Abstract

Background and Aims:

This study compared if perianal block using ropivacaine and dexmedetomidine was as good as spinal anesthesia (SA) using bupivacaine (heavy) for closed hemorrhoidectomies.

Methods:

A prospective randomized study was conducted in sixty patients who underwent closed hemorrhoidectomy. Thirty patients of Group A received SA. Thirty patients in Group B received local perianal block. Patients were evaluated for onset of the block, total pain-free period, and time to ambulation. Patient satisfaction in terms of pain during injection and satisfaction with the anesthesia technique was assessed after 2-week telephonically. Data were statistically analyzed using unpaired t-test for the continuous variables and Fischer's exact test for categorical variables.

Results:

Onset of anesthesia was significantly earlier in Group B, mean (standard deviation [SD]) value being 3.17 (1.28) min as compared to Group A, 6.24 (4.28) min (P = 0.0004). Total pain-free period (mean [SD]) in minute was longer in Group B, 287 (120) min as compared to Group A, 128 (38) min. Time to ambulation was significantly earlier in Group B, 22.83 (29.32) min as compared to Group A 302 (92.41) min. Pain during injection between the two groups was comparable. However, more patients in Group B (60%) were satisfied with the anesthesia technique as compared to Group A (27.5%).

Conclusion:

Perianal block for hemorrhoidectomy with ropivacaine 0.2% using dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant is an effective and reliable technique which is as effective as SA. It provides prolonged postoperative analgesia and early ambulation.

Keywords: Anesthesia; spinal, bupivacaine, dexmedetomidine, hemorrhoidectomy, local anesthetics, pain; postoperative, ropivacaine

INTRODUCTION

Hemorrhoidectomy is one of the routine surgeries performed in our surgical theaters. Among the various techniques for hemorrhoidectomy, closed hemorrhoidectomy is the preferred and the most common procedure done. Almost all types of anesthetic techniques have been used for this surgery from general anesthesia (GA) to spinal anesthesia (SA) to local infiltration blocks or a combination of the above.[1,2,3,4]

The aim of a successful anesthetic technique for closed hemorroidectomy is to have a deep and lasting analgesia of the anal canal, a blood-free operative field, no side effects on the bladder, suppression of the vagal reflex and patient acceptability and comfort.

Today, this surgery is mostly carried out as a day care procedure. In this scenario, GA and SA have limitations in that patients can have postoperative nausea and vomiting or retention of urine leading to delay in discharge.

A lot of studies in recent times have talked of the feasibility of perianal block as the sole anesthetic for hemorrhoidectomies.[5] However, it is still not widely accepted by patients maybe due to pain on injection.[6] There is also hesitation on the part of the surgeons regarding the adequacy of relaxation under the block.

We conducted a study to compare if perianal block using ropivacaine with dexmedetomidine was as good as SA using bupivacaine for closed hemorrhoidectomy. The primary outcomes we assessed were onset of anesthesia and total pain-free period. Secondary outcomes assessed were operative ease, time to ambulation, and patient satisfaction.

METHODS

All the patients who presented to the operation theater of our hospital for elective closed hemorrhoidectomy between December 1, 2016, and July 31, 2017, were considered for the study based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The first 60 selected patients were included in the study after taking permission from the Hospital Ethics Committee. A pilot study conducted in ten patients in each group reflected the mean (standard deviation [SD]) pain-free period in the SA group as 150 (75) min, whereas it was 300 (150) min in the perianal block group. Sample size calculation for the difference of means was applied and sample size of ten was calculated for each group with an alpha error of 5% and keeping the power of the study at 80%. However, we decided on thirty individuals in each group to cater for the dropouts. Allocation concealment was done using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes, which were opened only after the participant was enrolled in the study. Block randomization with random block size was performed using random allocation software (http://random-allocation-software.software.informer.com/2.0 ).

The purpose and entire anesthetic procedure was explained in detail to all the patients and written informed consent was obtained from them.

Inclusion criteria included patients of either sex with age between 18 and 65 years, body weight of 50 kg and above and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I and II listed for elective hemorroidectomy. The exclusion criteria included patients with chronic backache, spinal deformities, history of prolapsed intervertebral disc, patients with a known history of allergy to the drugs used in the study, patients with cardiac disease, and lack of patient's consent for either technique.

All patients underwent routine preanesthetic evaluation and were given tablet alprazolam 0.25 mg orally night before surgery. They were kept fasting for fluids and solids at least 8 h prior to performing the block. The patients were randomly divided into two groups of 30 each. On arrival in the operation theater, heart rate (HR), noninvasive blood pressure, and oxygen saturation (SpO2), electrocardiography monitors were applied, and the baseline values were noted. Intravenously (i.v.) access was secured and an appropriate i.v. fluid was started. We did not want to use any preprocedural sedation in the SA group because it is not standard practice. To maintain comparability between the groups, we did not use any sedation in the perianal group. Furthermore, in our pilot study, most patients tolerated the needle pricks of perianal block under eutectic mixture of local anesthetic (EMLA).

Group A, patients were administered SA in sitting position. Patient's back was cleaned and draped followed by the identification of L3/L4 space or alternatively L2/L3 space by anatomical landmark. Skin and subcutaneous tissue were infiltrated with 2 ml of 2% plain lignocaine using a 25 mm needle. A, 25G Quincke spinal needle was then inserted into the L3/L4 space. Once free flow of cerebrospinal fluid was confirmed, 1.5 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine (heavy) was administered and the patient was immediately made supine.

For all Group B patients an EMLA, 2.5% lignocaine and 2.5% prilocaine were applied around the perianal region an hour before surgery in the preoperative holding area. Post-EMLA application Group B patients received perianal block with 40 ml of 0.2% ropivacaine with dexmedetomidine 0.5 μg/kg.

Technique of perianal block

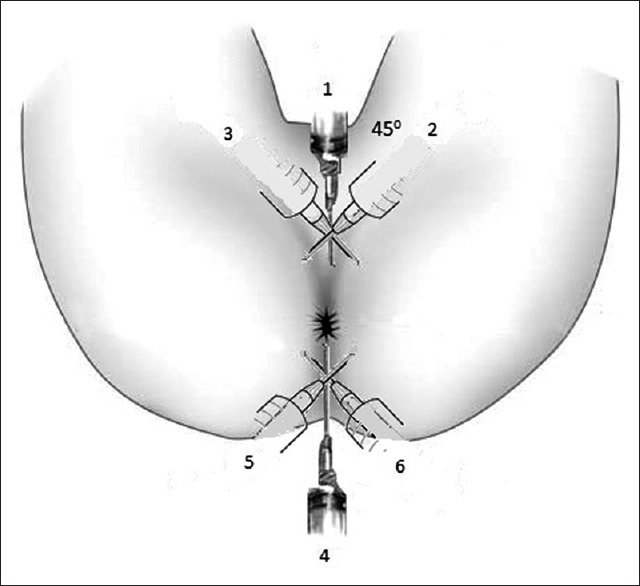

This technique used by us is a modification of the eight injection technique used by Nyström et al. in their study.[4] Patients in the perianal group were put in the lithotomy position with a sandbag underneath their buttocks to enhance the view of the perianal region. Both the buttocks were strapped laterally to the thigh with the help of Elastoplast. The perianal region was cleaned and draped. For the block, 0.2% ropivacaine with 0.5 μg/kg dexmedetomidine was mixed making the total volume of 40 ml. The mixture was injected immediately peripheral to the external sphincter in the ischiorectal fat, starting behind the anus. A 10 ml syringe with the needle (1.5 inch 21G) was advanced approximately at around 1.8–2.4 cm from the skin where the levator muscle is normally encountered. The needle was further advanced a little more, and the drug was deposited. A total of 6 “columns” of 5 ml each was injected perisphincteric in the pattern shown in Figure 1, and the remaining 10 ml was infiltrated subcutaneously around the anus, the point of penetration was from the initial anterior and posterior entry points by making the needle curved. These blocked all terminal nerve endings of the sphincters and anus without the need to target a specific nerve structure.

Figure 1.

Injection technique for local perianal block with the directions and order of the injections with the patient in lithotomy position

The onset of anesthesia was defined as loss of sensation over the perianal skin with dilatation of the sphincter and this time was noted. The surgeon was allowed to start surgery after assessing sphincter relaxation. Operative ease which was defined as no pain at two finger dilatation was recorded by the surgeon on the Scale of 3: Scale 1 – fully relaxed, Scale 2 – incompletely relaxed, and Scale 3 – not relaxed. If the operative ease was assessed by the scale as 3 or if the patient complained of discomfort or pain it was considered as a failure of block and GA was administered. Intraoperative rescue analgesia if required was given with injection tramadol 2 mg/kg slow i.v. and recorded.

Perioperative monitoring included HR, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), SpO2. They were first recorded immediately after giving the block, and this was noted as time 0. Thereafter, it was recorded at every 5 min interval for the first 15 min and then at the interval of 10 min until the end of surgery. Total operative time was recorded in both groups.

Postoperative pain was monitored every hour for first 4 h, then every two hourly for the next 4 h and then four hourly until 24 h. The pain was assessed objectively by numeric rating score (NRS). It uses a scale of 10 cm with markings 1 cm apart, the leftmost end labeled as “0” denoting no pain while the rightmost end with “10” marking denoting worst imaginable pain. The patient was asked to rate his pain on this scale and once the NRS was >4 rescue analgesia was given.

Total pain-free period was calculated as the period from the administration of the block till the patients required rescue analgesia. Postoperatively, rescue analgesia was given with injection diclofenac sodium 75 mg intramuscularly and/or injection paracetamol 1 g i.v. infusion.

Time to ambulation was defined as the time when the patient could go to the toilet unaided and it was noted down.

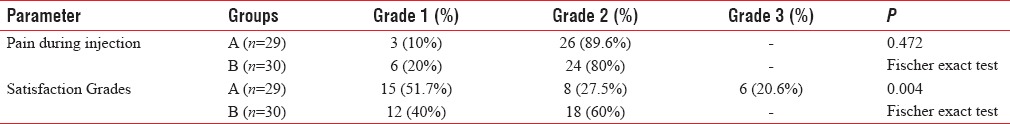

Complications such as hematoma, bleeding, urinary retention, nausea, vomiting, or any systemic side effects were looked for and recorded and compared between the two groups. Patients were contacted telephonically 2 weeks after the surgery. They were asked to rate the pain during injection while giving perianal block or SA and it was recorded as Grade 1 – No complaints of pain, Grade 2 – complained of pain but bearable and Grade 3 – unbearable pain at injection. The second question asked was satisfaction with the anesthesia technique and this was recorded as Grade 1 – very satisfied, Grade 2 – satisfied, and Grade 3 – unsatisfied.

Data were statistically analyzed using unpaired t-test for the continuous variables and Fischer's exact test for categorical variables. Analysis performed utilizing Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, USA) software and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

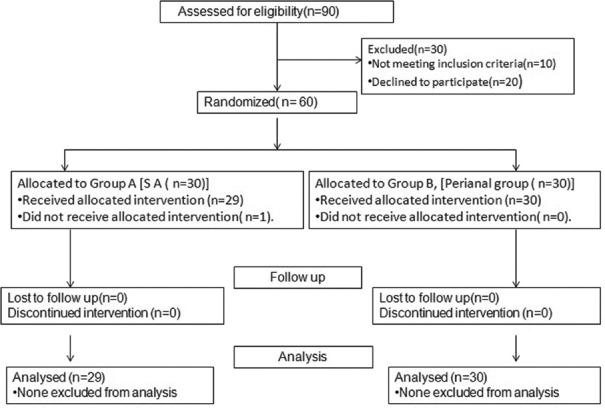

A total of 60 patients were enrolled and were allotted into two groups; Group A (SA, n = 30), Group B (Perianal, n = 30). We had one case of inadequate SA which required GA in Group A which was excluded from the result calculation [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Consort flow chart

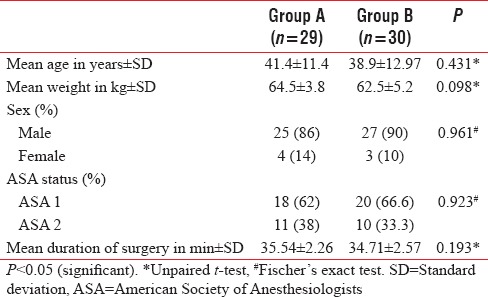

No differences were observed among the two groups in terms of age, sex, ASA classifications, and mean duration of surgery [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

Monitoring parameters HR and MAP were comparable in both groups. The mean HR (SD) lowest and the highest value in Group A varied between 72.01 (6.6) and 98.16 (2.23) per minute and in Group B varied between 71.40 (5.5) and 97.14 (2.21) per minute. Mean of MAP (SD) lowest and the highest value in Group A was between 86.73 (2.63) and 97.59 (2.12) mmHg. Mean of MAP (SD) in Group B was between 85.52 (2.46) and 97.23 (1.54) mmHg.

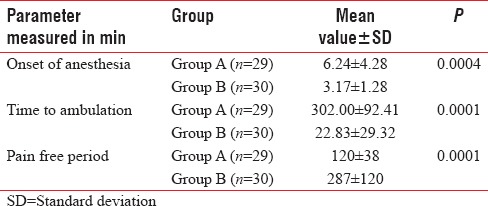

The onset of anesthesia in mean (SD) was earlier in Group B 3.17 (1.28) min as compared to Group A, 6.24 (4.28) min with P = 0.0004 [Table 2]. Patients in Group B had early ambulation at 22.83 (29.32) min as compared to Group A 302 (92.41) min with P = 0.0001 [Table 2]. When total pain-free period mean (SD) was compared in both the groups, Group B had significantly longer pain-free time with 287 (120) min when compared to Group A 120 (38) min. The P = 0.0001 [Table 2].

Table 2.

Outcome parameters

Surgical satisfaction in terms of operative ease was comparable in both groups with 96.6% patients in Group A achieving full relaxation of the anal sphincter as compared to Group B (100%) with P = 0.999. Intraoperatively, only one patient in Group A and two patients in Group B required injection tramadol 100 mg slow i.v.

About 13% of patients in Group B required rescue analgesia with injection diclofenac sodium within 24 h. Whereas, all patients in Group A required injection diclofenac sodium, and in addition, 51% of patients also required additional injection paracetamol 1 g i.v.

Two weeks later, patients were telephonically asked about the grades of pain during injection and satisfaction toward anesthesia techniques. Grades of pain during administration of injection between the two groups were comparable. About 90% of patients in Group A and 80% of patients in Group B had Grade 2 bearable pain [Table 3]. Overall satisfaction grades with anesthetic technique were higher in Group B patients in comparison to Group A with P = 0.004 [Table 3].

Table 3.

Patient's satisfaction

DISCUSSION

Haimorrhoid from the Greek word haimorrhoides meaning bleeding veins is one of the most common presentations in any surgical outpatient department. Their operative management can vary from closed hemorrhoidectomy, open hemorrhoidectomy, and rubber band ligation to staple hemorrhoidectomy. Closed hemorrhoidectomy considered the preferred choice of surgery. Any anesthetic technique for closed hemorrhoidectomy should result in early ambulation and have minimal postoperative pain. Anesthesia for closed hemorrhoidectomy can vary from GA, SA, to various kinds of local blocks in the perianal area or a combination of these three.[1,2,3,4] To be effective, any local infiltrative block must block the deep nerves namely inferior hemorrhoidal nerves, posterior branch of internal pudendal nerves and anococcygeal nerves and also the superficial branches from the inferior gluteal nerves and the perineal branches from the minor nerves from the sacral plexus.[4,7] The onset is quick (2–3 min) and is seen as relaxation of the sphincter, which is rendered painless to dilatation.[4,8] Failure to accomplish this is generally due to a superficial injection in the posterior aspect. Both the anal canal and the perianal skin are anesthetized. There have been studies which have compared perianal blocks with SA or GA.[9,10] They have all mentioned that local perianal block is feasible for hemorrhoidectomy with adequate postoperative pain relief, however, pain associated with injection is a major limiting factor preventing the use of perianal block as a sole anesthetic technique.[6]

In our study, the aim was to assess whether perianal block is as good for closed hemorrhoidectomy as SA.

We compared onset of anesthesia, total pain-free period, surgical satisfaction, patient satisfaction, and time to ambulation.

Majority of the patients in both the groups were males 86% (Group A) and 90% (Group B), respectively. Average duration of the surgery was comparable in both groups ranging between 30 and 40 min.

Looking at the hemodynamic changes, both groups did not show any bradycardia and hypotension. The reason could be because we used only 1.5 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine for SA which limited its spread and resulted in less autonomic disturbances. The dose of dexmedetomidine used in the perianal block was 0.5 μg/kg which even after systemic absorption is too low to cause significant bradycardia and hypotension.[11] Ropivacaine being a vasoconstrictor helps in further decreasing systemic absorption of any adjuvant.[12]

The onset of anesthesia was significantly earlier in Group B (3.17 ± 1.28 min) versus Group A (6.24 ± 4.28 min) P = 0.0004 [Table 2]. The total pain-free period (mean ± SD) was greatly prolonged in Group B (287 ± 120 min) in comparison to Group A (120 ± 38 min) [Table 2]. Bharathi et al. in their study of perianal block noted that the mean duration of analgesia lasted approximately 5 h. This could be because they used only 30 ml of 0.25% of bupivacaine with 1% lignocaine and adrenaline solution.[8] It is possible that inclusion of dexmedetomidine with ropivacaine prolonged the duration of analgesia in our study. Local perianal block with ropivacaine by Nystrom et al. in their study had postoperative analgesia extending up to 12 h.[4] The literature provides enough evidence that analgesia with ropivacaine lasts longer.[13,14]

Intraoperatively, one patient in Group A needed injection tramadol and two patients in Group B. Standard rescue analgesia protocol was followed postoperatively where it was observed that only 13% patients in Group B required nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) whereas, 100% patients in Group A required NSAIDs indicating longer lasting analgesia in Group B.

In the perianal group, there were no complications. However, two patients (6.6%) of hemorrhoidectomy under SA developed urinary retention. Anannamcharoen et al. in their study also found higher incidence of urinary retention in SA (30.3%) than those in the LA group (8.8%).[9] In Group B, no patient had urinary retention which could be explained by the younger age profile of our study group. Similar findings were recorded by Bharathi et al. in their study titled evidence-based switch to perianal block for perianal surgeries.[8] No other complications were noted in either groups in our study.

Patient satisfaction was assessed after 2 weeks of follow-up telephonically using the questionnaire which included the grades of pain during injection and the satisfaction grades with the anesthetic technique. Pain during injection around the sensitive perianal area had been reported by many,[1,2] but Arndt et al. reported that the speed of injection also plays a significant role.[15] Scarfone et al. suggested that the slower rate of injection causes minimal pain.[16] In our study, we included both, local application of EMLA cream 60 min before the procedure as done in the studies of Ho et al.[17] and Wahlgren and Quiding[18] and slower rate of LA injection which translated to improved patient satisfaction scores in Group B patients. On enquiry, 20% of patients in Group B experienced no pain with 80% having bearable pain which was comparable to Group A and majority of the patients in Group B were satisfied with the anesthesia technique [Table 3].

The high patient satisfaction and acceptability with the perianal technique is related to the early ambulation, longer postoperative pain relief, and lesser pain during the injection with the absence of side effects such as nausea or urinary retention.

There are few limitations in our study. Complete blinding could not be performed because two different anesthesia techniques were utilized. Blinding of the patient as well as anesthesiologist for the technique could not be performed. However, the data collector for this study was blinded to the techniques used. Enquiring telephonically 2 weeks postprocedure about the patient satisfaction and pain on injection could have resulted in a recall bias.

Perianal block being a novel technique with early onset of the block, prolonged postoperative analgesia, and early ambulation of the patient contribute to the strengths of this study.

Future research directions for larger sample population for all subsets of perianal surgeries will be required to establish the efficacy and safety of perianal blocks.

CONCLUSION

We conclude that perianal block using ropivacaine 0.2% with dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant is as effective, reliable, and safe as SA for closed hemorrhoidectomy. In addition to providing long-lasting postoperative analgesia, it also is acceptable to the surgeon. The application of local anesthetic cream EMLA before giving the block probably resulted in the minimal pain on injection.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aphinives P. Perianal block for ambulatory hemorrhoidectomy, an easy technique for general surgeon. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92:195–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kushwaha R, Hutchings W, Davies C, Rao NG. Randomized clinical trial comparing day-care open haemorrhoidectomy under local versus general anaesthesia. Br J Surg. 2008;95:555–63. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delikoukos S, Zacharoulis D, Hatzitheofilou C. Local posterior perianal block for proctologic surgery. Int Surg. 2006;91:348–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nyström PO, Derwinger K, Gerjy R. Local perianal block for anal surgery. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8:23–6. doi: 10.1007/s10151-004-0046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gabrielli F, Cioffi U, Chiarelli M, Guttadauro A, De Simone M. Hemorrhoidectomy with posterior perineal block: Experience with 400 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:809–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02238019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park SJ, Choi SII, Lee SH, Lee KY. Local perianal block in anal surgery: The disadvantage of pain during injection despite high patient satisfaction. J Korean Surg Soc. 2010;78:106–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gudaityte J, Marchertiene I, Pavalkis D. Anesthesia for ambulatory anorectal surgery. Medicina (Kaunas) 2004;40:101–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bharathi RS, Sharma V, Dabas AK, Chakladar A. Evidence based switch to perianal block for ano-rectal surgeries. Int J Surg. 2010;8:29–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anannamcharoen S, Cheeranont P, Boonya-usadon C. Local perianal nerve block versus spinal block for closed hemorrhoidectomy: A ramdomized controlled trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91:1862–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerjy R, Lindhoff-Larson A, Sjödahl R, Nyström PO. Randomized clinical trial of stapled haemorrhoidopexy performed under local perianal block versus general anaesthesia. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1344–51. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aantaa R, Scheinin M. Alpha 2-adrenergic agents in anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1993;37:433–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1993.tb03743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cederholm I, Evers H, Löfström JB. Skin blood flow after intradermal injection of ropivacaine in various concentrations with and without epinephrine evaluated by laser Doppler flowmetry. Reg Anesth. 1992;17:322–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asik I, Kocum AI, Goktug A, Turhan KS, Alkis N. Comparison of ropivacaine 0.2% and 0.25% with lidocaine 0.5% for intravenous regional anesthesia. J Clin Anesth. 2009;21:401–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanai A, Osawa S, Suzuki A, Ozawa A, Okamoto H, Hoka S, et al. Regression of sensory and motor blockade, and analgesia during continuous epidural infusion of ropivacaine and fentanyl in comparison with other local anesthetics. Pain Med. 2007;8:546–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arndt KA, Burton C, Noe JM. Minimizing the pain of local anesthesia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;72:676–9. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198311000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scarfone RJ, Jasani M, Gracely EJ. Pain of local anesthetics: Rate of administration and buffering. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:36–40. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho KS, Eu KW, Heath SM. Randomized controlled trial of hemorrhoidectomy under mixture of local anesthesia versus general anesthesia. Br J Surg. 2000;87:410–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wahlgren CF, Quiding H. Depth of cutaneous analgesia after application of a eutectic mixture of the local anesthetics lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA cream) J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:584–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]