Key Points

Palliative care in advanced Parkinson's disease (PD) and multiple sclerosis (MS) recognises the need to move from attempting to control function to affording comfort measures

Admission to an acute hospital can be highly disruptive to the nursing and drug routines for these patients

Advanced disease can lead to cognitive changes in MS, and in PD to dementia and hallucinations, each of which can rob patients of the opportunity to express their wishes and preferences as their disease progresses further

It can be empowering for those patients who still have capacity, sensitively to discuss whether they would wish to receive life-prolonging treatments as their disease progresses, such as intravenous antibiotics, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding tubes and artificial ventilation

The terminal phase of PD and MS usually occurs against a backdrop of more rapid global decline and increasingly severe disability. The terminal event is often an acute episode of sepsis causing death over a few days

Patients with advanced Parkinson's disease (PD) and multiple sclerosis (MS) can present with challenging clinical problems when admitted to acute hospitals. They are susceptible to life-threatening complications, most commonly sepsis, which arise against a backdrop of progressive decline in overall function. Both PD and MS may be complicated by cognitive impairment, swallowing or speech problems and refractory pain syndromes.1,2 Robust evidence supporting treatment decisions in advanced disease is lacking, but recent national guidelines recognise the importance of shifting goals towards a palliative approach as the disease becomes more advanced.3–6

Importance of communication

Prompt and effective discussion between the patient's general practitioner and secondary care clinicians may both prevent inappropriate hospital admissions and achieve treatment decisions in the patient's best interests. Drawing on the strengths of multidisciplinary team working invariably ensures that patients receive better care. The key, however, to optimising care is taking time adequately to hear the patient's wishes before they might lose capacity.

Estimating prognosis

Both in advanced PD and MS it is difficult to anticipate life expectancy, but the rate of overall deterioration is an important indicator of prognosis. Patients are particularly at risk of dying from aspiration pneumonia, urinary tract infections, complications from falls and fractures, and sepsis secondary to pressure ulcers. These are all commoner the more advanced the disease. Even so, some very disabled patients will live for many years while others may succumb quite suddenly from an episode of sepsis or, less commonly, from a pulmonary embolus. The unpredictable disease trajectory makes planning for the terminal event particularly difficult and most patients die in hospital rather than at home.7

Common themes and contrasts in advanced PD and MS

Cognitive/psychiatric

Cognitive changes are common in MS, with loss of verbal fluency, memory problems and difficulty with concentration.8

PD dementia is common, characterised by illusions, visual hallucinations, visuospatial deficits, attentional and dysexecutive deficits.9 PD dementia can respond to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.10 Hallucinations may respond to reduction in PD medication, particularly amantadine, monoamine oxidase type B inhibitors (MAOI-B), cholinergic medication and dopamine agonists.

Depression is common in both illnesses. It may respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). In PD, optimisation of dopaminergic therapy and tricyclic antidepressants have also been shown to have benefit.11 SSRIs should not be co-administered with MAOI-Bs because of the risk of serotonin syndrome.

Bulbar symptoms

Hypophonia in PD and dysarthria in MS can make communication difficult and lead to immense frustration for patients and carers.12

Swallowing problems are associated with aspiration. Early expert assessment by a speech and language therapist is essential. Aspiration may initially be silent without apparent systemic effects, but the situation can change within a few hours as the patient develops systemic signs of sepsis.

Drooling of saliva is more common in PD. It can be managed by ultrasound guided salivary gland botulinum toxin injections, topical atropine 1% drops applied to the tongue or topical hyoscine patches.

Pain

Pain can be a disabling feature of PD2 and may have a variety of causes including central pain and dystonia.

Neuropathic pain in the limbs or face is frequently difficult to treat in MS.13 Amitriptyline and anticonvulsant drugs like gabapentin are often employed. However, both groups of drugs are less well tolerated in MS and there are often unacceptable anticholinergic side effects from tricyclics and sedation and ataxia from anticonvulsants.

Spasticity in MS can cause painful spasms and limb jerking, both of which can be particularly troublesome during the night. Antispasticity drugs have a variable degree of success and tend to cause sedation and ataxia. Limb contractures are a sign of advanced disease.

Pressure ulcers, usually over bony prominences, can be related to loss of mobility and inadequate nutrition.

Decision making

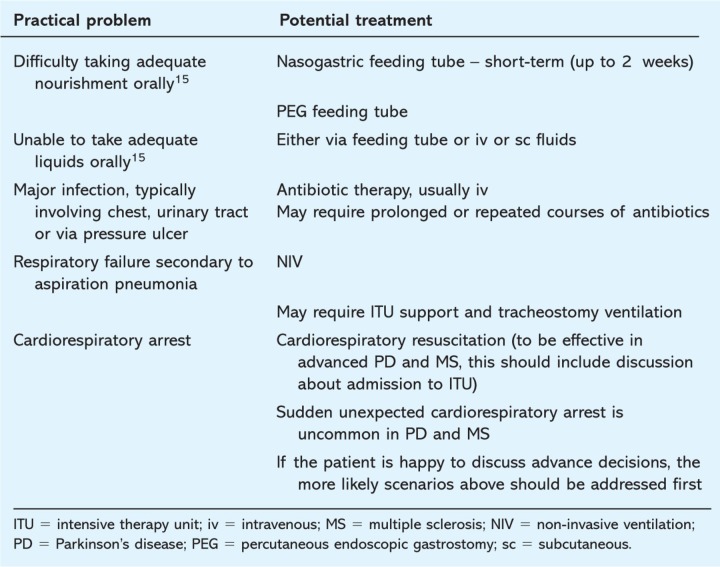

Broaching the topic of life-prolonging treatments is best done when the patient is relatively well and still has capacity for the particular decision. No one should be coerced into advance care planning but some patients will feel more in control having signed an advance decision (refusing specified treatment) (Table 1).14,15

Table 1.

Pertinent topics to consider in advance decisions (refusing treatment) in Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis.

Decision making in the acute situation

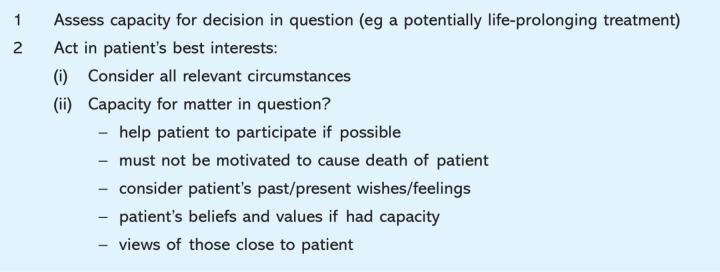

For patients who lack capacity and are acutely unwell, there is a requirement to act in the patient's ‘best interests’ as prescribed by the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Table 2).16 Optimum decision making in advanced PD and MS revolves around ‘trying to get it right’ for the individual patient. As far as possible, this should be what the patient wants or, if they have lost capacity, would have wanted. The patient's previous experience of hospital admissions may influence their preferences.

Table 2.

Making ‘best interests’ decisions, as described in the Mental Capacity Act 2005.16

Withdrawing/withholding treatment and practical symptom management17

As the patient becomes increasingly bedbound, sensitive discussions need to take place with the patient and family about altering the focus of care.5 In both diseases, the aim of treatment shifts from maximising function to minimising suffering and aiming for the patient's comfort and dignity. Common goals are:

freedom from pain

relieving anxiety and agitation (particularly in PD)

- dealing with troublesome symptoms including:

- drooling in PD

- constipation

- bladder spasms

- insomnia.

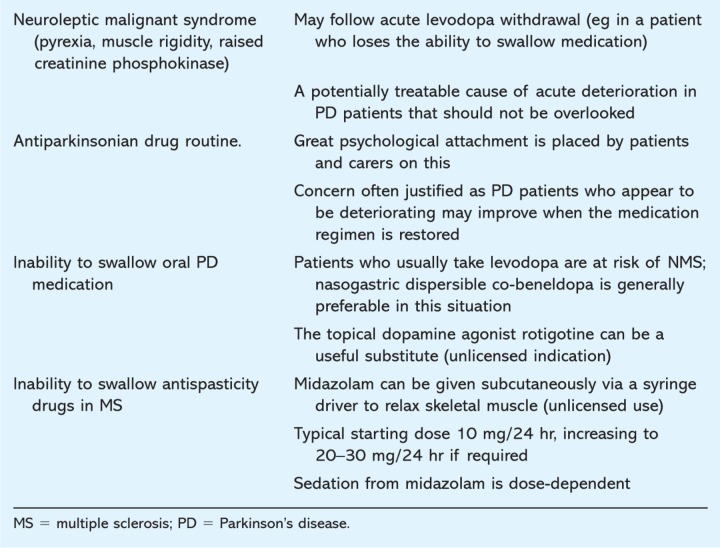

One of the features of advanced PD is the inability to tolerate sufficient dopaminergic medication.18 In both PD and MS it is appropriate to minimise oral medication, particularly statins, antihypertensives and bulk-forming laxatives. Practical suggestions in managing complications for the acute physician are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Tips for the acute medical take.

Managing the terminal phase

When the terminal phase can be anticipated by an acceleration in the patient's global deterioration, a decision may have been taken with the patient and family not to treat further episodes of infection. A careful check for specific symptoms should be sought from the patient directly or from observing the patient for any signs of distress. Close family members will often recognise signs of unspoken distress. The views of experienced clinical staff may determine if the patient is frightened, in pain or has different nursing requirements.

For patients unable to swallow in the terminal stage, medication can be administered subcutaneously as needed or continuously using a syringe driver.19 Medication can be given, if necessary, to relieve specific symptoms as follows:

midazolam for fear or agitation

hyoscine butylbromide for drooling or chesty secretions

morphine for pain

If pain is present, a sufficient dose of morphine should be used to relieve it but without causing undesirable opioid side effects.

References

- 1.Higginson IJ, Hart S, Silber E, Burman R, Edmonds P. Symptom prevalence and severity in people severely affected by multiple sclerosis. J Palliat Care. 2006;22:158–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee MA, Walker RW, Hildreth TJ, Prentice WM. A survey of pain in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. J Pain Sympton Manage. 2006;32:462–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.020. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Management of multiple sclerosis in primary and secondary care, CG8. London: NICE; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Parkinson's disease: diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care, CG35. London: NICE; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Royal College of Physicians, National Council for Palliative Care and British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine. Long-term neurological conditions: management at the interface between neurology, rehabilitation and palliative care. London: RCP; 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health . The National Service Framework for long term conditions. London: DH; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snell K, Pennington S, Lee M, Walker R. The place of death in Parkinson's disease. Age Ageing. 2009;38:617–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp123. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bobholz JA, Rao SM. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: a review of recent developments. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:283–8. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200306000-00006. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200306000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubois B, Burn D, Goetz C, et al. Diagnostic procedures for Parkinson's disease dementia: recommendations from the movement disorder society task force. Move Disord. 2007;22:2314–24. doi: 10.1002/mds.21844. doi: 10.1002/mds.21844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emre M, Aarsland D, Albanese A, et al. Rivastigmine for dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2509–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041470. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menza M, Dobkin RD, Marin H, et al. A controlled trial of antidepressants in patients with Parkinson disease and depression. Neurology. 2009;72:886–92. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000336340.89821.b3. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000336340.89821.b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goy ER, Carter JH, Ganzini L. Parkinson disease at the end of life: caregiver perspectives. Neurology. 2007;69:611–2. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266665.82754.61. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266665.82754.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalia LV, O'Connor PW. Severity of chronic pain and its relationship to quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:322–7. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1168oa. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1168oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. www.adrtnhs.co.uk/index.html.

- 15.Campbell C, Partridge R. Artificial nutrition and hydration. Guidance in end of life care for adults. London: National Council for Palliative Care; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman S. The Mental Capacity Act in practice: guidance for end of life care. London: National Council for Palliative Care; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.British Medical Association . Withholding and withdrawing life-prolonging medical treatment: guidance for decision making. 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas S, MacMahon D. Parkinson's disease, palliative care and older people: Part 1. Nurs Older People. 2004;16:22–6. doi: 10.7748/nop2004.03.16.1.22.c2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.British National Formulary . Prescribing in palliative care. London: BNF; 2009. [Google Scholar]