Key points

Palliative care often runs in parallel with active disease-modifying treatment

In chronic lung disease, there is typically a prolonged phase of symptom control and support, and a short dying phase

Being on a lung transplant waiting list should not be a barrier to palliative care

Opiate and benzodiazepine drugs can be helpful for breathlessness and associated anxiety

Oxygen is helpful in relieving breathlessness only in patients with hypoxia

Palliative care of chronic lung disease is particularly complex, but considerable progress has been made in supporting these patients. A flexible approach is needed to meet the individual patient's needs. Integration of palliative care professionals into the respiratory multi-disciplinary team is often the most appropriate way of achieving this, such that disease-modifying care, palliative care and anticipatory planning can run in parallel. Good quality care must be achieved in a variety of settings including the patient's home, care homes, clinics, emergency departments, specialist respiratory wards and intensive care units.

Palliative care is a crucial component of a comprehensive service for patients with chronic progressive lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), interstitial lung disease (ILD) and cystic fibrosis (CF).1–5 There are considerable difficulties in meeting the needs of these patients, many are not currently referred for specialist palliative care and the best model of service provision has not been clearly established.6–8 One of the main barriers is a mistaken concept that palliative care is a separate stage at the end of life when all disease–modifying options have been exhausted. Modern palliative care, however, applies at a much earlier stage in the disease process, as an integral part of standard care, and is based upon needs rather than prognosis. National initiatives have focused attention on the provision of high-quality palliative care.9

Disease trajectories and models of care

In many chronic progressive lung diseases, the clinical course is prolonged, variable and unpredictable.7,8 It is sometimes necessary for the patient and the clinical team to accept and adapt to uncertainty.

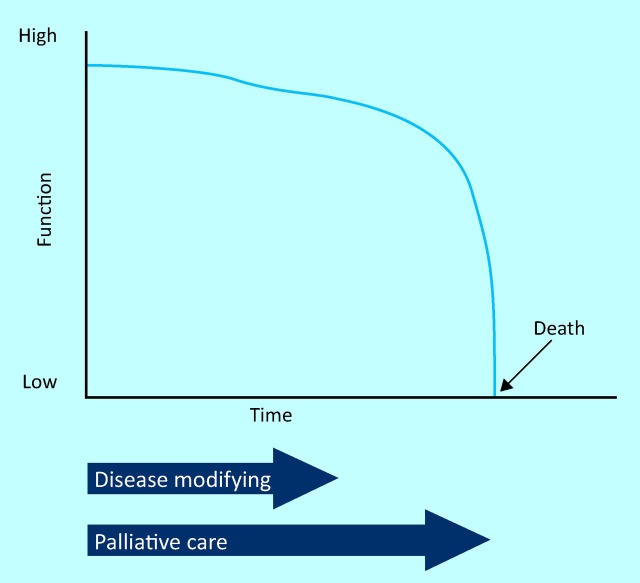

The cancer trajectory

Traditional models of palliative care have often been based on the cancer trajectory (Fig 1). A patient with lung cancer, for example, may have an initial phase of disease-modifying treatments, such as -chemotherapy and radiotherapy, followed by a phase of progression of the cancer with declining health, evolving into end-of-life care. There is sometimes a reasonably clear break between disease-modifying treatments and palliative care, typically with a transfer of care from oncology to palliative care teams. Now, however, there is increasing evidence that early palliative care from diagnosis improves outcomes for patients with lung cancer, such that palliative care and active anti-cancer treatments often run in parallel.10

Fig 1.

The cancer trajectory. The traditional cancer trajectory used to be based upon an initial phase of disease-modifying treatments followed by -palliative care, with transfer of care from oncology to palliative care teams. Now, early palliative care improves outcomes for patients with lung cancer such that palliative care and disease-modifying treatments often run in -parallel.10

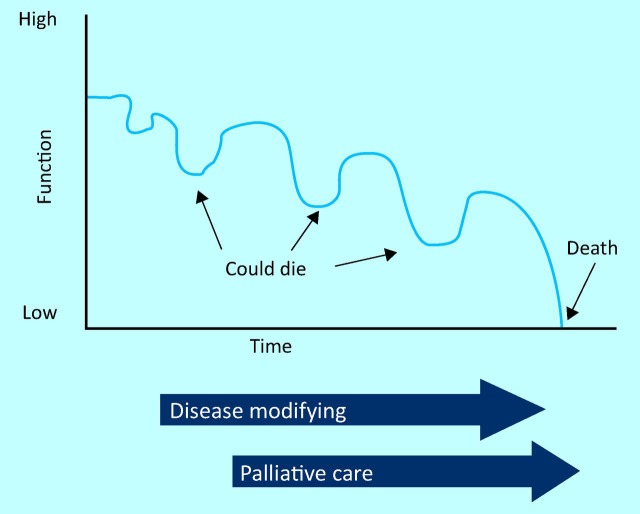

The chronic lung disease trajectory

Chronic lung diseases are often characterized by recurrent episodes of exacerbations and recovery, with progression over many years (Fig 2). Exacerbations of COPD are treated by bronchodilators, antibiotics, corticosteroids, oxygen and non-invasive ventilation. Exacerbations of CF are treated by antibiotics, mucolytic drugs and sputum clearance techniques. Complications, such as pneumothorax or haemoptysis, may occur in advanced disease and require emergency interventions. Such treatments may well reverse the underlying disease process and are also the most effective method of relieving symptoms. The patient may be critically ill but recover from all exacerbations except for the last one.

Fig 2.

The chronic lung disease trajectory. The chronic lung disease trajectory is characterised by exacerbations and recovery such that disease-modifying treatments and palliative care must run in parallel.

The final illness typically starts as a further exacerbation. The patient is very breathless and anxious, and the family is very distressed. The patient is admitted to hospital with the expectation that there will again be a response to treatment. It is only after a few days that it becomes clear that the patient is failing to improve and is now dying. The dying phase is then often short and many patients opt to stay in hospital rather than to return home or transfer to a hospice.5 This choice reflects the fact that it can be difficult for community teams to provide the same level of security, symptom-relief and support that can be provided in hospital. Furthermore, many of these patients will have established relationships with their multidisciplinary team, who may also be in the best position to provide end-of-life care. For patients with specialist diseases, such as CF, admission to hospital is usually directly to their specialist team. It is then possible to bring control and comfort to a situation of crisis, by rapidly diagnosing the nature of the problem, deciding what specific treatments are appropriate and giving -symptom-relieving medications. It is more difficult to achieve this patient-centred care for the large numbers of patients with COPD for example.2 Ideally, a patient would be admitted directly to a team that knows them well. Where this is not feasible, detailed documentation of their diagnosis, potential treatments and specific advanced directives needs to be available to emergency teams, both in hospital and in the community. For patients with chronic lung disease, this information will often not involve a simplistic categorisation as to whether the patient is in ‘active treatment’ or ‘palliative only’. Instead, it will say that the patient has advanced disease and that standard treatments have often resulted in recovery and are also the best way of relieving symptoms, but that if the patient fails to respond, it would be appropriate to switch the focus to the relief of symptoms and to ensuring that a peaceful, dignified, natural death is achieved. For this disease trajectory, it is clear that specific disease-modifying treatments and palliative care must run in parallel. These concepts are typically expressed as ‘a ceiling of treatment’. Discussion of anticipatory planning and the patient's wishes in chronic lung disease usually results in an acknowledgement of advanced progressive disease, a risk of dying and an outline of potential treatments, but also in a recognition of a limit to what can be achieved. Many patients who might express a wish to be at home if dying opt for admission to hospital in the distress of a crisis, and decisions about best place of care need to be flexible and able to adapt to circumstances.

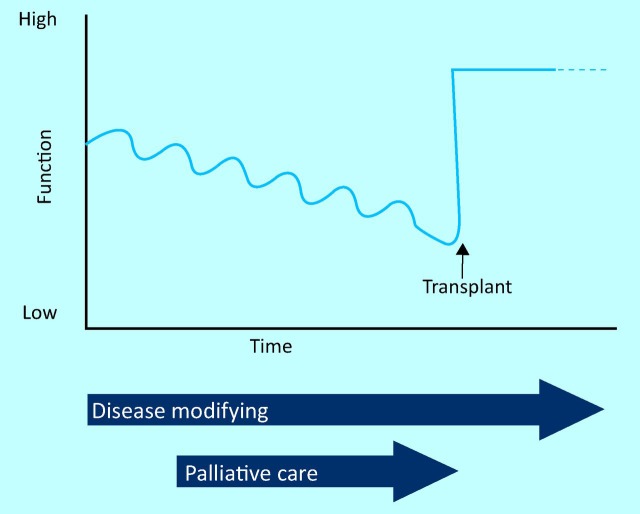

The transplant trajectory

Some patients who die from progressive lung disease are on a lung transplant waiting list. This is common for patients with CF but may also be the case for some patients with ILD and some less common lung diseases. The patient is seriously ill with a high level of symptoms, and may die, but is hoping for a rescue transplant that dramatically alters the disease trajectory (Fig 3).4,5 If traditional models of palliative care are applied, being on a lung transplant waiting list may act as a barrier to them receiving specialist palliative care for symptom control and support.

Fig 3.

The lung transplant trajectory. In the transplant trajectory, the -patient is seriously ill and may die, but is hoping for a rescue transplant. -Palliative care is part of the support and symptom control offered when the patient is critically ill, but may not need to continue after transplantation.

Integrated palliative care

For most patients with chronic lung disease, the division of care into ‘active’ or ‘palliative’ is inappropriate as disease-modifying treatments and palliative care must run in parallel.5–8 In many cases, these patients are treated by multi-disciplinary teams of doctors, nurses, physiotherapists and other professionals. It is often most appropriate for palliative care teams to be integrated into the multidisciplinary team, working in parallel with the chest team. In an integrated model of care provision, palliative care principles can be applied at an earlier stage of the disease, and preparation and planning can occur for the end-of-life phase. Much of the palliative supportive care may be given by the respiratory team as general palliative care, but the palliative care team can provide advice and support, and can see patients with specialist needs.

There may be key points at which to consider a formal palliative assessment. In CF, for example, such an assessment might be appropriate when the role of lung transplantation is being considered. For COPD patients, it may be appropriate to make a palliative assessment when the patient has had an episode of non-invasive ventilation for respiratory failure, or for ILD patients, when there is progressive decline in lung function.

Palliation of symptoms

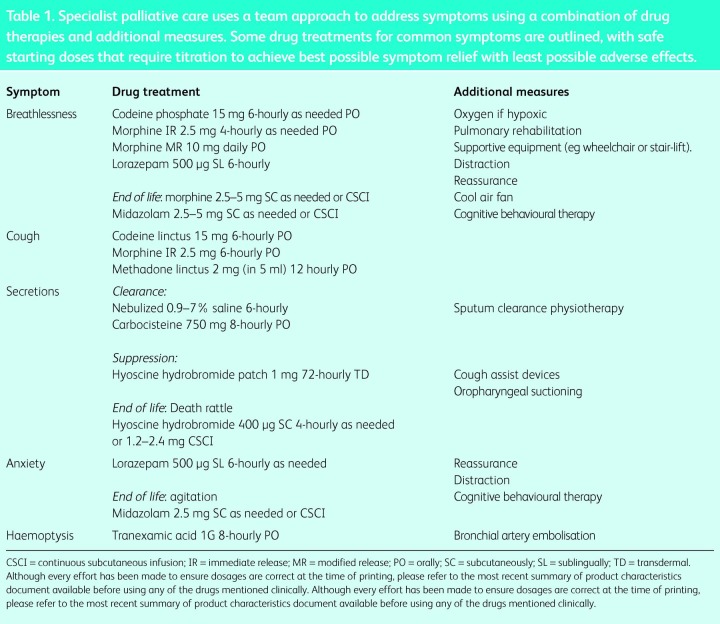

At a time of disease progression, the medical team if often focused on a decline in lung function and oxygenation, prompting intensification of treatments. A specialist palliative care consultation can give some control to patients and clinicians by focusing on what can be done to improve the situation while acknowledging what cannot be achieved. It is helpful to have a specific assessment of physical symptoms such as breathlessness, cough, pain, fatigue and secretions, the emotional impact of these symptoms, coping strategies, and fears and concerns for the future (Table 1). This can lead to advance care planning that anticipates and provides for the management of future problems. Key elements of palliative care include the relief of symptoms and distress, a team approach in addressing the needs of patients and their families, the enhancement of life, the -mitigation of suffering and the recognition of dying as a normal process bringing life to a natural end.

Table 1.

Specialist palliative care uses a team approach to address symptoms using a combination of drug therapies and additional measures. Some drug treatments for common symptoms are outlined, with safe starting doses that require titration to achieve best possible symptom relief with least possible adverse effects.

Breathlessness is a dominant symptom that can be treated by a combination of drug therapies, such as opiates and benzodiazepines, and non-drug therapies, such as nursing in an upright posture, use of a cool air fan, breathing control measures and reassurance.11–15 Breathlessness is frequently linked to anxiety in a vicious circle and cognitive behavioural therapy techniques can be useful.16 Oxygen is indicated for hypoxia, but is not of benefit to patients who are breathless without hypoxia.17 Optimal disease-modifying measures and pulmonary rehabilitation may improve breathlessness but reduced exercise capacity with associated breathlessness is often an inherent feature of lung disease, and patients are likely to need additional -support in coping with daily activities. A non-productive cough may be helped by opiates.18,19 Patients with chronic suppurative lung diseases, such as CF, bronchiectasis and COPD, may have difficulty expectorating sputum and have a particular fear of ‘choking to death’. Mucolytic drugs (eg hypertonic saline or carbocisteine) can be combined with sputum-clearing physiotherapy techniques. Hyoscine is useful in drying secretions at the end of life.20

References

- 1.Partridge MR, Khatri A, Sutton L, et al. Palliative care services for those with chronic lung disease. Chron Respir Dis. 2009;6:13–7. doi: 10.1177/1479972308100538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gore JM, Brophy CJ, Greenstone MA. How well do we care for patients with end stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? A comparison of palliative care and quality of life in COPD and lung cancer. Thorax. 2000;55:1000–6. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.12.1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bajwah S, Ross JR, Peacock JL, et al. Interventions to improve symptoms and quality of life of patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a -systematic review of the literature. Thorax. 2013;68:867–79. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sands D, Repetto T, Dupont LJ, et al. End of life care for patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cystic Fibrosis. 2011;10:S37–S44. doi: 10.1016/S1569-1993(11)60007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourke SJ, Doe SJ, Gascoigne AD, et al. An integrated model of -provision of palliative care to patients with cystic fibrosis. Palliat Med. 2009;23:512–7. doi: 10.1177/0269216309106312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanken P, Terry PB, DeLisser HM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with -respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:912–27. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourke SJ, Peel ET. Integrated palliative care of respiratory disease. London: Springer-Verlag; 2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boland J, Martin J, Wells AU, Ross JR. Palliative care for people with non-malignant lung disease: summary of current evidence and future direction. Palliat Med. 2013;27:811–16. doi: 10.1177/0269216313493467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence End of life care for adults. London: NICE; 2011. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/QS13. [Accessed November 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jennings AL, Davies AN, Higgins, et al. A systematic review of use of opioids in the management of dyspnoea. Thorax. 2002:939–44. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.11.939. JPT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorman S, Jolley C, Abernethy A, et al. Researching breathlessness in palliative care: consensus statement of the National Cancer Research Institute Palliative Care Breathlessness Subgroup. Palliat Med. 2009;23:213–27. doi: 10.1177/0269216309102520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen S, Raut S, Woollard J, Vassallo M. Low dose diamorphine reduces breathlessness without causing a fall in oxygen saturation in elderly patients with end-stage idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Palliat Med. 2005;19:128–30. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm998oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartzstein RM, Lahive K, Pope A, et al. Cold facial stimulation reduces breathlessness induced in normal subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:58–61. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Non-pharmacological interventions for breathlessness in advanced stages of malignant and non-malignant diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD005623. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005623.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heslop K. Cognitive behavioural therapy in cystic fibrosis. J Royal Soc Med. 2006;99(Suppl 46):27–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abernethy AP, McDonald CF, Firth PA, et al. Effects of palliative oxygen versus room air in relief of breathlessness in patients with refractory dyspnoea: a double-blinded randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:784–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61115-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morice AH, Menon MS, Mulrennan SA, et al. Opiate therapy for chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:312–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-892OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wee B, Browning J, Adams A, et al. Management of chronic cough in patients receiving palliative care: review of evidence and recommendations by a task group of the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland. Palliat Med. 2012;26:780–7. doi: 10.1177/0269216311423793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sleeman KE, Collis E. Caring for a dying patient in hospital. BMJ. 2013;346:33–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]