Abstract

A series of a rigid meso-meso directly-linked chlorin-chlorin, chlorin-bacteriochlorin, and bacteriochlorin-bacteriochlorin dyads, including free bases as well as Zn(II), Pd(II) and Cu(II) complexes has been synthesized, and their absorption, emission, singlet oxygen (1O2) photosensitization, and electronic properties have been examined. Marked bathochromic shift of the long-wavelength Qy absorption band and increase in fluorescence quantum yields in dyads, compared to the corresponding monomers, are observed. Non-symmetrical dyads (except bacteriochlorin-bacteriochlorin) show two distinctive Qy bands, corresponding to the absorption of each dyad component. A nearly quantitative S1-S1 energy transfer between hydroporphyrins in dyads, leading to an almost exclusive emission of hydroporphyrin with a lower S1 energy, have been determined. Several symmetrical and all non-symmetrical dyads exhibit a significant reduction of fluorescence quantum yields in solvents of high dielectric constants; this is attributed to the photoinduced electron transfer. The complexation of one macrocycle by Cu(II) or Pd(II) enhances intersystem crossing in the adjacent, free base dyad component, which is manifested by a significant reduction in fluorescence and increase in quantum yield of 1O2 photosensitization.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Arrays of tetrapyrrolic macrocycles directly connected between their meso positions represent an interesting class of molecules, since due to orthogonal arrangement of macrocycles there is a little direct π-conjugation between dyad components, however due to their close proximity, there is a substantial through-space electronic interaction between chromophores, which significantly affects electronic, optical, and electrochemical properties of the resulting constructs.1–14 Meso-meso linked porphyrin,1–9 chlorin,10–12 bacteriochlorin,12 and corrole13,14 dyads have been reported, and their spectral and electronic properties, as well as energy- and electron transfer processes between array components have been examined. Resulting dyads have been applied, for example, as biomimetic models for photosynthetic light harvesting2–4 and electron transfer arrays,5 fluorescence imaging agents,6 molecular wires,1,7 molecules for information storage,8 and triplet state photosensitizers.9,12

The vast majority of such arrays reported so far are composed of porphyrins, while arrays of hydroporphyrins have been explored far less.10–12 Hydroporphyrins - chlorins and bacteriochlorins, are partially saturated tetrapyrrolic macrocycles that differ substantially from fully unsaturated porphyrins, in terms of electronic, optical, and electrochemical properties.15–18 In particular, hydroporphyrins exhibit enhanced absorption in the red (chlorins) or near-IR (bacteriochlorins) spectral window, and they exhibit intense fluorescence in the respective regions.16–18 Thus, they are more efficient in photon harvesting in visible and near-IR spectral windows, which is utilized by natural light harvesting antenna.15 Moreover, due to their near-IR absorption and emission, hydroporphyrins are used for a host of photomedical applications, such as photodynamic therapy and in vivo imaging.19–22 Hydroporphyrins are easier to oxidize than porphyrins,23 and are therefore more prone to the oxidative photoinduced electron transfer (PET), which is utilized in natural photosynthetic reaction centers, where hydroporphyrins function as primary electron donors.15 Thus, it can be expected that hydroporphyrin dyads will exhibit set of properties, distinctive from those observed in analogous porphyrin arrays. For example, we recently reported a series of symmetrical meso-meso directly-linked12 and strongly conjugated24,25 hydroporphyrin dyads. For the meso-meso directly linked bacteriochlorin dyad, fluorescence quantum yield Φf and lifetime τf, as well as singlet oxygen 1O2 quantum yield ΦΔ are all progressively reduced when solvent dielectric constant (ε) increases, resulting in nearly complete quenching of fluorescence and 1O2 photosensitization in solvents of high ε.12 These quenching of photochemical activity in bacteriochlorin dyad is much more extensive than in corresponding chlorin12 and porphyrin dyads.26 Although details of excited state dynamics for these dyads are still being investigated, these observations indicate that directly linked hydroprorphyrin arrays have a complex and rich photochemical properties. This has prompted us to examine the broader set of directly-linked hydroporphyrin arrays, which includes various symmetrical metal complexes, and non-symmetrical arrays i.e. arrays composed of two hydroporphyrins with distinctive electronic, optical, and redox properties. To the best of our knowledge, the only non-symmetrical directly-linked hydroporphyrin dyads have been reported only recently by Borbas et al.11 (non-symmetrical meso-β directly linked porphyrin-chlorin dyad were also reported27).

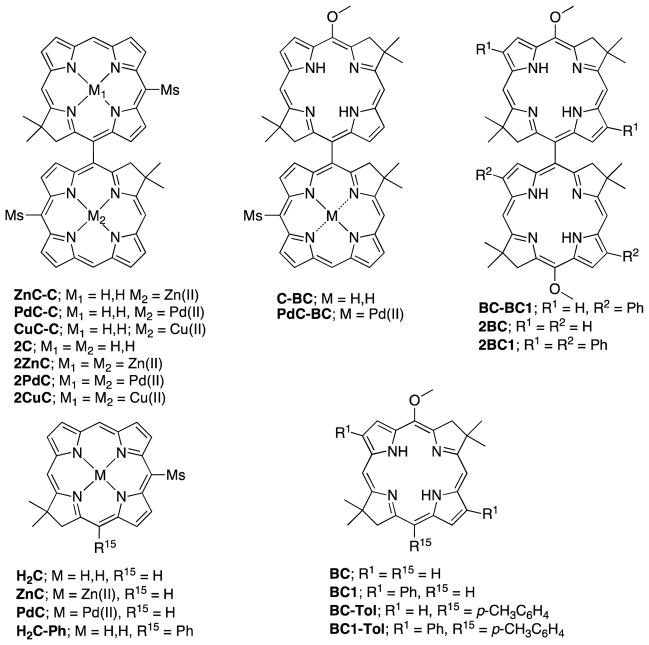

Here, we report the synthesis and characterization of a series of symmetrical and non-symmetrical chlorin-chlorin, chlorin-bacteriochlorin, and bacteriochlorin-bacteriochlorin dyads (Chart 1). Symmetrical dyads include free base chlorin-chlorin 2C12 as well as bacteriochlorin-bacteriochlorin 2BC12 and 2BC1, and chlorin-chlorin metal chelates: 2ZnC,12 2PdC, 2CuC, (note, that 2C and 2BC have been previously reported, and they are included here for comparison). Non-symmetrical chlorin-chlorin dyads are composed of one free base and one metal [Zn(II), Pd(II), or Cu(II)] complex of the same chlorin (ZnC-C, PdC-C, and Cu-C respectively). Asymmetry here is achieved by metalation of one chlorin component. It is well known that metalation significantly alters spectral, electronic and redox properties of hydroporphyrins.28,29 Chlorin-bacteriochlorin dyads include one composed of two-free base macrocycles (C-BC) and that composed of a Pd(II) complex of the same chlorin (PdC-BC). Finally, bacteriochorin-bacteriochlorin dyad BC-BC1 is composed of two bacteriochlorin free-bases with different sets of substituents on the macrocycle perimeter. As benchmarks we included monomers ZnC,28,30 PdC, H2C,28,30 H2C-Ph,31 BC,18 BC1, BC-Tol,12 and BC1-Tol.

Chart 1.

Structures of dyads and monomers discussed in this paper (Ms = 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl).

This set of compounds has enabled us to determine several key aspects of photophysics of directly linked hydroporphyrin dyads. First, we sought to determine how metalation and electronic asymmetry between dyads components affects the basic absorption and emission properties of dyads, and how efficient energy transfer is between dyads’ components. Second, we determined to what extent emission properties in dyads are influenced by the solvent dielectric constant, in view of the possible PET between redox non-equivalent hydropoprhyrin components. Finally, we intended to determine how heavy element complexation [i.e. Pd(II) or Cu(II)] by one hydroporphyri in dyad affects fluorescence and singlet oxygen (1O2) photosensitization of the adjacent, free base hydroporphyrin. Tetrapyrrolic macrocycles are capable of photosensitizing 1O2 (as well as other reactive oxygen species) due to the high quantum yield of intersystem crossing (ISC).32 Complexation of a heavy element, particularly Pd(II) or Pt(II), greatly increases ISC rate and quantum yield, and consequently quantum yield of ROS photosensitization.32 However, insertion of Pd(II) and Pt(II) into chlorins causes substantial hypsochromic shift of the Qy band, placing it out of the “therapeutic window” and thus rendering them potentially less efficient for deep tissue PDT33–35 (note however, that complexation of bacteriochlorins with Pd(II) causes a bathochromic shift of the Qy band29). In addition, metal complexation alters redox properties of the tetrapyrrolic macrocycles, which affects the efficiency of ROS photosensitization.36 Moreover, for Pd(II) and Pt(II) complexes of hydroporphyrins reduction of the T1 lifetime (to < 10 μs) is observed,29,36 which makes these chelates less useful for applications where long T1 lifetime (i.e. hundreds of microseconds) is desirable. Alternative strategies to enhance ISC in tetrapyrrolic macrocycles without complexation of heavy element by central nitrogen atoms include T1-T1 energy transfer,37–43 enhancement of ISC through interaction with an unpaired electron of a metal44,45 or stable organic radical,46 and the “remote” heavy atom effect.47,48 In principle, these strategies allo ISC rate and T1 lifetime in tetrapyrrolic macrocycles to be tuned without undesirable alteration of optical and redox properties. We have therefore determined here whether heavy metal complexation of one hydroporphyrin improve 1O2 photosensitization (as an indirect measure of T1 formation) of the free base hydroporphyrin in dyads.

Experimental Section

Known compounds ZnC,30 H2C,30 2C,12 2ZnC,12 BC-B,12 BC-Tol,12 2BC,12 and C-Br,31 were synthesized following the reported procedures. Pyrrole S349 was previously synthesized, and here it was prepared essentially followed reported procedure. Pyrrole S450 was also reported, and here was prepared by a different procedure.

General procedure for palladium catalyzed reactions

Schlenk flask was charged with all reagents and solvent was added. The resulting mixture was degassed by freeze-thaw cycles (two times), and filled with nitrogen. A palladium catalyst was added to the reaction flask, and the mixture was degassed again by freeze-thaw cycles (two times), and filled with nitrogen. Reaction flask was warmed to the room temperature and placed in the pre-heated oil bath (85 °C). TLC, UV-Vis spectroscopy, and LD-MS were used to monitor the progress of the reaction. When consumption of the hydroporphyrin starting material was determined, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, diluted with ethyl acetate, washed (water and brine), dried (Na2SO4), and concentrated. The final purification was done by column chromatography, as specified below.

C-BC

Samples of BC-B (19.7 mg, 0.037 mmol), C-Br (20.1 mg, 0.037 mmol), Cs2CO3 (121.7 mg, 0.37 mmol) and Pd(PPh3) 4 (12.8 mg, 0.011 mmol) in toluene/DMF (12 mL, 2:1), were reacted overnight as described in General procedure. Column chromatography (silica, hexanes/DCM 1:1) afforded a green brown solid sample; 11.4 mg, 36% 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −1.88 (s, 1H), −1.70 (s, 1H), −1.39 (s, 2H), 1.72 (s, 3H), 1.76 (s, 3H), 1.83 (s, 3H), 1.84 (s, 3H), 1.92 (s, 3H), 1.94 (s, 3H), 2.06 (s, 6H), 2.55 (s, 3H), 3.61 (d, J = 17.3 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (d, J = 17.3 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (d, J = 17.3 Hz, 1H), 3.85 (d, J = 17.3 Hz, 1H), 4.53 (s, 2H), 4.58 (s, 3H), 7.20 (s, 2H), 7.74 (dd, J = 1.8, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.38 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.55 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 2H), 8.77–8.80 (m, 3H), 8.96 (s, 1H), 8.98 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 9.01 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 9.05 (dd, J = 1.9,4.4 Hz, 1H), 9.29 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 9.87 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 21.5, 21.6, 30.8, 31.3, 31.6, 31.8, 45.4, 46.0, 46.1, 47.8, 52.3, 52.6, 65.5, 94.8, 97.3, 97.9, 106.8, 111.1, 112.6, 118.0, 121.2, 121.3, 122.9, 123.4, 123.8, 127.1, 127.8, 128.2, 131.6, 131.9, 132.8, 134.6, 135.1, 135.4, 136.1, 136.4, 137.6, 138.3, 139.2, 139.3, 141.0, 142.1, 152.0, 152.6, 153.9, 161.9, 165.1, 169.0, 169.2, 175.2; MS ([M]+, M = C56H56N8O): Calcd: 856.4572, Obsd: (HRMS, ESI) 856.4539.

PdC-BC

A solution of C-BC (5.0 mg, 5.3 μmol) and Pd(OAc) 2 (7.9 mg, 0.035 mmol) was stirred in chloroform/MeOH (6 ml of 5:1) was stirred at 50 °C, for 5h. The resulting mixture was concentrated. Column chromatography (silica, hexanes/CH2Cl2 2:1) afforded a brown green solid; 2.2 mg, 40%; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −1.96 (s, 1H), −1.49 (s, 1H), 1.73 (s, 3H), 1.77 (s, 3H), 1.79 (s, 6H), 1.90 (s, 6H), 2.03 (s, 3H), 2.04 (s, 3H), 2.50 (s, 3H), 3.60 (d, J = 17.2 Hz, 1H), 3.70 (d, J = 17.3 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (d, J = 16.9 Hz, 1H), 3.86 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 4.50 (s, 2H), 4.55 (s, 3H), 7.15 (s, 2H), 7.61 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (dd, J = 1.7, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.43(d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.54 (dd, J = 1.8, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.71 (s, 1H), 8.75–8.78 (m, 4H), 8.86 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 9.02 (dd, J = 2.1, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 9.73 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 21.3, 21.5, 22.8, 29.5, 29.9, 30.5, 30.8, 31.3, 31.5, 32.1, 45.1, 45.5, 46.0, 47.8, 50.6, 52.3, 65.5, 95.9, 97.3, 97.3, 97.9, 100.1, 100.9, 111.7, 112.0, 118.0, 121.3, 122.9, 123.3, 123.7, 126.9, 127.0, 127.1, 127.8, 127.9, 130.8, 131.9, 132.1, 135.4, 136.1, 136.3, 137.3, 137.6, 137.8, 137.9, 138.7, 138.9, 139.0, 145.9, 147.1, 151.2, 153.9, 161.6, 161.7, 169.0, 169.3;MS ([M]+, M = C56H54N8OPd): Calcd: 960.3469, Obsd: (HRMS, ESI) 960.3456.

PdC

A solution of H2C (10.0 mg, 0.022 mmol) and Pd(OAc) 2 (14.7 mg, 0.065 mmol) in chloroform/MeOH mixture (10 mL, 5:1) was stirred at room temperature, for 7h. The resulting solution was concentrated. Column chromatography (silica, hexanes/CH2Cl2 2:1) afforded a red solid; 10.9 mg, 89% 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 1.84 (s, 6H), 2.02 (s, 6H), 2.60 (s, 3H), 4.58 (s, 2H), 7.23 (s, 2H), 8.40 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 8.45 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 8.54 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 8.68 (s, 1H), 8.71 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 8.74 (s, 1H), 8.81 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 8.96 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 9.67 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 21.2, 21.6, 31.0, 45.6, 50.2, 95.5, 97.7, 110.0, 122.5, 126.8, 126.9, 127.0, 127.8, 127.9, 131.1, 131.9, 137.1, 137.5, 137.6, 137.7, 138.5, 138.5, 139.0, 144.6, 145.6, 149.9, 161.6; MS ([M]+, M = C31H28N4Pd): Calcd: 562.1355, Obsd: (HRMS, ESI) 562.1354.

PdC-C

A mixture of 2C (21.9 mg,0.024 mmol) and Pd(OAc) 2 (5.4 mg, 0.024 mmol) in chloroform/MeOH (20 mL, 5:1) was stirred at 50 °C, for 5h. The resulting mixture was concentrated. Column chromatography (silica, hexanes/CH2Cl2 2:1) afforded a green solid; 7.8 mg, 32% 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −1.74 (s, 1H), −1.41 (s, 1H), 1.80 (s, 3H), 1.80 (s, 3H), 1.84 (s, 3H), 1.86 (s, 1H), 1.88 (s, 6H), 1.92 (s, 6H), 2.50 (s, 3H), 2.53 (s, 3H), 3.76–3.92 (m, 4H), 7.14 (s, 1H), 7.16 (s, 1H), 7.18 (s, 1H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 4.8Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.38 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.45 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.52 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 8.72 (s, 1H), 8.76 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.87 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.95 (s, 1H), 8.96 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 9.00 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 9.03 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 9.28 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 9.74 (s, 1H), 9.85 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 21.4, 21.5, 21.6, 29.9, 30.5, 31.0, 31.3, 31.7, 45.1, 46.2, 50.9, 52.8, 94.8, 96.0, 106.8 110.0, 110.9, 112.0, 121.5, 123.8, 123.9, 126.9, 127.1, 127.2, 127.8, 128.0, 128.3, 130.9, 131.7, 132.2, 132.8, 134.5, 135.2, 137.2, 137.6, 137.7, 138.0, 138.2, 138.7, 138.9, 139.0, 139.2, 139.2, 141.1, 141.9, 146.0, 147.2, 151.4, 152.1, 152.6, 161.8, 165.0, 175.3; MS ([M+H]+, M = C62H56N8Pd): Calcd: 1019.3756, Obsd: (HRMS, ESI) 1019.3762

2PdC

A mixture of 2C (12.9 mg, 0.014 mmol) and Pd(OAc) 2 (19.0 mg, 0.084 mmol) in chloroform/MeOH (10 mL, 5:1) was stirred at 50 °C for 5h. The resulting mixture was concentrated. Column chromatography (silica, hexanes/CH2Cl2, 2:1) afforded a green solid; 14.2 mg, 90%; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 1.81(s, 6H), 1.84 (s, 6H), 1.88 (s, 6H), 1.93 (s, 6H), 2.52 (s, 6H), 3.81 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 2H), 3.92 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (s, 2H), 7.18 (s, 2H), 7.66 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 8.19 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 8.44 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H), 8.72 (s, 2H), 8.76 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H), 8.86 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H), 9.01 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H), 9.72 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 21.3, 21.4, 21.5, 30.6, 31.2, 45.2, 50.9, 96.0, 109.9, 111.5, 124.0, 126.9, 127.1, 127.2, 127.8, 128.0, 130.8, 132.2, 137.2, 137.6, 137.7, 138.0, 138.7, 138.9, 139.0, 146.0, 147.0, 151.2, 161.8; MS ([M+H]+, M = C62H54N8Pd2): Calcd: 1125.2643, Obsd: (HRMS, ESI) 1125.2640.

ZnC-C

A mixture of 2C (30.0 mg, 0.033 mmol) and Zn(OAc) 2 (6.0 mg, 0.033 mmol) in chloroform/MeOH (30 mL, 5:1) was stirred at 50 °C, for 3h. The resulting solution was concentrated. Column chromatography (silica, hexanes/CH2Cl2 3:2) afforded a green solid; 13.6 mg, 42% 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ −1.72 (s, 1H), −1.41 (s, 1H), 1.79 (s, 3H), 1.81 (s, 3H), 1.84 (s, 3H), 1.88 (s, 3H), 1.89 (s, 3H), 1.91 (s, 3H), 1.93 (s, 1H), 1.94 (s, 1H), 2.51 (s, 3H), 2.54 (s, 3H), 3.66–3.75 (m, 2H), 3.82–3.94 (m, 2H), 7.15 (s, 1H), 7.16 (s, 1H), 7.18 (s, 1H), 7.20 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 4.6Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.25 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.38 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 8.53 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 8.64 (s, 1H), 8.82 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 8.89 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 8.96–8.97 (m, 2H), 9.00 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 9.16 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 9.28 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 9.67 (s, 1H), 9.85 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 21.4, 21.5, 21.6, 30.6, 31.0, 31.5, 31.8, 44.9, 46.2, 51.4, 53.2, 94.7, 94.8, 106.7, 109.4, 111.4, 112.0, 121.3, 123.6, 123.9, 127.0, 127.4, 127.5, 127.7, 127.8, 128.2, 128.3, 128.8, 131.6, 131.8, 132.8, 133.3, 134.5, 135.2, 137.3, 137.6, 138.3, 138.8, 138.9, 139.2, 139.3, 141.0, 142.2, 145.8, 146.5, 147.2, 147.3, 152.1, 152.6, 154.6, 156.0, 160.9, 165.3, 171.2, 175.1; MS ([M+H]+, M = C62H56N8Zn): Calcd: 977.3992, Obsd: (HRMS, ESI) 977.4012.

CuC-C

A mixture of 2C (15.0 mg, 0.016 mmol) and Cu(OAc) 2 (3.0 mg, 0.016 mmol) in chloroform/MeOH (15 mL, 5:1) was stirred at 50 °C, for 1h. The resulting solution was concentrated. Column chromatography (silica, hexanes/CH2Cl2 2:1) afforded the titled compounds as a green solid (8.9 mg, 57%) as well as 2CuC (green solid 4.0 mg, 24%). Data for CuC-C, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −1.89 (s, 1H), −1.66 (s, 1H), 1.85–1.88 (br, 12H) 2.31 (s, 3H), 2.58 (s, 3H), 6.91 (br, 2H), 7.21 (s, 2H), 8.48 (s, 2H), 8.88–8.95 (m, 3H), 9.25 (s, 1H), 9.82 (s, 1H); MS ([M]+, M = C62H56N8Cu): Calcd: 976.3997, Obsd: (HRMS, ESI) 976.4006. Data for 2CuC; MS ([M]+, M = C62H54N8Cu2): Calcd: 1036.3058, Obsd: (HRMS, ESI) 1036.3074.

5-Methoxy-8,8,18,18-tetramethyl-2,12-diphenylbacteriochlorin (BC1)

A solution of 1 (291 mg, 0.896 mmol) and 2,6-DTBP (4.0 mL, 17.92 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (180 mL) was for stirred for 0.5 h and then treated with TMSOTf (0.81 mL, 4.48 mmol) at room temperature. The reaction mixture was stirred for 16 h at room temperature. The reaction mixture concentrated and column chromatography was performed [silica, CH2Cl2/hexanes (1:1)] afforded a green solid (116 mg, 47%): 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ −1.77 (s, 1H), −1.66 (s, 1H), 1.95 (s, 6H), 1.99 (s, 6H), 4.40 (s, 2H), 4.47 (s, 2H), 4.56 (s, 3H), 7.64–7.68 (m, 2H), 7.80–7.85 (m, 4H), 8.26 (d, J = 7.0, 2H), 8.32 (d, J = 7.0, 2H), 8.69 (s, 1H), 8.74 (d, J = 2.0, 1H), 8.86 (s, 1H), 8.89 (s, 1H), 9.06 (d, J = 2.2, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 14.3, 22.8, 30.3, 31.1, 31.8, 45.8, 46.2, 47.6, 51.9, 65.2, 95.8, 97.9, 116.5, 121.4, 127.3, 127.7, 129.2, 129.9, 131.2, 131.4, 133.0, 134.1, 134.9, 135.4, 135.7, 136.6, 137.3, 137.4, 153.0, 159.9, 169.7, 170.2; MS ([M]+, M = C37H36N4O): Calcd: 552.2884, Obsd: (HRMS, ESI) 552.2888.

BC1-Br

A solution of BC1 (21.5 mg, 0.027 mmol) in THF (15 mL) was treated room temperature with NBS (4.8 mg, 0.027 mmol). The resulting mixture was stirred for 15 min. Saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution was added. The resulting mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic extract was washed with brine, dried (Na2SO4), and concentrated. Column chromatography [silica, hexanes/CH2Cl2 (1:1)] afforded a green solid; 16.0 mg, 94%; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −1.95 (s, 1H), −1.74 (s, 1H), 1.93 (s, 12H), 4.42 (s, 2H), 4.51(s, 3H), 4.52 (s, 2H), 7.61–7.67 (m, 2H), 7.76–7.82 (m, 4H), 8.21–8.25 (m, 4H), 8.79 (s, 1H), 8.84 (s, 1H), 9.03 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 9.09 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H); MS ([M+H]+, M = C37H35BrN4O): Calcd: 632.604, Obsd: (MALDI-MS) 632.443.

BC1-B

A mixture of BC1-Br (20.2 mg, 32 μmol), 4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolane (46 μL, 320 μmol), triethylamine (89 μL, 640 μmol), and (PPh3)2PdCl2 (2.2 mg 3.2 μmol) in 1,2-dichloroethane (8 mL) was reacted as described in General Procedure at 85 °C for 16 hours. The reaction mixture was concentrated, and the residue was purified by column chromatography [silica, hexane/CH2Cl2, (1:1)] to provide a green solid (19.1 mg, 88%); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ −1.37 (s, 1H), −1.04 (s, 1H), 1.72 (s, 12H), 1.91 (s, 6H), 1.92 (s, 6H), 4.36 (s, 2H), 4.51 (s, 3H), 4.60 (s, 2H), 7.60–7.67 (m, 2H), 7.78–7.81 (m, 4H), 8.21 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 8.27 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 8.74 (s, 1H), 8.81 (s, 1H), 8.92 (s, 1H), 9.30 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 25.4, 29.9, 30.8, 31.5, 45.3, 46.6, 46.9, 53.3, 65.0, 84.4, 95.9, 96.8, 115.6, 123.3, 127.1, 127.6, 129.0, 129.1, 129.5, 131.4, 132.3, 133.3, 134.8, 136.2, 136.9, 137.4, 138.6, 141.4, 151.9, 166.4, 169.1, 169.7; MS ([M]+, M = C43H47BN4O3): Calcd: 678.3743, Obsd: (HRMS, ESI) 678.3739.

BC1-Tol

Samples of BC1-Br (15.5 mg, 0.024 mmol), 4-tolylboronic acid pinacol ester (5.2 mg, 0.024 mmol), (Pd(PPh3)4 (2.8 mg, 0.0024 mmol), K2CO3 (33.2 mg, 0.240 mmol), in toluene/DMF (6 mL, 2:1), was reacted as described in General Procedure at 85 °C under N2 for 18 hours. Column chromatography (silica, hexanes/CH2Cl2, 2:1) afforded a reddish green solid: 14.3 mg, 91%; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −1.79 (s, 1H), −1.56 (s, 1H), 1.84 (s, 6H), 1.93 (s, 6H), 2.64 (s, 3H), 4.04 (s, 2H), 4.42 (s, 2H), 4.53 (s, 3H), 7.47–7.51 (m, 2H), 7.54- 7.64 (m, 2H), 7.69–7.72 (m, 2H), 7.75–7.81 (m, 4H), 8.10–8.12 (m, 2H), 8.22 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.26–8.28 (m, 2H), 8.82 (s, 1H), 8.85 (s, 1H), 8.99 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 21.7 31.0, 31.2, 47.5, 52.0, 65.3, 96.0, 96.2, 116.4, 121.7, 127.3, 127.5, 128.7, 129.0, 129.1, 130.3, 131.3, 131.4, 132.2, 133.0, 134.5, 134.6, 135.2, 136.2, 136.6, 136.8, 137.0, 140.0, 153.7, 159.6, 169.6; MS ([M]+, M = C44H42N4O): Calcd: 642.3353, Obsd: (HRMS, ESI) 642.3359.

2BC1

A solution of BC1-Br (10.0 mg, 16 μmol), BC1-B (11.0 mg, 16 μmol), Cs2CO3 (52.1 mg, 160 μmol), and Pd(PPh3)4 (5.5 mg, 4.8 μmol) in toluene/DMF (9 mL, 2:1) was reacted as described in General Procedure at 85 °C under for 18 hours. The mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate, washed (water and brine), dried (Na2SO4), and concentrated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (hexane/CH2Cl2, 1:1) to give a pink solid (7.2 mg, 41%); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ −1.52 (s, 2H), −1.09 (s, 2H), 1.70 (s, 6H), 1.73 (6H), 1.98 (s, 6H), 2.02 (s, 6H), 3.65 (d, J = 17.1 Hz, 2H), 3.76 (d, J = 17.1 Hz, 2H), 4.51 (s, 4H), 4.58 (s, 6H), 7.34 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 4H), 7.62 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.78–7.81 (m, 6H), 7.85 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 4H), 8.30 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 4H), 8.91 (s, 2H), 8.93 (s, 2H), 9.08 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 29.9, 30.5, 31.1, 31.2, 31.6, 45.6, 46.2, 47.7, 52.2, 65.4, 96.1, 96.7, 112.3, 116.8, 121.8, 127.3, 127.4, 128.8, 129.2 130.6, 131.1, 131.4, 133.5, 134.2, 134.8, 135.4, 136.4, 136.9, 137.1, 137.8, 154.0, 162.1, 169.8. HRMS ([M+H]+, M = C74H70N8O2): Calcd: 1103.5695, Obsd: (HRMS, ESI) 1103.5676.

BC-BC1

A solution of BC1-Br (7.6 mg, 12 μmol), BC-B (6.3 mg, 12 μmol), Cs2CO3 (39.1 mg, 120 μmol), and Pd(PPh3)4 (4.2 mg, 3.6 μmol) in toluene/DMF (6 mL, 2:1) was reacted as described in General Procedure at 85 °C under N2 for 18 hours. The mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate, washed (water and brine), dried (Na2SO4), and concentrated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (hexane/CH2Cl2, 1:1) to give a pink solid (5.5 mg, 48%); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −1.92 (s, 1H), −1.52 (s, 1H), −1.46 (s, 1H), −1.10 (s, 1H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.69 (s, 3H), 1.74 (s, 3H), 1.75 (s, 3H), 1.99 (s, 3H), 2.01 (s, 3H), 2.03 (s, 3H), 2.04 (s, 3H), 3.57–3.75 (m, 4H), 4.50 (s, 4H), 4.56 (s, 3H), 4.58 (s, 3H), 7.29–7.34 (m, 1H), 7.41–7.44 (m, 2H), 7.59–7.63 (m, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.83 (m, 5H), 8.29–8.31 (m, 2H), 8.53 (dd, J = 1.9, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.75–8.78 (m, 3H), 8.90 (s, 1H), 8.92 (s, 1H), 9.02 (dd, J = 1.9, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 9.07 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H). Due to the low solubility, no satisfactory 13C NMR spectra have been obtained. MS ([M]+, M = C62H62N8O2): Calcd: 950.4990, Obsd: (HRMS, ESI) 950.4992.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

Preparation of chlorin dyads relies on a PIFA-mediated dimerization of the ZnC monomer10,12 and subsequent demetalation of the resulting 2ZnC leading to the free-base 2C.12 Non-symmetrical metal complexes were prepared by a statistical metalation of 2C with corresponding metal acetates, in CHCl3/MeOH (Scheme 1) which affords mono-metalated ZnC-C, PdC-C, and CuC-C in moderate yield (42%, 32%, and 57% yield, respectively). Metalation, even when conducted with the 1 equiv of metal salt, leads to the formation of the mixture of mono- and di-metalated dyads, which can be separated by a column chromatography, however, formation of di-metalated product significantly diminished the yield of the target mono-metalated dyads. Synthesis of 2PdC was accomplished by refluxing of the 2C with an excess of Pd(OAc)2 in 90% yield, while 2CuC was isolated as a side product in synthesis of CuC-C in 24% yield.

Scheme 1.

Metallation of 2C.

For synthesis of chlorin-bacteriochlorin and bacteriochlorin-bacteriochlorin dyads we applied a strategy employed previously for synthesis of analogous bacteriochlorin dyads, which entails Suzuki reaction as a key step.4,11,12,51 The required chlorins and bacteriochlorin building blocks, were either known compounds (i.e. C-Br31 and BC-B12), or were prepared analogously to those reported previously (Schemes 2–4). Thus, BC1 was prepared through TMSOTf-mediated self-condensation52 of dihydrodipyrrin 1, (the latter was prepared following the route reported previously for analogous dihydrodipyrrins, see Scheme S1). Bromination of BC1 by NBS52 afforded BC1-Br in 94% yield (Scheme 2). Subsequent Suzuki reaction of BC1-Br with BC-B12 afforded dyad BC-BC1 in 48% yield. Similarly, Suzuki reaction of C-Br31 with BC-B afforded C-BC in 36% yield (Scheme 3). Metalation of the C-BC with Pd(OAc)2 provides selectively PdC-BC in 40% (Scheme 3). No bacteriochlorin metallation was observed under this condition, which is consistent with the previous report that metallation of synthetic bacteriochlorins required harsher condition (i.e. strong base) than metallation of chlorins.29

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of BC-BC1.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of symmetrical 2BC1 dyad.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of chlorin-bacteriochlorin dyads C-BC and PdC-BC.

Symmetrical 2BC1 dyad was prepared in Suzuki reaction of BC1-B (prepared in Miyaura reaction of BC1-Br with 2, in 88% yield) with BC1-Br in 41% yield (Scheme 4). Note, that attempted synthesis of symmetrical bacteriochlorin dyads by PIFA-mediated dimerization of corresponding monomers (either free base or Zn(II) complex) were unsuccessful. Benchmark monomer BC1-Tol was prepared in Suzuki reaction of BC1-Br with corresponding boronic ester in 91% yield (Scheme 5), while PdC were prepared by the metallation of H2C30 with Pd(OAc)2 in 89% yield (Scheme 6).

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of benchmark monomer BC1-Tol.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of PdC

Characterization

Resulting dyads were characterized by 1H, 13C NMR and HRMS. The data are consistent with the proposed structures. In particular, each 1H NMR spectra of non-symmetrical dyads consist of resonances of protons from two different hydroporphyrins. Resonances of protons at the 17-postions of each hydroporphyrin in each dyad are significantly shifted upfield (~1 ppm) compared to monomers (Figure S1). This effect is consistent with the orthogonal mutual arrangement of the macrocycles, which places the protons at 17 position within a shielding cone of neighboring macrocycle. Moreover, each dyad (symmetrical and non-symmetrical) is axially chiral, which is manifested by a differentiation of proton shifts of the respective diastereotopic protons, observed in 1H NMR (specifically H17 and these of geminal CH3 groups, see Figure S1). The DFT calculations confirm a nearly perpendicular arrangement of macrocycles in dyads (Figure S2), with the dihedral angles between macrocycles 180° ± 2°. The orthogonal geometry of these dyads is relatively stable, as the temperature-dependent 1H NMR spectra for 2C and 2BC in CDCl3 do not show noticeable changes in the chemical shift of protons up to 50 °C. Moreover, DFT calculations suggest that the energy barrier for rotation around C15-C15 single bond is at least 150 kJ/mol (Table S1).

Absorption and emission properties

Absorption spectra of dyads are presented in Figures 1–2, and summarized in Table 1 (spectra of corresponding monomers are presented in Figures S3–S4, SI). The spectrum of each symmetrical dyad shows features characteristic of given hydropoprhyrins,18,28 with the maximum of long-wavelength Qy band shifted bathochromically, compared to both corresponding monomers and 15-aryl-substituted monomers (Table 1. Note, that formally, use of Qy, B, etc. descriptions for absorption bands in dyads is incorrect, however, for simplicity, we use this notation to describe absorption spectra of both monomers and dyads). Metal complexation of the dyads causes a significant hypsochromic shift of the Qy band [by 27 nm, 46 nm, and 30 nm, for Zn(II), Pd(II), and Cu(II), respectively], which is similar to those observed for monomers.28,33 Note that for 2PdC, 2CuC, 2ZnC, and 2C, the Qy band shows a slight shoulder on the short wavelength side, whereas for 2BC and 2BC1, a new distinctive band appears at the shorter wavelength to the Qy band. This splitting is probably due to the exciton coupling between macrocycles.56 For non-symmetrical chlorin-chlorin and chlorin-bacteriochlorin dyads, absorption spectra show two distinctive Qy bands, for which the maxima are slightly shifted hypsochromically, compared to that of symmetrical dyads (e.g. compare 2ZnC with ZnC-C, 2BC with C-BC, and 2BC1 with BC-BC1). The metal complexation has a negligible effect on the absorption wavelength of the neighboring free-base hydroporphyrin component (e.g. compare absorption of the free base chlorin in ZnC-C with that of PdC-C and C-BC with that in ZnC-BC). Chlorin-bacteriochlorin dyads also exhibit distinctive, clearly resolved the B bands (i.e. shortest wavelength bands), whereas for chlorin-chlorin dyads B band of individual dyads components overlap.

Figure 1.

Absorption spectra of symmetrical dyads in toluene: 2PdC (black), 2ZnC (blue), 2CuC (orange), 2C (red), 2BC (green), and 2BC1 (purple). All spectra were taken at the room temperature and normalized at the maximum of their B bands.

Figure 2.

Absorption spectra of non-symmetrical dyads in toluene: PdC-C (black), ZnC-C (blue), CuC-C (orange), C-BC (red), PdC-BC (green), and BC-BC1 (purple). All spectra were taken at the room temperature and normalized at the maxima of their B bands.

Table 1.

Absorption and photochemical properties of hydroporphyrin dyads and benchmark monomers.

| Compound | λabsa | λema | Φf (toluene)b | Φf (DMF) | ETEc | ΦΔd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Ce | 421, 508, 650 | 654 | 0.31 | 0.29 | - | 0.53 |

| 2ZnC | 408, 419, 623 | 628 | 0.15 | 0.032 | - | 0.48 |

| 2PdC | 408, 604 | - | < 0.005 | < 0.005 | - | 1.00 |

| 2CuC | 415, 620 | - | < 0.005 | < 0.005 | - | < 0.03 |

| 2BCe | 372, 510, 706, 731 | 738 | 0.28 | 0.003 | - | 0.65 |

| 2BC1 | 386, 524, 729, 754 | 760 | 0.27 | 0.013 | - | |

| ZnC-C | 408, 419, 506, 613, 646 | 646 | 0.31 | <0.005f | > 0.95g | 0.54 |

| PdC-C | 417, 596, 646 | 645 | 0.05 | 0.04 | > 0.95g | 0.90 |

| CuC-C | 419, 506, 610, 646 | - | < 0.005 | < 0.005 | - | 0.86 |

| C-BC | 366, 399, 512, 642, 719 | 719 | 0.24 | <0.005 | 0.99 | 0.65 |

| PdC-BC | 366, 398, 510, 595, 718 | 718 | 0.11 | <0.005 | 0.86 | 0.74 |

| BC-BC1 | 381, 520, 713, 746 | 754 | 0.29 | 0.007 | - | 0.62 |

| H2Ch | 393,399, 498, 636 | 636 | 0.22 | 0.22 | - | 0.44 |

| ZnCh | 403, 604 | 605 | 0.08 | 0.08 | - | - |

| PdC | 396,588 | 589 | < 0.005 | < 0.005 | - | - |

| BC1 | 372, 510, 731 | 737 | 0.21 | 0.20 | - | - |

| BC-Tol | 369, 508, 712 | 715 | 0.22 | 0.20 | - | - |

| BC1-Tol | 375, 518, 734 | 736 | 0.24 | 0.21 | - | - |

| H2C-Phi | 411, 640 | - | - | - | - | - |

All data taken in toluene at the room temperature.

Fluorescence quantum yield Φf was determined in air-equilibrated solvents upon excitation at the maximum of the B band of corresponding chlorin. Φf was determined using tetraphenylporphyrin in air-equilibrated toluene (Φf = 0.07053) as a reference. Estimated error ± 5%. A long bandpass filter (with cut off 600 nm) was used for each Φf determination to eliminate subharmonic band from excitation.

Energy transfer efficiency ETE (all data in toluene) was determined as a ratio of Φf of the component with longer emission wavelength (energy acceptor) upon excitation at the chlorin B band to the same Φf obtained upon excitation at the maximum of the bacteriochlorin B band (unless noted otherwise).

Quantum yield of 1O2 photosensitization ΦΔ was determined by comparing the 1O2 luminescence intensity (λem = 1270 nm) to that generated by tetraphenylporphyrin in air-equilibrated toluene (ΦΔ = 0.6754). Samples were excited at the maximum of the B band. Estimated error ± 10%.

Data taken from ref. 12).

Φf is approximate, due to the very weak emission and presence of an additional weak peak at 660 nm of unknown origin (most likely a trace amount of 2C impurity).

ETE was determined by comparing absorption and fluorescence excitation spectra, monitored at the wavelength where energy acceptor emits exclusively.

All data (except ΦΔ) for H2C,28,55 and ZnC,28,55 were reported previously. For consistency, all data for these compounds reported here were re-determined in our laboratory, and are consistent with those reported previously.

Data taken from ref. 31.

The absorption spectrum of BC-BC1 is different from those of other non-symmetrical hydroporphyin dyads reported here, since it consists of a strong band at 746 nm, and a much weaker shoulder at 713 nm, and no distinguishable Qy bands from individual bacteriochlorins. This pattern resembles those observed for symmetrical 2BC1 and 2BC.

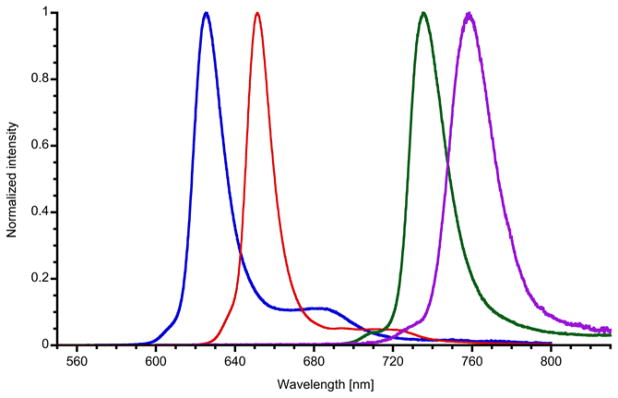

Emission spectra of symmetrical dyads 2C, 2ZnC, 2BC and 2BC1, as well as BC-BC1 in toluene (Figure 3, Table 1; for spectra of corresponding monomers see Figures S5 and S6) show a strong 0–0 band with a small Stokes shift (0 – 5 nm), similar to the analogous monomers.57 Emission spectra of non-symmetrical dyads ZnC-C, PdC-C, C-BC, and PdC-BC predominantly show one strong band, with the wavelength corresponding to emission of the longer-wavelength absorbing component, regardless of the excitation wavelength. There is a second, very weak emission band at the shorter wavelength, corresponding to the short-wavelength absorbing component. Excitation spectra of each dyad, monitored at the main emission peak, closely resemble the absorption spectra. These results indicate a very efficient energy transfer from the shorter to the longer-wavelength absorbing hydroporphyrin components. Comparison of excitation and absorption spectra allowed estimation of the energy transfer efficiency (ETE) as > 0.95 for most of the dyads, except for PdC-BC, for which ETE of 0.86 was determined. It is interesting to note, that high ETE is observed even from the Pd(II)-coordinated chlorin, despite very fast intersystem crossing (ISC) in the monomer PdC, as well as 2PdC (which is manifested by a significant reduction of the fluorescence quantum yield Φf, see below). Apparently, S1-S1 energy transfer from the Pd(II) chlorin to the directly linked hydroporphyrin is faster than ISC (S1-S1, rather than T1-T1 as a dominant ET mechanism, is indicated by the similarity of Φf of the free base component regardless of the excitation wavelength). 2PdC shows a very weak fluorescence, while both 2CuC and CuC-C are essentially non-fluorescent, regardless of excitation wavelength.

Figure 3.

Emission spectra of symmetrical dyads in toluene: 2ZnC (blue), 2C (red), BC (purple), 2BC (green), and 2BC1 (purple). All spectra were taken at room temperature and normalized at the maxima of their emission bands.

Φf for symmetrical chlorin and bacteriochlorin dyads in toluene are markedly higher (1.2–1.9-fold) than for the corresponding monomers (Table 1). For non-symmetrical dyads ZnC-C, and BC-BC1, Φf in toluene is similar to that determined for the respective symmetrical dyads (2C, and 2BC1), while Φf for C-BC is more similar to monomer BC. Note, that insertion of Zn(II) in chlorin does not affect Φf of non-symmetrical dyads. In contrast, Φf for PdC-C and PdC-BC is significantly reduced compared to the corresponding free base analogs (6.2-fold and 2.5-fold, respectively). This Φf reduction is most likely due to the “remote” heavy atom effect, i.e. enhancement of ISC of the free base hydroporphyrin component by Pd(II) complexation of the neighboring macrocycle. Similar reduction of Φf, attributed to enhanced ISC, has been reported previously for the chlorin-bispyridine-Ru(II) dyad.48 We cannot however rule out other processes, such as photoinduced electron transfer, being responsible for reduction of Φf in PdC-C and PdC-BC. More detailed spectroscopic studies are required to clarify this issue.

Effect of solvent dielectric constant on dyads fluorescence

Φf for non-symmetrical dyads ZnC-C, C-BC, PdC-C, and BC-BC1 as well as for symmetrical bacteriochlorin dyads 2BC and 2BC1, exhibit a dramatic reduction (more than 40 times) in DMF compared to that observed in toluene (Table 1; for Φf of ZnC-C and BC-BC1 in range of solvents of different ε, see Table 2). Reduction of Φf in DMF is also observed, albeit to a lesser degree for 2ZnC (4.7 fold) and PdC-C (1.25 fold). Φf for 2C and all examined monomers (chlorins and bacteriochlorins) are nearly the same in DMF and toluene. Observed reduction of Φf in polar solvents is consistent with the PET, which may occur in polar solvents (such as DMF). Solvents of high ε stabilizes charge-separated state, formed upon electron transfer and thus make PET energetically possible (in solvents of low ε energy of charge-separated state is higher than energy of S1).27 It is know that bacteriochlorins are easier to oxidize and harder to reduce than analogous chlorins,23 and similarly Zn(II) chlorins are significantly easier to oxidize and slightly harder to reduce than chlorin free bases.28 Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that in ZnC-C, the metalated chlorin is an electron donor, while the free base chlorin is an electron acceptor. Similarly, in C-BC the bacteriochlorin component is an electron donor. On the other hand, Pd(II) chelates of chlorins are only slightly easier to oxidize and slightly harder to reduce than corresponding free bases.10,58 Thus, the observed reduction of Φf in DMF for PdC-C is much less pronounced (1.25 fold, compared to toluene) than that for ZnC-C. For BC1-BC the direction of electron transfer is less obvious, however a inspection of available redox data for monomers, analogous to that composing BC-BC1, lead to conclusion that photoexcited 2,12-diphenylbacteriochlorin component is an electron donor.29,59 Further detailed studies are required to fully understand PET processes occurring in all dyads reported here.

Table 2.

Φf for ZnC-C and BC-BC1 in solvents of different dielectric constants.

| Dyad | Solvent | Φf |

|---|---|---|

| ZnC-C | Toluene | 0.31 |

| THF | 0.061 | |

| CH2Cl2 | 0.17 | |

| PhCN | ~ 0.006 | |

| DMF | < 0.005 | |

| BC-BC1 | Toluene | 0.29 |

| THF | 0.14 | |

| CH2Cl2 | 0.028 | |

| DMF | ~ 0.007 |

Note, that for ZnC-C Φf in THF (ε = 7.58) is much lower than in CH2Cl2 (ε = 8.93). We speculate, that coordination of THF to Zn(II) alters significantly redox properties of ZnC component of dyad and facilitates PET.

Effect of metalation on the singlet oxygen (1O2) photosensitization

The relative quantum yield of 1O2 photosensitization was determined by comparing 1O2 luminescence intensity at 1270 nm generated by dyads, to that observed for tetraphenylporphyrin (ΦΔ = 0.6754). ΦΔ determined for ZnC-C and C-BC (0.56 and 0.65, respectively) correspond well with those reported previously for analogous chlorins60 and bacteriochlorins.12 Insertion of Pd(II) into the macrocycle enhances ΦΔ significantly for 2PdC (up to 1.00), and PdC-C (1.7-fold compared to 2C), but only slightly for PdC-BC (1.1-fold compared to C-BC). Direct excitation at the longest absorption band indicates that 1O2 photosensitization efficiency of the free base component in PdC-C increases 1.5-fold (compared to 2C), and 1.2-fold for the BC component in PdC-BC (compared to C-BC). Combining both fluorescence data and 1O2 photosensitization experiments together, it is reasonable to assume, that excitation of the PdC component in PdC-C and PdC-BC leads to the (predominantly) S1-S1 energy transfer to the free base chlorin or bacteriochlorin 1O2 photosensitization mainly occurs through ISC in the dyads free base component, where ISC is enhanced due to the “remote” heavy atom effect of Pd in the neighboring macrocycle (enhanced ISC in dyad free base hydroporphyrin components is inferred by both substantial reduction of Φf and enhanced ΦΔ). Note that the extent of Φf reduction (5-fold for PdC-C vs. ZnC-C and 2.2-fold for PdC-BC vs. C-BC) is much larger than the respective increase in ΦΔ (1.7-fold for PdC-C and 1.1 for PdC-BC). However, increase in ISC quantum yield does not always result in the same increase in ΦΔ, as the latter depends on both yield and lifetime of T1,61 and enhanced ISC is usually accompanied by a decrease in T1 lifetime.29,36 In polar solvent (DMF) ΦΔ is reduced to ~0 for ZnC-C and C-BC, while for PdC-C and PdC-BC 1O2 emission could still be seen in DMF, though we did not attempt to quantify ΦΔ in DMF.

For 2CuC excitation in toluene leads to a negligible 1O2 production, while for CuC-C, efficient 1O2 photosensitization is observed (ΦΔ = 0.86; direct excitation of free base component shows 1.4-fold increase in 1O2 photosensitization, compared to 2C). It has been previously reported that excitation of the Cu(II) complexes of porphyrins and bacteriochlorins leads to the ultrafast formation of tripdoublet 2T or tripquartet 4T states, which decay to the ground state within nanosecond time range.29,62 Due to this short-lived triplet state, Cu(II) complexes of tetrapyrrolic macrocycles usually show very low ΦΔ.54 On the other hand, in non-symmetrical porphyrin dyads containing Cu(II) and free-base porphyrins, enhanced ISC in the free base component has been observed due to the through-bond exchange electron interaction.42,43 This latter mechanism most likely operates for CuC-C.

Electronic properties

The absorption and emission properties indicate substantial electronic interactions between macrocycles in both symmetrical and non-symmetrical directly-linked dyads. This interaction is manifested by the bathochromic shift of the absorption Qy and emission bands of dyad components, and increase in dyad Φf, compared to monomers (both unsubstituted and 15-arylsubstituted). In the non-symmetrical chlorin-chlorin and chlorin-bacteriochlorin, each dyad component maintains its individual identity, as indicated by the presence of clearly distinctive Qy bands for each hydroporphyrin. In case of BC-BC1, interactions between macrocycles leads to significant alteration of the absorption spectrum, which no longer preserves the features of individual chromophores. Based on the above consideration we concluded, that the strength of interchromophoric interactions decreases in the following order: symmetrical bacteriochlorin-bacteriochlorin ~ symmetrical chlorin-chlorin > non-symmetrical bacteriochlorin-bacteriochlorin > non-symmetrical chlorin-chlorin > chlorin-bacteriochlorin. This trend is additionally supported by the degree to which Pd(II) coordination reduces Φf and increases ΦΔ in the adjacent macrocycle (i.e. PdC-C > PdC-BC).

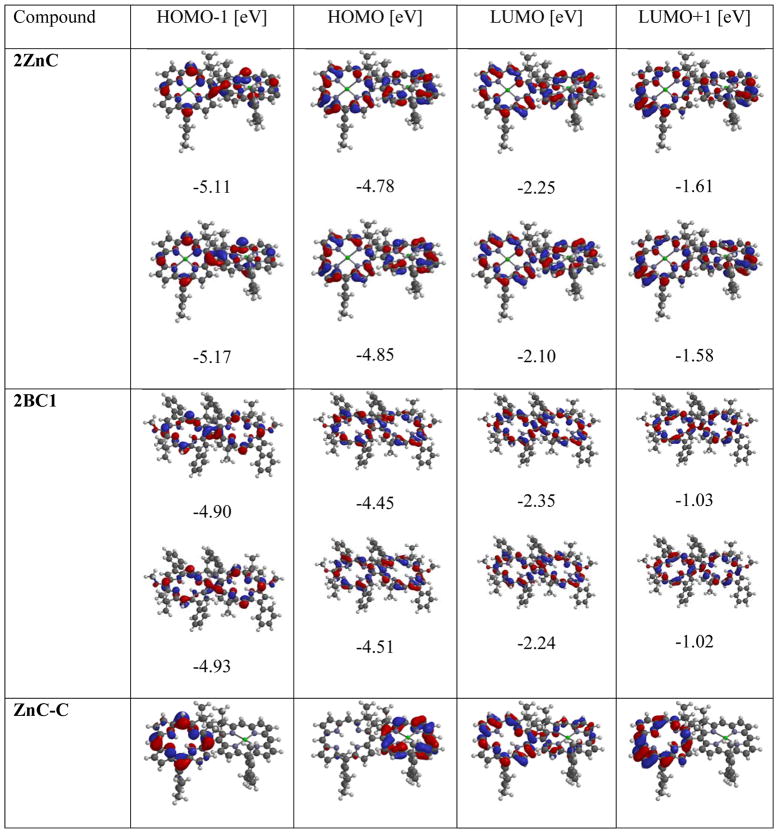

Further insight into electronic structure and the interchromophoric interaction in dyads has been obtained from DFT calculations. Here, only a basic discussion is presented; detailed computational characterization and comprehensive discussion of results will be presented in due publication. Four MOs are considered (HOMO-1, HOMO, LUMO, and LUMO+1), since according to the Gouterman theory the configuration interactions of electronic transitions between these MOs (i.e. HOMO → LUMO, HOMO → LUMO+1, etc.), give rise to the absorption features of tetrapyrrolic macrocycles.63 The energies and shapes of the relevant MOs (HOMO-1, HOMO, LUMO, and LUMO+1) for representative symmetrical and non-symmetrical dyads and monomers are given in Table 3. For symmetrical 2ZnC and 2BC1, linear combination of MOs of monomers results in a new set of MO, fully delocalized on the entire dyad. Thus, for 2ZnC combination of HOMO of both monomers results in new MOs (now formally HOMO and HOMO-1 of dyad) with an energy difference ΔE = 0.07 eV. Similarly, combinations of LUMO of both ZnC components leads to LUMO and LUMO+1 of 2ZnC (ΔE = 0.15 eV), combination of HOMO-1 of ZnC gives HOMO-2 and HOMO-3 of 2ZnC (ΔE = 0.06 eV), and combination of LUMO+1 of both monomers gives LUMO+2 and LUMO+3 of dyad (ΔE = 0.04 eV). The identical pattern of splitting is observed for 2BC1, where ΔE(HOMO) = 0.06 eV, ΔE(LUMO) = 0.11 eV, ΔE(HOMO-1) = 0.03, and ΔE(LUMO+1) = 0.01 eV. Similar combination of MOs of monomer has been observed in strongly conjugated hydropoprhyrin dyads.22

Table 3.

DFT calculated FMOs for representative dyads and benchmark monomers.a

All calculations was conducted employing the DFT B3LYP 6–31G* method. For symmetrical dyads as “HOMO”, “HOMO-1”, etc., two orbitals, formed from linear combination of respective MOs of corresponding monomers are listed. For non-symmetrical dyads, pairs of MOs, corresponding to respective MOs localized on each individual macrocycle, are listed (e.g. as a “HOMO” for ZnC-C, a MOs with the highest energy localized on free base and Zn complex, are listed, etc.).

For ZnC-C and C-BC, MOs are localized nearly entirely on the single macrocycle; thus HOMO is localized on Zn chelate and bacteriochlorin components of the ZnC-C and C-BC, respectively. Shapes and energies of these MOs resemble that of corresponding HOMO of ZnC and BC benchmarks, respectively (both MOs are stabilized by 0.04 eV for C-BC and 0.06 eV for ZnC-BC, compared to the benchmark monomers). Similarly, formal HOMO-1 for ZnC-C and C-BC are localized at the chlorin moiety, and their distribution and energies are similar to HOMO in H2C. Conversely, LUMOs for ZnC-C and C-BC maintain LUMO character of H2C and BC, respectively (energies of LUMO in dyads are lower by 0.09 eV for C-BC and 0.11 eV for C-BC, compared to their counterparts in monomers). Similarly, HOMO-1 and HOMO-2 as well as LUMO+1 and LUMO+2 in ZnC-C and C-BC essentially possess a characteristic of the relevant orbitals in monomers. This situation is different in BC-BC1, where both HOMO and HOMO-1 resulted from the linear combination of HOMOs of the monomers. Both MOs are delocalized over the entire molecule, and the difference of energy difference between them ΔE = 0.07 eV. The same is true for HOMO-2 and HOMO-3 of BC-BC1, which resulted from a linear combination of HOMO-1 of monomers (ΔE = 0.04 eV). In this regard, BC-BC1 resemble more symmetrical dyads. However, LUMO and LUMO+1 (as well LUMO+2 and LUMO+3) are mostly localized on the one macrocyle, and maintain characteristics of relevant MOs in monomers (i.e. LUMO of BC-BC1 resembles LOMO of BC1, LUMO+1 resembles LUMO of BC, etc.).

The DFT calculations thus support our conclusion regarding the strength of the electronic interactions between hydroporphyrins, drawn from the spectroscopic data. For C-BC and ZnC-C individual macrocycles preserve to a large extent, their electronic structures characteristic for monomers, while for BC-BC1, new delocalized MOs resulted from a linear combination of HOMOs (as well as HOMO-1) are present. This difference in electronic structure (as well as optical properties) of BC-BC1, compared to other non-symmetrical dyads, is most likely a result of (coincidentally) the same energies of HOMOs (and nearly the same of HOMO-1) of the macrocycles constituting BC-BC1, whereas there is substantial difference in MOs energies in hydroporphyrins of which other dyads are composed (as well as between LUMO and LUMO+1 of BC and BC1). Therefore, BC-BC1 behaves more closely to analogous symmetrical dyads, despite the distinctive optical properties of its constituents. This conclusion emphasizes the importance of the monomers electronic structure to the properties of the resulting dyads. MOs energies in bacteriochlorins (as well as chlorins) can be broadly tuned by the peripheral substituents, and as such, the proper choice of monomers should allow for construction of directly-linked bacteriochlorin-bacteriochlorin dyads, where each macrocycle retain its individual characteristics, as in case of ZnC-C and (Pd)C-BC.

Conclusion

A range of directly-linked hydroporphyrin-hydroporphyrin dyads can be synthesized using either PIFA-mediated oxidative coupling (for chlorin-chlorin) or the Suzuki reaction (for chlorin-bacteriochlorin and bacteriochlorin-bacteriochlorin dyads), and subsequent symmetrical or non-symmetrical metalation of the resulting dyads. Hydroporphyrin dyads feature a range of interesting properties, depending on the electronic structure of constituent monomers. Symmetrical (or nearly symmetrical) arrays exhibit a marked bathochromic shift of the long-wavelength absorption bands, and enhanced Φf. In non-symmetrical dyads, each macrocycle maintains its individual properties, and a very efficient S1-S1 energy transfer is observed, even for dyads in which energy donor contains a heavy element (Pd). The influence of heavy elements (Pd(II) or Cu(II) on the properties of the adjacent macrocycle, manifested by reduction of Φf and increase in ΦΔ, has been clearly observed. Moreover, the photochemical properties of most of the dyads exhibit a strong dependence of their photochemical properties on the solvent dielectric constant, which is attributed to the PET. Overall, directly linked hydroporphyrin arrays constitute a useful platform for development of photonic agents for a variety of biomedical and energy-related applications. The dyads reported here are also useful tools for fundamental studies on energy and electron transfers in electronically coupled systems, the “remote” heavy atom effect, metal-metal interactions, etc.

Supplementary Material

Figure 4.

Emission spectra of non-symmetrical dyads in toluene: PdC-C (black), ZnC-C (blue), C-BC (red), PdC-BC (green), and BC-BC1 (purple). All spectra were taken at room temperature and normalized at the maxima of their emission bands.

Synopsis.

Symmetrical and non-symmetrical meso-meso linked chlorin-chlorin, chlorin bacteriochlorin and bacteriochlorin-bacteriochlorin dyads, (free base and Zn(II), Pd(II) or Cu(II) complexes) are reported. For non-symmetrical dyads an efficient singlet-singlet energy transfer is observed. Insertion of heavy element [Pd(II) or Cu(II)] significantly enhances 1O2 photosensitization. Most of the dyads exhibit a significant reduction of the fluorescence in highly polar solvents, suggesting a charge transfer character of the excited state.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NSF CHE-1301109. N.N.E. was partially supported by the Meyerhoff Scholars Program at UMBC, supported by the NIGMS Initiative for Maximizing Students Development Grant (Grant 2 R25-GM55036), and CBI Program at UMBC, supported by the NIH (Grant No. 5T32GM066706).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Synthesis of compound 1, additional discussion of the structure of dyads, additional absorption and emission spectra, computational data and copies of 1H and 13C spectra for new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Kim D, Osuka A. Directly linked porphyrin arrays with tunable excitonic interactions. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:735–745. doi: 10.1021/ar030242e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aratani N, Kim D, Osuka A. Discrete cyclic porphyrin arrays as artificial light-harvesting antenna. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:1922–1934. doi: 10.1021/ar9001697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camus JM, Aly SM, Fortin D, Guilard R, Harvey PD. Design of triads for probing the direct through space energy transfer in closely spaced assemblies. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:8360–8368. doi: 10.1021/ic3026655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filatov MA, Guilard R, Harvey PD. Selective stepwise Suzuki Cross-coupling reaction for the modeling of photosynthetic Donor-Acceptor Systems. Org Lett. 2010;12:196–199. doi: 10.1021/ol902614k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imahori H, Sekiguchi Y, Kashiwagi Y, Sato T, Araki Y, Ito O, Yamada H, Fukuzumi S. Long-lived charge-separated state generated in ferrocene-meso,meso-linked porphyrin trimer-fullerene pentad with a high quantum yield. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:3184–3196. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu M, Yu ZW, Liu Y, Feng DF, Yang JJ, Yin XB, Zhang T, Chen DY, Liu TJ, Feng XZ. Glycosyl-modified diporphyrins for in vitro and in vivo Fluorescence imaging. ChemBioChem. 2013;14:979–986. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sedghi G, Esdaile LJ, Anderson HL, Martin S, Bethell D, Higgins SJ, Nichols RJ. Comparison of the conductance of three types of porphyrin-based molecular wires: β,meso,β-fused tapes, meso-butadiyne-linked and twisted meso-meso linked oligomers. Adv Mater. 2012;24:653–657. doi: 10.1002/adma.201103109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clausen C, Gryko DT, Yasseri AA, Diers JR, Bocian DF, Kuhr WG, Lindsey JL. Investigation of tightly coupled porphyrin arrays comprised of identical monomers for multibit information storage. J Org Chem. 2000;65:7371–7378. doi: 10.1021/jo000489e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xun Z, Zeng Y, Chen J, Yu T, Zhang X, Yang G, Li Y. Pd-Porphyrin Oligomers Sensitized for Green-to-Blue Photon Upconversion: The More the Better? Chem Eur J. 2016;22:8654–8662. doi: 10.1002/chem.201504498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ouyang Q, Yan KQ, Zhu YZ, Zhang CH, Liu JZ, Chen C, Zheng JY. An efficient PIFA-mediated synthesis of a directly linked zinc chlorin dimer via regioselective oxidative coupling. Org Lett. 2012;14:2746–2749. doi: 10.1021/ol300969g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiong R, Arkhypchuk AI, Kovacs D, Orthaber A, Borbas KE. Directly linked hydroporphyrin dimers. Chem Comm. 2016;52:9056–9058. doi: 10.1039/c6cc00516k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nopondo EN, Yu Z, Wiratan L, Satraitis A, Ptaszek M. Bacteriochlorin dyads as solvent polarity dependent near-Infrared fluorophores and reactive oxygen species photosensitizers. Org Lett. 2016;18:4590–4593. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koszarna B, Gryko DT. Meso-meso linked corroles. ChemComm. 2007:2994–2996. doi: 10.1039/b703279j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ooi S, Tanaka T, Osuka A. Metal complexes of meso-meso linked corrole dimers. Inorg Chem. 2016;55:8920–8927. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b01422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Kobayashi M, Akiyama M, Kano H, Kise H. In: Chlorophylls and Bacteriochlorophylls Biochemistry, Biophysics, Function and Applications. Grimm B, Porra RR, Rüdiger W, Scheer H, editors. Springer; 2006. pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]; (b) Blankenship RE. Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis. 2 Blackwell Sci; Malden, MA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindsey JS. De Novo Synthesis of Gem-Dialkyl Chlorophyll Analogues for Probing and Emulating Our Green World. Chem. Rev. 2015; 115: 6534–6620. (b) Taniguchi, M. Lindsey, J. S. Synthetic Chlorins, Possible Surrogates for Chlorophylls, Prepared by Derivatization of Porphyrins. Chem Rev. 2017;117:344–535. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brückner C, Samankumara L, Ogikubo J. In: Handbook of Porphyrin Sciences. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 17. World Scientific; River Edge, NY: 2012. pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang E, Kirmaier C, Krayer M, Taniguchi M, Kim HJ, Diers JR, Bocian DF, Lindsey JS, Holten D. Photophysical Properties and Electronic Structure of Stable, Tunable Synthetic Bacteriochlorins: Extending the Feature of Native Photosynthetic Pigments. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:10801–10816. doi: 10.1021/jp205258s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ethirajan M, Chen Y, Joshi P, Pandey RK. The Role of Porphyrin Chemistry in Tumor Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2011:340–362. doi: 10.1039/b915149b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grin MA, Mironov AF, Shtil AA. Bacteriochlorophyll a and its derivatives: chemistry and perspectives for cancer therapy. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2008;8:683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harada T, Sano K, Sato K, Watanabe R, Yu Z, Hanaoka H, Nakajima T, Choyke PL, Ptaszek M, Kabayashi H. Activatable Organic near-Infrared Fluorescent Probes Based on a Bacteriochlorin Platform: Synthesis and Multicolor in Vivo Imaging with a Single Excitation. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014;25:362–369. doi: 10.1021/bc4005238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng, Kenneth K, Zheng G. Molecular interactions in organic nanoparticles for phototheranostic applications. Chem Rev. 2015;115:11012–11042. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang CK, Hanson LK, Richardson PF, Young R, Fajer J. π Cation radicals of ferrous and free base isobacteriochlorins: model for siroheme and sirohydrochlorin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:2652–2656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho S, Yoon MC, Lim JM, Kim P, Aratani N, Nakamura Y, Ikeda T, Osuka A, Kim D. Structural factors determining photophysical properties of directly linked zinc(II) porphyrin dimers: linking position, dihedral angle, and linkage length. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:10619–10627. doi: 10.1021/jp904666s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang HS, Esemoto NN, Diers J, Niedzwiedzki D, Greco J, Akhigbe J, Yu Z, Pancholi C, Viswanathan BG, Nguyen JK, Kirmaier C, Birge R, Ptaszek M, Holten D, Bocian DF. Effects of strong electronic coupling in chlorin and bacteriochlorin dyads. J Phys Chem A. 2016;120:379–385. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.5b10686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu Z, Pancholi C, Bhagavathy GV, Kang HS, Nguyen JK, Ptaszek M. Strongly conjugated hydroporphyrin dyads: extensive modification of hydroporphyrins’ properties by expanding the conjugated system. J Org Chem. 2014;79:7910–7925. doi: 10.1021/jo501041b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wasielewski MR, Johnson DG, Niemczyk MP, Gaines GL, III, O’Neil MP, Svec WA. Chlorophyll-porphyrin heterodimers with orthogonal π system: solvent polarity dependent photophysics. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:6482–6488. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kee HL, Kirmaier C, Tang Q, Diers JR, Muthiah C, Taniguchi M, Laha JK, Ptaszek M, Lindsey JS, Bocian DF, Holten D. Effects of substituents on synthetic analogs of chlorophylls. Part 2: Redox properties optical spectra and electronic structure. Photochem Photobiol. 2007;83:1125–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen CY, Sun E, Fan M, Taniguchi M, McDowell BE, Yang E, Diers JR, Bocian DF, Holten D, Lindsey JS. Synthesis and photochemical properties of metallobacteriochlorin. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:9443–9464. doi: 10.1021/ic301262k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ptaszek M, McDowell BE, Taniguchi M, Kim HJ, Lindsey JS. Sparsely substituted chlorins as core constructs in chlorophyll analogue chemistry. Part 1: Synthesis. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:3826–3839. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muthiah C, Ptaszek M, Nguyen T, Flack KM, Lindsey JS. Two complementary routes to 7-substituted chlorins. Partial mimics of chlorophyll b. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:7736–7749. doi: 10.1021/jo701500d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arnaut LG. Design of porphyrin-based photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Adv Inorg Chem. 2011;63:167–233. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taniguchi M, Ptaszek M, McDowell BE, Boyle PD, Lindsey JS. Sparsely substituted chlorins as core constructs in chlorophyll analogue chemistry. Part 3: Spectral and structural properties. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:3850–3863. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pereira NAM, Laranjo M, Casalta-Lopes J, Serra AC, Piñeiro M, Pina J, de Melo JSS, Senge MO, Botelho MF, Martelo L, Burrows HD, Pinho e Melo TMVD. Platinum(II) ring fused chlorins as near-infrared emitting oxygen sensors and photodynamic agents. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2017;8:310–315. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ke XS, Zhao H, Zou X, Ning Y, Cheng X, Su H. Fine-tuning of b-substitution to modulate the lowest triplet excited states: A bioinspaired approach to design phosphorescent metalloporphyrinoids. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:10745–10752. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang E, Diers JR, Huang YY, Hamblin MR, Lindsey JS, Bocian DF, Holten D. Molecular electronic tuning of photosensitizers to enhance photodynamic therapy: synthetic dicyanobacteriochlorins as a case study. Photochem Photobiol. 2013;89:605–618. doi: 10.1111/php.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faure S, Stern C, Espinosa E, Douville J, Guilard R, Harvey PD. Triplet-triplet energy transfer controlled by the donor-acceptor distance in rigidly held palladium-containing cofacial bisporphyrins. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:3469–3481. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andréasson J, Kajanus J, Märtensson J, Albinsson B. Triplet energy transfer in porphyrin dimers: comparison between π- and σ-chromophore bridged systems. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9844–9845. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flamigni L, Armaroli N, Barigelletti F, Balzani V, Collin JP, Dalbavie JO, Heitz V, Sauvage JP. Photoinduced processes in dyads made of a porphyrin unit and a ruthenium complex. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:5936–5943. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flamigni L, Barigelletti F, Armaroli N, Collin J-P, Sauvage J-P, Williams JAG. Photoinduced processes in highly coupled multicomponent arrays based on ruthenium(II)bis(terpyridine) complex and porphyrin. Chem Eur J. 1998;4:1744–1754. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flamigni L, Barigelletti F, Armaroli N, Ventura B, Collin JP, Sauvage JP, Williams JAG. Triplet-triplet energy transfer between porphyrins linked via a ruthenium(II) bisterpyridine complex. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:661–667. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen BM, Lovassen BM, Simpson CK, Cummings SD, Dallinger RF, Hopkins MD. 1000-Fold enhancement of luminescence lifetimes via energy-transfer equilibration with T1 state of Zn(TPP) Inorg Chem. 2010;49:5777–5779. doi: 10.1021/ic100316s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asano-Someda M, Ichino T, Kaizu Y. Triplet-triplet intramolecular energy transfer in a covalently linked copper(II) porphyrin-free base porphyrin hybrid dimer: a time resolved ESR study. J Phys Chem A. 1997;101:4484–4490. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asano-Someda M, Kaizu Y. Highly efficient triplet-triplet intramolecular energy transfer and enhanced intersystem crossing in rigidly linked copper(II) porphyrin-free base porphyrin hybrid dimers. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:2303–2311. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toyama N, Asano-Someda M, Ichino T, Kaizu Y. Enhanced intersystem crossing in gable-type copper(II) porphyrin-free base porphyrin dimers: evidence of through-bond exchange interaction. J Phys Chem A. 2000;104:4857–4865. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colvin MT, Smeigh AL, Giacobbe EM, Conron SMM, Ricks AB, Wasielewski MR. Ultrafast intersystem crossing and spin dynamics of zinc meso-tetraphenylporphyrin covalently bound to stable radicals. J Phys Chem A. 2011;115:7538–7549. doi: 10.1021/jp2021006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petterson K, Kilsa K, Märtensson J, Albinsson B. Intersystem crossing versus electron transfer in porphyrin-based donor-bridge-acceptor systems: influence of a paramagnetic species. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6710–6719. doi: 10.1021/ja0370488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kinoshita Y, Yamamoto Y, Tamiaki H. Synthesis, structure, and optical and redox properties of chlorophyll derivatives directly coordination ruthenium bispyridine at the peripheral β-diketonate moiety. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:9275–9283. doi: 10.1021/ic400509q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pavri NP, Trudell ML. An efficient method for the synthesis of 3-arylpyrroles. J Org Chem. 1997;62:2649–2651. doi: 10.1021/jo961981u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cue BW, Jr, Chamberlain N. Pyluteorin derivatives II. Synthetic approach pyrrole ring substituted pyoluteorins. J Heterocyclic Chem. 1981;18:667–670. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryan A, Gehrold A, Perusitti R, Pintea M, Fazekas M, Locos OB, Blaikie F, Senge MO. Porphyrin dimers and arrays. Eur J Org Chem. 2011:5817–5844. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krayer M, Ptaszek M, Kim HJ, Meneely KR, Fan D, Secor K, Lindsey JS. Expanded scope of synthetic bacteriochlorins via improved acid catalysis conditions and diverse dihydrodipyrrin-acetals. J Org Chem. 2010;75:1016–1039. doi: 10.1021/jo9025572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mandal AK, Taniguchi M, Diers JR, Niedzwiedzki DM, Kirmaier C, Lindsey JS, Bocian DF, Holten D. Photophysical properties and electronic structure of porphyrins bearing zero to four meso-phenyl substituents: new insight into seemingly well understood tetrapyrroles. J Phys Chem A. 2016;120:9719–9731. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b09483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pineiro M, Carvalho AL, Pereira MM, Rocha Gonsalves AMd’A, Arnout LG, Formosinho SJ. Photoacoustic measurements of porphyrin triplet-state quantum yields and singlet-oxygen efficiencies. Chem Eur J. 1998;4:2290–2307. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kee HL, Kirmaier C, Tang Q, Diers JR, Muthiah C, Taniguchi M, Laha JK, Ptaszek M, Lindsey JS, Bocian DF, Holten D. Effect of substituents on synthetic analogues of chlorophylls. Part 1: synthesis, vibrational properties and excited-state decay characteristics. Photochem Photobiol. 2007;83:1110–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kasha M, Rawls HR, Ashraf El-Bayoumi M. The excitonModel in Molecular Spectroscopy. Pure Appl Chem. 1965;11:371–392. [Google Scholar]

- 57.For each bacteriochlorin dyad we observed a weak emission band on the short-wavelength edge of the emission spectrum. This band becomes a prominent in highly polar solvents (i.e. DMF, DMSO), in which the main emission band becomes severely reduced in intensity. An extensive purification did not affect the intensity of this band, and its consistent presence for each bacteriochlorin dyad (symmetrical and non-symmetrical) has led to the conclusion that this band is an intrinsic feature of bacteriochlorin dyads. The origin of this additional, weak band is unknown at this point.

- 58.Patel NJ, Chen Y, Joshi P, Pera P, Baumann H, Missert JR, Ohkubo K, Fukuzumi S, Nani RR, Schnermann MJ, Chen P, Zhu J, Kadish KM, Pandey RK. Effect of metallation on porphyrin-based bifunctional agents in tumor imaging and photodynamic therapy. Bioconjugate Chem. 2016;27:667–680. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kee HL, Diers RJ, Ptaszek M, Muthiah C, Fan D, Bocian DF, Lindsey JS, Culver JP, Holten D. Chlorin-bacteriochlorin energy-transfer dyads as prototypes for near-infrared molecular imaging probes: controlling charge-transfer and fluorescence properties in polar media. Photochem Photobiol. 2009;85:909–920. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuimova MK, Yahioglu G, Ogilby PR. Singlet oxygen in a cell: spatially dependent lifetimes and quenching rate constants. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:332–340. doi: 10.1021/ja807484b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Turro NJ, Ramamurthy V, Scaiano JC. Modern molecular photochemistry of organic molecules. University Science Books; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim D, Holten D, Gouterman M. Evidence from picosecond transient absorption and kinetic studies of charge-transfer states in copper(II) porphyrins. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:2793–2798. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gouterman M, Wagnière GH. Spectra of porphyrins part II. Four orbital model. J Mol Spec. 1963;11:108–127. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.