Editor – We read with interest the article by Mujakperuo et al on the use of interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) testing for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis (TB) (Clin Med August 2013 pp 362–6). We wish to highlight four important points surrounding the management of TB outbreaks in the immunocompromised setting and propose an original screening algorithm:

Immunocompromised patients undergoing anticancer chemotherapy are known to have a higher incidence of TB1 and a higher inpatient mortality related to TB when compared to immunocompetent patients.2

Diagnosing active TB in this cohort is difficult as the clinical presentation is often not typical and non-HIV-immunocompromised patients have a higher occurrence of extra-pulmonary TB.2

Screening for latent TB poses a challenge given the immunological basis of both the Mantoux tuberculin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assays (IGRA). NICE guidelines recommend offering immunocompromised patients an IGRA test alone or concurrent with a TST.3 This recommendation is consistent with the recently updated Canadian Thoracic Society guideline.4

There is insufficient evidence as to whom we should consider a ‘close or casual contact’ and what constitutes a ‘cumulative exposure’ in this context.3,4

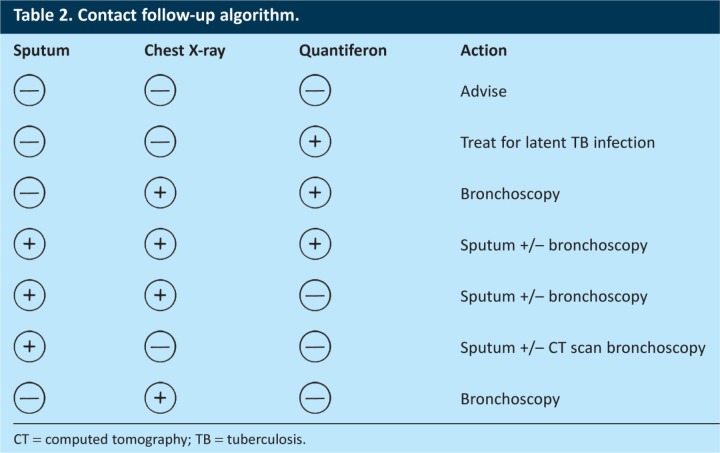

A patient attending the hemato-oncology day ward at our institution was diagnosed with sputum smear-positive pan-sensitive TB. A multi-disciplinary expert committee devised an original algorithm for contact screening purposes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Contact follow-up algorithm.

Persons with a cumulative exposure of more than 4 hrs with the index case were traced. 17 contacts identified underwent screening with sputum sampling, IGRA and chest radiograph (CXR). Round one revealed 2 contacts with positive IGRAs. Both commenced TB prophylaxis. One patient with an abnormal CXR was referred for computed tomography (CT) imaging. Round two of screening, 8 weeks later, identified one asymptomatic patient with an ‘indeterminate’ IGRA who commenced prophylaxis. Follow up of all contacts continued for 1 year.

We need to exercise extreme vigilance and consider TB as an early differential in this vulnerable cohort. A prompt multi-disciplinary approach minimised the risk for patients in this case. Establishing universal guidelines with standard definitions for ‘close contact’ and ‘cumulative exposure’ in this context would alleviate delays in initiating contact investigations in the future instances.

References

- 1.De La Rosa GR, Jacobson KL, Rolston KV, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis at a comprehensive cancer centre: active disease in patients with underlying malignancy during 1990–2000. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:749–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silva DR, Menegotto DM, Schulz LF, et al. Clinical characteristics and evolution of non-HIV-infected immunocompromised patients with an in- hospital diagnosis of tuberculosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2010;36:475–84. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132010000400013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Tuberculosis clinical diagnosis and management of tuberculosis, and measures for its prevention and control. London: NICE; 2011. www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13422/53642/53642.pdf [Accessed 27 September 2013]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Thoracic Society and Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian tuberculosis standards 7th edition. Ottawa: Canadian Thoracic Society and Public Health Agency of Canada; 2013. www.respiratoryguidelines.ca/tb-standards-2013 [Accessed 27 September 2013]. [Google Scholar]