Key Points

Patients with chronic heart failure or chronic lung disease understand less about their illness, have fewer choices regarding end-of-life care and more limited access to supportive and palliative care than patients with cancer

Most palliative care problems suffered by these patients should be within the abilities of the usual medical team. All clinicians involved should have good palliative and communication skills

Complex or persistent problems (eg intractable pain, difficult breathlessness) should trigger referral to specialist palliative care services – these are not only for the dying patient

Recognition of dying can be difficult and there is a risk of inappropriate and futile interventions

Breathlessness is a neglected and ‘invisible’ symptom which is a risk factor for emergency hospital admission and caregiver distress

Palliative care for patients with disease other than cancer

Although UK specialist palliative care (SPC) services originated for patients dying from cancer, patients with non-malignant disease also have significant supportive and palliative care needs.1–3 SPC services are now extending care to those with chronic heart failure (CHF) and chronic lung disease (CLD). In spite of the observation, ‘Discomfort was not necessarily greatest in those dying from cancer; patients dying of heart failure, or renal failure, or both, had most physical distress’.4 The medical profession has been quicker to recognise the palliative care needs of patients with cancer and there is still a reluctance to refer patients with these other conditions for palliative care. Despite a prolonged symptom burden, patients with CHF or CLD understand less about their illness, have fewer choices regarding end-of-life care and more limited access to supportive and palliative care than those with cancer.3,5 One explanation suggested for this inequality is the unpredictable illness trajectory of organ failure.6

Chronic lung disease

In CLD, the diagnosis is generally made only when the disease is advanced and patients have lived with problems for many years. Patients often feel ‘undeserving’ as their illness is commonly related to smoking, they seek help very late and often do not understand that the disease is life threatening.7,8

Chronic heart failure

In CHF, decompensations become more frequent, but it is still difficult to anticipate which is the one that will lead to death. This, coupled with a misperception that ‘palliative care’ is relevant only for the dying patient has led to ‘prognostic paralysis’.6 Systematic improvements in the management of CHF (eg National Service Framework, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidance and Quality Outcomes Framework) have improved prognosis, and device therapies, such as implantable cardioverter devices (ICDs), are likely to minimise sudden cardiac death (SCD).9 This may contribute to the difficulty in thinking of CHF as a terminal illness. However, patients who would otherwise have died from SCD will now live to end-stage CHF. Thus, the need for accessible palliative and end-of-life care remains for patients with this highly prevalent disease.

Issues common to chronic heart failure and chronic lung disease

A comprehensive assessment of medical, psychosocial and caregiver issues by the patient's cardiorespiratory team is crucial. Optimal management of underlying pathology, with treatment options tailored to the individual, related to personal choices and disease trajectory, is mandatory. Needs elicited at this assessment (eg symptom control, social support, information about prognosis) can be met by the cardiorespiratory team working in an extended team including primary care and SPC. In this way, an approach of palliative and cardiorespiratory services working together allows access to relevant disease-focused interventions alongside symptom management and support.

SPC services are not only for the dying patient – when referral is often too late – but for patients living with complex or persistent problems. If a problem-based rather than prognosis-based approach is used, referral to services should be appropriate and timely. Otherwise, end-stage disease with its increasing supportive and palliative care needs is often missed despite the presence of markers for poor prognosis. This has a significant impact on the ability to clarify patients' wishes and to plan for care, resulting in avoidable ineffective admissions to acute hospital rather than increased care at home or in hospice.

Common symptoms and their management

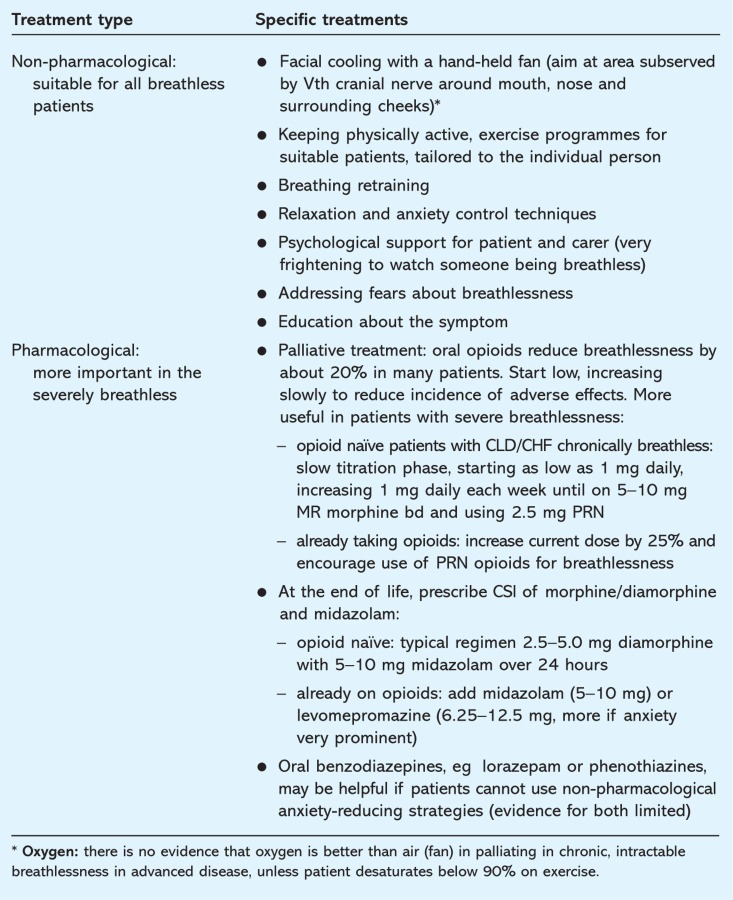

In general, the skills required for symptom management in CHF and CLD are the same as those for patients with malignant disease and are described in more detail elsewhere.10,11 Symptoms such as breathlessness (Table 1)12,13 and fatigue are highly prevalent. Pain, often due to comorbidities, can also be a problem. Depression is a prevalent problem common to both CHF and CLD. It is associated with poorer clinical outcomes such as survival and hospital admission, increased caregiver morbidity and reduction in patient involvement in self-management strategies.

Table 1.

Management of chronic intractable breathlessness (based on Ref 12). CHF = chronic heart failure; CLD = chronic lung disease; CSI = continuous subcutaneous infusion; MR = modified release; PRN = as needed.

Specific issues to consider in patients with chronic heart failure

Heart failure nurses, if available, are well placed to act as key worker, providing a layer of supportive care and optimising cardiac treatment.

Devices

Device therapies may be pertinent for patients with advanced CHF, for example:

cardiac resynchronisation therapy14

left ventricular assist devices

surgical intervention for valvular disease

ablation for atrial fibrillation

referral for transplantation.

These patients are usually highly symptomatic, so a joint approach is often beneficial even if cardiology treatment options are still available. ICDs will need to be reprogrammed to ‘pacing only’ at end-stage to prevent possible repeated shocks that do not prolong quality living.15 Reassurance may be needed that withdrawal of ICD support does not equate to ‘switching off’ the heart and will not lead to immediate death.

Diuretics

As CHF progresses, the patient may become more resistant to diuretics. Continuous infusion of loop diuretics may improve effect.16 The addition of thiazide diuretics (eg bendroflumethiazide or metalozone) may help restore fluid balance, but often at the expense of renal function at this stage. Aldosterone antagonists such as spironolactone should be part of optimal management if tolerated. Continuous subcutaneous infusion of furosemide is an alternative route of administration that could be provided in the community.17,18

Polypharmacy

As CHF progresses, patients may find polypharmacy burdensome and rationalisation is indicated. The mainstays of CHF therapy (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers), beta-blockers and aldosterone antagonists should be continued if blood pressure allows, even if the dose has to be reduced, as these have been shown to help symptom control as well as survival. If there is any doubt about the benefit of medication, advice from the cardiology team should be sought. The decision to continue or stop warfarin can be difficult, not least because patients may be very anxious about the risk of a stroke. However, with worsening disease and liver congestion, international normalised ratio control becomes more difficult and, with deteriorating mobility, the risk of falling brings a risk of head injury and intracerebral bleed.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

There may be unrealistic expectations about the result of attempted cardiopulmonary resuscitation because of previous success in the context of less severe myocardial disease. Although current guidance is clear that there is no obligation to discuss futile interventions, it is good practice to explore patient and carer understanding and expectations of treatment options as part of a broader discussion about stage of illness and aims of management.19 This discussion can be crucial in planning place of care and is an important step in preventing futile hospital admissions.

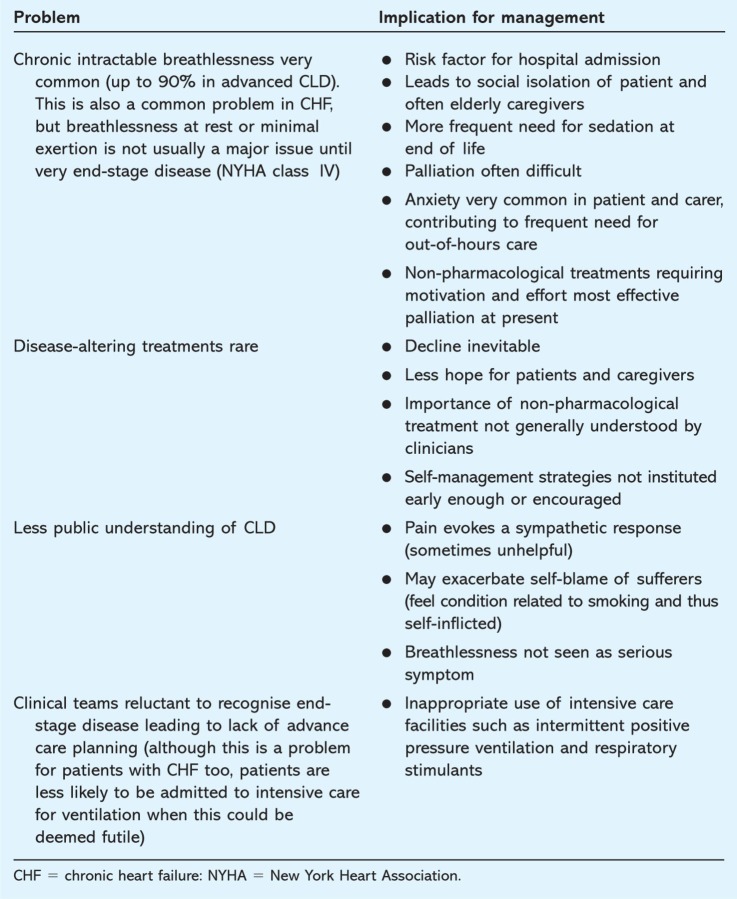

Specific problems for patients with chronic lung disease (Table 2)

Table 2.

Specific problems in patients with chronic lung disease (CLD).

Breathlessness

The key symptom in patients with CLD is breathlessness. This is a risk factor for emergency hospital admission, sedation at the end of life and caregiver distress. In the same way that pain was overlooked in patients with cancer until the mid to late 20th century, breathlessness seems ‘invisible’ or ‘inevitable’. This leads to therapeutic nihilism until patient and family exhaustion and distress lead to hospital admission’. The situation is exacerbated by patients with advanced CLD finding it difficult to go to the clinic or the surgery, so symptoms go unrecognised until a crisis.7 It is important for all clinicians caring for patients with advanced CLD to ask about breathlessness and treat it actively (Table 1).

Breathlessness is a symptom well recognised by SPC services who will see and advise, whether in hospital or the community. They can offer not only specialist symptom control advice but also (variably) symptom control admissions, hospice day therapy, volunteer sitters, bereavement services, hospice at home and carer support. Some may include breathlessness intervention services20 which can work alongside respiratory teams to alleviate this difficult symptom. Education of patient and caregivers about breathlessness management is important (www.cuh.org.uk/breathlessness).

If supportive and palliative services, including social care assistance, are introduced early when breathlessness is only mild and relatively unintrusive, the caregivers, who are often elderly with fewer social supports, may be able to pace themselves better than the all too frequent pattern of stoic acceptance, invisible exhaustion, desperation and unplanned admission to a hospital. It is essential that there are locally agreed systems to identify the best member of the team to coordinate such support.

Recognition of dying can be difficult, and there is a risk of inappropriate and futile intensive care interventions such as ventilation and respiratory stimulants.

Conclusions

All clinicians involved in the care of patients with CHF and CLD should have good generic palliative and communication skills. A full assessment should be carried out and appropriate services involved as an extended team to provide required supportive and palliative care. Although poor prognostic features in individual patients can often be recognised, a problem-based approach will release any ‘prognostic paralysis’. Most palliative care problems suffered by patients with advanced cardiorespiratory disease should be within the abilities of the usual medical team, but complex or persistent problems (eg intractable pain, difficult breathlessness) should trigger referral to SPC. Palliative care teams can ‘dip in and out’ of caring for patients with advanced cardiorespiratory disease as the disease fluctuates and crises are controlled. By working alongside cardiology and respiratory teams, patients can have the best access to care whenever it is required.

References

- 1.Levenson JW, McCarthy EP, Lynn J, Davis RB, Phillips RS. The last six months of life for patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S101–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKinley RK, Stokes T, Exley C, Field D. Care of people dying with malignant and cardiorespiratory disease in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:909–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray SA, Boyd K, Kendall M, et al. Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ. 2002;325:929. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.929. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinton JM. The physical and mental distress of the dying. Q J Med. 1963;32:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers AE, Addington-Hall JM, Abery AJ, et al. Knowledge and communication difficulties for patients with chronic heart failure: qualitative study. BMJ. 2000;321:605–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7261.605. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7261.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ. 2005;330:1007–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Access to services for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the invisibility of breathlessness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:451–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.11.008. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gysels MH, Higginson IJ. Caring for a person in advanced illness and suffering from breathlessness at home: threats and resources. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7:153–62. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509000200. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health . The National Service Framework (NSF) for coronary heart disease (CHD): modern standards and service models. London: DH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson MJ. Management of end stage cardiac failure. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:395–401. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.055723. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.055723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cartwright Y, Booth S. Extending palliative care to patients with respiratory disease. Br J Hosp Med. 2010;71:16–20. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2010.71.1.45967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Booth S. End of life care for the breathless patient. General Practice Update. 2009;2:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rocker G, Horton R, Currow D, et al. Palliation of dyspnoea in advanced COPD: revisiting a role for opioids. Thorax. 2009;64:910–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.116699. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.116699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdulla J, Haarbo J, Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C. Impact of implantable defibrillators and resynchronization therapy on outcome in patients with left ventricular dysfunction – a meta-analysis. Cardiology. 2006;106:249–55. doi: 10.1159/000093234. doi: 10.1159/000093234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein NE, Lampert R, Bradley E, Lynn J, Krumholz HM. Management of implantable cardioverter defibrillators in end-of-life care. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:835–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin SJ, Danziger LH. Continuous infusion of loop diuretics in the critically ill: a review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:1323–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199408000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goenaga MA, Millet M, Sanchez E, et al. Subcutaneous furosemide. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1751. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E172. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verma AK, da Silva JH, Kuhl DR. Diuretic effects of subcutaneous furosemide in human volunteers: a randomized pilot study. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:544–9. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D332. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decisions relating to cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a joint statement from the British Medical Association, the Resuscitation Council (UK) and the Royal College of Nursing. London: BMA; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Booth S, Farquhar M, Gysels M, Bausewein C, Higginson IJ. The impact of a breathlessness intervention service (BIS) on the lives of patients with intractable dyspnea: a qualitative phase 1 study. Palliat Support Care. 2006;4:287–93. doi: 10.1017/S1478951506060366. doi: 10.1017/S1478951506060366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]