SYNOPSIS

Shared decision making (SDM) is a core aspect in patient-centered care and helps patients or their surrogate decision-makers formulate more informed decisions with realistic expectations of treatments and outcomes through active participation in the decision. SDM is a collaborative decision-making process between healthcare providers and patients or their surrogates, taking into account the best scientific evidence available, while considering the patient’s values, goals and preferences. Decision aids are tools enabling SDM. High-quality decision aids should follow the 12 quality criteria set by the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration. Few IPDAS-compliant decision aids currently exist for the general ICU, with none currently none for the neuroICU. Our article discusses SDM in general and in the ICU, as well as creation and implementation facilitators and barriers for IPDAS-compliant ICU and neuroICU decision aids.

Keywords: Shared Decision-making, decision aid, patient-centered care, intensive care unit, neurocritical care

INTRODUCTION

Shared decision-making (SDM) has become a “hot ticket item” since the Institute of Medicine’s 2001 report “Crossing the Quality Chasm”1 calling for the transition to “patient-centered care”, and the mandate for SDM by the Affordable Care Act in 20102. It is defined as “a collaborative process involving both the physician and the patient or surrogate working together to make important decisions; it incorporates the beliefs, desires, and goals of patients and their families along with the expertise of the physician, and evidence based medicine to make the best health care decisions for the individual patient”3–5. SDM is commonly employed at the bedside by the use of a “decision aid” (DA). A DA is a tool designed to help patients or their family members decide among treatment options6. They provide objective information about the options, including the option to “do nothing”, and the likely consequences (harms and benefits) of each. DAs often include printed materials, videos, or interactive web programs6.

Over the past 10–20 years, several areas of medicine, including orthopedics7–9, cancer care8–10, and other mainly outpatient oriented fields, have adopted the use of DAs as a routine procedure to enable patient-centered decision-making and support difficult decisions8,9. However, very few DAs exist in critical care11,12, despite the fact that choices in the intensive care unit (ICU), particularly the neuro-ICU, are often difficult and value-laden, and therefore may benefit from SDM13. Recently, a joint policy statement between the American College of Critical Care Medicine and the American Thoracic Society has highlighted the urgent need for SDM in critical care and made recommendations for the application of SDM in the ICU3.

The scope of this current article includes a general introduction to SDM, its history and its existing guidelines for the development of DAs, implementation barriers of SDM, as well as the effects of SDM on patient and surrogate decision-maker outcomes. Examples relating to decisions in the ICU, as well as insights into the recent American College of Critical Care Medicine and the American Thoracic Society SDM recommendations will be provided. Finally, the ongoing SDM research in neurocritical care will be discussed.

History of SDM

The term “patient-centered care” was first coined in 1993. Employing focus groups with recently discharged patients, family members, physicians and non-physician hospital staff, researchers funded by the Picker Foundation and Commonwealth Fund published the “Seven Dimensions of Patient-Centered Care” in the book “Through the Patient’s Eyes”14. “Access to Care” was added as the 8th dimension soon thereafter (Table 1). The 2001 landmark report by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) “Crossing the Quality Chasm”1 urgently called for a change in the U.S. Health Care System towards closure of the quality gap between the current state of a physician-centered system and a more “patient-centered” system concentrating on what really matters to patients (and their families). Patient-centered care was mandated through the Affordable Care Act as a measure of quality care2. Per the IOM, patient-centered care is ‘providing care that is respectful of, and responsive to, individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions’1.

Table 1. The Eight Picker Principles of “Patient-centered care”.

Published in the book “Through the Patient’s Eyes”14, seven principles of “Patient-centered Care” were derived by focus groups with recently discharged patients, family members, physicians and non-physician hospital staff. The 8th principle, “Access to Care” was added soon thereafter.

| Picker Principles of Patient Centered Care |

|---|

| Respect for patients’ values, preferences and expressed needs |

| Coordination and integration of care |

| Information, communication and education |

| Physical comfort |

| Emotional support and alleviation of fear and anxiety |

| Involvement of family and friends |

| Transition and continuity |

| Access to Care |

The term “Shared Decision Making” was first stated in 1982 in a report by the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research on the “Ethical and Legal Implications of Informed Consent in the Patient-Practitioner Relationship”15. However, the concept of SDM remained rather poorly and loosely defined. Fifteen years later, in 1997, the paper by Charles et al. provided key characteristics and measures of SDM, and provided greater conceptual clarity about SDM16. The Federal Program “Healthy People 2020” was launched in 2010 by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and includes supporting SDM between patients and providers in their list of objectives.2,17 The connection between SDM and patient-centered care was crisply summarized in the highly-cited New England Journal of Medicine opinion article in 2012 “Shared Decision-Making – The Pinnacle of Patient-Centered Care”.18

SDM and patient-centered care

Essential elements of SDM

One of the most important attributes of patient-centered care is the active engagement of the patient and a collateral decision-making process to reach the best decision for an individual patient. To achieve this, SDM is employed. SDM involves a patient, or a surrogate decision-maker in cases where a patient lacks decision-making capacity, and a healthcare provider. The exchange of information takes place between both parties to describe the decision at hand, discuss available options (including the option of no treatment), their risks and benefits along with evidence based medicine, pro’s and con’s of each option, and most importantly the patient’s values and preferences. Figure 1 shows the essential elements and steps of SDM. As a result, the patient (or his/her surrogate) and the healthcare provider both have an improved understanding of the factors relevant to the patient and shares equal responsibility on the agreed treatment course.

Figure 1. Step-wise process of shared decision-making.

We show the core aspects to initiate, streamline, and establish a proper SDM dialogue.

Preferences and values in SDM

One of the important goals of SDM is to elicit patient values and preferences during the patient-physician conversation1,3,8,18. A patient’s goal might not always align with that of the physician. Several research studies have shown that physicians do not routinely elicit patient or surrogate preferences, especially early on in the communication process8, 19. Furthermore, patient and physician values and preferences may differ tremendously. For example, according to qualitative research in patients with multiple sclerosis, patients tend to focus more on the ability to walk and self-groom, while physicians would divert most of their attention on ‘choosing the right medication to minimize progression’19.

The essential elements of SDM have been summarized by the 5-step SHARE Approach published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)5 (Table 2). On the AHRQ SHARE-Approach website, one finds information on the SHARE Approach Workshop curriculum developed by AHRQ to support the training of health care professionals on how to engage patients in their health care decision-making5. This includes the SHARE Approach tools, a collection of reference guides, posters, slides, videos, fact sheets, and other resources, all designed to support implementation of the SHARE Approach.

Table 2.

Five steps of ‘SHARE Approach’ by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)5

| The SHARE Approach |

|---|

| 1. Seek your patient’s participation |

| 2. Help your patient explore and compare treatment options |

| 3. Assess your patient’s values and preferences |

| 4. Reach a decision with your patient |

| 5. Evaluate your patient’s decision |

Development process of DAs

As of 2014, 115 randomized-controlled trials testing DAs for various decisions in a variety of conditions involving 34,444 participants have been published and summarized in a Cochrane review8. Many more DAs not yet tested in randomized controlled trials exist.

Need for DA quality criteria – the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS)

With hundreds of DAs available and many more in development around the world, it was impossible to judge and compare the quality of these DAs. Established in 2003, the IPDAS collaboration included researchers, practitioners, patients, and policy makers and created a set of guidelines for the development and implementation of DAs19. The goal of these standards was to improve the content, development, implementation, and evaluation of DAs. The twelve quality criteria in the domains ‘content’, ‘development process’ and ‘effectiveness’ are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. IPDAS criteria.

The International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) include 12 quality criteria in the domains ‘content’, ‘development process’ and ‘effectiveness’ with the goal to improve the quality of DAs19.

| The 12 dimensions of the IPDAS checklist for the development of decision aids |

|---|

| 1) Using a Systematic Development Process |

| 2) Providing Information about Options |

| 3) Presenting Probabilities |

| 4) Clarifying and Expressing Values |

| 5) Using Personal Stories |

| 6) Guiding/Coaching In Deliberation and Communication |

| 7) Disclosing Conflicts Of Interest |

| 8) Delivering Decision Aids on the Internet |

| 9) Balancing the Presentation of Information and Options |

| 10) Addressing Health Literacy |

| 11) Basing Information On Comprehensive, Critically Appraised, And Up-To-Date Syntheses Of the Scientific Evidence |

| 12) Establishing the Effectiveness |

Development tool kits and existing IPDAS-compliant DAs

The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute provides a comprehensive DA development tool kit as a free resource20: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/resources.html. Also hosted here is an online, self-guided tutorial that takes one through the Ottawa patient DA development process9. The largest A-Z online inventory of existing DAs meeting IPDAS criteria can be found at https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZinvent.php. Here one can search by decision or disease process. Each DA displays a graphical presentation of whether each of the 12 IPDAS criteria are met.

Implementation of DAs

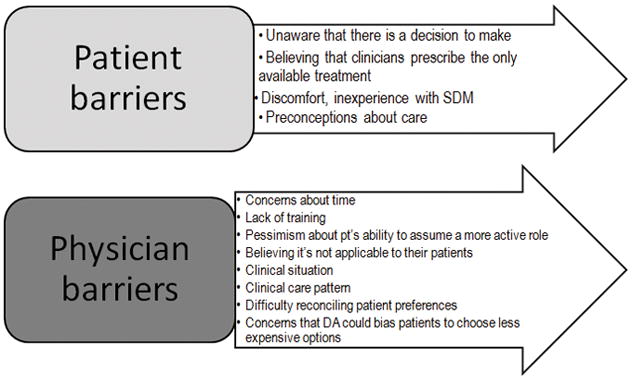

While the development of DAs has significantly increased since the IOM report, SDM implementation has proven to be much more difficult. Many important patient and physician barriers have been identified (Figure 2). Patient barriers include the unawareness for a need of decision to be made, the belief that clinicians prescribe the only available treatment, discomfort and inexperience with SDM, and preconceptions about care and certain options8. Physician barriers include the concern for time, lack of training, pessimism about the patient’s ability to assume a more active role, certain clinical situations, difficulty with reconciling patient preferences, and concerns that DA’s could bias patients to choose less expensive options8.

Figure 2. Barriers of SDM implementation.

Perceived and observable barriers to SDM.

To facilitate overcoming the SDM implementation gap and improve the implementation and acceptability of DAs in clinical practice, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) has focused its grant mechanisms on comparative effectiveness of the use of existing DAs compared to standard care21.

Effects of DAs on decisions and decision-making

Several outcomes of decision-making have been examined to understand the effects of DAs, and the effects are variable on specific outcomes (Figure 3)6,8. A regularly updated Cochrane review summarizes all existing DAs and their effect on specific decision- and treatment-related outcomes8. DAs been shown to improve knowledge of treatment choices, existing options and outcomes, and have led to a more realistic expectation of outcomes. By ‘helping the undecided to decide’, they have helped match values to the patients’ choices, and thereby reduce decisional conflict and decision passivity. However, DAs do not improve adherence to medications, and their impact on treatment choices is modest and variable. In those surgeries for which DAs have been created and studied, they have been shown to reduce major elective surgeries, but not minor elective surgeries8.

Figure 3. Effects of a decision aid on decision-making.

Shown is a summary of the positive, negative and neutral effects of DAs in decision-making6,8

SDM in the ICU – existing DAs and ongoing research

In the ICU, patients are typically too ill to engage in their own decision-making, thereby requiring surrogates (often family members or next-of-kin) to make decisions on their behalf. The most common situation in the ICU for which surrogates are approached for decision-making are incapacitated patients near the end of life, or neurologically severely injured patients for whom the outlook is unknown or perceived to be “poor”. The need for SDM has been underlined by studies undertaken in medical and surgical ICUs. A mixed-methods study of 71 audio-recorded physician-surrogate family meetings discussing life-sustaining treatment decisions for an incapacitated patient near the end of life have shown that in ~1/3 of conferences no discussions about the patient’s previously expressed preferences or values were held. In the same study, there was no conversation about the patient’s values regarding autonomy and independence, emotional well-being and relationships, physical function, or cognitive function in close to 90% of conferences222. No such studies have been undertaken in the NeuroICU specifically. However, we know from our own qualitative study23 in 20 physicians caring for critically-ill traumatic brain injury patients (half neuro intensivists, the other half neurosurgeons or trauma surgeons) that the majority of physicians believe that they already engage in SDM. However, when asked how these physicians communicate prognosis and discuss the decision surrounding goals-of-care, none have a clear understanding of the definition of SDM3–5. This finding is underlined by a previous multi-center qualitative study analyzing audiotaped physician-family conferences discussing end-of-life decisions in medical and surgical ICUs24. It revealed that only 2% of decisions met all 10 pre-defined criteria for SDM. The least frequently addressed elements were the family’s role in the decisions making and an assessment of the family’s understanding of the decision. In the same study, higher levels of SDM were associated with greater family satisfaction with communication24.

The recent policy statement of the American College of Critical Care Medicine and the American Thoracic Society3 have recommended when and how SDM should be employed in the ICU. This policy statement also identified the range of ethically acceptable decision-making models, and presented important communication skills for all ICU providers to achieve a basic level of SDM in the ICU.

Few DAs exist for critically-ill patients. Cox et al. created a DA for patients on prolonged mechanical ventilation to aid goals-of-care decision-making by surrogates, including tracheostomy and feeding tube placement12. A PDF version is available for print as an online supplement to the manuscript12. The development of this DA was guided by the IPDAS criteria and then tested in a prospective multicenter before/after study comprised of 53 surrogate decision-makers and 58 medical ICU physicians. Primary outcomes of this study were discordance of expected patient survival, quality of communication and dialogue, and comprehension of medical information. All three outcomes showed significant improvement after the implementation of the DA (all p<0.05); in addition, use of the DA achieved an advantageous financial impact, with >$50,000 savings (p=0.04). Mortality was not significantly different (p=0.95). Almost all of the surrogates (94%) and all of the physicians agreed to the usefulness of using the DA in this setting. Subsequently, this DA has been converted to a web-based DA, which is, however, not publicly available253.

A different, publicly available DA for the goals-of-care decision for critically-ill patients admitted to the ICU was developed by the Ottawa Patient DA Research Group24. This DA is particularly aimed at surrogate decision-makers to help plan the end-of-life and comfort care options26. Per the IPDAS criteria, this DA met 10/10 of the content criteria, and 9/9 development process criteria, but its effectiveness has not yet been evaluated.

Currently, no neuroICU-specific DAs exist. There is an abundance of literature suggesting that patients with hemorrhagic stroke or severe traumatic brain injury may be subject to early, grave, and biased prognostications, sometimes leading to self-fulfilling prophecies27–31. Furthermore, it is likely that the prognostic discordance between surrogates and physicians observed in a mixed ICU population32 is at least as prevalent in the neuroICU owing to the sudden nature of the patient’s grave illness. Physician prognostic bias as well as surrogate’s misunderstanding about prognosis may be mitigated by the use of a SDM intervention, such as a disease-specific DA in the neuroICU3,6,13. With funding from the National Institutes of Health, research is currently underway to create a neuroICU-specific DA for goals-of-care decisions in critically-ill traumatic brain injury patients in order to fill this unmet need13. The ultimate goal is to create further DAs for other decisions in the neuroICU.

In summary, this article raises awareness of SDM in general, including the urgent need for its implementation in the ICU, highlights the IPDAS criteria to ensure the creation of IPDAS-compliant DAs, and has lists important DA implementation barriers. In the meantime, until neuroICU disease-specific DAs have been tested in clinical trials, two basic DAs aimed at goals-of-care decisions in patients without neurological injury may still be worth using in the neuroICU12,26.

Keypoints.

Shared decision-making (SDM), an essential part of patient-centered care, is a collaborative process in which healthcare providers, patients or surrogate decision-makers make medical decisions together, taking into account the best scientific evidence available, while considering the patient’s values, goals and preferences.

SDM has been shown to reduce decisional conflict and passivity, and lead to more realistic expectations of treatments and outcomes.

Decision aids are SDM tools; high-quality decision aids should follow the 12 quality criteria set by the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration.

Few decision aids exist currently in general ICUs; none IPDAS-compliant decision aids exist for the neuroICU.

Research is currently underway to help develop IPDAS-compliant decision aids for the neuroICU.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: Dr. Muehlschlegel is funded by NIH/NICHD grant 5K23HD080971.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine; Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, H.R. 3590. Public Law 111–148. 111th Cong ed2010.

- 3.Kon AA, Davidson JE, Morrison W, et al. Shared Decision Making in ICUs: An American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society Policy Statement. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:188–201. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Informed Medical Decisions Foundation. What is Shared Decision-Making? 2016 at http://www.informedmedicaldecisions.org/shareddecisionmaking.aspx.

- 5.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed 11/28/2016];The SHARE approach: 5 Essential Steps to Shared Decision-Making. 2014 at http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/index.html.

- 6.Col N. Communicating Risks and Benefits: An Evidence-Based User’s Guide (FDA) Chapter 17. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration (FDA), US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. Shared Decision Making. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slover J, Shue J, Koenig K. Shared decision-making in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:1046–53. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2156-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otttawa Hospital Research Institute. [Accessed 11/28/2016];A-Z Decision Aid Inventory. 2015 at https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZlist.html.

- 10.Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Arora NK, et al. Association of Actual and Preferred Decision Roles With Patient-Reported Quality of Care: Shared Decision Making in Cancer Care. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:50–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2014.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Understanding the Options: Planning care for critically ill patients in the Intensive Care Unit. The Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making. 2009 at http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/das/Critically_Ill_Decision_Support.pdf.

- 12.Cox CE, Lewis CL, Hanson LC, et al. Development and pilot testing of a decision aid for surrogates of patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2327–34. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182536a63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muehlschlegel S, Shutter L, Col N, Goldberg R. Decision Aids and Shared Decision-Making in Neurocritical Care: An Unmet Need in Our NeuroICUs. Neurocrit Care. 2015;23:127–30. doi: 10.1007/s12028-014-0097-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J, Delbanco TL. Through the Patient’s Eyes: Understanding and Promoting Patient-Centered Care. 1. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Making Health Care Decisions: the Ethical and Legal Implications of Informed Consent in the Patient-Practitioner Relationship. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango) Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681–92. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed 11/28/2016];Healthy People 2020 - Overview of Health Communication and Health Information Technology Priorities. 2010 at https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/health-communication-and-health-information-technology.

- 18.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:780–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. [Accessed 11/28/2016];Decision Aid Development Toolkit. at https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/resources.html.

- 21. [Accessed 11/28/2016];PCORI Communication and Dissemination Research. at http://www.pcori.org/about-us/our-programs/communication-and-dissemination-research.

- 22.Scheunemann LP, Cunningham TV, Arnold RM, Buddadhumaruk P, White DB. How clinicians discuss critically ill patients’ preferences and values with surrogates: an empirical analysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:757–64. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quinn T, Moskowitz J, Shutter L, et al. Contrasting Preferences on the Communication of Prognosis between Family Members and Physicians during Goals-of-Care Decisions in Critically-Ill TBI Patients - Results from a Multi-Center Qualitative Study. Neurocrit Care. 2016;25:S62. [Google Scholar]

- 24.White DB, Braddock CH, 3rd, Bereknyei S, Curtis JR. Toward shared decision making at the end of life in intensive care units: opportunities for improvement. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:461–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox CE, Wysham NG, Walton B, et al. Development and usability testing of a Web-based decision aid for families of patients receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5:6. doi: 10.1186/s13613-015-0045-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. [Accessed 12/5/2016];Understanding the Options: Planning care for critically ill patients in the Intensive Care Unit Ottawa Patient Decision Aid Research Group. 2015 at https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/das/Critically_Ill_Decision_Support.pdf.

- 27.Becker KJ, Baxter AB, Cohen WA, et al. Withdrawal of support in intracerebral hemorrhage may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Neurology. 2001;56:766–72. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.6.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemphill JC, 3rd, White DB. Clinical nihilism in neuroemergencies. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2009;27:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turgeon AF, Lauzier F, Simard JF, et al. Mortality associated with withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy for patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a Canadian multicentre cohort study. CMAJ. 2011;183:1581–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turgeon AF, Lauzier F, Burns KE, et al. Determination of neurologic prognosis and clinical decision making in adult patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a survey of Canadian intensivists, neurosurgeons, and neurologists. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1086–93. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318275d046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Izzy S, Compton R, Carandang R, Hall W, Muehlschlegel S. Self-fulfilling prophecies through withdrawal of care: do they exist in traumatic brain injury, too? Neurocrit Care. 2013;19:347–63. doi: 10.1007/s12028-013-9925-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White DB, Ernecoff N, Buddadhumaruk P, et al. Prevalence of and Factors Related to Discordance About Prognosis Between Physicians and Surrogate Decision Makers of Critically Ill Patients. JAMA. 2016;315:2086–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]