Abstract

Background

The main indication for carotid endarterectomy (CEA) is severity of carotid artery stenosis, even though most strokes in carotid disease are embolic. The relationship between carotid plaque volume (CPV) and symptoms of cerebral ischaemia, and the measurement of CPV by minimally invasive tomographic ultrasound imaging, were investigated.

Methods

The volume of the endarterectomy specimen was measured using a validated saline suspension technique in patients undergoing CEA. Time from last symptom and severity of stenosis measured by duplex ultrasonography were recorded. Middle cerebral artery emboli were counted using transcranial Doppler imaging (TCD) in a subset of patients.

Results

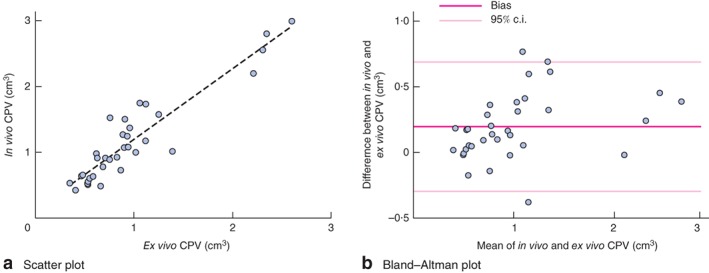

Some 339 patients were included, 270 with symptomatic and 69 with asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Mean(s.d.) CPV was higher in symptomatic than in asymptomatic patients (0·97(0·43) versus 0.74(0·41) cm3; P < 0·001). CPV did not correlate with severity of carotid stenosis (P = 0·770). Mean CPV was highest at 1·03(0·46) cm3 in the 4 weeks following cerebral symptoms, declining to 0·78(0·36) cm3 beyond 8 weeks. Among 33 patients who had TCD, mean CPV was 1·00(0·48) cm3 in the 27 patients with ipsilateral cerebral emboli compared with 0·67(0·16) cm3 in those without (P = 0·142). There was excellent correlation between CPV measured by tomographic ultrasound imaging and the endarterectomy specimen in 34 patients (r = 0·93, P < 0·001).

Conclusion

CPV correlated with symptoms of cerebral ischaemia, but not carotid stenosis. It could be a potential indicator for CEA.

Short abstract

Potential indication for treatment

Introduction

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the Western world behind ischaemic heart disease and cancer. It is the leading cause of disability in the UK, affecting over 150 000 people per year and costing the UK economy around £7 billion (€7·7 billion; exchange rate 14 August 2017) each year1, 2. Carotid disease causes 30 per cent of ischaemic strokes3, although most strokes are caused by atheroembolism. The principal indication for operation on carotid disease remains the severity of stenosis4, 5, 6, 7, 8. To confer maximal benefit, carotid endarterectomy (CEA) should be performed as soon as possible following symptoms of cerebral ischaemia, and certainly within 2 weeks as 43 per cent of patients suffering stroke had a transient ischaemic attack (TIA) in the preceding 7 days. Patients with 70–99 per cent stenosis have an absolute risk reduction of 23 per cent when CEA is performed within 2 weeks4, 5, 9, 10. Although recent symptoms of cerebral ischaemia are a clear indication for early carotid surgery, severity of stenosis alone is a poor predictor of stroke risk as asymptomatic patients with greater than 70 per cent carotid stenosis on best medical care have an ipsilateral stroke risk of under 2 per cent per year6, 11.

Carotid plaque volume (CPV) is the equivalent of atherosclerotic burden and is measured as the volume of atherosclerotic material within a defined length of artery. That stenosis is not inevitable in severe atherosclerotic arterial disease has been known for many years12. The importance of atherosclerotic burden has been emphasized in studies13, 14, 15 reporting substantial plaque burden in angiographically normal arteries; American Heart Association type VI (severe complex) lesions were frequently found in carotid arteries with less than 50 per cent stenosis. The PROSPECT study16 of coronary atherosclerosis demonstrated that cardiac events were related to high atherosclerotic burden rather than the severity of coronary artery stenosis. It is now accepted that atherosclerotic burden in coronary arteries is more important than stenosis in predicting subsequent cardiovascular events17, 18, 19, 20, 21.

Two recent MRI studies22, 23 of carotid plaque burden have underlined the importance of CPV in patients undergoing CEA within days of acute ischaemic stroke24. Patients randomized to early surgery after acute stroke had large‐volume unstable plaques, often discharging atherosclerotic material and very different from plaques removed at elective CEA24.

The aim of this study was to explore the relationship between CPV and symptoms of cerebral ischaemia in patients undergoing CEA. A method to measure CPV accurately in CEA specimens was developed, and the relationship between CPV, the severity of carotid stenosis and recent symptoms of cerebral ischaemia was explored in patients undergoing CEA. The relationships between CPV measured in the endarterectomy specimen and CPV measured by new tomographic ultrasound imaging (tUS) technology and middle cerebral artery emboli counts before surgery were also explored in subgroups of these patients.

Methods

Patients undergoing primary CEA in Greater Manchester were recruited. Local ethics committee approval was obtained, with informed consent in writing obtained from all patients. Patients with atrial fibrillation, a diagnosis or treatment for cancer within 6 months, or unable to give informed consent were excluded.

A detailed medical history was taken, recording cardiovascular risk factors and the timing and nature of any symptoms of cerebral ischaemia. Patients were classified as symptomatic if they had symptoms of cerebral ischaemia in the previous 6 months. Symptoms were further divided into stroke, TIA or amaurosis fugax using established criteria25. For symptomatic patients, the time between the onset of the most recent symptom and CEA was also recorded; patients were subdivided into groups with an interval of less than 2 weeks (0–13 days), 2–4 weeks (14–27 days), 4–8 weeks (28–55 days) and at least 8 weeks (56 days or more). The severity of carotid stenosis was measured using peak systolic flow velocity (PSV) on duplex Doppler ultrasound imaging, based on the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) criteria26, 27.

In addition to routine preoperative duplex imaging, a subset of patients underwent tUS within 24 h before surgery, performed by an experienced vascular scientist blinded to the clinical details. A magnetically tracked freehand three‐dimensional (3D) ultrasound system (Curefab, Munich, Germany) was attached to a Philips iu22 duplex machine (Philips, Bothell, Washington, USA). Sensors attached to the transducer tracked the transducer orientation and position in time and space. Multiplanar reconstructions were computed to produce 3D ultrasound volumes. System accuracy had been proven previously with phantom studies registered with CT and MRI28. CPV was calculated by tracing the luminal surface and the adventitia at an interslice distance of 1 mm. Multiple slices were created along the length of the carotid plaque, over the same length subsequently measured following endarterectomy, and a CPV calculated automatically. There was no attempt to differentiate between plaques mainly involving the bifurcation and those solely within the internal carotid artery. All measurements were repeated by a vascular laboratory scientist and the research fellow; both were trained in the technique, and were blinded to the patient's symptoms and each other's results.

Preoperative transcranial Doppler (TCD) insonation of the ipsilateral middle cerebral artery to count microemboli over 1 h was undertaken in a subgroup of patients less than 24 h before CEA. Microembolic signals were counted by two trained and blinded observers using the 1995 international consensus criteria29. Transient, unidirectional signals occurring within the Doppler spectrum, at least 3 dB higher than the background blood flow and lasting less than 300 ms, were counted as emboli.

During CEA, the surgeon was asked to pay particular attention to ensure that the entire carotid plaque specimen was removed en bloc, where possible. A member of the research team was present to collect the plaque in a dry pot on ice immediately after endarterectomy to minimize disruption before measuring CPV within the next hour. The full length of the endarterectomy plaque was recorded before the plaque was weighed while suspended below the surface of 110 ml normal saline in a 150‐ml polythene beaker placed on an electronic balance. The volume was calculated by dividing the suspended weight by the density of saline at 23 °C. Intraobserver agreement on the measurement of CPV, using data from the first 81 patients, demonstrated a mean bias of only 0·01 cm3 (95 per cent limits of agreement –0·11 to 0·14 cm3). Interobserver agreement for CPV had a mean bias of 0·004 cm3 (95 per cent limits of agreement –0·18 to 0·19 cm3). These demonstrate good reliability and repeatability for the measurement of CPV.

Statistical analysis

Normality of variables was assessed on the basis of skewness and kurtosis measures. Descriptive statistics for CPV are presented as mean(s.d.). Student's t tests and χ2 tests were used to compare patient characteristics and CPV values between asymptomatic and symptomatic patients. Differences in CPV between the symptom subgroups and at each time interval following the most recent symptoms of cerebral ischaemia were assessed using ANOVA, followed by Scheffé's multiple comparison test. Interobserver and intraobserver agreements for CPV measurement using the suspension hydrostatic weighing technique and tUS images were investigated using the Bland–Altman method of agreement. The conventional two‐sided 5 per cent significance level was used for all analyses.

Results

A total of 345 patients were recruited to the study but the endarterectomy specimens in six were removed piecemeal, rendering CPV measurements impossible. This left a total of 339 patients, all with carotid stenosis over 50 per cent (270 symptomatic, 69 asymptomatic) (Table 1). Symptomatic patients were more likely also to have had a previous episode of cerebral ischaemia (P = 0·035). There were no significant differences in cardiovascular risk factors between asymptomatic and symptomatic patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy

| Asymptomatic (n = 69) | Symptomatic (n = 270) | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 69·6(8·7) | 70·6(8·7) | 0·370‡ |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 27·2(4·1) | 27·1(4·9) | 0·905‡ |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 47 : 22 | 177 : 93 | 0·661 |

| Diabetes | 13 (19) | 50 (18·5) | 0·953 |

| Hypertension | 54 (78) | 201 (74·4) | 0·597 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 55 (80) | 188 (69·6) | 0·177 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 14 (20) | 63 (23·3) | 0·556 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 12 (17) | 39 (14·4) | 0·567 |

| Previous stroke | 22 (32) | 52 (19·3) | 0·035 |

| Smoking history | 0·979 | ||

| Smoker | 16 (23) | 62 (23·3) | |

| Ex‐smoker | 38 (55) | 138 (51·1) | |

| Never smoked | 13 (19) | 47 (17·4) | |

| Missing | 2 (3) | 23 (8·5) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless otherwise indicated;

values are mean(s.d.).

χ2 test, except

Student's t test.

Total mean(s.d.) CPV was significantly greater in men than in women (1·01(0·45) versus 0·76(0·34) cm3 respectively; P < 0·001). Cardiovascular risk factors were not otherwise significantly related to CPV (Table 2). CPV was not associated with the severity of carotid stenosis in these patients, in whom the severity of stenosis was the indication for CEA (P = 0·770) (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Relationship between carotid plaque volume and cardiovascular risk factors

| n | Carotid plaque volume* | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | < 0·001 | ||

| M | 221 | 1·01(0·45) | |

| F | 118 | 0·76(0·34) | |

| Diabetes | 62 | 0·95(0·42) | 0·772 |

| Hypertension | 252 | 0·93(0·44) | 0·573 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 240 | 0·94(0·43) | 0·728 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 76 | 0·97(0·49) | 0·456 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 50 | 0·97(0·49) | 0·490 |

| Previous stroke | 72 | 0·88(0·42) | 0·251 |

| Smoker | 78 | 0·93(0·51) | 0·650 |

Values are mean(s.d.).

Versus carotid plaque volume in absence of risk factor (Student's t test).

Figure 1.

Mean(s.d.) carotid plaque volume (CPV) in patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy according to severity of stenosis. P = 0·770 (ANOVA, followed by Scheffé's multiple comparison test)

Mean CPV was significantly greater in the 270 symptomatic patients than in the 69 patients with no symptoms of cerebral ischaemia (0·97(0·43) versus 0·74(0·41) cm3; P < 0·001). The difference remained significant following adjustment for sex (P < 0·001). The mean CPV was 1·03(0·49) cm3 in 93 patients following recent stroke, compared with 0·95(0·42) cm3 for the 141 patients who had a TIA and 0·91(0·28) cm3 for the 34 patients with amaurosis fugax (P = 0·254); the symptom was not recorded for two patients.

Among the 270 symptomatic patients, mean CPV was highest in patients undergoing CEA shortly after symptoms of cerebral ischaemia and declined as the interval between symptoms and surgery increased (P < 0·001) (Fig. 2). Mean CPV for patients undergoing CEA within 2 weeks of symptoms (1·039 cm3) was very similar to that among patients undergoing CEA within 2–4 weeks (1·035 cm3), so these patients were grouped together for statistical analysis. Mean CPV within 4 weeks following symptoms of cerebral ischaemia was 1·03(0·46) cm3 compared with 0·95(0·24) cm3 between 4 and 8 weeks, and 0·78(0·36) cm3 more than 8 weeks after symptoms. Those who underwent CEA more than 8 weeks following symptoms of cerebral ischaemia had a CPV almost identical to that of asymptomatic patients, but significantly lower than that in patients undergoing CEA less than 4 weeks after symptoms (P = 0·001, Scheffé's multiple comparison test).

Figure 2.

Mean(s.d.) carotid plaque volume (CPV) in patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy within 2, 2 and less than 4, 4–8 and more than 8 weeks following the most recent symptom of cerebral ischaemia. P < 0·001 (ANOVA, followed by Scheffé's multiple comparison test)

Using PSV as a measure of the haemodynamic severity of stenosis, there were no corresponding differences. Mean(s.d.) PSV was 3·49(1·84) cm/s within 4 weeks of symptoms, 3·88(2·13) cm/s between 4 and 8 weeks, and 3·47(2·09) cm/s more than 8 weeks after the onset of the most recent symptom of cerebral ischaemia (P = 0·570). Mean PSV was higher in asymptomatic patients undergoing CEA than it was in symptomatic patients (3·99(1·77) versus 3·47(1·94) cm/s respectively; P = 0·056), although this is probably because many surgeons were reluctant to undertake CEA for asymptomatic disease unless the severity of the stenosis exceeded 80 per cent.

Cerebral emboli were counted in the ipsilateral middle cerebral artery over 1 h by TCD before CEA in 33 symptomatic patients. They were detected in 27 of these patients, the mean(s.d.) number of emboli during the hour of monitoring being 3·9(2·7). Mean CPV was 1·00(0·48) cm3 in the 27 patients with cerebral emboli compared with 0·67(0·16) cm3 among the six patients in whom no cerebral emboli were detected (P = 0·142). There was a significant but weak correlation between number of cerebral emboli per h and CPV (r = 0·36, P = 0·045). There was a negative but insignificant correlation between number of cerebral emboli per h and PSV (r = –0·255, P = 0·190).

Of 50 patients who underwent preoperative tUS, results from ten were omitted owing to extensive acoustic shadowing rendering interpretation impossible, and six did not have corresponding surgical specimens. The CPV measured by tUS in the remaining 34 patients correlated closely with the CPV measured in the endarterectomy specimen (r = 0·93, P < 0·001), with minimal bias (0·20 (95 per cent c.i. –0·29 to 0·69) cm3) (Fig. 3). Inter‐rater analysis demonstrated minimal bias (0·01 (–0·23 to 0·25) cm3) between the CPV measurements calculated by the two observers, again with excellent correlation (r = 0·98, P < 0·001) (data not shown). Intrarater analysis demonstrated minimal bias (0·07 (0·25 to 0·39) cm3) between the CPV measurements calculated when repeated by the primary observer, again with excellent correlation (r = 0·97, P < 0·001) (data not shown).

Figure 3.

a Scatter plot demonstrating correlation between in vivo measurements of carotid plaque volume (CPV) by three‐dimensional ultrasonography and ex vivo measurements using the immersion technique (r = 0·93, P < 0·001). b Bland–Altman plot (mean(s.d.) bias 0·20 (95 per cent c.i. –0·29 to 0·69) cm3)

Discussion

CPV in the endarterectomy specimen was associated with recent symptoms of cerebral ischaemia in patients undergoing CEA. Perhaps more importantly, CPV was markedly higher in the first few weeks following symptoms of cerebral ischaemia, when the risk of stroke is also known to be high. Rothwell and colleagues10 clearly showed that CEA had the greatest impact on stroke risk if undertaken within days of cerebral ischaemia, and no more impact than it had for asymptomatic patients if undertaken more than 12 weeks following symptoms.

The results suggest that the healing of carotid plaques, following what is presumed to be a discharge of atherosclerotic material at the time of cerebral ischaemia, may be faster than previously recognized. The decline in plaque volume over time following symptoms of cerebral ischaemia was not associated with any significant change in the severity of carotid stenosis. There was no significant relationship between the severity of stenosis and CPV, although this is a population of patients in whom the severity of carotid stenosis was sufficient to justify CEA. It was hardly surprising that the severity of carotid stenosis was marginally higher in the asymptomatic patients as many surgeons are reluctant to undertake carotid endarterectomy in asymptomatic patients unless there is stenosis exceeding 80 per cent.

Middle cerebral artery emboli in patients with carotid disease are known to be associated with recurrent ischaemic events30. The Asymptomatic Carotid Emboli Study31 demonstrated that the annual risk of stroke in patients with embolic signals was 3·6 per cent compared with 0·7 per cent in those without. The significant correlation between CPV and number of cerebral emboli suggests that CPV may be a measure of stroke risk. The absence of a correlation between cerebral emboli and severity of stenosis underlines the low risk of stroke in asymptomatic severe carotid stenosis. Although there has been little previous research on CPV, when measured by ultrasound imaging in 349 patients it was associated with the frequency of subsequent stroke, TIA and death32. Both CPV and changes in plaque composition were also reported to be indicators of stroke risk33.

The concept of the vulnerable plaque was first reported in coronary artery disease, where ruptured, inflammatory and thin cap plaques were associated with acute coronary syndrome34, 35, 36. The same was assumed to be true for carotid plaques, leading to many attempts to identify carotid plaque characteristics that relate to the subsequent risk of stroke22, 23, 37, 38, 39. The present results raise the intriguing possibility that intraplaque haemorrhage37 and measures of plaque perfusion38, 40 may be the consequence of plaque rupture, rather than risk factors for future stroke. The finding that CPV declines with time following symptoms of cerebral ischaemia suggests a healing process measured in weeks, which may be much shorter than that suggested in the literature. It is possible that, following the discharge of atherosclerotic material from a carotid plaque, the space is filled with blood which has been interpreted as intraplaque or subplaque haemorrhage. Subsequently this haematoma is lysed and progressively replaced by granulation tissue as part of the healing process, with resulting increases in plaque perfusion38. The fact there is no difference between CPV within 2 weeks of symptoms and that at 2–4 weeks is consistent with the time required for a haematoma to start to resolve by lysis, and for the resulting inflammation to settle.

Previous studies33, 41, 42 measuring CPV by both MRI and CT suggested that CPV was associated with cardiovascular risk factors and symptoms of cerebral ischaemia. If the accuracy of tUS measurement of CPV is confirmed in larger studies, it is possible that the measurement of CPV could replace severity of stenosis as the principal indication for CEA. The ultimate objective could be population screening for carotid disease. 3D ultrasound techniques for the measurement of CPV need to be explored with this in mind43, 44, 45.

Limitations of this study were that only 33 patients of the intended 50 underwent preoperative TCD to detect middle cerebral artery emboli. Neither CT nor MRI of the brain is routine in patients undergoing CEA in Manchester, precluding any investigation of the relationship between CPV and cerebral infarction. The need for urgent CEA following symptoms of cerebral ischaemia has been established by two major meta‐analyses46, 47 demonstrating that the risk of stroke is highest immediately following TIA and then declines over a similar timescale. These studies showed that the stroke risk within 1 week of TIA was approximately 10 per cent and that this risk declined progressively, such that the risk was no higher than in patients with asymptomatic carotid disease by 12 weeks. As CPV declines following symptoms of cerebral ischaemia at a rate remarkably similar to the reduction in stroke risk, this is consistent with CPV being associated with stroke risk. Once a minimally invasive method for measuring CPV accurately in patients has been established, the relationship between CPV and stroke risk needs to be explored in a definitive cohort study.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. Morris for the statistical analyses. No preregistration exists for the studies reported in this article. All research was funded by the Manchester Surgical Research Trust (registered charity number 702313). The funding source had no involvement in the design, collection or interpretation of the data.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Presented in part to a meeting of the European Society for CardioVascular and Endovascular Surgery, Belgrade, Serbia, April 2016

References

- 1. Wolfe CDA. The impact of stroke. Br Med Bull 2000; 56: 275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Henry M, Polydorou A, Klonaris C, Henry I, Polydorou AD, Hugel M. Carotid angioplasty and stenting under protection. State of the art. Minerva Cardioangiol 2007; 55: 19–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Timsit SG, Sacco RL, Mohr JP, Foulkes MA, Tatemichi TK, Wolf PA et al Early clinical differentiation of cerebral infarction from severe atherosclerotic stenosis and cardioembolism. Stroke 1992; 23: 486–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet 1998; 351: 1379–1387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators ; Barnett HJM, Taylor DW, Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Peerless SJ, Ferguson GG et al Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high‐grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med 1991; 325: 445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, Peto C, Peto R, Potter J et al; MRC Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST) Collaborative Group . Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 363: 1491–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study . Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA 1995; 273: 1421–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liapis CD, Bell PR, Mikhailidis D, Sivenius J, Nicolaides A, Fernandes e Fernandes J et al; ESVS Guidelines Collaborators . ESVS guidelines. Invasive treatment for carotid stenosis: indications, techniques. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2009; 37(Suppl): 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP, Barnett HJ; Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists' Collaboration . Endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis in relation to clinical subgroups and timing of surgery. Lancet 2004; 363: 915–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, Fox AJ, Taylor DW, Mayberg MR et al; Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists' Collaboration . Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet 2003; 361: 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moneta GL, Taylor DC, Nicholls SC, Bergelin RO, Zierler RE, Kazmers A et al Operative versus nonoperative management of asymptomatic high‐grade internal carotid artery stenosis: improved results with endarterectomy. Stroke 1987; 18: 1005–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins CK, Stankunavicius R, Kolettis GJ. Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. N Engl J Med 1987; 316: 1371–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Babiarz LS, Astor B, Mohamed MA, Wasserman BA. Comparison of gadolinium‐enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance angiography with high‐resolution black blood cardiovascular magnetic resonance for assessing carotid artery stenosis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2007; 9: 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dong L, Underhill HR, Yu W, Ota H, Hatsukami TS, Gao TL et al Geometric and compositional appearance of atheroma in an angiographically normal carotid artery in patients with atherosclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010; 31: 311–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saam T, Underhill HR, Chu B, Takaya N, Cai J, Polissar NL et al Prevalence of American Heart Association type VI carotid atherosclerotic lesions identified by magnetic resonance imaging for different levels of stenosis as measured by duplex ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51: 1014–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, de Bruyne B, Cristea E, Mintz GS et al; PROSPECT Investigators . A prospective natural‐history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47(Suppl): C13–C18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Naghavi M, Libby P, Falk E, Casscells SW, Litovsky S, Rumberger J et al From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: a call for new definitions and risk assessment strategies: Part I. Circulation 2003; 108: 1664–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Naghavi M, Libby P, Falk E, Casscells SW, Litovsky S, Rumberger J et al From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: a call for new definitions and risk assessment strategies: Part II. Circulation 2003; 108: 1772–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ambrose JA, Tannenbaum MA, Alexopoulos D, Hjemdahl‐Monsen CE, Leavy J, Weiss M et al Angiographic progression of coronary artery disease and the development of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1988; 12: 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Glaser R, Selzer F, Faxon DP, Laskey WK, Cohen HA, Slater J et al Clinical progression of incidental, asymptomatic lesions discovered during culprit vessel coronary intervention. Circulation 2005; 111: 143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lindsay AC, Biasiolli L, Lee JM, Kylintireas I, MacIntosh BJ, Watt H et al Plaque features associated with increased cerebral infarction after minor stroke and TIA: a prospective, case–control, 3‐T carotid artery MR imaging study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2012; 5: 388–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhao X, Underhill HR, Zhao Q, Cai J, Li F, Oikawa M et al Discriminating carotid atherosclerotic lesion severity by luminal stenosis and plaque burden: a comparison utilizing high‐resolution magnetic resonance imaging at 3·0 Tesla. Stroke 2011; 42: 347–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Welsh S, Mead G, Chant H, Picton A, O'Neill PA, McCollum CN. Early carotid surgery in acute stroke: a multicentre randomised pilot study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2004; 18: 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Walker M III, Campbell BR, Azer K, Tong C, Fang K, Cook JJ et al A novel 3‐dimensional micro‐ultrasound approach to automated measurement of carotid arterial plaque volume as a biomarker for experimental atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2009; 204: 55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hathout GM, Fink JR, El‐Saden SM, Grant EG. Sonographic NASCET index: a new Doppler parameter for assessment of internal carotid artery stenosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26: 68–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oates CP, Naylor AR, Hartshorne T, Charles SM, Fail T, Humphries K et al Joint recommendations for reporting carotid ultrasound investigations in the United Kingdom. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2009; 37: 251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Feurer R, Hennersperger C, Runyan JB, Seifert CL, Pongratz J, Wilhelm M et al Reliability of a freehand three‐dimensional ultrasonic device allowing anatomical orientation ‘at a glance’: study protocol for 3D measurements with Curefab CS®. J Biomed Graph Comput 2012; 2: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Consensus Committee of the Ninth International Cerebral Hemodynamic Symposium . Basic identification criteria of Doppler microembolic signals. Stroke 1995; 26: 1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Siebler M, Kleinschmidt A, Sitzer M, Steinmetz H, Freund HJ. Cerebral microembolism in symptomatic and asymptomatic high‐grade internal carotid artery stenosis. Neurology 1994; 44: 615–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Markus HS, MacKinnon A. Asymptomatic embolization detected by Doppler ultrasound predicts stroke risk in symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Stroke 2005; 36: 971–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wannarong T, Parraga G, Buchanan D, Fenster A, House AA, Hackam DG et al Progression of carotid plaque volume predicts cardiovascular events. Stroke 2013; 44: 1859–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rozie S, de Weert TT, de Monyé C, Homburg PJ, Tanghe HL, Dippel DW et al Atherosclerotic plaque volume and composition in symptomatic carotid arteries assessed with multidetector CT angiography; relationship with severity of stenosis and cardiovascular risk factors. Eur Radiol 2009; 19: 2294–2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Virmani R, Burke A, Farb A. Coronary risk factors and plaque morphology in men with coronary disease who died suddenly. Eur Heart J 1998; 19: 678–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Davies MJ, Thomas AC. Plaque fissuring – the cause of acute myocardial infarction, sudden ischaemic death, and crescendo angina. Br Heart J 1985; 53: 363–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1685–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Altaf N, Daniels L, Morgan PS, Auer D, MacSweeney ST, Moody AR et al Detection of intraplaque hemorrhage by magnetic resonance imaging in symptomatic patients with mild to moderate carotid stenosis predicts recurrent neurological events. J Vasc Surg 2008; 47: 337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Demarco JK, Ota H, Underhill HR, Zhu DC, Reeves MJ, Potchen MJ et al MR carotid plaque imaging and contrast‐enhanced MR angiography identifies lesions associated with recent ipsilateral thromboembolic symptoms: an in vivo study at 3T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010; 31: 1395–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yuan C, Zhang SX, Polissar NL, Echelard D, Ortiz G, Davis JW et al Identification of fibrous cap rupture with magnetic resonance imaging is highly associated with recent transient ischemic attack or stroke. Circulation 2002; 105: 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goldstein LB, Adams R, Alberts MJ, Appel LJ, Brass LM, Bushnell CD et al Primary prevention of ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council: cosponsored by the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Interdisciplinary Working Group; Cardiovascular Nursing Council; Clinical Cardiology Council; Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism Council; and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group : the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline. Stroke 2006; 37: 1583–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhao H, Zhao X, Liu X, Cao Y, Hippe DS, Sun J et al Association of carotid atherosclerotic plaque features with acute ischemic stroke: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Eur J Radiol 2013; 82: e465–e470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nandalur KR, Hardie AD, Raghavan P, Schipper MJ, Baskurt E, Kramer CM. Composition of the stable carotid plaque: insights from a multidetector computed tomography study of plaque volume. Stroke 2007; 38: 935–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kalashyan H, Saqqur M, Shuaib A, Romanchuk H, Nanda NC, Becher H. Comprehensive and rapid assessment of carotid plaques in acute stroke using a new single sweep method for three‐dimensional carotid ultrasound. Echocardiography 2013; 30: 414–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Landry A, Spence JD, Fenster A. Measurement of carotid plaque volume by 3‐dimensional ultrasound. Stroke 2004; 35: 864–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Landry A, Spence JD, Fenster A. Quantification of carotid plaque volume measurements using 3D ultrasound imaging. Ultrasound Med Biol 2005; 31: 751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Giles MF, Rothwell PM. Risk of stroke early after transient ischaemic attack: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Neurol 2007; 6: 1063–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. CM Wu, McLaughlin K, Lorenzetti DL, Hill MD, Manns BJ, Ghali WA. Early risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167: 2417–2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]