Abstract

Background and Aims:

Anesthesia for total abdominal hysterectomies is not only concerned with relieving pain during intraoperative period but also during the postoperative period. We compared clonidine and dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to levobupivacaine for epidural analgesia with respect to onset and duration of sensory block, duration of analgesia, and adverse effects.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 80 individuals between the age of 45 and 65 years of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status Classes I and II who underwent total abdominal hysterectomies were randomly allocated into two groups, comprising 40 patients in each group. Group LC received 10 ml of 0.125% levobupivacaine and 2 μg/kg of clonidine while Group LD received 10 ml of 0.125% levobupivacaine and 1 μg/kg of dexmedetomidine through the epidural catheter. Onset of analgesia, time of peak effect, duration of analgesia, cardiorespiratory parameters, side effects, and need of rescue intravenous (IV) analgesics were observed. The data analysis was carried out with Z-test and Chi-square test.

Results:

The demographic profile and ASA physical classes were comparable between the groups. Group LD had early onset, early peak effect, prolonged duration, and stable cardiorespiratory parameters when compared with Group LC. Less number of patients (42.5%) in Group LD required IV rescue analgesics when compared to Group LC (70%) and was statistically significant. The side effects’ profile was also comparable.

Conclusion:

Dexmedetomidine is a better neuraxial adjuvant compared with clonidine for providing early onset and prolonged postoperative analgesia and stable cardiorespiratory parameters.

Keywords: Anesthesia technique, clonidine, dexmedetomidine, epidural analgesia, levobupivacaine, total abdominal hysterectomy

INTRODUCTION

Epidural administration of α2 agonists in combination with local anesthetics in low doses offers new dimensions in the management of postoperative pain.[1] Levobupivacaine, S (−) enantiomer of bupivacaine, is claimed to have safer pharmacological profile with less cardiac and neurotoxic adverse effects due to its faster protein binding rate.[2,3]

α2 selective adrenergic agonists are used primarily for the treatment of systemic hypertension. α2 adrenergic agonists such as clonidine which acts on α1 and α2 receptors and dexmedetomidine which acts on α2 receptor have both analgesic and sedative properties when used as an adjuvant in regional anesthesia.[4]

Clonidine, an imidazoline derivative, was synthesized in the early 1960s and found to produce vasoconstriction that was mediated by receptors. During clinical testing of the drug as a topical nasal decongestant, clonidine was found to cause hypotension, sedation, and bradycardia. Clonidine may be useful in selected patients receiving anesthesia because it may decrease the requirement for anesthetic and increase hemodynamic stability. Other potential benefits of clonidine and related drugs such as dexmedetomidine, a relatively selective α2 receptor agonist with sedative properties in anesthesia, include preoperative sedation and anxiolysis, drying of secretions, and analgesia.[5] Clonidine is a prototypical α2 adrenergic agonist having 200-fold selectivity for α2 over α1 adrenoreceptor.

Dexmedetomidine is an imidazole compound. It is 8 times more specific for α2 adrenergic receptors when compared to clonidine.[6] Dexmedetomidine has sedative, analgesic, and sympatholytic effects that blunt many of the cardiovascular responses seen during the perioperative period. Patients remain sedated when undisturbed but arouse readily with stimulation.[7]

The present study was conducted with the primary aim of assessing the duration of postoperative analgesia between epidural levobupivacaine 0.125% with clonidine and levobupivacaine 0.125% with dexmedetomidine for total abdominal hysterectomies. The secondary outcomes measured were the onset of analgesia, hemodynamic variables, and adverse effects in both the groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The protocol was approved by the hospital ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient. Fifty adult female patients of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status Classes I and II between the age of 45 and 65 years undergoing total abdominal hysterectomies were enrolled for the study. The patients with hematological disease, bleeding or coagulation test abnormalities, psychiatric diseases, second- or third-degree heart block, renal and hepatic insufficiency, uncontrolled diabetes and hypertension, history of drug abuse, and allergy to local anesthetics were excluded from the study.

Preanesthetic checkup and routine investigations such as complete blood count, serum creatinine, and electrocardiogram (ECG) were done. Patients were kept nil by mouth for 6 h. All patients were clinically examined in the preoperative period when the whole procedure was explained. 10 cm visual analog scale (VAS) (0, no pain and 10, worst pain imaginable) was also explained during the preoperative visit.

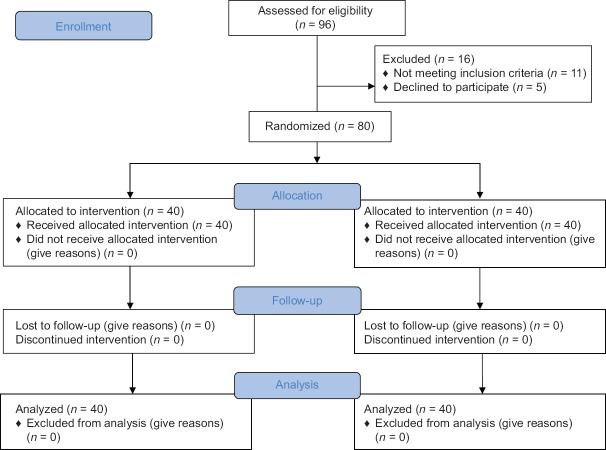

Eighty patients were randomized using a computer-generated randomization list [Figure 1]. The randomization scheme was generated using the website Randomization.com (http://www.randomization.com). Group assignment was enclosed in a sealed envelope to ensure concealment of allocation sequence. A combined spinal and epidural technique was used for anesthesia and postoperative analgesia. Patients were randomly assigned to one of the two equal groups (40 patients in each group): group LD (dexmedetomidine group) and Group LC (clonidine group).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram showing the number of patients included and analyzed

In the preoperative room, an 18-gauge intravenous (IV) line was secured, and all patients received adequate preloading with 15 mL/kg of Ringer's lactate solution over 30 min and injection ondansetron 4 mg intravenously. The patients were then shifted to the operation theater and all routine monitors, namely noninvasive blood pressure (BP), peripheral oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry (SpO2), and ECG, were attached, and after obtaining baseline vital signs, oxygen at 2 L/min was commenced through a nasal cannula.

After local infiltration with 2% lidocaine, the epidural space was identified at the L2–L3 intervertebral level with an 18-gauge Tuohy needle (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) using the loss of resistance to saline technique. No accidental dural puncture was noted in all patients. A 20-gauge epidural catheter was positioned 3 cm into the epidural space and secured in place for postoperative analgesia. Correct placement of epidural catheter was verified with a test dose of 3 ml epidural lignocaine 1.5% with adrenaline (1: 200,000). Subsequently, a 27-gauge pencil point spinal needle was advanced at L3–L4 intervertebral level through an introducer until cerebrospinal fluid was obtained, then 15 mg 0.5% heavy bupivacaine was injected and the spinal needle was withdrawn, and the patient was laid in the supine position.

Heart rate, BP, and SpO2 were recorded every minute for 15 min and every 5 min thereafter. The level of sensory (pinprick) block was assessed and recorded every minute until the start of surgery. Once the block was considered adequate (minimum block T8 – as assessed by pinprick), surgery was commenced.

After completion of surgery, the patient was shifted to recovery room. The first dose of epidural dose was given when VAS score is ≥3. All patients were randomized into two groups: Group LD received a total volume of 10 ml (levobupivacaine 0.125% with dexmedetomidine 1 μg/kg) whereas Group LC received a total volume of 10 ml (levobupivacaine 0.125% with clonidine 2 μg/kg) through epidural catheter postoperatively when the patient complains of pain (VAS ≥3).

The epidural dose of drugs given when the patient had VAS >3 after negative aspiration test and postdose vitals was recorded. Monitoring of pain (10 point VAS on which 0 indicated “no pain,” 1–3 mild pain, 4–7 moderate pain, and 8–10 severe pain), sedation by Ramsay sedation score (1 - anxious and agitated, 2 - cooperative, oriented, tranquil, 3 - asleep and responding to verbal commands, 4 - asleep but brisk response to light stimulus, 5 - sluggish response to stimulus, 6 - asleep without response to stimulation), hemodynamic parameters, respiratory rate (RR), and SpO2 were done every 10 min until 30 min and thereafter at hourly intervals for 10 h.[8] Injection diclofenac sodium 75 mg IV was given as rescue analgesia.

The onset of analgesia (time from injection of the study medication to the first reduction in pain intensity to almost complete relief) and duration of analgesia (time from epidural injection to the time of the first request for additional pain medication) were observed in both groups following epidural doses.

The incidence of hypotension (systolic BP <90 mmHg or >25% below baseline) and bradycardia (<50/min) were looked for 10 h and treated with vasopressors and atropine, respectively. Side effects that were specifically looked for were nausea, vomiting, pruritus, respiratory distress (RR <12/min), and lower extremity motor blockade.

Sample size calculation was done based on a pilot study of ten patients (5 in each group). The duration of analgesia in pilot study in two groups was 402.9 ± 48.2 min and 320.2 ± 51.4 min, respectively. To detect an observed difference of 1 h in the duration of analgesia between the groups, with a type 1 error of 5% and a power of 80%, the minimum sample size required was 37 in each group. We included forty patients in each group for better validation of results. Data were checked, entered, and analyzed using SPSS version 19 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Quantitative data were represented as mean ± standard deviation, and for qualitative data, number and percentages were used. Student's t-test was used as test of significance to find an association for quantitative data. Chi-square test was used as test of significance to find the association for qualitative data. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

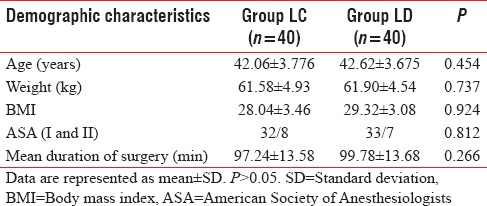

The demographic profile of the patients in both groups was comparable with regard to age, weight, and height. The distribution as per ASA class was similar and comparable in both the groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic profile

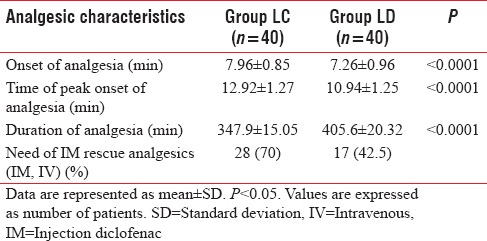

Addition of dexmedetomidine to levobupivacaine as an adjuvant resulted in an earlier onset (7.26 ± 0.96 min) of analgesia as compared to the addition of clonidine (7.96 ± 0.85 min). Dexmedetomidine not only provided early onset but also helped in achieving the peak analgesic level (VAS– 0) in a shorter period (10.94 ± 1.25 min) compared with clonidine (12.92 ± 1.27 min).

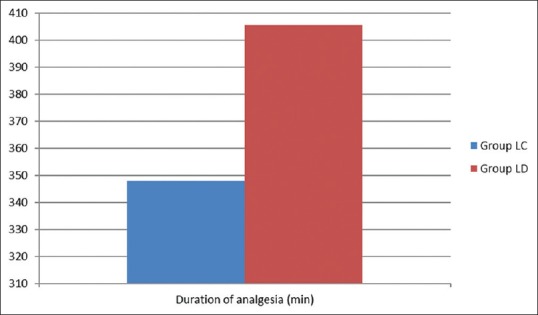

The duration of analgesia also prolonged in dexmedetomidine group (405.6 ± 20.32 min) compared to clonidine group (347.9 ± 15.05). All these analgesic characteristics were statistically significant values on comparison (P < 0.05) [Figure 2]. Less number of patients (42.5%) in Group LD required IV rescue analgesics when compared to Group LC (70%) and was statistically significant [Table 2].

Figure 2.

Duration analgesia between groups (min)

Table 2.

Comparison of analgesic characteristics in both the groups

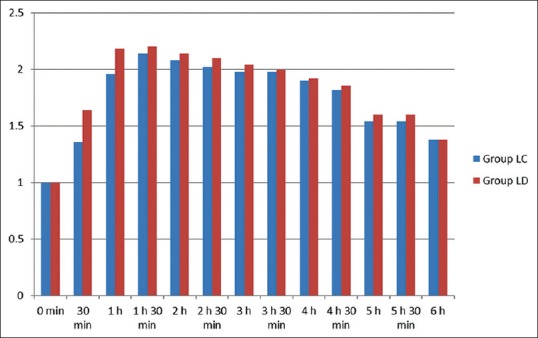

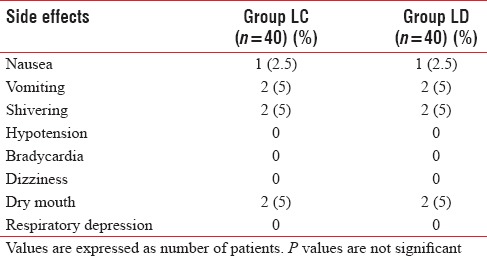

Comparative incidence of various side effects in both groups was observed in the postinjection period. The incidence of sedation was similar in both groups and also statistically nonsignificant [Figure 3]. The incidence of other side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and shivering were comparable in both groups and found to be statistically nonsignificant (P > 0.05). None of the patient showed hypotension, bradycardia, dizziness, and respiratory depression in either group [Table 3].

Figure 3.

Sedation score between two groups

Table 3.

Comparison of side effects observed in both the groups during postoperative period

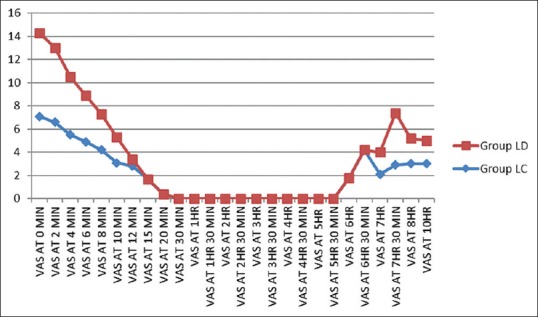

In both groups, the VAS score followed a decreasing trend from 0 to 15 min of postinjection. From 10 to 330 min (5½ h), the VAS score was stable and this period was totally pain free. After 330 min (5½ h), the VAS score showed an increasing trend. All the patients of either group asked for rescue analgesia with IV diclofenac sodium when the average VAS score was ≥3. However, the mean VAS score was higher in the clonidine group at each time interval and also the LC group needed rescue analgesia earlier than LD group [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Visual analog scale scores between groups

Only 42.5% patient in Group LD required rescue analgesic (injection diclofenac sodium) whereas 70% patients in Group LC required rescue analgesia. These differences in two groups were found statistically significant. Mean number of rescue analgesic required in Group LD was 0.7, and it was 1.8 in Group LC.

There was no significant difference of heart rate and mean arterial BP (P > 0.05) in both the groups at the time of administration of drugs, but it started to decrease as evident at 30-min postinjection, there was a fall in both groups. There was a decreasing trend of heart rate and mean arterial pressure postinjection in both groups, and this decrease was significant in the LC group compared with LD group (P < 0.05), but none of the patient showed bradycardia or hypotension at any time.

DISCUSSION

Results of this prospective, randomized, double-blinded study demonstrate that addition of 1 mg/kg body weight dexmedetomidine to 0.125% levobupivacaine produces longer duration of analgesia compared to addition of 2 μg/kg body weight of clonidine to 0.125% levobupivacaine in epidural analgesia following total abdominal hysterectomies. Addition of dexmedetomidine to levobupivacaine also hastens the onset of analgesia and increases sedation score. Fewer patients (42.5%) in Group LD required diclofenac sodium injection as rescue analgesic than patients (70%) in Group LC.

Control of postoperative pain constitutes a major problem for physicians who take care of postoperative patients. In addition, proper control of postoperative pain is very important to prevent many pulmonary, metabolic, and psychological complications.[9] Many studies have suggested that the use of postoperative epidural analgesia in high-risk patients reduces complications to a greater extent.[10]

Several studies have shown that epidural analgesia with local anesthetics combined with opioid provides better postoperative analgesia than epidural analgesia or systemic opioid alone which improves the surgical outcome.[11,12] However, the use of neuraxial opioids was associated with a few side effects, so various options including α2 agonists are being extensively evaluated as an alternative with emphasis on opioid-related side effects such as respiratory depression, nausea, urinary retention, and pruritus. The use of α2 agonists for regional neural blockade in combination with local anesthetic results in increased duration of sensory blockade with no difference in onset time.

Bupivacaine is widely used drug in epidural anesthesia, but many studies have documented the serious adverse effects of it and concern about therapy-resistant cardiovascular toxicity with bupivacaine which led to the introduction of the newer agent levobupivacaine (S-enantiomer of bupivacaine). Levobupivacaine, a long-acting enantiomerically pure (S-enantiomer) amide-type local anesthetic, exerts its pharmacological action through reversible blockade of neuronal sodium channels with a clinical profile similar to that of bupivacaine.[13] Levobupivacaine with its safe pharmacological profile, low central nervous system and cardiac toxicity, differential neuraxial blockade with preservation of motor function at low concentrations (0.125%), compatibility with α2 agonists is now becoming an important option for regional anesthesia and analgesia.

In the present study, the hypothesis is that dexmedetomidine was a better neuraxial adjuvant to levobupivacaine when compared to clonidine for providing early onset and prolonged postoperative epidural analgesia and stable cardiorespiratory parameters. According to the results obtained from the present study, this was clearly proved.

A study by Saravana Babu et al. concluded that epidural route provides acceptable analgesia in postoperative period.[14] Dexmedetomidine is a better neuraxial adjuvant to ropivacaine when compared to clonidine for providing early onset and prolonged postoperative analgesia and stable cardiorespiratory parameters. This study is in complete agreement with our study where onset of analgesia (7.26 ± 0.96 compared to 7.96 ± 0.85) was earlier in LD group. Duration of analgesia is also prolonged in LD group when compared to clonidine group (405.6 ± 20.32 vs. 347.9 ± 15.05), with stable cardiorespiratory parameters in dexmedetomidine group. Sedation was better and statistically significant in Group LD at 30 min (1.64 ± 0.48 vs. 1.36 ± 0.48) and 1 h (2.18 ± 0.38 vs. 1.96 ± 0.19) when compared to LC group.

Bajwa SJ et al. conducted a prospective and randomized study which included 50 adult female patients between age of 44 and 65 years of ASA physical Classes I and II who underwent vaginal hysterectomies.[15] Group RD received 17 ml of 0.75% epidural ropivacaine and 1.5 μg/kg of dexmedetomidine, while Group RC received admixture of 17 ml of 0.75% ropivacaine and 2 μg/kg of clonidine. They observed that addition of dexmedetomidine to ropivacaine resulted in earlier onset of sensory analgesia at T10 as compared to addition of clonidine. Sedation score of dexmedetomidine was better and statistically significant than that of clonidine; the mean time for two segment regression and motor blockade were prolonged in dexmedetomidine group. Furthermore, the time for first rescue analgesia was significantly prolonged in dexmedetomidine group when compared with the clonidine group. They concluded that dexmedetomidine is a better adjuvant than clonidine in epidural anesthesia as far as patient comfort, stable cardiorespiratory parameters, intraoperative, and postoperative analgesia are concerned.

The above study was also in complete agreement with our study where addition of dexmedetomidine to levobupivacaine resulted in earlier onset of analgesia and prolonged duration of analgesia. Sedation score was better and statistically significant in LD group at 30 min (1.64 ± 0.48 vs. 1.36 ± 0.48) and 1 h (2.18 ± 0.38 vs. 1.96 ± 0.19) when compared to LC group. In our study, dexmedetomidine is a better neuraxial adjuvant than clonidine in providing stable hemodynamic parameters with better and statistically significant sedation levels at 30 min and 1 h and prolonged postoperative analgesia 405.6 ± 20.32 vs. 347.9 ± 15.05).

Oriol-López and Maldonado-Sánchez conducted a prospective study in 40 patients who were subjected to abdominal surgery under epidural anesthesia.[16] They were given epidural dexmedetomidine at a dose of 1 μg/kg plus lidocaine and epinephrine at 3–4 mg/kg. The obtained sedation degree, according to Ramsey, at 5 min was of 3, and it was of 3–4 from 15 to 90 min, in 90% of the population. They concluded that adequate sedation (Ramsay sedation level of 3–4, P = 0.05) was maintained between 10 and 120 min with a single bolus epidural dose of dexmedetomidine. Similar to this study, we also observed that sedation was better and statistically significant in LD group at only 30 min and 1 h when compared to LC group.

The limitation of the study is the nonavailability of “combined spinal epidural kit”. Hence, we used dual segment combined spinal–epidural technique for total abdominal hysterectomies.

CONCLUSION

We conclude that dexmedetomidine 1 μg/kg is a better neuraxial adjuvant to levobupivacaine 0.125% when compared to clonidine 2 μg/kg for providing early onset and prolonged postoperative epidural analgesia with stable cardiorespiratory parameters in total abdominal hysterectomies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kamibayashi T, Maze M. Clinical uses of alpha2 -adrenergic agonists. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1345–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200011000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casati A, Baciarello M. Enantiomeric local anaesthetics: Can ropivacaine and levobupivacaine improve our practice? Curr Drug Ther. 2006;1:85–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leone S, Di Cianni S, Casati A, Fanelli G. Pharmacology, toxicology, and clinical use of new long acting local anesthetics, ropivacaine and levobupivacaine. Acta Biomed. 2008;79:92–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pichot C, Longrois D, Ghignone M, Quintin L. Dexmedetomidine and clonidine: A review of their pharmacodynamy to define their role for sedation in intensive care patients. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2012;31:876–96. doi: 10.1016/j.annfar.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farmery AD, Wilson-MacDonald J. The analgesic effect of epidural clonidine after spinal surgery: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:631–4. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818e61b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajwa S, Kulshrestha A. Dexmedetomidine: An adjuvant making large inroads into clinical practice. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:475–83. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.122044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribeiro RN, Nascimento JP. The use of dexmedetomidine in anesthesiology. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2003;53:97–113. doi: 10.1590/s0034-70942003000100013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riessen R, Pech R, Tränkle P, Blumenstock G, Haap M. Comparison of the RAMSAY score and the Richmond Agitation Sedation Score for the measurement of sedation depth. Crit Care. 2012;16:3268. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed A, Latif N, Khan R. Post-operative analgesia for major abdominal surgery and its effectiveness in a tertiary care hospital. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:472–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.119137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kehlet H. Acute pain control and accelerated postoperative surgical recovery. Surg Clin North Am. 1999;79:431–43. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70390-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Block BM, Liu SS, Rowlingson AJ, Cowan AR, Cowan JA, Jr, Wu CL, et al. Efficacy of postoperative epidural analgesia: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2003;290:2455–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moraca RJ, Sheldon DG, Thirlby RC. The role of epidural anesthesia and analgesia in surgical practice. Ann Surg. 2003;238:663–73. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094300.36689.ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bajwa SJ, Kaur J. Clinical profile of levobupivacaine in regional anesthesia: A systematic review. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:530–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.119172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saravana Babu M, Verma AK, Agarwal A, Tyagi CM, Upadhyay M, Tripathi S, et al. A comparative study in the post-operative spine surgeries: Epidural ropivacaine with dexmedetomidine and ropivacaine with clonidine for post-operative analgesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2013;57:371–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.118563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bajwa SJ, Bajwa SK, Kaur J, Singh G, Arora V, Gupta S, et al. Dexmedetomidine and clonidine in epidural anaesthesia: A comparative evaluation. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:116–21. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.79883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oriol-López SA, Maldonado-Sánchez KA. Epidural dexmedetomidine in regional anesthesia to reduce anxiety. Rev Mex Anestesiol. 2008;31:271–7. [Google Scholar]