Abstract

Women with breast cancer frequently report distressing symptoms during and after treatment that can significantly erode quality of life (QOL). Symptom burden among women with breast cancer is of complex etiology and is likely influenced by disease, treatment, and environmental factors as well as individual genetic differences. The purpose of the present study was to examine the relationships between genetic polymorphisms within Neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor 1 (NTRK1), Neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor 2 (NTRK2), and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) and patient symptom burden of QOL, pain, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance before, during, and after treatment for breast cancer in a subset of participants (N = 51) in a randomized clinical trial of a novel symptom-management modality for women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Patients were recruited at the time of initial breast cancer diagnosis and completed all survey measures at the time of recruitment, after the initiation of treatment (surgery and/or chemotherapy), and then following treatment conclusion. Multiple linear regression analyses revealed significant associations between NTRK2 and COMT single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotype and symptom burden. Two COMT variants were associated with the specific symptoms of anxiety and QOL measures prior to the initiation of chemotherapy as well as pain interference and severity during and after treatment. Genotype at the NTRK2 SNP rs1212171 was associated with both sleep disturbance and fatigue. These findings, while exploratory, indicate that the genotypes of NTRK2 and COMT may contribute to relative risk for symptom burden during and shortly after the period of chemotherapy in women with early stage breast cancer.

Keywords: breast cancer, pain, depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, fatigue

Advances in breast cancer treatment have led to improvement in the rate of survival among women who are diagnosed in the early stages of disease (Jemal, Ward, & Thun, 2010). However, due to the cancer itself or its treatment, survival is often coupled with the presence of distressing symptoms that can negatively impact patient outcomes, including symptom burden and quality of life (QOL). Fatigue, mood disturbances such as depression and anxiety, sleep disturbance, and pain are among the most common adverse symptoms of breast cancer treatment (Bower & Ganz, 2013). While many women with breast cancer report cancer- and treatment-related symptoms, researchers have noted significant interindividual variability in symptom burden (Langford et al., 2016). Health status prior to diagnosis, disease stage, and treatment (surgical and nonsurgical) as well as environmental factors may contribute to the severity of cancer- and treatment-related symptoms (Belfer et al., 2013; Ganz, Rowland, Desmond, Meyerowitz, & Wyatt, 1998; G. E. Wyatt et al., 1998; G. K. Wyatt & Friedman, 1998), though the findings for these relationships have been inconsistent across studies (Gwede, Small, Munster, Andrykowski, & Jacobsen, 2008). More recently, researchers have found evidence that genetic factors contribute to differential symptom susceptibility when comparing those patients with extreme discordance in symptom phenotypes (Bower & Ganz, 2013; Saad et al., 2014; Schreiber, Kehlet, Belfer, & Edwards, 2014). Understanding the risk factors for increased symptom burden would allow providers to personalize treatment and guide patient expectations for the experience based on a patient’s individual risk for specific symptoms.

From a symptom-science perspective, there has been a significant research interest in characterizing cytokine-induced sickness behavior in patients with cancer. Studies have demonstrated associations between various inflammatory mediators and elevated levels of pain, depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbance (Cruz et al., 2015; Saad et al., 2014; Starkweather, Lyon, & Schubert, 2013). As a result, much of the research on genetic determinants of symptom burden in breast cancer has focused on polymorphisms within the genes encoding cytokines and other immune factors. Researchers have found, for example, an association between a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) within interleukin (IL)-10 (-1082 A/A) and mood disturbance (depression and anxiety) and fatigue severity in breast cancer patients (Bower & Ganz, 2013; Webber, Bennett, Goldstein, & Lloyd, 2014). When combined into a genetic risk index, SNPs within the promoter regions of the genes encoding three cytokines, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, were significantly associated with fatigue as well as depressive symptoms (Bower & Ganz, 2013). Moreover, Stephens et al. (2014) recently reported that the IL-1 receptor 2 SNP and haplotype of IL-10 A8 were associated with persistent pain in women with breast cancer. However, variations within cytokine and immune-related genes do not explain all of the individual differences in symptom burden. These prior studies suggest that a woman’s risk profile for specific cancer- and/or treatment-related symptoms may be under independent genetic control, so that fatigue, depression, and pain, for example, would all have separate risk profiles based on distinct sets of genes.

While these studies contribute to the understanding of the relationship of genetic variants with symptom burden in women with breast cancer, other genetic variants are also theoretically likely to contribute to the symptom variability. In particular, research has shown that polymorphisms in the genes encoding tyrosine receptor kinase A (TrkA) and tyrosine receptor kinase B (TrkB), NTRK1 and NTRK2, respectively, are significantly associated with individual differences in sensitivity and mood disorders (Martinowich & Lu, 2008). TrkA and TrkB play an important role in neurotrophic factor signaling, primarily by binding nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), respectively. Research has previously shown TrkA to regulate proinflammatory cytokine release; specifically, inflammatory stimuli upregulate the expression of TrkA on monocytes, which then bind NGF and subsequently reduce the production of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β (Prencipe et al., 2014). Variations within NTRK1, then, could affect the efficiency of this regulatory loop as well as the dynamics of the response, resulting in differential susceptibility to symptoms associated with increased inflammation. In addition, research has implicated alterations in BDNF–TrkB signaling within several brain structures in the pathophysiology of inflammation-induced depression (Zhang, Yao, & Hashimoto, 2016). Moreover, polymorphisms within NTRK2 could alter the dynamics of this signaling pathway and/or susceptibility to the inflammation-induced alterations in receptor function, thereby conveying risk for certain symptoms in the breast cancer population. Lastly, allelic variations of the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene, which is involved in the degradation of catecholamine neurotransmitters (i.e., dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine), have effects on mood, emotion processing, and perception of well-being, as well as pain sensitivity across a number of populations (Belfer & Segall, 2011; Wichers et al., 2008). Even with relatively small sample sizes, research has shown trends for patients with the Val158Met (rs4680) COMT polymorphism to have increased risk for persistent postsurgical pain and incidence of depressive symptoms (Hickey et al., 2011; Seib et al., 2016). Recent data also suggest an interaction effect of BDNF signaling and COMT on human cortical plasticity at the cellular and behavioral levels of analysis (Witte et al., 2012).

Considering the important roles of these three genes in regulating neurotrophin signaling, neuronal protection, and plasticity as well as the known connections between these signaling pathways and the inflammatory response, it is plausible that variation within these genes contributes to the severity of multiple symptoms, such as pain, fatigue, and mood disturbances, in women with breast cancer (see Figure 1). Thus, the purpose of the present study was to examine the relationships between genetic polymorphisms within NTRK1, NTRK2, and COMT and symptoms of pain, fatigue, depression/anxiety, and sleep disturbance before, during, and after chemotherapy treatment for early stage breast cancer.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of how genetic polymorphisms influence symptom burden during breast cancer treatment. Both breast cancer and breast cancer treatment have been shown to activate the immune response and subsequently increase the levels of circulating cytokines. In this way, expression of the neurotrophins’ nerve growth factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) are both modulated by proinflammatory cytokines. These two neurotrophins bind the TrkA and TrkB receptors encoded by the genes NTRK1 and NTRK2, respectively, and exert their downstream effects related to neuronal function and neural plasticity, specifically in relation to mood, sleep, and pain. We hypothesize that polymorphisms within the genes encoding TrkA and/or TrkB could alter the structure and/or function of the ligand-receptor relationship and thereby contribute to differential susceptibility to the behavioral effects of breast cancer and breast cancer treatment through their role in this pathway. Individual differences in activity of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), an enzyme responsible for the degradation of catecholamine neurotransmitters and encoded by COMT, have been implicated in a number of psychological outcomes, including mood alterations, psychoses, and pain susceptibility. Both BDNF and COMT play a role in modulating dopamine signaling, a process thought to play a role in the etiology of several symptoms following breast cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Material and Method

Design

The present study was a secondary analysis of data collected as part of a longitudinal randomized controlled trial that tested the effectiveness of cranial electrical microcurrent stimulation (CES) on the symptoms of depression, anxiety, fatigue, pain, and sleep disturbances in women with early stage breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Study procedures have been reported previously (Lyon et al., 2015). In the trial, participants were randomized into a treatment or sham group. The treatment group received a CES device that was preset to provide 100 μA modified square-wave biphasic stimulation on a 50% duty cycle at 0.5 Hz and to automatically turn off at the end of 1 hr. Sham devices distributed to participants in the sham group were indistinguishable from the actual CES devices except that the ear clip electrodes did not pass current. The participants completed questionnaires prior to initiating adjuvant chemotherapy (pretreatment/T1), at 7–8 weeks after initiation of chemotherapy (midtreatment/T2) and 1 week following the completion of chemotherapy (posttreatment/T3). As there were no significant differences in symptom severity or interference between those receiving CES and those in the sham condition in the parent study (i.e., CES did not affect patient symptom burden, data presented elsewhere; Lyon et al., 2015), we collapsed the current subjects/samples into one group regardless of CES condition for the following analysis.

Sample and Setting

Researchers for the parent study recruited a total of 168 women from a National Cancer Institute—designated cancer center affiliated with a major research university in the mid-Atlantic region and affiliated regional institutions. Participant inclusion criteria were as follows: women > 21 years of age; able to read, write, and understand English; confirmed diagnosis of Stages I–IIIA breast cancer; a performance score < 2 using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group criteria; and scheduled to receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients were excluded if they had previous chemotherapy, dementia, active psychosis, history of seizure disorder, any implanted electrical device, or had started a medication regimen for depression or other psychiatric condition within 30 days prior to enrollment. All methods and protocols were approved by the institutional review board for the university health system cancer center and affiliated institutions. The research team strictly adhered to informed consent procedures, and a member of the team obtained written informed consent from each study participant.

Procedures

Of the 168 women with early-stage breast cancer (Stages I–IIIA) participating in the parent study, a subgroup of 60 women gave permission for genetic analysis of specimens collected for the parent study. For the present study, we genotyped 51 patients with completed data sets to examine the relationships between selected SNPs and self-reported symptoms. Referring oncologists and nurses told patients who met the study criteria and were scheduled to begin chemotherapy about the study, and then research staff approached them. After obtaining written informed consent, research staff asked participants to complete questionnaires and have their blood drawn in a private research suite. Blood samples were collected by venipuncture or existing access device and the specimens were immediately transported to the laboratory, where genomic DNA was collected and stored for subsequent genotyping. Research staff gave participants incentives (a US$25 gift card to a local store that has both food and personal items for sale) at each data collection point. The current analysis is based on genomic DNA from blood samples collected at the first visit (pretreatment) only.

Instruments

Demographic, individual, disease-, and cancer-treatment-related variables

A comprehensive questionnaire and medical-record review was completed at baseline and at subsequent data points. Age, race/ethnicity, and body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) were assessed along with treatment variables (i.e., surgical intervention planned/completed and prescribed chemotherapy regimen). We entered all of these variables into the linear regression model as described below.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

The HADS (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) is a brief (14 item) self-report questionnaire developed to detect the presence and severity of both anxiety and depressive symptoms at the time of reporting. Because it was developed for use in medically ill patients, it does not rely upon somatic symptoms of depression and anxiety such as pain and weight loss but rather contains only cognitive symptoms of anxiety and depression. Participants rate (0–3) the severity of each symptom over the past 7-day period. Possible score on each of the two subscales of depression and anxiety is 0–21, and the possible total scale score is 0–42. The HADS has well-established reliability and validity for both depression and anxiety in women with breast cancer (Montazeri et al., 2001).

The Brief Pain Inventory–Short Form (BPI-SF)

The BPI-SF (Cleeland & Ryan, 1994) is a pain-assessment tool that has well-established reliability and validity for adult patients with no cognitive impairment in trajectory studies of cancer and its symptoms (Caraceni, 2001). The BPI-SF consists of 15 questions that measure pain location and intensity, pain treatment, treatment effectiveness, and functional interference from pain (Keller et al., 2004). The instrument assesses pain intensity at its “worst,” “least,” and “average” levels over the past week, as well as pain “now,” using a numerical rating scale from 0 = no pain to 10 = worst possible pain imaginable. Estimated time for completion of the BPI-SF is 5 min. We used patient rating of their “worst pain” from the BPI-SF as our measure of pain severity and the arithmetic mean of the 7 interference items as our measure of pain interference. In widespread testing, the Cronbach’s α reliability has ranged from .70 to .91.

The Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI)

The BFI (Mendoza et al., 1999) is a 9-item scale that taps into a single dimension of fatigue severity and the interference fatigue creates in daily life. The BFI is a clinically validated tool used to assess cancer-related fatigue and its impact on daily functioning. The BFI uses simple numeric rating scales from 0 to 10 that are easily understood. On the BFI, severe fatigue can be defined as a score of 7 or higher. The BFI has demonstrated excellent reliability in clinical trials, with Cronbach’s α reliability ranging from .82 to .97 (Mendoza et al., 1999).

The General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS)

The 21-item GSDS consists of items that evaluate various aspects of sleep disturbance (quality and quantity of sleep, sleep-onset latency, number of awakenings, excessive daytime sleepiness, and medication use) over the past week (Lee, McEnanay, & Weekes, 1999). Respondents rate items on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 7 (every day). Total score is a sum of the 21 items and has a possible range from 0 (no sleep disturbance) to 147 (extreme sleep disturbance). In a recent study of the symptoms of fatigue, sleep disturbance, depression, and pain in 191 cancer patients, the Cronbach’s α reliability for the GSDS was .82 (Miaskowski et al., 2006).

QOL measures

The functional assessment of cancer therapy for breast cancer (FACT-B; Brady et al., 1997) is a 44-item self-report instrument designed to measure multidimensional QOL in patients with breast cancer. The FACT-B consists of the FACT-General plus the Breast Cancer subscale, which complements the general scale with items specific to QOL in breast cancer.

Genotyping of SNPs

We evaluated the following genes for potential associations with symptom burden: NTRK1, NTRK2, and COMT. TrkA is a member of the Trk family of tyrosine kinase receptors for NGF and is encoded by NTRK1 (Chao, 2003). Research has shown TrkA function to a play a vital role in controlling rapid-eye-movement sleep in animal models (Takahashi & Krueger, 1999). Variation within the gene encoding TrkA has multiple phenotypic characteristics with hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathies (Smeyne et al., 1994). Congenital insensitivity to pain has been linked to the gene encoding for a NGF-specific tyrosine kinase receptor (Tuysuz et al., 2008), further linking neurotrophic factor signaling with pain processing and/or modulation.

NTRK2 is the gene encoding TrkB, the receptor with the highest binding affinity for BDNF signaling. BDNF is a secreted neurotrophic factor, known to be critical for numerous aspects of synaptic plasticity in the adult central nervous system (Cotman & Berchtold, 2002). BDNF promotes neuronal plasticity by binding to a receptor complex formed by TrkB, which has a known role in pain and a proposed role in manifestations of fatigue, anxiety, and depression (Chao, 2003; Chen et al., 2008).

Research has found associations between common SNPs in COMT and pain perception (Diatchenko et al., 2005; Zubieta et al., 2003). One of these, rs4680, is a nonsynonymous SNP associated with the Val158Met substitution, which has been linked to alterations in COMT enzymatic function as well as individual variation in psychological and pain-related phenotypes. The synonymous COMT SNP rs4818 has also been associated with risk for painful conditions.

We selected four SNPs (NTRK1, rs6336; NTRK2, rs1212171; and COMT, rs4818 and rs4680) for analysis in the present study based on these previous biochemical and genetic findings. In addition, we used the following criteria to select the highest priority SNPs within the candidate genes of interest so as to decrease the number of comparisons made in the small sample: (1) SNPs in exonic regions with a (2) known minor allele frequency greater than 5% and (3) prior associations to clinical outcomes in other populations. Peripheral blood samples were collected in Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) from all participants. Genomic DNA was isolated by QIAamp® DNA mini kit (QIAGEN, Tokyo, Japan), and the genotypes of SNPs were determined by direct sequencing (MACROGEN, Seoul, South Korea). We carried out polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) using the sense and antisense primers of each SNP under the following conditions: 40 cycles, each consisting of 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, and 1 cycle at 72°C for 5 min to extend the final reaction. The PCR products were sequenced by an ABI PRISM 3730XL analyzer (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). SeqManII software version 5.0 (DNASTAR, Madison, WI) was used to analyze the sequencing data.

Statistical Analyses

We used descriptive statistics to analyze sample demographic data and multiple linear regression analyses using an additive genetic model to explore the contributions of the candidate gene SNPs to symptom burden with each scale/measure as a separate dependent variable. In the first step, we entered biological predictors influential to health outcomes (age, gender, race, and BMI). For the evaluations completed at diagnosis (pretreatment/T1), the second step of the model consisted of genotype of each SNP. For measures completed following surgery and after initiation of chemotherapy (midtreatment/T2) and after the completion of the surgical and chemotherapy regimen (posttreatment/T3), the second step of the model consisted of both the surgery type and chemotherapy regimen prescribed. Given the lack of agreement within the literature as to whether surgery type and chemotherapy significantly affect symptom burden, we controlled for any potential influence by loading these variables together into the linear regression model. For these later time points, we loaded genotype at each SNP as the final step in the regression model. Although we loaded each SNP separately into each model, no symptoms were associated with multiple SNPs. In order to correct for multiple comparisons (total of four for the four individual SNPs evaluated), the adjusted p value necessary for significant associations is p ≤ .0125. Given the exploratory nature of the study and our desire not to dismiss associations that are approaching significance, we have presented findings, along with p values, using the uncorrected p value of .05. This approach allows for the most robust generation of testable hypotheses for future studies into the mechanisms underlying these associations.

Results

Genetic Variation and Sample Demographics

From the 60 samples that researchers collected in the original cohort, 51 were from patients who completed the outcome measures at all three time points and were successfully genotyped at four SNPs (rs1212171 [NTRK2], rs6336 [NTRK1], and rs4680 and rs4818 [COMT]). As shown in Table 1, we observed some heterogeneity in age, race, BMI, and surgical/chemotherapy regimen across participants; therefore, we loaded these factors into the regression model first to remove potential confounding effects and identify significant effects based on the amount of variance (R 2 change, F change, p change) explained by genotype alone.

Table 1.

Demographics of the Sample of Female Patients Undergoing Treatment for Early Stage Breast Cancer.

| Characteristic | Mean ± Standard Deviation, %, or n |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 51.9 ± 11.4 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 31 ± 11.0 |

| Race, % | |

| White (1) | 69 |

| Black or African American (2) | 27 |

| More than one race (3) | 4 |

| Surgery type, n | |

| Lumpectomy (1) | 8 |

| Excision (2) | 1 |

| Core biopsy (3) | 9 |

| Segmental biopsy (4) | 7 |

| Simple mastectomy (5) | 4 |

| Bilateral mastectomy (5) | 7 |

| Other (6) | 15 |

| Chemotherapy regimen, n | |

| None indicated (1) | 2 |

| AC (2) | 2 |

| NC (3) | 15 |

| AC followed by Taxane (4) | 21 |

| Other (5) | 11 |

Note. Parenthetical numbers next to nonlinear variables represent the values used in the linear regression model. AC = adjuvant chemotherapy; NC = neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

All SNPs that we investigated had call rates > 95% and were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium compared to the 1000 Genomes Project allele frequencies. We analyzed the SNPs using linear regression for each outcome measure of interest (pain severity [BPISev], pain interference [BPIInt], fatigue severity [BFISev], fatigue interference [BFIInt], sleep disturbance [GSDSTot], QOL [FACT-BTot], depression, and anxiety [HADSAnx]) at all three time points (pretreatment/T1, midtreatment/T2, and posttreatment/T3).

Genotypic Effects on Symptom Burden

Psychological and QOL measures

The COMT SNP rs4860 (Val158Met) was significantly associated with patient symptom burden prior to the initiation of surgery and/or chemotherapy. Patients with the A/A genotype at rs4680 reported more anxiety (HADSAnx; see Table 2 and Figure 2A) and reduced QOL (FACT-BTot, see Table 2 and Figure 2B) at baseline (T1), p < .05, compared to patients with G/G or A/G genotypes after correction for demographic confounders.

Table 2.

Associations Between COMT rs4680 Genotype and Anxiety and Quality of Life at the Time of Breast Cancer Diagnosis (T1).

| Model | Anxiety (HADS) | Quality of Life (FACT-B) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F Change | R2 Change | p Value | F Change | R2 Change | p Value | |

| Model 1—age, race, BMI | 6.282 | .286 | .001 | 3.321 | .175 | .028 |

| Model 1 + rs4680 genotype | 8.618 | .113 | .005 | 5.012 | .081 | .030 |

Note. BMI = body mass index; FACT-B = functional assessment of cancer therapy for breast cancer; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Figure 2.

Mean scores (+SEM) for (A) anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Anxiety subscale) and (B) quality of life (Functional Assessment of Cancer Treatment for Breast Cancer Scale) at Baseline (T1) by COMT single nucleotide polymorphism rs4680 genotype. *Significant difference (p < .05). Note. SEM = Standard Error of the Mean.

Genotypic variation accounted for ∼11% of the variance in anxiety and 8% of the variance in breast cancer-related QOL. No other associations were present at baseline between the SNPs and the measures assessed. After surgery and following initiation of chemotherapy (T2), only one QOL measure, sleep disturbance (GSDSTot), was significantly associated with genotype. The presence of the T allele at NTRK2 SNP rs1212171 was associated with an increase in sleep disturbance, with heterozygotes reporting moderate sleep disturbance and T/T homozygotes reporting the highest levels of sleep disturbance, after correcting for demographic variables as well as type of surgery and chemotherapy regimen, when compared with all C alleles carriers (see Table 3 and Figure 3, p < .05). We found no significant associations between genotype and psychological or QOL measures following surgery and chemotherapy (T3), all p > .05.

Table 3.

Association Between NTRK2 Genotype and Sleep Disturbance During Breast Cancer Treatment (T2).

| Model | Sleep Disturbance (GSDS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| F Change | R2 Change | p Value | |

| Model 1—age, race, BMI | 3.061 | .179 | .038 |

| Model 1 + surgery, chemotherapy | 1.121 | .044 | .336 |

| Model 2 + rs1212171 genotype | 12.479 | .188 | .001 |

Note. BMI = body mass index; GSDS = General Sleep Disturbance Scale.

Figure 3.

Mean scores (+SEM) for sleep disturbance during treatment for breast cancer (T2) by NTRK2 single nucleotide polymorphism rs1212171 genotype. *Significant differences by genotype (p < .05). GSDS = General Sleep Disturbance Scale. Note. SEM = Standard Error of the Mean.

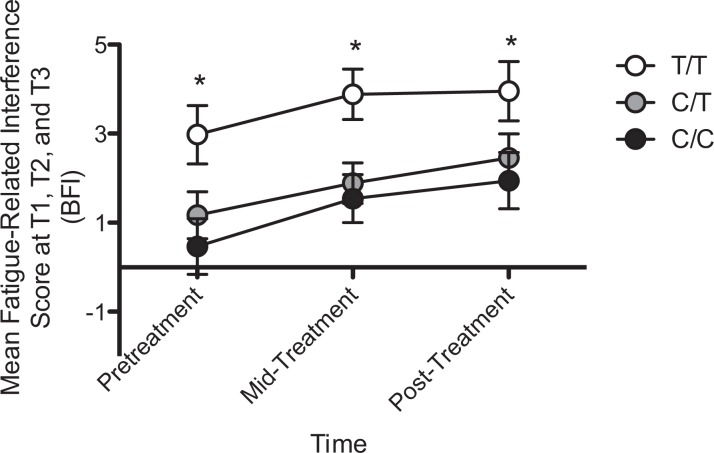

Fatigue

Patients homozygous for the T allele at rs1212171 within NTRK2 reported significantly more fatigue-related interference in their daily functioning (BFIInt) at all three time points, p < .05 (see Figure 4). Regression analysis confirmed a significant effect of genotype on BFIInt, with genotype explaining ∼9%, ∼15%, and ∼10% of the variance in BFIInt at T1, T2, and T3, respectively, all p < .05. The presence of the T allele at rs1212171 was also predictive of the severity of fatigue (BFISev) prior to treatment initiation, explaining ∼9% of the variance in reported fatigue severity (data not shown), but was not associated with fatigue during (T2) or after treatment was complete (T3). We identified no other genotype effects on fatigue, all p > .05.

Figure 4.

Mean scores (+SEM) for fatigue-related interference by genotype at single nucleotide polymorphism rs1212171 within NTRK2 at all three time points. *Significant differences by genotype (p < .05). Note. SEM = Standard Error of the Mean.

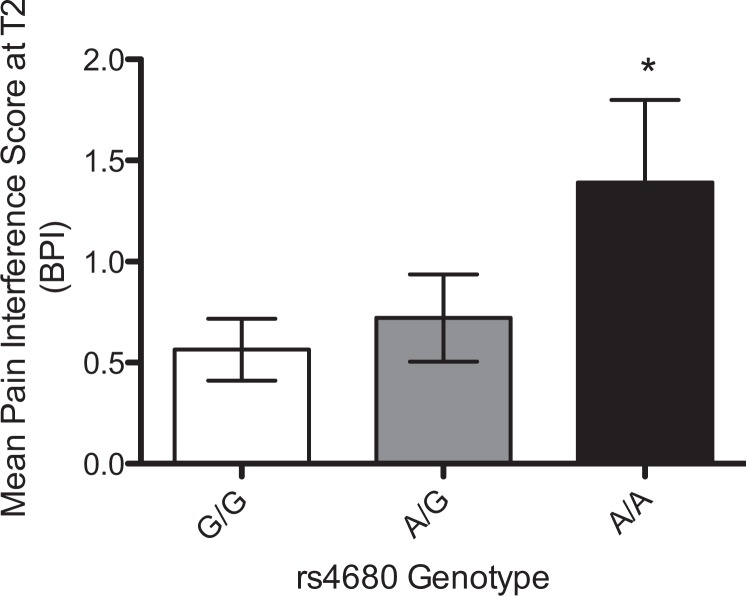

Pain

Two SNPs within COMT, rs4680 and rs4818, were associated with pain burden after surgery and initiation of chemotherapy for breast cancer (T2). Patients’ homozygous for the A allele at rs4680 reported significantly more pain-related interference in normal function (BPIInt, see Figure 5) during cancer treatment, with genotype accounting for ∼9% of the variance in patient reports. The synonymous SNP rs4818 in COMT was significantly associated with perceived severity and interference of pain following the completion of surgery and chemotherapy treatment (T3; BPISev and BPIInt, see Figure 6), with patients with the G/G genotype reporting significantly reduced pain severity and interference. Genotype explained ∼8% (p < .05) and ∼9% (p < .05) of the variance in pain-related interference and pain severity, respectively.

Figure 5.

Mean scores (+SEM) for pain interference (brief pain inventory [BPIInt]) following surgery and initiation of chemotherapy (T2) by genotype at single nucleotide polymorphism rs4680 within COMT. *Significant differences by genotype (p < .05). Note. SEM = Standard Error of the Mean.

Figure 6.

Mean scores (+SEM) for perceived pain (A) severity (brief pain inventory) and (B) interference following surgery and initiation of chemotherapy (T2) by genotype at the COMT single nucleotide polymorphism rs4818. *Significant differences by genotype (p < .05). Note. SEM = Standard Error of the Mean.

Discussion

In the present study, we have identified several novel associations among candidate gene polymorphisms and symptom burden in a cohort of breast cancer patients undergoing treatment. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer have significantly improved the life expectancy for patients. These lifesaving treatments, however, are associated with significant symptom burden that can have a negative impact on QOL. While prior findings have attempted to identify subgroups of patients with higher symptom burden, they have primarily defined these groups by demographic, psychosocial, and disease- and treatment-related factors (Miaskowski et al., 2006; Nagel, Schmidt, Strauss, & Katenkamp, 2001; Trask, 2004). The present findings add to this growing body of literature focused on identifying the factors that contribute to symptom susceptibility and burden in women with breast cancer. In addition, these findings point out different patterns of association of genetic variants and commonly experienced cancer symptoms. Although there were no associations between NTRK1 and symptom burden, both NTRK2 and COMT genotypes were associated with specific symptoms. Interestingly, the genes we evaluated were independently associated with different symptoms, suggesting that specific variants may underlie an individual’s symptom-susceptibility profile. Results of our test of linkage disequilibrium within the COMT SNPs (data not shown) in the present study suggested that these two SNPs are independently associated with pain and do not work together to increase risk further. We have previously proposed that multiple SNPs may act synergistically to influence multiple symptoms or to increase overall symptom burden, but the present findings suggest that genetic variation more likely contributes to individual symptom severity. Therefore, a panel of symptom-specific polymorphisms may serve as an important predictor of overall symptom burden and QOL in patients with early stage breast cancer.

Participants homozygous for the T allele at rs1212171 showed increased sleep disturbance and fatigue. This particular SNP occurs within the region of NTRK2 that regulates the expression of the TrkB receptor (Maussion et al., 2012), and it is likely that this polymorphism has an impact on the quality of BDNF–TrkB signaling. This relationship is of critical importance; BDNF and its TrkB receptor are intimately involved in the regulation of sleep. For example, injection of BDNF into the cortex of rodents increases cortical slow-wave activity (SWA), an electrophysiological correlate of sleep (Faraguna, Vyazovskiy, Nelson, Tononi, & Cirelli, 2008; Watson, Henson, Dorsey, & Frank, 2015). Moreover, sleep deprivation can increase BDNF mRNA expression and subsequent SWA, and in humans, an SNP that reduces BDNF release is associated with a decrease in Stage 4 nonrapid-eye-movement (NREM) sleep and lower NREM SWA (Watson et al., 2015). Research has shown that the activation of TrkB by BDNF increases with exercise and is reduced in models of fatigue (Chao, 2003; Chen et al., 2008). While the mechanism by which variation within NTRK2 affects symptom severity still remains to be fully elucidated, the present findings suggest that BDNF signaling holds potential as a novel therapeutic target for decreasing the negative impact of fatigue and improving patient symptom burden.

Pain is one of the most feared and prevalent symptoms among women with breast cancer, with 25–60% of women reporting persistent pain during the course of breast cancer survivorship (Andersen & Kehlet, 2011; Gartner et al., 2009). Although the etiology of pain associated with breast cancer is not well-understood, several studies have identified individual- and treatment-related risk factors, including younger age (Johannsen, Christensen, Zachariae, & Jensen, 2015; Mejdahl, Andersen, Gartner, Kroman, & Kehlet, 2013; Peukmann et al., 2009), poor physical function, axillary node dissection (Johannsen et al., 2015; Peukmann et al., 2009), postmenopausal endocrine treatment (Johannsen et al., 2015), and radiotherapy (Peukmann et al., 2009). Other studies have emphasized the psychosocial factors that predict pain after breast cancer treatment, including preoperative anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances (Miaskowski et al., 2012), distress (Mejdahl et al., 2013), and catastrophizing (Belfer et al., 2013). Patients report postoperative pain to be quite troubling, and it is very often resistant to pharmacological management (Basen-Engquist, Hughes, Perkins, Shinn, & Taylor, 2008). Identifying women with the highest genetic risk for developing persistent pain could inform postoperative pain expectations, analgesic need, and therapeutic interventions. Our findings suggest that two common SNPs within COMT, rs4818 and rs4680, are predictive of pain interference and/or severity during and after breast cancer surgery and chemotherapy. The presence of the minor A allele at rs4680 (Val158Met)—the genotype previously associated with a “worrier” phenotype of lower pain threshold, enhanced stress vulnerability, and lower COMT enzymatic activity—was associated with higher levels of pain interference but not with pain severity during breast cancer treatment (i.e., postsurgery and after initiation of chemotherapy). Interestingly, we did not observe this effect for persistent pain long after the cancer treatment regimen was completed. The association with interference but not severity could be related to the increased anxiety and enhanced stress vulnerability associated with the worrier genotype. Furthermore, the synonymous SNP rs4818, which does not result in a change in the amino acid sequence of the COMT enzyme, was significantly associated with pain interference and pain severity after treatment resolution. However, the presence of the G allele at this SNP, corresponding to higher enzymatic activity of COMT and reduced dopamine signaling in the prefrontal cortex, is associated with reduced cognitive performance (Diatchenko et al., 2005; Roussos, Giakoumaki, Pavlakis, & Bitsios, 2008). In our cohort of breast cancer patients, the presence of the G allele corresponded to reduced pain severity and reduced pain-related interference. Findings have been mixed regarding the influence of this particular SNP on pain outcomes. For example, in a recent study, Candiotti et al. (2014) failed to find a relationship between rs4818 genotype and pain in postsurgical patients but did show a significant association between variation at rs4818 and postsurgical emesis. Taken together, research suggests that A/A homozygotes exhibit enhanced cognition and memory performance as well as increased pain severity and pain interference. Future studies should evaluate whether this relationship is coincidental or the result of a shift in cognitive processing/modulation of pain. The present findings add to the knowledge base of genetic factors that influence symptom burden in women undergoing breast cancer treatment and suggest the need for prospective studies to test these relationships and plausible preventative therapies to mitigate symptom burden in this population.

Readers should consider several limitations in their interpretation of the present findings. First, as the present study was an adjunctive analysis of an existing data set, the sample size was limited to participants from the parent study who met inclusion criteria. While whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing would have been ideal for the purposes of hypothesis generation, our sample is not large enough for this type of analysis. As a result, while we have identified statistically significant relationships, these associations are by no means exhaustive. Second, given the small sample size and the overwhelming majority of patients reporting Caucasian ancestry, we were not able to fully account for ancestry using genetic markers. In an effort to mitigate the effect of ancestry, we loaded reported race (along with age and BMI) into the regression first to account for variability in the outcome measures resulting from those factors. While not ideal, this approach allowed us to isolate the effect of genotype apart from race. We also selected SNPs that had minor-allele frequencies that were above 5% in both Caucasian and African/African American populations when that information was available. Lastly, the present study does not explore the mechanism by which these polymorphisms convey susceptibility to symptoms, so follow-up studies using preclinical models (animal models, tissue culture, and stem cells) are essential to fully elucidate why genetic variation within these candidates alters symptom burden.

Conclusions

Data from this study suggest that common polymorphisms in NTRK2 and COMT, but not NTRK1, influence the severity of symptoms and symptom burden in patients undergoing treatment for breast cancer. Specifically, we found associations between specific SNP genotypes and higher anxiety (rs4860) at diagnosis and increased sleep disturbance, fatigue (rs1212171), and pain severity and interference (rs4680 and rs4818) during treatment. Despite our findings, it is possible that variation within NTRK1 may contribute to symptom burden to a lesser extent, and future studies should explore that possibility. Although the sample size was small, the results of the present study provide a basis for examining these relationships in larger samples and for beginning to test genotype-specific interventions among women at heightened risk of a more pronounced symptom burden.

As with other studies of genetic contributions to complex clinical outcomes, each gene or polymorphism may only explain a small amount of the variance in the behavior of interest, and many genes likely contribute. Previous studies have implicated other genetic polymorphisms in various aspects of symptom burden in women with breast cancer. For example, variation within the purinergic transporter P2RX7 gene is significantly associated with mood disturbance but not with pain or fatigue (Webber et al., 2014). Alternatively, specific SNPs in five separate potassium-channel genes are associated with mild pain (KCNA1, KCND2, KCNJ3, KCNJ6, and KCNK9), while three SNPs and one haplotype across distinct potassium-channel-encoding genes (KCND2, KCNJ3, KCNJ6, and KCNK9) have been linked with severe breast pain after breast cancer surgery (Langford et al., 2015).

Nurses and other health-care professionals play a significant role in providing symptom-management interventions for women with breast cancer. A more targeted approach to symptom management would help to ensure that these providers are able to deliver the most efficacious strategies to patients who are at highest risk. The findings of the present study and prior and future studies on the associations between specific genotypes and symptoms may be used to provide individualized symptom projections as well as guide development of genotype-specific symptom-management strategies (pharmacological, behavioral, etc.) for those most vulnerable. Future work in this area will provide insight into whether specific individualized interventions based on genotype can make a difference in reducing symptom burden and improving QOL for women with breast cancer.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. All of the authors have stated that no conflicts of interest exist.

Authors’ Contribution: Erin E. Young contributed to data acquisition, data analysis, and interpretation; drafted the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; and agrees to be held accountable for all aspects of work, ensuring integrity and accuracy. Debra Lynch Kelly contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, and interpretation; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; and agrees to be held accountable for all aspects of work, ensuring integrity and accuracy. Insop Shim contributed to conception, design, data acquisition; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; and agrees to be held accountable for all aspects of work, ensuring integrity and accuracy. Kyle M. Baumbauer contributed to data analysis and interpretation; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; and agrees to be held accountable for all aspects of work, ensuring integrity and accuracy. Angela Starkweather contributed to conception, design, and interpretation; drafted the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; and agrees to be held accountable for all aspects of work, ensuring integrity and accuracy. Debra E. Lyon contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, data analysis, and interpretation; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; and agrees to be held accountable for all aspects of work, ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and National Cancer Institute (R01CA127446; Lyon PI). Dr. Lyon (Jackson-Cook/Lyon; MPI; R01 NR012667) and Dr. Starkweather (R01 NR013932) are currently receiving grants.

References

- Andersen K. G., Kehlet H. (2011). Persistent pain after breast cancer treatment: A critical review of risk factors and strategies for prevention. Journal of Pain, 12, 725–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basen-Engquist K., Hughes D., Perkins H., Shinn E., Taylor C. C. (2008). Dimensions of physical activity and their relationship to physical and emotional symptoms in breast cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 2, 253–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfer I., Schreiber K. L., Shaffer J. R., Shnol H., Morando A., Englert D.…Bovbjerg D. H. (2013). Persistent postmastectomy pain in breast cancer survivors: Analysis of clinical, demographic and psychosocial factors. Journal of Pain, 14, 1185–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfer I., Segall S. (2011). COMT genetic variants and pain. Drugs Today, 47, 457–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower J. E., Ganz P. A. (2013). Cytokine genetic variations and fatigue among patients with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31, 1656–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady M. J., Cella D. F., Mo F., Bonomi A. E., Tulsky D. S., Lloyd S. R.…Shiomoto G. (1997). Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast quality-of-life instrument. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 15, 974–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candiotti K. A., Yang Z., Buric D., Arheart K., Zhang Y., Rodriguez Y.…Wang L. (2014). Catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphisms predict opioid consumption in postoperative pain. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 119, 1194–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraceni A. (2001). Evaluation and assessment of cancer pain and cancer pain treatment. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 45, 1067–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao M. V. (2003). Neurotrophins and their receptors: A convergence point for many signalling pathways. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4, 299–309. doi:10.1038/nrn1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Liang F. X., Moriya J., Yamakawa J., Sumino H., Kanda T., Takahashi T. (2008). Chronic fatigue syndrome and the central nervous system. Journal of International Medical Research, 36, 867–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland C. S., Ryan K. M. (1994). Pain assessment: Global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Annals, Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 23, 129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman C. W., Berchtold N. C. (2002). Exercise: A behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends in Neuroscience, 25, 295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz F. M., Munhoz B. A., Alves B. C., Gehrke F. S., Fonseca F. L., Kuniyoshi R. K.…Del Giglio A. (2015). Biomarkers of fatigue related to adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: Evaluation of plasma and lymphocyte expression. Clinical and Translational Medicine, 4, 4 doi:10.1186/s40169-015-0051-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diatchenko L., Slade G. D., Nackley A. G., Bhalang K., Sigurdsson A., Belfer I.…Maixner W. (2005). Genetic basis for individual variations in pain perception and the development of a chronic pain condition. Human Molecular Genetics, 14, 135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraguna U., Vyazovskiy V. V., Nelson A. B., Tononi G., Cirelli C. (2008). A causal role for brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the homeostatic regulation of sleep. Journal of Neuroscience, 28, 4088–4095. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5510-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz P. A., Rowland J. H., Desmond K., Meyerowitz B. E., Wyatt G. E. (1998). Life after breast cancer: Understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 16, 501–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner R., Jensen M. B., Neilsen J., Ewertz M., Kroman N., Kehlet H. (2009). Prevalence of and factors associated with persistent pain following breast cancer surgery. Journal of the American Medical Association, 302, 1985–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwede C. K., Small B. J., Munster P. N., Andrykowski M. A., Jacobsen P. B. (2008). Exploring the differential experience of breast cancer treatment-related symptoms: A cluster analytic approach. Supportive Care in Cancer, 16, 925–933. doi:10.1007/s00520-007-0364-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey O. T., Nugent N. F., Burke S. M., Hafeez P., Mudrakouski A. L., Shorten G. D. (2011). Persistent pain after mastectomy with reconstruction. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia, 23, 482–488. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2011.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A., Ward E., Thun M. (2010). Declining death rates reflect progress against cancer. PLoS One, 5, e9584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannsen M., Christensen S., Zachariae R., Jensen A. B. (2015). Socio-demographic, treatment-related and health behavior predictors of persistent pain 15 months and 7-9 years after surgery: A nationwide prospective study of women treated for primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 152, 645–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller S., Bann C. M., Dodd S. L., Schein J., Mendoza T. R., Cleeland C. S. (2004). Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clinical Journal of Pain, 20, 309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford D. J., Paul S. M., Cooper B., Kober K. M., Mastick J., Melisko M.…Miaskowski C. (2016). Comparison of subgroups of breast cancer patients on pain and co-occurring symptoms following chemotherapy. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24, 605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford D. J., Paul S. M., West C. M., Dunn L. B., Levine J. D., Kober K. M.…Aouizerat B. E. (2015). Variations in potassium channel genes are associated with distinct trajectories of persistent breast pain after breast cancer surgery. Pain, 156, 371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. A., McEnanay G., Weekes D. (1999). Gender differences in sleep patterns for early adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 24, 16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon D., Kelly D., Walter J., Bear H., Thacker L., Elswick R. K. (2015). Randomized sham controlled trial of cranial microcurrent stimulation for symptoms of depression, anxiety, pain, fatigue and sleep disturbances in women receiving chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. Springerplus, 4, 369 doi:10.1186/s40064-015-1151-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinowich K., Lu B. (2008). Interaction between BDNF and serotonin: Role in mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33, 73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maussion G., Yang J., Yerko V., Barker P., Mechawar N., Ernst C., Turecki G. (2012). Regulation of a truncated form of tropomysin-related kinase B (TrkB) by Hsa-miR-185* in frontal cortex of suicide completers. PLoS One, 7, e39301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejdahl M. K., Andersen K. G., Gartner R., Kroman N., Kehlet H. (2013). Persistent pain and sensory disturbances after treatment for breast cancer: Six year nationwide follow-up study. British Medical Journal, 346, fl865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza T. R., Wang X. S., Cleeland C. S., Morrissey M., Johnson B. A., Wendt J. K., Huber S. L. (1999). The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: Use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer, 85, 1186–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C., Cooper B. A., Paul S. M., Dodd M., Lee K., Aouizerat B. E.…Bank A. (2006). Subgroups of patients with cancer with different symptom experiences and quality-of-life outcomes: A cluster analysis. Oncology Nursing Forum, 33, E79–E89. doi:10.1188/06.ONF.E79-E89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C., Cooper B., Paul S. M., West C., Lanford D., Levine J. D.…Aouizerat B. E. (2012). Identification of patient subgroups and risk factors for persistent breast pain following breast cancer surgery. Journal of Pain, 13, 1172–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montazeri A., Jarvandi S., Haghighat S., Vahdani M., Sajadian A., Ebrahimi M., Haji-Mahmoodi M. (2001). Anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients before and after participation in a cancer support group. Patient Education and Counseling, 45, 195–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel G. C., Schmidt S., Strauss B. M., Katenkamp D. (2001). Quality of life in breast cancer patients: A cluster analytic approach. Empirically derived subgroups of the EORTC-QLQ BR 23—A clinically oriented assessment. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 68, 75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peukmann V., Ekholm O., Rasmussen N. K., Groenvold M., Christiansen P., Moller S.…Sjogren P. (2009). Chronic pain and other sequelae in long-term breast cancer survivors: Nationwide survey in Denmark. European Journal of Pain, 13, 478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prencipe G., Minnone G., Strippoli R., De Pasquale L., Petrini S., Caiello I.…Bracci-Laudiero L. (2014). Nerve growth factor downregulates inflammatory response in human monocytes through TrkA. Journal of Immunology, 192, 3345–3354. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1300825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussos P., Giakoumaki S. G., Pavlakis S., Bitsios P. (2008). Planning, decision-making, and the COMT rs4818 polymorphism in healthy males. Neuropsychologia, 46, 757–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad S., Dunn L. B., Koetters T., Dhruva A., Langford D. J., Merriman J. D.…Miaskowski C. (2014). Cytokine gene variations associated with subsyndromal depressive symptoms in patients with breast cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18, 397–404. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber K. L., Kehlet H., Belfer I., Edwards R. R. (2014). Predicting, preventing, and managing persistent pain after breast cancer surgery: The importance of psychosocial factors. Pain Management, 4, 445–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seib C., Whiteside E., Voisey J., Lee K., Alexander K., Humphreys J.…Anderson D. (2016). Stress, COMT polymorphisms, and depressive symptoms in older Australian women: An exploratory study. Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers, 20, 478–481. doi:10.1089/gtmb.2015.0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeyne R. J., Klein R., Schnapp A., Long L. K., Bryant S., Lewin A.…Barbacid M. (1994). Severe sensory and sympathetic neuropathies in mice carrying a disrupted Trk/NGF receptor gene. Nature, 368, 246–249. doi:10.1038/368246a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkweather A. R., Lyon D. E., Schubert C. M. (2013). Pain and inflammation in women with early-stage breast cancer prior to induction of chemotherapy. Biological Research for Nursing, 15, 234–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens K., Cooper B. A., West C., Paul S. M., Baggott C. R., Merriman J. D.…Aouizerat B. E. (2014). Associations between cytokine gene variations and severe persistent breast pain in women following breast cancer surgery. Journal of Pain, 15, 169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S., Krueger J. M. (1999). Nerve growth factor enhances sleep in rabbits. Neuroscience Letters, 264, 149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask P. C. (2004). Quality of life and emotional distress in advanced prostate cancer survivors undergoing chemotherapy. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2, 37 doi:10.1186/1477-7525-2-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuysuz B., Bayrakli F., DiLuna M. L., Bilguvar K., Bayri Y., Yalcinkaya C.…Gunel M. (2008). Novel NTRK1 mutations cause hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy Type IV: Demonstration of a founder mutation in the Turkish population. Neurogenetics, 9, 119–125. doi:10.1007/s10048-008-0121-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson A. J., Henson K., Dorsey S. G., Frank M. G. (2015). The truncated TrkB receptor influences mammalian sleep. American Journal of Physiology—Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 308, R199–R207. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00422.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber K., Bennett B. K., Goldstein D., Lloyd A. R. (2014). Genetic associations of fatigue and other symptom domains after breast cancer treatment: Results from a prospective cohort study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32, 9537. [Google Scholar]

- Wichers M., Aguilera M., Kenis G., Krabbendam L., Myin-Germeys I., Jacobs N.…van Os J. (2008). The catechol-O-methyl transferase Val158Met polymorphism and experience of reward in the flow of daily life. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33, 3030–3036. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte A. V., Kurten J., Jansen S., Schirmacher A., Brand E., Sommer J., Floel A. (2012). Interaction of BDNF and COMT polymorphisms on paired-associative stimulation-induced cortical plasticity. Journal of Neuroscience, 32, 4553–4561. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6010-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt G. E., Desmond K. A., Ganz P. A., Rowland J. H., Ashing-Giwa K., Meyerowitz B. E. (1998). Sexual functioning and intimacy in African American and White breast cancer survivors: A descriptive study. Womens Health, 4, 385–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt G. K., Friedman L. L. (1998). Physical and psychosocial outcomes of midlife and older women following surgery and adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 25, 761–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. C., Yao W., Hashimoto K. (2016). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)—TrkB signaling in inflammation-related depression and potential therapeutic targets. Current Neuropharmacology, 14, 721–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond A. S., Snaith R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta J. K., Heitzeg M. M., Smith Y. R., Bueller J. A., Xu K., Xu Y.…Goldman D. (2003). COMT val158met genotype affects mu-opioid neurotransmitter responses to a pain stressor. Science, 299, 1240–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]