Summary

In C. elegans embryos, transcriptional repression in germline blastomeres requires PIE-1 protein. Germline blastomere-specific localization of PIE-1 depends, in part, upon regulated degradation of PIE-1 in somatic cells. We and others have shown that the temporal and spatial regulation of PIE-1 degradation is controlled by translation of the substrate-binding subunit, ZIF-1, of an E3 ligase. We now show that ZIF-1 expression in embryos is regulated by five maternally-supplied RNA-binding proteins. POS-1, MEX-3, and SPN-4 function as repressors of ZIF-1 expression, whereas MEX-5 and MEX-6 antagonize this repression. All five proteins bind directly to the zif-1 3′ UTR in vitro. We show that, in vivo, POS-1 and MEX-5/6 have antagonistic roles in ZIF-1 expression. In vitro, they bind to a common region of the zif-1 3′ UTR, with MEX-5 binding impeding that by POS-1. The region of the zif-1 3′ UTR bound by MEX-5/6 also partially overlaps with that bound by MEX-3, consistent with their antagonistic functions on ZIF-1 expression in vivo. Whereas both MEX-3 and SPN-4 repress ZIF-1 expression, neither protein alone appears to be sufficient, suggesting that they function together in ZIF-1 repression. We propose that MEX-3 and SPN-4 repress ZIF-1 expression exclusively in 1- and 2-cell embryos, the only period during embryogenesis when these two proteins co-localize. As the embryo divides, ZIF-1 continues to be repressed in germline blastomeres by POS-1, a germline blastomere-specific protein. MEX-5/6 antagonize repression by POS-1 and MEX-3, enabling ZIF-1 expression in somatic blastomeres. We propose that ZIF-1 expression results from a net summation of complex positive and negative translational regulation by 3′ UTR-binding proteins, with expression in a specific blastomere dependent upon the precise combination of these proteins in that cell.

Keywords: zif-1, translational repression, C. elegans, embryos, germline, POS-1, MEX-5/6, MEX-3, SPN-4, PIE-1

Introduction

Beginning with the zygote, P0, a series of four asymmetric divisions specifies P4, the single founder blastomere for the entire germline in C. elegans (Strome, 2005). Each of these divisions generates a smaller germline precursor (P1 through P4, termed the P lineage) and a larger somatic sister cell (Figure 1A). P4 divides symmetrically to generate Z2 and Z3, which go on to generate the entire germline post-embryonically. All P lineage germline blastomeres are transcriptionally repressed, a defining characteristic of primordial germ cells (Nakamura and Seydoux, 2008; Seydoux and Fire, 1994). Their somatic sisters, however, undergo rapid transcriptional activation and lineage-specific differentiation, demanding rapid reversibility for any repressive mechanism operating in the P lineage (Seydoux and Fire, 1994).

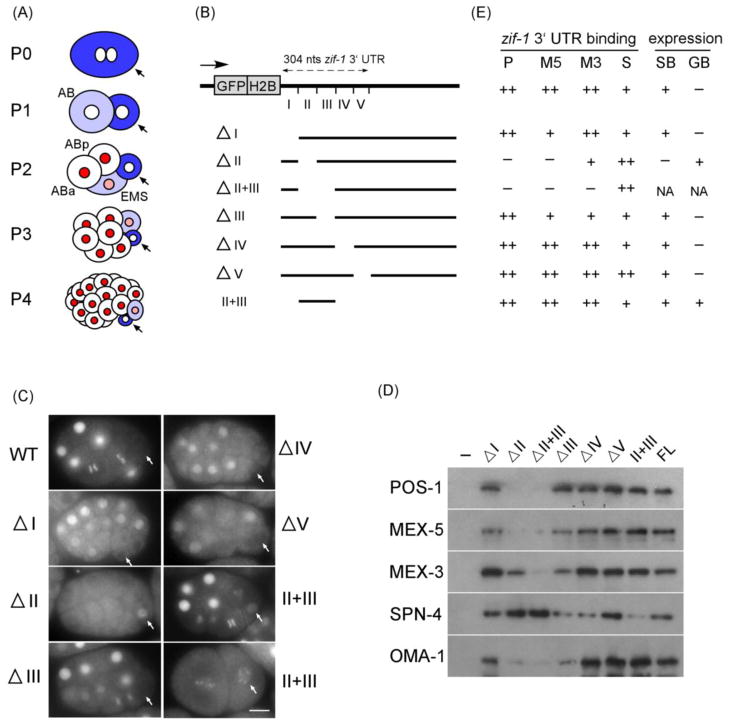

Figure 1. In vitro and in vivo analyses show importance of nucleotides 64–123 of the zif-1 3′ UTR.

(A) Sequential staging of early C. elegans embryos as determined by the P lineage blastomere (arrows). Blue: PIE-1 localization to the germline blastomere (dark blue), compared to its somatic sister (light blue). Red: expression of GFP::H2Bzif-1. Names of selected blastomeres are indicated. Arrows: germline blastomeres. (B) Schematic of the zif-1 3′ UTR, the five ~60nt subregions, and the deletion constructs utilized. (C) Representative fluorescence micrographs of embryos expressing GFP::H2B reporters under the control of the indicated zif-1 3′ UTR. Bar:10 μM. (D) In vitro RNA pulldowns using the indicated purified MBP-tagged protein and various forms of the zif-1 3′ UTR RNAs as shown in (B). After pulldown of RNA, protein bound to the RNA was assayed by Western blot using anti-MBP antibodies. The amount of SPN-4 pulled down appears to increase slightly with RNAs missing region II or V. We do not know the significance of this observation. FL: full length (304 nt). -: no RNA. (E) Summary of results in (C) and (D). P: POS-1; M5: MEX-5; M3: MEX-3; S: SPN-4; SB: somatic blastomere; GB: germline blastomere; NA: not analyzed due to derepression in oocytes.

Transcriptional repression in the C. elegans germline precursors requires at least two classes of maternally-supplied proteins. In P0 and P1, two closely-related and functionally redundant CCCH tandem zinc finger proteins, OMA-1 and OMA-2, globally repress transcription initiation by sequestering TAF-4, a critical component of the RNA pol II preinitiation complex, in the cytoplasm (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2008). In P2–P4, PIE-1, another CCCH tandem zinc finger protein, globally represses transcription by inhibiting both initiation and elongation phases of transcription (Batchelder et al., 1999; Ghosh and Seydoux, 2008; Seydoux and Dunn, 1997; Zhang et al., 2003). OMA-1, OMA-2, and PIE-1 proteins are all expressed from maternally-supplied mRNAs and are first detected in developing oocytes (Detwiler et al., 2001; Mello et al., 1996). OMA-1 and OMA-2 are degraded soon after the first mitotic division and are not detected in subsequent P lineage blastomeres (Detwiler et al., 2001; Lin, 2003). Degradation requires phosphorylation of the OMA proteins by at least two kinases, one of which, the DYRK2-type kinase MBK-2, is developmentally activated in newly-fertilized one-cell embryos (Cheng et al., 2009; Nishi and Lin, 2005; Shirayama et al., 2006; Stitzel et al., 2006). PIE-1 is segregated preferentially to the germline blastomere at each P lineage division (Mello et al., 1996). Global transcriptional repression by both OMA and PIE-1 is a robust but readily reversible way to transcriptionally silence the germline precursors, while maintaining the chromatin primed for transcriptional activation in the somatic sisters (Schaner et al., 2003).

The germline blastomere specific localization of PIE-1 is the result of selective enrichment towards the presumptive germline blastomere prior to division, coupled with selective degradation of any PIE-1 remaining in the somatic blastomeres following division (Reese et al., 2000). Degradation of PIE-1 in somatic cells is initiated by a CUL-2 containing E3 ligase (DeRenzo et al., 2003). The substrate-binding subunit of this E3 ligase, ZIF-1, binds PIE-1 via the first of the two CCCH zinc fingers found in PIE-1 (DeRenzo et al., 2003). GFP fused to the first zinc finger of PIE-1 (GFP::PIE-1 ZF1) functions as a reporter for PIE-1 degradation and undergoes ZIF-1-dependent degradation specifically in somatic blastomeres (Reese et al., 2000). We showed recently that the spatial and temporal regulation of this E3 ligase activity is controlled at the level of zif-1 translation (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2010). In C. elegans, correct spatio-temporal expression of almost all maternally-supplied transcripts is regulated post-transcriptionally via the 3′ UTR (Merritt et al., 2008). Using a translational reporter containing the zif-1 3′ UTR, we showed that zif-1 is translated in somatic cells, where PIE-1 is degraded, but not in oocytes or germline blastomeres, where PIE-1 levels are normally maintained.

We recently showed that OMA-1 and 2 bind to the zif-1 3′ UTR and, in a SPN-2 dependent manner, repress translation of zif-1 in oocytes (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2010; Li et al., 2009). This repression is relieved by phosphorylation of OMA-1 and −2 by MBK-2 (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2010). OMA proteins are phosphorylated by MBK-2 soon after completion of meiosis II, and therefore it is unlikely that they are responsible for the continuing repression of zif-1 translation in 1-cell embryos. It is not known how zif-1 translation remains repressed in 1- and 2-cell embryos, and is asymmetrically activated only in somatic blastomeres at the 4-cell stage. Many maternally-supplied key regulators of early embryonic patterning identified through forward genetic screens turned out to be proteins with RNA-binding motifs, highlighting the critical importance of translational control in early embryogenesis. Most of these RNA-binding proteins are asymmetrically localized to one or a few blastomeres. For example, POS-1, MEX-1, and SPN-4 are localized primarily to germline blastomeres (Guedes and Priess, 1997; Ogura et al., 2003; Tabara et al., 1999), whereas MEX-3, MEX-5, and MEX-6 are localized primarily to somatic blastomeres (Draper et al., 1996; Schubert et al., 2000). POS-1, MEX-1, MEX-5, and MEX-6, like PIE-1, all contain tandem CCCH zinc-finger RNA-binding motifs, and all are targets of the ZIF-1 containing E3 ligase (DeRenzo et al., 2003; Guedes and Priess, 1997; Mello et al., 1996; Reese et al., 2000; Schubert et al., 2000; Tabara et al., 1999). ZIF-1-dependent degradation in somatic blastomeres contributes to the restricted localization pattern of these proteins. MEX-5/6 are the only ZIF-1 substrates with an expression pattern that coincides both temporally and spatially with ZIF-1 activity. Despite being ZIF-1 substrates, MEX-5/6 have been shown to be required for ZIF-1-dependent degradation through an unknown mechanism (DeRenzo et al., 2003). OMA-1 and −2, although containing tandem CCCH zinc fingers, are not degraded via a ZIF-1-dependent mechanism (DeRenzo et al., 2003; Detwiler et al., 2001).

In this study, we investigate spatial and temporal control of ZIF-1 expression in the early embryo. We show that the somatic cell-specific translation pattern of zif-1 is a result of both net positive regulation in soma and repression in germline blastomeres. POS-1, MEX-3, and SPN-4 negatively regulate, whereas MEX-5 and MEX-6 positively regulate the expression of zif-1. All five proteins can bind to the zif-1 3′ UTR in vitro, suggesting direct regulation. POS-1, MEX-3, MEX-5, and MEX-6 share partially overlapping binding sites on the zif-1 3′ UTR and have antagonistic roles in zif-1 expression. We propose that the precise combinatorial expression of these five RNA-binding proteins determines whether the zif-1 transcript is translated in a particular blastomere.

Results

Nucleotides 64–123 of the zif-1 3′ UTR are required for repression in germline blastomeres and expression in somatic blastomeres

To investigate the mechanism by which the temporal and spatial expression pattern of zif-1 is regulated in embryos, we performed deletion analyses of the zif-1 3′ UTR in vivo. The zif-1 3′ UTR (304 nucleotides) was arbitrarily divided into five approximately 60 nucleotide regions (I–V, Figures 1B and Suppl Figure S1; (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2010)). GFP::H2B reporters driven by the zif-1 3′ UTR with each of these five regions individually deleted were generated, and the expression pattern in transgenic embryos was analyzed. No change in GFP::H2B expression was detected with any of the zif-1 3′ UTR single region deletion reporters, with the exception of Region II deletion (ΔII), which lacks nucleotides 64–123 (Figure 1C and 1E, n>100 for each transgene). This GFP reporter will be referred to as GFP::H2Bzif-1ΔII. GFP::H2Bzif-1ΔII exhibited nuclear GFP in germline blastomeres P3 and P4, and no GFP in somatic blastomeres, a highly noteworthy expression pattern as it is reciprocal to what is observed in wildtype embryos (Figure 1C and 1E, n>200). This result suggests (1) that somatic blastomere-specific expression of GFP::H2Bzif-1 is due to both negative regulation in germline blastomeres and positive regulation in somatic blastomeres, and (2) that Region II of the zif-1 3′ UTR mediates binding by both negative and positive regulators of ZIF-1 expression.

POS-1 represses and MEX-5/MEX-6 promote expression of zif-1, all via binding to nucleotides 64–123 of the zif-1 3′ UTR

To identify RNA-binding protein(s) that bind to zif-1 3′ UTR Region II and regulate spatial and temporal expression of ZIF-1, we directly tested RNA-binding proteins known to play key functional roles in early embryos, including POS-1, SPN-4, MEX-3, MEX-5, PIE-1, and MEX-1 (Draper et al., 1996; Guedes and Priess, 1997; Mello et al., 1992; Ogura et al., 2003; Schubert et al., 2000; Tabara et al., 1999). Biotinylated single-stranded zif-1 3′ UTR RNA was incubated with bacterially-expressed MBP-fused test proteins. RNA, along with associated proteins, was pulled down using streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads. MBP-fused protein pulled down with the RNA was analyzed by western blots using an anti-MBP antibody. We found that POS-1, SPN-4, MEX-3, and MEX-5 all bound to the full-length zif-1 3′ UTR in a sense strand-specific manner (Figure 1D, 1E, and data not shown). No specific binding was detected with PIE-1 or MEX-1 (data not shown). We also performed RNA pull-downs with RNAs corresponding to the zif-1 3′UTR with the five arbitrarily-defined regions deleted, either individually or in combination. We observed that binding by both POS-1 and MEX-5 was dramatically reduced if RNA with Region II deleted was used in the pull down. Individual deletion of any other region had minor or no effect upon POS-1 or MEX-5 binding (Figure 1D and 1E).

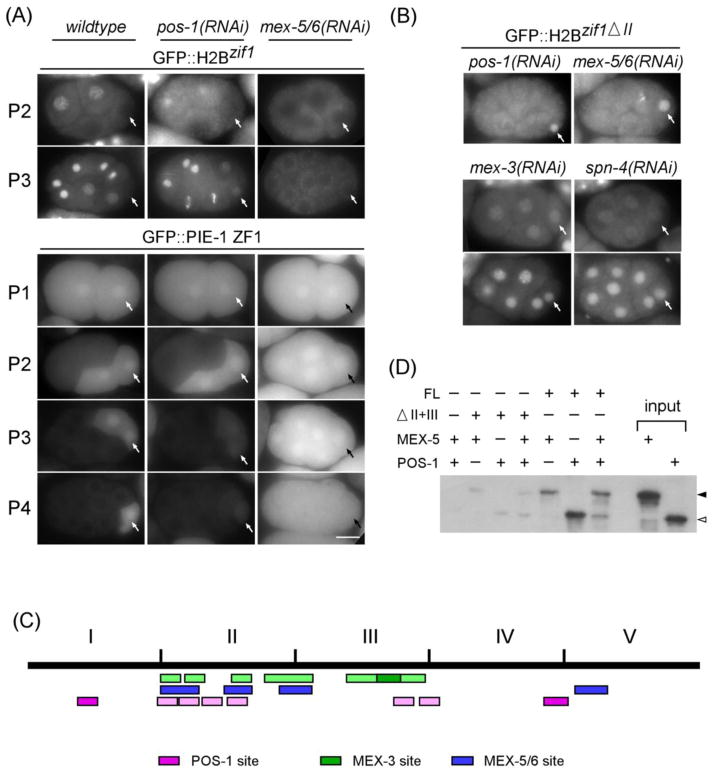

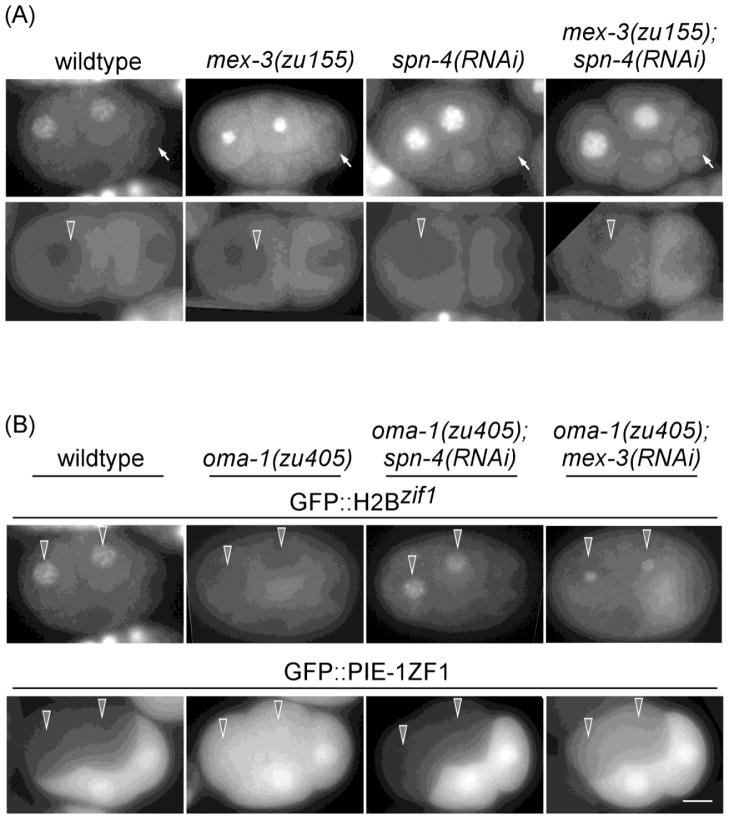

To determine whether POS-1 and/or MEX-5 regulate expression of ZIF-1, we depleted pos-1, or mex-5 and mex-6, by RNAi in the transgenic strain expressing GFP::H2Bzif-1 (Figure 2A). Depletion of pos-1 by RNAi resulted in derepression of GFP::H2Bzif-1 in germline blastomeres, which can be detected, albeit weakly, as early as P2 (20% embryos scored positive, n=40), and clearly in P3 (100% embryos scored positive, n=55). MEX-5 and MEX-6 share high sequence similarity, exhibit identical expression patterns, and have partially redundant functions in vivo, which suggests that they are likely to bind to the same RNA targets. Simultaneous depletion of mex-5 and mex-6, either by RNAi or genetic mutation [mex-5(zu199);mex-6(pk440)], resulted in a complete loss of GFP::H2Bzif-1 in embryos (100%, n=120 and 300, respectively). We also observed abnormal persistence of GFP::PIE-1 ZF1 in mex-5/6(RNAi) embryos (100%, n=90), and precocious degradation in pos-1(RNAi) embryos (100% embryos with a reduced GFP in P4, n=166) (Figure 2A), phenotypes previously reported for mex-5/6(−) and pos-1(−) mutant embryos (DeRenzo et al., 2003; Tabara et al., 1999). The phenotypes generated by either pos-1(RNAi) or mex-5/6(RNAi), with respect to GFP::H2Bzif-1 expression, are dependent on Region II of the zif-1 3′ UTR, as depletion of pos-1 or mex-5/6 resulted in no change in the expression of GFP::H2Bzif-1ΔII (n>50 for each RNAi, Figure 2B). Taken together, these results support a model whereby POS-1 negatively regulates, and MEX-5/6 positively regulate, the expression of ZIF-1, both via direct binding to Region II of the zif-1 3′ UTR.

Figure 2. POS-1, MEX-3, and SPN-4 repress whereas MEX-5/6 promote ZIF-1 expression in vivo.

(A) Fluorescence micrographs of staged embryos, indicated on the left by the germline blastomere (arrows), expressing GFP::H2Bzif-1 (top panels) or GFP::PIE-1 ZF1 (bottom panels) in wildtype, pos-1(RNAi), and mex-5/6(RNAi) backgrounds. Bar:10 μM. (B) Embryos expressing GFP::H2Bzif-1ΔII in pos-1(RNAi), mex-5/6(RNAi), mex-3(RNAi), and spn-4(RNAi) backgrounds. Both 4-cell and 8-cell embryos are shown for mex-3(RNAi), and spn-4(RNAi). (C) Schematic of putative binding sites for POS-1 (pink, 5′ UAU2–3RDN1–3G 3′), MEX-3 (green, 5′ (A/G/U)(G/U)AGN(0–8)U(U/A/C)UA 3′) and MEX-5/6 (blue, minimum 6 U per 8-nucleotide stretch) on the five regions of the zif-1 3′ UTR {Farley, 2008 #240; Pagano, 2009 #241; Pagano, 2007 #116}. Sequences that deviate by one nucleotide from the published optimal POS-1- and MEX-3-binding sites are indicated in lighter pink and lighter green, respectively. (D) POS-1 and MEX-5/6 binding to the zif-1 3′ UTR in vitro is antagonistic. In vitro RNA pulldowns using MEX-5 (arrow head), POS-1 (open arrowhead), or both, and indicated forms of the zif-1 3′ UTR RNAs were performed as in Figure 1D.

Depletion of pos-1 or mex-5/6 results in embryos with altered polarity, which could indirectly affect the expression of GFP::H2Bzif-1. Ideally, one would generate reporters with the zif-1 3′ UTR mutated for POS-1 binding sites or MEX-5 binding sites and assay their expression in embryos. The preferred binding sequences for the zinc fingers of POS-1 and MEX-5 in vitro have been investigated using electrophoretic mobility shift (EMSA) and fluorescence polarization (FP) assays (Farley et al., 2008; Pagano et al., 2007). Examination of the zif-1 3′ UTR identified four likely binding sites for POS-1 in Region II. However, three overlap with putative binding sites for MEX-5 (Figure 2C and Suppl Figure S1), precluding conclusive mutational analyses.

The overlapping putative POS-1 and MEX-5/6 binding sites within Region II of the zif-1 3′ UTR suggested that these proteins might have antagonistic functions in zif-1 expression in cells where POS-1 and MEX-5/6 co-localize. We tested therefore whether POS-1 and MEX-5/6 binding to the zif-1 3′ UTR in vitro is antagonistic. The biotinylated zif-1 3′ UTR RNA efficiently pulled down POS-1 or MEX-5 in the in vitro binding assay when either protein was presented alone. However, when both MEX-5 and POS-1 were presented simultaneously, MEX-5 was preferentially pulled down at the expense of POS-1 (Figure 2D). This result argues that MEX-5 binding to the zif-1 3′ UTR is preferred over POS-1 binding, and that MEX-5 binding impedes POS-1 binding. All together, our results support an antagonistic function between POS-1 and MEX-5 in the expression of ZIF-1 in vivo. In addition, they provide an explanation for how expression of MEX-5/6 could overcome the repressive function of POS-1 in somatic blastomeres newly separated from germline blastomeres.

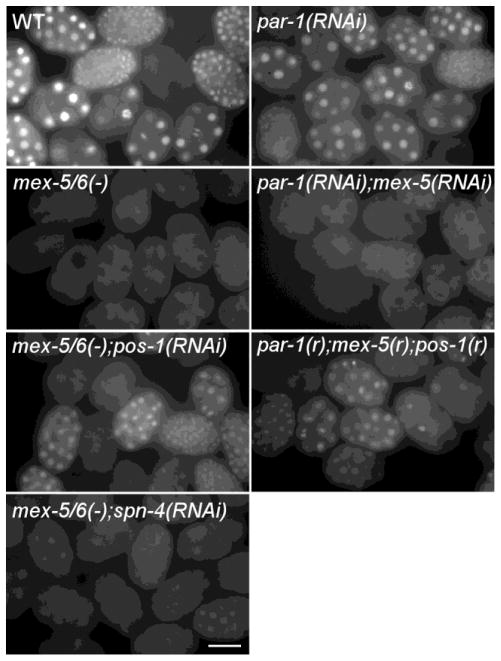

Two distinct functions for MEX-5 and MEX-6 in promoting zif-1 translation in somatic blastomeres

In mex-5(zu199);mex-6(pk440) mutant embryos, many proteins that are normally localized to the germline blastomeres, such as POS-1, have been shown to be uniformly distributed throughout the embryo (Schubert et al., 2000). Uniform distribution of POS-1, a repressor for zif-1 expression, could account for, or contribute to, the loss of GFP::H2Bzif-1 expression in mex-5(zu199);mex-6(pk440) embryos. Indeed, depletion of pos-1 by RNAi in mex-5(zu199);mex-6(pk440) embryos results in the expression of GFP::H2Bzif-1 in all cells in embryos at the 4-cell stage and older (100%, n>200; Figure 3). This result suggests that ectopic POS-1 accounts for most, if not all, of the loss of zif-1 expression in mex-5/6(−) embryos. In addition, it suggests that MEX-5/6 are not absolutely required for ZIF-1 expression when POS-1 is absent. In wildtype embryos, MEX-5 and MEX-6 levels are low in germline blastomeres due to the germline-blastomere-specific serine/threonine kinase, PAR-1. In par-1(RNAi) embryos, MEX-5 and MEX-6 are present at high levels in all early blastomeres (Schubert et al., 2000), and ZIF-1-dependent degradation of CCCH finger-containing proteins is detected in all cells (DeRenzo et al., 2003). We observed uniform distribution of GFP::H2Bzif-1 in par-1(RNAi) embryos that is dependent on MEX-5/6 activity. While GFP::H2Bzif-1 is not expressed in par-1(RNAi);mex-5(RNAi) embryos (0%, n>200), it is expressed when pos-1 is also depleted (100% embryos 4-cell and older, n>200; Figure 3). Taken together, our results demonstrate two distinct functions for MEX-5 and MEX-6 as positive regulators of zif-1 expression. First, MEX-5 and MEX-6 restrict the repressor POS-1 to germline blastomeres, releasing repression in somatic blastomeres. Second, in cells where MEX-5, MEX-6, and POS-1 co-localize, MEX-5/6 compete with POS-1 for overlapping binding sites on the zif-1 3′ UTR, antagonizing a POS-1 repressive effect.

Figure 3. MEX-5/6 positively regulate zif-1 expression in embryos by antagonizing repression by POS-1.

Fluorescence micrographs of groups of embryos expressing GFP::H2Bzif-1 in the indicated genetic backgrounds. Depletion of pos-1 suppresses the GFP::H2Bzif-1 defect in mex-5(zu199) ;mex-6(pk440) [mex-5/6(−)] and par-1(RNAi);mex-5(RNAi) embryos. In the bottom right hand panel, (RNAi) was abbreviated to (r) due to space limitation. Bar: 30μM.

MEX-3 and SPN-4 bind to the zif-1 3′ UTR and repress zif-1 translation in embryos

The above results demonstrate that MEX-5/6 are not absolutely required for the expression of zif-1 in somatic blastomeres. However, a GFP reporter regulated by the zif-1 3′ UTR lacking Region II (GFP::H2Bzif-1 Δ II), and therefore independent of POS-1 and MEX-5/6 regulation (Figures 1C and 2B), is nonetheless repressed in somatic blastomeres. This observation suggests one or more additional RNA-binding proteins that repress expression of zif-1 in somatic blastomeres through regions outside of Region II in the 3′ UTR. Because POS-1 accounts for most, if not all repression in mex-5(zu199);mex-6(pk440) embryos, this hypothetical RNA binding protein(s) is expected to be absent or inactive in mex-5(zu199);mex-6(pk440) embryos. Indeed, through RNA pulldown experiments we have identified two other proteins that exhibit specific binding to the zif-1 3′UTR: MEX-3 and SPN-4 (Figure 1D and 1E). MEX-3 binds to Regions II and III of the zif-1 3′ UTR. Deleting Region II or III alone results in a modest reduction whereas deleting both Region II and III results in a dramatic reduction in MEX-3 binding to the zif-1 3′ UTR. It has been shown previously that MEX-3 expression is abolished in mex-5(zu199);mex-6(pk440) mutant embryos (Schubert et al., 2000), making it a likely candidate for this predicted RNA-binding protein. SPN-4, on the other hand, although demonstrating zif-1 3′ UTR sense strand specificity, exhibited less sequence-specificity in its binding. SPN-4 binding was reduced, but not abolished, after pulldown of RNAs corresponding to the zif-1 3′ UTR deleted of either regions III or IV. Most dramatically, depletion of either mex-3 or spn-4 resulted in uniform expression of GFP::H2Bzif-1ΔII in all cells as early as in the 4-cell stage (100% embryos 4-cell and older, n>100 for each RNAi; Figure 2B). These results together support the model that MEX-3 and SPN-4 repress expression of ZIF-1, also by direct binding to the zif-1 3′ UTR.

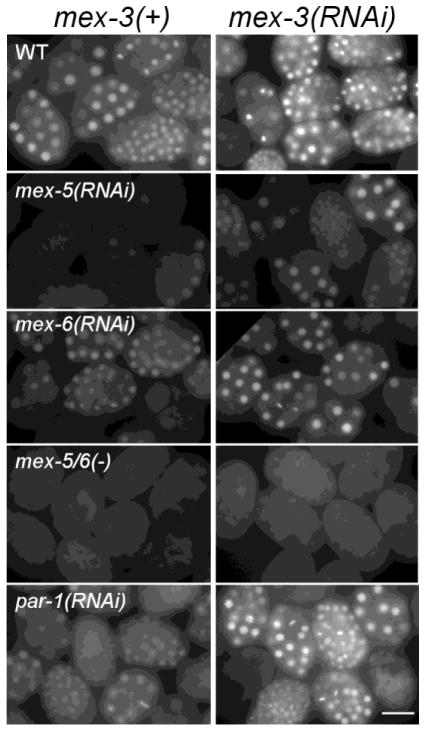

The preferred RNA sequence in vitro for the MEX-3 RNA-binding domain has also been determined (Pagano et al., 2009). Analysis of the zif-1 3′ UTR revealed many possible MEX-3 binding sites, all within Regions II and III, that also overlap putative binding sites for POS-1, MEX-5, or both (Figure 2C and Suppl. Figure S1). Consistent with their partially overlapping binding sites, we could show that MEX-3 and MEX-5/6 function antagonistically in regulating zif-1 expression in vivo. Embryos depleted of mex-5 alone exhibit a reduction in GFP::H2Bzif-1 expression (Figure 4). This reduction can be suppressed when mex-3 is simultaneously depleted. With mex-6(RNAi), which resulted in a mild reduction in GFP::H2Bzif-1 expression, a similar suppression was observed. In fact, depletion of mex-3 in wildtype or par-1(RNAi) embryos resulted in a detectable increase in overall levels of GFP::H2Bzif-1. Depletion of mex-3 did not suppress mex-5(zu199);mex-6(pk440) embryos where MEX-3 is already low or absent (Figure 4).

Figure 4. MEX-3 represses zif-1 expression.

Fluorescence micrographs of GFP::H2Bzif-1 expression in groups of embryos depleted of various proteins (indicated in left column). Each row compares GFP::H2Bzif-1 intensities in the indicated genetic backgrounds between mex-3 depletion (right) or non depletion (left). Depletion of mex-3 increases GFP signal except in the mex-5(zu199) ;mex-6(pk440) [mex-5/6(−)] background which expresses little or no MEX-3 protein. Bar: 30 μM.

MEX-3 and SPN-4 function together in repressing ZIF-1 expression

The result that depletion of either mex-3 or spn-4 resulted in a uniform expression of GFP::H2Bzif-1 Δ II in all cells as early as the 4-cell stage (Figure 2B) was somewhat unexpected, as SPN-4 has always been considered germline blastomere-enriched, and MEX-3 somatic blastomere-enriched (Draper et al., 1996; Ogura et al., 2003). Both SPN-4 and MEX-3 proteins are present at high levels in 1-cell embryos. At each germline blastomere division, SPN-4 protein is initially equal between the two daughters, but is then degraded only in the somatic daughters (Supplemental Figures S2 and S3) (Ogura et al., 2003). MEX-3, on the other hand, is enriched in AB after the first mitotic division. Low levels of MEX-3 remain in germline blastomeres where it, like many RNA-binding proteins identified in germline blastomeres, associates with germline specific P-granules. The uniform expression of GFP::H2Bzif-1ΔII in spn-4(RNAi) and mex-3(RNAi) embryos, combined with asymmetric localization of both SPN-4 and MEX-3 after the 2-cell stage, suggests a repressive function for both SPN-4 and MEX-3 in 1- or 2-cell stage embryos.

Consistent with the above possibility, depletion of spn-4 in wildtype embryos by RNAi resulted in the detection of GFP::H2Bzif-1 in P2 and EMS of very young 4-cell embryos (100%, n=120, Figure 5A). GFP::H2Bzif-1 can also be detected in both P2 and EMS of early 4-cell embryos derived from mex-3(zu155) mutant worms (100%, n=40). For mex-3(zu155) worms that are also depleted of spn-4 by RNAi, GFP::H2Bzif-1 signal can be detected, albeit weakly, as early as 2-cell embryos (10%, n=50). Further supporting the early repressive function of SPN-4, we showed that a GFP::H2B reporter regulated by only Regions II and III of the zif-1 3′ UTR (GFP::H2Bzif-1 II+III), a region not bound by SPN-4 in our in vitro binding assay (Figure 1D and 1E), is properly repressed in oocytes, where repression is OMA-1/2-dependent (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2010), but uniformly expressed in embryos as early as the 2-cell stage (Figure 1C).

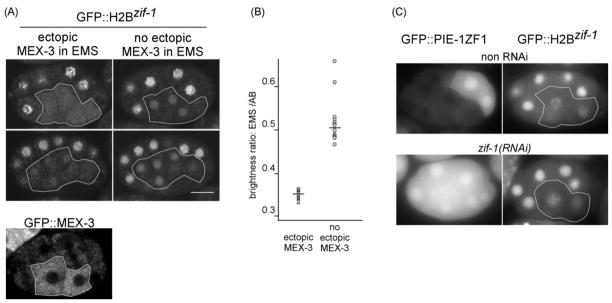

Figure 5. MEX-3 and SPN-4 function together to repress zif-1 expression.

A) Fluorescence micrographs of GFP::H2Bzif-1 expression in 2-cell and 4-cell wildtype, mex-3(zu155), spn-4(RNAi), or mex-3(zu155);spn-4(RNAi) embryos. GFP::H2Bzif-1 signal can be detected in all blastomeres in early 4-cell embryos upon depletion of mex-3, spn-4, or both. GFP was detected in some 2-cell embryos depleted of both genes. (B) Fluorescence micrographs of 4-cell embryos expressing GFP::H2Bzif-1 or GFP::PIE-1 ZF1 in the indicated genetic backgrounds. GFP::H2Bzif-1 expression in somatic blastomeres (arrows) is ectopically repressed in oma-1 (zu405) embryos. The GFP::H2Bzif-1 defect in oma-1(zu405) is suppressed when mex-3 or spn-4 is depleted. A reciprocal pattern is seen in embryos carrying GFP::PIE-1 ZF1. Bar:10 μM.

MEX-3 and SPN-4 have been shown to bind each other in a yeast 2-hybrid assay (Huang et al., 2002). Two lines of evidence support a model that these two proteins function together in regulating zif-1 expression. First, neither SPN-4 nor MEX-3 appears to be sufficient on its own for the translational repression of zif-1, as shown by the following three examples. (1) Depletion of pos-1 results in derepression of zif-1 in germline blastomeres, despite a high level of SPN-4 (and low MEX-3) (Figure 2A). (2) SPN-4, like POS-1, is uniformly distributed in mex-5(zu199);mex-6(pk440) embryos (100%, n=40; Supplemental Figure S2), a genetic background where MEX-3 protein is absent (Schubert et al., 2000). However, POS-1, but not SPN-4, is responsible for the zif-1 repression in mex-5(zu199);mex-6(pk440) embryos. Depletion of pos-1, but not spn-4, restored GFP::H2Bzif-1 expression in mex-5(zu199);mex-6(pk440) embryos (Figure 3). (3) Similarly, we observed no ectopic repression of GFP::H2Bzif-1 in spn-4(RNAi) embryos (data not shown), which have been shown to maintain high MEX-3 levels in all blastomeres until approximately the 28-cell stage (Huang et al., 2002). The second line of evidence supporting SPN-4 and MEX-3 acting together comes from analysis in the oma-1(zu405) genetic background. We showed previously that the oma-1(zu405) missense mutation results in OMA-1 protein persisting past the 1-cell stage and repressing translation of zif-1 in somatic blastomeres (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2010; Nishi and Lin, 2005). The ectopic zif-1 repression in oma-1(zu405) embryos is most apparent in 4-cell embryos, and progressively lessens in older embryos (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2010). Degradation of many maternally-supplied proteins is also defective in oma-1(zu405) embryos, including MEX-5/6, POS-1, MEX-3, and SPN-4 (Lin, 2003) and Supplemental Figure S3). We find that depletion of mex-3 or spn-4, but not pos-1 or mex-5/6, partially suppresses the ectopic repression of zif-1 (40%, n=20 for mex-3(RNAi) and 70%, n=20 for spn-4(RNAi)) and degradation of GFP::PIE-1 ZF1 in oma-1(zu405) embryos (50%, n=50 for mex-3(RNAi) and 85%, n=50 for spn-4(RNAi); Figure 5B and supplemental Figure S4).

Expression of zif-1 in newly formed somatic cells requires high MEX-5/6 and low MEX-3 levels

One interesting question that remains is how zif-1 expression is turned on in somatic daughters (EMS, C, and D) newly divided from a germline blastomere where zif-1 is actively repressed. Although POS-1 and SPN-4 are germline-enriched proteins, their levels are initially equal and high between newly formed somatic cells and their sister germline blastomeres (Ogura et al., 2003; Tabara et al., 1999). Therefore, initiation of zif-1 expression can not be explained by the asymmetric localization of its repressors, POS-1 and SPN-4. The levels of MEX-5/6, the positive regulators of zif-1 expression, are coincidently increased in all newly formed somatic blastomeres (Schubert et al., 2000). Because MEX-5/6 antagonizes repression by POS-1, it is possible that an increase in MEX-5/6 levels is sufficient to allow zif-1 expression in these newly-formed somatic blastomeres. In addition, we considered whether two other factors contribute to the initiation of zif-1 expression in newly formed somatic cells. First, levels of MEX-3 protein, which negatively regulates zif-1 expression and is a likely cofactor for SPN-4, are low in newly formed somatic blastomeres (Draper et al., 1996), and this might be important to relieve repression. Second, degradation of POS-1, which is both a substrate of ZIF-1 as well as a repressor of zif-1 expression, could initiate a positive feedback loop that facilitates zif-1 expression to high levels. SPN-4 is subsequently be degraded by a yet unknown mechanism.

If a low level of MEX-3 protein is critical for the onset of translation of zif-1, then in embryos in which MEX-3 is ectopically expressed in the EMS lineage, GFP::H2Bzif-1 expression should be decreased or abolished. The med-1 promoter has been shown to drive GFP-fused transgenic proteins specifically in the EMS lineage (Maduro et al., 2001). We were unable to use two different fluorescent tags for this experiment for technical reasons: H2Bzif-1 tagged with mCherry exhibited slower maturation and degradation than GFP and we were unable to recover mCherry::MEX-3 expressing lines for unknown reasons. However, because MEX-3 is expressed exclusively in the cytoplasm (Figure 6A) and GFP::H2Bzif-1 is primarily nuclear, we were able to assay the effect on GFP::H2Bzif-1 expression by confocal microscopy of embryos also expressing cytoplasmic GFP::MEX-3. In addition, cytoplasmic GFP::MEX-3 is degraded very rapidly and is mostly undetectable in 28-cell stage embryos, the stage at which we analyzed the effect on nuclear GFP::H2Bzif-1 expression (Figure 6A). At the 28-cell stage, there are six blastomeres derived from the EMS blastomere, four from MS and two from E blastomeres. We measured nuclear GFP signal in the EMS descendants and AB descendants on the same focal planes. Nuclear GFP signal in the four MS descendants and two E descendants is presented as a ratio to the nuclear GFP signal in the AB blastomeres of the same embryo. Nuclear GFP in EMS descendants is significantly lower in embryos expressing ectopic GFP::MEX-3 than embryos without ectopic GFP::MEX-3 (Figure 6A, 6B). This supports the model that a low level of MEX-3 protein in newly formed somatic blastomeres is important to relieve zif-1 translational repression.

Figure 6. Low MEX-3 levels are important for zif-1 expression in newly-formed somatic cells.

(A) Top two rows: confocal microscopy images of embryos expressing GFP::H2Bzif-1 with (left column) or without (right column) ectopic GFP::MEX-3 in the EMS lineage descendents (outlined). Top row: 16-cell stage. Second row: the same embryos at 28-cell stage. The bottom panel shows the exclusive cytoplasmic signal from GFP::MEX-3 in a 12-cell embryo without GFP::H2Bzif-1. (B) Quantification of GFP::H2Bzif-1 signal in embryos with or without GFP::MEX-3 in the EMS lineage of 28-cell embryos. Y axis represents the ratio of average nuclear GFP intensity in the EMS lineage to that in the AB lineage in individual embryos. Thirteen embryos of each genotype were scored. — = mean. (C) Fluorescence micrographs of embryos expressing GFP::PIE-1 ZF1 (left column) or GFP::H2Bzif-1 (right column) in wildtype and zif-1(RNAi) backgrounds. The onset of GFP::H2Bzif-1 expression remains unchanged upon zif-1(RNAi). Bar:10 μM.

To test whether degradation of POS-1 in EMS is required for translation of zif-1 in EMS, we depleted zif-1 by RNAi and assayed the onset of GFP::H2Bzif-1 signal in EMS compared to that in non RNAi embryos. We also depleted zif-1 in the strain expressing GFP::PIE-1ZF1 in a parallel experiment as a control to monitor the effect of zif-1(RNAi) on the degradation of ZIF-1 targets. zif-1(RNAi) resulted in a defect in the degradation of, and therefore uniform distribution of, GFP::PIE-1 ZF1 in embryos up to at least the 20-cell stage (100%, n>100). Despite successful inhibition of GFP::PIE-1 ZF1 degradation, we observed no difference in the timing of onset of expression for GFP::H2Bzif-1 in the EMS lineage (0%, n=30; Figure 6C). This result suggests that degradation of POS-1 is not important for translation of zif-1 in EMS.

Discussion

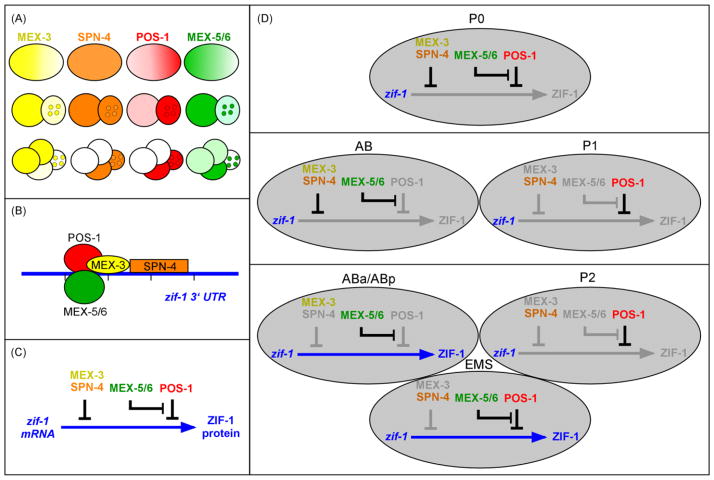

Spatial and temporal restriction of ZIF-1 expression exclusively to somatic blastomeres is critical to achieve localization of PIE-1 specifically to germline blastomeres. We show here that the combination of both repression in germline blastomeres and activation in somatic blastomeres results in somatic cell-specific expression of zif-1. Multiple RNA-binding proteins, which individually can either activate or repress zif-1 expression via direct binding to the zif-1 3′ UTR, function in a combinatorial fashion to effect either net repression or net activation of zif-1 translation. Many of these RNA-binding proteins physically interact with one another as well as compete for the same or overlapping binding sites (Figure 7). As zif-1 RNA is maternally supplied and uniformly distributed in early embryos (http://nematode.lab.nig.ac.jp/db2/ShowCloneInfo.php?clone=570e9), we believe that the effect on ZIF-1 expression by these RNA-binding proteins is primarily through translational regulation.

Figure 7. Model.

Schematic representation showing (A) endogenous expression patterns of MEX-3 (yellow), SPN-4 (orange), POS-1 (red), and MEX-5/6 (green) in 1-, 2- and 4-cell embryos, (B) the deduced binding sites on the zif-1 3′ UTR for MEX-3, SPN-4, POS-1, and MEX-5/6 based on our RNA-binding assays, and (C) the proposed effects of these RNA-binding factors on zif-1 translation. (D) Proposed regulation of zif-1 translation in each early blastomere, as a result of the combinatorial effects of MEX-3, SPN-4, POS-1, and MEX-5/6, resulting from the dynamic temporal and spatial localization of each protein. Gray arrow: no ZIF-1 expression; blue arrow: ZIF-1 expression. See text for details.

We show that POS-1, SPN-4, and MEX-3 all repress expression of the zif-1 reporter (Figure 7). MEX-3 and SPN-4 have been shown to physically interact (Huang et al., 2002). Our results that both MEX-3 and SPN-4 are required for complete repression of ZIF-1 expression support a model that they function together to effect zif-1 repression. However, we can not rule out the possibility that MEX-3 and SPN-4 function in parallel pathways. It is possible that physical binding between these two proteins stabilizes their binding to target RNA(s). Further biochemical analyses will be needed to address this possibility. We propose that wherever MEX-3 and SPN-4 co-localize, such as P0, they repress translation of zif-1. After the first division, both MEX-3 and SPN-4 are initially present at high levels in both daughters (Draper et al., 1996; Ogura et al., 2003). Therefore, zif-1 continues to be repressed in both blastomeres. Translational repression of zif-1 in AB is lifted following degradation of SPN-4 later in the cell cycle through an unidentified mechanism, which results in ready detection of zif-1 translational reporters in ABa and ABp. Meanwhile, MEX-3 decreases in level in P1, and becomes primarily localized to the germline P-granules. We do not believe that the MEX-3 in P-granules functions in conjunction with SPN-4 to repress ZIF-1 expression, as depletion of POS-1 resulted in the derepression of the zif-1 transgene in later germline blastomeres where SPN-4 and P-granule-bound MEX-3 are present (Draper et al., 1996; Ogura et al., 2003). It is often observed that the detection of reporter GFP is delayed by one cell cycle compared to the onset of expression of the endogenous protein. Therefore we suggest that continued repression of zif-1 in the P lineage is maintained by the function of POS-1, most likely beginning with the P2 blastomere. Our finding that POS-1 and MEX-3 repress translation of zif-1 is consistent with previous findings that reduced levels of PIE-1, and therefore derepression of zygotic transcription, were detected in P4 blastomeres of both pos-1(−) and mex-3(−) mutant embryos (Tabara et al., 1999; Tenenhaus et al., 1998).

In EMS, the somatic daughter of the germline blastomere P1, levels of the translational repressors POS-1 and SPN-4 are initially high but zif-1 is nonetheless translated. We find that translation of zif-1 results from the combination of low levels of MEX-3, without which SPN-4 does not repress, along with a high level of activators MEX-5 and MEX-6, which antagonize repression by POS-1 (see below). Ectopic expression of MEX-3 in EMS, where SPN-4 levels are high, is sufficient to prevent or delay zif-1 translation.

Translation of zif-1 in somatic blastomeres requires MEX-5 and MEX-6. We show that MEX-5/6 have dual roles in promoting translation of zif-1 in somatic blastomeres. First, they restrict POS-1, along with several other proteins, to germline blastomeres through their function in maintaining embryonic polarity (Schubert et al., 2000). Second, they bind to the zif-1 3′ UTR, enabling its translation. However, binding of MEX-5/6 to the zif-1 3′ UTR is not absolutely required for ZIF-1 translation, as evidenced by ZIF-1 expression in pos-1;mex-5;mex-6 embryos. Instead, MEX-5/6 binding to the zif-1 3′ UTR enables ZIF-1 expression by preventing binding of repressors to the same region. This model is supported by the extensive overlap of MEX-5/6 and POS-1 binding sites in Region II, and that MEX-5 binding impedes POS-1 binding to the zif-1 3′ UTR in our in vitro assay. The antagonistic functions between MEX-5/6 and POS-1 are consistent with previous genetic analyses showing that a reduced dosage of pos-1 suppresses the mex-5 mutant phenotype (Tenlen et al., 2006). Our results here present a molecular mechanism for the requirement for MEX-5/6 in ZIF-1-mediated target protein degradation (DeRenzo et al., 2003). Furthermore, these results explain how MEX-5/6 can be expressed at a high level in cells where ZIF-1 degrading activity is also high, and how MEX-5/6 promote ZIF-1 degrading activity while simultaneously being substrates of ZIF-1 themselves (DeRenzo et al., 2003).

The region of the zif-1 3′UTR bound by MEX-5/6 also partially overlaps with the binding sites for MEX-3 and OMA-1/2, three other key repressors of zif-1 translation (Figure 7B) (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2010; Pagano et al., 2009). We find that MEX-5/6 also antagonize repression of zif-1 by MEX-3 and OMA-1/2 (M. O. and R. L., unpublished data). We did not, however, observe a clear competitive advantage for MEX-5 binding over MEX-3 binding in our in vitro pull down assay (M. O. and R. L., unpublished data). It is possible that the mechanism by which MEX-5/6 antagonize repression by MEX-3 is different from that utilized against POS-1. MEX-5/6 bind to MEX-3 in a yeast 2-hybrid assay (Huang et al., 2002). Therefore, MEX-5/6 could antagonize translational repression by MEX-3 through a protein-protein interaction, preventing MEX-3 from binding to the zif-1 3′ UTR. In cells where activators MEX-5/6 and their competing repressors, POS-1, MEX-3, or OMA-1/2 co-localize, the outcome regarding zif-1 translation will likely be determined by the relative abundance of MEX-5/6 and their competing repressors.

POS-1 is both a repressor of zif-1 translation as well as a target of ZIF-1-mediated degradation. This suggests a positive feedback loop, whereby degradation of some POS-1 would lead to further relief from POS-1-mediated repression, could be effective in accelerating the relief from translational repression of zif-1 by POS-1 in newly formed somatic sisters of P lineage blastomeres. However, we detected no difference in the expression of GFP::H2Bzif-1 when zif-1 was depleted by RNAi, suggesting that such a positive feedback loop does not play a major role in the onset of zif-1 translation in EMS. It is likely that the level of MEX-5/6 in EMS is already sufficiently higher than that of POS-1 such that any further reduction of POS-1 levels would be inconsequential for the onset of zif-1 translation. MEX-5/6 are themselves also targets of ZIF-1 degradation (DeRenzo et al., 2003), suggesting a possible negative feedback loop for zif-1 translation which would limit the duration of ZIF-1 translation in somatic blastomeres. The effect of zif-1 RNAi on the onset of GFP::H2Bzif-1 expression might therefore be compounded by the simultaneous inhibition of both positive and negative feedback loops.

Transcriptional repression is critical for maintaining both the stability and the totipotency of the germline. Proper development of the germline is, therefore, one of the most critical processes to occur during C. elegans early embryogenesis. However, the mechanism that has evolved to segregate PIE-1 to the germline precursors is not 100% effective, and some PIE-1 remains in the somatic sisters following division (Reese et al., 2000). Cell cycles last only 10–15 minutes in early C. elegans embryos (Seydoux and Fire, 1994), therefore any residual PIE-1 in somatic cells would interfere with the rapid onset of zygotic transcription that is crucial for somatic development. Asymmetric translation of ZIF-1 in somatic blastomere ensures rapid degradation of PIE-1 in somatic blastomeres.

To have so many RNA-binding factors, acting both positively and negatively, regulating the translation of zif-1 simply to establish a somatic cell-specific translation pattern might seem to be overly complicated. Particularly counterintuitive is the discovery that zif-1 expression is repressed by MEX-3, a protein enriched in somatic cells where zif-1 is ultimately expressed. We suggest that C. elegans embryos are faced with a particularly unique challenge due to two aspects of their developmental program: (1) the way in which their germ cell precursors are specified (Strome and Lehmann, 2007), and (2) the fact that many maternally-supplied proteins, including almost all key RNA-binding proteins, are already translated prior to fertilization. It makes good sense for worms to utilize the germline blastomere-specific protein, POS-1, to repress the translation of zif-1 in germline blastomeres, and blastomere specific proteins, MEX-5 and MEX-6, to compete with POS-1 and promote translation in newly formed somatic blastomeres. However, POS-1 and MEX-5/6 are all maternally-supplied proteins and are all present at a high level in the 1-cell embryo, P0, before being asymmetrically segregated to germline and somatic blastomeres, respectively. P0, like the other P lineage blastomeres, is a precursor for both somatic and germline blastomeres. High levels of POS-1, MEX-5, and MEX-6 in P0 would be predicted to promote the translation of zif-1, leading to precocious degradation of PIE-1 and embryonic lethality. C. elegans circumvents this dilemma by utilizing two additional RNA-binding proteins, SPN-4 and MEX-3, whose expression patterns only overlap in the 1-cell and 2-cell embryos, to function together to repress zif-1 translation in 1- and 2- cell embryos. After the 2-cell stage, repression by SPN-4 and MEX-3 is relieved, and germline versus somatic regulation of ZIF-1 expression initiates. Repression in germline blastomeres is continued by the germline protein POS-1, and embryos only need to control zif-1 translation in newly-formed somatic blastomeres.

We propose that multiple RNA-binding proteins, expressed in individual dynamic temporal and spatial patterns, function in a combinatorial manner to prevent the precocious translation of zif-1, localizing ZIF-1 activity strictly to the somatic blastomeres. Such regulation is essential for the stability of PIE-1 in germline blastomeres, global transcriptional repression in the germline precursors, and ultimately the maintenance of germline integrity and totipotency.

Experimental Procedures

Strains

N2 was used as the wildtype strain. Genetic markers are: LGII, mex-6 (pk440) ; LGIII, unc-119(ed3); LGIV, oma-1(zu405), oma-1(zu405, te33), mex-5 (zu199) ; LGV, oma- 2(te51). Plasmids used, strain names and transgenes are as follows: TX1246 (teIs113 [Ppie-1gfp::h2b::UTRzif-1,771bp]), TX1251 (teIs604 [Ppie-1gfp::h2b::UTRzif-1,771bp,Δ4–63]), TX1288 (oma-1(zu405 ; te33)/nT1 ; oma-2(te51)/nT1 ; teIs114 [Ppie-1gfp ::h2b :: UTRzif- 1,771bp]), TX1298 (teEx607 [Ppie-1gfp::h2b::UTRzif-1,771bp, Δ184–243]), TX1311 (teEx610 [Ppie- 1gfp::h2b::UTRzif-1,771bp, 64–183]), TX1481 (mex-6(pk440) ; unc-30(e191)mex- 5(zu199)/nT1 ; teIs113 [Ppie-1gfp ::h2b :: UTRzif-1,771bp]), TX1513 (mex-6(pk440) ; unc- 30(e191)mex-5(zu199)/nT1 ; axEx1120 [Ppie-1gfp ::pie-1 zf1::UTRpie-1, pRF4]), TX1533 (teIs140 [Ppie-1gfp::h2b::UTRzif-1,771bp, Δ64–123]), TX1541 (teIs143 [Ppie-1gfp::h2b::UTRzif- 1,771bp, Δ114–183]), TX1543 (teIs145 [Ppie-1gfp::h2b::UTRzif-1,771bp, Δ64–183]), TX1567 (teEx719 [Pmed-1gfp ::mex-3]), TX1570 (teIs113 [Ppie-1gfp ::h2b::UTRzif-1,771bp] ;teEx719 [Pmed- 1gfp ::mex-3]), JH1436 (axEx1120 [Ppie-1gfp ::pie-1 zf1::UTRpie-1, pRF4]).

Plasmid construction

Most plasmids were constructed with the Gateway cloning technology as previously described (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2010). The in vivo 3′ UTR functional assays used the 771 nt genomic sequence downstream of the zif-1 stop codon, which was cloned downstream of pie-1 promoter-driven GFP::H2B in the germline expression vector pID3.01B (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2010; Reese et al., 2000). All deletion constructs were derived from the 771 nucleotide sequence (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2010). The mex-3 cDNA was cloned downstream of the med-1 promoter-driven GFP (Maduro et al., 2001).

C. elegans transformation

All integrated lines were generated by microparticle bombardment (Praitis et al., 2001) whereas other transgenic lines were generated by complex array injection (Kelly et al., 1997). The GFP::MEX-3 expressing line was generated by micro-injection. For each construct, expression was analyzed and found to be consistent in at least two independent lines.

RNA interference

Feeding RNAi was performed as described (Timmons and Fire, 1998) using HT115 bacteria seeded on NGM plates containing 1mM IPTG. L1 larvae were fed for 2 days at 25°C.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence for C. elegans embryos was carried out as described previously: for anti-SPN-4 (1/10,000, rabbit) (Ogura et al., 2003). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa568 conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Invitrogen, 1/250).

RNA binding assay

MBP-tagged proteins were prepared by cloning individual cDNAs into pDEST-MAL (Invitrogen). These expression clones were transformed into Rosetta cells, induced with 1mM IPTG for 4 hours at room temperature in the presence of 0.2% glucose and 0.1 mM zinc, purified by amylose resin (NEB) as previously described (Nishi and Lin, 2005), and eluted with 50 mM maltose.

Biotinylation of RNA and pull-downs were performed as previously described (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2010; Lee and Schedl, 2001) except for the following modifications. The optimal amount of purified protein and the zif-1 3′ UTR were empirically determined by titration series. Each binding reaction contained 150 ng of the purified MBP-tagged protein and 100 ng/60 nucleotides of biotinylated RNA. For the competition binding assay shown in Figure 2D, 1μg of each MBP-tagged protein and 30ng/60 nt RNA were used.

Analysis of embryos, imaging, and quantification

All images except those shown in Figure 6A were obtained with an Axioplan microscope (Zeiss) equipped with a MicroMax-512EBFT CCD camera (Princeton Instruments) controlled by the Metamorph acquisition software (Molecular Devices) (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2008). Imaging for Figure 6A was performed with a LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope (Zeiss) and quantified with ImageJ software (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2008). Nuclear GFP intensity was quantified for cells in 28-cell embryos. Embryos were imaged at multiple time points to evaluate the expression of GFP::MEX-3 at 12–16-cell stages and the levels of GFP at 20–50-cell stages. The ratios of nuclear GFP intensities in EMS descendants to that in AB descendants for individual embryos were plotted in Figure 6B.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Molecular regulation in somatic cells newly segregated from a germline blastomere

Mechanistic insights in translational regulation not predicted by the known genetics

Provides an encompassing view of ZIF-1 translational regulation during embryogenesis

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lin lab members for discussions, Lesilee Rose for spn-2 cDNA, Kuppuswamy Subramaniam and Geraldine Seydoux for the germline expression vector, Geraldine Seydoux for JH1436, Yuji Kohara for the anti-SPN-4 antibody, Wormbase for valuable information, and C. elegans Genetics Center (CGC) for various strains. This work was supported by NIH grants (HD37933 and GM84198) to R. L.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Batchelder C, Dunn MA, Choy B, Suh Y, Cassie C, Shim EY, Shin TH, Mello C, Seydoux G, Blackwell TK. Transcriptional repression by the Caenorhabditis elegans germ-line protein PIE-1. Genes Dev. 1999;13:202–12. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.2.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng KC, Klancer R, Singson A, Seydoux G. Regulation of MBK-2/DYRK by CDK-1 and the pseudophosphatases EGG-4 and EGG-5 during the oocyte-to-embryo transition. Cell. 2009;139:560–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRenzo C, Reese KJ, Seydoux G. Exclusion of germ plasm proteins from somatic lineages by cullin-dependent degradation. Nature. 2003;424:685–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01887.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detwiler MR, Reuben M, Li X, Rogers E, Lin R. Two zinc finger proteins, OMA-1 and OMA-2, are redundantly required for oocyte maturation in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2001;1:187–99. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper BW, Mello CC, Bowerman B, Hardin J, Priess JR. MEX-3 is a KH domain protein that regulates blastomere identity in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1996;87:205–16. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley BM, Pagano JM, Ryder SP. RNA target specificity of the embryonic cell fate determinant POS-1. RNA. 2008;14:2685–97. doi: 10.1261/rna.1256708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D, Seydoux G. Inhibition of transcription by the Caenorhabditis elegans germline protein PIE-1: genetic evidence for distinct mechanisms targeting initiation and elongation. Genetics. 2008;178:235–43. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.083212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guedes S, Priess JR. The C. elegans MEX-1 protein is present in germline blastomeres and is a P granule component. Development. 1997;124:731–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guven-Ozkan T, Nishi Y, Robertson SM, Lin R. Global Transcriptional Repression in C. elegans Germline Precursors by Regulated Sequestration of TAF-4. Cell. 2008;135:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guven-Ozkan T, Robertson SM, Nishi Y, Lin R. zif-1 translational repression defines a second, mutually exclusive OMA function in germline transcriptional repression. Development. 2010;137:3373–82. doi: 10.1242/dev.055327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang NN, Mootz DE, Walhout AJ, Vidal M, Hunter CP. MEX-3 interacting proteins link cell polarity to asymmetric gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 2002;129:747–59. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.3.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly WG, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Fire A. Distinct requirements for somatic and germline expression of a generally expressed Caernorhabditis elegans gene. Genetics. 1997;146:227–38. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Schedl T. Identification of in vivo mRNA targets of GLD-1, a maxi-KH motif containing protein required for C. elegans germ cell development. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2408–20. doi: 10.1101/gad.915901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R. A gain-of-function mutation in oma-1, a C. elegans gene required for oocyte maturation, results in delayed degradation of maternal proteins and embryonic lethality. Dev Biol. 2003;258:226–39. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maduro MF, Meneghini MD, Bowerman B, Broitman-Maduro G, Rothman JH. Restriction of mesendoderm to a single blastomere by the combined action of SKN-1 and a GSK-3beta homolog is mediated by MED-1 and -2 in C. elegans. Mol Cell. 2001;7:475–85. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC, Draper BW, Krause M, Weintraub H, Priess JR. The pie-1 and mex-1 genes and maternal control of blastomere identity in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1992;70:163–76. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90542-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC, Schubert C, Draper B, Zhang W, Lobel R, Priess JR. The PIE-1 protein and germline specification in C. elegans embryos [letter] Nature. 1996;382:710–2. doi: 10.1038/382710a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt C, Rasoloson D, Ko D, Seydoux G. 3′ UTRs are the primary regulators of gene expression in the C. elegans germline. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1476–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, Seydoux G. Less is more: specification of the germline by transcriptional repression. Development. 2008;135:3817–27. doi: 10.1242/dev.022434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi Y, Lin R. DYRK2 and GSK-3 phosphorylate and promote the timely degradation of OMA-1, a key regulator of the oocyte-to-embryo transition in C. elegans. Dev Biol. 2005;288:139–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura K, Kishimoto N, Mitani S, Gengyo-Ando K, Kohara Y. Translational control of maternal glp-1 mRNA by POS-1 and its interacting protein SPN-4 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 2003;130:2495–503. doi: 10.1242/dev.00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano JM, Farley BM, Essien KI, Ryder SP. RNA recognition by the embryonic cell fate determinant and germline totipotency factor MEX-3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20252–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907916106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano JM, Farley BM, McCoig LM, Ryder SP. Molecular basis of RNA recognition by the embryonic polarity determinant MEX-5. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8883–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700079200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praitis V, Casey E, Collar D, Austin J. Creation of low-copy integrated transgenic lines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2001;157:1217–26. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese KJ, Dunn MA, Waddle JA, Seydoux G. Asymmetric segregation of PIE-1 in C. elegans is mediated by two complementary mechanisms that act through separate PIE-1 protein domains. Mol Cell. 2000;6:445–55. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaner CE, Deshpande G, Schedl PD, Kelly WG. A conserved chromatin architecture marks and maintains the restricted germ cell lineage in worms and flies. Dev Cell. 2003;5:747–57. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert CM, Lin R, de Vries CJ, Plasterk RH, Priess JR. MEX-5 and MEX-6 function to establish soma/germline asymmetry in early C. elegans embryos. Mol Cell. 2000;5:671–82. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydoux G, Dunn MA. Transcriptionally repressed germ cells lack a subpopulation of phosphorylated RNA polymerase II in early embryos of Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 1997;124:2191–201. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.11.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydoux G, Fire A. Soma-germline asymmetry in the distributions of embryonic RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1994;120:2823–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama M, Soto MC, Ishidate T, Kim S, Nakamura K, Bei Y, van den Heuvel S, Mello CC. The Conserved Kinases CDK-1, GSK-3, KIN-19, and MBK-2 Promote OMA-1 Destruction to Regulate the Oocyte-to-Embryo Transition in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2006;16:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzel ML, Pellettieri J, Seydoux G. The C. elegans DYRK Kinase MBK-2 Marks Oocyte Proteins for Degradation in Response to Meiotic Maturation. Curr Biol. 2006;16:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome S TCeR Community. Specification of the germ line. WormBook; WormBook: 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome S, Lehmann R. Germ versus soma decisions: lessons from flies and worms. Science. 2007;316:392–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1140846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabara H, Hill RJ, Mello CC, Priess JR, Kohara Y. pos-1 encodes a cytoplasmic zinc-finger protein essential for germline specification in C. elegans. Development. 1999;126:1–11. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus C, Schubert C, Seydoux G. Genetic requirements for PIE-1 localization and inhibition of gene expression in the embryonic germ lineage of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1998;200:212–24. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenlen JR, Schisa JA, Diede SJ, Page BD. Reduced dosage of pos-1 suppresses Mex mutants and reveals complex interactions among CCCH zinc-finger proteins during Caenorhabditis elegans embryogenesis. Genetics. 2006;174:1933–45. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.052621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L, Fire A. Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature. 1998;395:854. doi: 10.1038/27579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Barboric M, Blackwell TK, Peterlin BM. A model of repression: CTD analogs and PIE-1 inhibit transcriptional elongation by P-TEFb. Genes Dev. 2003;17:748–58. doi: 10.1101/gad.1068203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.