Abstract

Background

The mental health impact of the 2014–2016 Ebola epidemic has been described among survivors, family members and healthcare workers, but little is known about its impact on the general population of affected countries. We assessed symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the general population in Sierra Leone after over a year of outbreak response.

Methods

We administered a cross-sectional survey in July 2015 to a national sample of 3564 consenting participants selected through multistaged cluster sampling. Symptoms of anxiety and depression were measured by Patient Health Questionnaire-4. PTSD symptoms were measured by six items from the Impact of Events Scale-revised. Relationships among Ebola experience, perceived Ebola threat and mental health symptoms were examined through binary logistic regression.

Results

Prevalence of any anxiety-depression symptom was 48% (95% CI 46.8% to 50.0%), and of any PTSD symptom 76% (95% CI 75.0% to 77.8%). In addition, 6% (95% CI 5.4% to 7.0%) met the clinical cut-off for anxiety-depression, 27% (95% CI 25.8% to 28.8%) met levels of clinical concern for PTSD and 16% (95% CI 14.7% to 17.1%) met levels of probable PTSD diagnosis. Factors associated with higher reporting of any symptoms in bivariate analysis included region of residence, experiences with Ebola and perceived Ebola threat. Knowing someone quarantined for Ebola was independently associated with anxiety-depression (adjusted OR (AOR) 2.3, 95% CI 1.7 to 2.9) and PTSD (AOR 2.095% CI 1.5 to 2.8) symptoms. Perceiving Ebola as a threat was independently associated with anxiety-depression (AOR 1.69 95% CI 1.44 to 1.98) and PTSD (AOR 1.86 95% CI 1.56 to 2.21) symptoms.

Conclusion

Symptoms of PTSD and anxiety-depression were common after one year of Ebola response; psychosocial support may be needed for people with Ebola-related experiences. Preventing, detecting, and responding to mental health conditions should be an important component of global health security efforts.

Keywords: health systems, public health, viral haemorrhagic fevers, kap survey

Key messages.

What is already known about this topic?

Past studies have documented the mental health impact of other infectious disease outbreaks including after the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic and 2009 H1N1 pandemic.

Some prior studies have examined the effects of Ebola on directly affected populations such as healthcare workers who cared for patients with Ebola.

There is limited documentation, however, of the mental health impact of the Ebola epidemic at the population level.

What are the new findings?

To the best of our knowledge, the assessment was the first national survey that examined the impact of the devastating Ebola epidemic on population-level mental health using globally validated scales, and conducted after more than a year of ongoing transmission of Ebola in the country.

We found that symptoms of PTSD and anxiety-depression were common after one year of the outbreak, especially among those with Ebola-related experiences.

Furthermore, we have demonstrated the ability to rapidly administer brief mental health screeners at the population level to identify factors associated with mental health symptomology towards the end of an unprecedented infectious disease epidemic.

Recommendations for policy

Preventing, detecting and responding to mental health conditions should be an important component of global health security efforts.

Use of brief mental health screeners during outbreak response could increase the ability to identify and address the needs of at-risk groups.

So doing could help avert the substantial short-term and long-term effects of mental health disorders on individual health and on national health systems, societies and economies.

Introduction

More than 11 300 deaths were attributed to the largest recorded outbreak of Ebola virus disease (Ebola) between 2014 and 2016, primarily in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea.1 In Sierra Leone alone, there were reports of more than 14 100 Ebola cases, resulting in over 3900 deaths, and more than 30 000 individuals were quarantined due to possible Ebola exposure.2 Little is known about the epidemic’s effects on the mental health of the general population in the affected countries.

Numerous studies have examined the mental health effects associated with other infectious disease outbreaks including the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic3–12 and 2009 novel influenza A (H1N1) pandemic.13–22 The mental health impact of other emergencies, such as bioterrorism, have also been documented among survivors.23 Psychological distress, anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been recorded among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement24 including those affected by the civil conflict in Sierra Leone between 1992 and 2002.25 26

Known risk factors for anxiety, depression and PTSD—including experience with ill individuals, perceptions of threat, high levels of mortality, food and resource insecurity, stigma and discrimination, and intolerance of uncertainty—may have been experienced by people in Sierra Leone during the Ebola epidemic. Adverse mental health outcomes could be expected in the general population given the magnitude of the epidemic.15 27 High levels of distress have been documented among Ebola survivors in Guinea and Sierra Leone28 29 and healthcare workers (HCWs) in all three affected countries.29 30

There are few mental health resources in Sierra Leone; for example, when the Ebola outbreak began, there was only one trained psychiatrist for the population of over 7 million. Assessments of mental health and of risk factors for mental illness can support policy efforts to improve resources to address mental health and inform how resources can be targeted most efficiently—especially in the aftermath of a devastating Ebola epidemic.

The Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention collaborated with FOCUS 1000 and other stakeholders to implement a national, household-based Ebola Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAP) Survey in July 2015. The survey assessed respondents’ Ebola-related KAP, perceptions of ongoing Ebola threat, Ebola-related experiences, and anxiety-depression and PTSD symptoms. The present analysis aimed to estimate prevalence of mental health symptoms and factors associated with having symptoms in the general population.

Methods

Sampling

The national survey employed a multistage cluster sampling procedure with primary sampling units selected with probability relative to their size. In order to attain 95% confidence levels and CIs of ±3% estimates of the national population, 3640 individuals were approached across the 4 regions and 14 districts of Sierra Leone. Using Sierra Leone’s most recent census list (2004) of enumeration areas as the sampling frame, 91 enumeration areas were randomly selected across all 14 districts. Within each cluster, 20 households were selected using systematic random sampling. To generate reliable district-level estimates for key districts, we oversampled in the three districts still experiencing active Ebola transmission. A weighting factor was applied to each record to adjust for the different sample sizes taken in different districts. Within each household, the household head and another individual (aged between 15 years and 24 years) or a woman were approached for consent and interviewed.

Main outcomes and measures

Survey questions included sociodemographic characteristics, Ebola experience, perceived Ebola threat, anxiety-depression symptomology and PTSD symptomology (Supplementary file 1). Ebola experience variables included whether participants knew someone who had died from Ebola and whether they knew someone who had been quarantined due to Ebola exposure. Participants whose only reported experience with Ebola-related death (1.4%, n=50) or quarantine was related to public figures (1.5% of sample, n=55), such as well-known medical doctors who died from Ebola, were excluded from this analysis. These two variables were also combined into a two-level composite item which included: (1) no experience with Ebola-related death or quarantine; (2) knowing others who had been quarantined or had died from Ebola.

Participants’ perceptions of Ebola as a threat were measured by four items that asked whether they perceived that Ebola was no longer a threat to (1) Sierra Leone; (2) their district; (3) their community; and (4) their household. Participants responded using 4-point Likert Scale items ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). Responses were further dichotomised into ‘agree’ and ‘disagree,’ and the scores reversed so that higher scores represented more perceived risk. We also created a composite score across all four domains with 1 representing ‘any perceived Ebola threat’ and 0 representing ‘no perceived Ebola threat.’

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were measured by Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4).31 PHQ-4 was developed by combining two ultrabrief screeners, the PHQ-2 and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale, that have been demonstrated to reliably measure depression and anxiety symptoms. Participants were asked to report their symptoms of depression and anxiety in the past 2 weeks on a Likert Scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) for a maximum score of 12. The sample was further dichotomised into those who expressed any symptoms compared with those who did not by creating a new composite variable. We also examined the prevalence of anxiety and depression using the established clinical cut-off total score of 6, which represents the proportion of people who would be considered as having clinical levels of depression or anxiety if the screener were used for diagnostic purposes.32

Symptoms of PTSD were measured by the Impact of Event Scale-6 (IES-6),33 which is a validated, shortened version of the full IES-revised (IES-r).34 35 The full scale contains 22 items (scored from 0 to 88) with demonstrated reliability and validity to measure PTSD symptoms across different cultures and settings. While IES-r is generally not used to diagnose PTSD in clinical settings, it is widely used for screening at-risk patients with PTSD. The IES-6 includes a total of six items—two items from each of the three subscales of the measure, namely intrusion, hyperarousal and avoidance.33 Participants were asked to report their PTSD symptoms in the past 7 days on a Likert Scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). We dichotomised the sample into those who expressed any symptoms versus those who did not by creating a new composite variable. We evaluated respondents for whom PTSD may be a ‘clinical concern’ using an inputted 1.09 mean item cut-off score (equivalent to 24/88 on IES-r).36 In addition, we assessed respondents who met ‘probable diagnosis’ of PTSD using an inputted 1.5 mean item cut-off score (equivalent to 33/88 total score in IES-r).37

Data collection

In June 2015, FOCUS 1000 recruited 75 experienced data collectors, 25 team supervisors and 4 regional supervisors. They were trained for a week on overall assessment protocols and guidelines, informed consent, safety and security precautions, administration of questionnaire, and quality control and assurance. The training included oral translation of each item into local languages (Krio, Mende, Temne and Limba), back translations (orally), group discussions of the translations for accuracy in meaning, role plays to reflect possible range of responses, and group consensus on the final translations to ensure consistent and accurate use of each item. In July 2015, the trained data collectors used Open Data Kit for digital data collection at the household level. Nearly all interviews (>90%) were conducted in Krio.

In July 2015, when the Ebola KAP was administered, 99% of the cumulative confirmed Ebola cases in the country had been reported.38 Control activities continued, including provision of prevention messages, case detection, contact identification, quarantine and monitoring, and management of cases and deaths. Quarantine involved 21 days of home-based isolation with armed uniformed police dispatched to enforce restriction of movement in and out of the household.39 Quarantined individuals were clinically monitored, and if Ebola was suspected, they were transferred to a holding centre for testing.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using SPSS V.22. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed p-value less than 0.05. For reliability, internal consistency was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s α values. For factorial validity, the factor structures of the PHQ-4 and IES-6 scales were examined with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The relationships between demographic variables (gender, age, education and region of residence), Ebola experience, perceived Ebola threat and mental health symptoms were examined. Frequencies, proportions, 95% CI of proportions, as well as χ2 tests were generated to examine the relationships between sample characteristics and mental health symptoms. Univariate and multivariate binary logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between Ebola experience, perceived Ebola threat and mental health symptoms. We further examined the effect of Ebola experience, perceived Ebola threat and interaction between those two variables on mental health status by conducting a multivariable logistic regression controlling for potential confounders. To avoid multicollinearity, only composite scores were entered as predictors into the model. Sex, age, education and region were included because they have been associated with mental health symptoms in other studies. Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were calculated to measure the CFA model. Weighted cell count, percentages and ORs with 95% CIs are presented in the logistic regression tables.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Of 3640 individuals approached, 3564 (98%) consented to participate in the assessment. Sample characteristics by mental health symptoms are presented in table 1. The median age of respondents was 35 years (SD=15); 1774 (50%) were male. The sample comprised respondents from all four geographical regions in Sierra Leone: 798 (22%) from the west, north 1740 (49%), east 471 (13%) and south 555 (16%). Boosted district samples in Kambia and Port Loko, where cases were still being identified,9 resulted in a larger sample from the North. Of all respondents, 37% had no formal education, 20% had some primary school education and 43% had secondary or higher education.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics—National Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Survey, Sierra Leone, July 2015 (n=3564)

| Respondents N* (%†) |

Anxiety and depression (PHQ-4) | PTSD (IES-r) | |||||||||||||

| No symptom (N*=1982, 51.4%†) |

Any symptom/s (N*=1582, 48.6%†) | P value‡ | No symptom (N=880, 23.6%†) |

Any symptom/s (N=2684; 76.4%†) |

P value‡ | ||||||||||

| N* | N* | N* | N* | ||||||||||||

| Gender | 0.534 | 0.076 | |||||||||||||

| Male | 1774 (49%) | 983 | 48 | 45.9–50.5 | 791 | 49 | 47–51.7 | 425 | 46 | 42.7–49.5 | 1349 | 50 | 47.7–51.5 | ||

| Female | 1790 (51%) | 999 | 52 | 49.5–54.1 | 791 | 51 | 48.4–53.1 | 455 | 54 | 50.5–57.3 | 1335 | 50 | 48.5–52.3 | ||

| Age | 0.020 | 0.251 | |||||||||||||

| 15–24 years | 1203 (35%) | 710 | 37 | 34.5–38.9 | 493 | 33 | 30.8–35.2 | 310 | 37 | 33.2–39.8 | 893 | 34 | 32.6–36.2 | ||

| ≥25 years | 2360 (65%) | 1272 | 63 | 61.1–65.5 | 1089 | 67 | 64.8–69.2 | 570 | 64 | 60.2–66.8 | 1791 | 66 | 63.8–67.4 | ||

| Education§ | 0.857 | 0.111 | |||||||||||||

| None | 1424 (37%) | 807 | 37 | 34.8–39.2 | 617 | 36 | 34.1–38.6 | 351 | 37 | 33.9–40.5 | 1073 | 37 | 34.7–38.3 | ||

| Primary | 739 (21%) | 402 | 20 | 18.5–22.1 | 337 | 21 | 19.1–22.9 | 169 | 18 | 15.5–20.7 | 570 | 21 | 19.9–22.9 | ||

| ≥Secondary | 1394 (43%) | 768 | 43 | 40.4–45 | 626 | 43 | 40.4–4 5 | 358 | 45 | 41.2–48 | 1036 | 42 | 40.2–44 | ||

| Region | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| West | 798 (21%) | 515 | 26 | 23.7–27.7 | 283 | 15 | 13.5–16.8 | 290 | 32 | 28.5–34.7 | 508 | 17 | 15.7–18.5 | ||

| North | 1740 (34%) | 1006 | 36 | 34–38.4 | 734 | 32 | 29.8–34.1 | 383 | 30 | 27.3–33.5 | 1357 | 35 | 33.4–37 | ||

| East | 471 (23%) | 196 | 17 | 15.4–18.8 | 275 | 29 | 26.6–30.8 | 86 | 16 | 13.8–18.8 | 385 | 25 | 23.1–26.3 | ||

| South | 555 (23%) | 265 | 21 | 19.1–22.9 | 290 | 24 | 22.3–26.3 | 121 | 22 | 18.9–24.5 | 434 | 23 | 21.3–24.5 | ||

| Know someone who died from Ebola | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 1068 (31%) | 478 | 25 | 22.5–26.5 | 510 | 34 | 31.6–36.0 | 171 | 19 | 16.5–21.9 | 817 | 32 | 30.2–33.8 | ||

| No | 2476 (68%) | 1438 | 72 | 70.0–74.2 | 1038 | 64 | 61.9–66.5 | 673 | 77 | 73.7–79.5 | 1803 | 66 | 63.9–67.5 | ||

| Know someone quarantined for Ebola | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 1165 (34%) | 542 | 27 | 24.9–28.9 | 598 | 41 | 38.3–42.9 | 207 | 22 | 19.3–24.9 | 933 | 37 | 35.3–38.9 | ||

| No | 2378 (65%) | 1407 | 72 | 69.4–73.6 | 971 | 59 | 56.4–61.0 | 658 | 77 | 73.6–79.4 | 1720 | 62 | 60.0–63.6 | ||

| Composite Ebola experience: Know someone who died from Ebola and know someone quarantined for Ebola | |||||||||||||||

| None | 2168 (59%) | 1295 | 68 | 65.5–9.7 | 873 | 54 | 51.6–56.4 | <0.001 | 611 | 73 | 70.4–76.4 | 1557 | 57 | 55.2–59.0 | <0.001 |

| Only know someone died from Ebola | 199 (6%) | 84 | 6 | 4.5–6.5 | 80 | 5 | 4.3–6.5 | 32 | 5 | 3.1–5.9 | 132 | 6 | 4.8–6.6 | ||

| Only know someone quarantined for Ebola | 296 (9%) | 128 | 7 | 5.7–8.1 | 159 | 12 | 10.0–13.0 | 59 | 7 | 5.0–8.4 | 228 | 10 | 8.8–11.0 | ||

| Both experience | 869 (25%) | 392 | 20 | 18.3–21.9 | 428 | 29 | 27.0–31.2 | 137 | 15 | 13.0–17.8 | 683 | 27 | 25.6–29.0 | ||

| Ebola is no longer a threat in Sierra Leone | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Agree | 966 (30%) | 589 | 35 | 32.3–36.7 | 377 | 25 | 23.2–27.4 | 289 | 38 | 34.6–41.2 | 677 | 28 | 25.9–29.3 | ||

| Disagree | 2534 (69%) | 1355 | 63 | 60.9–65.3 | 1179 | 73 | 70.7–74.9 | 558 | 58 | 54.2–60.8 | 1976 | 71 | 69.3–72.7 | ||

| Ebola is no longer a threat in your district | 0.005 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Agree | 1188 (40%) | 676 | 42 | 39.5–44.1 | 512 | 37 | 34.8–39.4 | 337 | 47 | 43.2–50 | 851 | 37 | 35.6–39.2 | ||

| Disagree | 2309 (58%) | 1264 | 56 | 53.4–58 | 1045 | 61 | 58.7–63.3 | 509 | 49 | 45.4–52.2 | 1800 | 61 | 59.4–63 | ||

| Ebola is no longer a threat in your community | 0.007 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Agree | 1451 (45%) | 821 | 48 | 45.2–49.8 | 630 | 43 | 40.6–45.2 | 410 | 52 | 48.7–55.5 | 1041 | 43 | 41.3–45.1 | ||

| Disagree | 2062 (53%) | 1129 | 51 | 48.4–53 | 933 | 56 | 53.4–58 | 443 | 44 | 40.9–47.7 | 1619 | 56 | 54–57.8 | ||

| Ebola is no longer a threat in your household | 0.007 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Agree | 1543 (48%) | 864 | 50 | 47.4–52.0 | 679 | 45 | 43.0–47.6 | 421 | 53 | 49.5–56.3 | 1122 | 46 | 44–47.8 | ||

| Disagree | 1981 (51%) | 1092 | 49 | 46.5–51.1 | 889 | 54 | 51.3–56.1 | 439 | 44 | 40.8–47.6 | 1542 | 53 | 51.4–55.2 | ||

| Composite threat perception: Ebola is no longer a threat at any level | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Agree | 814 (26%) | 514 | 31 | 28.5–32.7 | 300 | 21 | 19.0–22.8 | 266 | 35 | 32.1–38.5 | 548 | 23 | 21.4–24.6 | ||

| Disagree | 2691 (72%) | 1433 | 67 | 65.2–69.4 | 1258 | 77 | 75.3–79.3 | 584 | 61 | 57.3–63.9 | 2107 | 76 | 74.2–77.4 | ||

*Frequencies are numbers without adjusting for sampling fractions.

†Percentages adjusted to take account of sampling fractions.

‡Pearson’s χ2 test, not taking missing value as categories.

§System missing values not presented; we excluded ‘don’t know’ responses and missing values.

IES-r, Impact of Event Scale-revised; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Nearly a third (31%) of respondents knew at least one person who died from Ebola. Similarly, 1165 participants (34%) knew at least one person who was quarantined. About a quarter (25%) of respondents knew someone who died from Ebola and someone who was quarantined. Nearly three quarters (72%) of respondents perceived an Ebola threat at one or more levels: in Sierra Leone (69%), their district (58%), their community (53%) or their household (51%).

Prevalence of symptoms

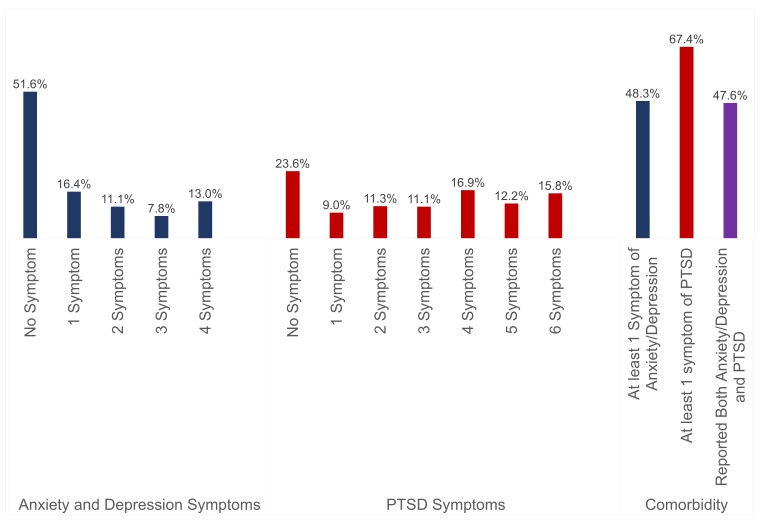

Figure 1 shows 48% (95% CI 46.8% to 50.0%) of respondents reported at least one symptom of anxiety or depression, with 6% (95% CI 5.4% to 7.0%) meeting the clinical cut-off definition. Of all respondents, 76% (95% CI 75.0% to 77.8%) reported one or more PTSD symptoms while 27% (95% CI 25.8% to 28.8%) met levels of clinical concern for PTSD and 16% (95% CI 14.7% to 17.1%) met levels of probable PTSD diagnosis. Among all respondents, 47% (95% CI 44.2% to 47.4%) reported both symptoms of anxiety and depression, and PTSD.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of anxiety-depression and PTSD symptoms—National Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Survey, Sierra Leone, July 2015 (N=3564). PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Multivariate analysis

Table 2A,B describes respondents’ experiences with Ebola and the association with anxiety and depression and PTSD symptoms, controlling for age, gender, region and education level. The experience of knowing someone who died from Ebola alone was not independently associated with anxiety and depression symptoms (adjusted OR (AOR) 1.1 95% CI 0.8 to 1.5, p=0.570) but was independently associated with PTSD symptoms (AOR 1.5 95% CI 1.0 to 2.2, p=0.035). Those participants who knew someone quarantined due to Ebola exposure alone were more likely to report symptoms of anxiety and depression (AOR 2.3 95% CI 1.7 to 2.9, p<0.001) and PTSD (AOR 2.0 95% CI 1.5 to 2.8, p<0.001) than those who did not. Respondents who had both experiences (that is, they knew at least one person who died from Ebola and someone quarantined) were also more likely to report symptoms of anxiety and depression (AOR 1.8 95% CI 1.5 to 2.2, p<0.001) and PTSD (AOR 2.3 95% CI 1.8 to 2.8, p<0.001) compared with those who did not report both. Those with any Ebola experience were more likely to report anxiety and depression symptoms than those who had no Ebola experience (AOR 1.8 95% CI 1.6 to 2.0, p<0.001) and were more likely to report PTSD symptoms than those with no Ebola experience (AOR 2.01 95% CI 1.69 to 2.38, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Effect of Ebola experience on mental health outcomes—National Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Survey, Sierra Leone, July 2015 (n=3564)

| Anxiety and depression symptoms (PHQ-4) | PTSD symptoms (IES-r) | |||||||||

| N* | %* | P value | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | N* | %* | P value† | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| A | ||||||||||

| None (N*=2094) | 907 | 43.3 | Reference | Reference | 1506 | 71.9 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Only know someone who died (N*=187) | 91 | 48.7 | 0.570 | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.7) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) | 150 | 80.2 | 0.035 | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.3) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.2) |

| Only know someone quarantined (N*=315) | 194 | 61.6 | <0.001 | 2.1 (1.6 to 2.0) | 2.3 (1.7 to 2.9) | 261 | 82.9 | <0.001 | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.5) | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.8) |

| Both experiences (N*=841) | 489 | 58.1 | <0.001 | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.1) | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.2) | 719 | 85.5 | <0.001 | 2.3 (1.8 to 2.8) | 2.3 (1.8 to 2.8) |

| B | ||||||||||

| None (N*=2094) | 907 | 43.3 | Reference | Reference | 1506 | 71.9 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Know someone who died or is quarantined (N*=1444) | 809 | 56.0 | <0.001 | 1.66 (1.45 to 1.90) | 1.8 (1.55 to 2.04) | 1196 | 82.8 | <0.001 | 1.88 (1.59 to 2.22) | 2.01 (1.69 to 2.38) |

Adjusted for age group, region of residence, gender and education.

*Frequency and proportions adjusted to account for sampling fractions; we excluded ‘don’t know’ responses and missing values.

†P values for Wald’s χ2 test.

AOR, adjusted OR; IES-r, Impact of Event Scale-revised; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table 3 presents the relationship between perceived Ebola threat and reported symptoms of anxiety and depression and PTSD. Respondents who perceived some ongoing threat of Ebola were more likely to report symptoms of anxiety-depression (AOR 1.69 95% CI 1.44 to 1.98, p<0.001) and PTSD (AOR 1.86 95% CI 1.56 to 2.21, p<0.001) compared with those who did not.

Table 3.

Effect of Ebola risk perception on mental health outcomes— National Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Survey, Sierra Leone, July 2015 (n=3564)

| Ebola risk perception at | Anxiety and depression symptoms (PHQ-4) | PTSD symptoms (IES-r) | ||||||||

| N* | %* | P value† | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | N* | %* | P value† | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| National level (n=2416) | 1256 | 52.0 | <0.001 | 1.58 (1.37 to 1.83) | 1.58 (1.36 to 1.83) | 1933 | 80.0 | <0.001 | 1.70 (1.44 to 2.00) | 1.64 (1.38 to 1.94) |

| District level (n=2078) | 1053 | 50.6 | <0.001 | 1.23 (1.08 to 1.41) | 1.31 (1.14 to 1.51) | 1666 | 80.2 | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.33 to 1.83) | 1.65 (1.40 to 1.95) |

| Community level (n=1894) | 962 | 50.8 | 0.001 | 1.22 (1.07 to 1.39) | 1.27 (1.10 to 1.46) | 1520 | 80.3 | <0.001 | 1.52 (1.30 to 1.78) | 1.62(1.37 to 1.91) |

| Household level (n=1824) | 927 | 50.8 | 0.001 | 1.21 (1.06 to 1.38) | 1.26 (1.09 to 1.45) | 1452 | 79.6 | <0.001 | 1.39 (1.19 to 1.68) | 1.45 (1.23 to 1.71) |

| Composite risk perception (n=2573) | 1335 | 51.9 | <0.001 | 1.69 (1.45 to 1.97) | 1.69 (1.44 to 1.98) | 2063 | 80.2 | <0.001 | 1.93 (1.63 to 2.28) | 1.86 (1.56 to 2.21) |

Adjusted for age group, region of residence, gender and education.

*Frequency and proportions adjusted to account for sampling fractions; we excluded ‘don’t know’ responses and missing values.

†P values for Wald’s χ2 test.

AOR, adjusted OR; IES-r, Impact of Event Scale revised; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table 4 presents multivariate analyses of the associations between Ebola experience and perceived Ebola threat and symptoms of anxiety and depression and PTSD, adjusting for gender, age, region and education levels. Ebola experience and perceived Ebola threat were independently associated with anxiety and depression symptoms as well as PTSD symptoms. In addition, the interaction between Ebola related experience and risk perception was independently associated with both anxiety-depression and PTSD symptoms: participants who had Ebola experience and also perceived ongoing Ebola threat were more likely to report symptoms of anxiety-depression (AOR 1·47 95% CI 1·07 to 2·03, p=0.018) and PTSD symptoms (AOR 1·44 95% CI 1·0 to 2·07, p=0.049).

Table 4.

Effect of Ebola experience and risk perception on mental health outcomes—National Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Survey, Sierra Leone, July 2015 (n=3564)

| Anxiety and depression symptoms (PHQ-4) | PTSD symptoms (IES-r) | |||||||||

| N* | %* | P value | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | N* | %* | P value† | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Know someone who died or was quarantined (N*=1444) | 809 | 56.0 | 0.045 | 1.31 (1.00 to 1.72) | 1.33 (1.01 to 1.75) | 1196 | 82.8 | 0.007 | 1.47 (1.10 to 1.96) | 1.51 (1.12 to 2.02) |

| Composite risk perception(N*=2573) | 1335 | 51.9 | <0.001 | 1.47 (1.20 to 1.80) | 1.45 (1.18 to 1.77) | 2063 | 80.2 | <0.001 | 1.74 (1.41 to 2.14) | 1.68 (1.36 to 2.09) |

| Ebola experience × composite risk perception (N*=1072) | 646 | 60.3 | 0.018 | 1.37 (1.00 to 1.87) | 1.47 (1.07 to 2.03) | 924 | 86.2 | 0.049 | 1.36 (0.95 to 1.94) | 1.44 (1.00 to 2.07) |

*Frequency and proportions adjusted to account for sampling fractions; we excluded ‘don’t know’ responses and missing values.

†P values for Wald’s χ2 test.

AOR, adjusted OR (adjusted for age group, region of residence, gender and education); IES-r, Impact of Event Scale-revised; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Discussion

In a national sample of Sierra Leoneans after more than a year of the unprecedented Ebola epidemic, nearly half of all respondents reported at least one symptom of anxiety or depression and three quarters expressed PTSD symptoms. Most respondents reported between one and four symptoms. After adjusting for sociodemographic variables, we found that persons with any level of Ebola experience were more likely to report symptoms of anxiety-depression and PTSD. Even though expression of one or more symptoms was widespread among our sample, a lower proportion of respondents met the clinical cut-off scores for anxiety-depression (5%–7%) and probable diagnosis for PTSD (15%–17%). The proportion of respondents who exhibited clinical level symptoms of anxiety-depression may be considered ‘lower than expected’ given the magnitude and duration of the epidemic, but may also point to a culture of resiliency among Sierra Leoneans.40 On the other hand, we documented substantial PTSD, which is a public health concern that may require targeted mental health interventions at the individual level and community level for those with some personal Ebola experience.

A national assessment of the mental health impact of the 2003 SARS epidemic in Taiwan, using a different scale than in our current study, found 4% prevalence of depression after the epidemic ended.3 Another population-based survey in Taiwan revealed 12% prevalence of psychiatric morbidity following SARS.9 In Singapore, a community-based sample detected that a quarter of all respondents had clinical levels of PTSD symptoms.11 Other mental health assessments with SARS survivors4 8 and HCWs5 documented similar or higher clinical PTSD levels compared with our current assessment. One study found that HCWs with a history of mental illness before SARS were more likely to report new onset following the epidemic.7 In our assessment, we cannot determine how past mental health history of PTSD in Sierra Leone, especially due to the prolonged civil war from 1992 to 2002, may have influenced the levels of clinical PTSD concern we detected.

Similar to SARS, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic was associated with psychological distress among the general population,13 14 20 family members of hospitalised patients with H1N121 and HCWs.18 In some instances, prevalence of H1N1-related anxiety was higher among those who had greater intolerance of uncertainty.15 17 Additional research is required to better understand the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and quarantine experience during large-scale infectious disease outbreaks. An assessment with HCWs in China found that being quarantined and having perceived threat of SARS were associated with high depressive symptoms several years after the epidemic ended.10 In a separate study, H1N1 quarantine experience did not predict elevated PTSD levels while dissatisfaction with control measures was a better predictor.16

To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has assessed the mental health impact of the protracted Ebola epidemic at population levels in Sierra Leone, Liberia or Guinea. A limited number of studies have examined population-level mental health in other African countries. One such study in a predominantly rural community in Ethiopia found that 14% of the population expressed clinical levels of mild depressive, anxiety and somatic symptoms.41 On the other hand, a wide variety of studies have examined anxiety and depression in high-risk populations in Africa, including patients with tuberculosis in Ethiopia42 and Angola,43 Rwandans who had experienced genocide,44 and Nigerian prison inmates.45 Findings of varying levels of mental health symptomology from these studies suggest that further investigations may be required to better understand specific mental health impact of the Ebola epidemic on directly affected persons such as Ebola survivors.

In a systematic review, adverse mental health impact has been documented among conflict-affected persons.24 In Sierra Leone, during protracted civil conflict, exposure to traumatic events was associated with non-specific physical ailments.46 High prevalence of traumatic experiences and psychiatric sequelae has also been documented among Sierra Leonean refugees.25 Among war affected youth in Sierra Leone, social disorder and perceived stigma contributed to both externalising and internalising problems.47 Former child soldiers in Sierra Leone saw reliable improvement in PTSD symptoms over time, suggesting that a supportive environment may encourage resilience.48

A key recommendation in previous studies and WHO guidance is to integrate mental health into primary healthcare services.49 One study found global return on investments for scaling up treatment for depression and anxiety.50 An example of such effort is in progress in Sierra Leone wherein public health nurses are trained to screen patients for possible mental health needs.51 The WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme emphasises that scaling up mental health services is a joint responsibility that requires collaboration from governments, health professionals, donors, civil society, communities and families.52

Limitations

Although a random national sample was obtained, our sample is not necessarily nationally representative. The sample had a higher proportion of respondents with any education compared with the general population.53 However, we did not find any association between education level and mental health symptoms, suggesting that this may not have influenced our findings. We acknowledge the necessity of validating survey instruments before using them in a new cultural context. Although PHQ-4 and IES-r have been widely used globally,31–37 54 neither has been validated nor used in Sierra Leone prior to this study. We therefore do not know the validity of clinical cut-off scores for our sample. To the best of our knowledge, PHQ-4 and IES-r (or the shortened form in this assessment) have not been used to measure population-level symptoms of mental health in any similar setting; making it impossible to compare our results to similar populations elsewhere. However, we found both had acceptable internal reliability and factorial validity. In the current survey, the PHQ-4 instrument demonstrated acceptable internal reliability (Cronbach’s α=0.78) and good factorial validity (GFI=0.999, CFI=0.999, RMSEA=0·030). The shortened IES-6 scale used in the present study demonstrated acceptable internal reliability (Cronbach’s α=0.78) and good factorial validity (GFI=0·998, CFI=0·998, RMSEA=0.023). In addition, the national sample was not designed to produce specific estimates for directly affected persons such as Ebola survivors, families of Ebola victims and quarantined persons. Moreover, there are no baseline/historical data available for comparisons. We also did not measure the effects of exposure to Sierra Leone’s civil conflict on long-term PTSD outcomes on the population prior to Ebola.

Conclusions

Overall, our findings underscore the feasibility and importance of monitoring and addressing mental health during public health outbreaks as well as building capacity to do so as part of preparedness efforts. Use of brief mental health screeners during outbreak response could increase the ability to identify and address the needs of high-risk groups. We have demonstrated the ability to rapidly administer PHQ-4 and IES-6 at a population-level to identify factors associated with mental health symptomology towards the end of an unprecedented infectious disease epidemic. Preventing, detecting and responding to mental health conditions should be an important component of global health security efforts.55 56

bmjgh-2017-000471supp001.pdf (215KB, pdf)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Sierra Leoneans who participated in this assessment and provided responses in the midst of an unprecedented epidemic. The authors also thank the data collection team from FOCUS 1000 for their diligent efforts in ensuring data quality and the Government of Sierra Leone and their national and international partners in the response. Finally, we dedicate this article to the memory of our co-author, Dr. Foday Dafae, the late Director of Disease Prevention and Control in Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation, in honor of his years of service to the people of Sierra Leone.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: MFJ, RB, AOL and PS led the overall study design with substantial contributions made by the other coauthors. PS, MFJ and MBJ were responsible for training the data collectors and supervised all data collection and data management efforts. WL led all data analyses. All authors contributed equally to the iterative interpretation of the results and the writing and preparation of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (10.13039/100000030).

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data sharing agreement has been developed for the Ebola KAP Assessments in Sierra Leone. All requests to access the data must be processed through the multi-partner data sharing mechanism. Reasonable data accessibility requests should be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Ebola situation reports. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204714/1/ebolasitrep_30mar2016_eng.pdf (accessed Apr 2016).

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa - case counts. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/case-counts.html (accessed Apr 2016).

- 3.Ko CH, Yen CF, Yen JY, et al. . Psychosocial impact among the public of the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;60:397–403. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01522.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mak IW, Chu CM, Pan PC, et al. . Long-term psychiatric morbidities among SARS survivors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2009;31:318–26. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lung FW, Lu YC, Chang YY, et al. . Mental symptoms in different health professionals during the SARS attack: a follow-up study. Psychiatr Q 2009;80:107–16. 10.1007/s11126-009-9095-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mihashi M, Otsubo Y, Yinjuan X, et al. . Predictive factors of psychological disorder development during recovery following SARS outbreak. Health Psychol 2009;28:91–100. 10.1037/a0013674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lancee WJ, Maunder RG, Goldbloom DS. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among Toronto hospital workers one to two years after the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv 2008;59:91–5. 10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee AM, Wong JG, McAlonan GM, et al. . Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatry 2007;52:233–40. 10.1177/070674370705200405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng EY, Lee MB, Tsai ST, et al. . Population-based post-crisis psychological distress: an example from the SARS outbreak in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2010;109:524–32. 10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60087-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, et al. . Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr Psychiatry 2012;53:15–23. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sim K, Huak Chan Y, Chong PN, et al. . Psychosocial and coping responses within the community health care setting towards a national outbreak of an infectious disease. J Psychosom Res 2010;68:195–202. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nickell LA, Crighton EJ, Tracy CS, et al. . Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ 2004;170:793–8. 10.1503/cmaj.1031077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeung NCY, Lau JTF, Choi KC, et al. . Population responses during the pandemic phase of the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 Epidemic, Hong Kong, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23:813–5. 10.3201/eid2305.160768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liao Q, Cowling BJ, Lam WW, et al. . Anxiety, worry and cognitive risk estimate in relation to protective behaviors during the 2009 influenza A/H1N1 pandemic in Hong Kong: ten cross-sectional surveys. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:169 10.1186/1471-2334-14-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taha S, Matheson K, Cronin T, et al. . Intolerance of uncertainty, appraisals, coping, and anxiety: the case of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Br J Health Psychol 2014;19:592–605. 10.1111/bjhp.12058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Xu B, Zhao G, et al. . Is quarantine related to immediate negative psychological consequences during the 2009 H1N1 epidemic? Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011;33:75–7. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taha SA, Matheson K, Anisman H. H1N1 was not all that scary: uncertainty and stressor appraisals predict anxiety related to a coming viral threat. Stress Health 2014;30:149–57. 10.1002/smi.2505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuishi K, Kawazoe A, Imai H, et al. . Psychological impact of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 on general hospital workers in Kobe. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2012;66:353–60. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2012.02336.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams L, Regagliolo A, Rasmussen S. Predicting psychological responses to influenza A, H1N1 ("swine flu"): the role of illness perceptions. Psychol Health Med 2012;17:383–91. 10.1080/13548506.2011.626564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cowling BJ, Ng DM, Ip DK, et al. . Community psychological and behavioral responses through the first wave of the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic in Hong Kong. J Infect Dis 2010;202:867–76. 10.1086/655811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elizarrarás-Rivas J, Vargas-Mendoza JE, Mayoral-García M, et al. . Psychological response of family members of patients hospitalised for influenza A/H1N1 in Oaxaca, Mexico. BMC Psychiatry 2010;10:104 10.1186/1471-244X-10-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodwin R, Haque S, Neto F, et al. . Initial psychological responses to Influenza A, H1N1 ("Swine flu"). BMC Infect Dis 2009;9:166 10.1186/1471-2334-9-166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gross R, Neria Y. Posttraumatic stress among survivors of bioterrorism. JAMA 2004;292:566 10.1001/jama.292.5.566-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steel Z, Chey T, Silove D, et al. . Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009;302:537–49. 10.1001/jama.2009.1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fox SH, Tang SS. The Sierra Leonean refugee experience: traumatic events and psychiatric sequelae. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000;188:490–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Jong K, Mulhern M, Ford N, et al. . The trauma of war in Sierra Leone. The Lancet 2000;355:2067–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02364-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shultz JM, Baingana F, Neria Y. The 2014 Ebola outbreak and mental health: current status and recommended response. JAMA 2015;313:567–8. 10.1001/jama.2014.17934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keita MM, Taverne B, Sy Savané S, et al. . Depressive symptoms among survivors of Ebola virus disease in Conakry (Guinea): preliminary results of the PostEboGui cohort. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:127 10.1186/s12888-017-1280-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ji D, Ji YJ, Duan XZ, et al. . Prevalence of psychological symptoms among Ebola survivors and healthcare workers during the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. Oncotarget 2017;8:12784–91. 10.18632/oncotarget.14498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gershon R, Dernehl LA, Nwankwo E, et al. . Experiences and psychosocial impact of West Africa Ebola Deployment on US Health Care Volunteers. PLoS Curr 2016;8 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.c7afaae124e35d2da39ee7e07291b6b5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. . An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 2009;50:613–21. 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Löwe B, Wahl I, Rose M, et al. . A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord 2010;122:86–95. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giorgi G, Fiz Perez FS, Castiello D’Antonio A, et al. . Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale-6 in a sample of victims of bank robbery. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2015;8:99–104. 10.2147/PRBM.S73901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The impact of event scale revised : Wilson J, Keane T, Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Guildford Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Motlagh H. Impact of event scale-revised. J Physiother 2010;56:203 10.1016/S1836-9553(10)70029-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asukai N, Kato H, Kawamura N, et al. . Reliability and validity of the Japanese-language version of the impact of event scale-revised (IES-R-J): four studies of different traumatic events. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002;190:175–82. 10.1097/00005053-200203000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale - revised. Behav Res Ther 2003;41:1489–96. 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization. Ebola situation report. http://apps.who.int/ebola/current-situation/ebola-situation-report-29-july-2015 (accessed Apr 2016).

- 39.Government of Sierra Leone. Sierra Leone emergency management program standard operating procedure for management of quarantine. http://www.nerc.sl/sites/default/files/docs/GOSL%20QUARANTINE%20SOP%20final%2028_10-14.pdf (accessed Apr 2016).

- 40.Betancourt TS, Khan KT. The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: protective processes and pathways to resilience. Int Rev Psychiatry 2008;20:317–28. 10.1080/09540260802090363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fekadu A, Medhin G, Selamu M, et al. . Population level mental distress in rural Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:1–13. 10.1186/1471-244X-14-194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duko B, Gebeyehu A, Ayano G. Prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety among patients with tuberculosis at WolaitaSodo University Hospital and Sodo Health Center, WolaitaSodo, South Ethiopia, Cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2015;15:214 10.1186/s12888-015-0598-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xavier PB, Peixoto B. Emotional distress in Angolan patients with several types of tuberculosis. Afr Health Sci 2015;15:378–84. 10.4314/ahs.v15i2.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rugema L, Mogren I, Ntaganira J, et al. . Traumatic episodes and mental health effects in young men and women in Rwanda, 17 years after the genocide. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006778 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osasona SO, Koleoso ON. Prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety disorder in a sample of inmates in a Nigerian prison. Int J Psychiatry Med 2015;50:203–18. 10.1177/0091217415605038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Jong K, Mulhern M, Ford N, et al. . The trauma of war in Sierra Leone. Lancet 2000;355:2067–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02364-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Betancourt TS, McBain R, Newnham EA, et al. . Context matters: community characteristics and mental health among war-affected youth in Sierra Leone. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2014;55:217–26. 10.1111/jcpp.12131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Betancourt TS, Newnham EA, McBain R, et al. . Post-traumatic stress symptoms among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone: follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry 2013;203:196–202. 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.113514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.World Bank Group. Out of the shadows: making mental health a global development priority. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/391171465393131073/0602-SummaryReport-GMH-event-June-3-2016.pdf (accessed Apr 2016).

- 50.Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, et al. . Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:415–24. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30024-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.World Health Organization. Psychiatric nurses receive mhGAP intervention guide. http://www.afro.who.int/en/sierra-leone/press-materials/item/4508-psychiatric-nurses-receive-mhgap-intervention-guide.html (accessed Apr 2016).

- 52.World Health Organization. mhGAP mental health gap action programme: scaling up care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders. http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/mhGAP/en (accessed Apr 2016). [PubMed]

- 53.Statistics Sierra Leone. Demographic and health survey 2013. http://www.mamaye.org/sites/default/files/evidence/SSL%20%26%20ICF_2014_Sierra%20Leone%20DHS%202013.pdf (accessed Apr 2016).

- 54.Warsini S, Buettner P, Mills J, et al. . Psychometric evaluation of the Indonesian version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2015;22:251–9. 10.1111/jpm.12194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. . The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 2009;18:23–33. 10.1017/S1121189X00001421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heymann DL, Chen L, Takemi K, et al. . Global health security: the wider lessons from the west African Ebola virus disease epidemic. Lancet 2015;385:1884–901. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60858-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2017-000471supp001.pdf (215KB, pdf)