Abstract

Changing alcohol consumption has led to a three- to fivefold increase in liver deaths in the UK and Finland, and a three- to fivefold decrease in France and Italy. Increasing consumption from a low baseline has been driven by fiscal, marketing and commercial factors – some of which have occurred as a result of countries joining the EU. In contrast consumption has fallen from previously very high levels as a result of shifting social and cultural factors; a move from rural to urban lifestyles and increased health consciousness. The marketing drive in these countries has had to shift from a model based on quantity to one based on quality, which means that health gains have occurred alongside a steady improvement in the overall value of the wine industry. Fiscal incentives – minimum pricing, restricting cross border trade and more volumetric taxation could aid this shift. A healthier population and a healthy drinks industry are not incompatible.

Key Words: alcohol, drinks industry, liver, mortality, wine

Introduction

Europe is the heaviest drinking region in the world and the evidence detailing the burden of ill health and the economic costs attributable to excessive consumption of alcohol is extensive. The World Health Organization recognises alcohol as the third leading risk factor for poor health in Europe, resulting in 200,000 deaths each year with a cost to society of around 125 billion, or 1.3% of gross domestic product.1,2

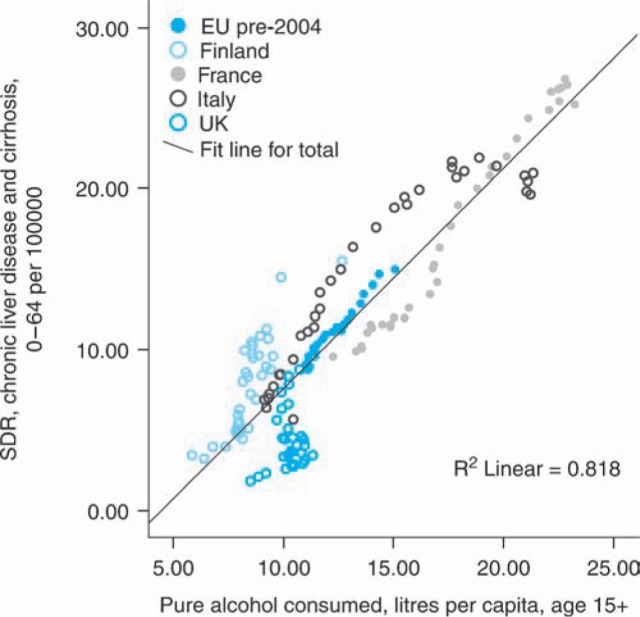

Different varieties of harm result from different patterns of drinking alcohol; acute intoxication causes people to put themselves and others at risk and is implicated in sexual and other violence, suicide, accidental death and trauma. Regular heavy drinking can lead to alcohol dependency and chronic ill health. Alcohol is metabolised by the liver, and regular heavy intake causes progressive fibrosis, cirrhosis, liver failure and death. Alcohol-related disease is the most common cause of cirrhosis. Liver death rates are a reliable indicator of the harm caused by regular heavy drinking and there is a strong relationship between these rates (liver SDR) and overall alcohol consumption which becomes stronger as overall consumption increases (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

The relationship between standard liver death rate (SDR) (per 100,000) and overall alcohol consumption (pure alcohol litres per capita, age 15+) in the four countries in the EU (pre-2004) with the largest rises or falls in liver deaths between 1970 and 2008. Data from the World Health Organization, European Health for All database (HFA-DB): http://data.euro.who.int/hfadb/

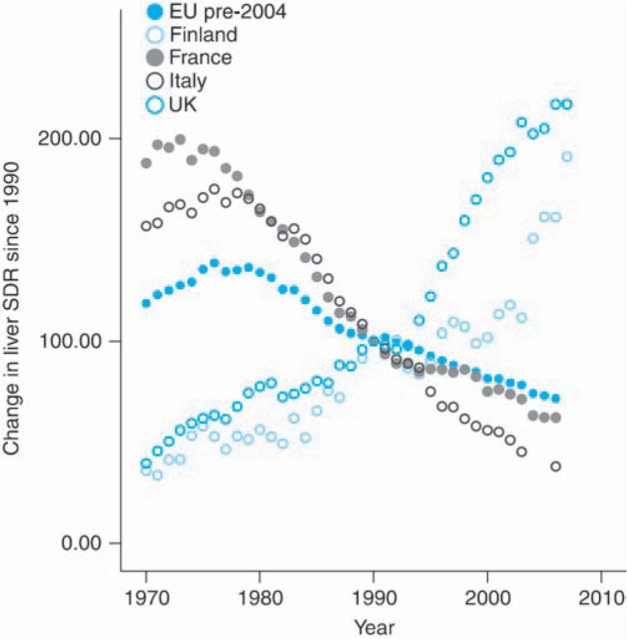

Over the last 30 years liver death rates in the European Union (EU) have gradually declined in response to changing patterns of alcohol intake. The EU liver death rate was 13.25 in 1970 and 8.01 in 2007 (for pre-2004 EU member states) – a reduction of 60%. But this overall decline conceals very large differences between member states. France and Italy, the countries with the largest decline in liver deaths, have seen a three- to fourfold reduction in liver mortality whereas the UK and Finland have seen liver deaths rise by more than fivefold over the same period of time (Fig 2). These are very dramatic changes in alcohol-related harm and the purpose of this study is to examine possible reasons for these changes, and the lessons they may hold for alcohol policy in the EU.

Fig 2.

Trends in Finland, France, Italy, UK and the EU (pre-2004) overall in standard liver death rate (SDR) (under the age of 65) over time between 1970 and 2008. Data from the World Health Organization, European Health for All database (HFA-DB) and has been normalised to 100% in 1990.

Drinking cultures

Across the EU there are numerous cultural behaviours related to alcohol consumption and the nature of the resulting harm differs in terms of its impact on the individual, society and the economy. A traditional distinction has been drawn between northern European countries and their southern European counterparts in terms of alcohol consumption and drinking patterns, and it is tempting to place the origin for these differences back in antiquity. In the epic Babylonian poem Gilgamesh (2700 BC) the fall of the hero Enkidu was precipitated by seduction into drunkenness: ‘Enkidu drank the beer – seven jugs and became expansive and sang with joy, he was elated and his face glowed’. But later he curses, ‘May dregs of beer stain your beautiful lap, may a drunk soil your festal robe with vomit…’. The regular drinking of wine with meals was contrasted with barbarian drinking habits by Diodorus Siculus and Tacitus in the 1st centuries BC and AD, and by Saints Boniface and Bede in the 9th century AD. Epic feats of drunkenness are as much a feature of Celtic and Viking poetry as the battles which they celebrated and remain a feature of Anglo Saxon and Celtic society to this day.

Whatever the underlying reasons, these cultural differences are real. In the Eurobarometer alcohol survey of 2002, Ireland, the UK and Finland had the highest number of occasions on which people thought they ‘had drunk too much’ and had the lowest percentage of alcohol consumption with meals, with Italy having the highest.3 Northern European countries have historically restricted demand with rigid controls on the supply of alcohol including:

restrictions on the availability of alcohol (both for on-trade and off-trade sale)

restrictions on the number of premises licensed to sell alcohol

limited hours of trade and high prices

state monopolies on alcohol production and trade.4

In stark contrast, southern European countries had limited policies in place to restrict the availability of alcohol before the 1980s.5 The nature of the alcohol industry in southern Europe is also different, with a large variety of diverse wine producers, and local or regionally produced wines for local consumption.

UK

Changes in alcohol consumption in the UK have been driven by cultural and market factors. Marketing – the art of selling – has four basic principles: the four Ps. Place, product, price and promotion have all changed in association with a shift from local pubs to sales from supermarkets and local shops. Since 1970 sales of wine and spirits increased – wine more than sixfold and spirits twofold.6 Sales of strong lager increased 15-fold and cider sixfold, whereas sales of normal strength beer and lager fell by around 10%. The doubling of wine consumption was influenced by foreign holidays, globalisation and EU membership requiring harmonisation of duty on wine. But the rise of supermarkets also resulted in marked changes in the way that alcohol was advertised, to the extent that promotions are now used to drive footfall into stores, and stacks of cheap white wine are now routinely placed throughout the store to facilitate impulse buying.6 This is an irresponsible way to sell a toxic dependence-inducing drug and it has been remarked that ‘supermarkets are exhibiting the morality of a crack dealer’.7

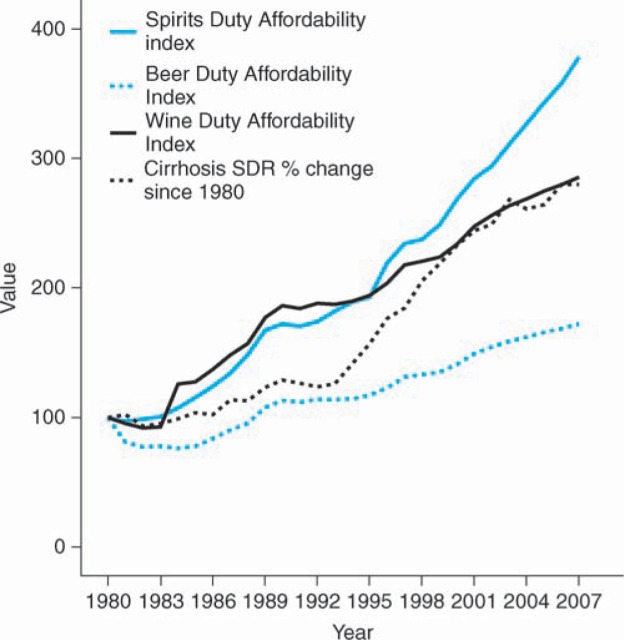

The early 1990s saw the conjunction of plummeting whisky sales as an older generation moved on and the emergence of a new and initially alcohol averse youth culture, leading to intense and successful industry lobbying on alcohol taxation.6,8 Duty on spirits was reduced for the next 15 years. Since 1980, spirits have become 350% more affordable, wine 270% and beer 170% (Fig 3).6 The steep change came in the mid-1990s as a direct result of industry pressure; drinks became even cheaper and stronger and liver death rates escalated. Furthermore, over the course of the decade alcohol advertising expenditure increased by two thirds and the marketing focus shifted towards young people, with the introduction of alcopops, ‘vertical drinking’ pubs and alcohol sponsorship of music festivals. As a result, the average alcohol consumption of 11–15-year-old children increased by two thirds and ‘binge Britain’ was born.9 A recent House of Commons report has outlined the abject failure of self-regulatory codes to protect young people from alcohol marketing.7

Fig 3.

Effect of income inflation on the levels of duty on various alcoholic beverages since 1980. Trends in the duty on various alcoholic beverages were adjusted for changes in real disposable income – using a methodology developed by the NHS Information Centre (Statistics on Alcohol 2008) to calculate an Alcohol Affordability Index. The Beverage Duty Affordability Index is normalised to 100% in 1980 and was calculated as follows (using spirits as an example): Spirits Duty Index (SDI) = spirits duty normalised in 1980; Relative Spirits Duty Index (RSDI) = SDI/Retail Price Index (RPI) ×100; Spirits Duty Affordibility Index (SDAI) = Real Disposable Income (RDI)/RSDI × 100. Beverage duty data from Ref 6. RPI and RDI from Statistics on Alcohol 2008.

Finland

Finland has also seen profound changes in the previously very tight fiscal regulation of alcohol largely as a result of joining the EU. Finland was forced to withdraw its alcohol monopoly on the production, import, export and wholesale of alcohol upon entering the EU in 1995. Then in 2004 Finland was forced to lower alcohol taxation to avoid significant loss to the national tax base. While this move was prompted by fiscal rather than public health objectives, it would arguably never have happened had the EU not introduced lighter controls on imports for personal use.10 Consumption jumped by 10% in 2004 and alcohol-induced liver disease increased by 29% on the previous year.11 Just like the UK, Finland has seen changes in the type of alcohol consumed, with a threefold increase in wine consumption, a twofold increase in beer consumption and a smaller 30% rise in spirits consumption since 1970.

Given the relaxation in the previously relatively tough controls on alcohol in both countries it would be astonishing if liver deaths had not increased in the UK and Finland. But how can the marked fall in alcohol consumption and liver deaths in France and Italy be explained?

Southern Europe

The wine-producing countries of southern Europe, with the exception of Greece, have recorded declining trends in alcohol consumption since the 1960s – long before alcohol control measures were implemented. Total alcohol consumption in France has fallen by 12 litres per capita since the 1950s while the trend in Italy began later, dropping from 15.9 litres of pure alcohol per capita in 1970 to 6.9 litres in 2005.12,13 This drop was due to an overwhelming decrease in wine consumption, and is likely due to a variety of factors which may be thought of in phases.

The link between cirrhosis and alcohol intake was only fully established in the 1960s. As such, alcohol was not a major concern for institutions controlling public health or public order.13 Wine consumption in Italy was closely linked to rural lifestyles and rural–urban migration led to less wine drinking.14 Similar trends occurred in France.15 The move to urbanisation was the first phase, and was most active in the 1960s and 70s but consumption has continued to fall well into the 1990s and beyond – other factors were clearly also playing a part.

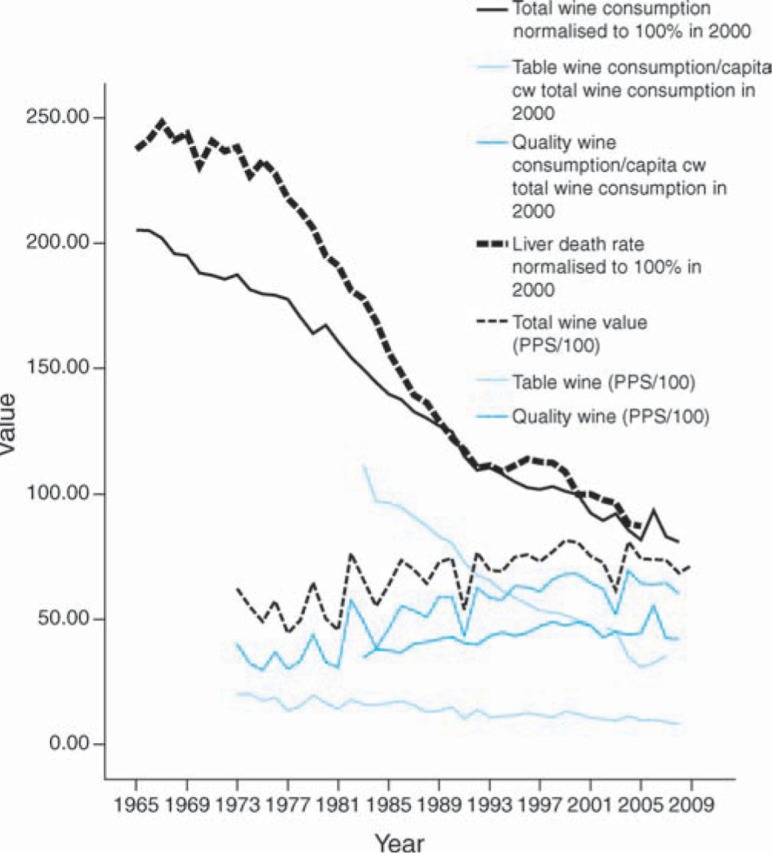

Levels of wine production remained high in France and Italy. Measures taken by the European Commission in the late 1970s and early 1980s to reduce wine production and improve the quality of the product as part of the common agricultural policy cannot alone account for the drop in internal consumption.16 Rather a move to quality of production was a reaction by the industry to consumer choice and reduced demand.16 Skog identifies the middle classes as the pioneers of change in France, and notes that they were already drinking less than other groups, preferring to opt for high-quality options instead – ‘bottles with corks’ as opposed to large plastic containers of cheap ‘plonk’ (Fig 4).17, 18 This is good news for the wine industry and suggests that profitability and improved health can go hand in hand by moving towards quality and away from quantity – a lesson that UK supermarkets would do well to learn from their French and Italian counterparts.

Fig 4.

Liver death rates and the shift from table wine to higher quality wine consumption in France. Wine consumption data and liver death rate are given in comparison with the year 2000. Wine value is the value of total wine production given in EU Purchasing Power Standard (PPS) – exports increased from 12% to 31% over the same period. Data are from Eurostat (http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu) and the World Health Organization Statistical Information System (www.who.int/whosis).

Perhaps another reason for change was that most people in these countries had a friend or relative suffering the health consequences of alcohol – something that has only really started in the UK over the last five or six years. Coupled with health campaigns in both countries, the image of wine drinking was no longer seen as a source of health and happiness and did not conform to the burgeoning health consciousness trends.13

In terms of emerging trends in Italy, experts have identified the co-existence of two parallel alcohol consumption patterns: the traditional Mediterranean drinking pattern on the one hand, and a second pattern found among younger drinkers with 24% of 20–24-year-old Italians reporting binge drinking on occasion.19 In recent years alcoholic beverages have become more affordable for young Italians, with experts again noting an overt marketing strategy targeting young people.19 There has been an associated increase in the social harm from alcohol and the policy reaction has included local restrictions and bans on the sale of alcoholic beverages to minors and regulations aimed at decreasing the availability of alcohol in public places and at public events.19 Southern Europe is clearly not immune to northern tendencies. This is hidden within the general trend towards lower per capita consumption, but is starkly apparent when you look at patterns of consumption by age group.

Discussion and implications for policy

Despite increasing homogenisation of alcohol consumption in Europe, the trends in each of the four countries examined indicate that there are a number of different drivers that impact upon levels of alcohol-attributable liver mortality. In northern Europe, a combination of primarily economic and market factors have contributed to increased levels of total consumption and its associated harm, while in southern Europe social changes have contributed to the downward trend in alcohol-related liver deaths. Nevertheless, consumption remains high and emerging trends, such as those seen among young people in Italy, mean that policy action needs to be taken to ensure that the decrease in liver cirrhosis is maintained. In global terms, Europe's alcohol control policies are still not proportionate to the level of overall harm from alcohol, and the convergence in total consumption remains at a level that is too high.

Taxation policy emerged as a crucial lever impacting upon alcohol consumption. In both the UK and Finland lower tax rates have helped to contribute to making alcohol more affordable. In an EU context the relaxation of restrictions in cross border trade has had very deleterious effects in terms of taxation, price and alcohol-related ill health.

The marketing activities of the alcohol industry and retailers have had a huge impact on young people.20 Self-regulation in this respect has failed and other mechanisms need to be explored. The UK House of Commons Health Committee has recommended a fully independent regulatory authority to control alcohol marketing, and the EU would do well to examine these proposals carefully.

However, the reduction in liver deaths in France has occurred alongside an increase in profitability of the wine industry as a result of the industry model shifting from one based on quantity (the current UK model) to one based on quality. The EU, in the form of the common agricultural policy, may have had a beneficial effect, driving down the amount of cheap alcohol that is produced in order to protect farmers. Further fiscal measures could help – volumetric (as opposed to value added) taxation and minimum pricing both favour quality over quantity.

Given the tight relationship between death rates and consumption, a reduction on the overall percentage alcohol by volume (ABV) of alcoholic beverages is another mechanism whereby consumption can be reduced but profitability of the wine industry maintained or indeed increased. Wine at 8.5% ABV must in EU law be taxed at the same level as wine at 14% ABV – a nonsensical system that benefits neither consumer nor industry.

In essence the lesson from Europe is that it is entirely possible to have a healthy population that drinks less overall and a profitable industry sector, but the current structure of EU regulation predisposes neither of these outcomes. A closer examination of patterns of alcohol consumption among high risk groups will reveal further convincing evidence for a strong approach to tackling alcohol-related harm at the European level.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Framework for alcohol policy in the European region. Geneva: WHO; 2006. www.euro.who.int/document/e88335.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson P, Baumberg B. Alcohol and public health in Europe. London: Institute of Alcohol Studies; 2006. http://ec.europa.eu/health-eu/doc/alcoholineu_content_en.pdf. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Directorate General Health and Consumer Protection , European Commission . Special Eurobarometer: health, food and alcohol and safety. Brussels: European Commission; 2003. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/alcohol/documents/ebs_186_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norström T. European comparative alcohol study I. Östersund: Swedish National Institute of Public Health; 2002. www.fhi.se/PageFiles/4400/alcohol-in-postwar-europe-ecas1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karlsson T, Osterberg E. A scale of formal alcohol control policies in 15 European Countries. Nord Stud on Alcohol Drugs. 2001;18:117–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.British Beer and Pub Association . British Beer and Pub Association handbook. London: British Beer and Pub Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.House of Commons Health Committee . Alcohol: first report of session 2009–10. London: Stationary Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Measham F, Brain K. ‘Binge’ drinking, British alcohol policy and the new culture of intoxication. Crime Media Culture. 2005;1:262–83. doi: 10.1177/1741659005057641. doi: 10.1177/1741659005057641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Academy of Medical Sciences . Calling time – the nation's drinking as a major health issue. London: Academy of Medical Sciences; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabinovich L. The affordability of alcoholic beverages in the European Union: understanding the link between alcohol affordability, consumption and harms. Cambridge: RAND Europe; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makela P, Osterberg E. Weakening of one more alcohol control pillar: a review of the effects of the alcohol tax cuts in Finland in 2004. Addiction. 2009;104:554–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02517.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leifman H. Homogenisation in alcohol consumption in the European Union. Nord Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2001;18(Suppl. 1):15–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allamani A, Prina F. Changes in the consumption of alcoholic beverages in Italy between the 1970s and the 2000s? Sheddiing light on an Italian mystery. Contemp Drug Probl. 2007;34:187. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cipriani F, Prina F. The research outcome: summary and conclusions on the reduction in wine consumption in Italy. Contemp Drug Probl. 2007;34:361. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sulkunen . In search of modernity: consumption and consumers of alcohol in France today: an outsider's view. Helsinki: The Social Research Institute of Alcohol Studies; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tusini S. The decrease in alcohol consumption in Italy: sociological interpretations. Contemp Drug Probl. 2007;34:253. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skog OJ. Rationality, irrationality and addiction – notes on Becker and Murphy's theory of addiction. In: Elster J, Skog OJ, editors. Getting hooked: rationality and addiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 173–207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edouard D. ‘Bottles with corks’ – comment at a meeting. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scafato E. Personal communication. 3 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Science Group of the European Alcohol and Health Forum . Does marketing communication impact on the volume and patterns of consumption of alcoholic beverages, especially by young people? – a review of longitudinal studies. Brussels: European Alcohol and Health Forum; 2009. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/alcohol/Forum/docs/science_o01_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]