Abstract

The aim of this study was to analyze the psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the Motivational Climate Sport Youth Scale (MCSYSp) and invariance across gender and different sports (swimming, soccer, handball, basketball, futsal). A total of 4,569 athletes (3,053 males, 1,516 females) from soccer (1,098), swimming (1,049), basketball (1,754), futsal (340), and handball (328) participated in this study, with ages between 10 and 20 years (M = 15.13; SD = 1.95). The results show that the original model (two factors/12 items) did not adjust to the data in a satisfactory way; therefore, it was necessary to change the model by removing four items (two from each factor). Subsequently, the model adjusted to the data in a satisfactory way (χ2 = 499.84; df = 19; χ2/df = 26.30; p < .001; SRMR = .037; TLI = .923; CFI = .948; RMSEA = .074; IC90% .069–.080) and was invariant by gender and team sports (soccer, handball, basketball, futsal) (ΔCFK≤.01); however, it was not invariant between swimming and team sports (soccer, handball, basketball, futsal) (ΔCFI ≥ .01). In conclusion, the MCSYSp (two factors/eight items) is a valid and reliable choice that is transversal not only to gender, but also to the different studied team sports to measure the perception of the motivational climate in athletes. Future studies can research more deeply the invariance analysis between individual sports to better understand the invariance of the model between individual and team sports.

Key words: motivation, achievement goal theory, sports, gender, multi-group analysis

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a substantial increase in youth sport participation, and sport psychologists have shown considerable interest in understanding the role that the sports experience, as one of the most important organised out-of-school activities, plays in positive personal and life skills development and the promotion of well-being for youth. Positive outcomes are to some extent dependent on the sporting environment created (Rutten et al., 2011). One of the variables likely to be related to the gains young athletes derive from sports participation is the motivational climate created by the coach. The motivational climate focuses on the pattern of normative influences along with evaluative standards and sanctions that are emphasised and communicated in the environment (Gould et al., 2012).

The Achievement Goal Theory (AGT) perspective (Nicholls, 1984) has been one of the most widely used conceptual frameworks for studying motivation in achievement contexts such as school and sport. Drawing from a socialcognitive view of motivation, achievement goal theorists argue that understanding variations in behavioural investment, performance, psychological well-being, and affective responses in achievement contexts requires studying the criteria that individuals employ to judge competence and success. The AGT focuses on both individual achievement goals and the social context or goal structures that form such individual goals (Ames, 1992). Grounded in the AGT, two main climates have been identified that reflect the work of Ames and Nicholls.

A task-involving climate is perceived when team members are directed towards selfimprovement, the coach or parent emphasises learning and personal progress, effort is rewarded, mistakes are seen as part of learning, and choice is allowed. In contrast, an egoinvolving climate is one that encourages interindividual comparison and in which mistakes are punished and high normative ability is rewarded. In a task-involving climate, the coach emphasises and rewards individual improvement and effort, offers task variety that matches different ability levels, and encourages athletes to take leadership roles and make decisions. In an ego-involving climate, the coach evaluates and rewards athletes based on normative/comparative ability, encourages inter-individual comparison, forms homogeneous groups based on ability levels, and discourages athlete’s initiative (Keegan et al., 2011). When coaches create an ego-involving climate, they tend to give differential attention to and focus positive reinforcement on the athletes who are most competent and instrumental to winning, emphasising the importance of winning. Skill development is in the service of outperforming others rather than personal improvement, and mistakes may evoke punitive behaviours from the coach (Duda and Ntoumanis, 2005).

In general, research on the coach-created motivational climate demonstrates that a coach-created task-involving climate, compared to an ego-involving climate, is linked to more adaptive behavioural patterns and more positive cognitive and emotional responses among athletes (Duda and Balaguer, 2007). According to Keegan et al. (2011), there appears to be a strong case that the perception of an environment emphasising/promoting mastery concept is likely to produce numerous adaptive and desirable consequences for the participation and development of sports performers. In contrast, when participants perceive performance climates, there seem to be less frequently positive or adaptive motivational undesirable beliefs and patterns of behaviour.

Following an assertion of Ames (1992) and Nicholls (1984) that the perception of the motivational environment is critical, a number of questionnaires have emerged to assess the perceived situational and contextual goals emphasised in sports setting (Keegan et al., 2011). These questionnaires include the Perceived Motivational Climate Sport Questionnaire-2 (PMCSQ-2: Newton et al., 2000), which is used to assess the motivational climate created by coaches in sport and developed using adolescent and adult populations.

However, according to the Nicholls’s (1984) concept, the youth move through a series of cognitive-developmental stages as they mature, suggesting that the youth possess an immature concept of ability until around the age of 12 years, when the capacity to distinguish ability from effort and luck and the capacity to judge task difficulty in normative terms are acquired. Until these capacities are acquired, it is believed that the youth are not fully capable of adopting a differentiated concept of ability in achievement contexts.

Influenced by the Nicholls’s (1984) perspective and under the Youth Enrichment Through Sport (YES) project, Smith et al. (2008) chose to develop an age-appropriate measure of motivational climate (MCSYS: Motivational Climate Scale for Youth Sports) derived from the PMCSQ-2, and it has a Flesh–Kincaid reading level of Grade 3.3. The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level index is one way to measure and report the readability of English text, meaning that the score of 3.3 indicates that a third-fourth grader would be able to read the items. The MCSYS (Smith et al., 2008) is a 12-item scale that is divided into two subscales (task and ego-involving). To ensure content validity relative to the PMCSQ-2, all 6 of the PMCSQ-2 subscales identified by Newton et al. (2000) are represented among the MCSYS items, some of which were rewritten. The development of the MCSYS used 992 male and female athletes aged 9 to 16 years, and the results revealed a strong goodness of the fit index in the hypothesised two-factor model, as well as good internal consistency.

On the other hand, according to Duda (2001), the evaluation of motivational climate perception in the physical activity and sports field has some limitations. This issue is perhaps related to the diversity of sub-dimensions underlying the main conceptual framework, without excluding the specific psychosocial characteristics of each context, since the up-to-date investigation in the field of evaluation of motivational climate perception shows some slippage in the concept because if affective variables (e.g. worry about one’s performance) are assumed to be components rather than correlates of the perceived motivational climate, we cannot then proceed to examine affective consequences of the situationally emphasized goal perspective as these have been embraced within the construct itself (Duda and Whitehead, 1998). In our opinion, this issue can be proven by analysing the validation results of some measurement instruments developed to evaluate the motivation climate perception in the sports field (PMCSQ-2: Newton et al., 2000; Peer Motivational Climate Youth Sports Questionnaire - PMCYSQ: Ntoumanis and Vazou, 2005), whereas, as they are formed by subscales (1st order factors) underlying the two main scales (2nd order factors: ego and task), they present some adjustment problems. This is not observed in the questionnaires formed by a factorial structure with only two dimensions, as it is in the case of the MCSYS (Smith et al., 2008).

Accordingly with Duda and Whitehead (1998), despite the possibility of motivational climate multidimensionality, researchers should make clear their intentions about: a) exploring all the variables that potentially influence achievement goals and explain the maximum results variation; or b) examining what are the consequences for the individuals of perceiving different kinds of the motivational climate. In the present study, the main purpose was to validate a questionnaire that would clearly measure the motivational climate in sports underlying AGT (Nicholls, 1984). It would allow for future research to establish the direction of causality in these relationships, in order to determine whether the creation of climates high in mastery cues (for example) leads to the perception of a mastery climate and the numerous associated positive motivational consequences (Keegan et al., 2011).

There are also other instruments with a two factor structure, but they were developed for physical education (Perception Learning and Performance Orientations in Physical Education Classes Questionnaire, Papaioannou, 1998 – LAPOPECQ), physical activity and noncompetitive sports (Motivational Climate Perceived in Peers Scale (CMI – acronym in Spanish), Moreno-Murcia et al., 2006) or an exercise domain (Perceived Motivational Climate Exercise Questionnaire, Cid et al., 2012 - PMCEQ). On the other hand, the instruments normally used to measure the motivational climate have been developed using adolescent and adult populations, and the advantage of the MCSYS is that it also refers to younger athletes. This is one of the relevant developmental considerations influencing assessment among youth athletes highlighted by Harris et al. (2013). Besides that, the Portuguese version of the MCSYSp (Borrego and Silva, 2012) has also been demonstrated to be adequate, and results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) revealed a good fit to data in the hypothesised two-factor model. However, in this study only a sample of young basketball players was employed.

As Biddle (2001) suggests, from the assessment point of view, it seems more satisfactory to use instruments with only two factors: task-involving climate and ego-involving climate. Therefore, if the researcher’s objective is to study the impact that motivational climate perception has on other variables, then the best option is to use a valid and reliable measure that simply evaluates the subject’s perception of success that is inherent to all achievement contexts (Roberts, 2001). Duda and Whitehead (1998) suggest that perhaps this area of measurement would be more conceptually tidy if we restrict the assessment of the perceived climate to the elements of task versus ego involving situations identified in the AGT by Nicholls (1984).

These are the main reasons why the MCSYS was chosen to assess the motivational climate in sport domains in the present study. Thus, the major purpose of this research was to determine the extent to which the MCSYSp was valid, reliable and equivalent (i.e. invariant) across athletes of different sports and also between genders.

The establishment of measurement invariance is one of the crucial aspects for the development and use of psychometric instruments (e.g., determines if they are equivalent in different populations, subgroups and contexts) (Cheung and Rensvold, 2002). This technique is increasingly used in psychometric validation studies and multi-group comparison studies (Sass, 2011); in the present study it allowed us to make appropriate comparisons between sports (individual and team) and gender (males and females). Thus, according to the conceptual framework referred, we hypothesised that the dimensions evaluated by the MCSYSp would be equivalent (invariant) both in terms of the different sports and between genders, underlying the AGT’s model.

Methods

Participants

General sample

The sample was comprised of 4,569 federated athletes (3,053 males, 1,516 females) from soccer (1,098), swimming (1,049), basketball (1,754), futsal (i.e. 5-a-side indoor soccer) (340), and handball (328) who were aged between 10 and 20 years (M = 15.13; SD = 1.95); all athletes practiced their sport at the national level. The training experience of the athletes varied from 1 to 15 years (M = 5.86; SD = 3.05). The study was conducted with athletes from these sport disciplines since they were the most representative team and individual sports in Portugal (i.e. with more federate athletes) according to the Portuguese Institute of Sports and Youth (IPDJ, 2015). More details about samples are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Measurement Models | χ2 | df | χ2/df | p | SRMR | NNFI | CFI | RMSEA | RMSEA-90% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Model | 2171.52 | 53 | 40.97 | <.001 | .064 | .815 | .852 | .094 | .090–.097 |

| Final Model | 499.84 | 19 | 26.30 | <.001 | .037 | .923 | .948 | .074 | .069–.080 |

| Male Model | 292.15 | 19 | 15.37 | <.0010 | .035 | .933 | .954 | .062 | .062–.076 |

| Female Model | 237.93 | 19 | 12.52 | <.0010 | .045 | .904 | .935 | .081 | .077–.097 |

| Soccer Model | 80.15 | 19 | 4.21 | <.001 | .022 | .984 | .989 | .054 | .042–.067 |

| Swimming Model | 173.06 | 19 | 9.10 | <.001 | .044 | .948 | .965 | .079 | .076–.100 |

| Handball Model | 76.34 | 19 | 4.01 | <.001 | .054 | .898 | .931 | .080 | .074–.110 |

| Basketball Model | 222.38 | 19 | 11.70 | <.001 | .044 | .915 | .942 | .078 | .069–.088 |

| Futsal Model | 38.06 | 19 | 2.00 | .006 | .041 | .962 | .974 | .054 | .029–.079 |

N = sample size; M = mean; SD = standard deviation

Measures

The MCSYSp (Borrego and Silva, 2012) was used. This questionnaire consists of 12 items with a five-point Likert scale, which varies between 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) and 5 (“Strongly Agree”). The items were grouped posteriorly into two factors (with six items each), which reflected the underlying AGT (Nicholls, 1984).

Procedures

The data were collected through two different procedures. For basketball, handball, futsal and part of the soccer sample, the following procedure was used:

After obtaining authorisation from the clubs and informed consent from the participants (regarding underage athletes, authorisation was obtained from their legal guardians), all data were collected and analysed anonymously, thus granting the anonymity principle. The data from the questionnaires were collected at the final training sessions in about 15 minutes.

Data regarding the swimming sample and part of the soccer sample were collected by the following procedure:

Every athlete and/or legal guardian was contacted individually by telephone, and, in addition to explaining the study purposes, an email address was requested to send the questionnaire. Each e-mail was individually sent with a different link to each individual, assuring they would only receive the e-mail once; moreover, an intention letter with the research purposes properly signed by all its authors, in which confidentiality principle was safeguarded, was sent. The questionnaires were filled through the Survey Monkey platform, with a mean filling time of 10 minutes.

Adaptation of the questionnaire to the swimming sport

The adaptation process of the questionnaire to the swimming context was conducted by the researchers, who adjusted the team sports terms to the swimming context without modifying their semantic content. This modification only occurred in item 10: ‘Players were taken out of games if they made a mistake’ (team sports) to ‘Athletes who make mistakes do not compete’ (swimming).

Statistical Analysis

To undertake the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), a ratio of 15:1 (the number of subjects by the variables to be estimated) was applied to minimize the issue related to nonnormal data distribution (Hair et al., 2014). According to Byrne (2010), normalized Mardia coefficient values higher than 5 indicated a multivariate non-normal distribution: general sample (29.22), soccer sample (16.06), swimming sample (10.13), basketball sample (36.37), handball sample (18.90), and futsal sample (19.93). As such, the data analysis was undertaken according to the guidance and recommendations of several authors (Byrne, 2010; Hair et al., 2014). Besides the estimated method of maximum likelihood (ML), chi-squared (χ2) testing of the respective degrees of freedom (df), and the level of significance (p), the following adjustment quality indexes were also used: Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the respective confidence interval (90% CI). In the current study, we used the following cut-off values suggested by several authors (Byrne, 2010, Hair et al., 2014; Marsh et al., 2004): SRMR ≤ .08, CFI and NNFI ≥ .90, and RMSEA ≤ .08. Additionally, the convergent validity was analysed via the calculation of the average variance extracted (AVE), considering values of AVE ≥ .50. Also the discriminant validity was analysed; the value of the factors, when above the square of the correlation between the same; and the composite reliability (CR) to assess the internal consistency of the factors, adopting CR ≥ .70 as cutting values (Hair et al., 2014). The analysis was undertaken using AMOS 20.0.

The multigroup analysis has the purpose of evaluating if the structure of the measurement model is equivalent (invariant) in different groups with different characteristics (males vs females or different sports). According to Byrne (2010) and Cheung and Rensvold (2002), in order for invariance to exist, it is necessary to verify two criteria: a) the measurement model should be adjusted to each group; b) to perform a multigroup analysis, it is necessary to examine the following invariance types: configural invariance (unconstrained model), metric invariance (weak invariance), scalar invariance (strong invariance), and residual invariance (strict invariance). According to Cheung and Rensvold (2002), the invariance assumptions are verified through the differences of the χ2 test or CFI, and those should be ΔCFI ≤ .01. The analysis was undertaken using AMOS 20.0.

Results

According to Table 2, it is possible to verify that the model from the MCSYSp (Borrego and Silva, 2012) did not adjust to the data in a satisfactory way, since the cut-off values adopted in the methodology were not reached (i.e., CFI e NNFI was lower than .90, and RMSEA was higher than .08). Therefore, we analysed the modification indexes looking for eventual fragilities that led to the elimination of 4 items (two for each factor). After this procedure, the final model (respecified), with two factors and 8 items, revealed a good adjustment to the general sample as well as gender and sports samples (Byrne, 2010; Hair et al., 2014; Marsh et al., 2004)

Table 2.

Fit indexes of the measurement model of the MCSYS: males & females, soccer, swimming, handball, basketball, and futsal.

| Samples | N | Ages | Gender | Training experience | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| male | female | (years) | |||

| Soccer | 109 | 12 -20 | 1098 | - | 1 - 14 |

| 8 | (M = 14.15; SD = 2.51) | (M = 10.89; SD = 3.78) | |||

| Swimming | 104 | 12 - 20 - | 714 | 335 | 6 -14 |

| 9 | (M = 15.08; SD = 2.47) | (M = 9.22; SD = 2.87) | |||

| Basketball | 175 | 11 -20 | 800 | 954 | 1 - 13 |

| 4 | (M = 14.61; SD = 1.54) | (M = 4.42; SD = 2.55) | |||

| Futsal | 340 | 10 -19 (M = 14.74; SD = 2.22) | 340 | - | 1 - 11 (M = 5.67; SD = 2.96) |

| Handball | 328 | 11 -20 (M = 14.84; SD = 1.40) | 191 | 127 | 1 - 13 (M = 5.37; SD = 2.80) |

χ2 = chi-squared; df = degrees of freedom; χ2/df = normalised chi-squared; SRMR = Standardised Root Mean Square Residual; NNFI = Non-normed Fit Index; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA = Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation; CI = Confidence Interval; General Model (two factors, task- and ego-involving climate, and 12 items from the Portuguese version [Borrego and Silva, 2012]; Final Model (two factors and 8 items).

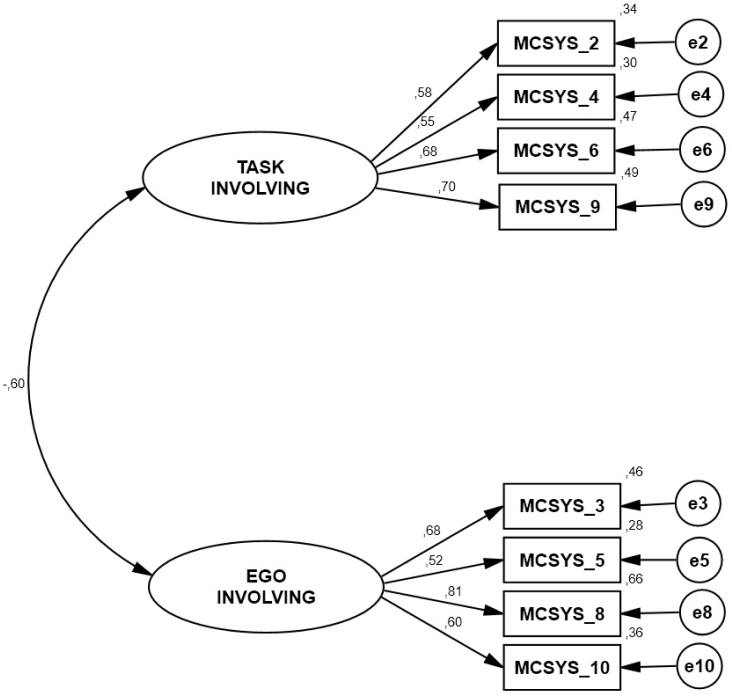

As presented in Figure 1, a significant negative correlation existed between task and ego (r = -.60). Relative to the results of the adjustment of the model’s individual variables, factorial validity was present, i.e. all items had a factorial weight on the respective factor (all statistically significant p < .05) varying from .55 to .70 for the task-involving climate and from .52 to .81 for the ego-involving climate. Regarding internal consistency, in both factors the values of composite reliability (CR) had good internal consistency (task-involving climate [.73] and egoinvolving climate [.75]) and showed a negative and significant correlation (r = -.60) between task- and ego-involving climates.

Figure 1.

Standardised individual variables (covariance factors, factorial weights, and measurement errors), all of which were significant in the measurement model (MCSYSp – two factors/eight items) for all sports

Additionally, considering convergent validity, both factors presented an average variance extracted (AVE) value of .40 (taskinvolving climate) and .45 (ego-involving climate), which was inferior to the value recommended by Hair et al. (2014) (AVE ≥.50). Still, none of the factors presented issues of discriminant validity, as the square of the factor’s correlation (r2 = .36) was inferior to the AVE (Hair et al., 2014).

According to procedures adopted in the methodology (ΔCFI ≤ .01), the measurement model (i.e. two factors, eight items) proved to be invariant across gender (Table 3) and across team sports (Table 4); however, the results did not show evidence of invariance between swimming and team sports (Table 3) because ΔCFI was higher than .01 in all invariance types. In other words, the obtained values indicate that the same number of factors was present in each group and that each of the factors was associated with the same set of items (i.e. configural invariance); the MCSYS presented the same significance in genders and team sports (i.e. metric invariance); comparison of the latent and observed averages was valid across genders and team sports (scalar invariance) as well as residual invariance (what supports the comparison between the observed items). Regarding the comparison swimming and team sports, these assumptions were not verified.

Table 3.

Fit indexes for the invariance of the measurement model of the MCSYS between gender, swimming, and team sports

| Models | x2 | df | Δ x2 | Δdf | P | CFI | ΔCFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male–Female | |||||||

| CI | 530.10 | 38 | - | - | - | .947 | - |

| MI | 548.54 | 44 | 18.44 | 6 | .000 | .946 | .001 |

| SI | 560.35 | 47 | 30.07 | 9 | .000 | .945 | .002 |

| RI | 668.35 | 55 | 138.25 | 17 | .000 | .934 | .013 |

| Swimming–Soccer | |||||||

| CI | 348.74 | 38 | - | - | - | .929 | - |

| MI | 506.48 | 44 | 157.73 | 6 | .000 | .894 | .035 |

| SI | 565.06 | 47 | 216.32 | 9 | .000 | .881 | .048 |

| RI | 839.23 | 55 | 490.48 | 17 | .000 | .820 | .109 |

| Swimming–Basketball | |||||||

| CI | 450.93 | 48 | - | - | - | .929 | - |

| MI | 682.87 | 44 | 231.93 | 6 | .000 | .890 | .039 |

| SI | 717.59 | 47 | 266.65 | 9 | .000 | .885 | .044 |

| RI | 901.69 | 55 | 450.75 | 17 | .000 | .855 | .074 |

| Swimming–Handball | |||||||

| CI | 328.81 | 38 | - | - | - | .912 | - |

| MI | 393.96 | 44 | 65.15 | 6 | .000 | .895 | .017 |

| SI | 402.42 | 47 | 73.61 | 9 | .000 | .893 | .019 |

| RI | 435.67 | 55 | 106.87 | 17 | .000 | .885 | .027 |

| Swimming–Futsal | |||||||

| CI | 290.46 | 38 | - | - | - | .922 | - |

| MI | 409.45 | 44 | 118.99 | 6 | .000 | .887 | .035 |

| SI | 442.50 | 47 | 152.04 | 9 | .000 | .878 | .044 |

| RI | 524.90 | 55 | 234.43 | 17 | .000 | .854 | .068 |

χ2 = chi-squared; df = degrees of freedom; Δχ2 = differences in the value of chi-squared; Δdf = differences in the degrees of freedom; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; ΔCFI = differences in the value of the Comparative Fit Index; CI = configural invariance; MI = measurement invariance; SI = scale invariance; RI = residual invariance

Table 4.

Fit indexes for the invariance of the measurement model of the MCSYS between team sports

| Models | X2 | df | Δ X2 | Δdf | P | CFI | ΔCFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soccer–Basketball | |||||||

| CI | 249.73 | 38 | - | - | - | .949 | - |

| MI | 344.70 | 44 | 49.99 | 6 | .000 | .942 | .002 |

| SI | 358.18 | 47 | 63.48 | 9 | .000 | .940 | .009 |

| RI | 419.89 | 55 | 125.19 | 17 | .000 | .930 | .019 |

| Soccer–Handball | |||||||

| CI | 172.69 | 38 | - | - | - | .950 | - |

| MI | 183.30 | 44 | 10.60 | 6 | .101 | .948 | .002 |

| SI | 200.97 | 47 | 28.27 | 9 | .001 | .943 | .007 |

| RI | 247.46 | 55 | 74.76 | 17 | .000 | .928 | .022 |

| Soccer–Futsal | |||||||

| CI | 134.34 | 38 | - | - | - | .963 | - |

| MI | 143.63 | 44 | 9.28 | 6 | .158 | .962 | .001 |

| SI | 154.90 | 47 | 63.48 | 9 | .015 | .958 | .005 |

| RI | 170.55 | 55 | 125.13 | 17 | .004 | .955 | .008 |

| Basketball–Handball | |||||||

| CI | 274.86 | 38 | - | - | - | .941 | - |

| MI | 322.95 | 44 | 48.09 | 6 | .000 | .933 | .008 |

| SI | 336.40 | 47 | 61.55 | 9 | .000 | .931 | .010 |

| RI | 366.03 | 55 | 91.17 | 17 | .000 | .925 | .016 |

| Basketball–Futsal | |||||||

| CI | 236.49 | 38 | - | - | - | .951 | - |

| MI | 244.94 | 44 | 8.45 | 6 | .207 | .951 | .000 |

| SI | 267.68 | 47 | 31.18 | 9 | .000 | .946 | .005 |

| RI | 291.87 | 55 | 55.37 | 17 | .000 | .942 | .009 |

| Handball–Futsal | |||||||

| C | 114.40 | 38 | - | - | - | .951 | - |

| MI | 130.32 | 44 | 15.91 | 6 | .014 | .945 | .006 |

| SI | 139.82 | 47 | 25.42 | 9 | .003 | .941 | .010 |

| RI | 165.65 | 55 | 51.24 | 17 | .000 | .929 | .022 |

χ2 = chi-squared; df = degrees of freedom; Δχ2 = differences in the value of chi-squared; Δdf = differences in the degrees of freedom; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; ΔCFI = differences in the value of the Comparative Fit Index; CI= configural invariance; MI = measurement invariance; SI = scale invariance; RI = residual invariance

Discussion

Approaching the main goal of the present study, psychometric quality analysis of the MCSYSp (Borrego and Silva, 2012), as well as invariance analysis across gender and different sports, it is possible to affirm, in first instance, that the results demonstrated a negative and significant correlation between task and egoinvolving climate factors, which seems to counter the orthogonality of the underlying theoretical model (AGT: Nicholls, 1984). Nevertheless, similar results were found in the original version from which the instrument was translated and validated (Smith et al., 2008).

On the other hand, as Table 2 shows, the initial hypothesised model (two factors/12 items) did not adjust to the data in a satisfactory way; thus, after modification indexes analysis, two items of each factor were eliminated. In the case of the task-involving climate factor, the eliminated items were 7 and 11: ‘Coach said that all of us were important to the team’s success’ and ‘The coach told us that trying our best was the most important thing’, respectively. In the ego-involving climate factor, the eliminated items were 1 and 12: ‘Winning games was the most important thing for the coach’ and ‘Coach told us to try to be better than our teammates’, respectively.

As acknowledged, the decision about removing or not removing an item is not easy, and it is important to analyse if we should maintain the variables or not (Hair et al., 2014), always considering if we should maintain the theoretical model’s integrity (Henson and Roberts, 2006). The decision to eliminate the mentioned items was based on two fundamental aspects: 1) in practical terms, by questions related to the model’s estimation, it is not necessary to have 6 items to assess one latent factor, and good practices indicate four as recommended (Hair et al., 2014). This practice is common in some models with a lot of items to assess the same construct. For example, the PMCEQ case for the Portuguese population (Cid et al., 2012); 2) from a psychometric view, it is neither justifiable nor acceptable to maintain items with a factorial weight below .30 (Hair et al., 2014), which happens with the ego-involving climate factor’s items 1 and 12 and the task-involving climate factor’s item 11. Moreover, the fact that items (e.g., item 11) cause doubts from the semantic point of view (cross-loadings), in other words, that evoke ambiguity in their interpretation for the ones who answer, should not be maintained. For example, item 11 (‘The coach told us that trying our best was the most important thing’) could not be interpreted by the individuals as an observable variable that assesses exclusively the task-involving climate perception.

According to the AGT’s model (Nicholls, 1984), ‘trying our best’ (which implies effort) is not an exclusive characteristic of athletes who guide themselves to the task-involving climate. Athletes who guide themselves to the ego-involving climate can also ‘try their best’ to demonstrate competence in the activities they perform. The difference is that the former evaluates him- or herself by auto-referred criteria (i.e. they demonstrate competence depending on the knowledge they have of themselves), whereas the latter evaluates him- or herself by normative criteria (i.e. they demonstrate competence depending on what others do). In fact, approaching the evaluation of goal achievement theory (at the dispositional level), it is possible to find some criticism about the current measurement instruments TEOSQ (Task and Ego Orientation in Sport Questionnaire) and POSQ (Perception of Success Questionnaire), due to the confusion of conceptual definitions (i.e. task) with their correlates (e.g., effort, hard work) (Petherick and Markland, 2008), which are not exclusive of task orientation.

To summarise, the subjects can guide goals differently, which can lead behavioural patterns (i.e. adaptive or maladaptive), although it does not mean that individuals who are oriented towards the ego-involving climate cannot also experience the positive behaviours of practicing (Duda and Balaguer, 2007). However, this only happens when their competence perception is high, and they need to demonstrate more competence than others. After removing the referred items, the final model (two factors/eight items) adjusted to the data in a satisfactory way, showing good psychometric properties. Therefore, even though it is a shorter version, it is still consistent with the original model (Smith et al., 2008), and the observable variables (items) continue to reflect the latent variables that should supposedly assess, i.e. construct validity (Hair et al., 2014).

Furthermore, the MCSYSp presented adjustment values that were reasonable to the entire sample and to all samples (Table 2) by cutoff values adopted from the methodology (Marsh et al., 2004). Regarding internal consistency, high values of CR (≥.70) revealed that both factors measured the construct they intended to measure (Hair et al., 2014), as in the original version (Smith et al., 2008) and the Portuguese version (Borrego and Silva, 2012). In contrast, it was possible to verify minor problems concerning convergent validity in both factors, which means that items did not strongly converge to the factors. Nevertheless, all items had a factorial weight that was statistically significant in the respective factor, which, according to Hair et al. (2014), was a convergent validity indicator. Moreover, none of the items showed to be cross-loading, which also pointed out a convergent validity indicator (Byrne, 2010). Regarding discriminant validity, problems were not identified, which means the factors were distinct from each other, as the AGT’s model suggests (Nicholls, 1984).

In relation to the model’s invariance, results support measurement equivalence between gender and team sports; in other words, theoretical constructs underlying the questionnaire were conceptualised in the same way between gender and different team sports.

Thus, considering the assumptions from operationalised invariance analysis in the methodology (Byrne, 2010; Cheung and Rensvold, 2002), it is possible to affirm the following to both genders and team sports: configural invariance is verified as the same items group that explains the same factors group is maintained, independently of gender and team sport practiced; all factorial weights are invariant in both genders and team sports, which means items have the same importance as factors, independently of gender and/or team sports, and thus metric invariance is shown; the item intercepts are invariant (equivalents) in both genders and team sports, consequently representing scale invariance (i.e. strong invariance).

In this sense, when this assumption is proven, it means that the MCSYSp may be used to make real interpretations of athletes perception of the motivational climate induced by their coaches between genders and in the team sports analysed (Cheung and Rensvold, 2002); lastly, relatively to residual invariance, this assumption was almost never verified in the present study, except for soccer–futsal and basketball–futsal. However, according to Cheung and Rensvold (2002), it seems there is no consensus in literature about the relevance of residual invariance (i.e. strict invariance) analysis, and its analysis is considered optional by some researchers. Beyond this, according to Byrne (2010), the consensus failure related to this type of invariance is considered to be too restrictive, since it implies factorial weights, intercepts, and variance and covariance of waste do not differ significantly, which is too hard to reach in the social sciences. This fact, however, is not an indicator of lack of invariance of the model (Cheung and Rensvold, 2002).

Referring to swimming, invariance assumptions were not verified, which means that swimmers could perceive the motivational climate in a different manner compared to athletes from other studied team sports; in other words, the results show that the same items group associated to the respective latent factors is not perceived in the same manner in swimming compared to other team sports (in order to understand if the minor change/adaptation interfered with the absence of invariance between swimming and team sports, we analysed the invariance assumptions in a model without item 10 (two factors, seven items); the results from this analysis allowed to conclude that it was not the change/adaptation that interfered with the absence of invariance between swimming and team sports, since the model continued to be noninvariant.) Consequently, eventual inferences about the differences between swimmers and athletes from other sports cannot be precisely formulated (Cheung and Rensvold, 2002). This seems to be linked to the specific character of each sport. Since swimming is an individual sport, the athlete is responsible for the formulation of strategy needed to assure his or her own success, whereas the athletes from team sports must work together for success; thus, motivation (including motivational climate perception) appears to be the most important variable in the differentiation between team and individual sports (Keegan et al., 2011).

This explanation seems to gain strength if the specificity of our swimming sample is considered regarding years of practice, since the swimmers who participated in this study had a minimum of 6 and a maximum of 14 years of training experience (which was not the case in other sports), allowing them to be considered experienced athletes in their sports discipline. Thus, they were not to value items associated to the ego-involving climate factor (e.g. ‘the coach told us which players on the team were best’). Some studies (Cervelló et al., 2007; Jõesaar et al., 2011) have demonstrated that athletes with many years of practice in accomplishment contexts orient themselves more toward a task, whereby this orientation is linked to more self-determinant motivation and more adaptive behaviour patterns. This issue should be better analysed in future studies that could focus on invariance related to different years of training experience.

In conclusion, our intention was to analyse the psychometric properties of a questionnaire that would allow, in a clear and objective way, to assess the two dimensions used by the AGT in the sports context, contributing to the dissemination of knowledge in this area, however, it is known that validation studies of an instrument are a continuous process that takes time. Thus, the results presented in our study contribute to the increase of evidence that supports the use of this instrument in other sports, as it was suggested by Borrego and Silva (2012).

Therefore, taking into consideration the results of the current study, it is possible to conclude that the MCSYSp is a valid, reliable and transversal tool with regard to genders and several sports in order to assess the perception athletes have about the motivational climate in view of the success or failure criteria that are inherent to the sport accomplishment context. Nevertheless, we recommend conducting further studies with this scale in other individual sports, including invariance model analysis, in order to better understand its psychometric properties.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology and the European Union (UID/DTP/04045/2013; POCI-01-0145-FEDER-006969)

References

- Ames C. Achievement goals, motivational climate, and motivational processes. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1992. pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle S. Enhancing Motivation in Physical Education. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2001. pp. 101–127. [Google Scholar]

- Borrego C, Silva C.. Psychometric properties of the basketball Portuguese version of the motivational climate scale for youth sports. Cuad Psicol Deporte. 2012;12:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B. Structural equation modeling with EQS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cervelló E, Escartí A, Gúzman J.. Youth sport dropout from the achievement goal theory. Psicothema. 2007;19:65–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung G, Rensvold R.. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct Equ Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Cid L, Moutão J, Leitão J, Alves J.. Translation and validation of the exercise adaptation of the Perceived Motivational Climate Sport Questionnaire. Motriz. 2012;18:708–720. [Google Scholar]

- Duda J. Achievement goal research in sport: Pushing the boundaries and clarifying some misunderstandings. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2001. pp. 129–182. [Google Scholar]

- Duda J, Balaguer I. The coach-created motivational climate. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics: 2007. pp. 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Duda J, Ntoumanis N. After-school sport for children: Implications of a task involving motivational climate. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2005. pp. 311–330. [Google Scholar]

- Duda J, Whitehead J. Measurement of Goal Perspectives in Physical Domain. Morgantown: Fitness Technology Inc: 1998. pp. 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gould D, Flett R, Lauer L.. The relationship between psychosocial development and the sports climate experienced by underserved youth. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2012;13:80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hair J, Black W, Babin B, Anderson R. Multivariate data analysis. 7th. New Jersey: Pearson Educational; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harris B, Blom L, Visek A.. Assessment in Youth Sport: Practical Issues and Best Practice Guidelines. The Sport Psychol. 2013;7:201–211. doi: 10.1123/tsp.27.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson R, Roberts J.. Use of exploratory factor analysis in published research: Common errors and some comment on improved practice. Educ Psychol Meas. 2006;66:393–416. [Google Scholar]

- Federated sports athletes: total by sport federations. 2015. Nov, 2016. Instituto Português Desporto e Juventude (IPDJ)www.pordata.pt/portugal Available at. Accessed on. [Google Scholar]

- Jõesaar H, Hein V, Hagger M.. Peer influence on youth athletes need satisfaction, intrinsic motivation and persistence in sport: A 12-month prospective study. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2011;12:500–508. [Google Scholar]

- Keegan RJ, Spray C, Harwood C, Lavallee D. From ‘motivational climate’ to ‘motivational atmosphere’: A review of research examining the social and environmental influences on athlete motivation in sport. New York: Nova Science Publications; 2011. pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh H, Hau K, Wen Z.. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct Equ Modeling. 2004;11:320–341. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Murcia J, Blanco M, Galindo C, Villodre N, Coll D.. Preliminary validation of the scale of perception of motivational climate of equals (CMI) and the scale goal orientations in the year (GOES) with Spanish practitioners’ physical and sports activities. Rev Ibam Psicol Ejer Dep. 2006;1:13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Newton ML, Duda J, Yin ZN.. Examination of the psychometric properties of the Perceived Motivational Climate in Sport Questionnaire-2 in a sample of female athletes. J Sports Sci. 2000;18:275–290. doi: 10.1080/026404100365018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls J.. Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychol Rev. 1984;91:328–346. [Google Scholar]

- Ntoumanis N, Vazou S.. Peer motivational climate in youth sport: Measurement development and validation. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2005;27:432–455. [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou A.. Student’s perceptions of the physical education class environment for boys and girls and the perceived motivational climate. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1998;69:267–275. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1998.10607693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petherick C, Markland D.. The development of a goal in exercise measure (GOEM) Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2008;12:55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts G. Understanding the dynamics of motivation in physical activity: The influence of achievement goals on motivational processes. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2001. pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rutten EA, Schuengel C, Dirks E, Stams GJ, Biesta GJ, Hoeksma JB.. Predictors of antisocial and prosocial behavior in an adolescent sports context. Soc Dev. 2011;20:294–315. [Google Scholar]

- Sass DA.. Testing measurement invariance and comparing latent factor means within a confirmatory factor analysis framework. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2011;29:347–363. [Google Scholar]

- Smith R, Cumming S, Smoll F.. Development and validation of the Motivational Climate Scale for youth sports. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2008;20:116–136. [Google Scholar]