Short abstract

This study is a comprehensive assessment of the quality of PTSD and depression care delivered by the Military Health System (MHS), including performance on 30 quality measures evaluating receipt of recommended assessments and treatments.

Keywords: Depression, Health Care Quality Measurement, Mental Health Treatment, Military Health and Health Care, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Abstract

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) strives to maintain a physically and psychologically healthy, mission-ready force, and the care provided by the Military Health System (MHS) is critical to meeting this goal. Attention has been directed to ensuring the quality and availability of programs and services for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression. This study is a comprehensive assessment of the quality of care delivered by the MHS in 2013–2014 for over 38,000 active-component service members with PTSD or depression. The assessment includes performance on 30 quality measures to evaluate the receipt of recommended assessments and treatments. These measures draw on multiple data sources including administrative encounter data, medical record review data, and patient self-reported outcome monitoring data. The assessment identified strengths and areas for improvement for the MHS. In particular, the MHS excels at screening for suicide risk and substance use, but rates of appropriate follow-up for service members with suicide risk are lower. Most service members received at least some psychotherapy, but less than half of psychotherapy delivered was evidence-based. In analyses focused on Army soldiers, outcome monitoring increased notably over time, yet preliminary analyses suggest that more work is needed to ensure that services are effective in reducing symptoms. When comparing performance between 2012–2013 and 2013–2014, most measures demonstrated slight improvement, but targeted efforts will be needed to support further improvements. RAND provides recommendations for strategies to improve the quality of care delivered for these conditions.

This study represents the third in a series of RAND studies about the quality of care for PTSD and depression in the MHS. At the request of DoD, the RAND Corporation initiated a project in 2012 to (1) provide a descriptive baseline assessment of the extent to which providers in the MHS implement care consistent with clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for PTSD and depression, and (2) examine the relationship between guideline-concordant care and clinical outcomes for these conditions. This study builds on two previous RAND studies, one that presented a set of quality measures developed for care provided to active-component service members with PTSD and depression (Hepner et al., 2015), and another that described characteristics of active-component service members who received care for PTSD or depression from the MHS and assessed the quality of care provided for PTSD and depression using quality measures based on 2012–2013 administrative data (Hepner et al., 2016).

This study provides a more comprehensive assessment of MHS outpatient care for active-component service members with PTSD and depression by including an expanded set of quality measures and using two new sources of data, medical records and symptom questionnaires. As in Phase I, we focus in this study on active-component service members to increase the likelihood that the care they received was provided or paid for by the MHS, rather than other sources of health care. Data from all three data sources were analyzed for the 2013–2014 time period—more recent than the time period used for the analyses in our previous study, which was 2012–2013 (Hepner et al., 2016). We describe the characteristics of active-component service members who received care for PTSD or depression from the MHS in 2013–2014 based on administrative data. We also assess the quality of care provided for PTSD and depression using quality measures based on three data sources for 2013–2014. Finally, we explore the use of symptom scores in the MHS and the relationship between adherence to guideline-concordant care and symptom scores; these analyses were limited to Army personnel who were seen in military treatment facility (MTF) behavioral health clinics, due to data availability.

Selecting Quality Measures for PTSD and Depression Care

Quality measures provide a way to measure how well health care is being delivered. Quality measures are applied by operationalizing aspects of care recommended by CPGs using administrative data, medical records, clinical registries, patient or clinician surveys, and other data sources. Such measures provide information about the health care system and highlight areas in which providers can take action to make health care safer and more equitable (National Quality Forum, 2017a and 2017b). Quality measures usually incorporate operationally defined numerators and denominators, and scores are typically presented as the percentage of eligible patients who received the recommended care (e.g., percentage of patients who receive timely outpatient follow-up after inpatient discharge). Based on previous work conducted by RAND, we selected 15 quality measures for PTSD and 15 quality measures for depression as the focus of this study. These measures are described in Table 1. These measures assess care described in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)/DoD CPG for the Management of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense, 2009) and Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Reaction (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense, 2010), including assessment of patients starting a new treatment episode, follow-up of positive suicidal ideation, adequate medication management, receipt of psychotherapy, receipt of a minimal number of visits associated with a first-line treatment (either psychotherapy or medication management), monitoring of symptoms over time, response to treatment, and follow-up after hospital discharge for a mental health condition. During this study, these two VA/DoD guidelines were in the process of being updated. The updated VA/DoD MDD guideline (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense, 2016) was made available shortly before this study was released, but the updated PTSD guideline had not yet been published.

Table 1.

Quality Measures for Patients with PTSD and Patients with Depression

| Measure No. | PTSD | Depression |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment | ||

| A1 | Percentage of PTSD patients with a new treatment episode with assessment of symptoms with PCL within 30 days | Percentage of depression patients with a new treatment episode with assessment of symptoms with PHQ-9 within 30 days |

| A2 | Percentage of PTSD patients with a new treatment episode assessed for depression within 30 days | Percentage of depression patients with a new treatment episode assessed for manic/hypomanic behaviors within 30 days |

| A3 | Percentage of PTSD patients with a new treatment episode assessed for suicide risk at same visit | Percentage of depression patients with a new treatment episode assessed for suicide risk at same visit* |

| A4 | Percentage of PTSD patients with a new treatment episode assessed for recent substance use within 30 days | Percentage of depression patients with a new treatment episode assessed for recent substance use within 30 days |

| Treatment | ||

| T1 | Percentage of PTSD patients with symptom assessment with PCL during 4-month measurement period | Percentage of depression patients with symptom assessment with PHQ-9 during 4-month measurement period* |

| T3 | Percentage of patient contacts of PTSD patients with SI with appropriate follow-up (PTSD-T3) | Percentage of patient contacts of depression patients with SI with appropriate follow-up (Depression-T3) |

| T5 | Percentage of PTSD patients with a newly prescribed SSRI/SNRI with an adequate trial (≥ 60 days) | Percentage of depression patients with a newly prescribed antidepressant with a trial of 12 weeks (T5a) or 6 months (T5b)* |

| T6 | Percentage of PTSD patients newly prescribed an SSRI/SNRI with follow-up visit within 30 days | Percentage of depression patients newly prescribed an antidepressant with follow-up visit within 30 days |

| T7 | Percentage of PTSD patients who receive evidence-based psychotherapy for PTSD | Percentage of depression patients who receive evidence-based psychotherapy for depression |

| T8 | Percentage of PTSD patients with a new treatment episode who received any psychotherapy within the first 4 months | Percentage of depression patients with a new treatment episode who received any psychotherapy within the first 4 months |

| T9 | Percentage of PTSD patients with a new treatment episode with 4 psychotherapy visits or 2 evaluation and management visits in the first 8 weeks | Percentage of depression patients with a new treatment episode with 4 psychotherapy visits or 2 evaluation and management visits in the first 8 weeks |

| T10 | Percentage of PTSD patients (PCL score > 43) with response to treatment (5-point reduction in PCL score) at 6 months | Percentage of depression patients (PHQ-9 score > 9) with response to treatment (50% reduction in PHQ-9 score) at 6 months* |

| T12 | Percentage of PTSD patients (PCL score > 43) in PTSD-symptom remission (PCL score < 28) at 6 months | Percentage of depression patients (PHQ-9 score > 9) in depression-symptom remission (PHQ-9 score < 5) at 6 months* |

| T14 | Percentage of PTSD patients with a new treatment episode with improvement in functional status at 6 months | Percentage of depression patients with a new treatment episode with improvement in functional status at 6 months |

| T15 | Percentage of psychiatric inpatient hospital discharges of patients with PTSD with follow-up in 7 days (T15a) or 30 days (T15b)* | Percentage of psychiatric inpatient hospital discharges of patients with depression with follow-up in 7 days (T15a) or 30 days (T15b)* |

NOTE: PCL = PTSD Checklist; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire, 9-item; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SNRI = serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

National Quality Forum (NQF)-endorsed measure.

Methods and Data Sources

We used three types of data for our analyses: administrative, medical record, and symptom questionnaire.

Administrative Data

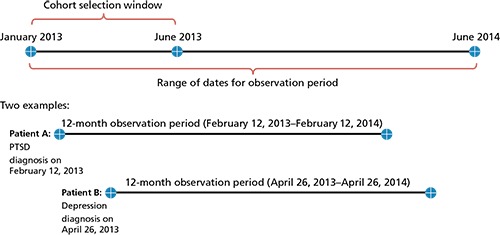

We used administrative data that contained records on all inpatient and outpatient health care encounters for MHS beneficiaries in an MTF (i.e., direct care) or by civilian providers paid for by TRICARE (i.e., purchased care). To describe and evaluate care for PTSD and depression, we identified a cohort of patients who received care for PTSD and a cohort who received care for depression. Service members were eligible for the PTSD or depression cohort if they had at least one outpatient visit or inpatient stay with a primary or secondary diagnosis for PTSD or depression, respectively, during the first six months of 2013 (January 1–June 30, 2013) in either direct care or purchased care (Figure 1). The 12-month observation period starts with the date of the qualifying visit (first visit for PTSD or depression in the cohort selection window) and occurs between January 1, 2013, and June 30, 2014, but the exact start and end dates differ by patient.

Figure 1.

Timing of Cohort Entry and Computation of 12-Month Observation Period

The criteria for selecting these diagnostic cohorts were the following:

Active-Component Service Members—The patient must have been an active-component service member during the entire 12-month observation period.

Received Care for PTSD or Depression—Service members could enter the PTSD or depression cohort if they had at least one outpatient visit or inpatient stay (direct or purchased care) with a PTSD or depression diagnosis (primary or secondary) during January through June 2013. We did not limit the depression cohort to MDD, but rather included other depression diagnoses as well to include codes used to identify depression for denominators for NQF-endorsed measures.1 Also, while the recently updated VA/DoD MDD guideline notes that it does not address non-MDD depression, it recommends that its principles be strongly considered when treating other depressive disorders (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense, 2016).

Engaged with and Eligible for MHS Care—Service members were eligible for a cohort if they had received a minimum of one inpatient stay or two outpatient visits for any diagnosis (i.e., related or not related to PTSD or depression) within the MHS (either direct or purchased care) during the 12-month observation period following the index visit. In addition, service members must have been eligible for TRICARE benefits during the entire 12-month observation period. Members who deployed or separated from the service during the 12-month period were excluded.

Using these criteria, we identified 14,654 service members for the PTSD cohort and 30,496 for the depression cohort. A total of 6,322 service members were in both cohorts, representing 43.1 percent of the PTSD cohort and 20.7 percent of the depression cohort. Therefore, the two cohorts together represent a total of 38,828 unique service members.

To describe the quality of care for PTSD and depression delivered by the MHS, we computed scores for each quality measure. For measures based on administrative data, we also examined variations in quality measure scores by service branch (Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, Navy) and TRICARE region (North, South, West, Overseas). In addition, we examined variations across service member characteristics, including age, race/ethnicity, gender, pay grade, and history of deployment at time of cohort entry.

Administrative data are particularly well suited for assessing care provision and quality across a large population, although such data do have limitations. For example, they do not include clinical detail documented in chart notes, including whether a patient refused a particular treatment or whether an evidence-based psychotherapy was delivered.

Medical Record Data

Medical record review (MRR) was conducted on a stratified, random sample of service members from the PTSD and depression cohorts, limiting the sample to service members who received only direct care during the observation period. This limitation was based on the fact that medical records documenting purchased care were not accessible for abstraction. The source of medical record data was AHLTA, the electronic health record used by the MTFs to document outpatient care. Medical record review incorporated a hybrid methodology where administrative data were used to identify service members within the MRR sample with characteristics relevant to quality measure eligibility.

To select the MRR sample, the study population was restricted to the 16,173 service members in the Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy2,3 who received only direct care during their observation year. For purposes of yielding two distinct MRR samples for PTSD and depression, we randomly assigned each of the 1,616 service members with both PTSD and depression diagnoses to either the PTSD or depression cohort.4 From each of these groups, we drew a random sample of 400 service members. Service members with a new treatment episode (NTE) on the first day of cohort entry were oversampled to ensure the sample contained a sufficient number of service members eligible for the MRR measures focusing on NTEs.5 The sample was also stratified to ensure that service members were represented by branch, region, and by having both PTSD and depression versus having one of these conditions. Sampling weights for estimating the measure scores of the NTE and all-cohort quality measures were applied to account for the stratified sampling plan.

Medical record data provide a level of clinical detail not available from other data sources. However, the comprehensiveness of medical record data depends on the providers' documenting all care that was provided. Data collection from the medical record is also time-intensive and expensive compared to collection of other types of data. In this project, time and budget constraints led to a reduction in the planned medical record data collection and, therefore, a reduction in the number of quality measures that could be computed from this data source. The “dropped” measures were computed using symptom questionnaire data instead (as described next).

Symptom Questionnaire Data

Data from symptom questionnaires are available from a dedicated data collection system within MHS. The system, known as the Behavioral Health Data Portal (BHDP), has been in operation since September 2013 in all of Army's behavioral health clinics, and implementation in other service branches is under way. The BHDP is an easy-to-use and secure web-based system for collecting behavioral health symptom data directly from patients (Hoge et al., 2015) but is separate from the electronic health record where the scores must be entered manually. Our analyses focused on PTSD and depression symptom questionnaires—the PTSD Checklist (PCL) for PTSD, and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression. Each PCL or PHQ-9 score and the date completed were linked to the administrative data records of individuals in the PTSD and depression cohorts. These symptom scores were used to compute scores for selected quality measures and for descriptive and multivariate analyses. These analyses were restricted to subgroups with access to the BHDP (e.g., Army, direct care only, behavioral health encounters). When considered together, these factors mean that the symptom questionnaire data represent only a subset of the service members with PTSD or depression, which may not be representative of all service members with PTSD or depression.

The symptom questionnaire data collected through the BHDP offer a way to track clinical outcomes of treatment for PH conditions delivered by providers at MTFs. Symptom data are captured in structured fields, making the data easily accessible. Despite these advantages, the data have limitations: BHDP is not directly linked to AHLTA, and the provider must therefore either enter the proper diagnosis for the system to know which symptom questionnaire should be administered and how often or change how often the questionnaire should be administered directly; at the time of this study, symptom questionnaires were completed within the BHDP only by patients seen in behavioral health specialty care at an MTF (i.e., direct care). In addition, an unbiased comparison of outcome measures, including symptom scores, across groups should be adjusted for differences in severity, so one group does not appear to have worse outcomes simply because that group's patients have greater pre-existing severity. Furthermore, symptom scores of subgroups of service members (e.g., those with initial and six-month follow-up scores within the observation period) may not be representative of all service members with PTSD or depression, or of all with a symptom score. Note that the symptom questionnaire data were used in two separate analyses, as the basis for computing quality measure scores and in regression analyses.

Characteristics of Service Members Diagnosed with PTSD and Depression, Their Care Settings, and Services Received

Demographic Characteristics

The majority of service members in the PTSD cohort were white, non-Hispanic, male, with nearly half the cohort between 25 and 34 years of age. About a third of the PTSD cohort resided in TRICARE South, with another third located in TRICARE West and one-fifth in TRICARE North. The depression cohort exhibited similar characteristics, except a higher percentage of the depression cohort was female, younger, and never married.

Army soldiers represented 69 and 56 percent of the PTSD and depression cohorts, respectively. Enlisted service members represented nearly 90 percent of both cohorts. Approximately 50 percent (PTSD) and 60 percent (depression) of service members in the cohorts had ten or fewer years of service. In the PTSD cohort, almost 90 percent of service members had at least one deployment at the time of cohort entry, while in the depression cohort, 68 percent had been deployed.

Care Settings and Diagnoses

Patients in the PTSD and depression cohorts received much of their care at MTFs (over 90 percent had at least some direct care); yet 30 percent of patients in the PTSD cohort and 22 percent in the depression cohort received at least some purchased care. Nearly 60 percent of all primary diagnoses coded for encounters (and presumed to be the primary reason for the encounter) in both direct care and purchased care were for non-PH diagnoses. The most common co-occurring PH conditions in both cohorts were adjustment and anxiety disorders, as well as sleep disorders or symptoms. More than half of the PTSD cohort had co-occurring depression at any point during the 12-month observation period.6

Approximately two-thirds of patients in the depression cohort and three-fourths of patients in the PTSD cohort received care associated with a cohort diagnosis (coded in any position, primary or secondary) from MTF mental health specialty settings, while almost half of each cohort had cohort-related diagnoses documented at MTF primary care clinics. Further, patients saw many provider types for care associated with a cohort diagnosis (primary or secondary). About half of patients in both the PTSD and depression cohorts saw primary care providers, and high percentages saw psychiatrists (47 percent for PTSD; 40 percent for depression), clinical psychologists (46 percent for PTSD; 33 percent for depression), and social workers (47 percent for PTSD; 34 percent for depression) for this care. The median number of unique providers seen by cohort patients during the observation year at encounters with a cohort diagnosis (coded in any position) was three for PTSD and two for depression. When considering all outpatient encounters (for any reason), the median number of unique providers was 14 for those in the PTSD cohort and 12 for those in the depression cohort. This suggests that patients with PTSD or depression may be seen by multiple providers across primary and specialty care, highlighting the importance of understanding these patterns to inform efforts to improve coordination of care for these patients.

Assessment and Treatment Characteristics

Approximately 20 percent of each cohort had an inpatient hospitalization for any reason (i.e., medical or psychiatric), but a substantial proportion of these inpatient stays had the cohort condition listed as a primary or secondary diagnosis (66 percent for PTSD; 60 percent for depression). For inpatient hospitalizations that had a primary diagnosis of PTSD or depression, the median length of stay per admission was 25 days for patients in the PTSD cohort and seven days for patients in the depression cohort. Utilization of outpatient care for any reason was high, with medians of 40 and 31 visits for PTSD and depression during the one-year observation period, respectively, a finding possibly related to the large number of unique providers seen. Most of these visits were for conditions unrelated to the cohort diagnosis, with only ten and four of these visits having PTSD and depression as the primary diagnosis, respectively.

Over three-quarters of patients in the PTSD cohort and more than two-thirds of the depression cohort received psychiatric diagnostic evaluation or psychological testing, while other testing and assessment methods, including neuropsychological testing and health and behavior assessment, were used with much lower frequency. A high percentage of patients received at least one psychotherapy visit (individual, group, or family therapy)—approximately 91 percent of the PTSD cohort and 83 percent of the depression cohort. For both cohorts, individual therapy was received by a much higher percentage of patients than group therapy, while family therapy was received by a much smaller percentage. If receiving psychotherapy, patients in the PTSD cohort received an average of 19 psychotherapy sessions (across therapy modalities), while approximately 15 of these visits had a PTSD diagnosis (in any position). Patients in the depression cohort received an average of 14 psychotherapy sessions, of which approximately nine visits had a depression diagnosis (in any position).

More than 85 percent of service members in both cohorts filled at least one prescription for psychotropic medication during the observation year. Antidepressants were filled by the highest percentage of both cohorts (77 and 79 percent of the PTSD and depression cohorts, respectively), while stimulants were filled by the smallest percentage (11 percent in both cohorts). Of note is the finding that about 33 percent of the PTSD cohort and 25 percent of the depression cohort filled at least one benzodiazepine prescription. In addition, 57 and 50 percent of the PTSD and depression cohorts, respectively, filled at least one opioid prescription. Patients in the PTSD and depression cohorts also filled prescriptions for multiple psychotropic medications from different classes or within the same medication class. About 25 and 29 percent of the PTSD and depression cohorts, respectively, had prescriptions from two different classes, while 42 percent of the PTSD cohort and 26 percent of the depression cohort filled prescriptions from three or more classes of medication. These results indicate that many patients in both cohorts received prescriptions for multiple psychotropic medications.

Quality of Care for PTSD and Depression

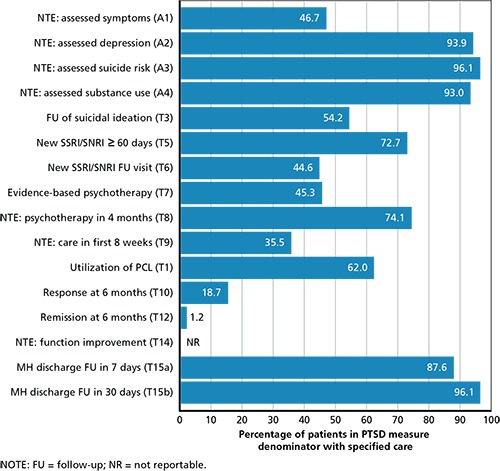

Figures 2 and 3 summarize our overall findings for each quality measure for the PTSD and depression cohorts, respectively. Each quality measure focuses on the subset of patients who met the eligibility requirements as specified in the measure denominator. Measure scores above 75 percent were considered to be high, and those below 50 percent were considered to be low, although published scores for the same or similar measures in comparable populations also informed our assessment. Starting with care for PTSD, approximately 47 percent of active-component service members in the MRR sample with a new treatment episode (NTE) of PTSD had an assessment of symptom severity with the PCL, but 93 to 96 percent had an assessment of depression, suicide risk, or recent substance use (Figure 2). However, 54 percent of PTSD patients in the MRR sample had appropriate follow-up for suicidal ideation. Approximately 73 percent of the PTSD cohort with a new prescription for an SSRI or SNRI filled prescriptions for at least a 60-day supply. Of those who received a new SSRI/SNRI prescription, about 45 percent had a follow-up evaluation and management (E&M) visit within 30 days. Nearly three-quarters of service members in the PTSD cohort with a new treatment episode received some type of psychotherapy within four months. However, less than half (45 percent) of PTSD patients in the MRR sample who had psychotherapy had at least two documented components of evidence-based therapy (EBT). A low proportion (36 percent) received a minimally appropriate level of care for patients entering a new treatment episode, defined as receiving four psychotherapy visits or two E&M visits within the initial eight weeks. Minimal utilization of the PCL for PTSD symptom assessment based on symptom questionnaire data increased from 44 percent in the first four-month interval to 62 percent in the last four-month interval of the observation year. While this increase in rate is encouraging, it is based on symptom questionnaire data limited to the Army and patients seen in behavioral health settings in direct care. Percentages with response to treatment and remission for PTSD in six months were low, at 19 percent and 1 percent, respectively. Again, these percentages with response and remission are to be taken in the context of the data limitations noted above. Improvement in function within six months of a new PTSD or depression diagnosis could not be assessed due to the lack of use in the studied population of standardized tools to evaluate this outcome. Percentages with follow-up after hospitalization for a mental health condition were high: 88 percent within seven days of discharge, and 96 percent within 30 days. For the six PTSD measures based on administrative data scored in 2012–2013, scores in 2013–2014 increased slightly (increase of 1 to 3 percentage points) for five of them.

Figure 2.

PTSD Quality Measure Scores, 2013–2014

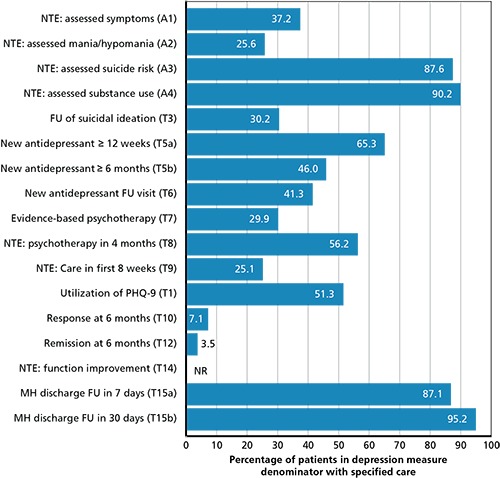

Figure 3.

Depression Quality Measure Scores, 2013–2014

In the depression cohort, 37 percent in the MRR sample beginning a new treatment episode had a baseline assessment of symptom severity with the PHQ-9 (based on the medical record), and 26 percent had an assessment for behaviors of mania or hypomania, but 88 percent and 90 percent had an assessment for suicide risk and recent substance use, respectively, Figure 3). A low proportion (30 percent) of patients with depression and suicidal ideation in the MRR sample had appropriate follow-up. Almost two-thirds of service members with a new prescription for an antidepressant medication in the depression cohort filled at least a 12-week supply, and 46 percent filled at least a six-month supply. Among those who filled a new prescription for an antidepressant, 41 percent had a follow-up E&M visit within 30 days. Over half of service members in the depression cohort (56 percent) received psychotherapy within four months of a new treatment episode of depression. However, a low proportion (30 percent) of patients with depression in the MRR sample who had psychotherapy had at least two documented components of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). A similar low percentage of 25 percent of service members in the depression cohort received a minimum of four psychotherapy visits or two E&M visits within the first eight weeks of their new depression diagnosis. Rates of utilization of the PHQ-9 to assess depression symptoms increased during each measured increment of the 12-month observation period; by the third (and final) four-month period, minimal PHQ-9 utilization had increased from 36 percent in the first four-month interval to 51 percent during the last four-month interval of the observation year. Percentages with response to treatment and remission for depression in six months were low at 7 percent and 4 percent, respectively. These percentages for depression, as with PTSD, were based on symptom questionnaire data limited to the Army and patients seen in behavioral health settings in direct care. Percentages with follow-up after discharge from a hospitalization for a mental health condition for those with depression were high: 87 percent within seven days of discharge, and 95 percent within 30 days. Six of seven depression measures computed using administrative data had scores in 2013–2014 that increased from those in 2012–2013, but these increases were small (i.e., increases ranged from 1 to 4 percentage points).

While it is often difficult, or not appropriate, to directly compare results from other health care systems or studies or related measures, prior published results for these measures (or highly related measures) are presented in this study to provide important context to guide interpretation. These comparisons serve to highlight areas where the MHS may outperform other health care systems (e.g., in timely follow-up after inpatient mental health discharge), perform at a comparable level (e.g., adequate trial of antidepressant therapy for patients with depression with a new prescription) or that may be high priorities for improvement (e.g., receipt of adequate care in the first eight weeks of a new treatment episode). It should be noted that although the MHS should work toward improvement on all of these measures, the results presented provide a preliminary guide for prioritizing targets for routine measurement and improvement. The MHS could select high-priority targets based on those measures with lower scores (e.g., receipt of adequate care in the first eight weeks of a new treatment episode) or measures that assess processes that could be particularly high-risk for service members if not completed (e.g., follow-up after suicide risk).

Variations in Administrative Data Measure Scores

Using 2013–2014 administrative data, we conducted an assessment of the variation in measure scores by service branch, TRICARE region, and service member characteristics, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, pay grade, and deployment history as we had conducted on 2012–2013 administrative data. Most of the variations in measure scores persisted between the two years. The largest differences occurred by branch of service, TRICARE region, pay grade, and age. For branch of service, follow-up within seven days after a mental health hospitalization (T15a) varied by up to 16 percent and 15 percent in the PTSD and depression cohorts, respectively. For TRICARE region, follow-up within 30 days after a new prescription of SSRI/ SNRI (PTSD-T6) varied up to 12 percent in the PTSD cohort. For pay grade, percentages with adequate filled prescriptions for SSRI/SNRI for PTSD (PTSD-T5) and antidepressants for depression (Depression-T5a and -T5b) varied by up to 8, 24, and 30 percent, respectively. For age, percentages with adequate filled prescriptions for SSRI/SNRI for PTSD (PTSD-T5) and antidepressants for depression (Depression-T5a and -T5b) varied by up to 10, 18, and 24 percent, respectively. The depression measure scores suggest even more variation across subgroups than the PTSD measures. In targeting areas for quality improvement activities, differences in measure scores based on service branch, TRICARE region, pay grade, and age should be considered. For example, quality measures with particularly large variations in scores or variations across multiple characteristics could be the first measures selected for ongoing monitoring and quality improvement.

Use of Symptom Questionnaires in MTFs

Since 2012, Army behavioral health clinics have collected self-reported outcome data using standardized symptom questionnaires using the BHDP. Army intends to use these symptom scores to inform both clinical care and assessment of patient outcomes. Of the 8,510 Army personnel in our PTSD cohort who had two or more mental health specialty care visits, 45 percent completed two or more PCLs over their 12-month observation period in 2013–2014. Of the 13,746 Army personnel in the depression cohort who had two or more mental health specialty care visits, one-third completed two or more PHQ-9s in their 12-month observation period in 2013–2014.

We assessed the use of the BHDP for completing the PCL and PHQ-9 on a monthly basis from February 2013 through June 2014. We found the overall PCL completion rate in the PTSD cohort and overall PHQ-9 completion rate in the depression cohort increased steadily in 2013–2014 to 21.5 and 17.2 per 100 MH specialty visits, respectively, in June 2014. Although these rates are relatively low, they represent a time period early in the use of the BHDP system when providers and patients were new to the system, and completion rates would be expected to continue to increase over time. Notably, the completion rate was consistently higher for the PCL by the PTSD cohort than for the PHQ-9 for the depression cohort throughout the entire period.

Symptom Scores: Change over Time and Link to Process Measures

In examining changes in symptom scores over time, we found in the PTSD and depression cohorts that symptom scores improved from the initial score to six months later among Army soldiers with two or more mental health specialty visits by a statistically significant, but not a clinically meaningful, amount. Reductions in symptom scores were larger for the subset of Army soldiers in a new treatment episode and/or with initial PCL scores greater than or equal to 50 points or initial PHQ-9 scores greater than or equal to 10 points. We did not detect significant associations between receiving recommended care, as specified in the PTSD and depression quality measures, and improvements in patient symptoms at six months after the initial score. A limitation of these analyses is that the data reflect the subset with continued engagement and reassessment in behavioral health specialty care. For example, patients with multiple behavioral health specialty care visits may improve and complete treatment in less than five months. This subgroup would not be reflected in these results because its members would not be in treatment to be assessed at the six-month point in time. However, similar results were found for examining symptom score change from the initial score to three months later. Though we weight our analysis to account for differences between those with versus without reassessments, the weights adjust only for observed characteristics at the time of the initial score. Finally, while these analyses are preliminary, they demonstrate the potential value of routinely collected data on patient outcomes. More research on particular subgroups may demonstrate clinically meaningful improvement within six months (e.g., service members with more severe symptoms at the time of the initial score).

Policy Implications

PTSD and depression are frequent diagnoses in active-duty service members (Blakeley and Jansen, 2013). If not appropriately identified and treated, these conditions may cause morbidity that would represent a potentially significant threat to the readiness of the force. Assessments of the current quality of care for PTSD and depression in the MHS are an important step toward future efforts to improve care. Based on our findings, we offer several recommendations related to measuring, monitoring, and improving the quality of care received by patients with PTSD or depression in the MHS. These are high-level recommendations that would be implemented most efficiently in an enterprise-wide manner.

Recommendation 1. Improve the Quality of Care Delivered by the Military Health System for Psychological Health Conditions by Immediately Focusing on Specific Care Processes Identified for Improvement

The results presented in this study, combined with the results presented in the Phase I study (Hepner et al., 2016), represent perhaps the largest assessments of quality of outpatient care for PTSD and depression for service members ever conducted. We concluded that while there are some strengths, quality of care for psychological health conditions delivered by the MHS should be improved. For both PTSD and depression, we observed low percentages (36 percent and 25 percent, respectively) of adequate initial care in the first eight weeks following an initial diagnosis (either four psychotherapy or two medication management visits) and of receiving a medication management visit within 30 days of starting a new medication (45 percent and 41 percent, respectively). This suggests that the MHS should identify procedures that would ensure service members receive an adequate intensity of treatment and follow-up when beginning treatment. Further, we found the MHS had high percentages for screening for suicide risk. However, providing adequate follow-up for those with suicide risk could be improved given that a low proportion (30 percent) of service members with depression who were identified as having suicide risk in a new treatment episode received adequate follow-up (i.e., assessment for plan and access to lethal means, referral or follow-up appointment, and discussion of limitation of access to lethal means if access assessment was positive or was not done). Appropriate follow-up care for suicide risk is an essential component of reducing the rate of suicide among service members. Finally, given the extensive and complex patterns of psychopharmacologic prescribing, further analysis of these patterns and development and implementation of quality monitoring and improvement strategies should be a high priority.

Recommendation 2. Expand Efforts to Routinely Assess Quality of Psychological Health Care

Recommendation 2a. Establish an Enterprise-Wide Performance Measurement, Monitoring, and Improvement System That Includes High-Priority Standardized Measures to Assess Care for Psychological Health Conditions

Currently, there is no coordinated enterprise-wide (direct and purchased care) system for monitoring the quality of PH care. A separate system for PH is not required; high-priority PH measures could be integrated into an enterprise-wide system that assesses care across medical and psychiatric conditions. The review of the MHS (U.S. Department of Defense, 2014) highlighted the need for such a system as well. Although the quality measures presented in this study highlight areas for improvement, quality measures for other PH conditions should be considered for reporting (e.g., care for alcohol use disorders). Furthermore, an infrastructure is necessary to support the implementation of quality measures for PH conditions on a local and enterprise-wide basis, and to support other activities, including monitoring performance, conducting analysis of measure scores, validating the process-outcome link for each measure, and evaluating the effect of quality improvement strategies. This function could be executed by a DoD center focused on psychological health (e.g., DCoE) or additional psychological health quality measures could be integrated into ongoing efforts conducted by DoD Health Affairs.

Recommendation 2b. Routinely Report Quality Measure Scores for PH Conditions Internally, Enterprise-Wide, and Publicly to Support and Incentivize Ongoing Quality Improvement and Facilitate Transparency

Routine internal reporting of quality measure results (MHS-wide and at the service and MTF level) provides valuable information to identify gaps in quality, target quality improvement efforts, and evaluate the results of those efforts. The MHS is implementing quality improvement strategies using an “enterprise management approach” and “defining value from the perspective of the patient,” including use of systems-approach interventions such as case managers to coordinate care (Woodson, 2016). Analyses of variations in care across service branches, TRICARE regions, or patient characteristics can also guide quality improvement efforts. While Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and civilian health care settings have used monetary incentives for administrators and providers to improve performance, the MHS could provide special recognition in place of financial incentives or provide additional discretionary budget to MTFs for improved performance or maintaining high performance. In addition, reporting of selected quality measures for PH conditions could be required under contracts with purchased care providers (Institute of Medicine, 2010). Quality measures are an essential component of alternative payment models, such as value-based purchasing.

Reporting quality measure results externally provides transparency, which encourages accountability for high-quality care. External reporting could be focused on a more limited set of quality measures that are most tightly linked with outcomes or reported by other health care systems, while a broader set of measures that are descriptive or exploratory could be reported internally. In addition, external reporting allows comparisons with other health care systems that report publicly (though appropriate risk-adjustment is required for outcome measures). Finally, external reporting allows the MHS to demonstrate improvements in performance over time to multiple stakeholders, including service members and other MHS beneficiaries, providers, and policymakers.

In 2016, the MHS and the Defense Health Agency (DHA) launched a public, online quality reporting system (http://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Access-Cost-Quality-and-Safety) with measure scores by MTF for measures of patient safety, health care outcomes, quality of care, and patient satisfaction and access to care (Military Health System and Defense Health Agency, 2016). The set of HEDIS outpatient measures displayed on the site includes one PH measure: follow-up within seven days and 30 days after mental health discharge. The set of ORYX inpatient measures displayed on the site includes two PH measures: substance use and tobacco treatment.7 This system could be expanded to include other PH measures and coordinated enterprise-wide for monitoring the quality of all direct and purchased care. These are promising efforts that the MHS should continue to expand.

Recommendation 3. Expand Efforts to Monitor and Use Treatment Outcomes for Service Members with Psychological Health Conditions

Recommendation 3a. Integrate Routine Outcome Monitoring for Service Members with PH Conditions as Structured Data in the Medical Record as Part of a Measurement-Based Care Strategy

Routine symptom monitoring for PTSD, depression, and anxiety disorders is now mandated by policy across the MHS (U.S. Department of Defense, 2013) using the BHDP (U.S. Department of Defense, 2016; U.S. Department of Defense and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2014; Department of the Army Headquarters, undated), and the service branches are working toward full implementation of this policy. While encouraging routine symptom monitoring is a positive step, the chief limitation of the BHDP is that it is not electronically linked to the medical record. Because of this, the symptom scores from the BHDP must be entered manually into the medical record by the clinician. As the new medical record system for the MHS is being developed, it would be advantageous to integrate outcome tracking within the medical record. While there are structured, data-mineable fields for symptom questionnaire data currently in AHLTA, this approach does not easily support tracking of patient progress over time—a capability currently included in the BHDP. Further, the MHS should explore how to obtain similar data for patients seen in purchased care.

Recommendation 3b. Monitor Implementation of BHDP Across Services and Evaluate How Providers Use Symptom Data to Inform Clinical Care

We demonstrated the increasing use of the PCL and the PHQ-9 over time during 2013–2014 among Army soldiers with PTSD or depression seen in MTF behavioral health clinics, but also highlighted that the Army can continue to increase the rates of routinely using these measures with patients. Other service branches are now migrating to BHDP. Assessing use of BHDP across all service branches will be important to ensure full implementation occurs. Further, it is important to understand how providers are making decisions in using the BHDP and ensure providers are able to integrate symptom questionnaire information into treatment planning and adjustment, rather than simply entering data because the MHS requires it.

Recommendation 3c. Build Strategies to Effectively Use Outcome Data and Address the Limitations of These Data

The Army's use of BHDP likely represents one of the largest efforts to capture outcomes for patients with PH conditions in the United States, an effort that we highly commend. Results from the outcome quality measures provide a baseline assessment for Army MTF behavioral health clinics and suggest that efforts to monitor and improve treatment outcomes are needed. Our analyses highlighted some of the challenges of using clinic-based assessments of outcomes. A chief limitation of the BHDP is that outcome data are not collected if patients do not return to MTF specialty behavioral health care. Of those with an initial PCL score, 32.6 percent (1,762/5,405) had a PCL score five to seven months later. Of those with an initial PHQ-9 score, 27.6 percent (2,009/7,273) had a PHQ-9 score five to seven months later. Telephone follow-up of patients who did not return to treatment at six months would provide important data about their clinical status at that point in time. Alternatively, this could be integrated into ongoing efforts to assess patient experiences in receiving care, including patient satisfaction, timeliness of care, and interpersonal quality (e.g., felt respected). Further, the BHDP typically captures patients seen in specialty behavioral health care at an MTF and does not include patients who receive their care in primary care clinics (which frequently occurs, particularly for depression) or those who use purchased care for some or all of their care. While AHLTA includes structured, data-mineable fields to capture symptom questionnaire data, AHLTA does not easily support monitoring patient progress over time. Finding ways to collect outcome data routinely across all patients receiving care for psychological health conditions would bolster the representativeness of the data and offer a more complete picture of quality.

Recommendation 4. Investigate the Reasons for Significant Variation in Quality of Care for PH Conditions by Service Branch, Region, and Service Member Characteristics

The 2013–2014 quality measure scores in the current study varied by member and service characteristics in the same ways as our previous 2012–2013 results (Hepner et al., 2016). We found several statistically significant differences in measure scores by service branch, TRICARE region, and service member characteristics, many of which may represent clinically meaningful differences. Understanding and minimizing variations in care by personal characteristic (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, and geographic region) is important to ensure that care is equitable, one of the six aims of quality of care improvement in the seminal report Crossing the Quality Chasm (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Exploring the structure and processes used by MTFs and staff in high- and low-performing service branches and TRICARE regions may help to identify promising improvement strategies for, and problematic barriers to, providing high-quality care and moving toward the goal of being a high-reliability organization (Woodson, 2016). However, the first step to understanding how to minimize variations and improve quality is to ensure systems are in place to routinely obtain results on high-priority measures.

Summary

This study expands previous RAND research assessing the quality of care provided to active-component service members with PTSD or depression in the MHS. In this study, we analyzed three types of data (administrative, medical record, and symptom questionnaire) to assess performance using 30 quality measures (33 measures, when accounting for scores reported separately within a measure). We also used administrative data to describe patterns of care received by service members with PTSD or depression and examine variations in quality measure scores. Finally, we analyzed symptom questionnaire data to evaluate the relationship between quality of care and patient outcomes. MHS-wide performance across the quality measures was mixed. The MHS demonstrated excellent care in some areas; six measure scores (four for PTSD; two for depression) were at or above 90 percent (assessing PTSD symptom severity and PTSD and depression comorbidity and follow-up after MH hospitalization). In contrast, six PTSD measure scores and nine depression measure scores indicated that fewer than 50 percent of service members received the recommended care. In general, MHS-wide measure scores for PTSD were higher than those for depression. Analyzing variations in administrative data quality measure scores revealed several significant differences, with the largest variations in performance by service branch, TRICARE region, pay grade, and age. These variations are important because they suggest that care is not consistently of high quality for all service members. No significant associations were found between receiving recommended care and improvements in patient symptom scores at six months, but the analyses were limited to a subgroup of patients with continued engagement and reassessment in behavioral health specialty care and a select group of quality measures. These findings highlight areas in which the MHS delivers excellent care, as well as areas that should be targeted for quality improvement.

Notes

ICD-9 codes for depression: 296.20–296.26, 296.30–296.36, 293.83, 296.90, 296.99, 298.0, 300.4, 309.1, and 311.

Coast Guard service members were not sampled since their relatively small proportion in the service member population would not allow for a sufficient number of them to be sampled to yield Coast Guard–specific estimates.

Those with missing region are excluded from the sampled population.

The probability of random assignment to the PTSD cohort is higher (0.70 versus 0.30), since the proportion of the cohort with both PTSD and depression at the time of cohort entry is higher for the PTSD (32 percent) than for the depression cohort (12 percent).

NTEs were limited to those that occurred on Day 1 of cohort entry (representing 96 and 97 percent of the total NTEs for PTSD and depression, respectively) to maximize the length of the observation period. Those with NTEs occurring only after Day 1 of cohort entry (e.g., a patient could have entered the cohort in ongoing treatment and then had a three-month clean period with no treatment, followed by receiving treatment again) were not sampled.

Co-occurring diagnoses examined over the entire 12-month observation period; overlap between the two cohorts was based on diagnoses at cohort entry, limited to the first six months of 2013. Therefore, the prevalence of comorbid PTSD/depression may be higher than the overlap between the two cohorts.

The ORYX quality measures (also known as the National Hospital Quality Measures) were developed by the Joint Commission for care in the inpatient setting (Joint Commission, 2017). ORYX is not an acronym.

This research was sponsored by the Department of Defense's Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury (DCoE) and conducted within the Forces and Resources Policy Center of the RAND National Defense Research Institute, a federally funded research and development center sponsored by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Staff, the Unified Combatant Commands, the Navy, the Marine Corps, the defense agencies, and the defense Intelligence Community.

References

- Department of the Army Headquarters. “Behavioral Health Data Portal,”. http://armymedicine.mil/Pages/BHDP.aspx Army Medical Command, undated. As of December 16, 2015.

- Hepner Kimberly A., Roth Carol P., Farris Coreen, Sloss Elizabeth M., Martsolf Grant, Pincus Harold A., Watkins Katherine E., Epley Caroline, Mandel Daniel, Hosek Susan. and Farmer Carrie M. Measuring the Quality of Care for Psychological Health Conditions in the Military Health System: Candidate Measures for PTSD and Major Depression. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2015. http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR464.html RR-464-OSD. As of February 18, 2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepner Kimberly A., Sloss Elizabeth M., Roth Carol P., Krull Heather, Paddock Susan M., Moen Shaela, Timmer Martha J. and Pincus Harold A. Quality of Care for PTSD and Depression in the Military Health System: Phase 1 Report. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2016. http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR978.html RR-978-OSD. As of February 18, 2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge Charles W., Ivany Christopher G., Brusher Edward A., Brown Millard D., 3rd, Shero John C., Adler Amy B., Warner Christopher H. and Orman David T. “Transformation of Mental Health Care for U.S. Soldiers and Families During the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars: Where Science and Politics Intersect,”. American Journal of Psychiatry. pp. 334–343. November 10, 2015, pp. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Provision of Mental Health Counseling Services Under TRICARE. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Military Health System and Defense Health Agency. “Quality, Patient Safety and Access Information for MHS Patients,”. 2016. http://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Access-Cost-Quality-and-Safety/Patient-Portal-for-MHS-Quality-Patient-Safety-and-Access-Information Falls Church, Va. As of July 20, 2016.

- National Quality Forum. “Patient Safety,”. http://www.qualityforum.org/Topics/Patient_Safety.aspx web page, 2017a. As of February 15, 2017.

- National Quality Forum. “Disparities,”. http://www.qualityforum.org/Topics/Disparities.aspx web page, 2017b. As of February 15, 2017.

- U.S. Department of Defense. Military Treatment Facility Mental Health Clinical Outcomes Guidance Memorandum. 2013. http://www.dcoe.mil/Libraries/Documents/MentalHealthClinicalOutcomesGuidance_Woodson.pdf Washington, D.C., Assistant Secretary of Defense, Affairs, Manpower and Reserve. As of August 18, 2015.

- U.S. Department of Defense. “Military Health System Review: Final Report to the Secretary of Defense,”. 2014. http://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Access-Cost-Quality-and-Safety/MHS-Review Military Health System official website, Defense Health Agency, Falls Church, Va. As of August 18, 2015.

- U.S. Department of Defense. Section 729 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (Public Law 114-92), Plan for Development of Procedures to Measure Data on Mental Health Care Provided by the Department of Defense. Report to Armed Services Committees of the Senate and House of Representatives. September 2016.

- U.S. Department of Defense and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. “DoD and VA Take New Steps to Support the Mental Health Needs of Service Members and Veterans,”. http://www.defense.gov/News/News-Releases/News-Release-View/Article/605153/dod-and-va-take-new-steps-to-support-the-mental-health-needs-of-service-members press release No. NR-446-14, August 26, 2014. As of March 15, 2015.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense. “VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline: for Management of Major Depressive Disorder,”. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/mdd/MDD_FULL_3c1.pdf Version 2.0–2008, Management of MDD Working Group, May 2009. As of September 10, 2013.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense. “VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,”. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/PTSD-full-2010c.pdf Version 2.0–2010, Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Working Group, October 2010. As of September 10, 2013.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense. Mangement of Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/mh/mdd/index.asp “VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Major Depressive Disorder,” Version 3.0–2016. April 2016. As of May 27, 2016.

- Woodson Jonathan. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. 2016. “The Military Health System as a High Reliability Organization,” memo to military health system leadership.