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of AltHap, H-PoP, BP, HapTree, SCGD, and ILP on a simulated diploid data set from [39] with haplotype block length m=700. ILP could only finish assembly of haplotypes for two settings in 48 hours

| AltHap | H-PoP | BP | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error rate | Coverage | CPR | MEC | t(s) | CPR | MEC | t(s) | CPR | MEC | t(s) |

| 0.1 | 5 | 99.6 | 477 | 0.043 | 99.3 | 402 | 0.012 | 86.7 | 698 | 1.421 |

| 0.1 | 8 | 99.9 | 759 | 0.128 | 99.8 | 780 | 0.035 | 87.2 | 861 | 4.627 |

| 0.1 | 10 | 99.9 | 954 | 0.404 | 99.9 | 903 | 0.109 | 87.3 | 1130 | 13.58 |

| 0.2 | 5 | 90.9 | 941 | 0.061 | 87.7 | 1021 | 0.027 | 81.2 | 953 | 2.671 |

| 0.2 | 8 | 98.1 | 1458 | 0.141 | 88.9 | 1532 | 0.098 | 86.1 | 1847 | 6.897 |

| 0.2 | 10 | 99.1 | 1836 | 0.394 | 91.5 | 2023 | 0.201 | 86.7 | 2485 | 10.13 |

| 0.3 | 5 | 60.7 | 1228 | 0.069 | 61.8 | 1331 | 0.041 | 53.7 | 1677 | 3.235 |

| 0.3 | 8 | 67.7 | 2022 | 0.145 | 65.7 | 2250 | 0.098 | 57.2 | 2469 | 7.982 |

| 0.3 | 10 | 75.0 | 2558 | 0.375 | 71.2 | 2979 | 0.217 | 59.6 | 3114 | 15.32 |

| HapTree | SCGD | ILP | ||||||||

| Error rate | Coverage | CPR | MEC | t(s) | CPR | MEC | t(s) | CPR | MEC | t(s) |

| 0.1 | 5 | 88.6 | 491 | 2.13 | 96.6 | 523 | 0.66 | 98.8 | 467 | 471 |

| 0.1 | 8 | 88.4 | 767 | 3.82 | 99.8 | 772 | 0.84 | 99.7 | 760 | 2004 |

| 0.1 | 10 | 87.3 | 963 | 4.03 | 99.9 | 965 | 0.97 | - | - | - |

| 0.2 | 5 | 76.2 | 988 | 9.36 | 76.1 | 979 | 0.72 | - | - | - |

| 0.2 | 8 | 80.8 | 1562 | 6.69 | 91.3 | 1531 | 1.18 | - | - | - |

| 0.2 | 10 | 82.7 | 1943 | 4.20 | 95.4 | 1902 | 1.50 | - | - | - |

| 0.3 | 5 | 64.6 | 1170 | 10.21 | 57.8 | 1136 | 0.73 | - | - | - |

| 0.3 | 8 | 65.7 | 2021 | 6.17 | 63.7 | 1998 | 1.14 | - | - | - |

| 0.3 | 10 | 65.1 | 2597 | 5.74 | 67.9 | 2574 | 1.44 | - | - | - |

The best results in each simulation setting are in bolface font

Simulated data: the biallelic polyploid case

The performance of AltHap in applications to haplotype assembly for polyploids was tested using simulations; in particular, we studied how AltHap’s accuracy depends on coverage and sequencing error rate. The generated data sets consist of paired-end reads with long inserts that emulate the scenario where long connected haplotype blocks need to be assembled. We simulate sampling of the entire genome using paired-end reads and generate SNPs along the genome with probability 1 in 300. In other words, the distance between pairs of adjacent SNPs follows a geometric random variable with parameter (the SNP rate). To emulate a sequencing process capable of facilitating reconstruction of long haplotype blocks, we randomly generate paired-end reads of length 2×250 with average insert length of 10,000 bp and the standard deviation of 10%; sequencing errors are inserted using realistic error profiles [45] and genotyping is performed using a Bayesian approach [44]. At such read and insert lengths, the generated haplotype blocks are nearly fully connected. Each experiment is repeated 10 times. AltHap is compared with H-PoP, BP and SCGD. We also tried to run HapTree. However, HapTree could not finish the simulations for the considered block size in 48 hours.

Table 4 compares the CPR, MEC score, and running times of AltHap with those of H-PoP, BP and SCGD for biallelic triploid genomes with haplotype block lengths of m=1000 for several combinations of sequencing coverage and data error rates. As can be seen there, in terms of CPR AltHap outperforms all other methods in all the scenarios while in terms of MEC score it outperforms other methods in the vast majority of the scenarios. Note that unlike H-PoP’s, the complexity of AltHap scales gracefully with coverage (i.e., although H-PoP is very fast at low coverages, at the highest coverage AltHap becomes much faster than H-PoP). As can be seen in Table 6, overall CPR score (MEC score) of all algorithms decreases (increases) as the probability of error increases. This is expected – and also reflected in our theoretical results – since with higher data error rate haplotype assembly becomes more challenging. Additionally, MEC scores increases with coverage since higher coverage implies more sequencing reads. Therefore, the total number of observed SNP positions increases which in turn results in higher MEC scores.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of AltHap, H-PoP, BP, and SCGD on a simulated biallelic triploid data set with haplotype block length m=1000. HapTree could not finish the simulations in 48 hours

| AltHap | H-PoP | BP | SCGD | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Err | Cov | CPR | MEC | t(s) | CPR | MEC | t(s) | CPR | MEC | t(s) | CPR | MEC | t(s) |

| 0.002 | 10 | 98.2 | 322 | 30 | 71.5 | 3642 | 14 | 68.9 | 4210 | 132 | 69.7 | 11988 | 159 |

| 0.002 | 20 | 95.1 | 1986 | 59 | 73.1 | 7728 | 41 | 72.9 | 7762 | 416 | 51.8 | 35660 | 283 |

| 0.002 | 30 | 98.4 | 2412 | 109 | 70.8 | 12865 | 265 | 69.7 | 14751 | 1310 | 52.1 | 53248 | 422 |

| 0.01 | 10 | 91.7 | 1379 | 30 | 70.0 | 3786 | 14 | 68.1 | 4092 | 138 | 68.4 | 12108 | 161 |

| 0.01 | 20 | 97.7 | 1597 | 60 | 70.9 | 8375 | 42 | 68.9 | 8601 | 460 | 52.0 | 35606 | 295 |

| 0.01 | 30 | 98.9 | 3143 | 110 | 71.8 | 11769 | 266 | 68.1 | 15124 | 1301 | 52.7 | 53185 | 422 |

| 0.05 | 10 | 97.1 | 2802 | 31 | 70.1 | 3978 | 14 | 66.9 | 4227 | 135 | 67.5 | 13037 | 158 |

| 0.05 | 20 | 94.9 | 8222 | 59 | 70.3 | 9276 | 41 | 70.1 | 9484 | 460 | 51.7 | 35693 | 285 |

| 0.05 | 30 | 82.6 | 17284 | 110 | 71.3 | 13778 | 268 | 67.6 | 16876 | 1315 | 52.1 | 52499 | 431 |

The best results in each simulation setting are in bolface font

Table 6.

Performance of AltHap on simulated biallelic triploid data set with haplotype block length m=1000, data error rate pe=0.002, and different read lengths

| Read length | Cov | CPR | MEC | t(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 × 250 | 10 | 98.2 | 322 | 30.74 |

| 2 × 250 | 20 | 95.1 | 1986 | 59.65 |

| 2 × 250 | 30 | 98.4 | 2412 | 109.73 |

| 2 × 300 | 10 | 93.0 | 856 | 34.83 |

| 2 × 300 | 20 | 97.9 | 1410 | 66.50 |

| 2 × 300 | 30 | 97.7 | 3216 | 117.62 |

| 2 × 500 | 10 | 95.5 | 682 | 39.36 |

| 2 × 500 | 20 | 92.4 | 2605 | 66.37 |

| 2 × 500 | 30 | 93.0 | 5869 | 116.69 |

The results of tests conducted on simulated biallelic tetraploid genomes are summarized in Table 5, where we observe that AltHap outperforms the competing schemes in terms of both accuracy and running time. To investigate how the performance and complexity of AltHap vary with coverage and read length, in Table 6 we report its CPR, MEC, and runtimes obtained by simulating assembly of biallelic triploid haplotypes using paired end reads of length 2×250, 2×300, and 2×500 and coverage 10, 20 and 30 (block length is set to m=1000 and data error rate is pe=0.002). The results imply that AltHap’s runtime scales approximately linearly with both read length and coverage over the consider range of these two parameters. Additionally, as we see in Table 5, MEC score slightly increases with read length. The impact of read length in this matter is similar to that of sequencing coverage. longer sequencing reads provide more observed SNP positions and hence the MEC might increase, as also predicted by our theoretical results.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of AltHap, H-PoP, BP, and SCGD on a simulated biallelic tetraploid data set with haplotype block length m=1000. HapTree could not finish the simulations in 48 hours

| AltHap | H-PoP | BP | SCGD | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Err | Cov | CPR | MEC | t(s) | CPR | MEC | t(s) | CPR | MEC | t(s) | CPR | MEC | t(s) |

| 0.002 | 10 | 91.1 | 1113 | 43 | 70.7 | 3366 | 43 | 69.8 | 4568 | 290 | 67.1 | 14839 | 208 |

| 0.002 | 20 | 95.0 | 2113 | 87 | 73.4 | 7359 | 113 | 71.2 | 9434 | 540 | 51.7 | 41241 | 419 |

| 0.002 | 30 | 99.9 | 674 | 163 | 72.6 | 11693 | 598 | 71.5 | 12745 | 1496 | 51.8 | 61885 | 653 |

| 0.01 | 10 | 98.2 | 938 | 44 | 69.3 | 3511 | 46 | 66.4 | 6475 | 296 | 67.1 | 14819 | 213 |

| 0.01 | 20 | 99.3 | 1668 | 87 | 70.3 | 7882 | 114 | 66.9 | 10213 | 552 | 51.5 | 41712 | 414 |

| 0.01 | 30 | 95.3 | 6518 | 164 | 71.0 | 12392 | 597 | 68.4 | 13245 | 1485 | 51.5 | 61981 | 652 |

| 0.05 | 10 | 93.7 | 3905 | 44 | 67.7 | 4110 | 46 | 64.5 | 6869 | 306 | 65.0 | 15861 | 213 |

| 0.05 | 20 | 95.8 | 9645 | 89 | 69.1 | 9109 | 118 | 68.5 | 11477 | 623 | 51.9 | 41042 | 408 |

| 0.05 | 30 | 81.5 | 18690 | 165 | 70.0 | 14212 | 601 | 67.5 | 17681 | 1504 | 51.7 | 62261 | 643 |

The best results in each simulation setting are in bolface font

Simulated data: the polyallelic polyploid case

We further studied the performance of AltHap on triploid and tetraploid organisms having polyallelic sites and the results are summarized in Tables 7 and 8, respectively. Notice that none of the competing schemes are capable of handling polyallelic genomes. Evidently, AltHap is able to reconstruct underlying haplotype sequences with competitive performance at a low computational cost.

Table 7.

Performance of AltHap on simulated polyallelic triploid data set with haplotype block length m=1000. H-PoP, BP, HapTree, and SCGD cannot assemble polyallelic polyploid haplotypes

| Error rate | Cov | CPR | MEC | t(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.002 | 5 | 83.2 | 1377 | 43.05 |

| 0.002 | 10 | 93.2 | 897 | 115.13 |

| 0.002 | 15 | 93.5 | 1799 | 173.55 |

| 0.002 | 20 | 95.2 | 2346 | 232.07 |

| 0.01 | 5 | 74.7 | 2341 | 58.13 |

| 0.01 | 10 | 94.4 | 1269 | 115.41 |

| 0.01 | 15 | 90.9 | 3755 | 173.38 |

| 0.01 | 20 | 85.5 | 7272 | 235.86 |

| 0.05 | 5 | 79.9 | 3076 | 57.77 |

| 0.05 | 10 | 89.4 | 3925 | 116.33 |

| 0.05 | 15 | 93.1 | 6100 | 174.37 |

| 0.05 | 20 | 93.9 | 9120 | 236.73 |

Table 8.

Performance of AltHap on simulated polyallelic tetraploid data set with haplotype block length m=1000. H-PoP, BP, HapTree, and SCGD cannot assemble polyallelic polyploid haplotypes

| Error rate | Cov | CPR | MEC | t(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.002 | 5 | 79.4 | 2380 | 109.00 |

| 0.002 | 10 | 86.5 | 2043 | 220.6 |

| 0.002 | 15 | 93.8 | 2148 | 328.49 |

| 0.002 | 20 | 96.3 | 2388 | 432.28 |

| 0.01 | 5 | 79.7 | 2398 | 113.08 |

| 0.01 | 10 | 84.1 | 2927 | 220.33 |

| 0.01 | 15 | 82.8 | 5787 | 327.10 |

| 0.01 | 20 | 99.2 | 2319 | 432.85 |

| 0.05 | 5 | 74.6 | 4721 | 113.38 |

| 0.05 | 10 | 89.0 | 5146 | 211.43 |

| 0.05 | 15 | 92.3 | 7555 | 327.20 |

| 0.05 | 20 | 92.0 | 13704 | 435.15 |

The results of these extensive simulations imply that, as expected, haplotype assembly becomes more challenging as the number of haplotype sequences (i.e., the ploidy) increases. Nevertheless, in all the conducted studies, AltHap consistently reconstructs haplotype sequences accurately and with practically feasible computational cost. In addition, the results of Tables 4 and 5 demonstrate that the computational time of AltHap grows significantly slower with coverage than the computational time of the competing schemes. In particular, for high coverages that are characteristic of high-throughput sequencing technologies, AltHap is the most efficient among the considered algorithm.

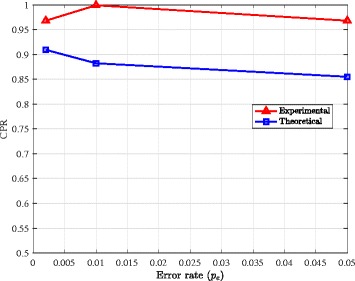

CPR lower bound

Finally, we use the results obtained by running AltHap on simulated biallelic triploid data (i.e., the results summarized in Table 4) to examine tightness of the theoretical bounds on the CPR stated in Theorem 2. In particular, theoretical bounds on CPR are compared to the CPRs empirically computed for various combinations of coverage and data error rates (averaged over 10 independent problem instances). In Fig. 3, the theoretical bound and experimental CPR results are shown as functions of the data error rate for coverage 15. We observe that the bound is reasonably close to the experimental results over the considered range of data error rates. In Fig. 4, the theoretical bound and experimental CPR results are plotted against sequencing coverage for the data error rate pe=0.002. This figure, too, implies that the theoretical CPR bound is relatively close to the experimental results. Notice that as Fig. 3 shows, the CPR score as well as the lower bound derived in Theorem 2 decrease when the sequencing error increases. On the other hand, Fig. 4 depicts that higher coverage improves AltHap’s CPR score, which again is reflected in our theoretical results.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the theoretical and experimental results. Comparison of the theoretical bound on CPR with the experimental results when Cseq=15 obtained by applying AltHap to the problem of reconstructing biallelic triploid haplotypes (synthetic data)

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the theoretical and experimental results. Comparison of the theoretical bound on CPR with the experimental results when pe=0.002 obtained by applying AltHap to the problem of reconstructing biallelic triploid haplotypes (synthetic data)

Conclusion

In this paper, we developed a novel haplotype assembly framework for both diploid and polyploid organisms that relies on sparse tensor decomposition. The proposed algorithm, referred to as AltHap, exploits structural properties of the problem to efficiently find tensor factors and thus assemble haplotypes in an iterative fashion, alternating between two computationally tractable optimization tasks. If the algorithm starts the iterations from an appropriately selected initial point, AltHap converges to a stationary point which is with high probability in close proximity of the solution that is optimal in the MEC sense. In addition, we analyzed the performance and convergence properties of AltHap and found bounds on its achievable MEC score and the correct phasing rate. AltHap, unlike the majority of existing methods for haplotype assembly for polyploids, is capable of reconstructing haplotypes with polyallelic sites, making it useful in a number of applications involving plant genomes. Our extensive tests on real and simulated data demonstrate that AltHap compares favorably to competing methods in applications to haplotype assembly of diploids, and significantly outperforms existing techniques when applied to haplotype assembly of polyploids.

As part of the future work, it is of interest to extend the sparse tensor decomposition framework to viral quasispecies reconstruction and recovery of bacterial haplotypes from metagenomic data.

Additional file

Supplement for “Sparse Tensor Decomposition for Haplotype Assembly of Diploids and Polyploids”. Additional file 1 provides details on derivation of the proposed step size, and derivation of MEC and CPR bounds. (PDF 210 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Somsubhra Barik for advice on experiments.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation under grants CCF 1320273 and CCF 1618427. The publication costs of this article was funded by the National Science Foundation under grants CCF 1320273 and CCF 1618427.

Availability of data and materials

All data are available on request. The code for AltHap is freely available from https://github.com/realabolfazl/AltHap.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Genomics Volume 19 Supplement 4, 2018: Selected original research articles from the Fourth International Workshop on Computational Network Biology: Modeling, Analysis, and Control (CNB-MAC 2017): genomics. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcgenomics.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-19-supplement-4.

Abbreviations

- BP

Belief propagation

- CPR

Correct phasing rate

- FPT

Fixed parameter tractable

- ILP

Integer linear programming

- MCMC

Markov chain Monte Carlo

- MEC

Minimum error correction

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

Authors’ contributions

Algorithms and experiments were designed by AH, BZ, and HV. Algorithm code was implemented and tested by AH and BZ. The manuscript was written by AH, BZ, and HV. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12864-018-4551-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Abolfazl Hashemi, Email: abolfazl@utexas.edu.

Banghua Zhu, Email: 13aeon.v01d@gmail.com.

Haris Vikalo, Email: hvikalo@ece.utexas.edu.

References

- 1.Schwartz R, et al. Theory and algorithms for the haplotype assembly problem. Communin Info Syst. 2010;10(1):23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark AG. The role of haplotypes in candidate gene studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2004;27(4):321–33. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibbs RA, Belmont JW, Hardenbol P, Willis TD, Yu F, et al. The international hapmap project. Nature. 2003;426(6968):789–96. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabeti PC, Reich DE, Higgins JM, Levine HZP, Richter DJ, et al. Detecting recent positive selection in the human genome from haplotype structure. Nature. 2002;419(6909):832–37. doi: 10.1038/nature01140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lancia G, Bafna V, Istrail S, Lippert R, Schwartz R. Snps problems, complexity, and algorithms, vol 1. In: European symposium on algorithms. Springer: 2001. p. 182–93.

- 6.Duitama J, Huebsch T, McEwen G, Suk E, Hoehe MR. Refhap: a reliable and fast algorithm for single individual haplotyping. In: Proceedings of the First ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics and Computational Biology. ACM: 2010. p. 160–9.

- 7.Lippert R, Schwartz R, Lancia G, Istrail S. Algorithmic strategies for the single nucleotide polymorphism haplotype assembly problem. Brief Bioinforma. 2002;3(1):23–31. doi: 10.1093/bib/3.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie M, Wu Q, Wang J, Jiang T. H-PoP and H-PoPG: Heuristic partitioning algorithms for single individual haplotyping of polyploids. Bioinformatics; 32(24):3735–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Pirola Y, Zaccaria S, Dondi R, Klau GW, Pisanti N, Bonizzoni P. Hapcol: accurate and memory-efficient haplotype assembly from long reads. Bioinformatics. 2015;32.11(2015):1610–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuleshov V. Probabilistic single-individual haplotyping. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(17):379–85. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patterson M, Marschall T, Pisanti N, Van Iersel L, Stougie L, et al. Whatshap: Weighted haplotype assembly for future-generation sequencing reads. J Comput Biol. 2015;22(6):498–509. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2014.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonizzoni P, Dondi R, Klau GW, Pirola Y, Pisanti N, Zaccaria S. On the minimum error correction problem for haplotype assembly in diploid and polyploid genomes. J Comput Biol. 2016;23(9):718–36. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2015.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cilibrasi R, Van Iersel L, Kelk S, Tromp J. On the complexity of several haplotyping problems. In: Algorithms in Bioinformatics. WABI 2005. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 3692. Springer: 2005. p. 128–39.

- 14.Wang R, Wu L, Li Z, Zhang X. Haplotype reconstruction from snp fragments by minimum error correction. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(10):2456–62. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z, Deng F, Wang L. Exact algorithms for haplotype assembly from whole-genome sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(16):1938–45. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He D, Han B, Eskin E. Hap-seq: an optimal algorithm for haplotype phasing with imputation using sequencing data. J Comput Biol. 2013;20(2):80–92. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonizzoni P, Dondi R, Klau GW, Pirola Y, Pisanti N, Zaccaria S. Annual Symposium on Combinatorial Pattern Matching. Cham: Springer; 2015. On the fixed parameter tractability and approximability of the minimum error correction problem. [Google Scholar]

- 18.He D, Choi A, Pipatsrisawat K, Darwiche A, Eskin E. Optimal algorithms for haplotype assembly from whole-genome sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(12):183–90. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy S, Sutton G, Ng PC, Feuk L, Halpern AL, et al. The diploid genome sequence of an individual human. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(10):254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bansal V, Halpern AL, Axelrod N, Bafna V. An MCMC algorithm for haplotype assembly from whole-genome sequence data. Genome Res. 2008;18(8):1336–46. doi: 10.1101/gr.077065.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JH, Waterman MS, Li LM. Diploid genome reconstruction of ciona intestinalis and comparative analysis with ciona savignyi. Genome Res. 2007;17(7):1101–10. doi: 10.1101/gr.5894107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bansal V, Bafna V. HapCUT: an efficient and accurate algorithm for the haplotype assembly problem. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(16):153–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edge P, Bafna V, Bansal V. Hapcut2: robust and accurate haplotype assembly for diverse sequencing technologies. Genome Res. 2017;27(5):801–12. doi: 10.1101/gr.213462.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aguiar D, Istrail S. Hapcompass: a fast cycle basis algorithm for accurate haplotype assembly of sequence data. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(6):577–90. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duitama J, McEwen GK, Huebsch T, Palczewski S, Schulz S, et al. Fosmid-based whole genome haplotyping of a hapmap trio child: evaluation of single individual haplotyping techniques. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;:1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Das S, Vikalo H. SDhaP: Haplotype assembly for diploids and polyploids via semi-definite programming. BMC Genomics. 2015;16.1(2015):260. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1408-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puljiz Z, Vikalo H. Decoding genetic variations: Communications-inspired haplotype assembly. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform (TCBB) 2016;13.3(2016):518–30. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2015.2462367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang W-Y, Hormozdiari F, Wang Z, He D, Pasaniuc B, Eskin E. Leveraging reads that span multiple single nucleotide polymorphisms for haplotype inference from sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(18):2245. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delaneau O, Marchini J. Integrating sequence and array data to create an improved 1000 genomes project haplotype reference panel. 2014; 5:3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Berger E, Yorukoglu D, Peng J, Berger B. Haptree: A novel bayesian framework for single individual polyplotyping using ngs data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(3):e1003502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Motazedi E, Finkers R, Maliepaard C, de Ridder D. Exploiting next-generation sequencing to solve the haplotyping puzzle in polyploids: a simulation study. Brief Bioinform. 2017. bbw126, 10.1093/bib/bbw126. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Cai C, Sanghavi S, Vikalo H. Structured low-rank matrix factorization for haplotype assembly. IEEE J Sel Top Sign Proc. 2016;10(4):647–57. doi: 10.1109/JSTSP.2016.2547860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaisson M, Mukherjee S, Kannan S, Eichler EE. International Conference on Research in Computational Molecular Biology. Cham: Springer; 2017. Resolving multicopy duplications de novo using polyploid phasing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renny-Byfield S, Wendel JF. Doubling down on genomes: polyploidy and crop plants. Am J Bot. 2014;101(10):1711–25. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1400119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prosperi MCF, Salemi M. QuRe: Software for viral quasispecies reconstruction from next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(1):132–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larsen RM. Lanczos bidiagonalization with partial reorthogonalization. DAIMI Rep Ser. 1998;27(537).

- 37.Baglama J, Reichel L. Augmented implicitly restarted lanczos bidiagonalization methods. SIAM J Scien Comput. 2005;27(1):19–42. doi: 10.1137/04060593X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deng F, Cui W, Wang L. A highly accurate heuristic algorithm for the haplotype assembly problem. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(2):2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-S2-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geraci F. A comparison of several algorithms for the single individual snp haplotyping reconstruction problem. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(18):2217–25. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Candès EJ, Recht B. Exact matrix completion via convex optimization. Found Comput Math. 2009;9(6):717–72. doi: 10.1007/s10208-009-9045-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keshavan RH, Montanari A, Oh S. Matrix completion from noisy entries. J Mach Learn Res. 2010;11(Jul):2057–78. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun R, Luo ZQ. Guaranteed matrix completion via non-convex factorization. IEEE Trans Info Theory. 2016;62(11):6535–79. doi: 10.1109/TIT.2016.2598574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gunasekar S, Acharya A, Gaur N, Ghosh J. Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases. Berlin: Springer; 2013. Noisy matrix completion using alternating minimization. [Google Scholar]

- 44.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation dna sequencing data. Nature genetics. 2011;43(5):491–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Das S, Vikalo H. Onlinecall: fast online parameter estimation and base calling for illumina’s next-generation sequencing. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(13):1677–83. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement for “Sparse Tensor Decomposition for Haplotype Assembly of Diploids and Polyploids”. Additional file 1 provides details on derivation of the proposed step size, and derivation of MEC and CPR bounds. (PDF 210 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data are available on request. The code for AltHap is freely available from https://github.com/realabolfazl/AltHap.