Selection on the basis of physiological traits is hedged with obstacles in conventional breeding programmes – it is a little-explored concept. However, in this issue of Journal of Experimental Botany (pages 861–872), Jackson et al. present research in which the broad-sense heritability of leaf- and crop-level transpiration efficiency was tested within the framework of Australia’s main sugarcane breeding programme.

Conventional breeding mostly consists of large-scale crosses followed by quick selection methods. To date, most breeding programmes do not use physiological indices, while some rely on experienced breeders walking through field or nursery trials and visually selecting the winners for the following stages. Further, breeders mostly select for vigour and disease resistance. Therefore, selecting for physiological traits, particularly something as complex as transpiration efficiency (TE), is deemed unworkable. The main obstacles include physiological traits often being complex, time-consuming to measure, subject to significant genotype–environment interactions, not clearly linked to genetic markers, and with their broad or narrow sense heritability weak or untested.

The key contribution of the study by Jackson et al. (2016) stems from the authors’ attempt to devise the least number of leaf gas exchange measurements required to infer statistically meaningful conclusions about variation and heritability in leaf TE, and the link with plant TE and yield in sugarcane. The main findings were significant genetic variations in plant TE and intrinsic leaf TE as measured by leaf intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci); high broad-sense heritability for mean Ci (0.81); and Ci having a strong genetic correlation (–0.92) with plant TE at mid-range stomatal conductance (gs).

Physiological definitions and variations of leaf transpiration efficiency

According to Fick’s law,

| (1) |

where A and E are the rates of leaf CO2 assimilation and transpiration (H2O), Ci and Ca are the leaf intercellular and ambient CO2 partial pressures, and ei and ea are the water vapour pressures inside the leaf and in the surrounding air, respectively. In addition, , where and refer to the stomatal conductance for CO2 and water vapour, respectively; and 1.6 is the ratio of binary diffusivity of water vapour to that of CO2 in air (Farquhar et al., 1989).

Accordingly, leaf-level TE (TEL) is given by:

| (2) |

Assimilation rates depend on both gs and photosynthetic biochemistry, while transpiration rates depend on boundary layer conductance, gs and the leaf-to-air vapour pressure difference, which in turn depends on leaf temperature and the relative humidity of the surrounding air. Hence, this expression of TE is not ideal in screening for genetic differences because it is highly dependent on environmental conditions. A better expression that reflects a genotype-level trait is intrinsic TE (TEi), given by:

| (3) |

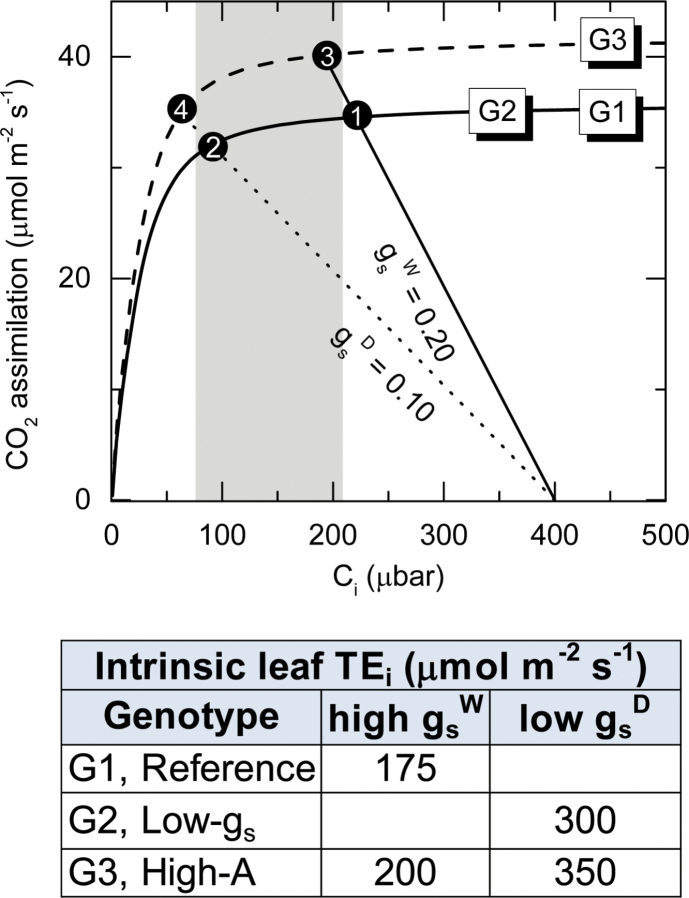

Reduced gs leads to lower Ci and Ci/Ca, which represents an integrative parameter of TEi, reflecting changes in both A and gs (equation 3). The contrasting influence of improved photosynthesis and reduced stomatal conductance on TEi is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Modelled responses of C4 photosynthesis to changes in Ci at 25oC and saturating irradiance according to von Caemmerer et al. (2000). The modelling depicts three hypothetical genotypes. G1 (continuous line) and G3 (broken line) possess different photosynthetic capacity. G2 (continuous line) has similar photosynthetic capacity to G1, but operates with lower gs.

Within each scenario, reduced gs (due to low-gs genotype or dry soil or air) increases TEi at the expense of reduced A. Accordingly, TEi increases by 73% while A decreases by 13%, when moving from points 2 to 1 (filled circles) in G1 and from 3 to 4 (filled circles) in G3; gs decreases by 50%.

Greater photosynthetic capacity in G3, relative to G1 and G2 genotypes, leads to increased TEi at any given gs. G3 is the desirable genotype because it can potentially fix more CO2 in wet (e.g. high gsW) or dry (e.g. low gsD) conditions.

The shaded area represents the ideal (Ci) conditions under which genotypic screening gives the best population estimates of TEi according to Jackson et al. (2016). At higher Ci, A is no longer sensitive to changes in gs. At lower Ci, A is highly sensitive to Ci giving erroneous estimates of TEi; or reduced gs may be due to water stress, in which case Ci rises due to photosynthetic inhibition (Ghannoum, 2009), rendering TEi estimates unreliable.

Paradoxical relationship between crop yield and transpiration efficiency

Most rain-fed crops experience periods of water stress during the growing season. Hence, traits related to water use are critical for crop productivity and survival. Whole plant TE (TEP), the ratio of biomass produced to water used, is an important determinant of crop yield (Passioura, 1977), and crop yield (Y) can be expressed as:

| (4) |

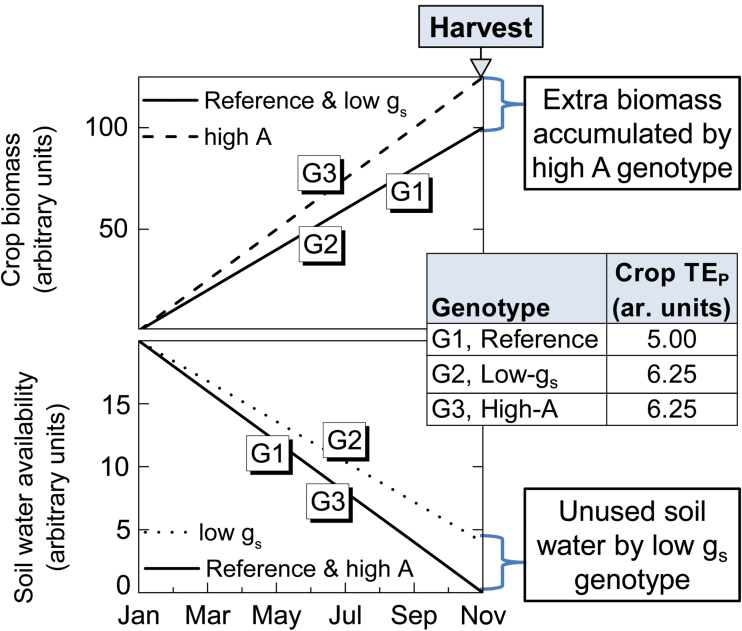

Greater TEP may potentially lead to greater crop yield only if improved TEP does not entail reduced water use. This is the case when improved TEP results from improved A rather than reduced gs. These contrasting scenarios are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of sugarcane biomass accumulation and soil water availability (or use) between transplanting and harvest dates in three hypothetical genotypes.

Within each scenario, reduced gs (due to low-gs genotype or dry soil or air) potentially increases TEP without contributing to increased biomass accumulation at harvest relative to the reference genotype, G1. Most inefficiently for both rain-fed or irrigated crops, low-gs genotypes or conditions imply that crops reach maturity without exhausting all available soil water at harvest, which translates into lower farm-level TE and productivity.

Greater photosynthetic capacity in G3 relative to G1 and G2 genotypes potentially leads to increased TEP and crop productivity at any stage during crop growth, including at harvest.

G3 is the desirable genotype because it theoretically leads to greater productivity and TEP in wet (high gs) or dry (low gs) conditions. In addition, the G3 genotype consumes all available soil water by harvest.

Sugarcane is a largely biomass crop, where harvest index is a fixed proportion of final biomass at harvest. This is not the case for grain crops, where traits and environmental conditions regulating the time of flowering and grain filling complicate the relationship between TEP, water use and crop yield. For example, grain crops that flower early may not have built enough biomass to fill lots of grains, while late-flowering crops may have too little water left in the soil during grain filling (Passioura, 2002). Hence, sugarcane is a crop where improved photosynthetic capacity will probably lead to greater potential crop yield.

Perspectives

For most crops, and particularly for biomass crops such as sugarcane, improved TE is a desirable trait as long as it does not compromise total crop water use, which ultimately drives crop productivity in water-limited environments. Water-use is determined by a myriad of traits, including TE, root architecture, biomass partitioning and tissue respiration, amongst others (Farquhar et al., 1989). Therefore, reporting good genetic correlations of leaf-level TEi with plant TE and yield (Jackson et al., 2016) is surprising, but good news for breeders and crop improvement.

Improved TEi without compromising productivity is essentially a quest for improved photosynthetic capacity. Jackson et al. (2016) honed in on Ci as both an integrator of TEi and a screening index, and have proposed that reduced Ci at any given stomatal conductance may result in improved yields in water-limited environments without compromising rates of crop water use and growth.

Finally, a word of caution. Given that atmospheric CO2 is rising and that Ca experienced by leaves in gas exchange cuvettes varies depending on photosynthetic capacity, amongst other factors, I suggest that Ci/Ca is a more suitable screening index than Ci (equation 3). Selecting for lowered Ci/Ca per stomatal conductance via breeding is highly desirable, especially for water-limited environments, and research should focus on developing low-cost, high-throughput screening tools that can be enticing for breeders.

References

- Farquhar GD, Ehleringer JR, Hubick KT. 1989. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 40, 503–537. [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum O. 2009. C4 photosynthesis and water stress. Annals of Botany 103, 635–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson P, Basnayake J, Inman-Bamber G, Lakshmanan P, Natarajan S, Stokes C. 2016. Genetic variation in transpiration efficiency and relationships between whole plant and leaf gas exchange measurements in Saccharum spp. and related germplasm. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 861–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passioura JB. 1977. Grain yield, harvest index, and water use of wheat. Journal of the Australian Institute of Agricultural Science 43, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Passioura JB. 2002. Environmental biology and crop improvement. Functional Plant Biology 29, 537–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S. 2000. Biochemical models of leaf photosynthesis . Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing. [Google Scholar]