Abstract

Introduction:

Effective postoperative analgesia is imperative for orthopedic surgeries to enhance recovery and facilitate early ambulation. Various additives have been used as adjuvants with local anesthetics in peripheral nerve blocks to provide postoperative analgesia. The aim of this study is to compare the duration of postoperative analgesia with buprenorphine and dexamethasone when administered as an adjuvant during ultrasound-guided brachial plexus blocks.

Methodology:

Sixty adult patients undergoing various upper arm surgeries were recruited for the study after acquiring ethics committee clearance. They were randomized into two groups of thirty; Group B was given ultrasound-guided supraclavicular block with 10 ml 2% lignocaine with adrenaline and 15 ml 0.5% bupivacaine and 4 mg dexamethasone as adjuvant. Group B was given the same amount of local anesthetics with 0.3 mg buprenorphine as the adjuvant. The duration of postoperative analgesia and incidence of adverse events if any were noted.

Results:

Both groups were comparable in demographics, time for onset of sensory, and motor block. The duration of postoperative analgesia was 17.4 ± 3.4 h in the buprenorphine group and 18 ± 3.49 h in the dexamethasone group. None of the patients had significant adverse effects. A single dose of buprenorphine and dexamethasone administered perineurally can provide significant postoperative analgesia for upper limb surgeries.

Keywords: Buprenorphine, dexamethasone, nerve blocks

INTRODUCTION

Effective postoperative analgesia after major orthopedic surgery is imperative to hasten recovery, early mobilization, and to improve overall patient satisfaction. Even though regional anesthesia offers excellent postoperative analgesia, the duration of a single-shot peripheral nerve block is limited. To increase the duration, a variety of adjuvants have been used in regional blocks for orthopedic surgeries, including opioids, α2 agonists, steroids, verapamil, calcium, and magnesium, and longest duration of analgesia can be achieved by clonidine, dexmedetomidine, dexamethasone, tramadol, and buprenorphine.[1] Recently, a concept of multimodal perineural analgesia has emerged which aims at prolonging postoperative analgesia by several additives and minimizing the toxic effects of individual agents in high doses.[2] The relative efficacy of these agents varies. Several studies have compared these agents against one another with respect to postoperative analgesia. Few agents that have shown consistent effect upon postoperative analgesia including buprenorphine and dexamethasone which when given in peripheral nerve blocks consistently prolongs postoperative analgesia.[3] Studies have compared both dexamethasone and buprenorphine against controls, but very few of them have compared these agents against one another with respect to analgesic efficacy. One study has compared these agents in sciatic nerve block,[4] but none in any plexus block.

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist with very high specificity for μ receptors. Opioid receptors are expressed in peripheral nerves, and buprenorphine has been shown to be effective in peripheral nerve blocks among other opioids, and perineural administration is better than systemic route.[5] Dexamethasone, a long-acting glucocorticoid, exhibits significant antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory, and antiemetic effects. It has been known for long that locally administered dexamethasone decreases nociceptive signal transmission and ectopic neuronal discharge.[6] When administered perineurally, dexamethasone prolongs the postoperative analgesia by both peripheral and central mechanisms. Both perineural dexamethasone and buprenorphine are off-label uses of the drugs; however, several studies have evaluated their use without untoward side effects. Dexamethasone has been shown to alleviate bupivacaine-induced reversible neuronal toxicity and rebound hyperalgesia.[7] Very few studies have compared these two commonly used agents head-to-head in supraclavicular blocks.

The primary objective of the study is to compare the duration of postoperative analgesia between buprenorphine and dexamethasone when used as an adjuvant in ultrasound-guided brachial plexus blocks for forearm surgeries. The secondary objective was to identify any immediate adverse events.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics committee approval was obtained, and the trial was designed in accordance with the Helsinki declaration recommendations. As both dexamethasone and buprenorphine as adjuvants to nerve blocks are not approved uses and can be termed as ‘off-label’ usage of the drugs, special mention was made in the consent and patients clearly explained about all the possible adverse events and their incidence; they were also given the option to drop out of the study at any time. Based on previous studies and a power of eighty and alpha error of 5% and minimum significant clinical difference as a 30% prolongation of analgesia duration, a sample size of sixty was determined. Accounting for drop outs, seventy consecutive patients requiring various upper limb surgeries were recruited for the study. The inclusion criteria were adult patients of age between eighteen and sixty years of American society of anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classes I and II, posted for various surgeries on the forearm. Exclusion criteria were age <18 and over 60 years, presence of comorbid illnesses that might affect peripheral nerves such as diabetes, hypertension, neurological disorders, inability to comprehend visual analog scale (VAS), allergy to study drugs and surgeries that might require iliac bone grafting. Eight patients did not satisfy the criteria. Two patients were not willing to participate and hence remaining sixty patients were allotted randomization. The concept of VAS was explained to the patient during recruitment.

The patients were randomized into two groups of thirty each by computer-generated randomization tables. All patients were premedicated with tablet diazepam 10 mg the night before and tablet ranitidine 150 mg, ondansetron 4 mg on the day of surgery. After shifting the patient inside the operating room, standard monitors (three lead electrocardiogram, pulse oximetry, noninvasive blood pressure) were applied. Injection midazolam 1 mg intravenous was given before the procedure. A scout scan was performed using a linear high frequency probe (12 Mhz, Sonoscan Turbo M5 machine) over the supraclavicular area to rule out anatomical abnormalities including aberrant vasculature. Under all aseptic precautions, ultrasound-guided supraclavicular block was performed using a high frequency (12 MHz) linear probe using an in-plane approach with a conventional 2.5 inch long needle with 25 G width. If longer needles were needed, a 23 G spinal needle was used. The corner pocket between the brachial plexus and subclavian artery was the target for needle tip placement. The drugs were prepared by an independent consultant and the person administering the block was unaware of the drug combinations.

Group B patients received 8 ml 2% lignocaine and 15 ml 0.5% bupivacaine along with 300 μg (0.3 mg) buprenorphine and Group D received the same quantity of local anesthetics with 4 mg dexamethasone. Normal saline was added to make the total volume of injectate 30 ml. All injections were prepared just before administration and all the blocks were performed by the same operator who has >5 years’ experience in ultrasound-guided blocks. The operator was blinded to the drug combinations as they were prepared by a different anesthesiologist. Patients were also blinded to the group allocation. Any pain during the procedure was planned to be treated by injection fentanyl 25 μg. If the pain was still present, general anesthesia was planned to be administered as per protocol.

The primary objective was the duration of postoperative analgesia as judged by the time taken for VAS score to reach 4 (on a scale of 0–10) in the postoperative period. The score was checked every 30 min. The time taken for the onset of sensory blockade as denoted by decreased response to pin prick as compared to the other arm and motor blockade, as indicated by the appearance of weakness on lifting the arm was noted. Any adverse events like vomiting, pruritus, persistent paresthesia and weakness were noted in the perioperative period. All the observations were made by the independent observer who was blinded to the group allocation.

Parametric data were analyzed by Student's unpaired t-test. Normalcy was determined by Shapiro–Wilk test. Categorical variables were analyzed by Chi-squared test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

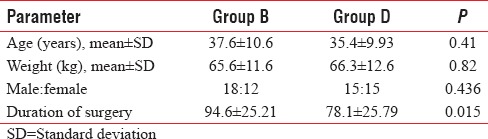

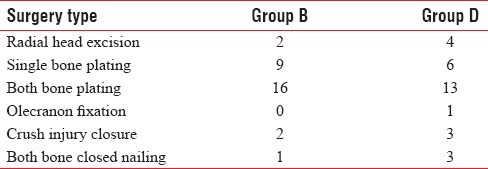

Both groups were comparable with respect to age, sex distribution, and weight [Table 1]. The type of surgeries varied from closed nailing to open reduction and plating of forearm fractures [Table 2]. All surgeries were performed in the forearm under tourniquet control. Three patients (2 from Group B and one from Group D) required intraoperative fentanyl 25 μg during the procedure. No further analgesics were needed, and none of the patients required general anesthesia.

Table 1.

Demography and surgical duration

Table 2.

Type of surgeries

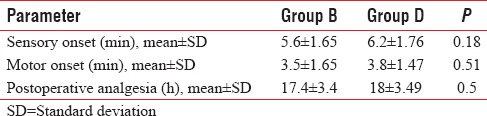

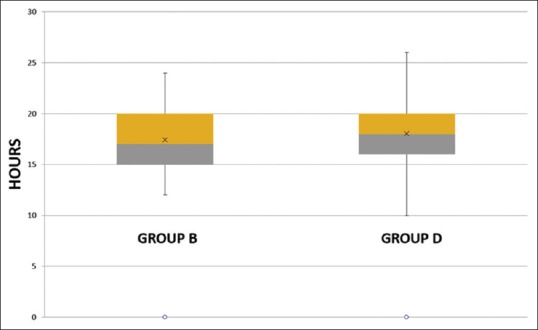

The duration of postoperative analgesia (VAS score <3) was 17.4 ± 3.4 h in the buprenorphine group and 18 ± 3.49 h in the dexamethasone group [Table 3 and Figure 1]. Student's t-test revealed P = 0.5, denoting insignificancy. The time for sensory onset and motor onset also did not differ significantly in the dexamethasone group and buprenorphine group. The time for sensory onset was 5.6 ± 1.65 min in Group B and 6.2 ± 1.76 min in Group D, and motor onset was 3.5 ± 1.65 and 3.8 ± 1.47 min in Groups B and D, respectively [Table 3]. The duration of surgery was longer in Group B as compared to Group D, which was significant (P = 0.01). Group B had more number of patients who underwent both bone forearm plating as compared to Group D (16 vs 13). The duration of these surgeries can be more than other procedures, accounting for longer mean surgery duration in the buprenorphine group (94.6 ± 25.21 vs 78.1 ± 25.79 minutes).

Table 3.

Measured parameters

Figure 1.

Duration of postoperative analgesia

None of the patients exhibited any other side effects in the study period.

DISCUSSION

Peripheral nerve blocks have gained exponential acceptance and application due to the advent of ultrasound guidance, which has shown improved onset times, higher success rates, and improved patient satisfaction. However, a main limitation is a finite duration of action and limited duration of postoperative analgesia. Indwelling catheters can provide continuous analgesia but increase complication rates and pose the risk of infection, apart from being costly and prone to dislodgement. The failure rate has been variably reported between 0.5% and 26%.[8,9] Addition of adjuvants such as opioids, steroids, α2 agonists, and magnesium can provide analgesia in the immediate postoperative period during which pain can be significant. Among the several additives analyzed, consistent results were obtained with opioids, especially buprenorphine and steroids such as dexamethasone. Dexamethasone and buprenorphine have been compared in sciatic nerve block and showed prolonged block duration, reduced the intensity of worst pain, and decreased analgesic requirements.[4]

In a recent meta-analysis, the duration of action of peripherally administered buprenorphine has been shown to prolong postoperative analgesia by 8 h (as compared to control).[5] Similarly, in a meta-analysis of dexamethasone as adjuvant in nerve block, the increase in the duration of postoperative analgesia was 5.8 h (95% confidence interval 4.8–6.8 h), as compared to control.[10] Persec et al.[11] reported a mean duration of 21 h of postoperative analgesia with 4 mg of dexamethasone with levobupivacaine in supraclavicular blocks. Our results showed a comparable duration of analgesia with buprenorphine and dexamethasone, without significant adverse effects. In a study[12] involving pediatric population, the duration of postoperative analgesia with dexamethasone was 27.1 ± 13.4 h, which was significantly longer than our values. However, all the surgeries in the study were done under general anesthesia with usual doses of opioids. Choi et al.[13] in a meta-analysis of perineural dexamethasone concluded the duration of postoperative analgesia can be up to 21 h; most of the studies analyzed employed various types of nerve blocks to provide analgesia along with a general anesthesia. The apparent slightly lesser duration of postoperative analgesia obtained in our study might be due to several reasons. In our study, brachial plexus block was administered as the sole mode of anesthesia, all surgeries employed tourniquet, and the time to reach a VAS score above 3 was considered as the end point while few studies have used a VAS score of 4. Concentration of the local anesthetic also plays an important role in the duration of action.[14] The duration of action and hence the duration of postoperative analgesia can be higher in individual nerve blocks where high concentrations can be achieved as the required volume is less, as opposed to a plexus block.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) were reported with perineural buprenorphine, but none of the patients had PONV in our trial, as all patients had received ondansetron as premedication. The time to sensory blockade and motor blockade were similar in both groups, although both these drugs have been shown to hasten the sensory and motor onset by few seconds to a minute, which might not be significant in clinical practice. Duration of motor blockade can be prolonged by approximately an hour with dexamethasone (278 in dexamethasone vs. 202 in controls).[10] However, none of the studies analyzed in the meta-analysis had duration of motor blockade as the primary objective and might not be powered to detect the same. Our study did not measure the duration and degree of motor blockade as repeated movement can cause the VAS scores to rise early. None of the patients had any motor weakness on the 1st postoperative day.

Limitations

The primary measurement scale, VAS is a subjective score and hence can vary greatly between individuals; however, the scale is widely accepted as a measure of postoperative analgesia levels. Few studies have used higher doses of dexamethasone and buprenorphine which might have shown increased duration of analgesia, but we have used two commonly used doses of these agents. Dexamethasone can cause transient increase in blood sugar levels which were not checked in our study; however, none of our patients had overt diabetes as judged by preoperative blood sugar values. The duration of surgery was significantly more in the buprenorphine group, a factor that cannot be controlled effectively. Pain intensity can be more in prolonged surgeries under tourniquet which is a confounding factor and might also have influenced the results.

CONCLUSION

A single dose of dexamethasone and buprenorphine can provide good quality postoperative analgesia lasting for several hours with minimal adverse effects. Large scale studies with different dosages and extended follow-up periods might provide further insight regarding their routine usage in daily practice.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patacsil JA, McAuliffe MS, Feyh LS, Sigmon LL. Local anesthetic adjuvants providing the longest duration of analgesia for single-injection peripheral nerve blocks in orthopedic surgery: A literature review. AANA J. 2016;84:95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams BA, Schott NJ, Mangione MP, Ibinson JW. Perineural dexamethasone and multimodal perineural analgesia: How much is too much? Anesth Analg. 2014;118:912–4. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirksey MA, Haskins SC, Cheng J, Liu SS. Local anesthetic peripheral nerve block adjuvants for prolongation of analgesia: A systematic qualitative review. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137312. e0137312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.YaDeau JT, Paroli L, Fields KG, Kahn RL, LaSala VR, Jules-Elysee KM, et al. Addition of dexamethasone and buprenorphine to bupivacaine sciatic nerve block: A randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40:321–9. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnabel A, Reichl SU, Zahn PK, Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Meyer-Frießem CH. Efficacy and safety of buprenorphine in peripheral nerve blocks: A meta analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2017;34:576–86. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson A, Hao J, Sjölund B. Local corticosteroid application blocks transmission in normal nociceptive C-fibres. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34:335–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1990.tb03097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An K, Elkassabany NM, Liu J. Dexamethasone as adjuvant to bupivacaine prolongs the duration of thermal antinociception and prevents bupivacaine-induced rebound hyperalgesia via regional mechanism in a mouse sciatic nerve block model. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurnaney H, Kraemer FW, Maxwell L, Muhly WT, Schleelein L, Ganesh A, et al. Ambulatory continuous peripheral nerve blocks in children and adolescents: A longitudinal 8-year single center study. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:621–7. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182a08fd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahsan ZS, Carvalho B, Yao J. Incidence of failure of continuous peripheral nerve catheters for postoperative analgesia in upper extremity surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:324–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huynh TM, Marret E, Bonnet F. Combination of dexamethasone and local anaesthetic solution in peripheral nerve blocks: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32:751–8. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Persec J, Persec Z, Kopljar M, Zupcic M, Sakic L, Zrinjscak IK, et al. Low-dose dexamethasone with levobupivacaine improves analgesia after supraclavicular brachial plexus blockade. Int Orthop. 2014;38:101–5. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2094-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribeiro KS, Ollapally A, Misquith J. Dexamethasone as an adjuvant to bupivacaine in supraclavicular brachial plexus block in paediatrics for post-operative analgesia. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:UC01–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/22089.8957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi S, Rodseth R, McCartney CJ. Effects of dexamethasone as a local anaesthetic adjuvant for brachial plexus block: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:427–39. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenten MG, Schoenmakers KP, Heesterbeek PJ, Scheffer GJ, Stienstra R. Effect of local anesthetic concentration, dose and volume on the duration of single-injection ultrasound-guided axillary brachial plexus block with mepivacaine: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;15:130. doi: 10.1186/s12871-015-0110-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]