Abstract

Background:

Emergence agitation (EA) is common in pediatrics after sevoflurane anesthesia.

Aims:

We intended to study the effect of preoperative pregabalin on EA in pediatrics after sevoflurane anesthesia.

Settings and Design:

This study design was a prospective randomized controlled double-blinded study.

Patients and Methods:

Sixty children with American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status Classes I–II, aged 4–10 years, prepared for adenotonsillectomy under sevoflurane anesthesia were randomized to two equal groups (control Group C and pregabalin Group P). Children received either placebo syrup (Group C) or pregabalin syrup 1.5 mg/kg (Group P) ½ h preoperatively. We recorded postoperative EA scale (EAS) (10, 20, and 30 min postoperatively), time to open the eye, time to extubate, postanesthesia care unit (PACU) duration of stay, number of paracetamol doses (15 mg/kg) given (to control postoperative pain), and complications as vomiting and dizziness on discharge.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Independent sample t-test and Chi-square test were used as appropriate.

Results:

Pregabalin Group P showed less EAS, less analgesic (paracetamol) requirement, and less vomiting with insignificant effects on time to open the eye or extubation and PACU duration of stay compared to control group.

Conclusion:

Preoperative pregabalin decreased postoperative EAS, analgesic (paracetamol) requirement, and vomiting in pediatrics after adenotonsillectomy using sevoflurane anesthesia without affecting time to open the eye or extubation and PACU duration of stay.

Keywords: Children, emergence agitation, pregabalin, sevoflurane

INTRODUCTION

Emergence agitation (EA) is a temporary condition that occurs while awaking from general anesthesia.[1,2]

Sevoflurane is very valuable for induction and continuation of anesthesia in pediatrics, but it is correlated with increased ratio of EA.[3,4]

Medications used to prevent EA may have unwanted adverse effects such as vomiting and delayed recovery.[5]

Pregabalin belongs to gabapentinoid compounds with anticonvulsant, pain killing, and antianxiety activity.[6] The target of the existing research was to define the influence of pregabalin premedication in pediatrics on EA after sevoflurane anesthesia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The Ethical Committee of our institute approved this randomized prospective double-blinded controlled study to be executed in Tanta university hospital for 6 months (from May to October 2017) on sixty pediatric patients, prepared for adenotonsillectomy after obtaining a written and informed consent from parents and assent from children. Every parent received an explanation to the objective of the research and was afforded a secret code number to ensure privacy to participant and confidentiality of data.

Inclusion criteria included children aged 4–10 years, had American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status Class I and II, and prepared for adenotonsillectomy using sevoflurane anesthesia.

Exclusion criteria included mental or developmental retardation, allergy to the study medications, hyperactivity disorders, or use of psychiatric medications.

Patients were randomized to two groups (thirty patients each): control group (Group C) and pregabalin group (Group P). Randomization was performed using computer program to create a list of numbers. Each number (which referred to one group) was sealed in an opaque envelope. Each parent was asked to choose one envelope and give it to a person who compared the number with the computer-created list and then allocated the child to one group. The individual who assigned the patient to the group was different from the one who formulated the drugs. The anesthesiologist who gave anesthesia and collected data and the child and his parents were unaware of the child's group.

Thirty minutes before the commencement of anesthesia patients in Group C received placebo syrup (composed of sugar and saline and its taste is sweet) looked like pregabalin syrup while patients in Group P received pregabalin (trade name is Averopreg, Its concentration is100 mg/ml, manufactured by Averroes pharma, Sadat City, Egypt) 1.5 mg/kg. Both syrups were formulated by the pharmacy in equal volumes of 5 ml. After reaching the operative theater, the children were linked to monitor which included noninvasive arterial blood pressure, electrocardiogram, O2 saturation, capnography, and temperature. Then, sevoflurane 8% in 100% oxygen (through mask) was used to induce anesthesia, and venous line was inserted after induction. Then, fentanyl 1 μg/kg (Sunny pharmaceutical, Egypt) was given, intubation of the tracheal was accomplished after injecting atracurium (GlaxoSmithKline, UK) 0.5 mg/kg, and anesthesia was continued with sevoflurane.

After finishing the surgery, sevoflurane was discontinued, and the action of muscle relaxant was antagonized with neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg and atropine 0.01 mg/kg. The oropharynx was sucked, and the child was extubated after he started gaging.

After extubation, patients were sent to postanesthesia care unit (PACU), modified Alder score[7] was measured, and when the score reached ≥9, children were transmitted to ward. Emergency agitation was estimated every 10 min for 30 min postoperatively.

Postoperative pain was estimated using Faces Pain Scale-Revised (0 = no pain and 10 = very much pain)[8] at 30 min, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h postoperatively. If pain scale was ≥4, the patient was given oral paracetamol (15 mg/kg) with an interval ≥4 h.

Primary outcome included 5-point EA scale (EAS) (1 = sleeping; 2 = awake, calm; 3 = irritable, crying; 4 = inconsolable crying; 5 = intense restlessness, disorientation).[9] Secondary outcome included duration of anesthesia, time to open the eye, time to extubation, PACU duration of stay, number of paracetamol doses (15 mg/kg) given, and complications as vomiting and dizziness on discharge.

Sample size was determined using the outcomes of our pilot study which demonstrated that the mean EA score was 3.3 ± 1.3. To detect 30% reduction in EA score using the previous data and assuming α error of 0.05, β error of 0.2, and power of 80%, a sample size of 27 patients/group would be required. We intended to include thirty patients in each group (for possibly of exclusion).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was accomplished using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Quantitative data were analyzed using independent sample t-test. Chi-square test was used to analyze qualitative data. P < 0.05 was regarded to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

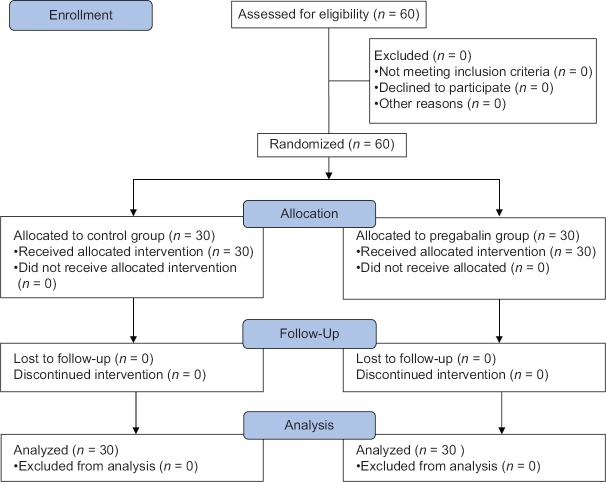

Sixty children prepared for adenotonsillectomy joined the study (30/group), and no child was excluded from the study [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram

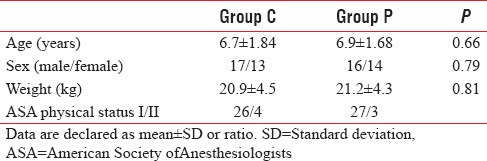

Both groups were parallel as regards patient's characters (P > 0.05) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Patient's characters

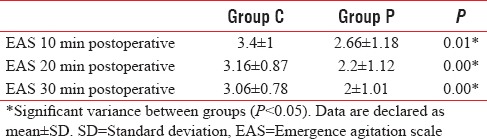

Group P showed that EAS was 2.66 ± 1.18, 2.2 ± 1.12, and 2 ± 1.01 at 10, 20, and 30 min postoperatively, while Group C showed that EAS was 3.4 ± 1, 3.16 ± 0.87, and 3.06 ± 0.78 at 10, 20, and 30 min postoperatively. Emergency agitation score (10, 20, and 30 min postoperatively) was significantly lower in Group P than Group C (P = 0.01, 0.0, and 0.0, respectively) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Postoperative emergence agitation scale

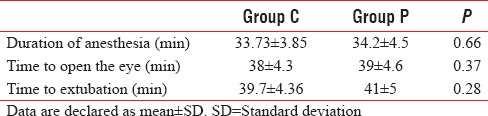

Both groups were parallel as regards duration of anesthesia (33.73 ± 3.85 min vs. 34.2 ± 4.5 min, P = 0.66), time to open the eye (38 ± 4.3 min vs. 39 ± 4.6 min, P = 0.37), and time to extubation (39.7 ± 4.36 vs. 41 ± 5 min, P = 0.28) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Operative data

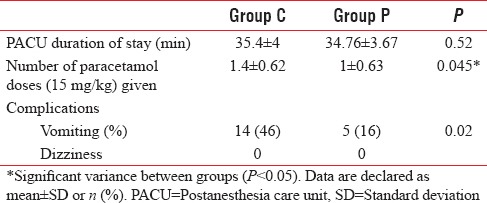

Both groups were similar as regards PACU duration of stay (35.4 ± 4 min vs. 34.76 ± 3.67 min) (P = 0.52) [Table 4]. The number of paracetamol doses (15 mg/kg) given to patients was significantly low in Group P compared to Group C (1 ± 0.63 vs. 1.4 ± 0.62, respectively) (P = 0.045). The proportion of postoperative vomiting was significantly low in Group P compared to control group (P = 0.02) [Table 4]. No patient suffered from dizziness in both groups.

Table 4.

Postoperative data

DISCUSSION

This research displayed that using pregabalin as a premedication for pediatrics undergoing adenotonsillectomy using sevoflurane anesthesia was associated with less postoperative EAS, analgesic requirement, and vomiting with insignificant effects on time to open the eye or extubation and PACU duration of stay. To our knowledge, no previous research studied the use of pregabalin to control EA in pediatrics after sevoflurane anesthesia. The precise causes of EA are not identified, but several factors may influence EA as a type of anesthetic or surgery, premedication or anesthetic adjuvants, patient age, preoperative anxiety, rapid recovery, existence of parents during recovery, and pain.[10]

The occurrence of EA is high with sevoflurane, otolaryngologic surgeries, and preschool age.[2,11,12]

Several drugs are prescribed to decrease the occurrence of EA as fentanyl, clonidine, midazolam, oxycodone, ketamine, dexmedetomidine,[13] and gabapentin.[14]

Pregabalin is a synthetic analog to the inhibitory transmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid. It has anticonvulsant, pain killing, antianxiety, and sleep-modulating effects. It binds with α2–δ subunit of presynaptic calcium channels in the nervous system and decreases the emission of several transmitters (such as serotonin, dopamine, glutamate, noradrenaline, and substance P).[15]

Pregabalin was used safely for children with partial epileptic seizure not responding to treatment and also to control pain in children receiving chemotherapy.[16,17]

Our study showed that EAS was significantly lower in pregabalin group as compared with control group. In agreement with our results, Salman et al.[14] used gabapentin (which belong to the same group of pregabalin) as premedication for pediatrics undergoing tonsillectomy and adenotonsillectomy using sevoflurane and reported that gabapentin group was associated with lower EAS and less painkiller requirement during postoperative period as compared with control group while time to eye opening or time to extubate were alike in the two groups. Furthermore, in line with our results, Azemati et al.[18] studied the effect of preoperative gabapentin on EA in females undergoing breast cancer surgery and reported that gabapentin group showed decreased EA and postoperative pain without complication as compared to control group.

Aslı Donmez et al.[19] agreed with our results as they concluded that gabapentin reduced EAS at 10 min after circumcision using sevoflurane in pediatrics, but they disagreed with our result regarding pain as they demonstrated that gabapentin had no effect on pain score.

Pesonen et al.[20] used pregabalin (150 mg preoperatively then 75 mg twice/day for 5 days postoperatively) in patients underwent cardiac surgery and concluded that pregabalin minimized postoperative opioid need and confusion in day 1 after surgery while time to extubation increased compared to placebo.

Rai et al.[21] analyzed 12 studies which assess the impact of pregabalin and gabapentin on pain after breast cancer and concluded that both drugs decreased pain and opioid consumption after surgery.

Feng et al.[22] analyzed 18 research articles and reported that preoperative pregabalin was linked with less pain, opioid consumption, and nausea and vomiting (postoperative nausea and vomiting [PONV]) after surgery but its effects varied with its dose and type of surgery.

Mathiesen et al.[23] reported that preoperative pregabalin (combined with paracetamol and placebo) and preoperative pregabalin in combination with dexamethasone and paracetamol decreased pain and analgesic (ketobemidone) requirement after tonsillectomy, these results were in line with our results. However, in contrast with our results when Mathiesen et al.[24] used the same combination in females undergoing hysterectomy, they reported that pregabalin (combined with paracetamol or paracetamol and dexamethasone) did not lower pain score and opioid consumption.

Peng et al.[25] reported that pregabalin (50 and 75 mg) produced better analgesia (over placebo) for 1½ h after laparoscopic cholecystectomy with no changes in opioid consumption, side effects, or quality of recovery.

In line with our result, Grant et al.[26] analyzed results from 23 clinical trials and reported that pregabalin (when given before surgery) was correlated with less PONV.

In contrast to our results, White et al.[27] reported that pregabalin (75–300 mg preoperatively) increased perioperative sedation but did not improve preoperative anxiety, postoperative pain, or the recovery process after minor surgery.

Furthermore, in contrast to our results, Chang et al.[28] reported that pregabalin had no effect on pain score (shoulder pain), time to first analgesia request, and analgesic consumption after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Paech et al.[29] also disagreed with our results as they reported that pregabalin (100 mg) did not decrease pain or improve recovery after gynecological surgery.

CONCLUSION

Preoperative pregabalin was associated with less postoperative EAS, analgesic requirement, and vomiting in pediatrics undergoing adenotonsillectomy using sevoflurane anesthesia without effect on time to open the eye or extubation and PACU duration of stay.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Soliman R, Alshehri A. Effect of dexmedetomidine on emergence agitation in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy under sevoflurane anesthesia: A randomized controlled study. Egypt J Anaesth. 2015;31:283–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S, Tait AR. A prospective cohort study of emergence agitation in the pediatric postanesthesia care unit. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1625–30. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000062522.21048.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JH. Mechanism of emergence agitation induced by sevoflurane anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2011;60:73–4. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2011.60.2.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uezono S, Goto T, Terui K, Ichinose F, Ishguro Y, Nakata Y, et al. Emergence agitation after sevoflurane versus propofol in pediatric patients. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:563–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200009000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahmani S, Stany I, Brasher C, Lejeune C, Bruneau B, Wood C, et al. Pharmacological prevention of sevoflurane- and desflurane-related emergence agitation in children: A meta-analysis of published studies. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:216–23. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Menachem E. Pregabalin pharmacology and its relevance to clinical practice. Epilepsia. 2004;45(Suppl 6):13–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.455003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aldrete JA. The post-anesthesia recovery score revisited. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7:89–91. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(94)00001-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. The faces pain scale-revised: Toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93:173–83. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole JW, Murray DJ, McAllister JD, Hirshberg GE. Emergence behaviour in children: Defining the incidence of excitement and agitation following anaesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2002;12:442–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.00868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aouad MT, Nasr VG. Emergence agitation in children: An update. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2005;18:614–9. doi: 10.1097/01.aco.0000188420.84763.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aono J, Ueda W, Mamiya K, Takimoto E, Manabe M. Greater incidence of delirium during recovery from sevoflurane anesthesia in preschool boys. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1298–300. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199712000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welborn LG, Hannallah RS, Norden JM, Ruttimann UE, Callan CM. Comparison of emergence and recovery characteristics of sevoflurane, desflurane, and halothane in pediatric ambulatory patients. Anesth Analg. 1996;83:917–20. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199611000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vlajkovic GP, Sindjelic RP. Emergence delirium in children: Many questions, few answers. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:84–91. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000250914.91881.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salman AE, Camkıran A, Oguz S, Donmez A. Gabapentin premedication for postoperative analgesia and emergence agitation after sevoflurane anesthesia in pediatric patients. Agri. 2013;25:163–8. doi: 10.5505/agri.2013.98852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gajraj NM. Pregabalin: Its pharmacology and use in pain management. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:1805–15. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000287643.13410.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann D, Liu J, Chew ML, Bockbrader H, Alvey CW, Zegarac E, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of pregabalin in children with refractory partial seizures: A phase 1, randomized controlled study. Epilepsia. 2014;55:1934–43. doi: 10.1111/epi.12830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vondracek P, Oslejskova H, Kepak T, Mazanek P, Sterba J, Rysava M, et al. Efficacy of pregabalin in neuropathic pain in paediatric oncological patients. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2009;13:332–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azemati S, Dokouhaki AG, Talei A, Khademi S, Moin-Vaziri N. Evaluation of the effect of preoperative single dose of gabapentin on emergence agitation in patients undergoing breast cancer surgery. Middle East J Cancer. 2013;4:145–51. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aslı Donmez A, Salman E, Sulemanji D, Alıc Y, Otkun I. The effect of gabapentin premedication on the emergence delirium in pediatric patients undergoing circumcision under sevoflurane anesthesia. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2012;40:64–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pesonen A, Suojaranta-Ylinen R, Hammarén E, Kontinen VK, Raivio P, Tarkkila P, et al. Pregabalin has an opioid-sparing effect in elderly patients after cardiac surgery: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:873–81. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rai AS, Khan JS, Dhaliwal J, Busse JW, Choi S, Devereaux PJ, et al. Preoperative pregabalin or gabapentin for acute and chronic postoperative pain among patients undergoing breast cancer surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:1317–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2017.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng D, Wei J, Luo J, Chen YY, Zhu MY, Zhang Y, et al. Preoperative single dose of pregabalin alleviates postoperative pain. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016:665–80. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathiesen O, Jørgensen DG, Hilsted KL, Trolle W, Stjernholm P, Christiansen H, et al. Pregabalin and dexamethasone improves post-operative pain treatment after tonsillectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55:297–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathiesen O, Rasmussen ML, Dierking G, Lech K, Hilsted KL, Fomsgaard JS, et al. Pregabalin and dexamethasone in combination with paracetamol for postoperative pain control after abdominal hysterectomy. A randomized clinical trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:227–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng PW, Li C, Farcas E, Haley A, Wong W, Bender J, et al. Use of low-dose pregabalin in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:155–61. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant MC, Lee H, Page AJ, Hobson D, Wick E, Wu CL, et al. The effect of preoperative gabapentin on postoperative nausea and vomiting: A Meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2016;122:976–85. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White PF, Tufanogullari B, Taylor J, Klein K. The effect of pregabalin on preoperative anxiety and sedation levels: A dose-ranging study. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1140–5. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818d40ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang SH, Lee HW, Kim HK, Kim SH, Kim DK. An evaluation of perioperative pregabalin for prevention and attenuation of postoperative shoulder pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1284–6. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181b4874d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paech MJ, Goy R, Chua S, Scott K, Christmas T, Doherty DA, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of preoperative oral pregabalin for postoperative pain relief after minor gynecological surgery. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:1449–53. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000286227.13306.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]