Abstract

Background:

Magnesium (Mg) has been evaluated as an adjuvant to local anesthetics for prolongation of postoperative epidural and intrathecal analgesia but not with epidural levobupivacaine in lower abdominal surgeries.

Aim of the Study:

The aim of the study was to evaluate the preemptive analgesic effect of Mg added to epidural levobupivacaine anesthesia in infraumbilical abdominal surgeries.

Settings and Design:

This study design was a prospective randomized controlled trial.

Patients and Methods:

Two groups, each with fifty patients undergoing lower abdominal and pelvic surgeries with epidural anesthesia. Group M received 15 ml of a mixture of 14 ml levobupivacaine 0.5%, 0.5 ml magnesium sulfate 10% (50 mg), and 0.5 ml 0.9 NaCl at induction. Group L received 15 ml of 14 ml levobupivacaine 0.5% and 1 ml 0.9 NaCl at induction. Then, continuous infusion was used as 5 ml/h of the specific mixture of each group till the end of the surgery.

Statistical Analysis:

Chi-square test, unpaired t-test or Mann–Whitney, and Wilcoxon sign rank test were used.

Results:

No statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding intraoperative hemodynamics (P > 0.05). Sensory and motor block onset was significantly shorter in Group M (14.5 [±1.51] and 12.42 [±1.69]) compared to Group L (19.86 [±1.39] and 19.34 [±1.62]) (P = 0.001). Group M showed lower visual analog scale (VAS) pain score compared to Group L from the 2nd to the 5th h postoperatively. Time for first analgesic dose was longer in Group M (294.98 [±21.67]) compared to Group L (153.96 [±10.04]) (P = 0.001).

Conclusions:

Preoperative and intraoperative epidural Mg infusion with levobupivacaine resulted in prolonged postoperative analgesia and lower VAS.

Keywords: Epidural, levobupivacaine, lower abdominal surgeries, magnesium sulfate, pain

INTRODUCTION

Management of acute pain following surgery has been one of the major concerns in anesthetic practice. Epidural anesthesia using long-acting local anesthetics is safe, familiar, and inexpensive technique, and it provides postoperative analgesia, yet; the need of more prolonged postoperative analgesia has led to the use of different adjuvants to epidural local anesthetics.[1] Researches are still running to find the optimum adjuvant with the most satisfying analgesia and the least side effects, as the currently researched adjuvants are associated with side effects such as nausea, vomiting, respiratory depression, pruritus, and urinary retention with morphine,[2] sedation, bradycardia, and hypotension with clonidine,[3] and for epidural dexamethasone, neurological complications have not been clearly assessed in most clinical trials.[4] Levobupivacaine, the levorotatory isomers of bupivacaine, has a safer pharmacological profile with less cardiac and neurologic adverse effects.[5] Magnesium (Mg), a naturally occurring cation in the body and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, has antinociceptive effect which is mediated by control of calcium influx into the cell.[6] Very few studies examined the effect of adding magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) to epidural levobupivacaine and it was in different settings than the current study.

This randomized control study was designed to assess the effect of preoperative- plus intraoperative infusion of MgSO4 with levobupivacaine in epidural anesthesia during lower abdominal surgeries on postoperative analgesia. The primary outcome variable was the time of first rescue analgesia, and the secondary outcome variables were intraoperative hemodynamics, onset of epidural block (sensory and motor), and complications including nausea and vomiting, and postoperative visual analog scale (VAS) every 1 h for the first 5 h postoperatively.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

After approval of the hospital Ethical Committee and obtaining informed written consent from each patient, this prospective randomized study was conducted from August 2014 to the end of October 2015, on 100 patients scheduled for different infraumbilical abdominal and pelvic surgeries were enrolled in this study. Based on a pilot study, sample size was calculated according to the difference in the mean value of time to the first request of rescue analgesia between Group M (307.1 ± 16.6) and Group L (155.6 ± 7.95), with an effect size of 0.57. Assuming α =0.05, power of 80%, so a minimum sample size of 50 patients for each group was required (G Power 301 http: www.psycho.uni-duesseldorf.de).

Included patients were those aged between 20 and 60 years old and with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status Classes I and II. Exclusion criteria were patient's refusal, history of allergic reactions to local anesthetics, coagulopathy, and severe cardiac, respiratory, hepatic, or renal disease.

On arrival to the operating room, VAS was explained to the patients. A 16-gauge cannula was inserted after skin infiltration with 2% lidocaine and a preload of 500 ml intravenous (i.v.) lactated Ringer's solution was infused. Monitoring by five-lead electrocardiography, pulse oximeter, and noninvasive arterial blood pressure was done. Baseline mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), and arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) were recorded.

Epidural catheter was inserted in the sitting position at the level of L3-L4 intervertebral space, using the loss of resistance technique. Test dose of 2–3 ml lidocaine with epinephrine 1:200,000 was given after negative aspiration for blood and cerebrospinal fluid.

Patients then were randomly allocated into two groups using computerized generated random tables, and the random numbers were concealed in a closed opaque envelope:

Group M (n = 50) received 15 ml mixture of 14 ml levobupivacaine 0.5% + 0.5 ml MgSO4 10% (50 mg) + 0.5 ml of 0.9 NaCl in epidural catheter at induction then continuous epidural infusion of this mixture by 5 ml/h till the end of the surgery

Group L (n = 50) received 15 ml mixture of 14 ml levobupivacaine 0.5% + 1 ml of 0.9 NaCl in epidural catheter at induction then continuous i.v. infusion by 5 ml/h till the end of the surgery.

Time to reach sensory block at the level of T10 was assessed by loss of sensation to pinprick in the midline using a 22-gauge blunt hypodermic needle every 2 min interval until T10 dermatome was reached. Time to complete motor block was assessed using modified Bromage scale, in which block is considered (i) complete, if the patient is unable to move feet and knees, (ii) almost complete, if the patient is able to move feet only, (iii) partial, if the patient is just able to move knees, and (iv) none, if the patient has full extension of knees and feet. If the desired sensory or motor block was not achieved after 15 min from injection of the initial dose, an extra bolus dose of 5 ml of the specific mixture of each group was given through the epidural catheter. A rescue bolus of 5 ml of the specific mixture of each group was given if needed through the epidural catheter.

Failed epidural anesthesia was considered, and patient was excluded if the desired sensory level (T10) or complete motor block was not achieved 5 min after giving the extra epidural bolus which was given 15 min after the initial dose of epidural anesthesia. Then, general anesthesia was conducted by fentanyl 2 μg/kg, propofol 2 mg/kg, and 0.5 mg/kg atracurium and tracheal intubation using cuffed endotracheal tube was done. Patients were ventilated using mechanical ventilation, and ventilator parameters were adjusted to maintain normocapnia.

Adequate intraoperative fluids were maintained by lactated Ringer's solution. If MAP was decreased >20% from the baseline, a bolus of 6 mg ephedrine was given and a volume of 200 ml lactated Ringer's was infused. If HR was <50 b.p.m., a bolus of 0.6 mg atropine was given.

Intraoperatively, patients were monitored for MAP, HR, and SpO2 every 15 min. Onset of sensory and motor block and side effects including nausea, vomiting and respiratory depression were recorded.

Postoperatively, patients were monitored for the following

Pain was measured using VAS (from 0 to 10 where 0 is no pain and 10 is maximum pain) every 1 h for the first 5 h postoperatively

Time of patients’ first analgesic rescue dose defined as time from discontinuation of epidural anesthesia till the first use of rescue analgesia. A resting VAS of ≤3 was considered as a satisfactory pain relief. If patients had inadequate analgesia (i.e.,: if VAS ≥4 when measured each hour or if patient expressed intolerable pain in between VAS measurements periods) supplementary rescue analgesic was used, pethidine 1 mg/kg i/m/and paracetamol (Perfalgan®) 1 g i.v. drip.

Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median (minimum–maximum), or number (%). Comparison between categorical data (n [%]) was performed using Chi-square test. Comparison between different variables in the two groups was performed using either unpaired t-test or Mann–Whitney test whenever it was appropriate. Comparison relative to baseline (VAS 1) within the same group was performed using Wilcoxon sign rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS computer program, version 19 windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

One hundred and three patients were recruited in the study; three patients were excluded due to failure of epidural block. Type of the performed surgeries were oblique inguinal hernia (n = 38), appendicitis (n = 29), varicocele (n = 17), neurosurgical procedures (13), and rectal repair (3).

Demographic data

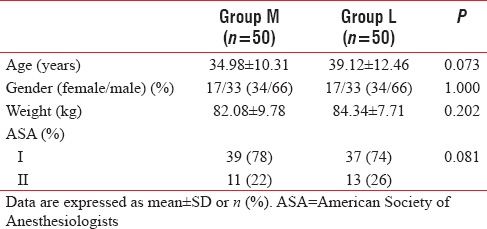

All patients were comparable regarding demographic data including age, sex, weight, and ASA classification [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data

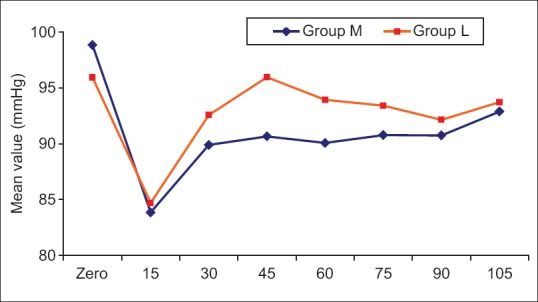

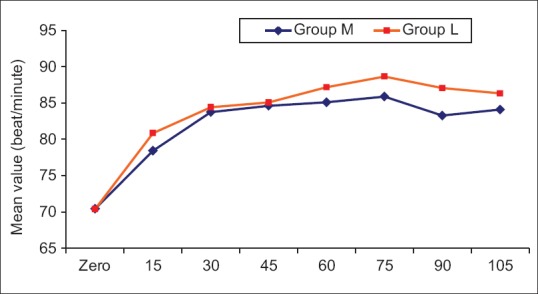

Intraoperative hemodynamics

MAP and HR were measured intraoperatively every 15 min, and they were comparable with P > 0.05 [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Mean value of arterial blood pressure in the two studied groups

Figure 2.

Mean value of heart rate in the two studied groups

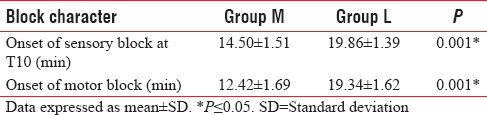

Onset of the epidural block

Onset of complete motor block was statistically shorter in the M group compared to L group (P = 0.001). Moreover, time to reach complete sensory block at level of T10 was statistically shorter in the M group compared to L group (P = 0.001) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Onset of motor and sensory block

Incidence of complications

There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression (P = 1.00). Three patients in Group M and 5 patients in Group L experienced nausea. Vomiting and respiratory depression did not occur in both groups.

Postoperative data

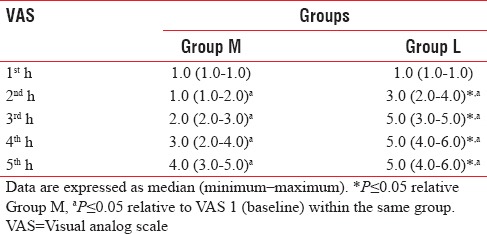

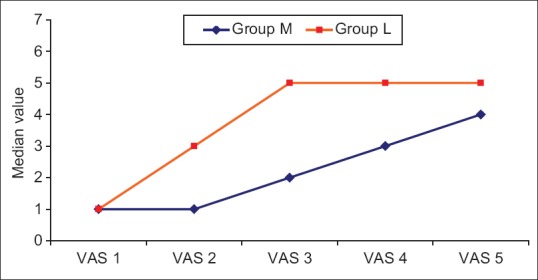

Postoperative visual analog score

There was statistically significant difference concerning VAS score between the two groups, as it was significantly lower in Group M compared to Group L in the 2nd and 3rd h postoperatively. VAS was not recorded in the study after the 3rd h in L group and after the 5th h in M group, as Ketorolac was given to alleviate pain [Table 3 and Figure 3].

Table 3.

Inter- and intragroup comparison between median values of postoperative visual analog scale in the two studied groups

Figure 3.

Median values of visual analog scale in the two studied groups

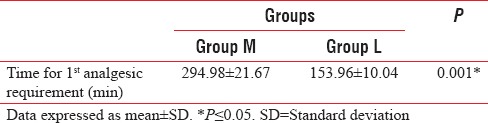

First analgesic rescue dose

The time for first dose rescue analgesic was significantly longer in the M group compared to the L group, P = 0.001 [Table 4].

Table 4.

Time for first anlgesic rescue dose (minutes)

DISCUSSION

The current study showed that preoperative adding of 50 mg MgSO4 to epidural levobupivacaine and then continuous infusion of levobupivacaine/Mg mixture till end of surgery is associated with shortening of the time to reach motor and sensory block, prolongation of both postoperative analgesia, and time for the first analgesic dose without hemodynamic implications or complications.

Regardless the route of administration whether i.v., intrathecal, or epidural, the actual site of action of Mg is probably at the spinal cord NMDA receptors. Mg is a NMDA receptor antagonist and inhibits the central sensitization from peripheral painful stimulus regulated by NMDA receptors.[7] This effect is primarily based on physiological calcium antagonism, through voltage-dependent regulation of calcium influx into the cell.[8]

In previous trials, MgSO4 was proved to be an effective adjuvant when added to bupivacaine in epidural anesthesia during different surgeries such as cesarean section and orthopedic surgeries,[9,10,11] or when added to levobupivacaine in spinal anesthesia during major orthopedic surgeries.[12] To the best of our knowledge, there are very few studies that examined the effect of adding MgSO4 to epidural levobupivacaine on postoperative analgesia. Moreover, most of the studies that evaluated the postoperative analgesic effect of epidural MgSO4 used a single dose of epidural Mg, either added preoperatively or postoperatively. However, pre- plus continuous intraoperative epidural MgSO4 infusion was examined by few studies.

Arcioni et al.[10] found that supplementation of spinal anesthesia with combined subarachnoid and epidural MgSO4 in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery significantly reduced postoperative analgesic required by the patients after major orthopedic surgeries without affecting hemodynamics.

Kandil et al.[11] studied the preemptive use of epidural MgSO4 to reduce narcotic requirements in orthopedic surgery. They found that adding magnesium to epidural bupivacaine is associated with significant improvement in VAS and significant reduction in the number of patients requesting early postoperative analgesia as well as total fentanyl consumption.

Hasanein et al.[12] studied the effect of single dose of 50 mg epidural Mg as an adjuvant to bupivacaine 0.125% and 50 μg fentanyl for labor analgesia. It was associated with faster onset, longer duration of action, and reduced the breakthrough pain with no side effects on mother and fetus assessed by Apgar score, cord blood acid-base status, and fetal HR tracings.

On sixty patients undergoing hip replacement surgeries using combined spinal–epidural anesthesia, Banwait et al.[13] studied the postoperative analgesic effect of single dose 75 mg MgSO4 added to epidural fentanyl 1 μg/kg at the end of the surgery in comparison to epidural fentanyl 1 μg/kg only. They found that it was associated with more prolonged analgesia and less rescue analgesic requirements than that found with epidural fentanyl only.

Although the results of these studies are in agreement with the current study in that epidural MgSO4 prolongs postoperative analgesia without side effects, the main differences between them and the current study are using bupivacaine in epidural anesthesia, using a single dose of epidural MgSO4 either pre- or postoperative and the type of surgeries which are different than that included in the current study which demonstrated laparotomy and visceral traction in most of the patients.

Examining the postoperative analgesic effect of epidural Mg on the same type of surgeries included in the current study was done by Gupta et al.[14] on sixty patients having total abdominal hysterectomy, but they used 0.5% bupivacaine not levobupivacaine in epidural anesthesia and a postoperative single dose of 50 mg/ml of epidural Mg with 9 ml 0.125% bupivacaine, and they conclude that Mg has provided longer duration of postoperative analgesia and reduced postoperative consumption of fentanyl without complications.

In agreement with the current study, Farouk[15] evaluated the preemptive analgesic effect of Mg when added to a multimodal patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) on ninety patients scheduled for abdominal hysterectomy under general anesthesia, who were allocated into one of three groups. (1) Pre-Mg group received a bolus of epidural Mg 50 mg before induction of anesthesia, then infusion of 10 mg/h till the end of surgery. (2) Post-Mg group received epidural saline during the same time periods and bolus epidural Mg 50 mg at the end of surgery. (3) Control group received epidural saline during all three periods. Immediately postoperatively and continued for 3 days, patients in the two Mg groups received PCEA with fentanyl 1 μg/ml, bupivacaine 0.08%, and Mg 1 mg/ml, and patients in the control group received PCEA with fentanyl 1 μg/ml and bupivacaine 0.08%. Lower pain scores and lower analgesic consumption were recorded in the pre-Mg group compared to the post-Mg and control groups, and in the post-Mg group compared to the control group, with no detected sides effects.

Kogler et al.[16] randomly allocated seventy patients undergoing thoracic surgery under general anesthesia into two groups; Group 1, 15 min before induction of general anesthesia, patients received 0.2 μg/kg sufentanil, 10 mg 0.5% levobupivacaine, and 50 mg 10% Mg through epidural catheter (Th 4-Th 6), then continuous epidural infusion of 10% Mg at a dose of 10 mg/h was started after induction. Moreover, finally, for 48 h postoperatively, patients were administered a continuous epidural infusion of sufentanil 1 μg/ml, levobupivacaine 1 mg/ml, and 10% Mg 1 mg/ml. Group 2 patients were injected at the same time periods as Group 1, with 0.2 μg/kg sufentanil and 10 mg 0.5% levobupivacaine through epidural catheter (Th 4-Th 6) preoperatively, then same volume of epidural 0.9% NaCl intraoperatively, and finally continuous epidural infusion of sufentanil 1 μg/ml and levobupivacaine 1 mg/ml for 48 h postoperatively.

In agreement with the current study, they found that the preoperative use of epidural Mg then infusion resulted in better postoperative analgesia and less analgesic consumption with a lower incidence of postoperative shivering, nausea, and vomiting. Main differences in that Kogler et al. study were different site of action, i.e., thoracic epidural, different anesthetic technique, i.e., general anesthesia, the use of two adjuvants to epidural levobupivacaine, i.e., sufentanil and MgSO4 and finally the continued postoperative use of epidural analgesia.

A recent similar study was done by Radwan et al.[17] and included 66 elderly patients undergoing lumbar discectomy and laminectomy surgery at one level under general anesthesia. Preoperatively, patients were allocated into three groups; Group A received 14 ml levobupivacaine 0.5% + 1 ml saline, Group B received 14 ml levobupivacaine 0.5% + 50 mg MgSO4, and Group C received 14 ml levobupivacaine 0.5% + 50 μg fentanyl. Then, after induction of general anesthesia, continuous epidural infusion in a rate of 5 ml/h was started as follow: Group A received levobupivacaine 0.125%, Group B received levobupivacaine 0.125% + 2 mg/ml MgSO4, and Group C received levobupivacaine 0.125% + 4 μg/ml fentanyl. Mg and fentanyl groups were comparable regarding hemodynamics. Sensory and motor block onset was significantly faster in Mg group compared to the other two groups. Mg and fentanyl groups were comparable regarding postoperative analgesia as they had a more prolonged duration of analgesia than the control group with a lower number of patients requiring either a first or a second rescue analgesic. The main differences between the current study and Radwan et al. study are the type of surgery with smaller skin incision and without visceral traction, type of population which is 65 years old and above, smaller sample size, type of anesthetic technique which is combined general and epidural anesthesia, and additional i.v. injection of 1.5 μg/kg fentanyl was used at induction of general anesthesia in all groups, and finally the use of lower concentration of levobupivacaine, 0.125%, during intraoperative epidural infusion.

Limitations and recommendations

Different in types of surgeries may lead to variations in duration of analgesia. This can be avoided in future studies by selecting patients undergoing same operative procedure. Furthermore, different doses of epidural MgSO4 should be examined in future studies.

CONCLUSIONS

We concluded that adding MgSO4 to levobupivacaine in epidural anesthesia before and during lower abdominal surgeries was associated with faster onset of action of the epidural block and an increased potency of the block, and it has a more prolonged duration of postoperative analgesia.

No significant side effects were observed during the study in the form of nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bilir A, Gulec S, Erkan A, Ozcelik A. Epidural magnesium reduces postoperative analgesic requirement. Br J Anaesth. 2007;98:519–23. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnet MP, Mignon A, Mazoit JX, Ozier Y, Marret E. Analgesic efficacy and adverse effects of epidural morphine compared to parenteral opioids after elective caesarean section: A systematic review. Esssssur J Pain. 2010;14:894.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swain A, Nag DS, Sahu S, Samaddar DP. Adjuvants to local anesthetics: Current understanding and future trends. World J Clin Cases. 2017;5:307–23. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i8.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jebaraj B, Khanna P, Baidya DK, Maitra S. Efficacy of epidural local anesthetic and dexamethasone in providing postoperative analgesia: A meta-analysis. Saudi J Anaesth. 2016;10:322–7. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.179096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajwa SS, Kaur J. Clinical profile of levobupivacaine in regional anesthesia: A systematic review. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:530–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.119172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Begon S, Pickering G, Eschalier A, Mazur A, Rayssiguier Y, Dubray C, et al. Role of spinal NMDA receptors, protein kinase C and nitric oxide synthase in the hyperalgesia induced by magnesium deficiency in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:1227–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lysakowski C, Dumont L, Czarnetzki C, Tramèr MR. Magnesium as an adjuvant to postoperative analgesia: A systematic review of randomized trials. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:1532–9. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000261250.59984.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun J, Wu X, Xu X, Jin L, Han N, Zhou R, et al. A comparison of epidural magnesium and/or morphine with bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia after cesarean section. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2012;21:310–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghatak T, Chandra G, Malik A, Singh D, Bhatia VK. Evaluation of the effect of magnesium sulphate vs. Clonidine as adjunct to epidural bupivacaine. Indian J Anaesth. 2010;54:308–13. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.68373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arcioni R, Palmisani S, Tigano S, Santorsola C, Sauli V, Romanò S, et al. Combined intrathecal and epidural magnesium sulfate supplementation of spinal anesthesia to reduce post-operative analgesic requirements: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51:482–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kandil A, Hammad RA, El Shafei MA, El Kabarity RH, Ozairy HS. Preemptive use of epidural magnesium sulphate to reduce narcotic requirements in orthopedic surgery. Egypt J Anesth. 2012;28:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasanein R, El-Sayed W, Khalil M. The value of epidural magnesium sulfate as an adjuvant to bupivacaine and fentanyl for labor analgesia. Egypt J Anaesth. 2013;29:219–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banwait S, Sharma S, Pawar M, Garg R, Sood R. Evaluation of single epidural bolus dose of magnesium as an adjuvant to epidural fentanyl for postoperative analgesia: A prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Saudi J Anaesth. 2012;6:273–8. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.101221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta A, Goyal VK, Gupta N, Mane R, Patil MN. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of addition of epidural magnesium sulphate on the duration of postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing lower abdominal surgeries under epidural anaesthesia. Sri Lankan J Anaesthesiol. 2013;21:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farouk S. Pre-incisional epidural magnesium provides pre-emptive and preventive analgesia in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:694–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kogler J, Peric M, Hrabac P, Bekavacmisak V, Karaman-Ilic M. Effects of epidural magnesium sulphate on intraoperative sufentanil and postoperative analgesic requirements in thoracic surgery patients. Signa Vitae. 2016;11:56–73. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radwan T, Awad M, Fahmy R, El Emady M, Arafa M. Evaluation of analgesia by epidural magnesium sulphate versus fentanyl as adjuvant to levobupivacaine in geriatric spine surgeries. Randomized controlled study. Egypt J Anaesth. 2017;33:357–63. [Google Scholar]