Abstract

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is among the most common reasons for long-term steroid prescription with great heterogeneity in presentation, response to steroids and disease course. The British Society for Rheumatology and the British Health Professionals in Rheumatology have recently published guidelines on management of PMR. The purpose of this concise guidance is to draw attention to the full guidelines and provide a safe and specific diagnostic process with advice on management and monitoring – specifically targeted at general practitioners, general physicians and rheumatologists.

Key Words: diagnosis, polymyalgia rheumatica, steroid therapy, treatment

Introduction and aims

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is one of the most common inflammatory rheumatic diseases of the elderly and represents one of the frequent indications for long-term corticosteroid therapy in the community. Its management is currently subject to wide variations of clinical practice and it may be managed in primary or secondary care by general practitioners (GPs), rheumatologists and non-rheumatologists.

The diagnosis of PMR can be challenging, as many clinical and laboratory features may also be present in other conditions, including other rheumatological diseases, infection and neoplasm. Also, the response to standardised therapy is heterogeneous, and a significant proportion of patients do not respond completely.

Aims of the guideline

The objective of this concise guidance is to produce a summary of the longer British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology guidelines1 and to provide recommendations in the following areas:

safe and more accurate diagnosis of patients presenting with polymyalgic symptoms

appropriate referral for specialist assessment and management

appropriate corticosteroid dosage regimens

bone protection to reduce the common morbidity of osteoporotic fractures

appropriate follow-up and monitoring procedures.

Information in this concise guidance has been extracted from the full guideline.1 Please refer to the full guidance for details of the methodology. The guidelines were developed using the AGREE criteria and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network guidance was used to grade the recommendations.

Challenges in the diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica

The cardinal features of PMR – proximal pain and stiffness with a raised acute phase response – are familiar to most physicians. However, the diagnostic presentation is varied and this may lead to diagnostic error:

proximal pain and stiffness can occur in many other illnesses

a third of patients have systemic symptoms such as fever, anorexia and weight loss2

a considerable number (15–30%) may have distal musculoskeletal manifestations such as peripheral arthritis, distal swelling with pitting oedema and carpal tunnel syndrome.

PMR is also associated with giant cell arteritis (GCA) in 10% of the cases and up to 50% of cases of GCA may have polymyalgic symptoms at presentation.2 Moreover, an acute phase response can occur in other settings such as other rheumatological conditions, neoplasia and infection.

Many clinicians and two empirically developed sets of diagnostic criteria use a response to corticosteroids as the main defining feature of this condition.3 This, too, may encourage diagnostic error, since corticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatory agents that can mask symptoms from a host of serious conditions ranging from osteoarthritis, rotator cuff problems, rheumatoid arthritis, cancer and infection, especially if used in high doses and for protracted lengths of time.

Studies have shown a revision of the initial diagnosis on follow up in several cases. The list includes infection, neoplasia, inflammatory arthritis and connective tissue diseases.4

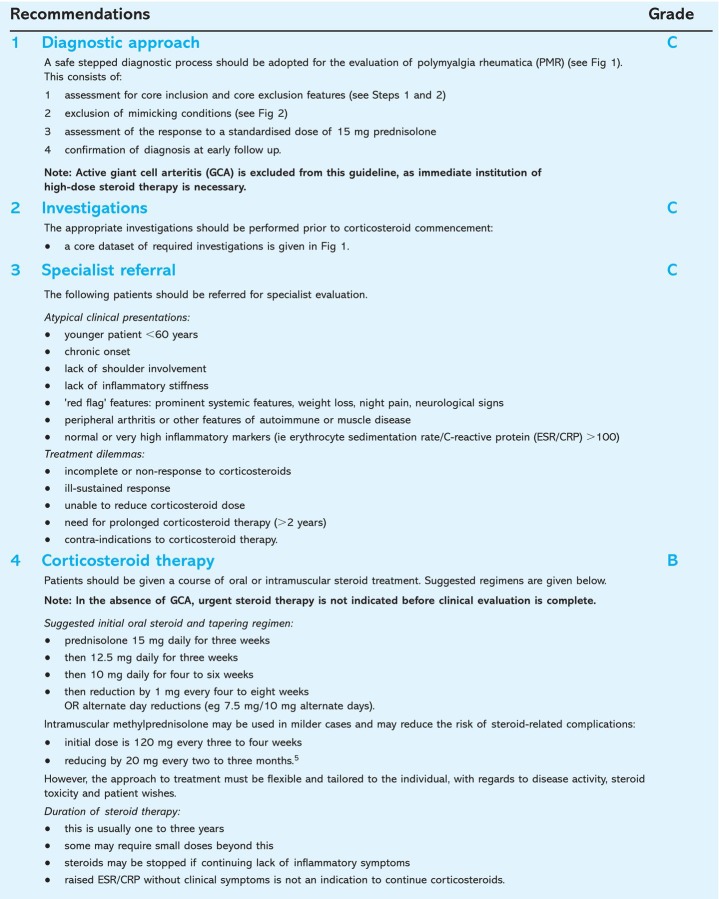

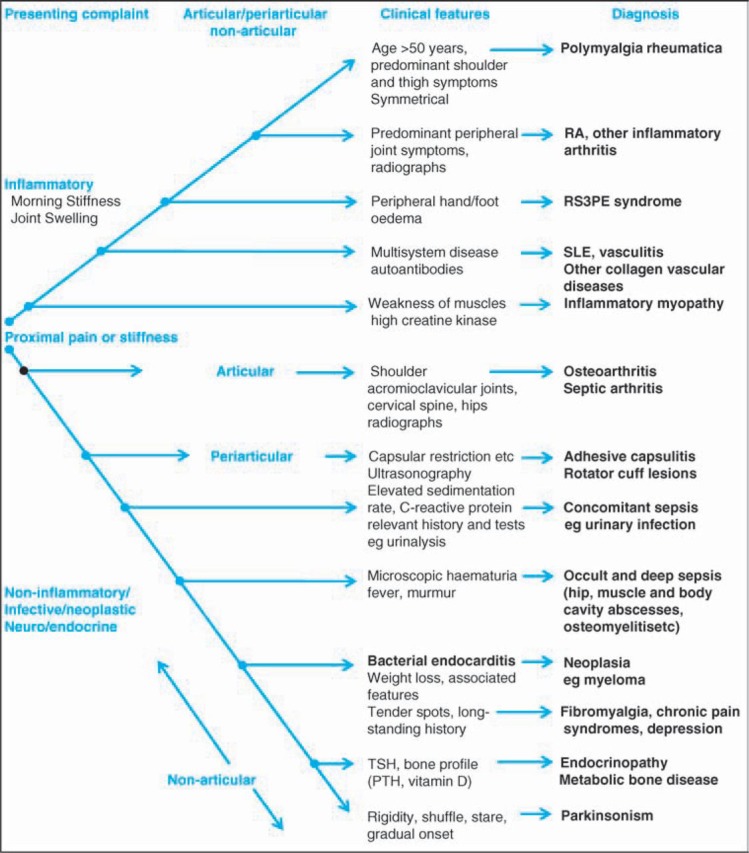

The recommendations.

Definitions and diagnosis

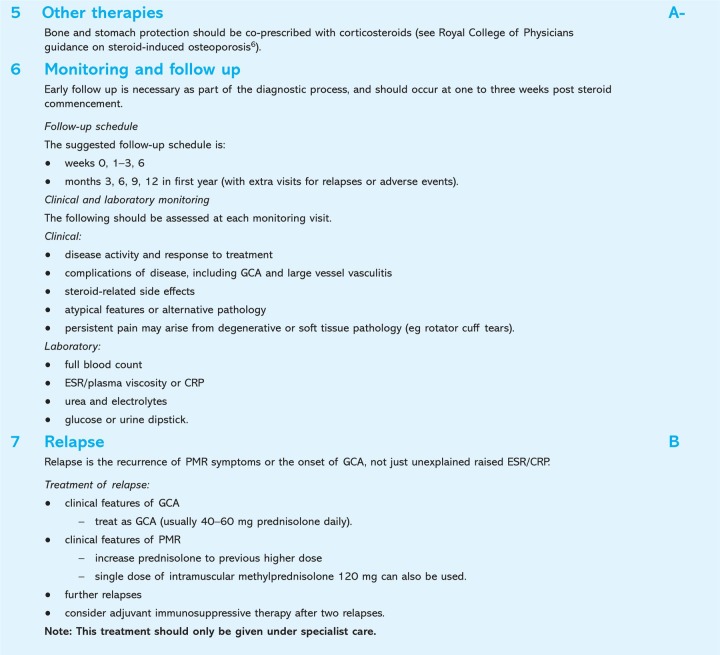

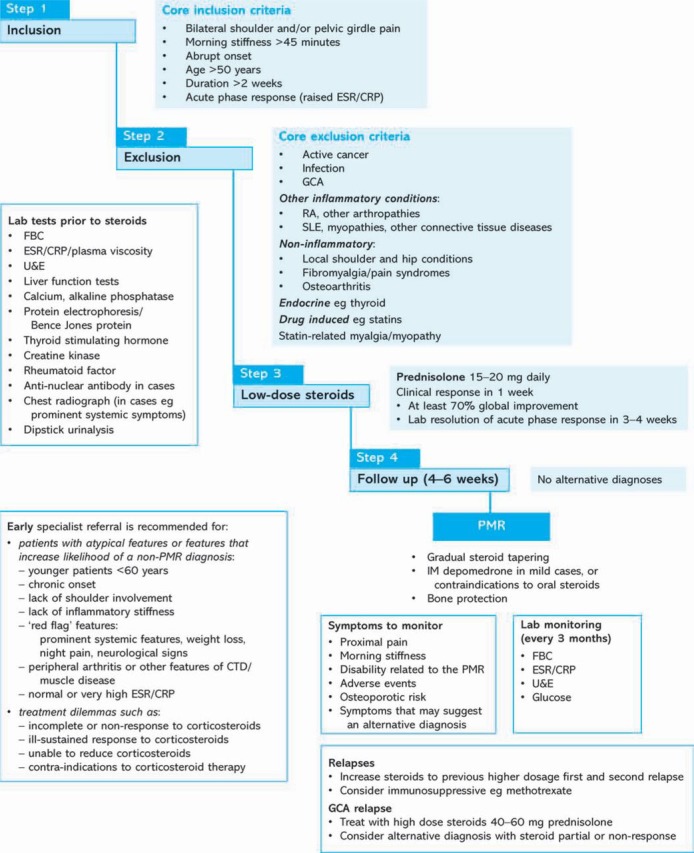

Diagnosis of PMR should start with evaluation for core inclusion and exclusion criteria, the exclusion of mimicking conditions, and a core dataset of laboratory investigations to be performed before treatment. These are outlined in Fig 1. A decision-making approach to proximal pain and stiffness is given in Fig 2.

Fig 1.

A referral pathway for polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) compatible with these guidelines is suggested in the Map of Medicine. CRP = C-reactive protein; CTD = connective tissue disease; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FBC = full blood count; GCA = giant cell arteritis; IM = intramuscular; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus; U&E = urea and electrolytes.

Fig 2.

Recommendation on approach for the evaluation of proximal pain and stiffness. PTH = parathyroid hormone; RA= rheumatoid arthritis; RS3PE = remitting, seronegative symmetrical synovitis with pitting edema; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus; TSH = thyroid stimulating hormone.

This is followed by the assessment of the response to a standardised daily dose of 15 mg prednisolone. In PMR, a clinical response of >70% is expected at one week, with normalisation of laboratory inflammatory markers at four weeks.

An atypical clinical presentation or failure to respond to steroid should prompt the consideration of alternative pathology, and specialist referral. Active GCA is excluded from this guideline, as immediate institution of high-dose steroid therapy is necessary.1 GCA will be the subject of a future set of concise guidance.

Implications for implementation

There are no cost implications for implementation of these guidelines apart from relevant training for GPs who should also have access to the routine investigations outlined and the ability to follow up as suggested.

Further information

Further information on the guidelines, ie references, guideline development process, implications and implementation, is available at Rheumatology online (www.rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org).1

References

- 1.Dasgupta B, Borg FA, Hassan N, et al. BSR and BHPR guidelines for the management of polymyalgia rheumatica. Rheumatology. 2010;49:186–90. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep303a. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep303a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dasgupta B, Kalke S. Polymyalgia rheumatica. In: Isenberg D, Maddison P, Woo P, Glass D, Breedveld F, editors. Oxford textbook of rheumatology, 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 977–82. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dasgupta B, Hutchings A, Matteson EL. Polymyalgia rheumatica: the mess we are in and what we need to do about it. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:518–20. doi: 10.1002/art.22106. doi: 10.1002/art.22106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutchings A, Hollywood J, Lamping D, et al. Clinical outcomes, quality of life and diagnostic uncertainty in the first year in polymyalgia rheumatica. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:803–9. doi: 10.1002/art.22777. doi: 10.1002/art.22777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dasgupta B, Dolan AL, Fernandes L, Panayi G. An initially double-blind controlled 96 week trial of depot methylprednisolone against oral prednisolone in the treatment of polymyalgia rheumatica. Brit J Rheumatol. 1998;37:189–95. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.2.189. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royal College of Physicians . Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: guidelines for prevention and treatment. London: RCP; 2002. [Google Scholar]