Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Our objective was to determine if the quality of care of diabetic patients at a Student-Run Free Clinic Project (SRFCP) meets the standard of care, is comparable with other published outcomes, and whether pertinent diabetic clinical indicators improve over time.

METHODS

The authors conducted a retrospective chart review of diabetic patients at three University of California-San Diego (UCSD) SRFCP sites from December 1, 2008 to December 1, 2009 (n=182), calculated the percentage who received recommended screening tests, percent at goal, and compared these to published outcomes using Fisher’s exact tests. Baseline measures were compared to most recent values using paired t tests.

RESULTS

The percentage of patients who received recommended screening tests (process measures) was blood pressure (BP) 100%, HbA1c 99.5%, creatinine 99.5%, LDL 93%, HDL and triglycerides 88%, microalbumin/creatinine ratio 80%, and ophthalmology exam 32%. Intermediate outcomes included: 70% of patients were at LDL goal <100, 70% had microalbumin/creatinine ratio <30, 61% of males were at HDL goal >40, 47% of females at HDL goal>50, 52% with triglycerides <150, 45% had BP <130/80, and 30% of patients had HbA1c <7. Mean HbA1c, LDL, HDL, triglycerides and blood pressure improved significantly over time.

CONCLUSIONS

Diabetic patients at UCSD SRFCP reached goals for both process measures and intermediate outcomes at rates that meet or exceed published outcomes of insured and uninsured diabetics on nearly all measures, with the exception of ophthalmology screening. Glycemic control, cholesterol levels, and blood pressure improved significantly during care at the UCSD SRFCP.

Student-Run Free Clinics (SRFCs) have entered the mainstream of medical education. Over half of American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) institutions responding to a 2005 survey reported having a SRFC.1 Recently, more than 300 participants attended the annual conference of the Society of Student-Run Free Clinics (SSRFC), a student-directed national organization dedicated to establishing best practices in these settings.2,3 According to preliminary data from the SSRFC, there are approximately 100 medical schools with a SRFC.4

However, research documenting SRFC outcomes has remained relatively sparse until recently.5 There is a call in the literature for SRFCs to document outcomes of student involvement, educational value, attitudes toward the underserved, patient demographics, scope of practice, and quality of care provided.1,5–6

Ryskna et al were first to publish SRFC patient outcomes in November 2009 in a study of 24 diabetic patients.7 SRFC patient outcome studies have subsequently been published on hypertension (n=60),8 depression (n=49),9 and preventive care (n=114).10 Each found that the SRFC provided high-quality care to the patients they serve.

This study examined clinical outcomes of diabetic patients at three University of California San Diego (UCSD) Student-Run Free Clinic Project (SRFCP)11 sites using American Diabetes Association (ADA) Clinical Practice Guidelines12 and compared outcomes to published data from insured, uninsured, local, state, and national populations to determine if we were meeting the standards of care.6,13–22

FAMILY MEDICINE

Methods

This was a retrospective medical record review. Patients over 18 years with a clinic visit from December 1, 2008, through December 1, 2009, and a diagnosis of diabetes were included in this study. We obtained study data from a student-designed Microsoft Access (Redmond, WA) clinical electronic database and online electronic laboratory records (Quest Diagnostics, Madison, NJ). Paper charts were consulted for verification when indicated.

Process performance was measured as the percentage of diabetic patients who had received pertinent exams (HbA1c, LDL, triglycerides, HDL, microalbumin/creatinine ratio, blood pressure, and ophthalmology screening) within the year prior to their last visit.

Intermediate outcomes were assessed using means and standard deviations of most recent values for pertinent laboratory studies and blood pressure readings. The percentage of patients at goal was determined by using the number of patients at goal as the numerator and the number of patients who received that test as the denominator. We compared process measures and intermediate outcomes to other published outcomes with Fisher’s exact tests using the statistical program “R” (Vienna, Austria). Paired t tests in Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA) compared baseline versus most recent values for intermediate outcomes. Independent sample t tests in Microsoft Excel compared outcomes between clinic sites. The first laboratory or blood pressure value recorded for each patient was used as the baseline value, even when the first recorded value occurred before the study period. This study was approved by the University of California Institutional Review Board, project #100543.

Results

Twenty-four percent of the UCSD SRFCP patient population (182/763) was confirmed to be diabetic and included in this study. The study population had been followed by the SRFCP clinic for a mean of 2.64 years prior to the study period (range zero to 10 years, standard deviation [SD]=2.66). The average number of visits during the study year was 5.06 (range 1–19, SD=3.45). Thirty-nine patients (21%) had their initial visit during the study,9 (4.6%) of whom had only one visit during the study period. Demographics included: mean age 53 years (range 18–80, SD=11.5); 59% female, 41% male; 75% Latino, 15% Caucasian, 4% Asian, 3% African American, 3% Other; 71% Spanish speaking, 27% English, 2% Other; and 10% homeless.

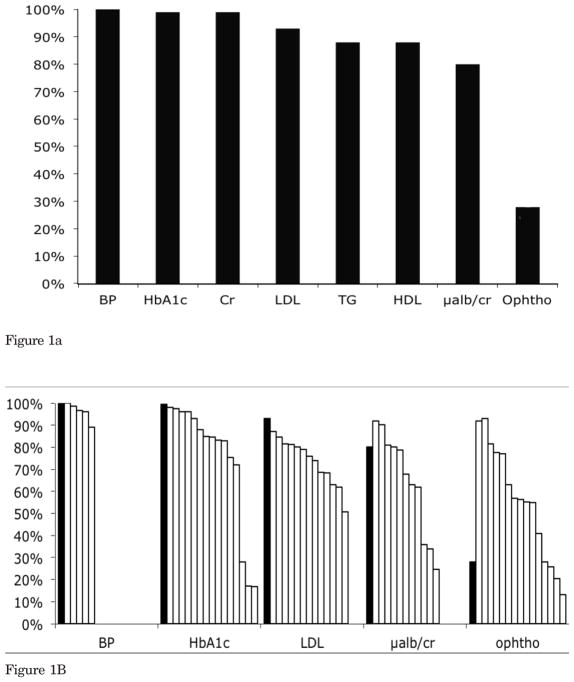

The percentage of patients who received recommended diabetic testing (process measures) was: 100% blood pressure, 99.5% HbA1c and serum creatinine, 93% LDL, 88% HDL and TG, 80% urine microalbumin/creatinine ratio, and 32% ophthalmology screening (Figure 1a). Table 1 lists means and SDs for intermediate outcomes measures and the percentage of patients who reached ADA goals.

Figure 1. Process Measures: Percentage of Diabetic Patients Receiving Recommended Testing at the UCSD SRFCP From December 1, 2008 Through December 1, 2009 (n=182).

Figure 1a—Percentage of diabetic patients receiving recommended testing at UCSD SRFCP

Figure 1B—Percentage of diabetic patients receiving recommended testing at UCSD SRFCP compared with other published outcomes13–22

USCD—University of California San Diego

SRFCP—Student-Run Free Clinic Project

Table 1.

Intermediate Outcomes for Diabetic Patients at the UCSD SRFCP December 1, 2008 to December 1, 2009, Including the Percentage Who Met ADA Treatment Goals

| Clinical Indicator | Mean (SD) | ADA Goal 2009 | % at Goal | # of Patients at Goal | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c | 8.28 (2.1) | <7.0 | 30% | 54 | 181 |

| LDL | 91 (33) | <100 | 70% | 119 | 169 |

| Triglycerides | 169 (102) | <150 | 52% | 84 | 161 |

| HDL (male patients) | 45.3 (13.9) | >40 | 61% | 37 | 61 |

| HDL (female patients) | 50.5 (12.1) | >50 | 47% | 47 | 100 |

| Urine microalbumin/creatinine | 104 (377) | <30 | 70% | 102 | 145 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 127 (19) | <130 | 58% | 106 | 182 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 76 (12) | <80 | 64% | 116 | 182 |

| Blood pressure | 127/76 | <130/<80 | 45% | 82 | 182 |

HbA1c—Hemoglobin A1c

HDL—High density lipoprotein

LDL—Low density lipoprotein

USCD—University of California San Diego

SRFCP—Student-Run Free Clinic Project

Table 2 presents the comparison of baseline versus most recent values for intermediate outcomes. HbA1c, LDL, HDL, triglycerides, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure showed significant improvements (P<.001 for all except systolic blood pressure, P<.05). No differences were seen in outcomes between sites, except that mean blood pressure was lower at the Baker Elementary school site than the Downtown site (123.4/72.4 versus 129.6/77.3 (P<.03). Clinical outcomes of diabetic patients at the UCSD SRFCP were compared to other published diabetic outcomes (Figure 1b, Tables 3 and 4).

Table 2.

Baseline Versus Most Recent Values in Diabetic Patients Seen at the UCSD SRFCP From December 1, 2008, to December 1, 2009

| Clinical Indicator | Baseline Value Mean (SD) |

Most Recent Value Mean (SD) |

n | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c | 9.15 (2.51) | 8.19 (2.15) | 157 | <.001 |

| LDL | 116.34 (43.60) | 87.21 (32.19) | 152 | <.001 |

| Triglycerides | 230.18 (191.87) | 159.64 (84.28) | 151 | <.001 |

| HDL | 46.11 (13.84) | 49.35 (13.00) | 150 | <.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 131.89 (18.20) | 126.65 (18.77) | 174 | <.05 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 81.86 (12.08) | 75.08 (11.79) | 174 | <.001 |

| Urine microalbumin/creatinine | 91.83 (210.20) | 92.66(345.97) | 118 | .980 |

| Serum creatinine | 0.83 (0.26) | 0.82 (0.27) | 160 | .35 |

HbA1c—Hemoglobin A1c

HDL—High density lipoprotein

LDL—Low density lipoprotein

USCD—University of California San Diego

SRFCP—Student-Run Free Clinic Project

Table 3.

UCSD SRFCP Diabetic Patient Outcomes From December 2008–December 2009 Compared With Published Outcomes of Diabetic Patients From Varying Practice Types, Locations, and Insurance Status

| Insurance Location | Unins. UCSD SRFCP | Insured Medicare FFS, San Diego, CA13 | Insured Medicare FFS, CA13 | Insured VA, US14 | Insured Managed Care, US14 | Insured and Unins, NHANES III US15 | Insured Managed Care, US16 | Mixed Rural NC17 | Insured Resident Clinic VA, NC18 | Mixed Resident Clinic NC18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 182 | 17,055 | 255,897 | 1,273 | 6,901 | 414 | 8,661 | 142 | 249 | 391 |

| Process measures (patients who received exams) | ||||||||||

| BP | 100% | 96%* | 89%* | 98.6%† | ||||||

| HbA1c | 99.5% | 84.6%* | 83.1%* | 93%* | 83%* | 84.8%* | 88.0%* | 96%* | 98%† | |

| LDL | 93% | 81.2%* | 80.2%* | 79%* | 63%* | 68.7%* | 68.3%* | 87%† | 74%* | |

| TG | 88% | |||||||||

| HDL | 88% | |||||||||

| μ alb/cr | 80% | 92%‡ | 81%† | 78.6%† | 62.0%* | 63%† | 36%* | |||

| Ophtho exam | 32% | 55.2%‡ | 54.9%‡ | 57%‡ | 28%† | 77.6%‡ | 20.4%* | 93%‡ | 77%‡ | |

| Intermediate outcomes (percent of patients at goal) | ||||||||||

| LDL <100 | 70% | 52%* | 36%* | 72%† | 66%† | |||||

| LDL <130 | 86% | 86%† | 72%* | 40.1%* | 87%† | 86%† | ||||

| BP <130/80 | 45% | 35.8%* | 34%* | 38%† | ||||||

| BP <140/90 | 77% | 53%* | 52%* | 59.6%* | 51.4%* | 65%* | 64%* | |||

| BP, HbA1C, and chol | 7.8% | 7.3%† | ||||||||

| HbA1c <7.0 | 30% | 37%† | ||||||||

| 7.0 to 8.0 | 29% | 26%† | ||||||||

| >8.0 | 41% | 37%† | ||||||||

| >9.0 | 30% | 20%‡ | ||||||||

| >9.5 | 24% | 8%‡ | 20%† | 37.3%* | ||||||

| >10% | 19% | 12.4%† | ||||||||

USCD—University of California San Diego SRFCP—Student-Run Free Clinic Project

UCSD SRFCP outcome is significantly better than published outcome (P<.05)

UCSD SRFCP is not statistically different than published outcome (P>.05)

UCSD SRFCP outcome is significantly worse than published outcome (P<.05)

BP—blood ressure

Chol—cholesterol

CHC—community health center

FFS—fee for service

HbA1c—hemoglobin A1c

HDL—high density lipoprotein

LDL—low density lipoprotein

μalb/cr—urine mircoalbumin/creatinine ratio

TG—triglycerides

Mixed—uninsured and insured

Unins:—uninsured

VA—Veterans Affairs

Table 4.

UCSD SRFCP Diabetic Patient Outcomes From December 2008–December 2009 Compared With Published Outcomes of Diabetic Patients From National Data Sources

| Uninsured UCSD SRFCP | Insured and Uninsured (NHANES+BRFSS)19 National Survey | Insured and Uninsured (NHANES+BRFSS)20 National Survey | Insured Medicare Managed Care National (DQIP)21 | Uninsured > 1 Year National22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process measures (percent of patients who received exams) | |||||

| Blood pressure | 100% | ||||

| HbA1C | 99.5% | 28%† | 72%† | 16.8%† | |

| LDL | 93% | 84.6%† | 62%† | ||

| TG | 88% | ||||

| HDL | 88% | 64.2%† | |||

| microalb/cr | 80% | 67.7%† | 34%† | ||

| Ophtho exam | 32% | 63% | 41% | 56.4% | |

| Intermediate outcomes (percent of patients at goal) | |||||

| LDL <100 | 70% | 11%† | 33.8%† | ||

| LDL <130 | 86% | 42%† | 30.4%† | 38%† | |

| BP <130/80 | 45% | ||||

| BP<140/90 | 77% | 65.7%† | 68.0%† | ||

| HbA1c <7.0 | 30% | 42.9% | 47% | ||

| 7.0 to 8.0 | 29% | 15.7% (7.0 to 7.9) | 21.1 (7.0 to 7.9) | ||

| >9.0 | 30% | 28.0% | 20.6% | ||

| >9.5 | 24% | 18.0% 26.9%† in uninsured |

35%%† | ||

| >10% | 19% | 14.90%† | 14.4%† | ||

USCD—University of California San Diego

SRFCP—Student-Run Free Clinic Project

BRFSS—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

DQIP—Diabetes Quality Improvement Program

HbA1c—hemoglobin A1c

HDL—high density lipoprotein

LDL—low density lipoprotein

NHANES—National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

microalb/cr—urine mircoalbumin/creatinine ratio

TG—triglycerides

UCSD SRFCP percentage is the same or better than the published outcome, without inferring statistical significance. Sample sizes (n) were not reported for these publications, therefore statistical significance in comparison with UCSD SRFCP outcomes can not be made.

Discussion

The UCSD SRFCP met or exceeded standards of care for diabetes process outcomes and intermediate outcomes in nearly all categories when compatred to other published studies. To our knowledge, this is the first publication documenting longitudinal diabetes chronic disease management outcomes at a SRFC. Our results demonstrated significant improvements in glycemic control, lipid management, and blood pressure.

This study demonstrates that challenging patient populations, including the uninsured, non-English speakers, immigrants, and homeless, can achieve control of chronic disease under the care of a SRFC. A notable exception to meeting quality standards was the rate of ophthalmology screening.

SRFCs provide a unique opportunity within the medical school curriculum to teach medical students population-based medicine, registries, chronic disease outcomes, and assessment of quality of care. Under close faculty supervision, students have their own “practice” and therefore have the opportunity to identify things that their practice is doing well and areas in need of improvement. We have added additional ophthalmology clinic sites and sessions, our students have taken a systematic approach to identifying and following all diabetic patients, scheduling their annual ophthalmology visits, making reminder calls, and addressing social barriers. The percentage of diabetic patients receiving a retina ophthalmology exam increased to 46% (108 of 235) for diabetic patients with one or more primary care visits to our general medical clinic in the previous year and 53% (103 of 194) for those with at least two visits.

Most SRFCs strive to meet two main objectives: (1) educate, empower, and inspire medical students and (2) provide outstanding, humanistic patient care to the uninsured and those who have difficulty accessing or do not qualify for care in traditional settings. Our goal was to demonstrate that care at a SRFC can be equal to or better than a traditional setting. This study adds to the body of literature demonstrating that the quality of care at a SRFC can be equal to or better than a traditional setting. We are not suggesting that patients with access to traditional care begin to seek care in a SRFC, but rather that SRFCs are capable of and must strive to achieve these standards of care and that patients going to SRFCs are not receiving sub-standard care.

Nonetheless, patients receiving care in these settings continue to face many barriers as SRFCs often have quite limited hours, long wait times, limited capacity, and difficulty accessing imaging, surgeries, and specialty care (including ophthalmology).

In part, the low ophthalmology screening rates likely reflect the many barriers that patients of SRFCs continue to face despite access to caring, enthusiastic, and dedicated student and faculty providers.

There are several limitations of the current study. This was a single institution retrospective medical record review, and prospective multi-institutional studies are needed. The relatively small sample size impacts external validity and generalizability. Additionally, the comparative data analysis may not accurately reflect similarities or differences in outcomes as each study differed in design and data analysis.

In conclusion, the UCSD SRFCP not only provides an opportunity for medical education and service-learning for its students but also provides excellent medical care to diabetic patients who otherwise lack access to medical services. While SRFCs are a very small part of the safety net for the uninsured in our country, we strive to serve our patients well, while inspiring future physicians to become leaders and continue with their passion for caring for the underserved.

Acknowledgments

Data included in this manuscript were presented as a poster at the 2011 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Annual Spring Conference in New Orleans, LA, and as part of the presentation “Measuring Outcomes at Student-Run Free Clinics: Scholarly Activity and Collaboration” at the 2012 STFM Conference on Medical Student Education in Long Beach, CA.

The authors thank the dedicated students, staff, and volunteers of the UCSD SRFCP; Carol Bloom-Whitener and Anne Crane for administrative assistance; Steve Edelman, MD, for his ongoing dedication to our diabetic patients, and William Norcross, MD, for his constructive review of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Simpson SA, Long JA. Medical student-run health clinics: important contributors to patient care and medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):352–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0073-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Session PR1: Creating and managing student-run free clinic projects. Presented at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine 2008 Predoctoral Education Conference; Portland, OR. [Accessed January 16, 2013]. www.stfm.org/pd08web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Society of Student-Run Free Clinics. July 2012 Newsletter. [Accessed January 16, 2013];Sharing ideas in sunny California: the success of the SSRFC International Conference. http://www.studentrunfreeclinics.org/images/stories/Newsletter/ssrfc_newsletter_july_20121.pdf. Published July 2012.

- 4.Ferrara A, Moscato B, Griggs R, Thomas R, Smith S. Research session. Presented at the Society of Student-Run Free Clinics Conference in conjunction with the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine 2012 Conference on Medical Student Education; Long Beach, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meah YS, Smith EL, Thomas DC. Student-run health clinic: novel arena to educate medical students on systems-based practice. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76(4):344–56. doi: 10.1002/msj.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchanan D, Witlen R. Balancing service and education: ethical management of student-run clinics. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(3):477–85. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryskna KL, Meah YS, Thomas DC. Quality of diabetes care at a student-run free clinic. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(4):969–81. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zucker J, Gillen J, Ackrivo J, Schoreder R, Keller S. Hypertension management in a Student-Run Free Clinic: meeting national standards? Acad Med. 2011;86(2):239–45. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820465e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieberman K, Meah Y, Chow A, Tornheim J, Rolon O, Thomas D. Quality of mental health care at a Student-Run Clinic: care exceeds that of publicly and privately insured populations. J Community Health. 2011;36(5):733–40. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butala NM, Murk W, Horowitz LI, Graber LK, Bridger L, Ellis P. What is the quality of preventive care provided in a student-run free clinic? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(1):414–24. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck E. The UCSD student-run free clinic project: transdisciplinary health professional education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(2):207–19. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Diabetes Association. ADA standards of medical care in diabetes 2009. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(suppl 1):S13–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lumetra. Annual A1C test rates by California county fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes, January 2006 –December 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerr EA, Gerzoff RB, Krein SL, et al. Diabetes care quality in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System and commercial managed care: The TRIAD Study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(4):272–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saydah SH, Fradkin J, Cowie CC. Poor control of risk factors for vascular disease among adults with previously diagnosed diabetes. JAMA. 2004;291(3):335–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangione CM, Gerzoff RB, Williamson DF, et al. The association between quality of care and the intensity of diabetes disease management. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(2):107–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-2-200607180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porterfield DS, Kinsinger L. Quality of care for uninsured patients with diabetes in a rural area. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(2):319–23. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powers BJ, Grambow SC, Crowley MJ, Edelman DE, Oddone EZ. Comparison of medicine resident diabetes care between Veterans Affairs and academic health care systems. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):950–5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1048-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saaddine JB, Engelgau MM, Beckles GL, Gregg EW, Thompson TJ, Narayan KM. A diabetes report card for the United States: quality of care in the 1990s. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(8):565–74. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-8-200204160-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saadine JB, Cadwell B, Gregg EW, et al. Improvements in diabetes processes of care and intermediate outcomes, United States. 1998–2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(7):465–74. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleming BB, Greenfield S, Engelgau MM, Pogach LM, Clauser SB, Parrott MA, et al. The Diabetes Quality Improvement Project: moving science into health policy to gain an edge on the diabetes epidemic. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(10):1815–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.10.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Ginsburg JA, Zaslavsky AM. Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA. 2000;284(16):2061–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]